Abstract

Derivation of Ashur--Ashur as Anshar and Anu--Animal forms of Sky God--Anshar as Star God on the Celestial Mount--Isaiah’s Parable--Symbols of World God and World Hill--Dance of the Constellations and Dance of Satyrs--Goat Gods and Bull Gods--Symbols of Gods as “High Heads”--The Winged Disc--Human Figure as Soul of the Sun--Ashur as Hercules and Gilgamesh--Gods differentiated by Cults--Fertility Gods as War Gods--Ashur’s Tree and Animal forms--Ashur as Nisroch--Lightning Symbol in Disc--Ezekiel’s Reference to Life Wheel--Indian Wheel and Discus--Wheels of Shamash and Ahura-Mazda--Hittite Winged Disc--Solar Wheel causes Seasonal Changes--Bonfires to stimulate Solar Deity--Burning of Gods and Kings--Magical Ring and other Symbols of Scotland--Ashur’s Wheel of Life and Eagle Wings--King and Ashur--Ashur associated with Lunar, Fire, and Star Gods--The Osirian Clue--Hittite and Persian Influences.

The rise of Assyria brings into prominence the national god Ashur, who had been the city god of Asshur, the ancient capital. When first met with, he is found to be a complex and mystical deity, and the problem of his origin is consequently rendered exceedingly difficult. Philologists are not agreed as to the derivation of his name, and present as varied views as they do when dealing with the name of Osiris. Some give Ashur a geographical significance, urging that its original form was Aushar, “water field”; others prefer the renderings “Holy”, “the Beneficent One”, or “the Merciful One”; while not a few regard Ashur as simply a dialectic form of the name of Anshar, the god who, in the Assyrian version, or copy, of the Babylonian Creation myth, is chief of the “host of heaven”, and the father of Anu, Ea, and Enlil.

If Ashur is to be regarded as an abstract solar deity, who was developed from a descriptive place name, it follows that he had a history, like Anu or Ea, rooted in Naturalism or Animism. We cannot assume that his strictly local character was produced by modes of thought which did not obtain elsewhere. The colonists who settled at Asshur no doubt imported beliefs from some cultural area; they must have either given recognition to a god, or group of gods, or regarded the trees, hills, rivers, sun, moon, and stars, and the animals as manifestations of the “self power” of the Universe, before they undertook the work of draining and cultivating the “water field” and erecting permanent homes. Those who settled at Nineveh, for instance, believed that they were protected by the goddess Nina, the patron deity of the Sumerian city of Nina. As this goddess was also worshipped at Lagash, and was one of the many forms of the Great Mother, it would appear that in ancient times deities had a tribal rather than a geographical significance.

If the view is accepted that Ashur is Anshar, it can be urged that he was imported from Sumeria. “Out of that land (Shinar)”, according to the Biblical reference, “went forth Asshur, and builded Nineveh.”[355] Asshur, or Ashur (identical, Delitzsch and Jastrow believe, with Ashir),[356] may have been an eponymous hero--a deified king like Etana, or Gilgamesh, who was regarded as an incarnation of an ancient god. As Anshar was an astral or early form of Anu, the Sumerian city of origin may have been Erech, where the worship of the mother goddess was also given prominence.

Damascius rendered Anshar’s name as “Assōros”, a fact usually cited to establish Ashur’s connection with that deity. This writer stated that the Babylonians passed over “Sige,[357] the mother, that has begotten heaven and earth”, and made two--Apason (Apsu), the husband, and Tauthe (Tiawath or Tiamat), whose son was Moymis (Mummu). From these another progeny came forth--Lache and Lachos (Lachmu and Lachamu). These were followed by the progeny Kissare and Assōros (Kishar and Anshar), “from which were produced Anos (Anu), Illillos (Enlil) and Aos (Ea). And of Aos and Dauke (Dawkina or Damkina) was born Belos (Bel Merodach), whom they say is the Demiurge”[358] (the world artisan who carried out the decrees of a higher being).

Lachmu and Lachamu, like the second pair of the ancient group of Egyptian deities, probably symbolized darkness as a reproducing and sustaining power. Anshar was apparently an impersonation of the night sky, as his son Anu was of the day sky. It may have been believed that the soul of Anshar was in the moon as Nannar (Sin), or in a star, or that the moon and the stars were manifestations of him, and that the soul of Anu was in the sun or the firmament, or that the sun, firmament, and the wind were forms of this “self power”.

If Ashur combined the attributes of Anshar and Anu, his early mystical character may be accounted for. Like the Indian Brahma, he may have been in his highest form an impersonation, or symbol, of the “self power” or “world soul” of developed Naturalism--the “creator”, “preserver”, and “destroyer” in one, a god of water, earth, air, and sky, of sun, moon, and stars, fire and lightning, a god of the grove, whose essence was in the fig, or the fir cone, as it was in all animals. The Egyptian god Amon of Thebes, who was associated with water, earth, air, sky, sun and moon, had a ram form, and was “the hidden one”, was developed from one of the elder eight gods; in the Pyramid Texts he and his consort are the fourth pair. When Amon was fused with the specialized sun god Ra, he was placed at the head of the Ennead as the Creator. “We have traces”, says Jastrow, “of an Assyrian myth of Creation in which the sphere of creator is given to Ashur.”[359]

Before a single act of creation was conceived of, however, the early peoples recognized the eternity of matter, which was permeated by the “self power” of which the elder deities were vague phases. These were too vague, indeed, to be worshipped individually. The forms of the “self power” which were propitiated were trees, rivers, hills, or animals. As indicated in the previous chapter, a tribe worshipped an animal or natural object which dominated its environment. The animal might be the source of the food supply, or might have to be propitiated to ensure the food supply. Consequently they identified the self power of the Universe with the particular animal with which they were most concerned. One section identified the spirit of the heavens with the bull and another with the goat. In India Dyaus was a bull, and his spouse, the earth mother, Prithivi, was a cow. The Egyptian sky goddess Hathor was a cow, and other goddesses were identified with the hippopotamus, the serpent, the cat, or the vulture. Ra, the sun god, was identified in turn with the cat, the ass, the bull, the ram, and the crocodile, the various animal forms of the local deities he had absorbed. The eagle in Babylonia and India, and the vulture, falcon, and mysterious Phoenix in Egypt, were identified with the sun, fire, wind, and lightning. The animals associated with the god Ashur were the bull, the eagle, and the lion. He either absorbed the attributes of other gods, or symbolized the “Self Power” of which the animals were manifestations.

The earliest germ of the Creation myth was the idea that night was the parent of day, and water of the earth. Out of darkness and death came light and life. Life was also motion. When the primordial waters became troubled, life began to be. Out of the confusion came order and organization. This process involved the idea of a stable and controlling power, and the succession of a group of deities--passive deities and active deities. When the Babylonian astrologers assisted in developing the Creation myth, they appear to have identified with the stable and controlling spirit of the night heaven that steadfast orb the Polar Star. Anshar, like Shakespeare’s Caesar, seemed to say:

I am constant as the northern star, Of whose true-fixed and resting quality There is no fellow in the firmament. The skies are painted with unnumbered sparks; They are all fire, and every one doth shine; But there’s but one in all doth hold his place.[360]

Associated with the Polar Star was the constellation Ursa Minor, “the Little Bear”, called by the Babylonian astronomers, “the Lesser Chariot”. There were chariots before horses were introduced. A patesi of Lagash had a chariot which was drawn by asses.

The seemingly steadfast Polar Star was called “Ilu Sar”, “the god Shar”, or Anshar, “star of the height”, or “Shar the most high”. It seemed to be situated at the summit of the vault of heaven. The god Shar, therefore, stood upon the Celestial mountain, the Babylonian Olympus. He was the ghost of the elder god, who in Babylonia was displaced by the younger god, Merodach, as Mercury, the morning star, or as the sun, the planet of day; and in Assyria by Ashur, as the sun, or Regulus, or Arcturus, or Orion. Yet father and son were identical. They were phases of the One, the “self power”.

A deified reigning king was an incarnation of the god; after death he merged in the god, as did the Egyptian Unas. The eponymous hero Asshur may have similarly merged in the universal Ashur, who, like Horus, an incarnation of Osiris, had many phases or forms.

Isaiah appears to have been familiar with the Tigro-Euphratean myths about the divinity of kings and the displacement of the elder god by the younger god, of whom the ruling monarch was an incarnation, and with the idea that the summit of the Celestial mountain was crowned by the “north star”, the symbol of Anshar. “Thou shalt take up this parable”, he exclaimed, making use of Babylonian symbolism, “against the king of Babylon and say, How hath the oppressor ceased! the golden city ceased!... How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! how art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations! For thou hast said in thine heart, I will ascend unto heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God; I will sit also upon the mount of the congregation, in the sides of the north; I will ascend above the heights of the clouds; I will be like the most High.”[361] The king is identified with Lucifer as the deity of fire and the morning star; he is the younger god who aspired to occupy the mountain throne of his father, the god Shar--the Polar or North Star.

It is possible that the Babylonian idea of a Celestial mountain gave origin to the belief that the earth was a mountain surrounded by the outer ocean, beheld by Etana when he flew towards heaven on the eagle’s back. In India this hill is Mount Meru, the “world spine”, which “sustains the earth”; it is surmounted by Indra’s Valhal, or “the great city of Brahma”. In Teutonic mythology the heavens revolve round the Polar Star, which is called “Veraldar nagli”,[362] the “world spike”; while the earth is sustained by the “world tree”. The “ded” amulet of Egypt symbolized the backbone of Osiris as a world god: “ded” means “firm”, “established”;[363] while at burial ceremonies the coffin was set up on end, inside the tomb, “on a small sandhill intended to represent the Mountain of the West--the realm of the dead”.[364] The Babylonian temple towers were apparently symbols of the “world hill”. At Babylon, the Du-azaga, “holy mound”, was Merodach’s temple E-sagila, “the Temple of the High Head”. E-kur, rendered “the house or temple of the Mountain”, was the temple of Bel Enlil at Nippur. At Erech, the temple of the goddess Ishtar was E-anna, which connects her, as Nina or Ninni, with Anu, derived from “ana”, “heaven”. Ishtar was “Queen of heaven”.

Now Polaris, situated at the summit of the celestial mountain, was identified with the sacred goat, “the highest of the flock of night”.[365] Ursa Minor (the “Little Bear” constellation) may have been “the goat with six heads”, referred to by Professor Sayce.[366] The six astral goats or goat-men were supposed to be dancing round the chief goat-man or Satyr (Anshar). Even in the dialogues of Plato the immemorial belief was perpetuated that the constellations were “moving as in a dance”. Dancing began as a magical or religious practice, and the earliest astronomers saw their dancing customs reflected in the heavens by the constellations, whose movements were rhythmical. No doubt, Isaiah had in mind the belief of the Babylonians regarding the dance of their goat-gods when he foretold: “Their houses shall be full of doleful creatures; and owls (ghosts) shall dwell there, and satyrs shall dance there”.[367] In other words, there would be no people left to perform religious dances beside the “desolate houses”; the stars only would be seen dancing round Polaris.

Tammuz, like Anshar, as sentinel of the night heaven, was a goat, as was also Nin-Girsu of Lagash. A Sumerian reference to “a white kid of En Mersi (Nin-Girsu)” was translated into Semitic, “a white kid of Tammuz”. The goat was also associated with Merodach. Babylonians, having prayed to that god to take away their diseases or their sins, released a goat, which was driven into the desert. The present Polar Star, which was not, of course, the Polar star of the earliest astronomers, the world having rocked westward, is called in Arabic Al-Jedy, “the kid”. In India, the goat was connected with Agni and Varuna; it was slain at funeral ceremonies to inform the gods that a soul was about to enter heaven. Ea, the Sumerian lord of water, earth, and heaven, was symbolized as a “goat fish”. Thor, the Teutonic fertility and thunder god, had a chariot drawn by goats. It is of interest to note that the sacred Sumerian goat bore on its forehead the same triangular symbol as the Apis bull of Egypt.

Ashur was not a “goat of heaven”, but a “bull of heaven”, like the Sumerian Nannar (Sin), the moon god of Ur, Ninip of Saturn, and Bel Enlil. As the bull, however, he was, like Anshar, the ruling animal of the heavens; and like Anshar he had associated with him “six divinities of council”.

Other deities who were similarly exalted as “high heads” at various centres and at various periods, included Anu, Bel Enlil, and Ea, Merodach, Nergal, and Shamash. A symbol of the first three was a turban on a seat, or altar, which may have represented the “world mountain”. Ea, as “the world spine”, was symbolized as a column, with ram’s head, standing on a throne, beside which crouched a “goat fish”. Merodach’s column terminated in a lance head, and the head of a lion crowned that of Nergal. These columns were probably connected with pillar worship, and therefore with tree worship, the pillar being the trunk of the “world tree”. The symbol of the sun god Shamash was a disc, from which flowed streams of water; his rays apparently were “fertilizing tears”, like the rays of the Egyptian sun god Ra. Horus, the Egyptian falcon god, was symbolized as the winged solar disc.

It is necessary to accumulate these details regarding other deities and their symbols before dealing with Ashur. The symbols of Ashur must be studied, because they are one of the sources of our knowledge regarding the god’s origin and character. These include (1) a winged disc with horns, enclosing four circles revolving round a middle circle; rippling rays fall down from either side of the disc; (2) a circle or wheel, suspended from wings, and enclosing a warrior drawing his bow to discharge an arrow; and (3) the same circle; the warrior’s bow, however, is carried in his left hand, while the right hand is uplifted as if to bless his worshippers. These symbols are taken from seal cylinders.

An Assyrian standard, which probably represented the “world column”, has the disc mounted on a bull’s head with horns. The upper part of the disc is occupied by a warrior, whose head, part of his bow, and the point of his arrow protrude from the circle. The rippling water rays are V-shaped, and two bulls, treading river-like rays, occupy the divisions thus formed. There are also two heads--a lion’s and a man’s--with gaping mouths, which may symbolize tempests, the destroying power of the sun, or the sources of the Tigris and Euphrates.

Jastrow regards the winged disc as “the purer and more genuine symbol of Ashur as a solar deity”. He calls it “a sun disc with protruding rays”, and says: “To this symbol the warrior with the bow and arrow was added--a despiritualization that reflects the martial spirit of the Assyrian empire”.[368]

The sun symbol on the sun boat of Ra encloses similarly a human figure, which was apparently regarded as the soul of the sun: the life of the god was in the “sun egg”. In an Indian prose treatise it is set forth: “Now that man in yonder orb (the sun) and that man in the right eye truly are no other than Death (the soul). His feet have stuck fast in the heart, and having pulled them out he comes forth; and when he comes forth then that man dies; whence they say of him who has passed away, ‘he has been cut off (his life or life string has been severed)’.”[369] The human figure did not indicate a process of “despiritualization” either in Egypt or in India. The Horus “winged disc” was besides a symbol of destruction and battle, as well as of light and fertility. Horus assumed that form in one legend to destroy Set and his followers.[370] But, of course, the same symbols may not have conveyed the same ideas to all peoples. As Blake put it:

What to others a trifle appears Fills me full of smiles and tears.... With my inward Eye, ‘t is an old Man grey, With my outward, a Thistle across my way.

Indeed, it is possible that the winged disc meant one thing to an Assyrian priest, and another thing to a man not gifted with what Blake called “double vision”.

What seems certain, however, is that the archer was as truly solar as the “wings” or “rays”. In Babylonia and Assyria the sun was, among other things, a destroyer from the earliest times. It is not surprising, therefore, to find that Ashur, like Merodach, resembled, in one of his phases, Hercules, or rather his prototype Gilgamesh. One of Gilgamesh’s mythical feats was the slaying of three demon birds. These may be identical with the birds of prey which Hercules, in performing his sixth labour, hunted out of Stymphalus.[371] In the Greek Hipparcho-Ptolemy star list Hercules was the constellation of the “Kneeler”, and in Babylonian-Assyrian astronomy he was (as Gilgamesh or Merodach) “Sarru”, “the king”. The astral “Arrow” (constellation of Sagitta) was pointed against the constellations of the “Eagle”, “Vulture”, and “Swan”. In Phoenician astronomy the Vulture was “Zither” (Lyra), a weapon with which Hercules (identified with Melkarth) slew Linos, the musician. Hercules used a solar arrow, which he received from Apollo. In various mythologies the arrow is associated with the sun, the moon, and the atmospheric deities, and is a symbol of lightning, rain, and fertility, as well as of famine, disease, war, and death. The green-faced goddess Neith of Libya, compared by the Greeks to Minerva, carries in one hand two arrows and a bow.[372] If we knew as little of Athena (Minerva), who was armed with a lance, a breastplate made of the skin of a goat, a shield, and helmet, as we do of Ashur, it might be held that she was simply a goddess of war. The archer in the sun disc of the Assyrian standard probably represented Ashur as the god of the people--a deity closely akin to Merodach, with pronounced Tammuz traits, and therefore linking with other local deities like Ninip, Nergal, and Shamash, and partaking also like these of the attributes of the elder gods Anu, Bel Enlil, and Ea.

All the other deities worshipped by the Assyrians were of Babylonian origin. Ashur appears to have differed from them just as one local Babylonian deity differed from another. He reflected Assyrian experiences and aspirations, but it is difficult to decide whether the sublime spiritual aspect of his character was due to the beliefs of alien peoples, by whom the early Assyrians were influenced, or to the teachings of advanced Babylonian thinkers, whose doctrines found readier acceptance in a “new country” than among the conservative ritualists of ancient Sumerian and Akkadian cities. New cults were formed from time to time in Babylonia, and when they achieved political power they gave a distinctive character to the religion of their city states. Others which did not find political support and remained in obscurity at home, may have yet extended their influence far and wide. Buddhism, for instance, originated in India, but now flourishes in other countries, to which it was introduced by missionaries. In the homeland it was submerged by the revival of Brahmanism, from which it sprung, and which it was intended permanently to displace. An instance of an advanced cult suddenly achieving prominence as a result of political influence is afforded by Egypt, where the fully developed Aton religion was embraced and established as a national religion by Akhenaton, the so-called “dreamer”. That migrations were sometimes propelled by cults, which sought new areas in which to exercise religious freedom and propagate their beliefs, is suggested by the invasion of India at the close of the Vedic period by the “later comers”, who laid the foundations of Brahmanism. They established themselves in Madhyadesa, “the Middle Country”, “the land where the Brahmanas and the later Samhitas were produced”. From this centre went forth missionaries, who accomplished the Brahmanization of the rest of India.[373]

It may be, therefore, that the cult of Ashur was influenced in its development by the doctrines of advanced teachers from Babylonia, and that Persian Mithraism was also the product of missionary efforts extended from that great and ancient cultural area. Mitra, as has been stated, was one of the names of the Babylonian sun god, who was also a god of fertility. But Ashur could not have been to begin with merely a battle and solar deity. As the god of a city state he must have been worshipped by agriculturists, artisans, and traders; he must have been recognized as a deity of fertility, culture, commerce, and law. Even as a national god he must have made wider appeal than to the cultured and ruling classes. Bel Enlil of Nippur was a “world god” and war god, but still remained a local corn god.

Assyria’s greatness was reflected by Ashur, but he also reflected the origin and growth of that greatness. The civilization of which he was a product had an agricultural basis. It began with the development of the natural resources of Assyria, as was recognized by the Hebrew prophet, who said: “Behold, the Assyrian was a cedar in Lebanon with fair branches.... The waters made him great, the deep set him up on high with her rivers running round about his plants, and sent out her little rivers unto all the trees of the field. Therefore his height was exalted above all the trees of the field, and his boughs were multiplied, and his branches became long because of the multitude of waters when he shot forth. All the fowls of heaven made their nests in his boughs, and under his branches did all the beasts of the field bring forth their young, and under his shadow dwelt all great nations. Thus was he fair in his greatness, in the length of his branches; for his root was by great waters. The cedars in the garden of God could not hide him: the fir trees were not like his boughs, and the chestnut trees were not like his branches; nor any tree in the garden of God was like unto him in his beauty.”[374]

Asshur, the ancient capital, was famous for its merchants. It is referred to in the Bible as one of the cities which traded with Tyre “in all sorts of things, in blue clothes, and broidered work, and in chests of rich apparel, bound with cords, and made of cedar”.[375]

As a military power, Assyria’s name was dreaded. “Behold,” Isaiah said, addressing King Hezekiah, “thou hast heard what the kings of Assyria have done to all lands by destroying them utterly.”[376] The same prophet, when foretelling how Israel would suffer, exclaimed: “O Assyrian, the rod of mine anger, and the staff in their hand is mine indignation. I will send him against an hypocritical nation, and against the people of my wrath will I give him a charge, to take the spoil, and to take the prey, and to tread them down like the mire of the streets.”[377]

We expect to find Ashur reflected in these three phases of Assyrian civilization. If we recognize him in the first place as a god of fertility, his other attributes are at once included. A god of fertility is a corn god and a water god. The river as a river was a “creator” (p. 29), and Ashur was therefore closely associated with the “watery place”, with the canals or “rivers running round about his plants”. The rippling water-rays, or fertilizing tears, appear on the solar discs. As a corn god, he was a god of war. Tammuz’s first act was to slay the demons of winter and storm, as Indra’s in India was to slay the demons of drought, and Thor’s in Scandinavia was to exterminate the frost giants. The corn god had to be fed with human sacrifices, and the people therefore waged war against foreigners to obtain victims. As the god made a contract with his people, he was a deity of commerce; he provided them with food and they in turn fed him with offerings.

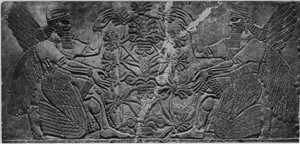

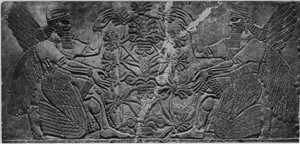

Figure XIV.1. WINGED DEITIES KNEELING BESIDE A SACRED TREE

Marble Slab from N.W. Palace of Nimroud; now in British Museum

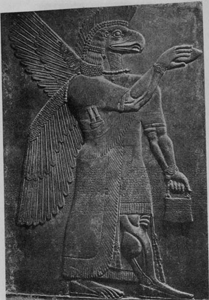

Figure XIV.2. EAGLE-HEADED WINGED DEITY (ASHUR) Marble Slab, British Museum

In Ezekiel’s comparison of Assyria to a mighty tree, there is no doubt a mythological reference. The Hebrew prophets invariably utilized for their poetic imagery the characteristic beliefs of the peoples to whom they made direct reference. The “owls”, “satyrs”, and “dragons” of Babylon, mentioned by Isaiah, were taken from Babylonian mythology, as has been indicated. When, therefore, Assyria is compared to a cedar, which is greater than fir or chestnut, and it is stated that there are nesting birds in the branches, and under them reproducing beasts of the field, and that the greatness of the tree is due to “the multitude of waters”, the conclusion is suggested that Assyrian religion, which Ashur’s symbols reflect, included the worship of trees, birds, beasts, and water. The symbol of the Assyrian tree--probably the “world tree” of its religion--appears to be “the rod of mine anger ... the staff in their hand”; that is, the battle standard which was a symbol of Ashur. Tammuz and Osiris were tree gods as well as corn gods.

Now, as Ashur was evidently a complex deity, it is futile to attempt to read his symbols without giving consideration to the remnants of Assyrian mythology which are found in the ruins of the ancient cities. These either reflect the attributes of Ashur, or constitute the material from which he evolved.

As Layard pointed out many years ago, the Assyrians had a sacred tree which became conventionalized. It was “an elegant device, in which curved branches, springing from a kind of scroll work, terminated in flowers of graceful form. As one of the figures last described[378] was turned, as if in act of adoration, towards this device, it was evidently a sacred emblem; and I recognized in it the holy tree, or tree of life, so universally adored at the remotest period in the East, and which was preserved in the religious systems of the Persians to the final overthrow of their Empire.... The flowers were formed by seven petals.”[379]

This tree looks like a pillar, and is thrice crossed by conventionalized bull’s horns tipped with ring symbols which may be stars, the highest pair of horns having a larger ring between them, but only partly shown as if it were a crescent. The tree with its many “sevenfold” designs may have been a symbol of the “Sevenfold-one-are-ye” deity. This is evidently the Assyrian tree which was called “the rod” or “staff”.

What mythical animals did this tree shelter? Layard found that “the four creatures continually introduced on the sculptured walls”, were “a man, a lion, an ox, and an eagle”.[380]

In Sumeria the gods were given human form, but before this stage was reached the bull symbolized Nannar (Sin), the moon god, Ninip (Saturn, the old sun), and Enlil, while Nergal was a lion, as a tribal sun god. The eagle is represented by the Zu bird, which symbolized the storm and a phase of the sun, and was also a deity of fertility. On the silver vase of Lagash the lion and eagle were combined as the lion-headed eagle, a form of Nin-Girsu (Tammuz), and it was associated with wild goats, stags, lions, and bulls. On a mace head dedicated to Nin-Girsu, a lion slays a bull as the Zu bird slays serpents in the folk tale, suggesting the wars of totemic deities, according to one “school”, and the battle of the sun with the storm clouds according to another. Whatever the explanation may be of one animal deity of fertility slaying another, it seems certain that the conflict was associated with the idea of sacrifice to procure the food supply.

In Assyria the various primitive gods were combined as a winged bull, a winged bull with human head (the king’s), a winged lion with human head, a winged man, a deity with lion’s head, human body, and eagle’s legs with claws, and also as a deity with eagle’s head and feather headdress, a human body, wings, and feather-fringed robe, carrying in one hand a metal basket on which two winged men adored the holy tree, and in the other a fir cone.[381]

Layard suggested that the latter deity, with eagle’s head, was Nisroch, “the word Nisr signifying, in all Semitic languages, an eagle”.[382] This deity is referred to in the Bible: “Sennacherib, king of Assyria, ... was worshipping in the house of Nisroch, his god”.[383] Professor Pinches is certain that Nisroch is Ashur, but considers that the “ni” was attached to “Ashur” (Ashuraku or Ashurachu), as it was to “Marad” (Merodach) to give the reading Ni-Marad = Nimrod. The names of heathen deities were thus made “unrecognizable, and in all probability ridiculous as well.... Pious and orthodox lips could pronounce them without fear of defilement.”[384] At the same time the “Nisr” theory is probable: it may represent another phase of this process. The names of heathen gods were not all treated in like manner by the Hebrew teachers. Abed-nebo, for instance, became Abed-nego, Daniel, i, 7), as Professor Pinches shows.

Seeing that the eagle received prominence in the mythologies of Sumeria and Assyria, as a deity of fertility with solar and atmospheric attributes, it is highly probable that the Ashur symbol, like the Egyptian Horus solar disk, is a winged symbol of life, fertility, and destruction. The idea that it represents the sun in eclipse, with protruding rays, seems rather far-fetched, because eclipses were disasters and indications of divine wrath;[385] it certainly does not explain why the “rays” should only stretch out sideways, like wings, and downward like a tail, why the “rays” should be double, like the double wings of cherubs, bulls, &c, and divided into sections suggesting feathers, or why the disk is surmounted by conventionalized horns, tipped with star-like ring symbols, identical with those depicted in the holy tree. What particular connection the five small rings within the disk were supposed to have with the eclipse of the sun is difficult to discover.

In one of the other symbols in which appears a feather-robed archer, it is significant to find that the arrow he is about to discharge has a head shaped like a trident; it is evidently a lightning symbol.

When Ezekiel prophesied to the Israelitish captives at Tel-abib, “by the river of Chebar” in Chaldea (Kheber, near Nippur), he appears to have utilized Assyrian symbolism. Probably he came into contact in Babylonia with fugitive priests from Assyrian cities.

This great prophet makes interesting references to “four living creatures”, with “four faces”--the face of a man, the face of a lion, the face of an ox, and the face of an eagle; “they had the hands of a man under their wings, ... their wings were joined one to another; ... their wings were stretched upward: two wings of every one were joined one to another.... Their appearance was like burning coals of fire and like the appearance of lamps.... The living creatures ran and returned as the appearance of a flash of lightning.”[386]

Elsewhere, referring to the sisters, Aholah and Aholibah, who had been in Egypt and had adopted unmoral ways of life Ezekiel tells that when Aholibah “doted upon the Assyrians” she “saw men pourtrayed upon the wall, the images of the Chaldeans pourtrayed with vermilion, girded with girdles upon their loins”.[387] Traces of the red colour on the walls of Assyrian temples and palaces have been observed by excavators. The winged gods “like burning coals” were probably painted in vermilion.

Ezekiel makes reference to “ring” and “wheel” symbols. In his vision he saw “one wheel upon the earth by the living creatures, with his four faces. The appearance of the wheels and their work was like unto the colour of beryl; and they four had one likeness; and their appearance and their work was as it were a wheel in the middle of a wheel.... As for their rings, they were so high that they were dreadful; and their rings were full of eyes round about them four. And when the living creatures went, the wheels went by them; and when the living creatures were lifted up from the earth, the wheels were lifted up. Whithersoever the spirit was to go, they went, thither was their spirit to go; and the wheels were lifted up over against them; for the spirit of the living creature was in the wheels....[388] And the likeness of the firmament upon the heads of the living creature was as the colour of terrible crystal, stretched forth over their heads above.... And when they went I heard the noise of their wings, like the noise of great waters, as the voice of the Almighty, the voice of speech, as the noise of an host; when they stood they let down their wings....”[389]

Another description of the cherubs states: “Their whole body, and their backs, and their hands, and their wings, and the wheels, were full of eyes (? stars) round about, even the wheels that they four had. As for the wheels, it was cried unto them in my hearing, O wheel!” --or, according to a marginal rendering, “they were called in my hearing, wheel, or Gilgal,” i.e. move round.... “And the cherubims were lifted up.”[390]

It would appear that the wheel (or hoop, a variant rendering) was a symbol of life, and that the Assyrian feather-robed figure which it enclosed was a god, not of war only, but also of fertility. His trident-headed arrow resembles, as has been suggested, a lightning symbol. Ezekiel’s references are suggestive in this connection. When the cherubs “ran and returned” they had “the appearance of a flash of lightning”, and “the noise of their wings” resembled “the noise of great waters”. Their bodies were “like burning coals of fire”. Fertility gods were associated with fire, lightning, and water. Agni of India, Sandan of Asia Minor, and Melkarth of Phoenicia were highly developed fire gods of fertility. The fire cult was also represented in Sumeria (pp. 49-51).

In the Indian epic, the Mahabharata, the revolving ring or wheel protects the Soma[391] (ambrosia) of the gods, on which their existence depends. The eagle giant Garuda sets forth to steal it. The gods, fully armed, gather round to protect the life-giving drink. Garuda approaches “darkening the worlds by the dust raised by the hurricane of his wings”. The celestials, “overwhelmed by that dust”, swoon away. Garuda afterwards assumes a fiery shape, then looks “like masses of black clouds”, and in the end its body becomes golden and bright “as the rays of the sun”. The Soma is protected by fire, which the bird quenches after “drinking in many rivers” with the numerous mouths it has assumed. Then Garuda finds that right above the Soma is “a wheel of steel, keen edged, and sharp as a razor, revolving incessantly. That fierce instrument, of the lustre of the blazing sun and of terrible form, was devised by the gods for cutting to pieces all robbers of the Soma.” Garuda passes “through the spokes of the wheel”, and has then to contend against “two great snakes of the lustre of blazing fire, of tongues bright as the lightning flash, of great energy, of mouth emitting fire, of blazing eyes”. He slays the snakes.... The gods afterwards recover the stolen Soma.

Garuda becomes the vehicle of the god Vishnu, who carries the discus, another fiery wheel which revolves and returns to the thrower like lightning. “And he (Vishnu) made the bird sit on the flagstaff of his car, saying: ‘Even thus thou shalt stay above me’.”[392]

The Persian god Ahura Mazda hovers above the king in sculptured representations of that high dignitary, enclosed in a winged wheel, or disk, like Ashur, grasping a ring in one hand, the other being lifted up as if blessing those who adore him.

Shamash, the Babylonian sun god; Ishtar, the goddess of heaven; and other Babylonian deities carried rings as the Egyptian gods carried the ankh, the symbol of life. Shamash was also depicted sitting on his throne in a pillar-supported pavilion, in front of which is a sun wheel. The spokes of the wheel are formed by a star symbol and threefold rippling “water rays”.

In Hittite inscriptions there are interesting winged emblems; “the central portion” of one “seems to be composed of two crescents underneath a disk (which is also divided like a crescent). Above the emblem there appear the symbol of sanctity (the divided oval) and the hieroglyph which Professor Sayce interprets as the name of the god Sandes.” In another instance “the centre of the winged emblem may be seen to be a rosette, with a curious spreading object below. Above, two dots follow the name of Sandes, and a human arm bent ‘in adoration’ is by the side....” Professor Garstang is here dealing with sacred places “on rocky points or hilltops, bearing out the suggestion of the sculptures near Boghaz-Keui[393], in which there may be reasonably suspected the surviving traces of mountain cults, or cults of mountain deities, underlying the newer religious symbolism”. Who the deity is it is impossible to say, but “he was identified at some time or other with Sandes”.[394] It would appear, too, that the god may have been “called by a name which was that used also by the priest”. Perhaps the priest king was believed to be an incarnation of the deity.

Sandes or Sandan was identical with Sandon of Tarsus, “the prototype of Attis”,[395] who links with the Babylonian Tammuz. Sandon’s animal symbol was the lion, and he carried the “double axe” symbol of the god of fertility and thunder. As Professor Frazer has shown in The Golden Bough, he links with Hercules and Melkarth.[396]

All the younger gods, who displaced the elder gods as one year displaces another, were deities of fertility, battle, lightning, fire, and the sun; it is possible, therefore, that Ashur was like Merodach, son of Ea, god of the deep, a form of Tammuz in origin. His spirit was in the solar wheel which revolved at times of seasonal change. In Scotland it was believed that on the morning of May Day (Beltaine) the rising sun revolved three times. The younger god was a spring sun god and fire god. Great bonfires were lit to strengthen him, or as a ceremony of riddance; the old year was burned out. Indeed the god himself might be burned (that is, the old god), so that he might renew his youth. Melkarth was burned at Tyre. Hercules burned himself on a mountain top, and his soul ascended to heaven as an eagle.

These fiery rites were evidently not unknown in Babylonia and Assyria. When, according to Biblical narrative, Nebuchadnezzar “made an image of gold” which he set up “in the plain of Dura, in the province of Babylon”, he commanded: “O people, nations, and languages... at the time ye hear the sound of the cornet, flute, harp, sackbut, psaltery, dulcimer, and all kinds of musick... fall down and worship the golden image”. Certain Jews who had been “set over the affairs of the province of Babylonia”, namely, “Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-nego”, refused to adore the idol. They were punished by being thrown into “a burning fiery furnace”, which was heated “seven times more than it was wont to be heated”. They came forth uninjured.[397]

In the Koran it is related that Abraham destroyed the images of Chaldean gods; he “brake them all in pieces except the biggest of them; that they might lay the blame on that”.[398] According to the commentators the Chaldaeans were at the time “abroad in the fields, celebrating a great festival”. To punish the offender Nimrod had a great pyre erected at Cuthah. “Then they bound Abraham, and putting him into an engine, shot him into the midst of the fire, from which he was preserved by the angel Gabriel, who was sent to his assistance.” Eastern Christians were wont to set apart in the Syrian calendar the 25th of January to commemorate Abraham’s escape from Nimrod’s pyre.[399]

It is evident that the Babylonian fire ceremony was observed in the spring season, and that human beings were sacrificed to the sun god. A mock king may have been burned to perpetuate the ancient sacrifice of real kings, who were incarnations of the god.

Isaiah makes reference to the sacrificial burning of kings in Assyria: “For through the voice of the Lord shall the Assyrian be beaten down, which smote with a rod. And in every place where the grounded staff shall pass, which the Lord shall lay upon him, it shall be with tabrets and harps: and in battles of shaking will he fight with it. For Tophet is ordained of old; yea, for the king it is prepared: he hath made it deep and large: the pile thereof is fire and much wood: the breath of the Lord, like a stream of brimstone, doth kindle it.”[400] When Nineveh was about to fall, and with it the Assyrian Empire, the legendary king, Sardanapalus, who was reputed to have founded Tarsus, burned himself, with his wives, concubines, and eunuchs, on a pyre in his palace. Zimri, who reigned over Israel for seven days, “burnt the king’s house over him with fire”[401]. Saul, another fallen king, was burned after death, and his bones were buried “under the oak in Jabesh”.[402] In Europe the oak was associated with gods of fertility and lightning, including Jupiter and Thor. The ceremony of burning Saul is of special interest. Asa, the orthodox king of Judah, was, after death, “laid in the bed which was filled with sweet odours and divers kinds of spices prepared by the apothecaries’ art: and they made a very great burning for him” (2 Chronicles, xvi, 14). Jehoram, the heretic king of Judah, who “walked in the way of the kings of Israel”, died of “an incurable disease. And his people made no burning for him like the burning of his fathers” (2 Chronicles, xxi, 18, 19).

The conclusion suggested by the comparative study of the beliefs of neighbouring peoples, and the evidence afforded by Assyrian sculptures, is that Ashur was a highly developed form of the god of fertility, who was sustained, or aided in his conflicts with demons, by the fires and sacrifices of his worshippers.

It is possible to read too much into his symbols. These are not more complicated and vague than are the symbols on the standing stones of Scotland--the crescent with the “broken” arrow; the trident with the double rings, or wheels, connected by two crescents; the circle with the dot in its centre; the triangle with the dot; the large disk with two small rings on either side crossed by double straight lines; the so-called “mirror”, and so on. Highly developed symbolism may not indicate a process of spiritualization so much, perhaps, as the persistence of magical beliefs and practices. There is really no direct evidence to support the theory that the Assyrian winged disk, or disk “with protruding rays”, was of more spiritual character than the wheel which encloses the feather-robed archer with his trident-shaped arrow.

The various symbols may have represented phases of the god. When the spring fires were lit, and the god “renewed his life like the eagle”, his symbol was possibly the solar wheel or disk with eagle’s wings, which became regarded as a symbol of life. The god brought life and light to the world; he caused the crops to grow; he gave increase; he sustained his worshippers. But he was also the god who slew the demons of darkness and storm. The Hittite winged disk was Sandes or Sandon, the god of lightning, who stood on the back of a bull. As the lightning god was a war god, it was in keeping with his character to find him represented in Assyria as “Ashur the archer” with the bow and lightning arrow. On the disk of the Assyrian standard the lion and the bull appear with “the archer” as symbols of the war god Ashur, but they were also symbols of Ashur the god of fertility.

The life or spirit of the god was in the ring or wheel, as the life of the Egyptian and Indian gods, and of the giants of folk tales, was in “the egg”. The “dot within the circle”, a widespread symbol, may have represented the seed within “the egg” of more than one mythology, or the thorn within the egg of more than one legendary story. It may be that in Assyria, as in India, the crude beliefs and symbols of the masses were spiritualized by the speculative thinkers in the priesthood, but no literary evidence has survived to justify us in placing the Assyrian teachers on the same level as the Brahmans who composed the Upanishads.

Temples were erected to Ashur, but he might be worshipped anywhere, like the Queen of Heaven, who received offerings in the streets of Jerusalem, for “he needed no temple”, as Professor Pinches says. Whether this was because he was a highly developed deity or a product of folk religion it is difficult to decide. One important fact is that the ruling king of Assyria was more closely connected with the worship of Ashur than the king of Babylonia was with the worship of Merodach. This may be because the Assyrian king was regarded as an incarnation of his god, like the Egyptian Pharaoh. Ashur accompanied the monarch on his campaigns: he was their conquering war god. Where the king was, there was Ashur also. No images were made of him, but his symbols were carried aloft, as were the symbols of Indian gods in the great war of the Mahabharata epic.

It would appear that Ashur was sometimes worshipped in the temples of other gods. In an interesting inscription he is associated with the moon god Nannar (Sin) of Haran. Esarhaddon, the Assyrian king, is believed to have been crowned in that city. “The writer”, says Professor Pinches, “is apparently addressing Assur-bani-apli, ‘the great and noble Asnapper’:

“When the father of my king my lord went to Egypt, he was crowned (?) in the ganni of Harran, the temple (lit. ‘Bethel’) of cedar. The god Sin remained over the (sacred) standard, two crowns upon his head, (and) the god Nusku stood beside him. The father of the king my lord entered, (and) he (the priest of Sin) placed (the crown?) upon his head, (saying) thus: ‘Thou shalt go and capture the lands in the midst’. (He we)nt, he captured the land of Egypt. The rest of the lands not submitting (?) to Assur (Ashur) and Sin, the king, the lord of kings, shall capture (them).”[403]

Ashur and Sin are here linked as equals. Associated with them is Nusku, the messenger of the gods, who was given prominence in Assyria. The kings frequently invoked him. As the son of Ea he acted as the messenger between Merodach and the god of the deep. He was also a son of Bel Enlil, and like Anu was guardian or chief of the Igigi, the “host of heaven”. Professor Pinches suggests that he may have been either identical with the Sumerian fire god Gibil, or a brother of the fire god, and an impersonation of the light of fire and sun. In Haran he accompanied the moon god, and may, therefore, have symbolized the light of the moon also. Professor Pinches adds that in one inscription “he is identified with Nirig or En-reshtu” (Nin-Girsu = Tammuz).[404] The Babylonians and Assyrians associated fire and light with moisture and fertility.

The astral phase of the character of Ashur is highly probable. As has been indicated, the Greek rendering of Anshar as “Assoros”, is suggestive in this connection. Jastrow, however, points out that the use of the characters Anshar for Ashur did not obtain until the eighth century B.C. “Linguistically”, he says, “the change of Ashir to Ashur can be accounted for, but not the transformation of An-shar to Ashur or Ashir; so that we must assume the ‘etymology’ of Ashur, proposed by some learned scribe, to be the nature of a play upon the name.”[405] On the other hand, it is possible that what appears arbitrary to us may have been justified in ancient Assyria on perfectly reasonable, or at any rate traditional, grounds. Professor Pinches points out that as a sun god, and “at the same time not Shamash”, Ashur resembled Merodach. “His identification with Merodach, if that was ever accepted, may have been due to the likeness of the word to Asari, one of the deities’ names.”[406] As Asari, Merodach has been compared to the Egyptian Osiris, who, as the Nile god, was Asar-Hapi. Osiris resembles Tammuz and was similarly a corn deity and a ruler of the living and the dead, associated with sun, moon, stars, water, and vegetation. We may consistently connect Ashur with Aushar, “water field”, Anshar, “god of the height”, or “most high”, and with the eponymous King Asshur who went out on the land of Nimrod and “builded Nineveh”, if we regard him as of common origin with Tammuz, Osiris, and Attis--a developed and localized form of the ancient deity of fertility and corn.

Ashur had a spouse who is referred to as Ashuritu, or Beltu, “the lady”. Her name, however, is not given, but it is possible that she was identified with the Ishtar of Nineveh. In the historical texts Ashur, as the royal god, stands alone. Like the Hittite Great Father, he was perhaps regarded as the origin of life. Indeed, it may have been due to the influence of the northern hillmen in the early Assyrian period, that Ashur was developed as a father god--a Baal. When the Hittite inscriptions are read, more light may be thrown on the Ashur problem. Another possible source of cultural influence is Persia. The supreme god Ahura-Mazda (Ormuzd) was, as has been indicated, represented, like Ashur, hovering over the king’s head, enclosed in a winged disk or wheel, and the sacred tree figured in Persian mythology. The early Assyrian kings had non-Semitic and non-Sumerian names. It seems reasonable to assume that the religious culture of the ethnic elements they represented must have contributed to the development of the city god of Asshur.

[355] Genesis, x, 11.

[356] “A number of tablets have been found in Cappadocia of the time of the Second Dynasty of Ur which show marked affinities with Assyria. The divine name Ashir, as in early Assyrian texts, the institution of eponyms and many personal names which occur in Assyria, are so characteristic that we must assume kinship of peoples. But whether they witness to a settlement in Cappadocia from Assyria, or vice versa, is not yet clear.” Ancient Assyria, C.H.W. Johns (Cambridge, 1912), pp. 12-13.

[357] Sumerian Ziku, apparently derived from Zi, the spiritual essence of life, the “self power” of the Universe.

[358] Peri Archon, cxxv.

[359] Religion of Babylonia and Assyria, p. 197 et seq.

[360] Julius Caesar, act iii, scene I.

[361] Isaiah, xiv, 4-14.

[362] Eddubrott, ii.

[363] Religion of the Ancient Egyptians, A. Wiedemann, pp. 289-90.

[364] Ibid., p. 236. Atlas was also believed to be in the west.

[365] Primitive Constellations, vol. ii, p. 184.

[366] Cuneiform Inscriptions of Western Asia, xxx, II.

[367] Isaiah, xiii, 21. For “Satyrs” the Revised Version gives the alternative translation, “or he-goats”.

[368] Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria, p. 120, plate 18 and note.

[369] Satapatha Brahmana, translated by Professor Eggeling, part iv, 1897, p. 371. (Sacred Books of the East.)

[370] Egyptian Myth and Legend, pp. 165 et seq.

[371] Classic Myth and Legend, p. 105. The birds were called “Stymphalides”.

[372] The so-called “shuttle” of Neith may be a thunderbolt. Scotland’s archaic thunder deity is a goddess. The bow and arrows suggest a lightning goddess who was a deity of war because she was a deity of fertility.

[373] Vedic Index, Macdonell & Keith, vol. ii, pp. 125-6, and vol. i, 168-9.

[374] Ezekiel, xxxi, 3-8.

[375] Ezekiel, xxvii, 23, 24.

[376] Isaiah, xxxvii, 11.

[377] Ibid., x, 5, 6.

[378] A winged human figure, carrying in one hand a basket and in another a fir cone.

[379] Layard’s Nineveh (1856), p. 44.

[380] Ibid., p. 309.

[381] The fir cone was offered to Attis and Mithra. Its association with Ashur suggests that the great Assyrian deity resembled the gods of corn and trees and fertility.

[382] Nineveh, p. 47.

[383] Isaiah, xxxvii, 37-8.

[384] The Old Testament in the Light of the Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and Babylonia, pp. 129-30.

[385] An eclipse of the sun in Assyria on June 15, 763 B.C., was followed by an outbreak of civil war.

[386] Ezekiel, i, 4-14.

[387] Ezekiel, xxiii, 1-15.

[388] As the soul of the Egyptian god was in the sun disk or sun egg.

[389] Ezekiel,, i, 15-28.

[390] Ezekiel, x, 11-5.

[391] Also called “Amrita”.

[392] The Mahabharata (Adi Parva), Sections xxxiii-iv.

[393] Another way of spelling the Turkish name which signifies “village of the pass”. The deep “gh” guttural is not usually attempted by English speakers. A common rendering is “Bog-haz’ Kay-ee”, a slight “oo” sound being given to the “a” in “Kay”; the “z” sound is hard and hissing.

[394] The Land of the Hittites, J. Garstang, pp. 178 et seq.

[395] Ibid., p. 173.

[396] Adonis, Attis, Osiris, chaps. v and vi.

[397] Daniel, iii, 1-26.

[398] The story that Abraham hung an axe round the neck of Baal after destroying the other idols is of Jewish origin.

[399] The Koran, George Sale, pp. 245-6.

[400] Isaiah, xxx, 31-3. See also for Tophet customs 2 Kings, xxiii, 10; Jeremiah, vii, 31, 32 and xix, 5-12.

[401] 1 Kings, xvi, 18.

[402] 1 Samuel, xxxi, 12, 13 and 1 Chronicles, x, 11, 12.

[403] The Old Testament in the Light of the Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and Babylonia, pp. 201-2.

[404] Babylonian and Assyrian Religion, pp. 57-8.

[405] Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria, p. 121.

[406] Babylonian and Assyrian Religion, p. 86.