![]()

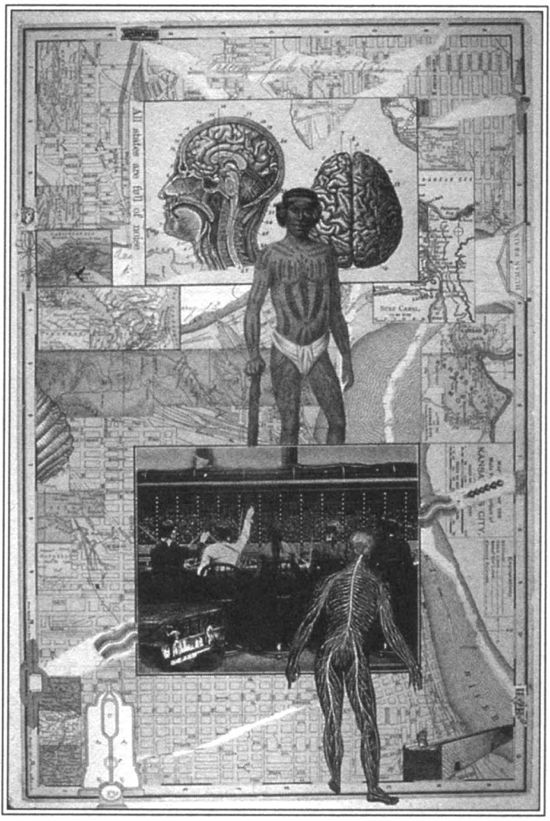

Michael Poulton, All States Are Full of Noise, 1995; courtesy the artist

Then there was the summer that I took Joseph Odhiombo’s11 blood pressure once a week and, as a result, ate like a hog.

I was spending that summer, as I had for years, living in a tent in the far corner of a game park in Kenya, conducting stress physiology research. Each week, I’d drive thirty miles to the park headquarters to get some gasoline, pick up my mail, have a soda at the tourist lodge. Joseph had recently returned to the lodge as its manager. We had met years before, when I was starting my work and he had an entry-level position in the lodge. Someone in the multinational hotel chain had spotted his competence and discipline, and Joseph had rocketed up the corporate ladder, being transferred here and there among their establishments, learning the ropes. And now he had returned triumphantly to his original lodge, the flagship of the hotel chain, its manager at the inordinately young age of forty.

We were delighted to encounter each other again. His success showed; in the previous decade, Joseph had grown plump, more than plump, a rotund man in that African status symbol, a tailored leisure suit. And he had a problem that he confessed to me on our first meeting—he was suffering from severe high blood pressure. His doctor in Nairobi was worried, as he hadn’t quite come up with a drug yet that was working. Joseph was openly anxious as to whether his life was in danger. It somehow came out that I had a blood pressure gauge, and soon I had volunteered to take his pressure each week. And so evolved our ritual.

It was one that flourished into ornate detail, as befit his role as chief of this pseudovillage. I’d arrive to find the corridor outside his office filled with excited underlings, lodge employees hoping to have their blood pressure read during the interim when I waited for Joseph to receive me. These were typically Masai tribesmen, only a few years out of the bush, who knew and cared nothing about blood pressure or heart disease, but understood that something ceremonial was happening and wanted in on it. I’d take their blood pressure—these lean, hard laborers, the baggage carriers, the gardeners, the workmen who built the place with only hand tools in the equatorial sun. Their pressure would be low, their heart rates an astonishing fifty beats a minute. To each, I’d say the same: “You are going to live to be a very old man.”

Halfway through the hoi polloi, I’d be summoned into the inner waiting room, where the indoor staffers, the guys starting up the management ladder, would be fretting, waiting to roll up the sleeves of their off-the-rack leisure suits for their readings. Their numbers would be up, nothing catastrophic, but definitely on the high side, higher readings than you’d want for someone their age—in other words, usually about the same level as my own blood pressure.

Finally, I’d be summoned into Joseph’s office. He’d greet me warmly, prepare himself under the watchful eye of his two assistant managers, there to learn the proper way to have their blood pressure taken. Silence, anticipation. And always, it would be way too high. “Joseph . . .,” I’d say, in a scolding tone. He’d deflate with worry; it still had not come down. He’d tell me hopefully about the new antihypertensive medication his doctor in Nairobi was hoping to give him; the doctor hadn’t quite gotten permission to import it into the country yet, but he was sure this one was going to help. . . . And I’d begin the next phase of our weekly ritual. “Maybe you should do some exercise, perhaps jog around the lodge a bit,” I’d tentatively venture. He’d giggle happily at the absurdity of this—“But I am the manager; I cannot be seen running around my lodge.” “Well, maybe you should go on a diet, cut back a bit.” “But what will the tourists think of the food here if the manager looks like a starving man?” I’d make a few other hopeless suggestions until Joseph’s anxiety would be subordinated to his hunger. Enough of blood pressure, he’d announce, I must join him for lunch. He would lead me into the corridor to proclaim his blood pressure to the assembled staff, who would gasp with admiration that their leader could achieve such high numbers with his heart. And then, it being impossible to say no to his enthusiastic hospitality, the two of us would descend upon the all-you-could-eat banquet, gorging with abandon.

So went that summer. Years later, as I ponder Joseph’s ill health, it strikes me that this was a man who became sick from being partially Westernized, and in a rather subtle way.

![]()

People in the developing world have became sick from being partially Westernized for a long time. Some cases represent the greatest of fears of well-meaning Western aid workers who plunge into some situation hoping to do good and instead make a mess of it. One example that has come back to haunt many a time: look at some nomadic tribe perpetually wandering around a howling wasteland of a desert searching for daily water for their goats and camels, the puddle of stagnant water here or there being all that saves them and their livestock. Obvious solution: haul in some equipment and drill a well for these folks. Expected outcome: no need to wander the desert anymore, plenty of water every day for the animals in this one convenient location. Unexpected additional outcome: the animals eat every leaf and tuft of grass within miles, and the high density of animals and their owners now encamped around the well makes communicable diseases leap through herds and through human populations with greater speed and virulence. Result: desertification, pandemics. You don’t want Western centralization of resources until you have Western resistance to diseases of high population densities.

Sometimes people in the developing world became sick from partial Westernization because their bodies work differently from those of Western populations. Think about the world of subsistence farmers eking out a living on their few tropical acres, or the nomadic pastoralists wandering the equatorial grasslands or deserts with their herds. Food and water are often scarce, unpredictable. Salt, essential for life and found in low levels in most foods other than meat, is something to trade riches for, something to go to war over. Bodies make use of these treasures mighty efficiently. Have the first smidgen of sugar and carbohydrates from a meal hit the bloodstream and the pancreas pours out insulin, ensuring that every bit of those precious nutrients is stored by the body. Similarly, the kidneys are brilliant at reabsorbing salt and thus water back into the circulation so that nothing is wasted.

Scientists have known for decades that people in the developing world are particularly good at retaining salt and water, that they often have hair-trigger metabolisms that are markedly efficient at storing circulating sugars. These highly adaptive, evolved physiologic traits are called “thrifty genes.” This represents a classic case of viewing the world through Western-colored glasses. It’s not that people in the developing world have particularly thrifty metabolisms. They have the same normal metabolisms that our ancestors did, and that nonhuman primates have. The more apt description is that Western surplus allows for the survival of individuals with sloppy genes and wasteful metabolisms.

Semantics aside, what happens when people in the developing world suddenly get access to Western diets, the newly emerging middle class of the Third World luxuriating in tap water and supermarkets stocked with processed sugars, a chicken in every pot and a saltshaker on every dinner table? Bodies that retain every bit of glucose and every pinch of salt now develop big problems. Throughout Africa, the successful middle class now suffers from a veritable plague of hypertension, hypertension known to be driven by renal water retention rather than by cardiovascular factors as is more often the case. And throughout the developing world, there are astronomically high rates of insulin-resistant, adult-onset diabetes, an archetypal Western disease of nutrient surplus—for example, among some Pacific islanders, Western diets have brought them ten times the diabetes rate found in the United States. There’s a similar, if more complex, story having to do with non-Western patterns of stomach acid secretion as a defense against oral pathogens, with the price of a greatly increased risk of ulcers once you adopt a Western lifestyle. The punch line over and over—you don’t want to receive the gift of a Western diet until you have a Westernized pancreas or kidneys or stomach lining.

Joseph and his hypertension seemed to fit this picture perfectly. But as I’ve thought more about him, I’ve become convinced that he suffered from an additional feature of partial Westernization. And this is one that I now recognize in a number of my African acquaintances—a lecturer at the university, nearly incapacitated by his stomach ulcer; an assistant warden in the game park, racked with colitis; a handful of other leisure-suited hypertensives. As a common theme, they all take their newly minted Western occupations and responsibilities immensely seriously in a place where nothing much ever works, and they haven’t a clue how to cope.

Africa is a basket case, to the endless despair of those of us who have lived there and have grown to love it and its people. Find its corners that are still untouched by the maelstroms of this century, and villagers thrive there with wondrous skill and inventiveness. But much of the rest of it is a disaster—AIDS, chloroquine-resistant malaria, and protein malnutrition; deforestation and desertification; fuel shortages and power outages; intertribal bloodbaths, numbing shuffles of military dictatorships, corrupt officials in their Mercedes gliding through seething shantytowns; Western economic manipulation, toxic pesticides dumped there because they’re too dangerous to be legal in the West, decades of homelands turned into battlegrounds for proxy superpower wars. In a setting such as that, who could possibly care that the soufflé has fallen? Yet Joseph did.

Running a lodge was a hopeless task. During peak tourist season, the front office in Nairobi would sell more rooms than existed and leave Joseph to deal with the irate tourists. The ancient generator on the freezer would expire, a spare part would be weeks away, and all the food would rot, leaving Joseph to negotiate with the local Masai to buy leathery old goats and curry them up beyond recognition for the evening dinner. The weekly petrol truck would be rolled off some bridge on the trip from Nairobi by its drunken driver, stranding all the lodge vehicles as the tourists lined up for their game drives. I’d seen plenty of other managers, before and after Joseph, hide in the curio shop, masquerade as a chef, dodge all responsibility when some major snafu occurred. But Joseph, instead, would patiently wade into the middle of each crisis, take responsibility, issue apologies, and sit worrying in his office late into the night, searching for ways to control the uncontrollable. As would my lecturer friend, trying to do his research amid no funding, the university constantly closed because of antigovernment protests. And as would the assistant warden, actually caring about the well-being of the animals while his boss was busy elephant poaching, the government going months without paying him, or his armed rangers shaking down the local populace for cash. A mountain of findings in health psychology has taught us that the same physical insult is far more likely to produce a stress-related disease if the person feels as if there is no sense of control, and no predictive information as to how long and how bad the stressor will be. And the task of trying to make the unworkable work constitutes a major occupational stressor.

It seems to me that these individuals festered in their stress-related diseases in part because their jobs, if taken seriously instead of as window dressing, were inordinately more stressful than are the equivalent ones in the West. But in addition, the truly damaging feature of their partial Westernization was that they lacked some critical means of coping. The keys to stress management involve not only gaining some sense of control or predictability in difficult situations, but also having outlets for frustration, social support, and affiliation. The frequent chaos around these men like Joseph often guaranteed little or no sense of control or predictability. And the other features were missing as well. There was no resorting to the stress-reducing outlets we take for granted.

Imagine an ambitious young turk on the fast track of some high-powered, competitive profession, working the corridors of power in the company’s headquarters in New York or L.A., someone finding the job to be increasingly stressful and abusive. What advice would you give? Go talk to the boss about the problems that need to be corrected; if need be, go over the incompetent superior’s head or make an anonymous suggestion about the changes needed. Drop out of the rat race and go back to the carpentry you’ve always been good at, or maybe answer that headhunter’s phone call and interview with some other company in the business. Get a hobby, do some regular exercise to let the steam out. Make sure you have someone to talk to—a spouse, a significant other, a friend, a therapist, a circle of people in the same business who’d understand; just make sure you’re not carrying this burden alone.

It’s an obvious list that comes to mind readily for most of us, as if we learned it in some Type A’s Outward Bound course for surviving in the canyons of the urban outback. And for the stressed white-collar professional in a place like Kenya, few of these coping mechanisms are ever considered, or would work if they were tried. Repeatedly, in conversations with Joseph and my other friends and acquaintances in his position, I would try to import some of those ideas, and slowly learned how inapplicable they were.

Businesses are run in a strictly hierarchical fashion owing much to the elder systems in many villages. (I once had a wonderfully silly conversation with a young bank officer with endless who’s-on-first-what’s-on-second confusion—Now let me get this straight, it’s your village chief who has picked out a wife for you and who tells you when is the best time for the wedding, but it’s your bank chief who tells you what you should feed the guests at the wedding, but it’s your village chief who . . .). One does not tell the boss how to run his business, one does not go over someone’s head; this is a work world without suggestion boxes. Exercise for its own stress-reducing sake is unheard of; Africa, a century behind us in the trappings of conspicuous consumption, demands that its successful men look like bloated nineteenth-century robber barons, instead of like our lean, mean sharks cutting deals on the racquetball court. Hobbies are unheard of as well; no hotel chain, worrying about its stressed executives, encourages them to take up watercolors or classical guitar.

The nouveau Westerner in the developing world also often lacks the stress relief that we feel in knowing that there are alternatives. You don’t decide to drop out, accept the smaller paycheck but at least be happy—there’s typically a village of relatives depending on your singular access to the cash economy. Furthermore, you can rarely pick up and work for the opposition—there’s only a handful of hotel chains, only one university, only one game park service; the infrastructure is still too new and small to afford many alternatives to a bad situation. And intrinsic in this is another drawback—there is less likely to be a peer group to bitch and moan with after work as an outlet, as people often have situations that are one of a kind.

The isolation and lack of social support has an even more dramatic manifestation. In a place like Kenya, the individuals who have been successes and have entered the cash economy—typically men—usually work in the capital or in one of the cities or, for some specialized job, in some distant outpost like a game park. And their wives and kids are back farming the family land in their tribal area (this pattern is so extreme that it has been remarked that Africa has evolved a form of gender-specific classism, with men forming the urban proletariat, and women, the rural peasantry). The average man in the workforce sees his family perhaps one month a year on home leave. You’ll meet men who, when asked where they live, will say the name of their tribal village, at the other end of the country, and add as an afterthought, “But I’m working now in Nairobi,” the capital—something they’ve been doing for twenty years. They just happen to spend eleven months a year temporarily sleeping near their workplace—far from their loved ones, far from the members of their tribe (a point of identification that has no remote equivalent for even the most ethnocentric of us in the West), in a country with few telephones to phone home and no such thing as quick weekend shuttle flights. And to my knowledge, there is no Westernized institution in all of Kenya that would say, “Well, given that you are such a success in the stressful position we have put you in, we’re going to come up with some bonus money for someone to farm your family land so that your wife and kids can live here with you.” There simply isn’t the mind-set for considering that solution.

Perhaps the most unsettling lack of a coping mechanism is that there is little that can be done when something bad and unfair happens, and that could happen at any moment. It was often sheer luck that launched someone successful into this new world in the first place—in a lodge, the brightest individual around might be some pot washer stuck back in the kitchen, a man with a frustrated brilliance whose poor family couldn’t pay school fees past the first few years, while the manager wound up where he was because he was the nephew of the subchief of the right tribe; no one’s heard of Horatio Alger yet. And many of the nouveau Westerners I’ve gotten to know—catapulted into the new world by luck—are diligent, capable, and meritorious. Nevertheless, those traits still won’t prevent it from all being yanked away at a moment’s notice—a superior develops a grudge, there’s another shuffle in the government and a new tribe emerges ascendant, and the job is suddenly gone. And there are few unions to defend you, few grievance boards to appeal to, no unemployment insurance. There is never the solace of knowing that there is redress, and the ground is never solid. And so, with a table filled with food each meal, with a king’s ransom of salt always available, and with worries that never subside and tomorrow always seeming uncertain, a price is eventually paid.

![]()

Strong and pragmatic words have been written about the malaise of the developing world. Some of the most trenchant and unsparing have been written about Africa by one of its own, the political scientist Ali Mazrui. He views the economic, societal-wide problems of Africa as one of partial Westernization: “We borrowed the profit motive [of the West] but not the entrepreneurial spirit. We borrowed the acquisitive appetites of capitalism but not the creative risk-taking. We are at home with Western gadgets but are bewildered by Western workshops. We wear the wristwatch but refuse to watch it for the culture of punctuality. We have learnt to parade in display, but not to drill in discipline. The West’s consumption patterns have arrived, but not necessarily the West’s technique of production.”

An author like V. S. Naipaul, another jaundiced son of the developing world, has written of the same process of partial Westernization on the individual level, his characters often lost in limbo between the new world they have not quite yet joined and the traditional one they can never return to.

And the scientists concerned with thrifty genes merely describe a more reductive version of the price of partial Westernization. To which I add my observation that you don’t want a Western lifestyle until, along with your Westernized physiology, you have Westernized techniques of stress management as well.

I once listened to a group of musicians playing in the lowest level of the labyrinthine Times Square subway station in New York, Peruvian Indians in traditional clothes, playing gorgeous Andean music with their hats out for change. Maybe these guys had already become slick New Yorkers with a good street act, but it was impossible to hear their music and not to think of the wispy memories of mountains they must have had in their heads, down there in the bowels of the urban earth.

Many of us in this country are only a few generations removed from the immigrant ancestors who made the long journey to this new world. Most who made that move would term it a success—they survived, even thrived, or at least their kids did, and they were now free of the persecution that had caused them to flee their homes. But regardless of the successes and benefits, the immigrant experience often exacted a considerable price for that first generation, the ones with only partially acculturated minds and bodies, the ones who forever carried those wispy memories of their world left behind.

After that summer of our blood pressure luncheons, Joseph was transferred to managing a different hotel, and we lost track of each other. I recently received word that his hypertension had indeed killed him, at age forty-eight. I am sorry that he is gone, as he was a good man. I hope his children will be able to experience the Western world that he gained for them more healthfully than he could. Before him, I only knew about immigrants who weathered long boat journeys in steerage in order to arrive, dislocated, in a new world. But now I realize the extent to which it is possible to be an immigrant in a dislocating new world that has journeyed to you.

The subject of thrifty genes can be found in a piece by the originator of the concept: J. Neel, “The Thrifty Genotype Revisited,” in J. Kobberling and R. Tattersall, eds., The Genetics of Diabetes Mellitus (London: Academic Press, 1982), 283. For a discussion of the hypertensive consequences of plentiful salt in the developing world, see J. Diamond, “The Saltshaker’s Curse,” Natural History, October 1991, 20.

An overview of the building blocks of coping and stress management can be found in chapters 10 and 13 of my book Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers: A Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping (New York: W. H. Freeman, 1994).

The Ali Mazrui quote is from a BBC special called The Africans. Similar sentiments occur in his book by the same title (Boston: Little, Brown, 1986).