36 Spirochaetes

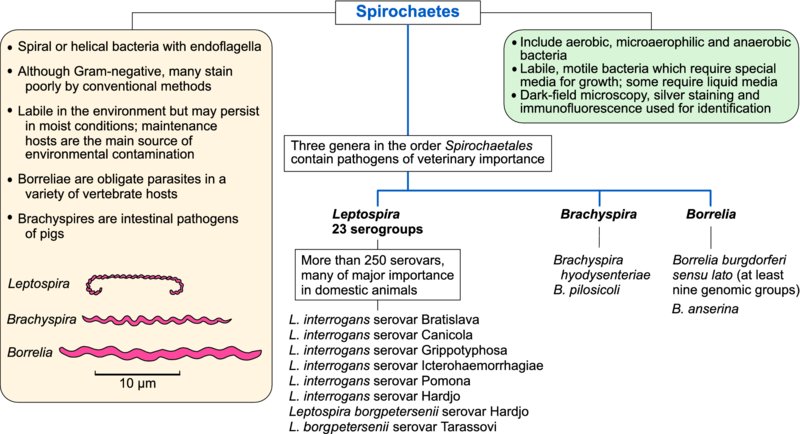

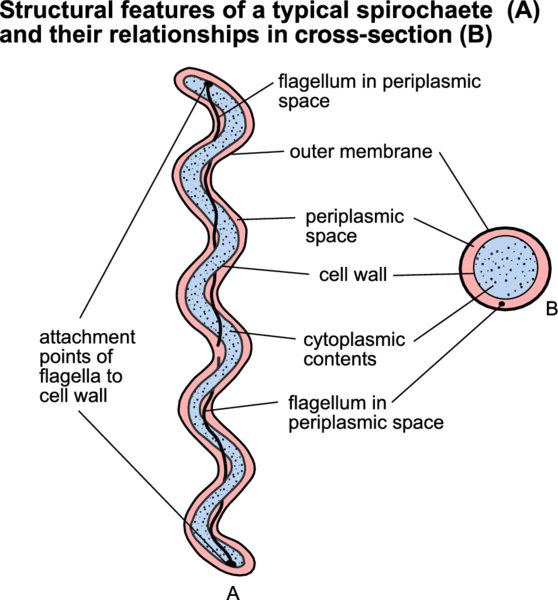

Pathogens in the family Leptospiraceae belong to the genus Leptospira. The genera Borrelia and Treponema in the family Spirochaetaceae and Brachyspira in the family Brachyspiraceae contain significant animal and human pathogens. Some non-pathogenic genera occur in each family. Pathogenic spirochaetes are difficult to culture and many require specialized media; some require liquid media.

Leptospira species

Members of this species (leptospires) are motile helical bacteria with hook-shaped ends. Although cytochemically Gram-negative, they do not stain well with conventional bacteriological dyes and dark-field microscopy is used for their detection in fluids or liquid media. Leptospirosis, which can affect all domestic animals and humans, ranges in severity from mild infections of the urinary or genital systems to serious systemic disease.

Leptospires can survive in ponds, rivers, surface waters, moist soil and mud when environmental temperatures are mild. Pathogenic leptospires can persist in the renal tubules or in the genital tract of carrier animals. These fragile organisms are transmitted most effectively by direct contact. Leptospiral species (genospecies) are classified by DNA homology. Within each species, serological reactions which identify surface antigens are employed to assign isolates to serogroups, Subsequently the organism can be further identifed to serovar level. At present, more than 250 serovars in 23 serogroups are defined, many of which may be associated with clinical disease.

Although leptospires are found worldwide, some serovars appear to have a limited geographical distribution. In addition, most serovars are associated with particular species, their maintenance hosts. The pathogenicity of leptospires relates to the virulence of the infecting serovar and the susceptibility of the host species. Maintenance hosts readily acquire infection; disease is frequently mild or subclinical and is often followed by prolonged excretion of leptospires in urine. In contrast, incidental host species are usually more resistant to infection, develop severe disease if successfully infected and are inefficient transmitters of leptospires to other animals. Leptospires invade tissues through moist softened skin or through mucous membranes. Motility and chemotaxis are essential for penetration of host tissues. The organisms spread through the body via the bloodstream but, following the appearance of antibodies about 10 days after infection, they are cleared from the circulation. Some organisms may evade the immune response and persist in the body, principally in the renal tubules and also in the uterus, eye or meninges. In susceptible animals, damage to red cell membranes and to endothelial cells, along with hepatocellular injury, produces haemoglobinuria and haemorrhage, associated with acute leptospirosis. Pulmonary haemorrhage is a significant lesion in peracute cases of disease in humans and has been documented in several animal species also.

Clinical signs, together with a history of probable exposure to contaminated urine, may indicate acute leptospirosis. Leptospires may be isolated from the blood during the first 10 days of infection and from the urine approximately two weeks after initial infection, by culture in liquid medium at 30°C but culture is a specialized technique used primarily in research. PCR-based procedures for detection and identification of organisms are now widely used in the diagnosis of disease. Fluorescent antibody procedures or silver impregnation techniques may be used for the demonstration of leptospires in tissues. The microscopic agglutination test, using live culture growth in a liquid medium, is the gold standard serological test for the diagnosis of leptospirosis. A number of ELISA tests have also been developed but none are commercially available for use in animals. The disease conditions associated with leptospiral infections in domestic animals and humans are presented in Table 36.1.

Table 36.1 Serovars of Leptospira which cause clinical infections in domestic animals and humans.

| Serovar | Hosts | Clinical conditions |

| Leptospira borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo | Cattle, sheep | Abortions, stillbirths, agalactia |

| L. interrogans serovar Hardjo | Humans | Influenza-like illness; occasionally liver or kidney disease |

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Tarassovi | Pigs | Reproductive failure, abortions, stillbirths |

| L. interrogans serovar Bratislava | Pigs, horses, dogs | Reproductive failure, abortions, stillbirths |

| L. interrogans serovar Canicola | Dogs | Acute nephritis in pups. Chronic renal disease in adult animals |

| Pigs | Abortions and stillbirths. Renal disease in young pigs | |

| L. interrogans serovar Grippotyphosa | Cattle, pigs, dogs | Septicaemic disease in young animals; abortion |

| L. interrogans serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae | Cattle, sheep, pigs | Acute septicaemic disease in calves, piglets and lambs; abortions |

| Dogs, humans | Peracute haemorrhagic disease; acute hepatitis with jaundice; human infection, Weil's disease | |

| L. interrogans serovar Pomona | Cattle, sheep | Acute haemolytic disease in calves and lambs; abortions |

| Pigs | Reproductive failure; septicaemia in piglets | |

| Horses | Abortions, periodic ophthalmia |

Leptospirosis in cattle and sheep

Cattle are maintenance hosts for L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo and this serovar may also be host-adapted for sheep. Leptospira interrogans serovar Hardjo is also host-adapted for cattle. Susceptible replacement heifers, reared separately and introduced into an infected dairy herd for the first time at calving, may develop acute disease with pyrexia and agalactia affecting all quarters. Infection may also result in abortion and stillbirths. Serovars incorporated into vaccines for use in a particular region should match leptospiral isolates from animals in that region.

Leptospirosis in horses

Leptospiral infection in horses is frequently subclinical. Clinical disease most often results from incidental infection with serovar Pomona. Signs include abortion in mares and renal disease in young horses. A recurring immune-mediated anterior uveitis (periodic ophthalmia, ‘moon blindness’) is associated with chronic leptospirosis in horses.

Leptospirosis in pigs

Acute leptospirosis in pigs is usually caused by rodent-adapted serovars such as Icterohaemorrhagiae and Copenhagenii. These serovars cause serious, sometimes fatal, disease in young pigs. In many parts of the world, the principal host-adapted serovar is Pomona. Infection can result in reproductive failure including abortions and stillbirths.

Leptospirosis in dogs and cats

Formerly, the serovars primarily associated with leptospirosis in dogs and cats were Canicola and Icterohaemorrhagiae. However, widespread vaccination against these serovars has resulted in the emergence of other serovars such as Grippotyphosa and Bratislava as causes of infection and disease. Serovar Canicola, which is host-adapted for dogs, causes severe renal disease in pups. Incidental canine infections are characterized by acute haemorrhagic disease or subacute hepatic and renal failure. Clinical leptospirosis is uncommon in cats although subclinical infection, usually acquired from rodents, occurs.

Borrelia species

Borreliae, which are longer and wider than other spirochaetes, have a similar helical shape. Although these spirochaetes can cause disease in animals and humans, subclinical infections are also common. Borreliae are transmitted by arthropod vectors. These spirochaetes are obligate parasites in a variety of vertebrate hosts and they depend on vetebrate reservoir hosts and arthropod vectors for long-term survival. Borreliae can be differentiated from other spirochaetes by their morphology, by the low guanine and cytosine content of their genomic DNA, and by ecological, cultural and biochemical features. Identification of Borrelia species depends mainly on genetic analysis. The species of particular veterinary importance are B. burgdorferi sensu lato, the cause of Lyme disease in animals and humans, and B. anserina which causes avian borreliosis (Table 36.2).

Table 36.2 Tick vectors and natural hosts of Borrelia species and associated clinical conditions.

| Species | Vector | Host | Clinical conditions |

| B. burgdorferi sensu lato | Ixodes species | Rodents, birds | Arthritic, neurological and cardiac disease in dogs and occasionally in horses, cattle, sheep. Lyme disease in humans |

| B. anserina | Argas species | Birds | Fever, weight loss and anaemia in domestic poultry |

| B. theileri | Many species of ticks | Cattle, sheep, horses | Mild, febrile disease with anaemia |

| B. coriaceae | Ornithodoros species | Cattle, deer | Associated with epizootic bovine abortion in USA |

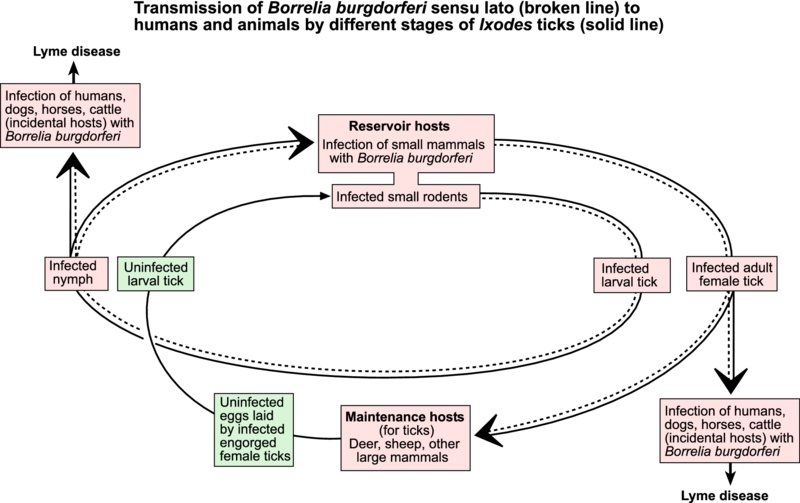

Lyme disease

This condition was first identified in 1975 following investigation of a cluster of arthritis cases in children near the town of Old Lyme, Connecticut. The causative agent, a spirochaete, was named Borrelia burgdorferi. Several genospecies of B. burgdorferi have subsequently been identified. In North America, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is the only borrelia associated with Lyme disease, whereas at least five species are known to cause disease in Europe, the most important being B. afzelii and B. garinii. Lyme disease has been reported in humans, dogs, horses and cattle, and infection has been documented in sheep.

Ticks are the only competent vectors of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. Infection is usually acquired by larval stages of ticks feeding on small rodents. The spirochaetes persist through nymphal and adult stages of ticks, which transmit infection while feeding. The persistence of these pathogenic bacteria in a region is dependent on the presence of suitable reservoir hosts for borreliae and maintenance hosts for ticks. The most common tick vector for B. burgdorferi sensu lato in Europe is Ixodes ricinus. In the USA, different Ixodes species act as vectors: I. scapularis in central and eastern regions, I. pacificus on the west coast. After entering the bloodstream of a susceptible host, borreliae multiply and are disseminated throughout the body. Organisms can be demonstrated in joints, brain, nerves, eyes and heart.

Most infections are subclinical and serological surveys demonstrate that exposure is common in both animal and human populations in endemic areas. The clinical manifestations of Lyme disease relate mainly to the sites of localization of the organisms and are largely attributed to the host's inflammatory response to the pathogen. Clinical disease is reported frequently in dogs. Signs include fever, lethargy, arthritis and evidence of cardiac, renal or neurological disturbance. The clinical signs in horses are similar to those in dogs. In cattle and sheep, lameness has been reported. Laboratory confirmation of Lyme disease may prove difficult because the spirochaetes may be present in low numbers in specimens from clinically affected animals. A history of exposure to tick infestation in an endemic area in association with characteristic clinical signs may suggest Lyme disease. Rising antibody titres to B. burgdorferi sensu lato along with typical clinical signs are indicative of disease. ELISA and immunofluorescence assays are used for antibody detection. Culture of borreliae from clinically affected animals is confirmatory. Low numbers of borreliae can be detected in samples by PCR techniques.

Acaricidal sprays, baths or dips should be used to control tick infestation. Where feasible, tick habitats such as rough brush and scrub should be cleared. A number of vaccines, including whole-cell bacterins and a recombinant subunit vaccine, are commercially available for use in dogs but their efficacy is questioned by some research workers.

Lyme disease is an important tick-borne infection of humans. Infection is often acquired by walking in endemic areas during periods of tick activity. Clinical signs include skin rash at site of tick attachment followed by arthritis, muscle pains, and cardiac and neurological complications.

Avian spirochaetosis

This acute disease of birds, caused by Borrelia anserina, can result in significant economic loss in flocks in tropical and subtropical regions. Chickens, turkeys, pheasants, ducks and geese are susceptible to infection. Soft ticks of the genus Argas frequently transmit the disease. The borreliae survive trans-stadial moulting in ticks and can be transmitted transovarially between tick generations. Outbreaks of avian spirochaetosis coincide with periods of peak tick activity during warm humid seasons. The disease is characterized by fever, marked anaemia and weight loss. Paralysis may develop as the disease progresses. Immunity, which follows recovery, is serotype-specific. Diagnosis can be confirmed by demonstration of the spirochaetes in buffy coat smears using dark-field microscopy. Giemsa-stained smears or silver impregnation techniques can be used to demonstrate the borreliae in tissues. Blood or tissue smears can be examined using immunofluorescence. Inactivated vaccines and tick eradication are the main control measures.

Brachyspira and Treponema species

Of the five genospecies of intestinal spirochaetes which have been isolated from pigs, two species, Brachyspira hyodysenteriae and B. pilosicoli, are the most pathogenic. These anaerobic spirochaetes can be differentiated by their pattern of haemolysis on blood agar, hippurate hydrolysis and by restriction endonuclease analysis. Pathogenic Brachyspira species are found in the intestinal tract of both clinically affected and normal pigs. Brachyspira pilosicoli is found in the intestines of pigs, chickens, wild birds, dogs, rodents and some non-human primates. Carrier pigs can shed B. hyodysenteriae for up to three months and are the principal source of infection for healthy pigs. Colonization is enhanced by factors in mucus with chemotactic activity for B. hyodysenteriae. Haemolytic activity, demonstrated in vitro, correlates with pathogenicity and motility is also an essential requirement for virulence.

Infections with Brachyspira species are of importance in pigs. Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, the cause of swine dysentery, and B. pilosicoli, the cause of porcine intestinal spirochaetosis, are recognized pathogens. Pigs acquire infection through exposure to contaminated faeces. Rodents and flies may act as transport hosts for the spirochaetes. Brachyspira hyodysenteriae can persist for several weeks in moist faeces. Infection with B. hyodysenteriae causes dysentery which is often encountered in weaned pigs from six to twelve weeks of age. Affected pigs lose condition and become emaciated. Appetite decreases and thirst may be evident. During recovery, there may be large amounts of mucus in the faeces. Although mortality is low, reduced weight gains due to poor food conversion causes major economic loss. The clinical signs of porcine intestinal spirochaetosis, caused by B. pilosicoli, are similar to those of swine dysentery but are less severe. Diarrhoea contains mucus rather than blood.

History, clinical signs and gross lesions may indicate swine dysentery. Blood agar incorporating antibiotics is used for the culture of Brachyspira species. Cultures are incubated anaerobically at 42°C for at least three days. Definitive identification can be made using immunofluorescence, PCR-based methods or biochemical tests. Medication of drinking water is a useful method of treatment although antimicrobial resistance is a problem in some countries. Depopulation, thorough cleaning, disinfection of premises and strict rodent control, are required for eradication of disease.

Treponemes are associated with digital dermatitis in cattle and contagious ovine digital dermatitis of sheep. Treponema paraluiscuniculi causes vent disease in rabbits.