![]()

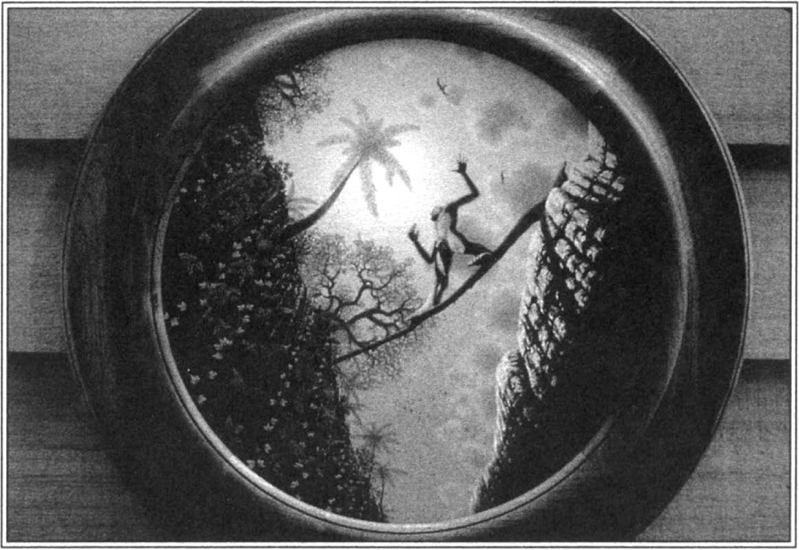

Bill Martin, Transitions, 1978; courtesy Joseph Chowning Gallery, San Francisco

It was one of those days when all his joints ached. The rains had started, and the humidity inflamed his hips and knees, especially the one he had injured long ago in his youth. He hobbled across the field, off to find something to eat and then, perhaps, to sit with a friend. Foraging for palatable food had grown more difficult as he lost more of his teeth—sometimes he spent half the day trying to appease his hunger. He paused for a moment, a bit disoriented, briefly unsure of his direction. When he was young, he had sprinted and chased and wrestled with his friends in this field.

As he resumed on the path, the two of them emerged from behind a tree, coming toward him. He tensed. They were new to the area, strangers, but not quiet like new ones usually were. Instead they were confident, making trouble for everyone. They worked together. Maybe they were brothers.

He was frightened, breathing faster. He hesitated for an instant to scratch nervously at a sudden itch on his shoulder. He glanced down, making no eye contact, as they approached, and felt a swelling of relief as they passed him. It was shortlived, as they suddenly spun around. The nearest one shoved him hard. He tried to brace himself with his bad leg but it simply wasn’t strong enough, and it buckled under him. He shrieked in fear. They leapt on him, he saw a flash of something sharp, and, in a spasm of pain, felt himself cut, slashed across his cheek and then from behind, on his back. It was over in a second and, as they ran off, leaving him on the ground, the second one yanked painfully on his tail.

![]()

As discussed in a number of earlier essays, for nearly twenty years, I have spent my summers studying the behavior and physiology of a population of wild baboons living in the grasslands of East Africa. These are smart animals with pungent, individualistic personalities, living out twenty- to twenty-five-year life spans in large social groups. I’ve been able to experience the shock of mortality in a truncated way with them—watching baboons who used to be terrors of the savannah get hobbled with arthritis, now lagging behind when the troop forages for food, or finding myself shuddering at the weathered state of a male, when he and I were both subadult primates in the 1970s when I began my work. They’ve gotten old on me.

With the graying of some of my troop, I’ve gotten the chance to understand how the quality of their later years reflects the quality of how they lived their lives. What I’ve seen is that elderly male baboons occasionally carry out a behavior that is initially puzzling, inexplicable. The reason why it occurs, as well as who carries it out, contains a lesson, I think, about how the patterns of a lifetime can come home to roost.

As discussed in “The Young and the Reckless,” most Old World primate societies, such as those of baboons, are matrilocal—females spend their entire lives in the troop into which they were born, surrounded with female relatives. Males, on the other hand, tend to leave their “natal” troop around puberty, shipping off to parts unknown, off to make their fortune in a different troop. It is a pattern common to most social species—one of the sexes has to emigrate to avoid inbreeding. And, as discussed in that essay, an odd feature of such transfers among primates is that it is voluntary, unlike in many species where males are forced out by the resident breeding male at their first sign of secondary sexual characteristics, the first sign that they are turning into sexual competitors. Primates leave voluntarily; they get this itch, a profoundly primate wanderlust that makes it feel irresistible to be anywhere that is not the drab familiar home ground. They leave, gradually make their way into a new troop, are peripheral, subordinate, unconnected, and then slowly form connections and grow into adulthood. It is a time of life fraught with danger and potential and fear and excitement.

Occasionally, a prime-aged male baboon will change troops as well. Those cases are purely career moves—some imposing competitor has just seized the number one position in the hierarchy and is likely to be there for a while, a cooperative coalition of males has just unseated you from your own position, some such strategic setback occurs—now is an expedient time to try rising on some other troop’s corporate ladder.

But what I and others have seen is that some elderly male primates will also transfer troops. This initially makes little sense, given what aging is about. This is no time of life for an animal to spend alone, unprotected in the savannah, during the limbo period of having left one troop but not yet having been assimilated into another. Senses are less acute, muscles are less willing, and predators lurk everywhere. The mortality risk for a young baboon increases two- to tenfold during the vulnerable transfer period; just imagine what it must be like for an elderly animal.

The oddity of senescent transfers becomes even more marked when considering what life will be like if the transition to the new troop is made safely. Moving into a world of strangers, of new social and ecological rules—which big, strapping males are unpredictably violent, who can be relaxed around? Which grove of trees is most likely to be fruiting when the dry season is at its worst? The new demands are made even harder given the nature of cognitive aging—“crystallized” knowledge, the recalling of facts and their application in usual, habitual ways, typically remains intact into old age, whereas declines are more common in “fluid” knowledge, the absorbing of new information and its novel and improvisatory application. It is an inauspicious time of life to try to learn new tricks.

The physical vulnerability, the emphasis on continuity, the reliance on the familiar. All this suggests that it is madness for a baboon to pick up in his old age and try a new life. Why should he ever do it?

A number of scientists, noting this odd event, have come up with some ideas. Perhaps the grass is greener in some other troop’s field, making for easier foraging. Maybe the male believes that a move is just the thing to rejuvenate his career, the chance for a brief last hurrah in some other troop. Some evidence for this idea has been found by Maria van Noordwijk and Carel van Schaik, of the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands, in their studies of macaque monkeys. One particular theory has the poignant appeal of a Hallmark card—perhaps aged males leave in order to return to their natal troop, their hometown, in order to spend their final frail years amid the care and support of their aged sisters and female relatives. As another theory, aged males may leave the troop in which they were in their prime when their daughters become of reproductive age. This would serve as a means to keep aged males from inadvertently breeding with their daughters. Susan Alberts and Jeanne Altmann of the University of Chicago have found some indirect support for this hypothesis in their baboon studies. A particularly odd twist on this idea comes from Alison Richards of Yale University in her studies of sifakas, a Madagascan primate. In a mixture of King Lear and bad Marlin Perkins, it appears to be the reproductive-age daughters who drive out the elderly fathers. No Hallmark cards there for Father’s Day.

The data from my baboons suggest an additional reason for the occasional transfer of an aged male: in many ways, the last thing you ever want to do is spend your older years in the same troop in which you were in your prime. Because the current dominant cohort treats you horribly.

When you examine the pattern of dominance interactions among the individuals in a troop, a distinctive pattern emerges. High-ranking males have their tense interactions with each other, one forcing another to give up a piece of food, a resting spot, disrupting grooming or sexual behavior. Number 3 in the hierarchy would typically have his most frequent interactions with number 2—breathing down his neck, hoping to slip in the knockout punch that ratchets him up a step in the pecking order—and with number 4, who is trying to do the same to him. Meanwhile, these high-ranking tusslers rarely bother with lowly number 20, a puny adolescent who has recently transferred into the troop (unless they are having a particularly bad day and need someone small to take it out on).

This is the general pattern regarding the frequency of dominance interactions. Inspect the matrix of interactions, though, and an odd pattern will jump out—the high-ranking males are having a zillion dominance interactions with number 14. Who’s he, what’s the big deal, why is his nose being rubbed in his subordinance at such a high rate? And it turns out that elderly number 14 used to be number 1, back when he was in his prime and the current dominant generation were squirrelly adolescents. They remember. When I examined the rare males who had transferred into my troops in their old age, they all experienced the same new world—they were utterly subordinate, sitting in the cellar of the hierarchy, but at least they were anonymous and ignored. In contrast, the males who declined in the troop in which they were in their prime were subjected to more than twice the number of dominance interactions as were the old anonymous males who had transferred in.

Why are the prime-aged males so awful and aggressive to the deposed ruling class? Are they still afraid of them, afraid that they may rise again? Do they get an ugly, visceral thrill out of being able to get away with it? It is impossible to infer what is going on in their heads. My data indicate, however, that the new generation doesn’t particularly care who the aged animal is, so long as he was once high-ranking. In theory, one might have expected a certain grim justice of what goes around comes around—males who were particularly brutal in their prime, treating young subordinates particularly aggressively, would be the ones most subject to the indignities of old age when time turned the tables. But I did not observe that pattern—the brutalizing of elderly males who remained in the troop was independent of how they went about being dominant back when. All that seemed to matter was that they once were scary and dominant. And that they no longer were.

This all seems rather sad to me, this feature of life among our close relatives—how, in one’s old age, it can be preferable to take your chances with the lions than with the members of your own species, how one might choose to rely on the kindness, or at least the indifference, of strangers.

Looking at this grim pattern, the puzzlement before—why should an elderly male ever leave the troop?—gives rise to the inverse—why should he ever stay? Yet roughly half of them do, living out their final years in the troop in which they were in their prime. Are these the ones who have held on to a protective high rank longer, who for some reason are less subject to the harassments of the next generations? My data indicated that this is not the case. Instead, the males who stayed had something unique to sustain them during the hard times—friendship.

Aging, it has been said, is often the time of life spent among strangers. Given the demographics of aging among humans, old age for a woman is often spent among strangers because she has outlived her husband. And given the typical patterns of socialization that have been documented, old age for a man in our society is often spent among strangers because he has outlived his perceived role—job-holder, breadwinner, careerist—and has discovered that he never made any true intimates along the way. Studies of gender-specific patterns of socialization have shown how much more readily women make friends than do men—they are better able to communicate in general and about emotions in particular, more apt to view cooperation and interdependence as a goal rather than as a sign of weakness, more interested in emotionally affirming each other’s problems than simply problem solving. And by old age, women and men differ dramatically in the number of friends and intimates they still have. In an interesting extension of this, Teresa Seeman and colleagues at Yale University have shown that close friendships for an older man are physiologically protective, while for a woman, it is the quality of the friendship that is important. Interpretation—intimate friendships are so rare for an older man that that in and of itself is a unique and salutary marker. In contrast, for an aged woman, intimate friends are the norm, not such a big deal in and of itself. Far too often, intimacy at that age means the woman has the enormously stressful task of taking care of someone infirm, hardly a recipe for her own successful aging. Seeman’s studies show physiological protection for the women whose intimate relationships are symmetric and reciprocal, rather than a burden.

I think there are some parallels here to the world of baboons. Females, by dint of spending their whole lives in the same troop, are surrounded by relatives and by nonrelatives with whom they’ve had decades to develop relationships. Moreover, social rank in females is hereditary and, for the most part, static over the lifetime, so the jostling and maneuvering for higher rank is not a feature in the life of a female. In contrast, a male spends his adult years in a place without relatives, typically apart from the individuals he grew up with, where the primary focus of his social interactions is often male-male competition. In such a world, it is a rare male who has friends.

To use this term is not an anthropomorphism. Male baboons do not have other males as friends—for example, over the years, I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen adult males grooming each other. The most a male can typically hope for out of another adult male is a temporary business partner in a coalition, and often an uneasy partner at that. For the rare male who has “friendships,” it is with females.

This has nothing to do with sex—shame on you for such tawdry, lascivious thoughts. It’s purely platonic, independent of where the female is in her reproductive cycle. They’re just friends. This is an individual that the male grooms a lot, and who grooms him in return. It is someone he will sit in contact with when either is troubled by some tumult in the baboon world. It is someone whose infant he will play with or carry protectively when a predator lurks.10

Barbara Smuts, of the University of Michigan, published a superb monograph a decade ago analyzing the rewards and heartbreaks of such friendships, trying to make sense of which of the rare males are capable of such stability. And she documented something that I know many baboonologists have observed in their animals: males who develop these friendships are ones who have placed a high priority on them throughout their prime adult years. These are males who would put more effort into forming affiliative friendships with females than making strategic fighting coalitions with other males. These are the baboons who maximize reproductive success through covert matings with females who prefer them, rather than through the overt matings that are the rewards of successful male-male conflict. These are males who, in the prime of life, might even have walked away from high rank, voluntarily relinquishing dominant positions, rather than having to be decisively defeated (and possibly crippled) in their Waterloo.

Work by Smuts, Craig Packer of the University of Minnesota, and Fred Bercovitch of the Caribbean Primate Center has shown that male baboons are more likely to form such affiliative relationships with females as they mellow into old age. But, to infest the world of baboons with some psychobabble, the males with the highest rates of these affiliative behaviors are the ones who made their distinctive lifestyle choices early on. And it is this prioritizing that differentiates them in their old age. When I compared males who, in their later years, remained in the same troop with those who left, the former were the ones with the long-standing female friendships—still mating, grooming, being groomed, sitting in contact with females, interacting with infants. These are the males who have worked early on to become part of a community.

A current emphasis in gerontology is on “successful aging,” the study of the surprisingly large subset of individuals who spend their later years healthy, satisfied, and productive. This is a pleasing antidote to the view of aging as nothing but the dying of the light. Of course, how successfully an individual ages can depend on the luck of the draw when it comes to genes, or the good fortune of the right socioeconomic status. Yet gerontologists now appreciate how much such successful aging also reflects how you live your daily life, long before reaching the threshold of old age. It’s not a realm where there’s much help from quick medical fixes or spates of resolutions about eating right/relaxing more/getting some exercise, starting first thing tomorrow. It is the despair of many health care professionals how difficult humans find the sorts of small, incremental daily acts that constitute good preventative medicine. It looks like when it comes to taking the small steps toward building lifelong affiliations, your average male baboon isn’t very good at this either. But the consequences for those who can appear to be considerable; there’s a world of difference between doing things today and planning to do things tomorrow.

No doubt, somewhere, there is a warehouse crammed with unsold, musty merchandise, left over when various fads of the sixties faded, cartons of cranberry-striped bell-bottoms and love beads. There may still be a market for some of that stuff: perhaps baboons might pay attention to one of those posters that we all habituated to, the horribly clichéd one about today being the first day of the rest of your life.

For a more technical treatment of this subject, see R. Sapolsky, “Why Should an Aged Male Baboon Ever Transfer Troops?” American Journal of Primatology 39 (1996): 149. Also see C. Packer, “Male Dominance and Reproductive Activity in Papio anubis,” Animal Behaviour 27 (1979): 37. Also see F. Bercovitch, “Coalition, Cooperation and Reproductive Tactics among Adult Male Baboons,” Animal Behaviour 36 (1988): 1198.

A review of crystalline and fluid knowledge with respect to aging can be found in J. Birren and K. Schaie, Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, 3rd ed. (San Diego, Calif.: Academic Press, 1990).

The work of Maria van Noordwijk and Carel van Schaik can be found in “Male Careers in Sumatran Long-Tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis),” Behavior 107 (1988): 25. The studies of Susan Alberts and Jeanne Altmann are published in “Balancing Costs and Opportunities: Dispersal in Male Baboons,” American Naturalist 145 (1995): 279. That paper also demonstrates the two- to tenfold increase in mortality when young baboons transfer. The work on sifakas is reported in A. Richards, P. Rakotomanga, and M. Schwartz, “Dispersal by Propithecus verreauxi at Beza Mahafaly, Madagascar: 1984-1991,” American Journal of Primatology 30 (1993): 1.

Gender differences in patterns of successful aging is the subject of T. Seeman, L. Berkman, D. Blazer, and J. Rowe, “Social Ties and Support and Neuroendocrine Function: The MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 16 (1994): 95. For a wonderful overview of gender differences in emotional expressivity, see Deborah Tannen’s 1990 book, You Just Don’t Understand (New York: Morrow). I firmly believe this should be required reading for all newlyweds.

Antidotes to worries about anthropomorphisms about primates: For the definitive discussion of platonic intimacy, see B. Smuts, Sex and Friendship in Baboons (New York: Aldine Publishing Company, 1985). For temperament and personality among primates, see A. Clarke and S. Boinski, “Temperament in Nonhuman Primates,” American Journal of Primatology 376 (1995): 103. Also see J. Ray and R. Sapolsky, “Styles of Male Social Behavior and Their Endocrine Correlates among High-ranking Baboons,” American Journal of Primatology 28 (1992): 231. And for an overview of cultural differences among primates, see R. Wrangham, Chimpanzee Cultures (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994).

The general and encouraging subject of aging not always being dreadful is reviewed in P. and M. Baltes, Successful Aging (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1990).