“Number one, go!” the dispatcher yelled through the cold wind whipping into the plane. It was 11:36 P.M., October 18, 1942, and a full moon hung in the sky, perfect for a parachute drop. With a surge of excitement and fear, Poulsson edged himself out of the open hatch on the floor of the Halifax’s belly. He tipped forward, then suddenly he was falling, falling fast.

Below him spread out the Vidda in the clear moonlight: its snow-peaked mountains, isolated hills, lakes, rivers, and narrow ravines. It was a place both beautiful and terrible, and Poulsson knew it must be respected. At 3,000 feet above sea level, it was exposed to unpredictable weather and high winds that could hurl a man off his feet. In the winter, a skier could be sunning himself on a rock one moment only to find a storm sweeping through the next, bringing blinding slivers of ice and snow and temperatures below minus 30 degrees Celsius. Norwegian legends said it could grow cold enough, quickly enough, to freeze flames in a fire. Simple fact said it could kill the unprepared in two hours.

The Germans had steered around the Vidda when they attacked Norway, and even now they dared venture only far enough into it that they could get out by sunset. There were no roads and no permanent habitations in the 3,500-square-mile expanse of land — larger than the state of Delaware. Only skilled skiers and hikers could reach its scattering of hunting cabins. In the valleys, one could find birch trees, but many areas were simply frozen barren — lifeless hillsides of broken scree, one mile the same as the next.

As his parachute snapped behind him and he prepared to land, Poulsson found himself unable to identify the rockless, flat Løkkjes marshes, twenty miles west of Vemork, where they had expected to be dropped. Instead, there were only snow-patched hillsides of boulder and rocks — ideal for snapping one’s neck.

He landed hard, but luckily without injury, and called out to the other members of the Grouse team, who had followed him out of the plane. Kjelstrup and Haugland were in good shape, but Helberg walked gingerly, having come down against the edge of a boulder. On examination, the back of his thigh was swelling, but there was no fracture. He did not complain.

For the next four hours, they searched the hillsides for their eight containers of gear, most importantly their stove, tent, and sleeping bags. If a storm hit, they would be in trouble without those essential supplies. With the aid of moonlight, they found everything, but it was too late to do anything more than take shelter from the wind beside a boulder and settle in for the night. The four huddled together. It was cold but bearable. They each wore long underwear and two pairs of socks, all made of wool, then gabardine trousers, buttoned shirts, and thick sweaters. Over these went parkas and windproof pants, wool caps and two pairs of gloves. If the weather got nasty, they could always pull their balaclavas over their faces and don their goggles.

Poulsson dug into his pouch of tobacco and prepared his pipe, a ritual that somehow eased the nerves of the others. He lit the pipe, puffed a couple of times, and then revealed to Helberg and Kjelstrup, “There’s a new order of the day.” No longer were they there to build up a network of underground resistance cells, he said; instead, they were the advance team for a sabotage operation. After learning the details of the Royal Engineers plan, Helberg thought it was a suicide mission for the British troops: How would they escape Norway? All four Norwegian commandos, however, were happy they would be in on a bigger job. As Haugland thought, “You don’t jump out of a plane over your occupied country to contribute a little something.”

Divided into a pair of tents, using their parachutes as groundsheets, the four slept for a few hours in their sleeping bags. They woke to a clear blue sky, the surrounding rugged hills cast in sharp relief. They were home now, far from soggy Scotland, and the air was crisp and dry. Examining the terrain, Poulsson determined that they had landed on the edge of the Songa Valley, more than ten miles west of their intended drop point.

The men spent two backbreaking days dragging together the eight containers of supplies scattered about the area. On inspection, they found some serious problems. First, there was no paraffin fuel for the stoves in any of the containers. Fuel would have allowed them to hike a straight course over the barren mountains to the Skoland marshes, where they would meet the Engineers. But crossing the Vidda was too great a risk without some source of heat, so they would have to travel through the valley, where there would be cabins for shelter and birch trees for firewood. That added a lot of distance and at least several days to their journey.

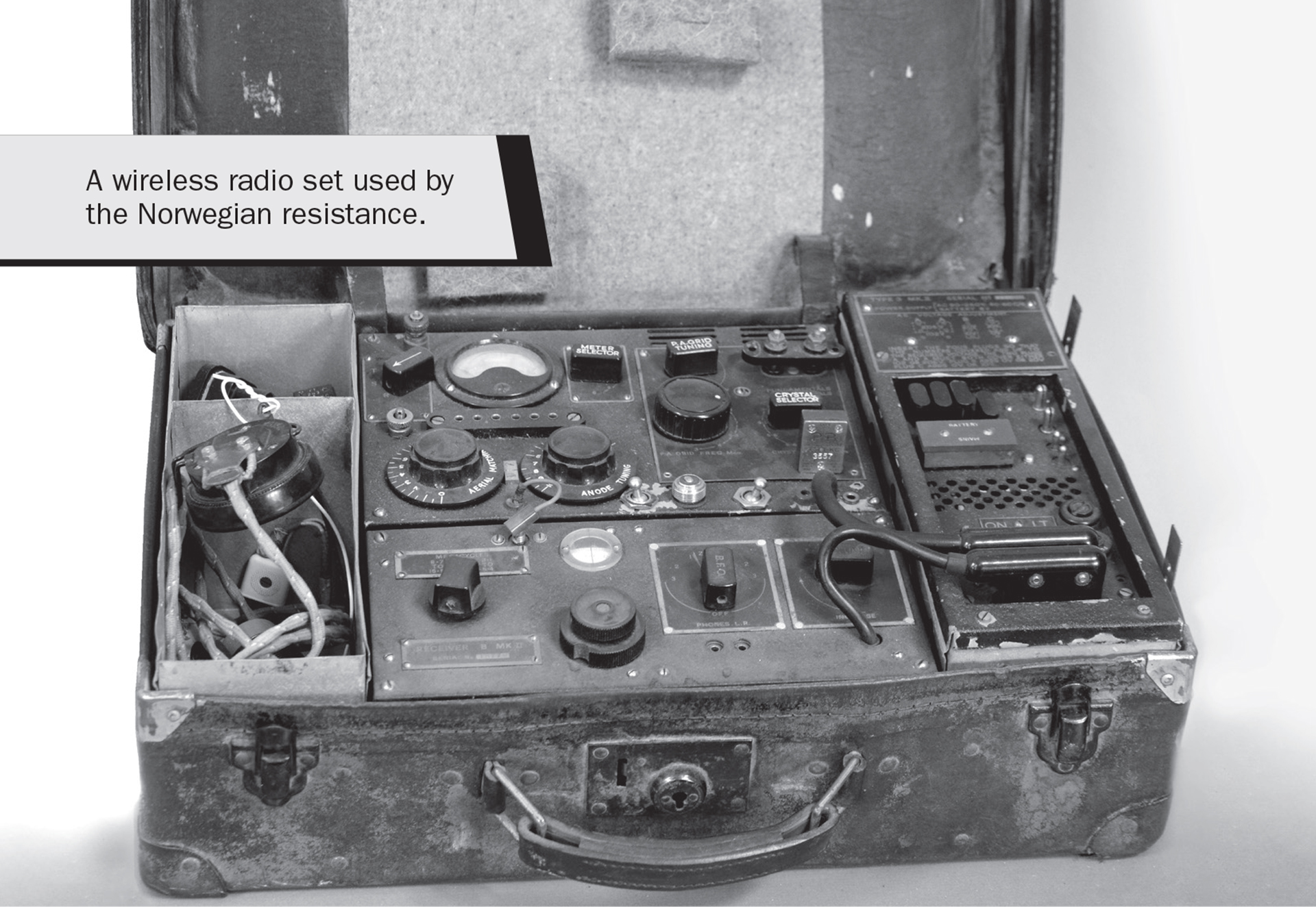

Second, their British packers bungled the radio equipment. They had failed to include bamboo poles, which were used to rig up an antenna, and they had replaced the standard-issue Ford car batteries for the wireless set and their homing beacon with ones that weighed twice as much. Worse, these batteries were stamped MADE IN ENGLAND. The British connection would put anyone involved in recharging the batteries in serious danger if they were caught.

They tried tying together ski poles with parachute cord to form an antenna, but they did not succeed in reaching London by wireless. Now they faced a forty-five-mile trek with heavy packs to the marshes in time to meet the British sappers.

Lieutenant Colonel Mark Henniker was put in charge of the preparation and planning of the Vemork mission, which had been code-named “Operation Freshman.” Under his watchful eye, two field companies of the Royal Engineers got a week’s training: marching, practicing shooting, sleeping on straw mats, and suffering lectures on how to keep their feet healthy (two pairs of dry socks). Then they were shipped off to northern Wales, where they were sent on long treks through the Snowdon Mountains, using a compass and map, eating hard rations, marching through bogland and up and down steep slopes. They slept huddled closely together, a mound of men sharing not enough blankets.

Combined Operations decided to bring the sappers to their target by plane-towed gliders instead of dropping them by parachute. It was a risky choice: After the planes released the gliders, 10,000 feet in the air, the glider pilots would have to land their crafts at night, in foreign territory prone to shifting weather and uncertain terrain. This would be the first time the British tried gliders in an operation. But using parachutes would require that the sappers be dropped near the plant, which increased the risk of their being noticed. Worse, the sappers might be injured on landing in the rugged terrain, and they might be too spread out to find each another in quick order. Gliders would land silently, and all the men would be together, with all the equipment required for the operation at hand.

The plan took shape. The Grouse team would use lights to signal the two gliders to land in the Skoland marshes. They would also employ the new Eureka/Rebecca system, an untested technology whose radio signals provided a homing beacon to planes. They would then guide the sappers to the plant. At Vemork, the British troops would cross over the suspension bridge, neutralize the small number of guards, and place almost 300 pounds of explosives to blow up the power station’s generators and the hydrogen plant. Once away from the plant, they were to separate into groups of two or three men and change into civilian clothes. Then they were to hike the 200 miles to Sweden.

On November 2, Henniker’s men were brought to STS 17, the SOE’s industrial-sabotage school in Brickendonbury Hall, an old manor house. Leif Tronstad met them there. He gave them blueprints of the buildings as well as photographs and drawings of the equipment to be targeted, which Brun had secreted out of Norway. (Given the impending operation, the Vemork plant manager had been smuggled across the Swedish border and brought to England.) Thanks to information from Skinnarland and Brun, the sappers came to know virtually everything about Vemork, from the type of locks on the doors to the number of steps required to reach the heavy-water high-concentration plant on the basement floor. They even practiced placing explosives on a wooden mock-up of the heavy-water concentration cells.

There was just one problem. It had been more than two weeks since Grouse had left, and Tronstad had heard nothing from them. Without the four young Norwegians on the ground, without regular radio contact, Operation Freshman could not take place.

Like all the members of Operation Grouse, radio operator Knut Haugland was cold, hungry, exhausted, and wet — and worse, he was weighed down with seventy pounds of equipment. The team had buried a depot of supplies that they would not need until after the sabotage in the snow, then left their drop spot on October 21 for the forty-five-mile trek to the Skoland marshes. In ideal conditions, they could have crossed this distance in a couple of days, skiing straight across the frozen surface of the many rivers and small lakes that marked the Vidda. But they had 560 pounds of supplies to carry — 140 pounds for each of them — impossible to haul unless they split it into two journeys. Thus they would ski a few miles with seventy-pound loads, empty their backpacks, and take a short break to eat. Poulsson had rationed them each a quarter slab of pemmican (a pressed mix of powdered dried game, melted fat, and dried fruit — the most treasured part of their ration), four hard crackers, a pat of butter, a slice of cheese, a piece of chocolate, and a handful of oats and flour for the day. Their break over, they returned to their starting point and retrieved another seventy pounds of their equipment and food, to repeat the journey over again. Worse, in late October, the ice on the lakes and rivers was not yet completely frozen. In the few places they tried, the surface water on the ice left their boots and socks drenched.

Given all of this, by the end of the third day, they had advanced only eight miles from their drop site. Before dark, they came across an abandoned farmhouse beside Songa Lake. They broke in and found some frozen meat, which they hacked apart with an ax. They built a fire, melted snow in a pot, then softened the meat in the boiling water. For the first time in almost a week, they feasted until their bellies were full. Better still, they also found an old sledge.

Over the next six days, the team made slow, steady progress east, their supplies now split between their backpacks and their newfound sledge. No longer did they need to make the double journey. Still, the snow was heavy to wade through, the rations strict, the terrain rough, and the stretches of water a risk to cross. Poulsson once fell through the ice of a half-frozen lake, and Kjelstrup, his body stretched flat on thin ice, had to pull him free with a pole. At night, they broke into cabins for shelter, but none held the same booty as the first farmhouse. They ate their pemmican, sometimes cold, sometimes mixed with oats or flour in a hot gruel, but they were always left wanting more. As one day followed the next, the four grew thin and their beards scraggly, their cheeks and lips blistered from the constant wind, cold, and toil. They were almost always wet, as their clothes never dried completely at night. Their skis grew waterlogged. Their Canadian boots were fraying. Had it not been for all their hard training in Scotland, they would already have given up.

As they traveled, Haugland took enough fishing rods from cabins to build a mast for the antenna. One night, he fired up his wireless set, only to have it short-circuit moments later. He cursed his bad luck. Haugland had always wanted to be a radio operator, an ambition fueled by a naval adventure novel he had read as a teenager, which featured a radioman saving his whole crew. Operating a radio set in Morse code had been like learning to play the piano. At first he was all thumbs, slow and stuttery, but after practice, practice, practice, he found that he was a master, tapping out dots and dashes without thinking. He joined Kompani Linge soon after arriving in Britain and attended STS 52, the specialized school for wireless operators, where his teachers said he should be instructing them.

Now, thirteen days into his first operation, Haugland still had not managed to get his radio to function. Determined not to fail again, he set about fixing the wireless set. When ready, he turned it on, hoping that the shortwave signal from his mast would reach the operators at Home Station in England.

Straightaway, he got reception, and then, an instant later, nothing. The battery, all thirty pounds of it, “Made in England,” was dead.

The mood in the cabin felt grim. In sixteen days, the moon would be in position for the operation against Vemork. Their team had to be in place to recon the landing site, provide weather reports and intelligence on Vemork, and receive the British sappers. They still had many miles to go, and they had no working radio.

They buried the battery, and Helberg went ahead of the others to Lake Møs dam, seeking help from Torstein Skinnarland, Einar’s brother, who served as an assistant keeper of the dam. Even though Grouse had been ordered not to make contact with Skinnarland or any locals in order to maintain the secrecy of their mission, Poulsson felt they had no choice. No radio, no sabotage of Vemork. With new snowfall and a drop in temperature, conditions on the ground improved, and the other three made quick progress east over the next two days. Helberg met them at a river crossing on his return from the dam. Torstein would provide a new battery, he said, but it would take some time. He also suggested an old cabin they could hide in.

In the early hours of November 5, the Grouse team arrived at a cabin beside Sand Lake, three miles east of the Skoland marshes. Once inside, the four collapsed. Dirty, unshaven, their faces chafed from the cold, they looked like mountain men, and half-starved ones at that. They slept that night like the dead.

The next day, Haugland started constructing his aerial antenna again. He lashed together two thin towers made from fishing poles, set them fifteen feet apart, and strung copper wire between them. While he worked, Helberg departed for the dam to retrieve the battery, and Poulsson and Kjelstrup skied to the marsh to inspect the landing site.

In the woods by the Lake Møs dam, Einar Skinnarland waited for Claus Helberg. Throughout the six months Skinnarland had spent living a double life — working at Norsk Hydro while spying for the British — his fear of discovery had been constant. He had several informants at Vemork, and one had been interrogated recently by Rjukan’s police chief. Nothing came of it, but a loose word, a single mistake, by any of a number of people, including Skinnarland himself, and he would be lost. Despite these risks, he was often given less information than he needed from his handlers in London, whether because of communication breakdowns or because of need-to-know secrecy.

News that Grouse had already arrived in Norway, no less at his brother’s doorstep, was testament to this problem. Such surprises invited disaster. Still, Skinnarland came instead of Torstein to pass Helberg the freshly charged battery. Einar offered his compatriots any help they might need in the days ahead, whether supplies or intelligence. He quickly became part of the team.

After dark on November 9, Haugland finally thought he had everything set to restart the radio. He had already coded his message, a jumble of letters on the notepad in front of him. It needed to be short and quick because the Germans operated D/F (direction finding) radio stations that tuned in on broadcasts from Norway. If Haugland transmitted for too long and two German stations were close enough, they could zero in on Grouse’s position. As a radio operator, Haugland knew that brevity and speed were arts that saved lives — his own among them.

The new battery feeding in a steady current, Haugland powered up the wireless set. The three other Grouse team members watching closely, his hand trembling from the cold and excitement, he sent out his identity call sign. He immediately received an answer in return. They had contact. The four cheered. Haugland delivered his first message: “Happy landing in spite of stones everywhere. Sorry to keep you waiting. Snowstorm and fog forced us to go down valleys. Four feet of snow impossible with heavy equipment to cross mountains. Had to hurry on for reaching target area in time. Further information. Next message.”

Grouse was in place for its mission, and ready to guide the paratroopers to their target.