Chapter 5

I slid behind the circulation counter and dropped my bag under the desk. That caught Julie’s eye, and she smiled at me with teeth showing, her eyes crinkled up—an aging hipster with groovy glasses and spiky hair.

“Morning. How’s it looking?” she said, slipping into the rolling chair next to mine.

I pretended to scan through the nonexistent crowd waiting for our help. “Looks like another record-breaking busy day.”

She usually laughed, but today it came out like a painful little grunt. I could actually see the smile evaporate from her face. “Huh.”

I should have said something else. Something about the weather, or politics, or war in the Middle East, or a hostage situation. Anything less charged than the empty library. “Sorry.”

“Hm.” It was all grunts now.

I pulled out a packet of gummy bears from my pocket. I offered her the package, and she rooted around until she found a green one. She put it in her mouth, but didn’t chew. It was a let-the-gummy-dissolve kind of moment, apparently.

After a few minutes, she swallowed. “City council meeting was Thursday night.”

Oops. “Was I supposed to go?”

“No. I didn’t tell you about it.”

Was there an implication there? Should I have gone without being told? Navigating the change from being the kid working in the library to being the second-in-command librarian was still occasionally a mess.

“So, how was it?”

“The city would like very much to keep the library open.” She said it while looking out the window, past the beech tree’s yellowing leaves and arching branches.

“That’s good news.” I thought about celebrating with a gummy of my own, but she was clutching the package. Tightly. In both hands.

“Hm.”

The grunts were back. Not a great sign.

“Isn’t it? Good news, I mean?” I stared at the gummies, using mind powers to make her hand the bag back. No good.

When she spoke again, it sounded rehearsed, mechanical. “They would like to keep us open, but they don’t see how it’s possible without a tax increase.”

“So, let’s have a tax increase. How much could it really cost to spit shine this old house?”

She eyed me sideways, her silent way of calling me out. “There’s a proposed increase on the ballot for November. But the bond is for a lot of money—an entirely new facility—plus the school district’s bonding for a new elementary school and playground, and people don’t want to spend more money on anything. So it’s not looking good.”

That all sounded vaguely familiar, like it was information I should have known. And maybe I did, but I hadn’t planted any of it in my memory.

The baggie disappeared in her clutch, all the air pressed out from inside. I imagined she felt similarly squeezed. Something in me felt like taking her hand, or patting her back, or saying something sympathetic. But she never really seemed like someone to touch, so I didn’t.

I put on my master’s degree voice. “Libraries are an American institution. Every community needs one.”

She gestured out the window at Pearl Street in front of us. “Family farms used to be an American institution, too. Things change.” I knew she was thinking of the tract house developments that had replaced acres of fields only a few blocks away.

I nodded, like we’d come to an agreement about something. “We’ll be great. We’ll find the money to fix up this place. Or the bond will pass. People will stand with us.”

My mind shifted from the theoretical to the practical. “What about our monthly anonymous donor?”

During all the years I’d worked in the library, and probably for a hundred years before that, we got a money order in the mail at the beginning of every month. It didn’t have a name or return address on it, but it was always two hundred dollars, and it always arrived with a typed note. Typed. On a typewriter. Like the Cards. The note always said something about the privilege it was to have such a lovely library in town and then suggested one or two book buying possibilities. Whoever our donor was, he or she hadn’t adjusted for cost of living increases. Or publication cost increases. It was the same amount every month. Two hundred dollars may not seem like much, but every single month? For years? Decades? Someone in Franklin was sharing a whole lot of cash with us.

Julie looked confused. “What about our donor?” she asked.

Wasn’t it obvious? “We have a fan. Someone thinks we’re doing something great here. So chances are good that other people think so, too.”

“Okay,” she said, still sounding like she didn’t understand.

“Can’t we ask for more donors to come forward? The zoo does it. The community theater does it. People hustle donations all the time.”

Julie sat up straighter in her chair. “We will not hustle donations.” She frowned like the idea was unspeakable, or at least uncouth.

I shrugged. “Maybe we could put up a sign.”

She shook her head. “No sign.”

“A jar?”

She put herself between me and the counter. “I absolutely forbid you to put a donations jar in this library or anywhere else.” She almost made it to the end of the sentence before she started to laugh.

“Fine. No jars. I’ll think of something else.”

I stood and grabbed a rolling cart of picture books that needed to be reshelved. Parking the cart at the bottom of the staircase, I lifted a plastic crate of books into my arms and walked up the stairs to the children’s section.

Halfway up the narrow staircase, I felt my phone vibrate. It would be imprecise to say I’d been obsessively checking for messages from Mac since dinner on Sunday. Imprecise, but not incorrect. Knowing I should get the crate of books up the stairs before I pulled my phone from my pocket did not stop me from leaning the crate against the wall and checking my texts.

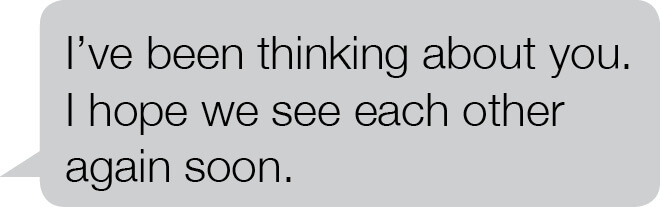

Him. It was him. Were those angels singing? (In fact, it was not. It was the ice cream man driving by on Pearl Street.)

Cheeks? Flushing. Heart rate? Elevated.

How should I reply? When should I reply? Wait—should I reply? He didn’t ask me a question. Don’t be eager, I told myself. I put the phone face up on top of the pile of books in the crate so I could keep reading the message over and over until the screen turned dark.

Focus, Greta. I took the last few stairs at a jog. Upstairs, the picture books lived on short shelves, theoretically so that any small person could reach any book. In reality, that translated to small people tossing books off every shelf at the least provocation. And strange as it sounds, I loved picking books up off the floor. I loved finding piles of books next to chairs. Knowing these books were getting loved up by kids made me glad.

A little boy in plaid shorts and an orange shirt sat on the floor looking at a book about soccer.

“Hi, buddy,” I said. “You like soccer?” Because they paid me to make conversation with four-year-olds.

He shrugged. “Soccer’s okay,” he said. “I like blue books.” Sure enough, several inches of blue-spined picture books were stacked beside him.

I sat on the floor near him. “I like blue books, too. Which one is your favorite?”

He looked at me for a second, possibly assessing my intentions. He must have found me harmless because he pushed a book toward me with a snoring dog on the cover. I picked it up and turned to the first page.

“I love this one. Have you read it?”

He looked at me like I had missed the obvious. “I just did.”

“Oh, but this one’s special. You really have to read it out loud.”

He rubbed his nose with his fist. “I only know how to read inside my imagination.”

“Lucky for you that I’m here, then,” I said, scooting a couple of inches closer. “Would you like to hear it?”

He nodded. I read.

After the first book, he handed me another.

“I’d love to read to you all day, buddy, but I have to work. How about this? I’ll put away these books, and then I’ll read you another story. My favorite from when I was a kid.”

“Okay. I’ll help you.” He clambered up off the floor and shoved his entire pile of blue books on the shelf in front of him.

Inside my head I rolled my eyes, but out loud I said thanks. And suggested a system.

He grabbed a book from the pile, I read the spine, and we shelved it together.

As I made space on a shelf for the next book on the pile, I started to realize the weight Julie was carrying. What if I was being naïve? What if the majority of people in this community actually didn’t care about the library? What if they weren’t willing to pay for it?

When we finished shelving the last of the pile, I tweeted: “Communities that read together succeed together. #KeepLibrariesOpen #GoToTheLibrary”

Then I led the kid to the R stack and pulled a battered copy of Eleanor Richtenberg’s Grimsby the Grumpy Glowworm off the shelf.

“Do you know Grimsby?”

He wrinkled up his nose. “That looks like a baby book.”

“Yeah, it looks that way. But sometimes looks can fool you. This is my favorite funny book. There are seven Grimsby books, but the first one is the best.”

By the time his mom came to find him, we’d read the book through twice, and he asked to check it out and take it home. It wasn’t even blue.