On the seventh morning, Martha washed his hair again, then combed it and cut it even shorter with her nail scissors. When she stared at him, she had a furrow in her brow. His mum had had a furrow in her brow and she used to tell Jake he’d put it there: all the worry of a son. He wondered what had given Martha hers.

They chopped your hair short in the Home Academy, but Martha seemed to be cutting plenty more off; he could feel it.

–Go easy, he said.

–It’ll be good for the birds, she said. –Their nests.

–I don’t care about the birds, Jake said.

Davie was watching them, and laughing. –Be a number one soon, he said. –Could work in the fracking fields with that haircut. Might end up there, you get caught. Fracky boy, fracky boy.

Jake hated Davie’s niggly voice. It made his skin itch, like some snitty insect bite. –Shove off, he said, kicking out at him.

–Don’t jerk around, or I’ll jab you with the scissors, Martha said, which just made Davie laugh harder.

–You’ve cut too much, Jake said, and he could feel Martha shake her head.

–The shorter the better. Makes you look obedient. Not like a boy who’d steal things.

Jake had emptied his rucksack out and scrubbed the mud off it, ready for the expedition. Martha gave him a second bag.

–You’re a boy doing errands for your granny. It’s her bag.

–It’s got flowers on it, he said. –I’d never carry a bag like this.

–Stuff it inside the rucksack, get it out if you need it.

–Can I bring Jet? Jake said. –He’s very obedient.

Martha shook her head. –We might have to make a run for it. I had to hide out in some toilets once. They’d have caught me if I’d had a dog.

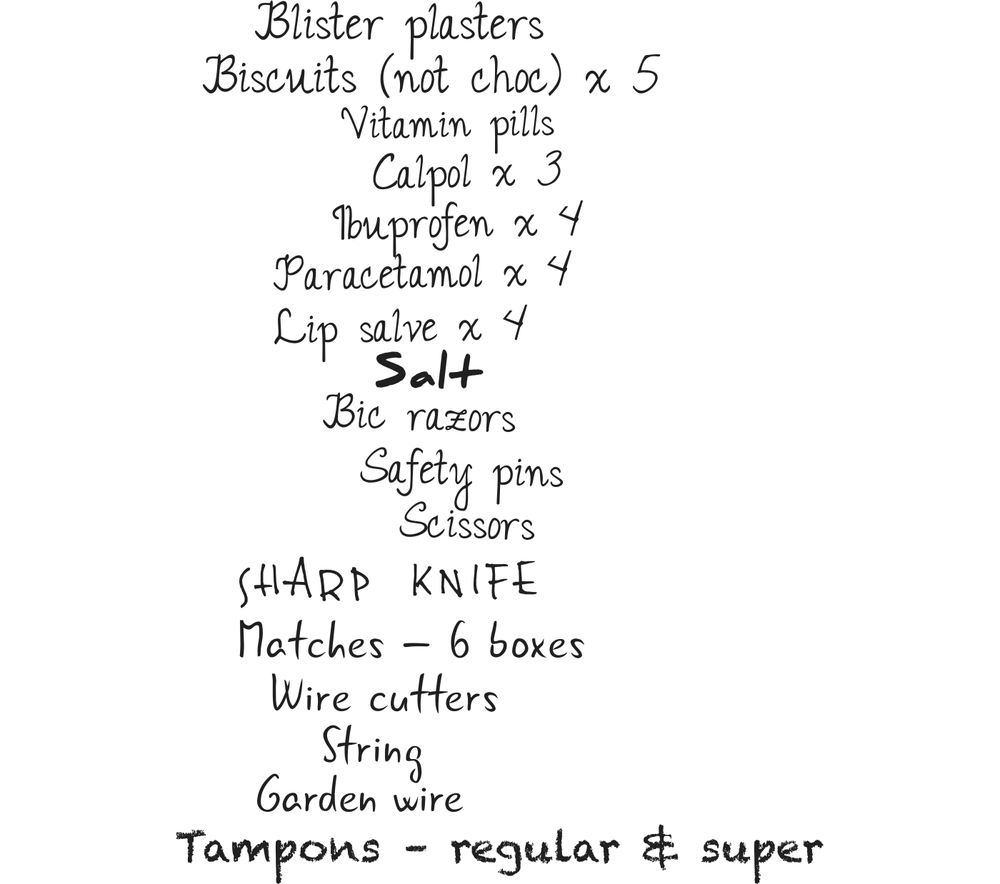

Jake read his way down the Needs list:

Cass had put the wellies on the list. Swift had printed the words out in separate letters, and Cass had copied them out underneath in green felt-tip pen, tongue between her teeth. It took her ages and Jake had felt nearly sick with memory, watching her: he used to do that with his dad when he was little. They’d had a game about who could write best, and a line of M&Ms along the kitchen table. He didn’t exactly remember how it went, but he always used to get most of the M&Ms.

–Remember, we only steal what’s on the list, Martha said. –Nothing else.

Martha had sat over Poacher’s map for an hour with Swift the night before, and then they’d shown him the route.

–Learn it off. Get it in your head, Swift said.

–Why can’t we draw it on a piece of paper? Take it with us? Jake said.

–Too risky. You get caught, that would take them straight to us.

In the morning, Jake put on his spares. He washed his hands and cleaned his fingernails as best he could. Martha wore a skirt and an old-fashioned blouse with a bow at the neck, and she did something to her hair, Jake wasn’t sure what exactly, but it fell around her shoulders in a pretty way. The sky was a dirty grey colour and she had a raincoat over her arm. They stood in the kitchen and Poacher and Swift inspected them.

–Sister and brother. What do you think? Martha said.

–Not bad. You got the same hair, Poacher said. He did up Jake’s top button and pulled his tie knot tight to his throat. –It’s your disguise. You gotta do it properly.

–Martha’s the best, Swift said. –You do what she says, you’ll come back safe.

Poacher gave them both mobiles. –For your cover. Look the business well enough.

And soon as Jake held it, he understood what Poacher meant, because it wasn’t a real mobile, it was just pretend, a toy for a toddler, made of that soft plastic they could chew on.

They set off at ten. It would take them forty minutes to walk to the shops and Martha wanted to arrive mid-morning.

–More people out and about. Makes us less conspicuous.

Forty minutes wasn’t so long, but five minutes in, it felt like for ever. They were walking down ordinary streets, in ordinary daytime. Jake hadn’t been out like this since the day he’d rescued Jet.

They walked back across the common and past the church, then down the hill, and towards the house he’d taken the clothes from. What if someone came out and they recognized the trousers and sweater? What if the other boy saw him? What then? He could feel his heart banging in his chest and his hands were sweating. He looked away as they passed the house, stared down at the road, up at the far trees, anywhere except the house with the other boy and the Santa Cruz. But nobody came out of the house, and then they were past it.

When they got to the river, Martha stopped on the bridge and leaned over the edge, so Jake did too. It was a really old stone bridge with moss and ferns growing up the sides. He looked down at the water. It was clear and he could see to the stones on the bottom, and the bits of weed swaying in the current. He watched a fish nose its way through the weeds. This river had been his escape plan a week ago, before he became an Outwalker.

Martha threw a pebble into the water. –Do you know why you got chosen for this? she said.

–No.

–I’ll tell you. It’s because you’re a watcher. You notice things. And a good thief is watching all the time, reading people’s body language. Is the shopkeeper watching you? Does she trust you? Or is she about to call the hub police? What about the other customers? If you have to make a run for it, can you get out easily? Did you notice a back way? What about alleys, car parks, churches, markets? Places where you can lose people easily. I’m a good thief because I’m a good watcher, and a fast runner.

–Even in a skirt? Jake said, because it was funny to think of Martha legging it.

She grinned too. –Absolutely.

They crossed the river and walked down Frenchay Road. There were more houses now, and there were other people walking on the pavement, and cars going past. Ordinary, hubbed people, bona fides doing ordinary things, like going to work or shopping and visiting each other.

The back of Jake’s head felt cold in the fresh air with all his hair chopped, and he had to stop himself putting his hand to it too often. He felt like he had a big sign on his head with OUTWALKER written on it in red capital letters. Surely people would take one look at him and know? The scar on his neck itched and he rubbed at it, pulling at his collar to get a finger beneath. His hair, his foraged clothes: none of it felt right. He hunched down as far as he could and kept to the inside of the pavement, running his fingers along brick walls and pebbledash, wanting to touch something fixed and solid.

Wish Jet was here, he thought, because Jet would be trotting along like he owned the place, sniffing at corners, lifting his leg on the lampposts, and then Jake could have pretended better too.

They’d been walking for fifteen minutes now and Jake’s heart was still pounding. Two boys in school uniforms walked past and they looked at him, and they noticed something, he could see they did. He rubbed at his neck again.

–Stop doing that, Martha said.

–Those boys stared at me.

–You keep scratching at your scar, then someone really will notice something.

–It’s itching, Jake said.

–I don’t care. You’ve done it five times in the last five minutes. Don’t do it again. And stop walking like an Outwalker. You’re nearly hugging the walls and you’re slouching. Behave normally.

–I don’t know what normal is.

–Then pretend. Copy me. Else you’ll get us both caught. One of the most important rules of good stealing: never show your panic. Doesn’t matter how scared you are, how much you think you stand out, how much you want to make a run for it. If you show it, people will think you’re suspicious. If you look calm, people won’t.

It crossed Jake’s mind that he’d had Martha completely wrong. He’d thought she was this mousey, scared girl. But she had nerves of steel.

–You should be in films, he said.

–What?

–Cos you can act so well. I had no idea. I thought …

–What did you think?

He hadn’t noticed before, but she was a real looker. That’s what his dad used to say and his mum used to clock him round the head for it.

–Doesn’t matter, he said, and he could feel he was blushing.

–Come on, Jake. Spit it out.

–I thought you were timid. Quiet.

She laughed and ruffled his hair, and he didn’t know if it was Martha the Outwalker doing it, or the other one, Martha the thief.

The road got busier. More people, more cars. They passed a scan hub and a bus stop, a line of people waiting, talking to tablets, checking mobiles, doing ordinary stuff. A smiling pixelated woman on the bus stop’s screen held out a plate of cupcakes. Eat English, she said, and she pushed the plate towards him before the picture morphed into a giant cockroach. ‘Use Zeet to keep the Virus at bay’, the headline read.

On another screen, a crowd of young men in green coveralls marched past. In the background there were bright green hills. ‘Your Country, Your Future’ this one said, and underneath:

Invest in your country’s future.

Good benefits package.

join@frackforfuture.gov.eng

–Same old, same old, Martha said. I swear, they haven’t changed the screens since I joined the gang.

They passed a corner shop. A couple of men outside it looked Martha up and down, the way his dad used to look at girls sometimes, and she did that normal thing girls do, which is pretend not to see them. But Jake didn’t think anyone was noticing them especially, or not him anyway, and he began to feel more normal. He got his toy mobile out and pretended to check it for something.

–That’s better, Martha said. –The mobile’s a good prop. Don’t forget to use it in a shop, like you’re checking your cash.

They were walking side by side now, and she got her list out.

–We’ll be there in a few minutes, so here’s what we do. We do a recce first, to find the shops we’re going to need. We start with the ones furthest away, and do the ones this end last, so we’re always moving towards our escape. What works best is if one of us distracts the shop assistant. Asks them to look something up, for help finding something. Then the other one can do the stealing. Stay close: that’s really important. So you can always see me, or hear me. And don’t rush. You have to think you’ve got a perfect right to be looking around the shop for things you need. And you have to think that you’re going to pay, so have your mobile out, make as if you’re credit texting. Right up until the point where you don’t. All right?

Jake nodded.

–So smile, Jake. Makes us look more innocent, in case anybody’s looking at us.

Jake nodded again and widened his mouth in what he hoped was a smile.

–You’ve got to believe in your own story while you’re out there, Martha said. –Like being an actor in a play. Else you won’t be convincing. Remember, we’re nicely brought up children, brother and sister, and we’re out doing errands for our granny.

Jake shook his head. –No. That doesn’t work. If I’ve just bunked off school to do these errands, they’ll have hubbed me, tracked me down. They did stuff like that in my old school.

Martha nodded. –Fair point. She paused. –OK. Here’s the story. Our granny’s been in hospital, and she’s still too ill to look after herself. But she’s hit the efficiency threshold for her treatment till next month, and we’re not a wealthy family. So they’ve sent her home …

–Yeah, Jake said. –That works. He could picture it now. Could imagine his own mum and dad doing this. –So the hospital has sent her home, and we’re looking after her, best we can. Our dad’s spending nights with her, and our parents are paying school absence fines for us to look after her daytimes and do her shopping. That’s why the school hasn’t hubbed us. So it’s really important that we get these things, quick as possible, and get back to her.

–Good, Martha said. –Let’s go.

The first shop was a doddle. The shop assistant wasn’t much older than Martha, and Jake saw how his face lit up when he saw her; saw him look her up and down and up again.

He’s gonna be thinking through his trousers, Jake thought. That’s what his friend Josh used to say. First time, Jake didn’t know what he meant and Josh took the piss when he asked. Josh had a big brother so he knew about these things. Anyway, Martha must’ve reckoned the same because she gave Jake the signal straight off. Jake could have stolen the whole shop and the boy wouldn’t have noticed. He was asking Martha where she’d been all his life? And did she fancy a drink later? And was she really into DIY?

Jake could hear her start on about her sick granny. He grabbed a basket and collected what he needed – wire, string, wire cutters, sharp knife, matches, even needles and thread – then nipped behind a pile of paint cans and stuck the lot in his rucksack. Job done and he was out of there, and a minute later, so was she.

–Just walk, she said. –Ahead of me. But soon as they were round the corner and out of sight, she cracked up laughing. –He was about to ask me out. I could see him trying to get up the courage.

–Worth you taking all that trouble over your hair then, he said. –Like a secret stealing weapon.

They were on a roll after that. Superdrug on Fishponds Road: medicine, plasters, vitamin pills, tampons (Martha found those). Then past KFC to the Co-Op: cooking oil, raisins, pastilles, salt, all got.

–Up here, Martha said, and she led Jake round the corner and up a quiet street.

Jake was buzzing. –I can’t believe we just walked out with all this stuff and nobody saw.

–Kids don’t nick cooking oil or salt. Not usually. That’s why they don’t notice.

–It’s like being a magician. It’s like I’ve got eyes in the back of my head. I can see what people are going to do before they do it. I can tell when they’re going to turn around and see me, when they’re going to look away. I’m invisible, slipping things into my rucksack, then out of there like a ghost … Martha? he said; because she was looking around, as if somebody was there watching them, and there was the furrow in her brow again. –You all right?

–It’s time to get out, Martha said. –I’ve got a feeling. It’s a small place and we don’t want to push our luck. We’ll get noticed soon.

Jake got what she meant. A couple of strange kids wandering about when they should be at school would get reported to the hubbers pretty quick, no matter what story they had about a granny. The hubbers would run a scan, look at the CCTV and bingo: ghost kids. There on the CCTV, but invisible on the scan hub.

–Just Cass’s wellies to get, Jake said.

Martha shook her head. –We need to go now.

Jake saw Cass at the kitchen table with the felt tip pen. It had taken her ages to write those words. That was her speaking, as close as she got.

–But she needs them, he said.

–No. We quit while we’re ahead. Also, you’re high on it, and that’s exactly when you make mistakes.

There was Cass, writing out the words: ‘Cass wellies. 12.’

–It took her ages to write them down, he said, but Martha had already turned away and she didn’t answer.

They passed another scan hub, people gathered round the news screens. Atlantic Alliance strikes deal on fisheries, Jake read on the first screen, and Chelsea storm to 2-1 victory! on the second. On a third there was a picture of a rubber boat with pieces of clothing in it. Jake could see a child’s shoe, and a life jacket. Three drown off Kent coast. What had happened to the child? Jake wondered. He peered closer to read the ticker tape: Coastguards rescue thirty drifting off Kent coast. Three die resisting arrest. All travelling without visas or exit documents. Hub police promise crackdown on illicit sale of rubber dinghies.

But it was the third one that had the biggest crowd, and he dodged between people to see the headline.

Breakthrough in Virus Vaccine: Spectacular Trial Results

He pushed further forward. This was what his parents had been doing. This was their work.

Vaccination timetable brought forward, he read. Inoculations ready for Christmas.

–Jake! Come on! Martha’s voice was quiet but urgent.

He read on down the screen, skimming the words as fast as he could. Coalition Chief Scientific Adviser … extremely effective … 100% safe antidote to lethal virus … Pandemic averted … Free … compulsory programme … children and elderly first … inoculations ready before Christmas …

He didn’t understand. His dad had said—

–Jake! Martha’s hand was on his jacket, tugging, so he turned away and followed her out. –What the hell was that about? she said.

–My mum and dad, Jake said. –They were working on the vaccine.

–My dad said the Coalition was more dangerous than the virus.

–Dangerous man to know then, your dad, Martha said.

–But the screen said—

–We need to go.