Throughout 1940 and much of 1941, Tronstad continued his teaching and research in Trondheim — and his work for the Norwegian resistance. Behind blackout curtains, he met with community leaders active in pushing back against German oppression in the city. Tronstad was also close to several bands of university students. Some published illegal newspapers. Others operated at a higher level in connection with the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), sending coded wireless radio transmissions to London to report on German troop movements and naval activity. Tronstad — code-named “The Mailman” — gave them any technical help they needed and provided intelligence of his own from his many industrial connections. He also supplied crucial information about Vemork’s supply of heavy water.

On the morning of September 9, 1941, a student visited Tronstad for advice on hiding the wireless radio that he had been using to send messages to the SIS. The Gestapo arrested the student that same afternoon. A week later, they seized the courier Tronstad had tasked to go to London by ship. On the wharf’s edge, the courier swallowed the cigarette paper with the information he was carrying, but it was a close call. Tronstad knew the Gestapo would likely come for him next.

On September 22, Tronstad went to Bassa and told her they must flee. That evening, the family boarded a 7:15 train to Oslo with their hastily packed suitcases. In the sleeping compartment, Tronstad wrote the first entry in the small black diary he would keep through the war: “Family, house and worldly goods have to be set aside for Norway’s sake.”

The next morning, they arrived in Oslo and took another train to a neighborhood a short distance outside the city. From the station, they climbed up the hill to Bassa’s childhood home. He made sure Bassa knew to tell anybody who asked that he was headed west toward Telemark, and they hugged. Then he kneeled beside his children. “Take care of your little brother,” he told nine-year-old Sidsel. Then he turned to four-year-old Leif. “You must be good for your mother while I’m gone.” He promised to bring back a little gift for each of them. “Be kind to each other,” Tronstad said before hurrying away, so overcome with emotion that he forgot to hug them.

In Oslo, he collected fake identity papers, and the next morning he borrowed a bicycle and rode twenty miles north, where the Milorg resistance network picked him up and ferried him out of the country. Weeks later in Stockholm, he boarded a transport plane that took him across the North Sea. On October 21, he arrived at King’s Cross Station in London. SIS arranged a room for him at St. Ermin’s Hotel in the heart of Westminster, a stone’s throw from the spy agency’s headquarters.

Tronstad knew London well from his student days, but now he found it a war zone. Soldiers crowded the streets, and a floating armada of gray barrage balloons hung in the sky to interfere with German bombers. The streets were strewn with the rubble of bombed-out buildings. Many thousands of people had been killed in the Blitz, and countless more had been wounded and left homeless.

Within days of his arrival, he sat down with Eric Welsh, the SIS spy responsible for Norway. Tronstad revealed what he knew about Nazi interest in Vemork, particularly the huge spike in heavy-water production. He discovered the British were also pursuing an atomic bomb — and they were deeply concerned about the work of their Nazi rivals.

In September 1939, when Hitler invaded Poland, he boasted to the world that he would soon “employ a weapon against which there would be no defense.” This prompted Sir Henry Tizard, head of the Air Ministry’s research department, who was already fearful of Nazi advances in atomic science, to look even more urgently into the production of a British bomb.

Two physicists, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, both Jewish refugees from Germany, put the British firmly on their path. On March 19, 1940, their report, “On the Construction of a Super Bomb,” landed on Tizard’s desk. They detailed that one pound of pure uranium-235 — divided into two (or more) parts, which were then smashed together at a high velocity — would initiate an explosion that would “destroy life in a wide area … probably the center of a big city … at a temperature comparable to the interior of the sun.” Peierls and Frisch suggested that German scientists might soon “be in possession of this weapon.” Britain could only counter this threat, they concluded, by obtaining a bomb as well.

The following month, the British government began exploratory research with some of its best scientists. In July 1941, the group delivered a road map for an atomic bomb program. On receiving it, Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote to his War Cabinet: “Although personally I am quite content with the existing explosives, I feel we must not stand in the path of improvement.” The Cabinet agreed, promising “no time, labor, material or money should be spared in pushing forward the development of this weapon.” Thus, the “Directorate of Tube Alloys” —the code name for the British atomic bomb program — was formed.

Throughout this period, fears over the German bomb continued. From far and wide came whispers, rumors, threats, and fact — which, mixed together, made for the typically confusing brew that governments called “intelligence.” Two drunken German pilots were overhead on a tram speaking about “new bombs” that were “very dangerous” and had the power of an earthquake. One émigré German physicist warned that there was pressure from high within the Nazi government to build a bomb, and the Allies “must hurry.” A military adviser in Stockholm reported, “A tale has again reached me that the Germans are well under way with the manufacture of an uranium bomb of enormous power, which will blast everything, and through the power of one bomb a whole town can be leveled.” SIS heard of a mysterious September 1941 meeting where Werner Heisenberg admitted to Niels Bohr, who was living in Nazi-occupied Denmark, that a bomb could be made, “and we’re working on it.”

The best intelligence the British received came through German activity at Vemork. As early as April 1940, a French spy with close ties to Norsk Hydro had alerted his British allies to Nazi efforts in uranium research using heavy water from the plant. Leif Tronstad provided another gold mine of information. What the Norwegian professor revealed about the increased levels of production left officials at the Directorate of Tube Alloys and high in the British government deeply on edge. Whatever position Tronstad decided to take in his fight against the Nazis, whether as a scientist or as an official in the exiled Norwegian government based in London, the British wanted him to continue to gather intelligence about Vemork and the German atomic program. Tronstad agreed.

On December 2, 1941, Haukelid was woken up by dogs barking. There was a chill in the air, and frost clouded the windows overlooking the huge wooded estate of Stodham Park, fifty miles southwest of London. He had escaped to Britain in November because of the same intense Gestapo manhunts that had driven Tronstad from Norway. Now he was part of a group of roughly two dozen Norwegians who had volunteered to attend special commando training to fight for their homeland.

Quickly, Haukelid dressed in his new British uniform, its starched collar surpassed in stiffness only by his standard-issue boots. Outside, he stood with his fellow soldiers. They came from every walk of life: rich, poor, and in between; from city, town, and backwoods country. A few had never handled a gun before; others were marksmen. Some were boys, barely eighteen. Most were in their twenties, and a few were old men — all of thirty, like Haukelid. Before the war, they had been students, fishermen, police officers, bankers, factory workers, and lost types looking for their place in this world — again, just like Haukelid. Together they learned to kill, to sabotage, and to survive, any way and any how. Their grizzled Irish sergeant major, who went by the nickname “Tom Mix,” taught them no rules but one: “Never give your enemy half a chance.”

The squad of new recruits started their day at 6 A.M. with what Mix liked to call “Hardening of the Feet”: a fast march on the estate. A short breakfast was followed by weapons instruction. “This is your friend,” Mix said, twirling his pistol around his finger. “The only friend you can rely on.” Then he took them out to a grove in the woods and taught them how to stand — knees bent, two hands on the grip of the pistol — and how to fire: two shots quickly in a row to make sure the enemy was down. If circumstances allowed, Mix said grimly, “aim low. A bullet in the stomach, and your German will squirm for twelve hours before dying.” Haukelid had grown up hunting, but this was very different.

After two hours of shooting, they spent another hour in a gym. They pummeled punching bags, wrestled, and learned how to take down and disarm an enemy with their bare hands. A break for coffee, then instruction in how to send and receive messages in Morse code. This was followed by lunch, then a two-hour class in demolition. “Never smoke while working with explosives,” Mix said, a lit cigarette perched between his lips, again offering the point that rules existed to be broken. They blew up logs and sent rocks skyward. Ears ringing, they moved on to orienteering class, navigating the estate with maps and compasses, then field craft — stalking targets and scouting routes through the woods. From 5 to 8 P.M., they were free to relax and eat before the night exercises began. Those consisted of more weapons, more explosives, more unarmed combat — now executed in the pitch-dark.

Through day after day of this schedule, his boots and collar softening with each hour, Haukelid turned into a fighter. Though fit at the start, he became fitter still. On occasion, he would be invited into a room with an officer or a psychiatrist and asked if the training was too much, too hard, if he might want to quit. This kind of work wasn’t for everybody, they said.

It was for him.

Firing two shots in rapid succession became a reflex, and his aim grew lethally accurate to the range’s paper targets. He learned how to time throwing a hand grenade (“One can go from here to London before it explodes,” Mix said). He gained expertise in hand-to-hand combat and in the use of a knife. He grew skilled at demolitions, able to light a ten-second fuse without his hands shaking.

After three weeks of this instruction, Haukelid graduated from what his Stodham Park instructors told him was only preliminary training. On December 20, 1941, he boarded a train to Scotland for further lessons.

At Meoble, an old hunting lodge on the windswept coast of the western Highlands, the training began with scrambles through thick brush, crossing ice-cold rivers, and rappelling down steep ravines. Using both British and foreign weapons, he practiced instinctive shooting (shooting without the use of sights) and close-quarter firing. In demolitions, he graduated from blowing up logs to destroying railroad cars. He crafted bombs of all sizes and was amazed at what a small charge placed in the perfect spot at the perfect time could do: It could stop an army, obliterate a weapons plant.

He was taught how to break open safes, how to use poison, how to knock out a guard with chloroform. He practiced how to kill silently with a knife. He learned how to follow a route to a target by memory alone, how to camouflage himself in the field, how to crawl through a marsh and reach his assailant undetected, how to take him down without a sound — without even a weapon. “This is war, not sport,” his instructors reminded him. “So forget the Queensbury rules; forget the term ‘foul methods’ … these methods help you to kill quickly.” A sharp blow with the side of his hand could paralyze, break bones, or kill.

Even the occasional night off was instructive. For New Year’s Eve, Haukelid and the others in his squad were taken to a pub to celebrate. At first, it seemed like a good time, but they were enlightened later that they were watched all evening to see who drank too much, who made a fool of himself, or, worst of all, who spoke of what he should not, as one had always to be on one’s guard. It was a merciless regime, and as before, Haukelid was asked regularly if he wanted to back out. He refused.

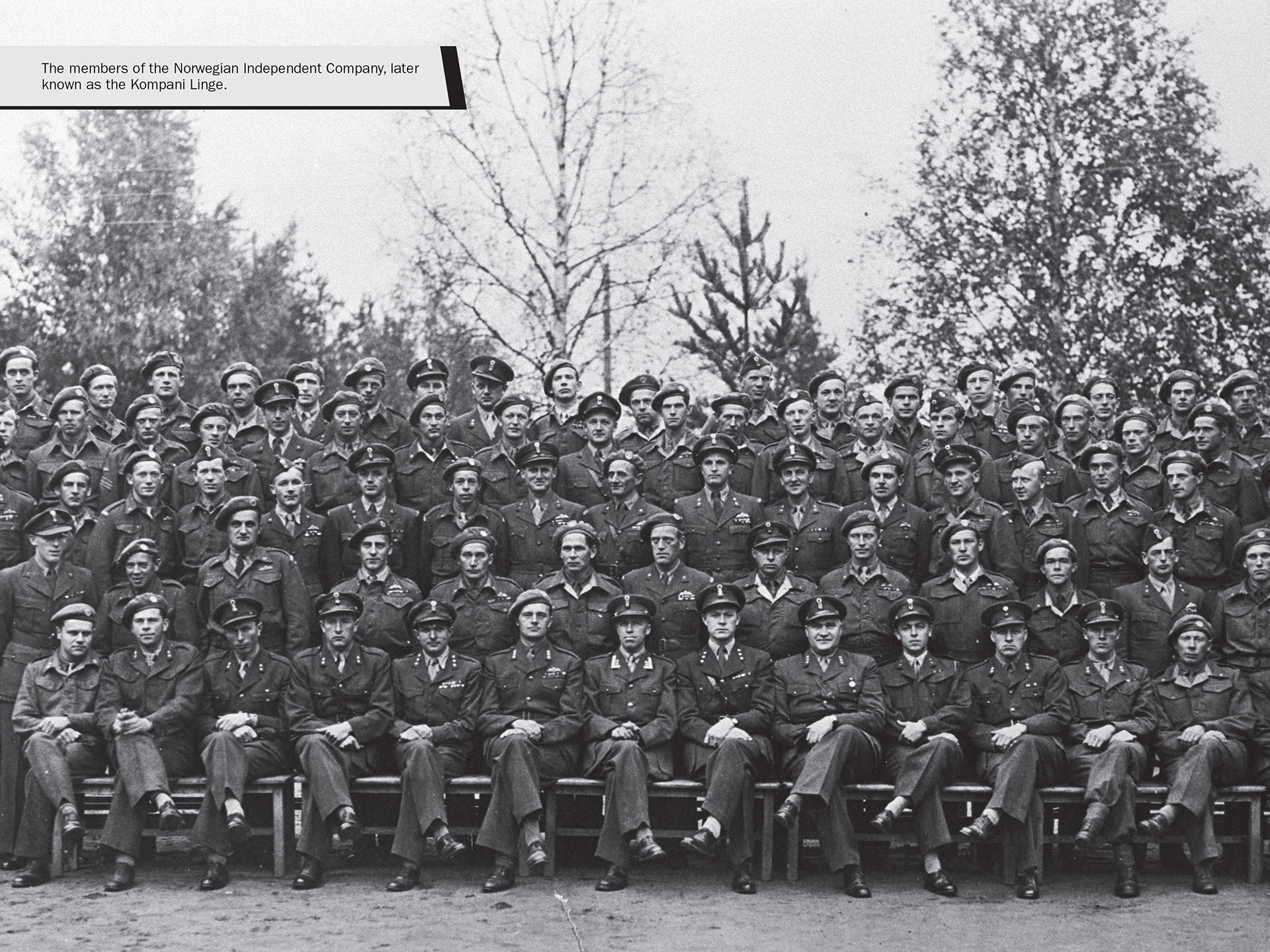

On January 14, 1942, Haukelid arrived at Special Training School 26, in the Scottish Highlands near Aviemore, the home of Norwegian Independent Company No. 1. Roughly 150 Norwegians lived in three hunting lodges amidst the cragged granite mountain peaks, steep valleys, and long stretches of moors. The place reminded Haukelid almost too much of his homeland, but that meant it was the ideal terrain to prepare for missions.

The Norwegian company was part of an expansive British organization called the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Founded by Churchill in 1940, its directive was to “set Europe ablaze” with commando missions against the Nazis. Its masterminds, who started the organization from three rooms at St. Ermin’s Hotel, called themselves the “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare.”

Haukelid was happy to be surrounded by Norwegians like him, who had risked everything to come to England to learn to fight. For two weeks, he trained with his new company and roamed the snowbound countryside. Then, on January 31, several visitors came up from London by night train. The company showed off their shooting and raid techniques, and then hosted a dinner at one of the lodges at STS 26. Oscar Torp, the Norwegian Defense Minister in exile, and Major General Colin Gubbins, second-in-command of the SOE, were the guests of honor. Torp gave a rousing speech, promising a new era of cooperation between the exiled Norwegian government and the British. Their aim in Norway was twofold: the long-term goal of building up Milorg, the underground military resistance in Norway, in anticipation of a future Allied invasion; and the short-term goal of performing sabotage operations and assisting in raids to weaken the Germans. The Independent Company would be at the forefront of any attack. When he finished, the men cheered and pounded on their tables.

Then Torp and Gubbins introduced the two officers who would command them. The first was Lieutenant Colonel John Wilson, the new chief of the SOE Norwegian section. He told them that he had “Viking blood” in his veins but that over the generations it had thinned like his graying crown of hair. At fifty-three years of age, he had a short but upright bearing, a quiet, stern voice, and a determined manner. Wilson had helped design and run the SOE’s training schools. Next to Wilson, dressed in uniform and cap, stood Leif Tronstad, whom Haukelid had briefly met on the fateful morning of the German invasion. Coordinating closely with Wilson, Captain Tronstad would oversee the company’s training, planning, and execution of operations, and direct the Norwegian soldiers in their fight for their country. Haukelid pleaded for that chance to come soon, but it was not yet his turn. Others would first have theirs.