26 Actinobacillus species

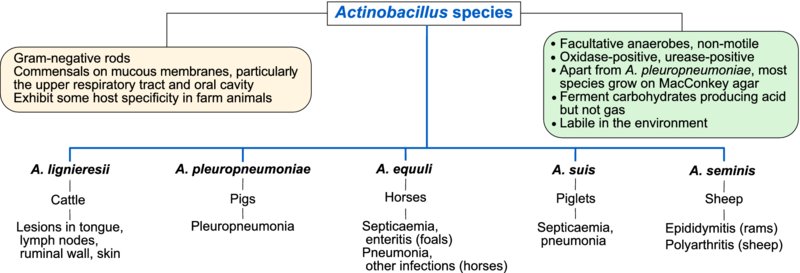

The bacteria which belong to the Actinobacillus species are non-motile, Gram-negative rods which occasionally have a coccobacillary appearence. Most species are urease-positive and oxidase-positive. Actinobacilli exhibit some host specificity and are mainly pathogens of farm animals. They are commensals on mucous membranes of animals, particularly in the upper respiratory tract and oral cavity; some species appear to be non-pathogenic and, in addition, virulence may differ between serotypes within species. Actinobacilli of veterinary importance are listed above. As these organisms survive for a short time in the environment, carrier animals play a major role in their transmission.

On primary isolation on blood agar, colonies of A. lignieresii, A. equuli and A. suis exhibit cohesive properties when touched with an inoculation loop. On MacConkey agar, A. lignieresii, A. equuli and A. suis grow well; A. equuli and A. suis ferment lactose, producing pink colonies (Table 26.1). Neither A. pleuropneumoniae nor A. seminis grow on MacConkey agar.

Table 26.1 Differentiating features of Actinobacillus species.

| Feature | A. lignieresii | A. pleuropneumoniae | A. equulia | A. suis |

| Haemolysis on sheep blood agar | – | + | v | + |

| Colony type on blood agar | Cohesive | Not cohesive | Cohesive | Cohesive |

| Growth on MacConkey agar | + | – | + | + |

| Oxidase production | + | v | + | + |

| Catalase production | + | v | v | + |

| Urease production | + | + | + | + |

aA. equuli subsp. haemolyticus is haemolytic on blood agar.

+, most isolates positive; v, variable reaction; –, most isolates negative.

Actinobacilli can cause a variety of infections in farm animals including ‘timber (wooden) tongue’ in cattle, pleuropneumonia in pigs, systemic disease in foals and piglets and epididymitis in rams.

Actinobacillosis in cattle

Actinobacillosis, a chronic pyogranulomatous inflammation of soft tissues, is most often manifest clinically in cattle as induration of the tongue, referred to as ‘timber tongue’. Lesions may also occur in the oesophageal groove and the retropharayngeal lymph nodes. The aetiological agent, A. lignieresii, is a commensal of the oral cavity and intestinal tract. The organisms enter tissues through erosions or lacerations in the mucosa and skin and consequently the disease is usually sporadic. Animals with timber tongue have difficulty in eating and drool saliva. Involvement of the tissue of the oesophageal groove can lead to intermittent tympany. Localized pyogranulomatous lesions in the retropharyngeal lymph nodes are often found at slaughter.

Diagnosis is based on the history, induration of the tongue and a background of grazing rough pasture. Specimens for laboratory examination include pus, biopsy material and tissue from lesions at postmortem. Gram-negative rods are demonstrable in smears from exudates. Pyogranulomatous foci containing club colonies may be evident in tissue sections. Cultures incubated aerobically at 37°C for 72 hours, yield small, sticky, non-haemolytic colonies on blood agar and colonies which ferment lactose slowly in MacConkey agar. The identity of isolates can be confirmed by their biochemical profile and colonial appearance. Treatment with sodium iodide parenterally, potassium iodide orally, potentiated sulphonamides or a combination of penicillin and streptomycin is usually effective.

Pleuropneumonia of pigs

Pleuropneumonia, caused by A. pleuropneumoniae, can affect susceptible pigs of all ages and occurs worldwide. This highly contagious disease affects pigs under six months of age. Virulent strains of the organism possess capsules which are both anti-phagocytic and immunogenic. Fimbriae and other adhesins allow organisms to attach to cells of the respiratory tract. In addition, A. pleuropneumoniae produces four RTX (repeat-in-toxin) toxins which damage cell membranes, iron uptake systems and, in common with other Gram-negative organisms, lipopolysaccharide.

Subclinical carrier pigs harbour the organism in their respiratory tracts and tonsils. Poor ventilation and a sudden fall in ambient temperature seem to precipitate disease outbreaks. Aerosol transmission occurs in confined groups. In outbreaks of acute disease, some pigs may be found dead while others show dyspnoea, pyrexia and a disinclination to move. Blood-stained froth may be present around the nose and mouth and many pigs are cyanotic. Pregnant sows may abort. Morbidity rates may be up to 50%, with high mortality. Concurrent infections with Pasteurella multocida and mycoplasmas may exacerbate the condition. Areas of consolidation and necrosis are found in the lungs at postmortem examination along with fibrinous pleurisy. Blood-stained froth may be present in the trachea and bronchi. Specimens for laboratory examination should include tracheal washings or affected portions of lung tissue. Specimens, cultured on chocolate agar and blood agar, are incubated in an atmosphere of 5–10% CO2 at 37°C for 72 hours. Identification criteria for isolates include small colonies surrounded by clear haemolysis and absence of growth on MacConkey agar. Biochemical tests may be used for identification of isolates but molecular methods are increasingly used for definitive typing of organisms. Fifteen serotypes and two biotypes are recognized; serotypes differ in virulence and geographical distribution. Serotypes within biotype 1 require factor V (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), supplied by chocolate agar, for growth. As cross-reactions occur between some serotypes, multiplex PCR-based methods have now been developed which are based on capsule loci and which will probably replace antibody-based testing in the future.

Chemotherapy should be based on the results of antibiotic susceptibility testing as antibiotic resistance is encountered in some strains. Polyvalent bacterins may induce protective immunity but do not prevent development of a carrier state. A subunit vaccine containing toxoids of three A. pleuropneumoniae toxins and capsular antigen has been developed. Predisposing factors such as poor ventilation, chilling and overcrowding should be avoided.

Sleepy foal disease

Two subspecies of A. equuli are recognized, subspecies equuli and subspecies haemolyticus. Subspecies equuli is associated with an acute, potentially fatal septicaemia of newborn foals, known as sleepy foal disease. Both subspecies may also be isolated from different clinical syndromes, such as respiratory disease, mastitis, metritis and arthritis, either as primary or secondary pathogens. Actinobacillus equuli is found in the reproductive and intestinal tract of mares. Foals can be infected in utero or after birth via the umbilicus. Affected foals are febrile and recumbent. Death usually occurs in one or two days. Foals which recover from the acute septicaemic phase may develop polyarthritis, nephritis, enteritis or pneumonia. Foals dying within 24 hours of birth have petechiation on serosal surfaces and enteritis. Those surviving for up to three days have typical pin-point suppurative foci in the kidneys. Although subspecies haemolyticus is known to produce an RTX toxin, other virulence factors for A. equuli have not been determined. Specimens should be cultured on blood agar and MacConkey agar. Identification criteria for isolates include sticky colonies on blood agar, lactose-fermenting colonies on MacConkey agar and biochemical profiles.

Other infections caused by actinobacilli

Actinobacillus suis can infect young pigs under three months of age. The disease is characterized by septicaemia and rapid death. Mortality may be up to 50% in some litters. Clinical signs include fever, respiratory distress and paddling of the forelimbs. Actinobacillus seminis is a common cause of epididymitis in young rams in New Zealand, Australia and South Africa. The organism is found in the prepuce, and epididymitis may follow an ascending opportunistic infection.