On November 15, Tronstad sat down with Wilson, Henniker, and several others to go over the plan for Operation Freshman one last time. Despite his misgivings about destroying a plant that he had helped to build, the more Tube Alloys told him about the Germans’ atomic research efforts, of “super bombs” that would equal “1,000 tons of TNT,” the more Tronstad knew they needed to be stopped.

He delivered the latest messages from Grouse: They suggested the sappers bring snowshoes, but said that even under bad conditions the march to Vemork should not take more than five hours. With the help of Einar Skinnarland, the team would cut the telephone line between the Lake Møs dam and Rjukan on the night of the operation. There were two guards at the door to the hydrogen plant, and the sappers would have no trouble overpowering them. If more forces came from Rjukan, the suspension bridge could easily be held.

Henniker said that he would only need two guides from Grouse on the approach to the plant. Their role would end when the Royal Engineers went across the suspension bridge. The other Grouse men were to operate the wireless and destroy the radio homing beacon, a technology the British did not want to fall into German hands.

Overall, the mood of the meeting was very positive. Toward its close, Tronstad presented diagrams of the plant’s layout. He said he understood the mission’s importance, but he worried that destroying all the power station’s generators would hurt the livelihoods of most of the Norwegians in Rjukan and eliminate fertilizer supplies his country desperately needed. Instead, he sketched out a plan to save two of the twelve generators, which would have the same effect on heavy-water production but keep Vemork alive as a hydrogen plant. Henniker offered to raise the point with his superiors, but time was running short for making changes to the plan.

Tronstad was sure he had been given a polite brush-off, but he prepared a report that finally won him the change. In it, he concluded, “Good policy for destruction of plants in Norway is namely to do just as much damage as strictly necessary — to prevent the Germans from winning the war — and nothing more.”

In a dark, windowless corner of the cabin on Sand Lake, Poulsson tended a huge pot of boiling sheep’s-head stew. Earlier that day, Haugland and Helberg had come across a sheep that had strayed from its flock and got caught in some rocks. Desperate for food, they killed it. Poulsson fancied himself a bit of a cook, so he had added some canned peas and whatever else he could find in their stores to improve the stew’s flavor. Not that the others would complain, he knew, as all of them were starving. The smell wafting from the pot already made their mouths water. The boys had even set a cloth over the table.

Outside, the wind howled, hurling snowflakes into the cabin through the many breaks in the walls. The single, lit candle flickered so much they could barely see one another. On his way to the table with the huge pot in hand, Poulsson slipped on a reindeer rug. An instant later, the stew spilled across the floor, sheep’s head and all. Everyone gazed at it, then at their cook. Without a word, the four got down on their knees and scooped whatever they could into their mouths. In the end, there was nothing but picked-over bones and jokes from Kjelstrup about having “hair in my soup.”

The British gliders needed the light of the full moon to land. In the three days leading up to November 18, the start of the full moon phase, Grouse stayed busy. They scouted the route down to the target. From a hidden position on the opposite side of Vemork, they watched the guards on the bridge. Helberg continued to venture back and forth from Lake Møs for supplies and batteries. Haugland was the busiest, constantly coding and decoding messages to and from London. Some of his scheduled broadcasts took place after midnight, and he emerged from the shell of his sleeping bag only as far as he needed to tap out his Morse. Mostly he sent word about the weather, which had been very unpredictable. One day it was clear. The next, there were high clouds, and the next the clouds lay low across the valley like a blanket. Some nights it snowed lightly; others were merely freezing cold. The winds came in squalls from shifting directions.

On the morning of November 19, Haugland transmitted that the weather over the landing zone was clear for a second consecutive day. There were no clouds and the northwest winds were light. If the weather held, everything was in place for the British arrival.

That afternoon, twenty-eight Royal Engineers ate sandwiches and smoked cigarettes on the barren seaside moor that made up Skitten Airfield. Some bantered about the upcoming mission, but most handled their nerves in silence. There would be a final briefing, but they already knew what they needed to know: They were heading to Norway to blow up a power station and hydrogen plant. The sappers still had no idea what purpose the “very expensive liquid” produced at Vemork served. However, given the blanket of security everywhere they traveled, and the orders to strip off their uniforms’ badges and insignia, they knew it must be important.

After they finished their tea, the sappers kitted up. They wore steel helmets and British Army uniforms with blue rollneck sweaters underneath. Each of them had a Sten gun, a backpack filled with ten days of rations, an escape kit, explosives, and other equipment. Some of them carried silk maps with the target circled in blue and a false escape route. After the operation, these would be dropped to throw off their pursuers.

Under a slight drizzle, the sappers strode out onto the runway, where two black Horsa gliders waited behind Halifax airplanes. Most of the sappers were in their early twenties, and one observer on the ground noted they looked like schoolboys. While the Halifax crews went through their checks, the sappers boarded the gliders, taking their positions in the fuselage and strapping on their safety harnesses. The floor beneath their boots was corrugated metal, its long channels designed to prevent slipping on the vomit that was a usual result of these glider flights.

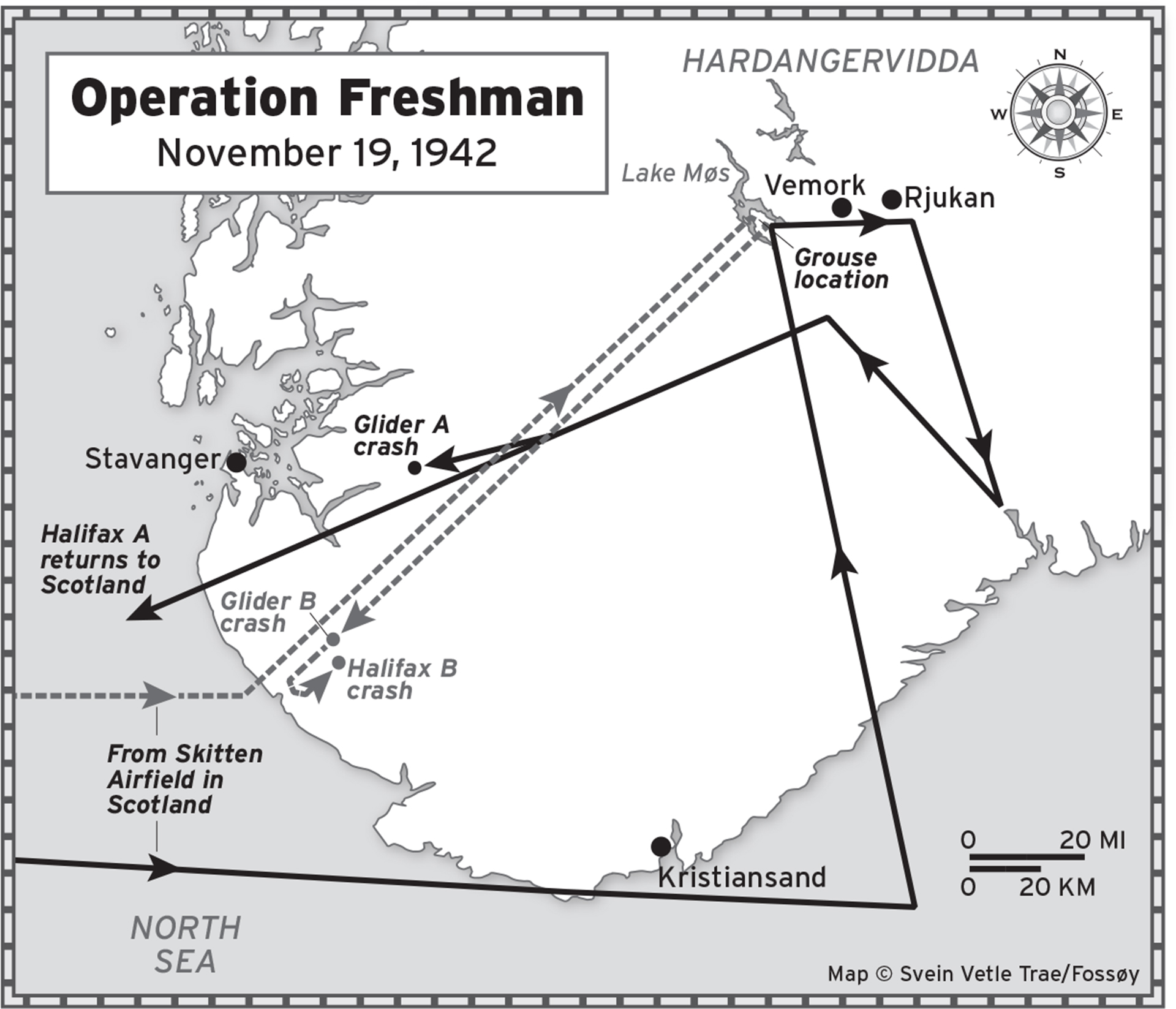

After a slight delay, the Halifaxes powered up. At 6:45 P.M., with a wave from the crews, Halifax A roared down the runway. The glider followed behind, connected by a taut rope, 350 feet long. Seconds later, the Halifax and glider drew up into the sky. Soon after, Halifax B and its glider joined them. Including air crews and sappers, there were forty-eight men on the mission.

Having observed the takeoff, Tronstad later jotted down in his diary, “Two little birds following two large ones, off towards an uncertain fate tonight.”

When Poulsson and his men arrived at the landing zone, the clear weather was changing. A moderate wind blew across the Skoland marshes, and scattered clouds hung in the sky. Visibility was still good, but knowing the Vidda, this might alter at a moment’s notice.

Leaving Haugland and Kjelstrup on a hillside to set up the Eureka beacon, Poulsson and Helberg moved down into the snow-covered marsh to mark out the landing zone. They placed six red-beamed flashlights in the snow, each 150 yards apart, in the shape of an L.

Haugland would be the first to know the Halifaxes were coming. When a plane approached, its Rebecca device would send a radio signal to his Eureka device. A tone would sound in his headset, and his Eureka would send a signal back to the Rebecca, giving the plane’s navigator a bead on their landing zone.

Everything ready, the Grouse team gathered together in the dark, certain that they could lead the sappers undetected to the target and that the defenses at Vemork would be overcome. But with each passing minute, the scattered clouds lowered, and a northwest wind rose into a scream.

At 9:40 P.M., Haugland knelt in the snow beside the Eureka. A tone sounded in his headset, and through the rising winds, he shouted to Poulsson, “I hear the Rebecca. They’re coming now.” Poulsson skied down toward the landing site. “Up with the lights,” he called out. Quickly, they lit the red L in the snow.

Poulsson stood at the corner of the L, covering and uncovering the white beam of his flashlight with his hand. Wind whipped around him. He stared skyward, the low clouds breaking occasionally to reveal the moon. Although he worried that the flashlight beams were too weak for the pilots to see through the cloud cover, he knew the Eureka radio beacon would bring them in close nonetheless.

A few minutes passed before they heard the low grumble of a Halifax approaching. “I can hear it,” Haugland cried out, his voice lost to the others. The engines grew louder. The Halifax was surely flying right above them. Spirits high, they waited for the glider to appear out of the darkness. Gradually, though, the roar of the engines faded, and Haugland’s headset went silent.

Poulsson continued to flash his signal, and the red lights continued to shine upward into the empty night. No glider. Nothing. They waited several more minutes. At last, another tone sounded in Haugland’s headset. “Number two is coming!” he called out. As before, the drone of engines cut through the night. But the sound never grew any louder, nor did any gliders come down.

Over the next hour, the Eureka toned a few more times, and they heard engines from several different directions. Then there was only silence.

Flying with the moon behind them, the crew of Halifax A found it impossible to make out where they were on their map. Every valley, mountain, and lake looked the same. By the navigator’s calculations, they should have been within twenty miles of the landing zone. But they never saw any red L on the ground, and their Rebecca was no longer working for some inexplicable reason. In sum, they were wandering in the dark, their fuel running low.

The pilot decided to turn back to Scotland. It was approaching midnight, and after almost five hours of flying, they would just make it home. Having set a new course, they found themselves enveloped in clouds at 9,000 feet. When the pilot tried to rise above them, the glider in tow behind, the Halifax failed to respond to the controls. Ice was beginning to form on the wings of both the plane and the glider.

At full throttle, engines roaring, the plane finally rose. They reached 12,000 feet, but the Halifax could not maintain either its altitude or its speed. It dropped back down into the clouds. The four propellers flung off ice in shards that crashed into the fuselage. They needed to get to a lower altitude to clear the ice or they would not make it. The pilot dipped down to 7,000 feet, but turbulence was worse in the thickening clouds at the lower altitude. The plane shook violently.

The Horsa glider rocked back and forth, surged upward, and plummeted down, its two pilots at the mercy of the towrope. The sappers in the back were hurled about in their seats. The wooden fuselage creaked and groaned as if it would be ripped apart at any moment. Then they lurched ahead one final time, and the icebound towrope snapped.

The glider came down fast, the wind shrieking through the aircraft. The men hooked arms to brace for the landing but had little hope it would do any good. Soon after breaking loose from the Halifax, they crashed into the mountains.

The pilots died instantly, the glider’s glass nose providing their bodies no protection. Six sappers perished upon impact. Of the nine who survived, most were too badly injured to move. A few managed to crawl out into the snow. The glider’s wings had been sheared off, the fuselage broken apart. Their gear had spilled out all over the mountainside, and the subzero temperatures bit at their skin. They had absolutely no idea where they were.

Halifax B had circled around the landing zone, its Rebecca device sending out its signal, but it had failed to zero in on the target close enough to release its glider. Running low on fuel, the pilot aborted the operation and decided to return to Scotland. He experienced the same treacherous thick layer of clouds as Halifax A and, at 11:40, lost his glider near Egersund on the southwest coast. He lowered altitude and crisscrossed over the valley, trying to locate it in the darkness.

Suddenly, he found himself staring straight out at a mountainside. He attempted to maneuver the Halifax away but failed. They clipped the top of the mountain with terrible force, throwing the rear gunner from the plane and killing him. Still traveling at great speed, the plane hurtled over the summit, then across a plateau littered with huge stones that tore it apart over the course of 800 yards. The bodies of its six crew members were scattered about the flaming wreckage.

Four miles away, across the valley, their glider rested on its side in a steep mountain forest, its nose sheared off, its two pilots dead. Their efforts to land in the darkness and fog had saved the lives of all but one of the fifteen sappers. As the weather worsened, the fourteen surviving Royal Engineers tended to one another’s injuries as best they could and wrapped the fatalities in their sleeping bags.

The ranking officer on the glider, Lieutenant Alexander Allen, sent a pair of his men to find help. At 5:30 A.M., a group of Norwegians and a patrol from the German garrison at Slettebø, outside Egersund, approached the crash site. Allen and the others had decided to surrender, even though they were heavily armed and could easily have surprised the dozen approaching Germans. The German lieutenant promised Allen, whose men were still dressed in their British uniforms, that they would be classified as prisoners of war and that a doctor would treat the wounded.

The fourteen sappers from the glider, some too severely injured to walk, were brought down from the mountain and boarded onto trucks. Walther Schrottberger, the captain in charge of the Slettebø garrison, did not know what to do with them. Clearly, they were British soldiers, and given that explosives, radio transmitters, Norwegian kroners, and light machine guns were collected at the crash site, they were saboteurs, too. He remembered that, according to Hitler’s orders, “no quarter should be given” to any saboteurs.

The Gestapo sent SS Second Lieutenant Otto Petersen, known as the “Red Devil,” to investigate. He wanted the sappers placed in his custody. Schrottberger instead gave him an hour to interrogate the British. One after the other, the sappers were brought before the Gestapo officer, shouted at, threatened, and beaten. They revealed only their names and ages.

Then, in the late afternoon, Schrottberger and his soldiers led the prisoners out the garrison gates to a sparsely forested valley, where they were shot, one by one. Bodies still warm, the fourteen Royal Engineers were stripped to their underwear and brought to a seaside beach, where they were buried in a shallow trench of sand.

SS Lieutenant Colonel Fehlis was furious over the rushed executions of the British soldiers. He sent a damning note to his chief in Berlin. “Unfortunately, the military authorities executed the survivors, so explanation scarcely is possible.” When it became known, on November 21, that there were nine survivors of a second glider crash, Fehlis wanted to make sure that every bit of intelligence was wrung from them. He ordered that the five saboteurs from the second downed glider who were in good enough shape to travel should be brought to Oslo, along with everything collected at the crash site. They would be interrogated, then shot. The other four survivors, all badly injured, could be executed immediately.

Fehlis already knew most of what he wanted to know. Among the gear scattered around the glider, the patrol had found a folded silk map with a planned escape route. Circled in blue: Vemork.

On that bleakest of days, November 20, Tronstad sat with Wilson in his Chiltern Court office. Nothing was certain in war, Tronstad understood. But reading through the Freshman messages, he could not help remembering the meeting with Henniker several days before the team left, when the prospects for success had been so high. Now those plans were shattered. The air crews were lost. Those brave young sappers, many of whom Tronstad had come to know at Brickendonbury Hall, were yet another terrible sacrifice in this awful war.

In silence, Tronstad and Wilson stared up at the giant map of Norway on the wall. It was dotted with symbols of operations under way by Kompani Linge. Some would go right. Others wrong. That was the nature of things. Despite the disaster of Freshman, the two men were determined to learn from it and try another way at Vemork. There was no other choice: They needed to stop its production of heavy water or the threat of greater losses — losses unimaginable if the Nazis obtained the bomb — might become real.

The two men could not know if the Germans had found out the target of the sappers’ mission. If they had, the risks for the next operation would multiply. The Nazis would crack down on any person in the area who might aid such an attempt, putting Skinnarland and the entire Grouse team in danger. Wilson made it clear to Tronstad that it was unlikely the British would try to send another big team of Royal Engineers. He and Tronstad agreed that was for the best. A small group of commandos would have the likeliest chance of slipping inside and destroying the plant, they decided. They should be Norwegian, comfortable with and able to navigate the winter terrain. They would be dropped into the mountains by parachute, if possible by the next full moon in December. They would join Grouse, hit Vemork’s heavy-water facilities, and get out.