EIGHT

EIGHT

EIGHT

EIGHT

When the New York City Interborough Rapid Transit subway, commonly known as the IRT, was officially opened on October 27, 1904, it changed the nature of the nation’s largest metropolis and was accompanied by one of the greatest celebrations the city had ever known. But few of those who engaged in that celebration were aware of the fact that the IRT was not the first subway built in New York, and most people today don’t know about it. The amazing story of the construction of the city’s first underground railway has been largely lost to history. At its heart is the tale of one man’s determination to save the city he loved and to revolutionize the way people moved about within it. It is a story made even more remarkable by the fact that the subway he constructed was built almost entirely in secret.

By the time this secret subway was built, New York had become the envy of other metropolises around the world. As early as 1842, the editor of the daily New York Aurora, a twenty-two-year-old with a future named Walt Whitman, wrote, “Who does not know that our city is the great place of the Western Continent, the heart, the brain, the focus, the main spring, the pinnacle, the extremity, the no more beyond of the New World.”

AN 1868 LITHOGRAPH of a proposed rail arcade—an elevated railroad—was offered as one solution to the overcrowding in New York City’s streets.

AN 1868 LITHOGRAPH of a proposed rail arcade—an elevated railroad—was offered as one solution to the overcrowding in New York City’s streets.

By the 1860s, New York had become a commercial, financial, and industrial giant, home to more than 800,000 people. Thousands of others poured into the city each year to take advantage of the growing metropolis’s marvelous restaurants, department stores and shops, music halls, and theaters. Nowhere in the nation were there more libraries, museums, or other cultural institutions. It was, in many ways, indeed what young Walt Whitman claimed it to be.

But New York also had a tremendous problem. Its streets were so congested with traffic that the city was coming to a standstill. Every day, hundreds of horse-drawn, buslike vehicles called omnibuses clogged the streets, a situation made worse by the way their drivers raced recklessly from one side of the street to the other, competing for passengers. It was not only a dangerous situation, but a frustrating one as well. “You cannot accomplish anything in the way of business without devoting a whole day to it,” wrote author Mark Twain. “You cannot ride [to your destination] unless you are willing to go in a packed omnibus that labors, and plunges, and struggles along at the rate of three miles in four hours and a half.”

A CHAOTIC NEW YORK CITY street ca. 1870.

A CHAOTIC NEW YORK CITY street ca. 1870.

Adding to the mayhem were hundreds of horse-drawn delivery wagons and private carriages. The health hazards caused by the traffic were not slight. Several New York doctors speculated that many of the nervous disorders suffered by the city’s residents were caused by the constant clatter of horse hooves and wooden wagon wheels. What was not speculative was the very real danger caused by the tons of manure that the animals dropped on the streets every day. Obviously a solution was needed, a fact stated forcefully on October 8, 1864, by the New York Herald, when it described the experience of riding in city public transportation:

The driver swears at the passengers and the passengers harangue the driver through the strap-hole—a position in which even Demosthenes could not be eloquent. Respectable clergymen in white chokers are obliged to listen to loud oaths. Ladies are disgusted, frightened and insulted. Children are alarmed and lift up their voices and weep. . . . Thus the omnibus rolls along, a perfect Bedlam on wheels. . . . The cars are quieter than the omnibuses, but much more crowded. People are packed into them like sardines in a box, with perspiration for oil. The seats being more than filled, the passengers are placed in rows down the middle, where they hang on by the straps, like smoked hams in a corner grocery. To enter or exit is exceedingly difficult. Silks and broadcloth are ruined in the attempt. As in the omnibuses pickpockets take advantage of the confusion to ply their vocation. . . . The foul, close, heated air is poisonous. A healthy person cannot ride a dozen blocks without a headache. . . . it must be evident to everybody that neither the cars nor the stages supply accommodations enough for the public, and that such accommodations as they do supply are not of the right sort. Both the cars and the omnibuses might be very comfortable and convenient if they were better managed, but something more is needed to supply the popular and increasing demand for city conveyances.

It was a statement with which Alfred Ely Beach could not have agreed more. No one loved New York more than he, but every day as he looked down upon Broadway from his office he shook his head in dismay. Something had to be done to solve the city’s horrific traffic problems. Someone had to come up with an idea for an efficient transit system. Beach was confident enough to believe that he might just be the person to do it.

BEACH WAS ONLY THIRTY-NINE IN OCTOBER 1864, but he had already led a remarkable life. In July 1846, thanks to money he received from his wealthy father, he and a former classmate, Orson D. Munn, purchased a small weekly journal called Scientific American.

ALFRED ELY BEACH.

ALFRED ELY BEACH.

Although he was only nineteen years old, Beach had ambitious plans for the publication. Aware that the nation was in the midst of an unprecedented technological and scientific revolution, he was determined to make the magazine the printed voice of the remarkable changes that were taking place. The fact that Beach increased the magazine’s focus on descriptions of new inventions and newly applied-for patents ensured the success of the magazine and led to a whole new business avenue for the young entrepreneur. As the magazine became increasingly popular, inventors and tinkerers began appearing at Scientific American’s office, seeking advice about obtaining patents for their creations. Sensing a real opportunity, Beach and Munn established Munn and Co., also known as the Scientific American Patent Agency, a company devoted both to helping inventors compose their patent applications as effectively as possible and to monitoring the progress of each application once it was being processed by the U.S. Patent Office.

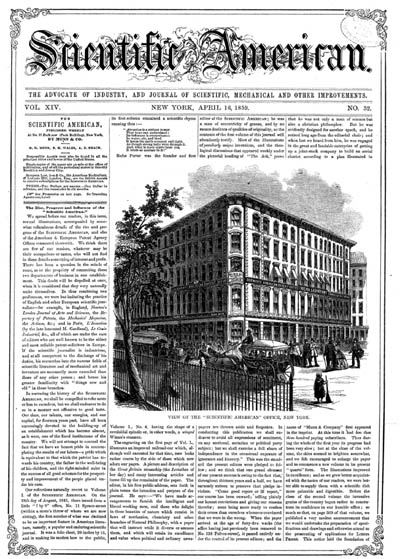

THE FRONT PAGE of volume 14 of Scientific American, April 16, 1859, depicts an illustration of the Scientific American Patent Agency building.

THE FRONT PAGE of volume 14 of Scientific American, April 16, 1859, depicts an illustration of the Scientific American Patent Agency building.

It was a unique business, and it became so successful that by the late 1850s more than three thousand patents were being filed by Beach’s company each year. Ten years later, more than a third of all the patents awarded in the United States had been submitted by the Scientific American Patent Agency, which, by this time, had opened branches in other locations, including one in Washington, D.C., directly across from the U.S. Patent Office.

It is not surprising that Beach became an inventor himself, given that he was constantly surrounded by inventors, their creations, and their patent applications. Beach’s agency filed patents for his own inventions, including a patent for the world’s first cable railway system and another for a machine by which blind persons could create printed messages. Although Beach never followed up on these inventions, the cable systems later built in San Francisco and Chicago were based on his design, and his invention of a printing machine for the blind led directly to the development of the modern typewriter. And that was not all. He had become fascinated with the power of pneumatic tubes, particularly what he saw as their potential for transportation.

Still, with all that he had achieved, Beach was a dissatisfied man. There had to be a way, he believed, to solve New York’s disastrous traffic problem. His first idea was to build elevated railways above the city, thus relieving the congested streets below. But as he thought through this idea more fully, he backed away from it. Elevated railways would make the streets below them dark and uninviting. They would be as noisy as the omnibuses that clogged the streets. Most important, they would not be able to carry enough people to provide a real solution.

No, he told himself, the answer lay elsewhere. It had to be something far more dramatic, far more effective. And increasingly he became convinced that he had the solution. It had to be a subway, an underground system that could move people away from all the congestion, noise, and health hazards. Subways weren’t a completely new concept. The London subway, built in 1863, had already transported millions of people. But that system, based on locomotives pulling the cars, had proved terribly problematic. The locomotives gave off noxious fumes that had already made a number of people seriously ill. In addition, locomotives, which burned a low grade of coal, also gave off showers of sparks, and more than one passenger had had his clothing set afire. If a subway was the answer, then there had to be a much better way to propel the cars. And it had to be totally safe and totally clean.

He found his answer in work he had already done. In his fascination with pneumatics, Beach had spent considerable time reading about pneumatic railways that had been built in England to carry mail and small packages. He had been particularly impressed with the accomplishments of British engineer Thomas Rammell, who, in 1863, had constructed an underground pneumatic tube through which mail had been successfully transported. Sadly for Rammell, his system—which ran in Camden, London, between an arrivals parcel office and a district post office several miles away—proved too costly to be profitable and was eventually abandoned. But what impressed Beach the most about Rammell’s primitive operation was not that it worked, but that several people had actually snuck aboard Rammell’s cars and had safely made the journey, propelled by air through the underground tube.

He had become even more intrigued when he had read about how Rammell had built a small aboveground tube designed to carry passengers for about a quarter of a mile between two of the gates at London’s great Crystal Palace Exhibition. Particularly interesting was a report on Rammell’s tube that had appeared in Mechanics Magazine in 1864. “The entire distance [of the tunnel], six hundred yards,” the publication proclaimed, “is transversed in about 50 seconds . . . The motion is of course easy and pleasant, and the ventilation ample, without being in any way excessive. . . . We feel tolerably certain that the day is not very distant when metropolitan railway traffic can be conducted on this principle with so much success, as far as popular likeing goes, that the locomotive will be unknown on the underground lines.”

If there was anyone with whom that prediction would resonate, it was Beach. But he also knew that it was a prophecy that lacked details of how such a system could be made practical. First of all, there was the not so incidental challenge of building a tunnel, not under the open grounds of Crystal Palace Park, but under one of the busiest streets in the world. And Beach realized that another problem would have to be faced. How do you motivate city dwellers to descend into an ill-lit, spooky underground world to get on trains?

But the more he thought about it, the more he became convinced that a pneumatic subway was the only answer. One thing he knew for certain. Even in operating the first-stage experimental short line he was intending to build, he would need the biggest fan he could obtain to propel his cars with air and the largest steam engine available to most effectively power the fan.

After weeks of investigation, he discovered a company in Indiana that made a machine that was used in ventilating mines. In describing the machine (which he called an æolor after the Greek god of wind, Æolus), Beach later wrote, “[It] is by far the largest machine of the kind ever made. . . . [It] weighs fifty tons, or rather more than a common locomotive engine. The æolor is to the pneumatic railway what the locomotive is to the ordinary steam railroad. The locomotive supplies the power to draw the car; the æolor gives motive force to the air by which the pneumatic car is moved. The æolor is capable of discharging over one hundred thousand cubic feet of air per minute, a volume equal in bulk to the contents of three ordinary three story dwelling houses.” No wonder that workers in the factory that made the machine gave it the nickname the “Western Tornado.”

With his giant “blower,” Beach now believed he had the machinery to power his unique subway. But he was well aware that in order to impress the New York legislature, the press, and the public, he would have to go a giant step further. He had to attract riders by making the subway as appealing and comfortable as possible. Beach began by designing a subway car equipped with one of the new marvels of the age, zircon lights, which burned clearer and far brighter than ordinary gaslights. His design called for the car to be fitted with the richest, most comfortable upholstery available and a sturdy pneumatically sealing airtight door. Then he was struck with a truly inspired idea.

Realizing that his subway needed a waiting room, and that the waiting room was where passengers would form their first vital impressions of the subway, Beach laid out plans for a 120-by-14-foot room that would be as elegant as the finest room in the most expensive New York hotel. Its features included a crystal chandelier, fine paintings, a grand piano, and a huge fountain filled with goldfish—all beneath the city. Nothing like it had even been imagined.

But would it all work? Beach was absolutely convinced that it would. In fact, now that he was convinced he had worked out the details, it was, to him, a most uncomplicated idea. What could be simpler, he later explained, than a system by which the blower propelled his car from one end of his tunnel to the other “like a sail-boat before the wind?” What could be more easily imagined than that the blower would then reverse the airflow, sucking the car back to where it had begun “like soda through a straw?” In what would become a phrase he would use over and over again, Beach would declare, “A tube, a car, a revolving fan. Little more is required.”

It was an understatement, of course. Much more was, in fact, required. First he had to publicly demonstrate that his idea would work. Then he had to convince the New York legislature to give him a license to build an experimental line. And should all that be accomplished, there was the small matter of building a tunnel under New York’s busiest street.

BEACH GOT HIS OPPORTUNITY TO demonstrate the pneumatic tube transport when he learned that the annual highly attended American Institute Fair was to be held on September 17, 1867, in New York. Here was his opportunity to introduce America to the wonders of pneumatic transportation, his opportunity to get the license he needed to make his vision a reality. Over the weeks leading to the fair, he had workers build a 107-foot-long, 16-foot-wide tube. Then he built a car designed to carry ten passengers through this demonstration “tunnel.” He provided pneumatic power for the cars by acquiring a fan powerful enough to serve his purposes. Finally, he had the tube hung by huge cables suspended from the armory’s ceiling. For the next six weeks, more than 170,000 amazed and delighted men, women, and children rode in Beach’s cars. By the time the fair ended, both the public and press agreed that the “subway” was the event’s most spectacular feature. Most important to Beach were the articles in the press that confirmed his belief that the subway was not a mere novelty but the answer to the city’s transportation nightmare. The New York Times of September 16, 1871, extolled the invention:

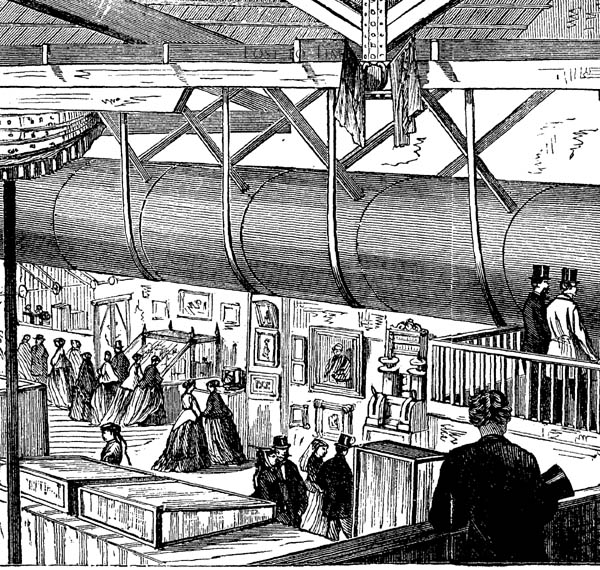

TOURISTS EXPERIENCE THE Pneumatic Passenger Railway at the American Institute Fair in New York, 1867.

TOURISTS EXPERIENCE THE Pneumatic Passenger Railway at the American Institute Fair in New York, 1867.

It is . . . estimated that passengers by a through city tube could be carried from City Hall to Madison Square in five minutes, to Harlem and Manhattanville in fourteen minutes, and by sub-river to Jersey City or Hoboken in five minutes, and to the City Hall, Brooklyn in two minutes. . . .

Leaving to the imaginations of our accomplished readers the pleasant labor of converting, with all the material here afforded them, our confused and crowded city, with its no less crowded water boundaries, into a terrestrial paradise, where easy locomotion on land, on water, beneath them both, or in the air, can be enjoyed at will, we close this article, hoping, with them, that out of this great field of promise we may some day soon pluck flowers of comfort.

Many of the newspaper reports noted that Beach had not only built a tube for carrying passengers but had also, as part of his demonstration of the potential of pneumatic transportation, hung a smaller companion tube through which letters and packages were transported. When the fair finally ended, Alfred Beach’s triumph was complete. Almost without hesitation the exposition’s officials awarded him their two top prizes—one for his pneumatic passenger railway, the other for what he called his Postal Dispatch.

It was, of course, a great victory. But Beach knew all too well that many obstacles still lay ahead. He had to dig an enormous tunnel. And even before he could begin that daunting project, he had to obtain a charter from both city and state officials. And he was cognizant of the fact that in New York City, this meant getting approval from a man who not only controlled the city, but also may well have been the most corrupt public official that New York or any other American city had ever witnessed.

Standing six feet tall and weighing more than three hundred pounds, William Marcy “Boss” Tweed stood out in every crowd. A man of enormous appetites, his main desire was for money. Tweed entered New York politics as a city alderman in 1852. From that time on, this son of a Scotch-Irish chair maker pursued positions of increasing power as a means to wealth. At one time or another he was a U.S. congressman (1853–55), New York school commissioner (1856–57), member of the board of supervisors for New York County (1858), deputy street commissioner (1861–70), state senator (1867 and 1869), and commissioner of the Department of Public Works (1870). Every one of this staggering array of positions provided Tweed the opportunity to demand enormous bribes and to elicit huge payments for services he never performed. As head of a Democratic political machine in New York known as Tammany Hall, he was able to surround himself with men as dishonest as he was. Their crowning achievement was the way they managed to artificially inflate the cost of the construction of what was formally named the New York County Courthouse, but what came to be commonly called Tweed Courthouse. The building, which in 1858 was originally budgeted at  250,000, eventually cost taxpayers what has been estimated to be as much as

250,000, eventually cost taxpayers what has been estimated to be as much as  12 million—a good portion of which went into Tweed’s pockets.

12 million—a good portion of which went into Tweed’s pockets.

Some historians have estimated that, expressed in today’s currency, Tweed stole between  1.5 billion and

1.5 billion and  8 billion, making it no surprise that he was one of the wealthiest men in America. As Beach prepared to apply for his charter, Tweed’s holdings included several homes, including a New York City mansion and a large Connecticut country estate, two steam yachts, a private railway car, one of the city’s largest printing houses, and one of its most lavish hotels. Among the possessions for which he was best known was the enormous diamond pin without which he was never seen, an ornament that, according to one of his cronies, he wore “like a planet on his shirt front.”

8 billion, making it no surprise that he was one of the wealthiest men in America. As Beach prepared to apply for his charter, Tweed’s holdings included several homes, including a New York City mansion and a large Connecticut country estate, two steam yachts, a private railway car, one of the city’s largest printing houses, and one of its most lavish hotels. Among the possessions for which he was best known was the enormous diamond pin without which he was never seen, an ornament that, according to one of his cronies, he wore “like a planet on his shirt front.”

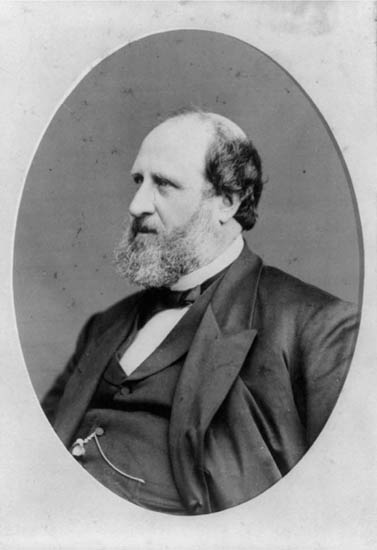

AN UNDATED PHOTOGRAPH of William Marcy “Boss” Tweed.

AN UNDATED PHOTOGRAPH of William Marcy “Boss” Tweed.

Beach was well aware of both Tweed’s power and his character. What troubled him most was the fact that the omnibus and horse-car companies were among the businesses that kicked back money to Tweed. Tweed, he realized, would never approve of a transportation system that might well put these companies out of business unless he was paid a record bribe, probably a large percentage of whatever profits the subway earned. This was something that Beach could not abide. He would have to come up with a plan every bit as creative as the one that had taken his dream of a subway this far.

He came up with a bold idea. Since Tweed was certain to block any plan to build a subway for carrying passengers, he would apply for a charter for the construction of an underground railway for the sole purpose of delivering mail and parcels. Once he secured his charter, he would build a passenger subway, an underground system so efficient, so safe, so comfortable, and so responsive to the city’s greatest need that once it was revealed, even the mighty Boss Tweed would not be able to prevent the legislature from granting his ultimate goal: a charter to extend the subway throughout New York City.

His application to the legislature asking for permission to build two small mail delivery underground tubes was quickly approved. Even Tweed saw no threat to his interests in a mail delivery system. Once the license was granted, however, Beach put the second part of his plan in motion, asking permission to build a larger single tube to enclose the two smaller ones, which he claimed would make his mail delivery operation more efficient. This application was approved in May 1869, with Tweed seeing no reason to oppose it.

Now came the biggest challenge of all: not only building a subway that would be so impressive that officials would overlook his deception, but also building it without anyone finding out that it was really a passenger system until it was completed. The nation’s first subway was about to be built in secret.

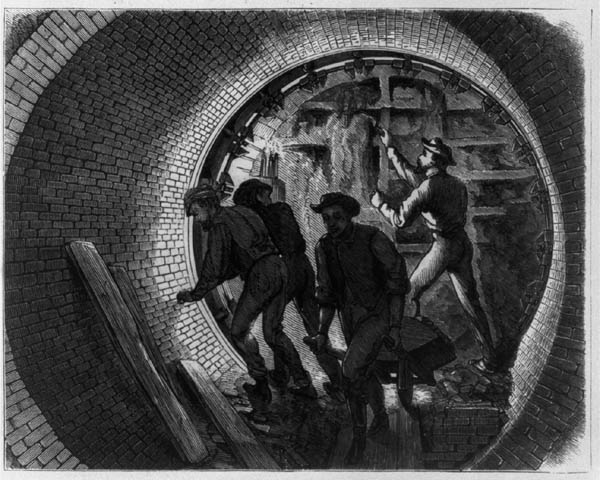

THIS ILLUSTRATION OF ENGINNERS working at night on Beach’s tunnel accompanied an article about the subway in the February 19, 1870, issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.

THIS ILLUSTRATION OF ENGINNERS working at night on Beach’s tunnel accompanied an article about the subway in the February 19, 1870, issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.

LIKE EVERYTHING ELSE WITH WHICH he had been involved, Beach had planned well. His first step, back in December 1868, had been to rent one of the largest department stores on Broadway. The building had not one but two large basement levels. It fit Beach’s scheme perfectly. His tunnel would be dug only at night, when there would be much less traffic overhead to detect what might be going on underneath. As they dug the tunnel, the workmen would pile the dirt in the basements. Then in the darkest hours of the morning, the dirt would be carted away in wagons with muffled wheels and dumped in New York’s East River.

It was an inspired plan, but the greatest challenge of actually digging the tunnel remained. Long before he had applied for his charter, Beach had begun to address the problem. First, improving upon a design that had its origins in 1818 and one that was used by English engineer Marc Isambard Brumel in building the Thames tunnel in 1825, Beach built his own tunneling machine. He called it a hydraulic shield. Open at both ends and cylindrical in shape, it looked like an open-ended barrel. A hand pump within the machine exerted a pressure of some 126 tons, which kept the device stable while moving it forward, allowing the series of rams at the front to dig eight feet of the tunnel each night. Beach saw to it that as each portion of the tunnel was dug, workmen, following the shield, bricked the walls of the portion that had been completed.

A FRANK LESLIE’S ILLUSTRATION of workmen advancing the shield and bricking the tunnel walls.

A FRANK LESLIE’S ILLUSTRATION of workmen advancing the shield and bricking the tunnel walls.

For a man who had never seen a tunnel dug, let alone staked his dream on building one successfully, Beach proved masterful in overseeing many aspects of its construction. But he was also wise enough to realize that he needed expert help as well. Fortunately, he was able to hire the perfect person to serve as his chief engineer: Joseph Dixon, the Englishman who had overseen the building of the tunnel for the London subway.

Together, the two men, along with Beach’s son Frederick, who served as foreman of the digging crews, made certain that progress was made each night. All three were certainly cognizant of how perilous the work was for all those involved. They were digging twenty-one feet below the surface, and even though traffic on Broadway at night was far lighter than during the daytime, Beach must have been constantly concerned that a portion of the street would be weakened by the digging and that a rider on horseback would fall through to the tunnel below, causing bodily harm and exposing the secret project to the outside world.

Amazingly, night after night the project moved on without incident, until it suddenly came to a standstill as workmen encountered a stone wall blocking their path. The vexing question for Beach was whether or not the wall could be removed without causing the street above to collapse, which would literally bring the project to a crashing and, in all probability, tragic halt. But, with Beach directing the removal stone by stone, the structure, which was later revealed to be the wall of an old Dutch fort, was successfully taken down.

By the end of the first week of January 1870, the subway was almost completed. But then the unexpected happened. Somehow, a reporter from the New York Herald found out what was really going on underneath Broadway, went through the department store, descended into the basement, and saw what was taking place. Beach was disappointed at having his secret uncovered so near to the end of the project, but he had to admit that it was remarkable that the project had not been discovered before then. When both the Herald and New York Times published stories describing what was being built below Broadway, he knew what he had to do next.

First, he needed to make sure that everything involving the tunnel, the cars, and the waiting room was as perfect as he could hurriedly make them. Then he needed to hold a lavish reception for city and state officials, showing off what had been accomplished. Then he would open the subway to the public. But before all that could be completed, he needed to buy himself some time, so he had Dixon write a letter to all the newspapers explaining the relatively brief delay. The letter was published in the January 8 edition, and stated in part:

Our original intention was to construct the entire line of tunnel from Warren to Cedar-street, before opening it for inspection, but we have concluded to yield to the strong desire manifested by the Press for an earlier examination. We have, therefore stopped work on the tunnel, and are now fitting up the blowing machinery, engnes [sic], boilers, waiting rooms, &c, with a view of inviting public inspection. . . . Our tunnel commences at the southwest corner of Broadway and Warren-street, curving out to the centre of Broadway and continuing down a little below Murray-street. . . . The top of the tunnel comes within twelve feet of the pavement, so that the walls of adjoining buildings can in no way be affected. We should have preferred to keep silent until our work could speak for us; as it is we beg the Press and public to have a little patience, and in three or four weeks at furthest we will cheerfully afford them an opportunity of inspecting our premises and forming their own judgment as to its merits.

On February 26, Beach held his reception for the region’s dignitaries and the press. It caused a sensation. Every newspaper featured the story on its front page. “PROPOSED UNDERGROUND RAILROAD—A FASHIONABLE RECEPTION HELD IN THE BOWELS OF THE EARTH—THE GREAT BORE EXPLORED,” read the headline in the Herald. Other newspapers focused on what they viewed as an extraordinary accomplishment. “The problem of tunneling Broadway has been solved,” exclaimed the Evening Mail. “There is no mistake about it . . . the work has been pushed vigorously on by competent workmen, under a thoroughly competent superintendent, whose name is Dixon. May his shadow increase for evermore.” It was only the beginning of the praise heaped upon Beach and his subway. “Different papers [will] give different account of the enterprise,” the Sunday Mercury wrote, “but the opening yesterday must have convinced them all of the power of human imagination.” “This means the end of street dust of which uptown residents get not only their fill, but more than their fill, so that it runs over and collects on their hair, their beards, their eyebrows and floats in their dress like a vapor on a frosty morning,” exclaimed Scientific American. “Such discomforts will never be found in the tunnel.”

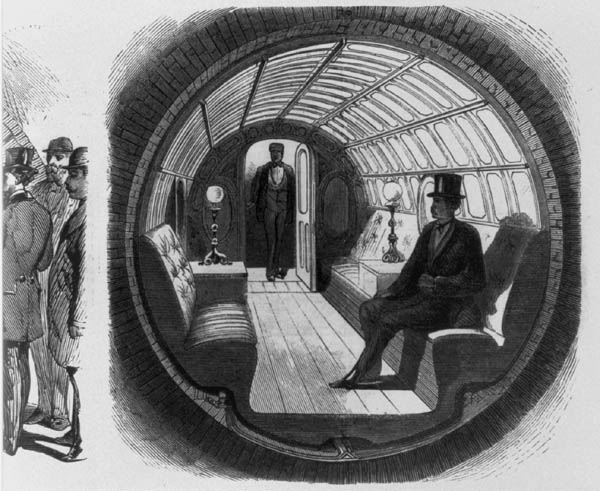

TRAVELING UNDERGROUND in comfort; from the Frank Leslie’s article.

TRAVELING UNDERGROUND in comfort; from the Frank Leslie’s article.

It was praise that exceeded Beach’s hopes. Immediately he announced that on March 1 the subway would be open to the public and that for twenty-five cents, a passenger could experience the joy of being quietly and comfortably transported in a car propelled by air. By this time, each New York newspaper seemed to be trying to outdo its rivals in heaping praise on what had been revealed. “Such as expected to find a dismal cavernous retreat under Broadway,” exclaimed the New York Times, “opened their eyes at the elegant reception room, the light, airy tunnel and the general appearance of taste and comfort in all the apartments, and those who expected to pick out some scientific flaw in the project, were silenced by the completeness of the machinery, the solidity of the work, and the safety of the running apparatus.”

High praise indeed, topped only perhaps by accounts from those members of the public who were among the first to ride the pneumatic railway. “We took our seats in the pretty car, the gayest company of twenty that ever entered a vehicle,” a passenger later wrote.

The conductor touched a telegraph wire on the wall of the tunnel; and before we knew it, so gentle was the start, we were in motion, moving from Warren street down Broadway. In a few moments the conductor opened the door and called out “Murray street!” with a business-like air that made us all shout with laughter. The car came to rest in the gentlest possible style, and immediately began to move back again to Warren Street, where it had no sooner arrived, than in the same gentle and mysterious manner it moved back again to Murray street; and thus it continued to go back and forth for, I should think, twenty minutes, or until we had all ridden as long as we desired. No visible agency gave motion to the car, and the only way that we upon the inside could tell that we were being moved by atmospheric pressure was by holding our hands against the ventilators over the doors. When these were opened, strong currents of pure air came into the car. We could also feel the air-current pressing inward at the bottom of the door. I need hardly say that the ventilation of the pneumatic car is very perfect and agreeable, presenting a strong contrast to the foul atmosphere of [omnibuses and horsecars]. Our atmospheric ride was most delightful, and our party left the car satisfied by actual experience that the pneumatic system of traveling is one of the greatest improvements of the day.

Among the most glowing of the reports were those that hinted of things that even Beach would have declared to be impossible. “So the world goes on,” stated Helen Weeks in the February 1871 issue of Youth’s Companion, “doing more and more wonderful things every day and who knows but that before you . . . readers are old men and women, you and I may go down [into the subway] and in a twinkling find ourselves in England? Who knows?”

Fanciful of course, but to Beach the reality of his overwhelming success meant that the time had come to push for a charter allowing him to extend his subway throughout New York. “We propose to operate a subway all the way to Central Park, about five miles in all,” he stated. “When it’s finished we should be able to carry 20,000 passengers a day at speeds up to a mile a minute.” In her article, Weeks noted “The days of dusty horsecars and rumbling omnibuses are almost at an end. Snow and dust, heat and cold find no kingdom [in the pneumatic subway]. Warm in winter and cool in summer. . . . The weary man or woman who [now] spends hours daily getting to and from business may, when that joyful day of a completed underground comes, allow five minutes for going five miles.”

Five minutes in five miles—what an incredible prospect, so much so that even the strictest legislators were ready to overlook the fact that by building a passenger system rather than a mail delivery system Beach had certainly deceived them. But there was one man who was not willing to either overlook or forgive. As acclaim for the subway mounted, so too did Boss Tweed’s anger. His Tammany Hall cronies had never seen him so furious. The master of the art of deception had been hoodwinked. A passenger system, not a mail system, had been constructed under buildings across the street from City Hall, where Tweed spent so much of his time. Worst of all, as far as he was concerned, not a dime had passed into his pockets.

Despite Tweed’s outrage, Beach was confident that the legislature would enthusiastically grant his charter. He was right. His application for the extension of the subway was overwhelmingly approved. But he had underestimated Boss Tweed’s reach. Once the legislature had granted the charter, the only thing that could revoke it was a veto by New York’s governor, John T. Hoffman. And, as Beach should have realized, Hoffman was controlled by Tweed. Not only did Hoffman veto the legislature’s action, he gave his approval to another bill that had been submitted by none other than Tweed.

Known as the Viaduct Plan, Tweed’s proposal called for the construction of several elevated railways at a cost of more than  80 million. Unlike the subway extension proposal, which Beach had promised to subsidize through money he would raise from private investors, Tweed’s plan called for the elevated railway to be built at taxpayers’ expense, which provided the Boss yet another way to steal millions of dollars.

80 million. Unlike the subway extension proposal, which Beach had promised to subsidize through money he would raise from private investors, Tweed’s plan called for the elevated railway to be built at taxpayers’ expense, which provided the Boss yet another way to steal millions of dollars.

Aware of what Tweed was attempting to do, the legislature met in special session in an attempt to override Hoffman’s veto. But to Beach’s shock and dismay, their vote fell short. After all the acclaim, after he had come so close to having his dream become a reality, Beach was being denied. Still he refused to give up. Mounting a direct appeal to the press and the public, he wrote, “It is only through an underground railway that rapid transit can be realized in New York. The elevated road is inevitably an obstruction, in whatever street it is built, for it is simply an immense bridge, which no one wants before his doors. On the other hand the underground railway is entirely out of sight and disturbs no one.”

It was just one of scores of statements that Beach planted in the press. But as months wore on and as thousands of people continued to ride his short subway with joy, even he became discouraged. He could not get the legislature to make another attempt to override the governor’s veto. Then yet another unexpected development took place.

IN JULY 1871, AN OUTRAGED AND DISSATISFIED New York County bookkeeper appeared at the New York Times downtown offices. In his arms he carried a huge stack of county records. The documents, he claimed, provided the first concrete proof of the hundreds of bribes and kickbacks that Tweed had received over the years. Soon, other records that were produced provided proof of the millions of dollars that had been stolen during the construction of the new courthouse.

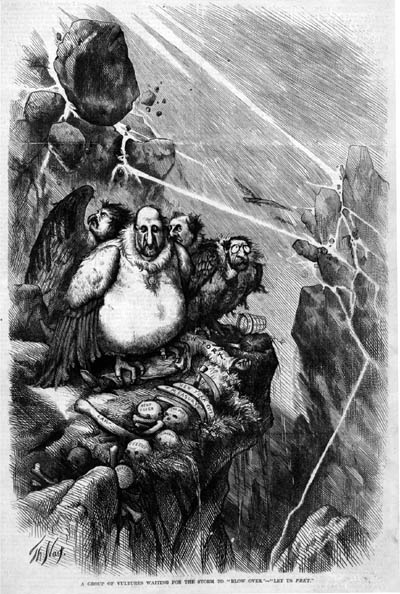

TWEED AND HIS TAMMANY HALL CRONIES are depicted as a group of vultures waiting for the storm to “Blow Over” in this Thomas Nast cartoon from September 23, 1871.

TWEED AND HIS TAMMANY HALL CRONIES are depicted as a group of vultures waiting for the storm to “Blow Over” in this Thomas Nast cartoon from September 23, 1871.

The continuing series of New York Times articles that followed shocked even the most staid New Yorkers. Among them was a Harper’s Weekly artist named Thomas Nast, who, when only twenty-four, had become the nation’s leading cartoonist. Now Nast mounted his own anti-Tweed campaign, lambasting him in scores of widely viewed cartoons, calling for Tweed and his Tammany Hall villains to be brought to justice.

For his part, Tweed had been caught by surprise and taken aback by the Times’s revelations. But he was even more concerned with Nast’s depictions. Arranging a meeting with Harper’s Weekly’s editor, he reportedly shouted, “I don’t care a straw for your newspaper articles; my constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures!”

He was right, and soon the combination of the Times articles and Nast’s cartoons had an effect that went beyond outraging the public. Other New York newspapers, which had for so long been afraid to challenge Tweed’s influence, began printing their own exposés of his criminal acts. Ironically they were joined by a host of newly emboldened city and state officials, long angry with Tweed for not having included them in his payoffs.

Finally, on October 27, 1871, the hitherto indestructible Boss Tweed was arrested. So complex was the case against him that it took fifteen months before he was brought to trial. To the dismay of his prosecutors, the first attempt to convict him ended in a mistrial, but he was tried again in November 1873. This time he was found guilty of fraud and corruption and given a twelve-year sentence.

Tweed’s lawyers, however, had another card to play. Filing an appeal to a higher court on the grounds that even though their client had been tried for multiple offenses he could only be legally sentenced for the punishment applicable to just one of the crimes, they succeeded in getting Tweed’s sentence reduced to just one year.

The story was still far from over. Upon his release from prison, Tweed was arrested again on civil charges and placed back in prison until he could post bail of  3 million. When it originally appeared that he would be arrested, Tweed had responded to reports that, given his influence, he was bound to try to escape by stating: “Now is it likely I’m going to run away? Ain’t my wife, my children’s children, and everything and every interest I have in the world here? What would I gain by running away?”

3 million. When it originally appeared that he would be arrested, Tweed had responded to reports that, given his influence, he was bound to try to escape by stating: “Now is it likely I’m going to run away? Ain’t my wife, my children’s children, and everything and every interest I have in the world here? What would I gain by running away?”

But as he often did, Tweed had lied. During his second incarceration, in a prime example of the influence he still had, he had been allowed to pay a visit to his family. While there, on December 4, 1875, he simply walked out a back door and escaped. He fled to Cuba, then boarded a ship and headed for Spain. What he didn’t know was that the government had discovered his eventual destination. When his ship put into a Spanish port, he was arrested, put on a U.S. naval vessel, brought back to America, and imprisoned once again.

Totally deflated and aware that, in exchange for lighter sentences, some of his closest Tammany Hall associates were about to testify against him, Tweed fell seriously ill. The end came on April 12, 1878, when the man who had spent most of his life surrounded by sycophants and curious onlookers died alone in a dingy prison cell.

For Beach, the demise of his greatest nemesis seemed to signal a complete reversal in his fortunes. In early 1873, the legislature, free of Tweed’s influence, once again voted to give Beach his extension charter. And a new governor quickly signed the measure.

But the subway was not to be. In late 1873 the United States, as a result of overspeculation in the railroads and the financial markets, was experiencing the beginning of the worst economic depression it had ever experienced—one that would last six years. Many of those who had promised to invest in Beach’s enterprise were among the hardest hit. Faced with financial disaster, the New York state and local governments found that supporting a subway system was far down on their list of priorities. Even Beach had to admit that his dream had vanished.

It would be more than a quarter century before New York City would get a subway—not through the vision of a man like Beach or the determination of a group of city officials, but, ironically, through an act of nature.

March 10, 1888, was one of the warmest and most beautiful early spring days that veteran New Yorkers could remember. But the next day was something else entirely. By the time most citizens arose, a howling blizzard was under way, threatening to bury the city in snow. Still, thousands of hardy New Yorkers went to work.

It was a gigantic mistake. By noon, as the snow continued to mount, thousands tried to make their way home. Fallen live electrical wires posed a deadly danger. Signs, tree limbs, and other objects flew uncontrollably through the air, striking and killing or severely injuring scores of others. In one of the most dramatic and dangerous events of the disaster, thousands of passengers attempting to get home via the elevated railroad found themselves terrifyingly trapped high above the city.

A NEW YORK STREET is covered in snow during the blizzard of 1888.

A NEW YORK STREET is covered in snow during the blizzard of 1888.

More than four hundred people died in the storm, shocking city officials to the point that, at last, they realized the absolute necessity of constructing an underground transportation system. Mother Nature had accomplished what Beach and other subway proponents had been unable to do. It took two years for construction of the subway to begin. But Beach had been right. Within weeks of the subway’s opening on October 27, 1904, New York City’s traffic problem, at least for the foreseeable future, had been dramatically alleviated.

Within three years of its initial construction, the subway had become so popular that various extensions were being made, and Beach’s vision of an underground system throughout New York and Brooklyn was being realized. Then, in 1912, a startling event took place. As workmen dug an extension of the Broadway line, they broke through a steel and brick wall and discovered Alfred Beach’s pneumatic tunnel. There was the subway car, his tracks, his hydraulic shield, and even his fountain. Time, of course, had taken its toll, but they were all still there. Amazingly, rather than bringing these historic objects to the surface where they might be preserved and appreciated by generations to come, the workmen left them there and moved on. One cannot help but wonder what remains, a century later, of Beach’s buried achievement. Devlin’s Department Store has long been torn down and replaced by another structure, probably destroying the elegant waiting room in the process. Whatever other destruction of America’s first subway has taken place, it’s safe to say that it has been permanently buried from view.

So too has general knowledge about Beach’s other extraordinary achievements. His printing machine for the blind led to the typewriter, the machine that transformed both business and the nature of the workforce. He was a pioneer in the development of pneumatics. The magazine he established remains the world’s leading scientific journal. And his hydraulic shield revolutionized the way tunnels were dug. Yet, like his remarkable subway, his name and all that he did has been largely lost to history.