34 Brucella species

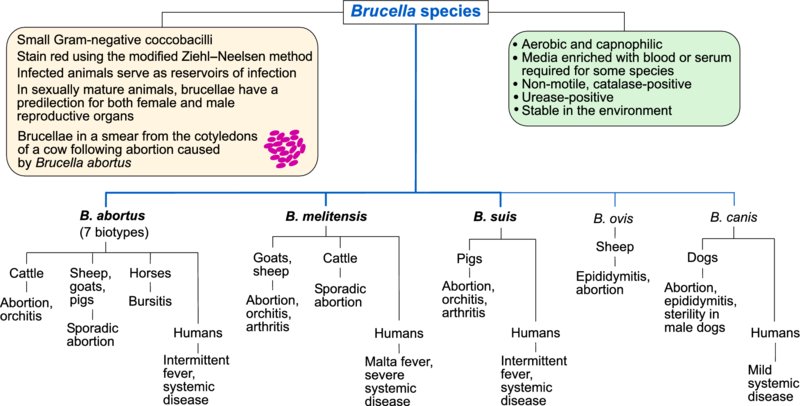

Brucella species are small, non-motile, coccobacillary, Gram-negative bacteria. As they are not decolorized by 0.5% acetic acid in the modified Ziehl–Neelsen (MZN) technique, they are classed as MZN-positive. Growth of brucellae is enhanced in an atmosphere of 5–10% CO2. Media enriched with blood or serum are required for culturing B. abortus and B. ovis. Most brucellae have a tropism for both female and male reproductive organs in sexually mature animals and each Brucella species tends to infect a particular animal species. Infected animals serve as reservoirs of infection which often persists indefinitely. Organisms shed by infected animals can remain viable in a moist environment for many months. However, indirect transmission is not of major epidemiological importance; the primary route of transmission is through ingestion of organisms from aborted foetuses and post-abortion or post-calving discharges. Venereal transmission is significant with some Brucella species.

Brucella species are differentiated by colonial appearance, biochemical tests, specific cultural requirements and growth inhibition by dyes. In addition, agglutination with monospecific sera and susceptibility to bacteriophages are employed for definitive identification. Many of the species can be divided into a number of biovars or biotypes and there may be important epidemiological differences between them. Biovars of B. suis, in particular, infect a wide range of species and are found in well-defined geographical regions.

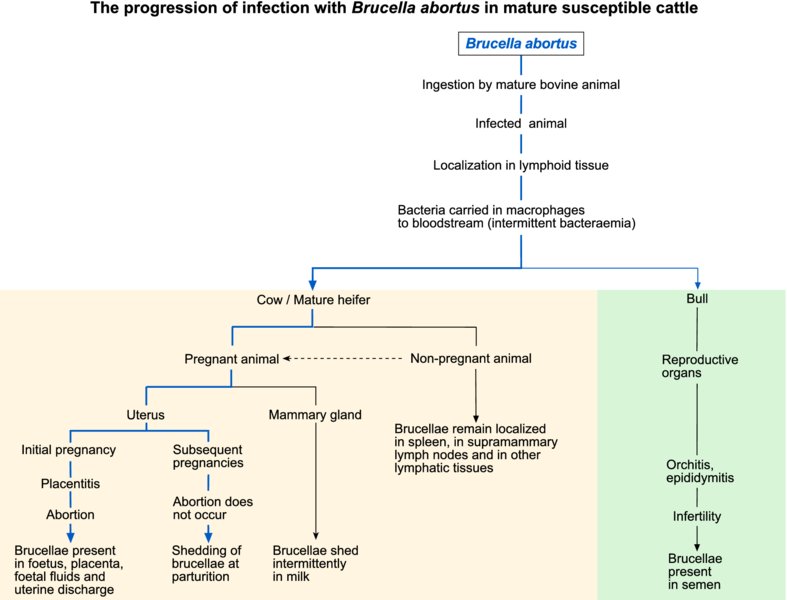

Virulent brucellae, when engulfed by phagocytes on mucous membranes, are transported to regional lymph nodes. Brucellae persist and multiply within macrophages but not within neutrophils and can also replicate in placental trophoblastic cells of pregnant animals. Both smooth and rough forms of the organism exist, the latter having defective LPS. The O-antigen of intact LPS has an important role in defence against intracellular killing; rough forms of brucellae cannot prevent fusion of lysosomes with vacuoles containing brucellae. Thus, inhibition of phagosome–lysosome function is a major mechanism for intracellular survival and an important determinant of bacterial virulence. Intermittent bacteraemia results in spread and localization in the reproductive organs and associated glands in sexually mature animals. Erythritol, a polyhydric alcohol which acts as a growth factor for brucellae, is present in high concentrations in the placentae of cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. This growth factor is also found in other organs such as the mammary gland and epididymis, which are targets for brucellae. Ten Brucella species are described, including species isolated from wildlife and marine mammals. Five of these species are of clinical significance in domestic animals and humans (Table 34.1). Although each Brucella species has its own natural host, B. abortus, B. melitensis and biotypes of B. suis can infect species of animals other than their preferred hosts.

Table 34.1 Brucella species of veterinary importance, their host range and the clinical significance of infection.

| Brucella species | Usual host / Clinical significance | Species occasionally infected / Clinical significance |

| B. abortus | Cattle / Abortion, orchitis | Sheep, goats, pigs / Sporadic abortion Horses / Bursitis Humans / Intermittent fever, systemic disease |

| B. melitensis | Goats, sheep / Abortion, orchitis, arthritis; organisms present in milk | Humans / Malta fever, severe systemic disease Cattle / Sporadic abortion, brucellae in milk |

| B. suis, biovars 1, 2 and 3 | Pigs / Abortion, orchitis, arthritis, spondylitis, infertility | Humans (biovars 1 or 3) / Intermittent fever, systemic disease |

| B. ovis | Sheep / Epididymitis in rams, sporadic abortion in ewes | |

| B. canis | Dogs / Abortion, epididymitis, discospondylitis, sterility in male dogs | Humans / Mild systemic disease |

The diagnosis of brucellosis depends on serological testing and on detection of the infecting Brucella species, either by culture or molecular methods. Care should be taken during collection and transportation of specimens, which should be processed in a biohazard cabinet. Specimens for laboratory examination should relate to the specific clinical condition encountered. MZN-stained smears from specimens, particularly cotyledons, foetal abomasal contents and uterine discharges, often reveal MZN-positive coccobacilli. In specimens containing cells, the organisms appear in clusters. A nutritious medium such as Columbia agar, supplemented with 5% serum and appropriate antimicrobial agents, is used for isolation. Most brucellae are capnophilic and accordingly plates are incubated at 37°C in 5–10% CO2 for up to five days.

Molecular tests for identification and differentiation of Brucella species are available also. The genus is remarkably homogenous and thus identification of targets that vary between species can be more difficult than with other bacterial genera. Nevertheless, a number of PCR-based techniques are available.

Serological tests are used for regulating international trade in animals and for identifying infected herds, flocks or individual animals in national eradication schemes. ELISA, brucella complement fixation tests and fluorescence polarization assay are prescribed tests for international trade. Brucellae share antigens with some other Gram-negative bacteria such as Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:9 and consequently cross-reactions can occur in agglutination tests.

With the exception of canine brucellosis, infections in animals are not treated with antimicrobial drugs. Control is based on serological testing for identification of infected animals, culling of positive reactors and vaccination. Antimicrobial therapy is employed in humans and antimicrobial resistance has not yet emerged as a problem with brucellae. Absence of plasmids and phages in these organisms may limit the opportunity for horizontal gene transfer.

Bovine brucellosis

Infection of cattle with Brucella abortus was formerly worldwide in distribution. National eradication programmes have reduced bovine brucellosis to low levels in many developed countries. Although acquired most often by ingestion, infection can occasionally follow venereal contact, penetration through skin abrasions, inhalation or transplacental transmission. Abortion storms may be encountered in herds with a high percentage of susceptible pregnant cows. Abortion usually occurs after the fifth month of gestation and subsequent pregnancies are usually carried to term. Large numbers of brucellae are excreted in foetal fluids for about two to four weeks following an abortion and at subsequent parturitions, although infected calves appear normal. Infection in calves is of limited duration, in contrast to cows, in which infection of the mammary glands and associated lymph nodes persists for many years. Brucellae may be excreted intermittently in milk for a number of years. In bulls, the structures targeted include seminal vesicles, ampullae, testicles and epididymides.

In affected herds, brucellosis can result in decreased fertility, reduced milk production, abortions in susceptible replacement animals and testicular degeneration in bulls. Abortion is a consequence of placentitis involving both cotyledons and intercotyledonary tissues. In bulls, necrotizing orchitis occasionally results in localized fibrotic lesions.

Although clinical signs are not specific for bovine brucellosis, abortions in first-calf heifers and replacement animals may suggest the presence of the disease. Clusters of MZN-positive coccobacilli may be evident in smears of cotyledons and MZN-positive organisms may also be detected in foetal abomasal contents and uterine discharges. Isolation and identification of B. abortus is confirmatory. Identification criteria for isolates include colonial appearance, MZN-positive organisms, bacterial cell agglutination with high-titre antiserum and rapid urease activity. A range of serological tests, varying in sensitivity and specificity, is available for the identification of infected animals (Table 34.2). Molecular methods such as PCR-based techniques for the detection of brucellae in tissues and fluids have been developed. National eradication schemes are based on the detection and slaughter of infected cattle. Three types of attenuated vaccines are used in cattle: strain 19 (S19) vaccine, adjuvanted 45/20 vaccine and RB51 vaccine. The S19 vaccine is administered to female calves up to five months of age. Vaccination of mature animals leads to persistent antibody titres. The 45/20 bacterin has been used in some national eradication schemes but, being a bacterin, is less effective in protecting against this intracellular pathogen. Even when administered to adult animals, this vaccine does not induce persistent antibody titres. The RB51 strain is a stable, rough mutant which induces good protection against abortion without stimulating serological responses detectable in conventional brucellosis surveillance programmes.

Table 34.2 Tests used for the diagnosis of bovine brucellosis using milk or serum.

| Test | Comments |

| Brucella milk ring test | Conducted on bulk milk samples for monitoring infections in dairy herds. Sensitive but may not be reliable in large herds due to a dilution effect |

| Rose Bengal plate test | Useful screening test. Antigen suspension is adjusted to pH 3.6, allowing agglutination by IgG1 antibodies. Qualitative test only, positive results require confirmation by CFT or ELISA |

| Complement fixation test (CFT) | Widely accepted confirmatory test for individual animals |

| Indirect ELISA | Reliable screening and confirmatory test |

| Competitive ELISA (using monoclonal antibodies) | Highly specific test; capable of detecting all immunoglobulin classes and can be used to differentiate infected animals from S19-vaccinated cattle |

| Serum agglutination test (SAT) | A tube agglutination test which lacks specificity and sensitivity; IgG1 antibodies may not be detected, leading to false-negative results |

| Antiglobulin test | Sensitive test for detecting non-agglutinating antibodies not detected by the SAT |

| Fluorescence polarization assay | Rapid test (results within minutes) which can detect all immunoglobulin classes. The test is based on detection of antibody which, if present in test serum, binds to a fragment of the O polysaccharide of Brucella labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate |

Caprine and ovine brucellosis

Brucellosis in goats and sheep, caused by B. melitensis, is most commonly encountered in countries around the Mediterranean littoral and in the Middle East, central Asia and parts of South America. Goats, in which the disease is more severe and protracted, tend to be more susceptible to infection than sheep. The clinical disease resembles brucellosis in cattle in many respects. Clinical features include high abortion rates in susceptible populations, orchitis in male animals, arthritis and hygromas. Infection resulting in abortion may not induce protective immunity.

Diagnosis is based on clinical signs, direct examination of MZN-stained smears of fluids or tissues, isolation and identification of B. melitensis and serological testing. In countries where the disease is exotic, a test and slaughter policy is usually implemented. The Rose Bengal agglutination test and the complement fixation test are the most widely used serological methods for detecting infection with B. melitensis. The modified live B. melitensis Rev. 1 strain, administered by the subcutaneous or conjunctival routes, is used for vaccination of kids and lambs up to six months of age.

Porcine brucellosis

Porcine brucellosis, caused by B. suis, occurs occasionally in the USA but is more prevalent in Latin America and Asia. Biovar 2 infection occurs in Scandanavia and the Balkans and is prevalent in wild boars throughout Europe. Infection is acquired by ingestion or by coitus and may be self-limiting in some animals. Clinical signs in sows include abortion, stillbirths, neonatal mortality and temporary sterility. Boars excreting brucellae in semen may be either clinically normal or present with testicular abnormalities. Associated sterility may be temporary or permanent. Lesions may also be found in bones and joints. The Rose Bengal plate agglutination test and the indirect ELISA are the most reliable serological methods for the diagnosis of porcine brucellosis. A test and slaughter policy is the main control measure in countries where the disease is exotic.

Canine brucellosis

Infection with Brucella canis has been recorded in dogs in the USA, UK, Japan, and Central and South America. Because of difficulties with diagnosis, the distribution of the disease may be more extensive than is currently recognized. As B. canis is permanently in the rough form, it is of comparatively low virulence, causing relatively mild and asymptomatic infections. In breeding establishments, infection may manifest clinically as abortions, decreased fertility, reduced litter sizes and neonatal mortality. Most bitches which have aborted subsequently have normal gestations. In male dogs, the main clinical feature of the disease is infertility associated with orchitis and epididymitis. Infertility may be permanent and dogs with chronic infections are often aspermic. Treatment should not be undertaken in animals intended for breeding as long-term resolution is difficult to achieve. A rapid slide agglutination test kit containing 2-mercaptoethanol is used as a screening test. Confirmatory tests include a tube agglutination test, ELISA and an agar gel immunodiffusion test. However, there are problems with the sensitivity and specificity of serological tests and definitive diagnosis can only be achieved by positive blood culture. Control is based on routine serological testing and removal of infected animals from breeding programmes.

Ovine epididymitis caused by B. ovis

Brucella ovis causes infection in sheep which is characterized by epididymitis in rams and placentitis in ewes. Infection with this pathogen, which was first recorded in New Zealand and Australia, is now present in many other countries. The consequences of infection include reduced fertility in rams, sporadic abortion in ewes and increased perinatal mortality. Brucella ovis may be present in semen about five weeks after infection and epididymal lesions can be detected by palpation at about nine weeks. In countries where the disease is endemic, pre-mating checks on rams include serological testing and scrotal palpation. The most efficient and widely used serological tests for B. ovis are the agar gel immunodiffusion test, the complement fixation test and the indirect ELISA. PCR-based tests for the detection of B. ovis in a range of clinical samples, including semen, preputial washes and urine, have been developed.

Brucellosis in humans

Humans are susceptible to infection with B. abortus, B. suis, B. melitensis and, rarely, B. canis. Transmission to humans occurs through contact with secretions or excretions of infected animals. Routes of entry include skin abrasions, inhalation and ingestion. Infection by inhalation can occur with as few as 10 organisms. Raw milk and dairy produce made with unpasteurized milk are important sources of infection. Brucellosis in humans, known as undulant fever, presents as fluctuating pyrexia, malaise, fatigue and muscle and joint pains. Abortion is not a feature of human infection. Osteomyelitis is the most common complication. Severe infection occurs with B. melitensis (Malta fever) and B. suis biovars 1 and 3. Human infections due to B. abortus are moderately severe, whereas those caused by B. canis are usually mild.