In mid-April 1943, a military truck drove across the suspension bridge into Vemork. Secured in the truck bed was what looked like a steel drum of ordinary potash lye, an ingredient used in the electrolysis process. The drum actually contained 116 kilograms of almost pure heavy water from Berlin. It had originally been produced at Vemork.

Soon after the sabotage on February 28, a stream of Norsk Hydro company men and German officials had come to the plant to decide its fate. Some argued that it should be rebuilt. Others wanted all the salvageable equipment shipped to Berlin. Since destroying Vemork had become a “national Norwegian sport,” they contended, a new plant should be built in Germany. The Army Ordnance Office was asked for a “swift decision,” which it delivered: The cells should be repaired and the plant expanded as soon as possible at Vemork. Heavy-water facilities at two other locations should also be completed. The German command provided any materials and manpower required (including slave labor from abroad) and warned workers that if they did not revive the plant quickly enough, there would be reprisals.

By the time the secret shipment of heavy water arrived at Vemork, the round-the-clock work on the high-concentration plant was almost complete. The shipment was used to fill the new high-concentration cells, overriding the slow process of accumulating the precious substance drop by drop, and accelerating the return to production by several months. With three new stages and a number of cells added to the preliminary electrolysis process, the Germans projected that daily output would soon reach 9.75 kilograms. Given the plans to double the size of the high-concentration plant yet again, the daily yield might reach almost 20 kilograms.

On April 17, at 2 P.M., heavy water began to flow through the cascade of cells.

Three weeks later, on May 7, the Uranium Club met at the Reich Physical and Technical Institute in Berlin. The scientists were under pressure for results like never before. With German fortunes in the war deteriorating, the Allies set to retake all of North Africa, and the Soviets continuing to defeat the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front, the Nazi brass felt a desperate desire for something that would quickly turn the tide in their favor. One report stated that “rumors abound in the general German population about a new-fangled bomb. Twelve such bombs, designed on the principle of demolishing atoms, are supposedly enough to destroy a city of millions.” Worse yet, Abwehr intelligence had revealed that the Americans were on the path to creating “uranium bombs.” The German atomic program was riven by factions, and its scientists and research centers now exposed to attack by Allied bombing. They needed a breakthrough to focus their efforts.

The first item on the agenda for the May 7 meeting was heavy water. Only the previous day, at a German Academy of Aeronautical Research conference, Abraham Esau had placed part of the blame for their slow atomic progress on the recent lack of heavy water. But with Vemork back online and investigations beginning on some new methods of production, Esau felt confident they would soon have all the heavy water they needed.

Diebner was less sure there was enough to go around. He made it clear that he needed every drop for his next two experiments. His team’s most recent uranium machine (G-II), which used uranium metal cubes suspended in frozen heavy water, showed neutron production at a level one and a half times greater than any German experiment so far. The machine proved that a cube design was far superior to any other in fostering a chain reaction, he said, and at the right size, it would likely be self-sustaining.

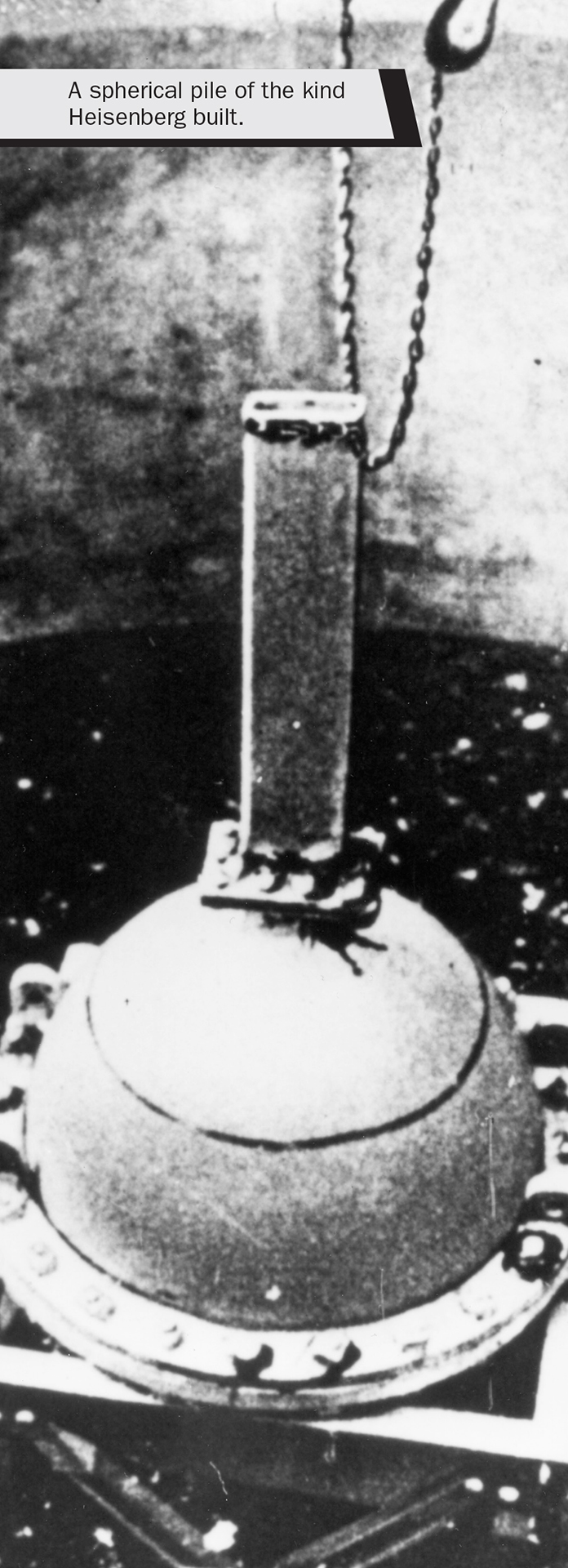

Heisenberg disagreed. In his mind, the best design was still an open question. He claimed the dimensions of his latest machine, a sphere with alternating layers of uranium metal and heavy water, were “too small to yield absolutely certain values.” But he added that the company producing uranium metal for them was already casting it in plates like he needed, rather than cubes, as Diebner demanded. Thus his experiments — and the heavy water they required — should be first in line. “This doesn’t rule out a subsequent cube experiment, if one is needed,” Heisenberg offered.

The tension in the room was sharp. Diebner had his supporters, including Harteck, who believed that Heisenberg was blind to the value of any experiment that did not originate from his own brain. Esau, who had appropriated heavy water from Heisenberg for Diebner’s latest experiment, said he needed to think further about whose work should be given precedence. Eventually, both men received a share of heavy water and uranium to allow them to proceed with small-scale experiments, but both were left dissatisfied.

On July 8, Tronstad received a message from Skinnarland: “Vemork reckons on delivering heavy water from about August 15.”

Until that point, Gunnerside had been judged an unqualified success. Their target was destroyed. Not a shot was fired. There had been no major reprisals. Every single member of the team had escaped to safety, their identities unknown to the Germans. Tronstad could not have dreamed of a better outcome. Praise came from every quarter, from the Norwegian High Command to Churchill himself. The success had raised the profile of the SOE and its Kompani Linge, giving them more opportunities for future missions in Norway. Skinnarland’s news did not blemish the Gunnerside achievement, but it was disturbing information nonetheless.

Later that month, on July 21, seven of the nine men involved in the operation had assembled in uniform in London. On behalf of King George VI, Lord Selborne awarded Rønneberg and Poulsson the Distinguished Service Order, and the others present (Helberg, Idland, Kayser, Storhaug, and Strømsheim) were given the Military Cross or Military Medal. Tronstad received the Order of the British Empire. Later, Selborne hosted a dinner for them all at the Ritz Hotel. Naturally, they ate grouse, gnawing at the bones until they were picked clean. After dinner, Tronstad took the men out on the town, the merry group singing songs as they made their way up Piccadilly. Tronstad said nothing of what he had learned from Skinnarland. He did not want to sour the evening.

Tronstad was also carrying another secret. After two German physicists visited his lab in Copenhagen, the Danish physicist Niels Bohr stated that he believed atom bombs were practicable in the immediate future, particularly if there was enough heavy water on hand to manufacture the necessary ingredients. When asked if heavy-water production was “war-important” and whether such plants should be destroyed, Bohr answered yes to both questions. Coming from Bohr, one of the fathers of atomic physics, this declaration put the bull’s-eye back on Vemork.

Tronstad sent orders to Skinnarland to investigate progress at the plant and the potential for some inside sabotage. More than anything, he wanted to prevent a massive bombing run on the plant, which the Britons’ American allies were pushing for. As he had argued several times before, he doubted such a bombardment would destroy the basement-level high-concentration plant. What was more, an attack would inflict enormous collateral damage, on both the lives of the everyday Norwegians living around the plant and the Norwegian postwar economy, which would need powerful industrial plants.

Through all this concern over heavy water, not to mention the scores of other resistance missions Tronstad was coordinating, he deeply missed his family. Their sacrifices, his own, had to be worth it. One night that summer, he tried to make sense of the struggle for his ten-year-old daughter in a letter he wrote to her:

“When we say ‘Our Fatherland,’ we mean everything we love at home: mother, little boy and you, and all the other fathers and mothers and children. It’s also all the wonderful memories from the time we ourselves were small, and from later when we had children of our own. We mean our home villages. We mean the hills, mountains and forests, the lakes and ponds, rivers and streams, waterfall and fjords. The smell of new hay in summer, of birches in spring, of the sea, and the big forest, and even the biting winter cold. Everything … Norwegian songs and music and so much, much more. That’s our Fatherland and that’s what we have to fight to get back.”

Through summer and into the fall, Haukelid and Kjelstrup championed this struggle by developing underground cells throughout western Telemark. They stressed security above all else to their seventy-five recruits: “Remember: Keep your mouth shut.” They built their own mountain hideout and established a wireless station on a nearby farm. They also scouted German positions throughout the area in preparation for the time when the Allies invaded Norway — or when their cells were called on for sabotage operations.

In late September, Haukelid and Kjelstrup received an SOE supply drop of food and weapons. But no matter how much Kjelstrup ate, he could not get over the stiffness and swelling that had plagued him since the previous winter. A doctor in Oslo had diagnosed beriberi — a disease caused by the chronic lack of the vitamin thiamine — as a result of his eating only reindeer meat for such a long stretch of time. While staying in the capital, he recovered somewhat, but his six months living back on the Vidda had caused a relapse. Kjelstrup realized he would not be able to endure another winter. He decided to cross the Swedish border and move on to Britain. The two made their farewells. When Kjelstrup cycled away, Haukelid found himself alone again.

Soon after, Haukelid closed up the cabin. With a heavy backpack on his back, he set off by foot toward Lake Møs. Approaching Nilsbu, half-hidden in fog, he was grateful that there was no shovel on the cabin roof, which would have been a warning signal telling him to keep away. Skinnarland welcomed him into the cabin.

For almost a year now, Skinnarland had largely been alone in the old reindeer hunter’s cabin. He was completely cut off from his family. His father had died during the summer, but Skinnarland dared not attend his funeral; the Gestapo was still looking for him, and it would have been an obvious chance to catch him. Moreover, his brother Torstein and friend Olav Skogen had both been captured and tortured by the Nazis for information on his whereabouts. Though he knew both men would never have accepted his surrender in exchange for their freedom, that did not soften his guilt or grief.

Skinnarland and Haukelid planned on spending the winter together. It was good to have someone to rely on, and frankly, they knew they would need each other’s company through the long, dark months. They continued to supply London with intelligence on the ramp-up of heavy-water production at Vemork, and they were ready to act to slow or stop it.

A call to action did not come.

“The powers that be wish us to consider whether we can have another go at the Vemork plant,” wrote one SOE deputy to another on October 5, 1943. Those “powers” were General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project in the United States, and Lord John Anderson of the British War Cabinet. Groves believed his scientists would have a working bomb in twelve to eighteen months, and the Germans might not be far behind. As a result, every opportunity to strike a blow against German progress must be seized. Whatever “another go” entailed, the two SOE deputies were agreed: The Norwegians, including Leif Tronstad, were against such an attack and must be excluded from further involvement in the decision.

Using the intelligence provided by Skinnarland, Colonel Wilson and his staff drew up a report with three options: (1) internal interference with production, (2) direct attacks along the lines of Gunnerside, and (3) aerial bombing. The first was deemed only a temporary solution. The second was a long shot given the new defenses at the plant. The third, if carried out during a daylight precision attack, likely offered “the best and most effective course.”

The order for the attack was sent to the head of the American 8th Air Force, General Ira Eaker. From his base at Wycombe Abbey, an hour’s drive west of London, Eaker governed a force of 185,000 men and 4,000 planes. His job was to pummel Germany into submission, chiefly by destroying its ability to fight. At first, the cigar-chomping, soft-spoken general doubted the importance of the target and resisted the mission, but by October 22, Groves made clear he wasn’t asking. Eaker informed his men, “When the weather favors attacks on Norway, the target should be destroyed.”