Egyptian Gardens

The climate of Egypt is very hot and dry and in a land with virtually no rain the availability of water is paramount. Most of the country is desert, except for a strip of cultivable land either side of the great River Nile plus the river delta area and a few oases. To the Egyptians their great river – the Nile – appeared to come out of the desert, from an unknown source, so its waters were seen as emanating from the gods. It became a sacred river, that was a blessing because its waters could be used to irrigate the land. Life and agriculture/horticulture developed in Egypt simply as a result of the annual flooding of the Nile. The floodwater would slowly soak into the parched earth, bringing a greater quantity of water onto the land than any man carrying water could ever manage. Also, importantly, the silt (or alluvium) washed ashore by the river was rich in nutrients, and was a very effective natural fertiliser that naturally spread over the land. Besides the annual flooding of the Nile, the Egyptians dug canals from the River Nile so that its vital water could be used for irrigation. To a certain extent the scorching hot sun in Egypt sterilised the top soil from harmful bacteria.1

Dating evidence for ancient Egypt is largely based on the reigns of the long lists of Pharaohs. For ease of identification they are grouped into dynasties, starting with Dynasty 0 around 3100 BC, down to the 30th Dynasty in 380–343 BC.2 A further simplification is to split these into the Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC), Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 BC), New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC), all these dates are approximate.

Our information about Egyptian gardens comes from archaeological discoveries, ancient texts and from depictions in paintings and carved reliefs on tomb walls. The paintings and carvings often have a religious funerary significance, but many also give details of the life of the deceased. Numerous tombs have scenes of everyday life, which are believed to show real people and objects, with the intention of continuing their existence into eternity. Therefore, the scenes represent that activity continuing for the benefit of the deceased. Most of Egyptian art is rather formalised and somewhat rigid, but the details in their garden scenes are nevertheless very informative. The majority of the tombs appear to belong to the pharaoh, his family, members of his court and other wealthy individuals. In reality however, ancient Egyptian gardens were not confined to the upper classes in palaces and temples, high-ranking officials could also have a garden, and there is also increasing evidence that workmen maintained small gardens and funerary chapels of their own, giving some indication of life at that time from a broad spectrum of society.

There are three main types of gardens in ancient Egypt and these were: sacred gardens, produce gardens and domestic/pleasure gardens. Our earliest evidence relates to aspects of sacred gardens, so those will be examined first. Religion played an important role in the daily life of many Egyptians, and it can also shed light on the meaning behind the choice of some plants that were planted in their gardens.

Fertility cults of Egypt

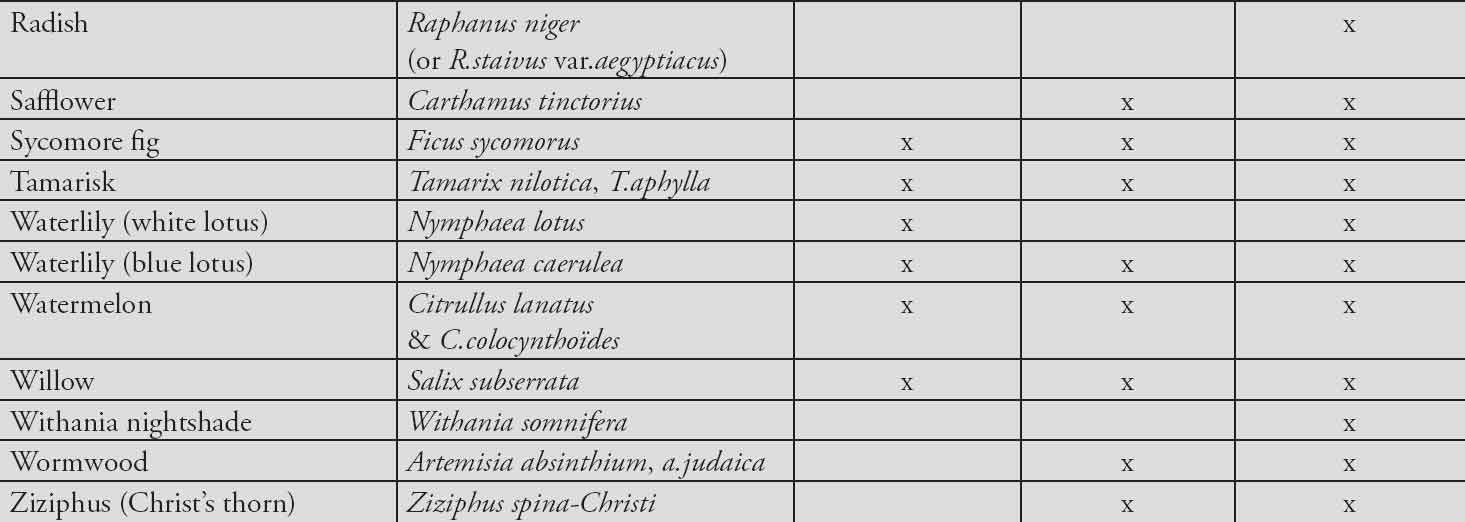

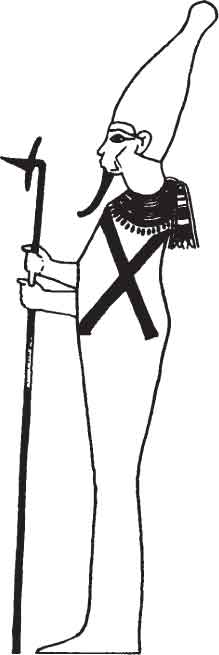

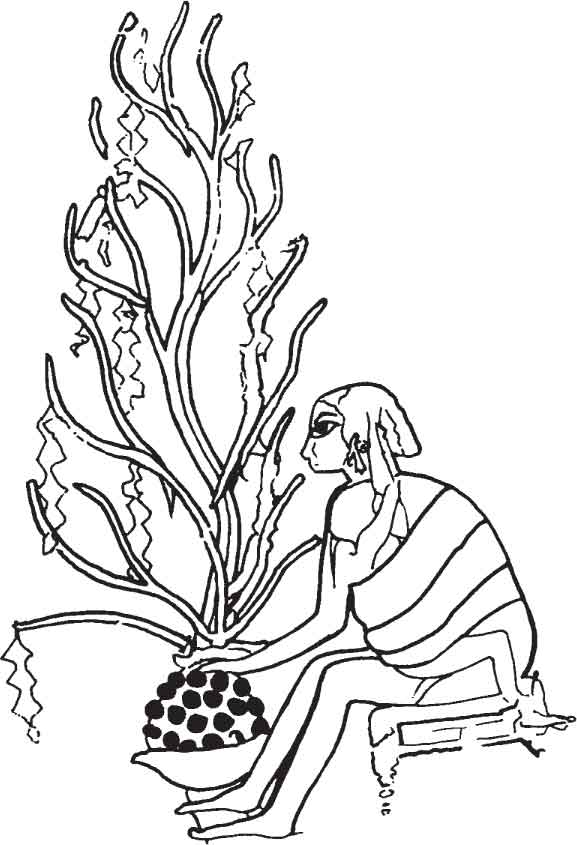

From a very early date there appears to have been a cult concerned with the fertility of crops/produce, as well as for humans, and in Egypt there are two main deities associated with this aspect: Min and Osiris. Both Min and Osiris are sometimes shown displaying their prominent symbol of fertility (an erect phallus). This is especially the case with Min whose major cult centre for his worship was at Koptos in central Egypt. A large cult statue of Min can be seen in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Images of Min in reliefs and tomb paintings often show him wearing a tall straight crown split in two, and he carries a flail in his hand held aloft. The flail alludes to his role in agriculture/horticulture. In this cult Min was given a special plant, a lettuce, and the one depicted in ancient carvings and frescoes is invariably a tall slender one similar to our ‘Cos’ type of lettuce. The shape of this lettuce would imitate that of a large phallus. Also, the Egyptians noted that when the stem of a fresh lettuce plant is cut a milky white sap exudes from the plant, and this was seen to be like semen from the god Min. So this plant became a symbol/emblem of the god himself, and as such it is also found depicted next to scenes depicting people gardening. An example can be seen in a tomb at El-Bersheh. In these scenes the symbolic lettuce has three giant leaves. Min’s worship was most active in the Old and Middle Kingdom. In the late Middle Kingdom Min appears to merge with Amun, the creator god who became Egypt’s principal god in the New Kingdom. Due to syncretism Amun also merged with Re and became known as Amun-Re, and as such he embodied the sun, that all powerful source of light and heat.

Osiris was one of the most important deities of Egypt, and because of the story of his untimely death he takes on associations with death and resurrection, but he also had an important role in assuring fertility. In legend Osiris was the son of Nut. Nut was variously a sky/nature goddess connected to regeneration rituals. He is usually depicted as a mummy. A good representation can be seen in the 18th Dynasty tomb frescoes of Tuthmosis IV, at Thebes. Here Osiris is swathed like a mummy in white wrappings and two other funerary deities are close by: one is Hathor (she is also connected to aspects of fertility and sustenance, see below). The legend, according to the full version attributed to Plutarch, says that Osiris was killed by his jealous brother Seth, who tricked him into stepping into a coffin-like box, which Seth then threw into the Nile. It washed ashore at Byblos in Phoenicia (modern Lebanon). After much searching his wife Isis eventually found it, and took the box to the marshy area around the Egyptian Delta. However, when she was otherwise preoccupied, Seth stealthily came and cut up Osiris’s remains into numerous parts and scattered them throughout Egypt. Isis dutifully searched everywhere for his remains, and buried each part where she found them (there were variously 14–42 parts, according to different sources). His phallus was never found though, because Seth had thrown it into the Nile and it was promptly eaten by carp. This legend indicates why the Nile River and its waters were considered so holy; the water of the Nile was seen as the fertilising semen emanating from the severed phallus of Osiris. To the Egyptians Nile water was literally the waters of life emanating from the god Osiris. His major shrine was at Abydos (in central Egypt) where there was an annual festival around his funerary tomb and garden. Sadly little remains of this garden, however in art his tomb is usually depicted as a mound with tall slender trees on top. In Egypt wild tamarisk trees tend to grow on a mound, so inevitably these trees/bushes became sacred to the god Osiris.

FIGURE 3. The Egyptian fertility god Min seen in his temple.

FIGURE 4. Detail of Osiris in white mummy wrappings, from the Tomb of Thutmosis IV, Thebes, 18th Dynasty.

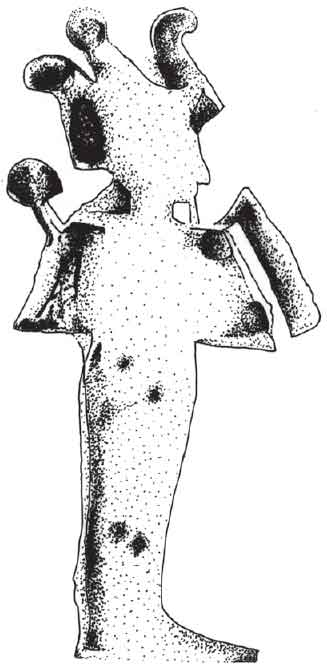

FIGURE 5. Barley seeds were sown in wooden or ceramic Osiris Beds in a ritual of regeneration and fertility in tombs, ceramic version now in Hildesheim.

Another notable feature of his cult are the special artefacts known as Osiris beds, sometimes called a ‘Corn Osiris’, these were often placed in Egyptian tombs. Several wooden Osiris beds have been found in tombs. At a later date they also made little ceramic versions. In both of these, the god’s effigy had been hollowed out of the receptacle. This depression was filled with silt from the River Nile, and then planted with seeds of barley, it was then sprinkled with holy Nile water to make the seeds germinate. This ritual symbolised the rebirth of vegetation, which was so linked to the god Osiris.3 To give an indication of the variation in size of these Osiris beds, one found in Tutankhamun’s tomb was 202 cm long × 88 cm wide, whereas a terracotta version (now in Hildesheim, another can be seen in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford) is just 24 × 10 cm.4

Another important deity was the infant falcon god Horus, son of Osiris and Isis. Horus was a sky god therefore he was often depicted with a falcon’s head or fully bird-like. He became associated with kingship. Legends say that after birth he was hidden amongst stands of papyrus in the Delta, so naturally these plants became associated with him. Re the sun god is believed to have been born from a lotus-flower. Egyptians believed that several gods were linked to particular plants, and this was reflected in ceremonies throughout the country. Therefore both papyrus and lotus plants were included into garden contexts so the appropriate rituals could be performed; these took place in sacred and domestic gardens.

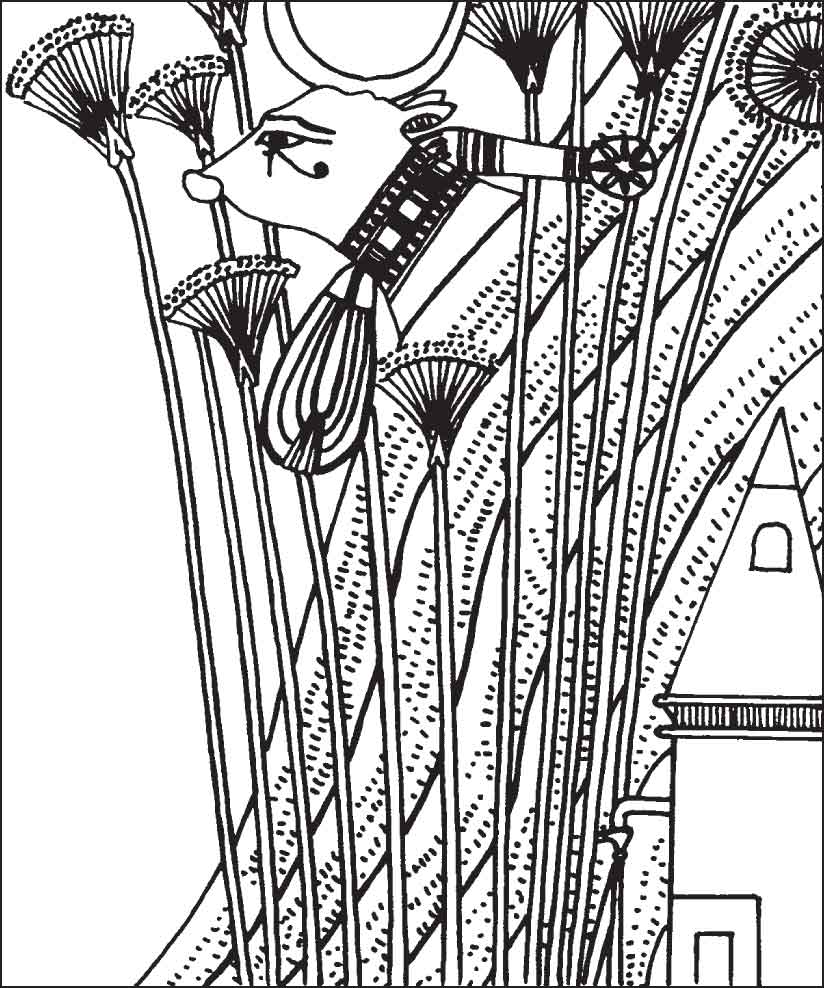

Another deity associated with papyrus was the Goddess Hathor, who was often shown with the head or body of a cow. Every day she was believed to emerge from the side of the Western Mountain coming through papyrus plants. There is a fine painting on the Papyrus of Ani (in the British Museum) depicting her in this sacred role. Hathor was linked to the role of royal mother, and at times was likened to a cow suckling its young. Hathor was the daughter of Re and wife of Horus, so it is understandable that she would also be worshipped beside the papyrus beds of garden lakes. Hathor was thought of as a protector and was sometimes referred to as the ‘Lady of the West’ because the sun set in the west. Horus was correspondingly known as the ‘God of the East’ and presided over the daily birth of the sun. The sycomore fig tree was considered sacred to Hathor in her role of nourishing the departed, and interestingly Hathor was often also titled ‘Lady of the Sycomore’. Both Nut and Hathor have this role and are occasionally depicted in female form as a goddess living in the tree, she became the tree, her lower limbs partly merging with the tree. From a tall slender vase she pours the water of life and gives food to the occupant of the tomb; this stresses the importance of this tree to Egypt. As the sycomore fig was one of the few trees that are considered indigenous to the country it had almost a sacred quality, as did the tamarisk. Both the leaves and fruit of the sycomore were used in herbal medicines.

Sacred gardens

Gardens or groves were often placed next to funerary monuments (mortuary temples, shrines and even some of the pyramids) so that rituals could be performed for the deceased and for their enjoyment in the next life. The ever present idea that their god Osiris had been restored from death to life was so strong that Egyptian tombs became almost a version of Osiris’ own tomb. Osiris’ tomb and temple at Abydos had been on an island, and around his tomb mound archaeologists found six huge brick lined plant pits that once contained conifers and tamarisk trees.5 So part of a funerary garden would need to contain a pool or lake of water to replicate the water surrounding the god’s last abode and a number of trees at least.

Religious temples were provided with gardens outside and inside the temple complex where sacred rituals could be enacted. Within the walled enclosure of the temple at Karnak there was a large area occupied by a sacred lake. The open area around it would undoubtedly have been planted as a temple garden, and the lake would have provided water for plants nearby. We can also assume this would be the case in the nearby temple of Mut, where there is an even larger enclosure with a sacred lake. Mut was the consort of Amun, hence the closeness of these two temples. Temple lakes were also used for purification ceremonies and offerings, but the lake also acted as a venue to re-enact certain legends: such as the myth of the solar sun which entailed a ritual of greeting the birth of the sun god from a lotus-flower, or of Horus from papyrus. Another ceremony that took place on the lake involved rowing a special boat across the lake.6 The boat containing a statue of the god, was believed to imitate the sun’s passage across the sky. The sun-barque would sail over what was seen as both the cosmos and a substitute of their primeval waters from which all life emerged. Because of these rituals we can assume that these lakes were all stocked with beds of papyrus and lotus so that these ceremonies could take place in a suitable setting. Temple gardens would also have contained flower beds to supply vegetables, such as lettuce for Min, as well as for flowers necessary for floral bouquets that were regularly given to images of the deities. In the Papyrus of Ani a pile of floral bouquets were given to honour the goddess Hathor. Animals and birds were also kept in pens/cages or aviaries in part of the gardens, and in some places they were bred there or nearby.7 Some were undoubtedly destined to be offerings to a god.

In several cases we can assume that a special tree was planted in sacred gardens to represent the ished tree, that was regularly illustrated on temple and royal tomb walls. It was believed that the gods, either Thoth (the god of truth) or more often Seshat (the goddess of writing), wrote the names of the pharaoh on its leaves at coronations and jubilee festivals, being designed to ensure the pharaoh’s memory. This magical ished tree is sometimes likened to the beautiful persea tree (Mimusops laurifolius) which is a large dense leaved evergreen fruit tree that has yellow oblong shaped fruits that are about 4 cm long.8

Archaeological evidence for sacred gardens

Perhaps the earliest known sacred garden are those associated with funerary/mortuary temples, such as at Dahshur, next to the so-called ‘Red’ pyramid of Sneferu, which belongs to the first Pharaoh of the 4th Dynasty in the Old Kingdom (c.2613–2589 BC). This really highlights how early this form of garden is. On the north side of the pyramid at Dahshur, archaeologists discovered a series of hollows in rows indicating pits that had been dug to plant trees, they can be interpreted as making a sacred grove on at least one side of Sneferu’s pyramid.9 The size of the brick edged planting pits indicated at least two different sizes of trees had been planted in this grove, although sadly no remains survived in the tree pits to identify which species had been planted there.10 The site at Dahshur is outside the cultivation zone, and is surrounded by desert, so to give the trees the best chance of survival the pits had been dug out of the sand and re-filled with good soil. From then on these trees would have needed to be laboriously watered by hand.

FIGURE 6. Circular tree/plant pits for a sacred grove beside the pyramid of the 4th Dynasty Pharaoh Sneferu, Dahshur, c.2613–2589 BC.

Archaeological excavations have also revealed evidence of tree planting around several royal funerary temples. In the forecourt of the funerary temple of Mentuhotep II (of the 11th Dynasty in the Middle Kingdom c.2055–2004 BC) at Deir el-Bahari they found regular rows of tree pits, which would have made a substantial sacred grove to adorn his temple. Fortunately the dry nature of the soil in Egypt has ensured good preservation of plant remains, and the remains found within these pits have indicated that tamarisk and sycomore trees were once grown there. Fifty-five tamarisks root stumps (of Tamarisk aphylla) were actually discovered in pits 10 m deep; the tamarisks had been planted in rows on either side of an avenue of sycomore trees leading up to the funerary temple, and there were two flowers beds each about 2 × 7 m.11 The sycomore is not the maple-like sycamore tree we are familiar with, but a type of fig tree, which has oval shaped leaves (Ficus sycomorus is its modern botanical name, as opposed to Ficus carica, the true fig). We will hear more of them later. The funerary garden was not complete without a number of statues of the king placed along the tree lined approach of his tomb.

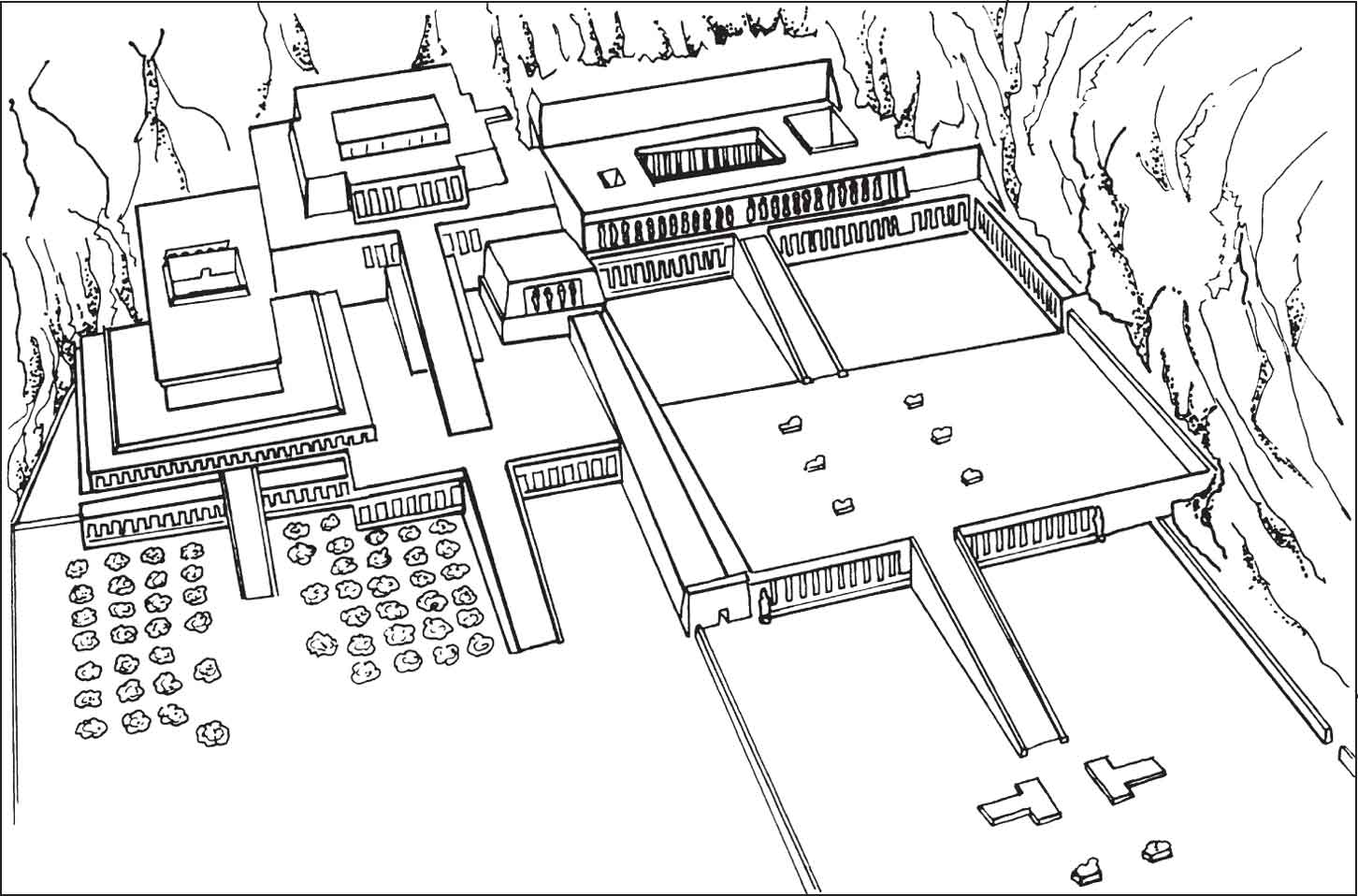

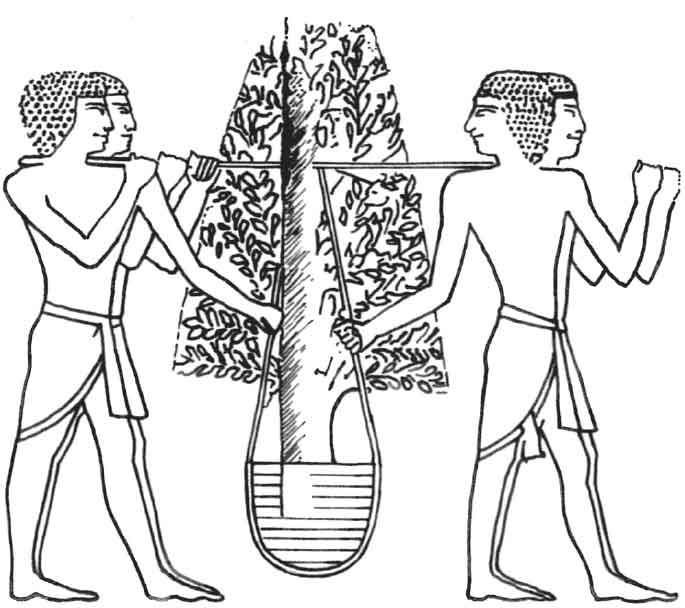

At the cliff site at Deir el-Bahari there were three royal funerary temples and tombs built cheek-by-jowl next to each other by terracing and excavating into the cliff: Mentuhotep’s is the earliest one (in the reconstruction drawing it is on the left). Later two pharaohs of the New Kingdom Period built their tombs nearby, Hatshepsut’s is on the right (1473–1458 BC), and the central one belonged to Tuthmosis III (1479–1425 BC). Hatshepsut was recorded as sending out an expedition to the land of Punt (thought to be Somalia, Ethiopia or Yemen). This was partly to collect incense/myrrh trees for her father’s temple. The events of this expedition are carved onto the walls of her temple, and in one of the reliefs we can see men carrying the said trees on a pole on their shoulders. For many years these trees were believed to have been planted in front of Hatshepsut’s temple but no remains of myrrh trees have come to light from tree pits discovered in her funerary garden and many pits are now believed to be of later date. But, in the reliefs there are also scenes showing incense trees growing in large pots and these could imply that they had been placed in the garden area to create an incense grove after all. There were however two original tree pits flanking the entry into the enclosed garden which were found to contain preserved root fragments (macrofossils) belonging to the beautiful persea tree.12 Showing that a variety of trees were judged as desirable for such a setting. On the lower garden terrace there were two large ritual pools, each shaped like a letter T. In the silt of these pools archaeologists discovered fragments of papyrus, indicating that that the rituals of Hathor emerging through papyrus could have been enacted there.

FIGURE 7. Reconstruction of three funerary temples at Deir el-Bahari, showing the position and alignment of tree pits and T shaped pools in their associated sacred gardens, from left to right: Temples of Mentuhotep, Tuthmosis III, Hatshepsut.

FIGURE 8. Relief depicting the transport of incense trees from Punt, temple of Hatshepsut, Deir el-Bahari.

Evidence of tree pits showed that Tuthmosis III’s temple also had an avenue of trees leading up to his temple. The pits here were spaced at 6 m intervals and were again very deep (10 m)13 and were found to be filled with rich black soil, brought in specially to sustain the growth of these trees. Fragments of roots and tree stumps were found there. Around each tree the ancient gardeners had built a low brick wall to protect it from encroaching sand. When watering the trees, the wall would help to contain the water and stop the precious liquid from being wasted. Every drop would be needed for those thirsty tree roots.

Excavators have also found garden areas within the Ramesseum, the funerary temple of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) at Thebes. A representation of the garden featured in the tomb of Nedjemger (Theban Tomb 138) who was its head gardener; this sacred garden comprised a T-shaped pool/canal and an orchard or grove.14 Sadly there are no remains of this garden today. However, at Medinet Habu Ramesses III (1184–1153 BC) constructed another magnificent funerary temple complex which he called his temple of ‘Millions of Years’. The huge temple complex itself was surrounded by high walls, as were many temple gardens. Between the entrance gate and the first pylon archaeologists discovered a pool and evidence for a row of trees, then beyond the first pylon gateway and the temple itself, there had been a grove of at least thirteen trees grown in pits protected with low walls. The trees had been planted in three rows 3.50 m apart.15 A further enclosure was furnished with a T-shaped pool and a well 5 m deep. No plant remains are recorded but we know that gardens once flourished here as Ramesses himself informs us that the temple was:

surrounded with gardens and arbour areas filled with fruit and flowers for the two serpent goddesses. I built their dwellings with windows, and dug a lake before them supplied with lotus flowers … I dug a lake before the Temple of Millions of Years, supplied with lotus flowers, flooded with Nun, planted with trees and vegetation like the Delta.16

FIGURE 9. ‘The Botanical Garden’ detailing plants brought to Egypt after the campaigns of Tuthmosis III, Karnak Temple (photo: © J. Chisnall).

FIGURE 10. Hathor emerging from the side of a mountain through papyrus.

Nun was the primeval waters from which the primeval mound of earth emerged, therefore in Egyptian gardens the concept of a lake with an island originated as a recreation of this early creation myth. The mention of ‘Delta’ like vegetation probably implies papyrus beds growing at the edge of the lakes mentioned. Apart from the lotus/waterlilies, garden plants are again just mentioned collectively but the species known at that date will be discussed later.

At Amarna, the royal city built by Pharaoh Akhenaten (1352–1336 BC) in Middle Egypt, archaeologists have uncovered two important sacred enclosures, that were in effect walled parks lying side by side, located to the south of the main city. Of the twinned parks called the Maru-Aten, the northernmost is significantly larger and appears to have been associated with royal women. The gardens were designed to make a fitting place on earth for Aknenaten’s monotheistic god, the sun who was now called the Aten, he replaced Amun during this heretical period. Both of these gardens have lakes within them, and some buildings around their periphery, but the centre of the northern sacred garden was occupied by a vast sacred lake that was orientated east–west. On the west side of this lake there was a jetty, to enable the royal family and temple priests to sail across the lake to re-enact the ritual of the sun’s passage across the sky and over the sacred waters. The lake was roughly rectangular in shape with rounded corners and was about 120 m long by 60 m and 1 m deep.17 On the opposite side of the lake (to the east) there was a small temple. Some of its columns were decorated with painted waterlilies, leaves and bunches of grapes. Beside the lake archaeologists noted traces of cultivation plots.

Immediately to the north of the small temple within the Maru-Aten Akhenaten constructed a moat surrounding an artificial rectangular island with a small open sided pavilion in the middle. Some paintings on the outside of the shrine featured palm and acacia trees and lakeside plants such as waterlilies, papyrus and reeds, while in the interior several wall tiles were found to be decorated with flowering plants.18 This pavilion also had columns with lotus-flowers in relief and palm leaf/papyrus capitals, it was indeed a highly ornamental garden-like pavilion. A bridge gave access to this sacred island and to the rear of the shrine another bridge led to an area of cultivation strips which are believed to form ten rows of flowerbeds. A path through these beds led to an elongated enclosure with a series of 11 interlocking T-shaped offering pools, each 6 m long. Interestingly the floors around these pools were of painted plaster, depicting a variety of beautifully painted flowers and plants, as if they were in rectangular plant beds on either side of the pools. These colourful floor frescoes featured clumps of reeds, papyrus, cornflowers and poppies (several are now on display in Cairo’s Archaeological Museum). One section of the painted floor resembled a basket full of flowers and on the low walls surrounding the pools there were scenes with vines and pomegranates. These plants and flowers are representative of the many that would have been needed to make bouquets and offerings to the god, and part of the relief carvings in this Maru Aten shows priests bearing bouquet offerings. A Maru means a sacred place, and this delightful example provided a suitable residence on earth for Aknenaten’s supreme god where the divine sun would shine onto the pharaoh imbuing him with divine power. A poem dedicated to the Aten shows the depth of Egyptian sentiment for flowers, one part says: ‘By the sight of your rays all flowers exist, what lives and sprouts from the soil grows when you shine …’19

While excavating areas within the Workmen’s village at Amarna a number of the workmen’s funerary chapels were brought to light. It was exciting to learn that two of these were found to have a little funerary garden associated with the chapel. These examples show that in ancient Egypt gardens were tended by a wide section of the population. Chapel 528 had a T-shaped pool of about 5 m in length and small garden plots edged with stones and or mortar.20 The forecourt to Chapel 531 however had a central path with garden plots on either side, both were again edged with stones. A tree pit was located nearby. Due to the dry conditions in Egypt it has been possible to conduct botanical analyses of the soil deposits in the Workmen’s village and within the garden plots macrofossils were found of coriander and celery, seeds of black cumin, juniper, beet, possibly basil, and capsules of what appears to be white mustard or radish.21 Also, there were flower heads, leaves and seeds of species that would have provided material for making floral tributes such as a species of aster and withania nightshade. The remains of Christ’s thorn, acacia and tamarisk are believed to represent shade trees grown in these gardens.

Produce gardens and gardeners

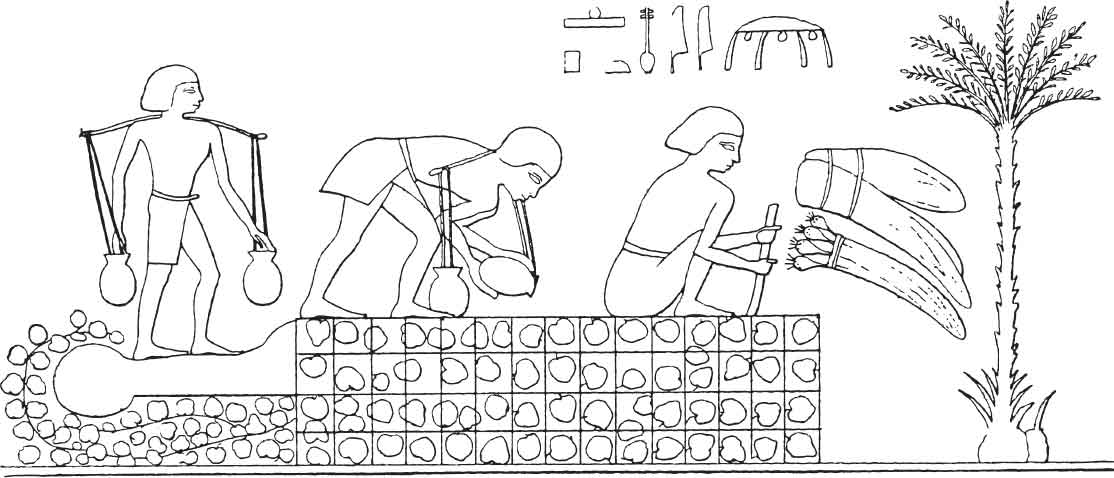

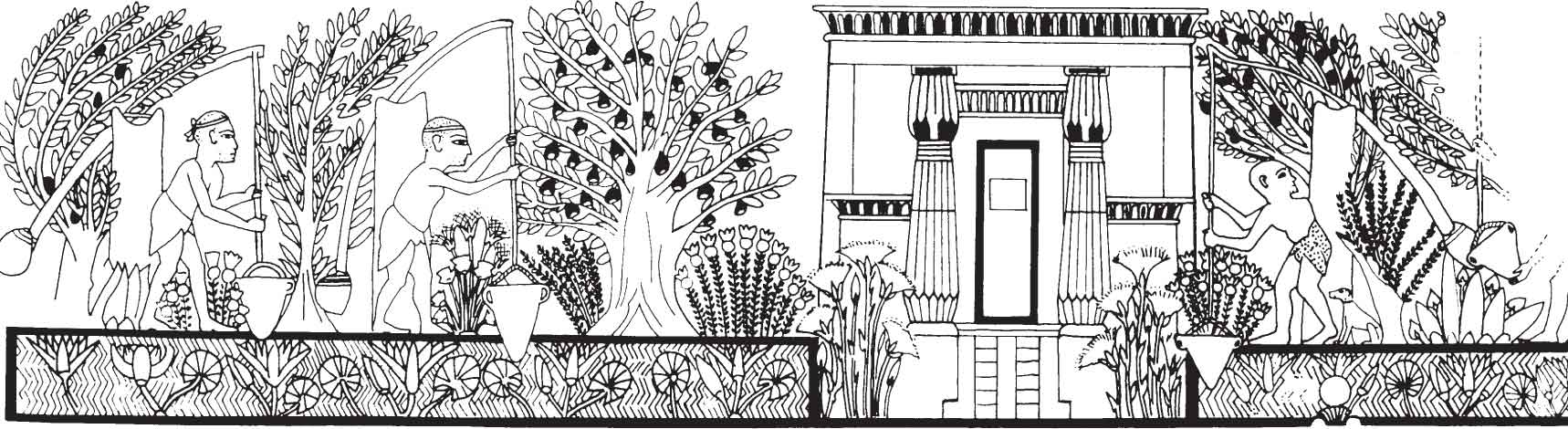

Several temple and tomb reliefs depict agriculture and horticultural occupations. The earliest found in a private tomb were those in the Tomb of Mereruka at Saqqara. Mereruka lived during the Old Kingdom 6th Dynasty, so produce gardening can be dated to c.2330 BC at least. The relief shows gardeners carrying water-pots suspended on a yoke, they irrigate what appears to be a grid of square plant beds. Behind them larger than life representations of plants serve to indicate the produce growing there. In the dry climate of Egypt a water-carrier’s work was continual and very hard to bear, and his sorry plight is highlighted by a rather melancholy ancient Egyptian text that makes a satire on the different trades in Egypt; it implies that the water-carrier’s lot was the hardest of all to bear.

The water-carrier carries his shoulder-yoke. Each of his shoulders is burdened with age. A swelling grows on his neck, and it festers … He spends the morning in watering leeks and the evening [with] corianders, after he has spent the midday in the palm grove … So it happens that he sinks down [at last] and dies because of his hardship, more than any [other] profession.22

A series of Middle Kingdom reliefs from tombs in Beni-Hasan and El-Bersheh (in Middle Egypt) show more of these square grid-like vegetable beds. Archaeologists have found the same pattern of plant beds, and in places a similar system is still used for ease of irrigation. In Egypt plants relied solely on the water that was brought to them, there was no rain, so in such places narrow straight paths enabled gardeners to walk between a series of grids, and from there they could lean across to water or weed the beds. In the ancient relief in the Tomb of Khnumhotep at Beni-Hasan two gardeners (again water carriers) approach the square vegetable beds and water the plants, while on the right a gardener bends down to tend the bed. To the right of this gardener there is a representation of the vegetables they are producing: a large bunch of onions and two tall cos type lettuces.

FIGURE 11. Middle Kingdom relief depicting water-carriers irrigating a grid-like plant bed, and gardeners toiling in vegetable gardens. The over-large symbolic representation of a bunch of onions and two cos-type lettuces indicates what was planted there, Beni-Hasan (after Gothein 1966, 1, 8).

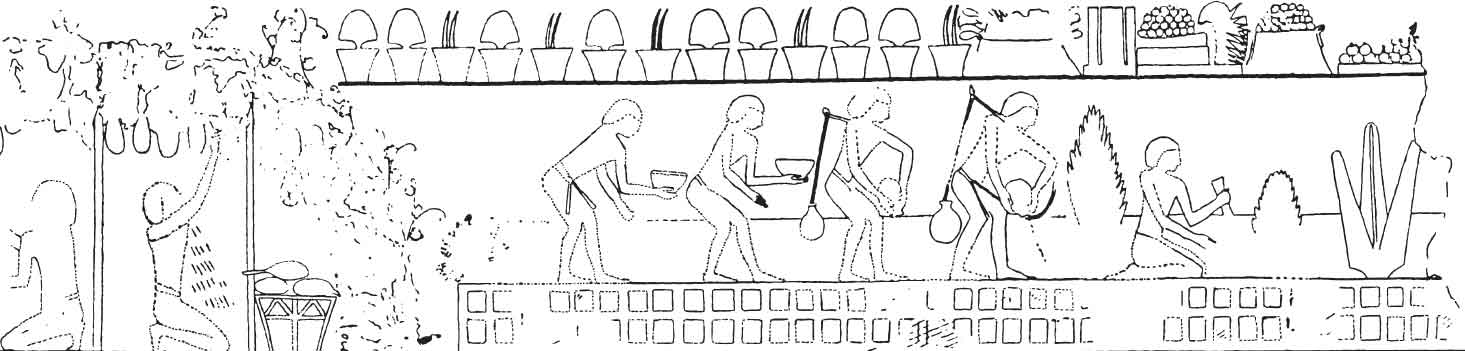

FIGURE 12. On the left, gardeners pick cucumber-like melons. On the far right the huge lettuce symbol of the fertility god Min ensures a good crop. A row of potted plants and baskets of fruit show how productive is the garden, El-Bersheh, Middle Kingdom (after Gothein 1966, 1, 9).

In a similar horticultural scene, from a tomb at El-Bersheh, we see gardeners picking cucumber-like vegetables grown on a trellis frame, these are however a species of melon grown at that time called cucumis melo chate.23 To the right of this image gardeners sow seed and water the square plant beds. On the right another gardener kneels down to weed. To the far right is a different depiction of a huge cos lettuce, it is stylised and has three large leaves, this image is the sacred sign/symbol of the fertility god Min. The owner undoubtedly was hoping that the god would help his crop, and part of it would have been dedicated to the god as a ritual offering. Along the top of this scene there are baskets of picked fruit next to a row of potted plants perhaps being special pot herbs or young plants ready to plant out.

The most frequently mentioned garden vegetables and those that are depicted in reliefs and frescoes are: lettuce (Lactuca sativa), cucumber-like melons (Cucumis melo chate), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), celery (Apium graveolens), onions (Allium cepa), garlic (Allium sativum) and leeks, however the leeks were not the European species but the kurrat variety (Allium kurrat).24 Tuberless radishes (Raphanus niger or R.sativus var.aegyptiacus), and the herb coriander (Coriandrum sativum) were also frequently mentioned in garden contexts, although we cannot identify them in garden scenes.

FIGURE 13. Detail of a vintage scene, a process undertaken in many gardens. The vine roots are protected by a meru container, Tomb of Kaemwaset, Thebes, 19th–20th Dynasty.

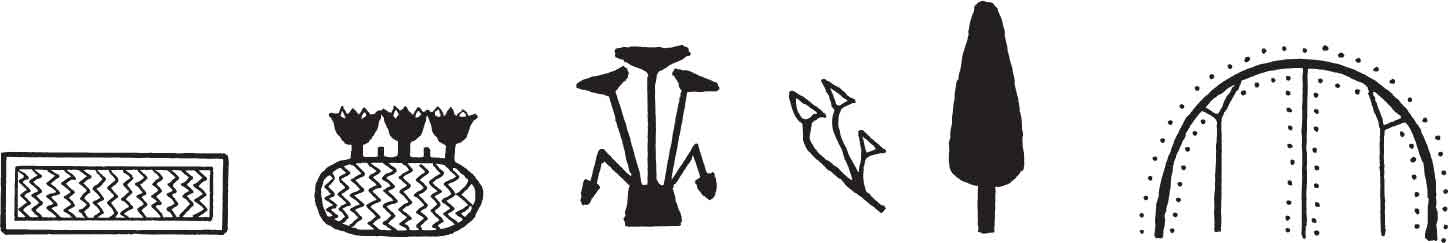

FIGURE 14. Figurative hieroglyphs, from left to right: a pool, lotus, papyrus, plants, tree, a vineyard.

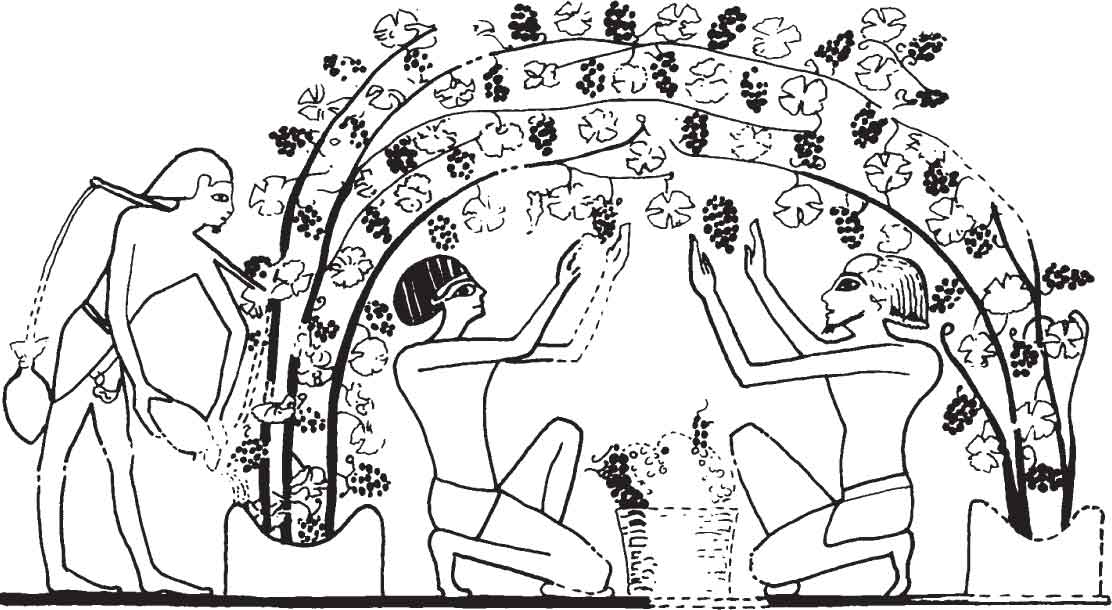

Vines were introduced into the country at an early date, and scenes of the vine harvest are found. In a Middle Kingdom tomb relief from Beni-Hasan gardeners are shown picking grapes from vines trained to grow in the form of a semicircular bower. To the left a man carries away two baskets full, suspended from a shoulder yoke. A similar scene is reproduced in one of the New Kingdom frescoes in the Tomb of Khaemwaset, at Thebes (TT261). Here the gardeners kneel down to pick grapes from vines growing over a bower. Part of the painting (now damaged) shows a basket between them for their picked fruit. A water carrier gives the thirsty vine tree a perpetual drink, he pours the water directly into the trough-shaped plant container that served to protect the vine’s roots and the raised sides make watering the plant easier. This was a meru container.25 Nearby there were additional scenes showing various stages of bringing in the vine harvest, and processing it. Workers tread the gathered grapes, and finally there is the bottling of the wine. Such time honoured scenes would have been performed in many large Egyptian gardens. Interestingly, the figurative hieroglyph for a vineyard resembles the way Egyptian vines were trained to grow in the form of a bower, two forked poles hold up the arching vine stems. Several hieroglyphs are recognisable symbols that alert us to the mention of a tree, flowers or plants in general, papyrus, lotus (growing in a pool), and any form of pool – in this case shown as a traditional rectangular shaped one with wavy lines to represent water.

The ancient Egyptian term for a gardener was khenty-esh this seems to have come into use during the New Kingdom; before that the term applied to an attendant or a land planter.26 During the New Kingdom we hear of the title ‘Overseer of the Garden’ (imy-r Khenty-esh), such as Nedjemger who presided over the Gardens of the Ramesseum.27 There was also a ‘Gardener of the Divine Offerings of Amun’ and Nakht was such a fortunate person. He would ensure the well-being of all growing plants within the temple gardens and arrange for the collection of vegetables, fruits and flowers that would comprise the god’s offerings. There are even recorded incidences where the post of a temple gardener had passed down the generations from father, son, then to grandson, as seen in inscriptions in the 18th Dynasty Tomb of Nakht the Gardener (Theban Tomb 161).28 Nakht also had the honour of a second title ‘Bearer of the Floral Offerings to Amun’, for details of these bouquets see below. One section of Nakht’s tomb wall paintings actually depicts him overseeing his workforce of gardeners watering the grid-like garden plots.29

Water was drawn up by hand, by lowering a water pot into a well, pool, or water channel. Also, in Egypt agri/horticulturalists made good use of a shaduf. This devise was a great help to gardeners, in time and energy. A stout pillar was placed at the water’s edge, and a large pole or tree branch was pivoted on top. A water pot or canvas container was roped to one end of the pole so that it could be lowered into the water. Because the pole was counterweighted at the other end the filled water container could be raised almost effortlessly, then the water could be emptied into the water-carrier’s pots. A shaduf is shown in several tomb paintings. In the tomb fresco of Ipuy’s garden (TT217, of the 19th Dynasty) four shadufs can be seen in action. Apparently the waterwheel was not known or used during Pharonic times, they are believed to have been introduced at a later date possibly during the Ptolemaic period.

Beside tending the trees, vegetables and flowers, Egyptian gardeners would have had to ensure that birds and baboons would not come into the garden to eat the carefully cultivated vegetation or the fruits on the trees. Some gardeners were provided with sticks to scare the predators away, as seen in the Middle Kingdom Tomb of Bakt at Beni Hasan.

An inscription on a 22nd Dynasty stele discovered at Abydos mentions the purchase of an estate and land at Abydos providing details of prices paid for each item – including a garden and its workstaff.30 This inscription gives a good comparison between the various ranks of staff employed there and of their worth. Two parcels of land were bought (each measuring 50 stat) costing 10 deben of silver money. A deben and kidet (or kit/kite) were units of silver weights. A modern equivalent could be lbs and ounces, 10 kidet/kit = 1 deben.31 The garden at Abydos cost 2 deben of silver, its gardener Harmose son of Pen-mer was priced in kidets. Unfortunately the inscription is damaged at this point, but the gardener appears to have been priced in double figures of kidets. His watercarrier (sadly his name is missing) cost six kidets of silver. In comparison two named maidservants were priced at 5 kidets each, and workers in the spice-kitchen and harvest labourers were 1 kidet each.

Orchards

Orchards are also depicted in tomb reliefs and are mentioned in texts. The earliest description of what could be an orchard is that of Meten, a general and high official living c.2600 BC during the 3rd/4th Dynasty. He planted numerous trees, including palms, figs and vines.32 We hear that Ramesses III (c.1184–1153 BC) created an orchard of 200 persea trees at Heliopolis for a new temple of Amun.33 Whereas a large variety of trees are mentioned by Ineni, the architect and royal gardener to Tuthmosis I of the 18th Dynasty (c.1504–1492). He mentions in his tomb (TT81) that he once had 540 trees in what must have been a large garden or orchard in which he hoped to enjoy in perpetuity. He names 20 different species of tree but only fifteen can be identified with reasonable certainty, they comprised: 170 date palms (Phoenix dactylifera), 120 doum palms (Hyphaene thebaica), 73 sycomore fig trees (Ficus sycomorus), 31 persea (Mimusops laurifolia), 16 carob trees (Ceratonia siliqua), 12 grape vines (Vitis vinifera), 10 tamarisk trees (Tamarix nilotica/T.aphylla), 8 willow trees (Salix subserrata), 5 fig trees (Ficus carica), 5 pomegranate trees (Punica granatum), 5 Christ’s thorn trees (Ziziphus spina-Christi), 5 twn trees (possibly a form of acacia), 2 moringa trees (Moringa peregrina), 2 myrtles (Myrtus communis), 1 argun palm (Medemia argun), and 5 unidentified species of tree.34 In Egypt fruit bearing trees tended to be planted in rows so that an irrigation channel could be dug alongside, alternatively the trees were planted in a series of plant pits but there was still a tendency to plant these in rows. Again these were all laboriously watered by hand. The orchard had to be planted in the dry zone because if it was planted in an area which periodically flooded, the tree trunks would rot after several months under water.

Inside a small room in the great temple complex of Amun at Karnak there is a surprising series of relief carvings of trees and other plants, which has led to this room being called ‘The Botanical Garden’ (see Fig. 9 above). The rows of carvings actually record the plants that were considered notable on Tuthmosis III’s campaigns in the Levant (c.1479 BC); they were conquests albeit botanical ones, and were considered worthwhile to introduce into Egypt. A special orchard or garden would have been provided at Karnak for these trophies. Unfortunately the plants were not labelled, and the style of the carvings is rather stylistic and not drawn to scale therefore it is very difficult to identify the species represented. A few are however recognisable such as: pomegranate, palm and fig trees, vine, lotus, melon, lettuce, myrtle, asphodel, iris and a daisy-like flower.35 Sadly in the extremely dry climate of Egypt several of the trophy plants would not have survived long without continual care.

Domestic pleasure gardens

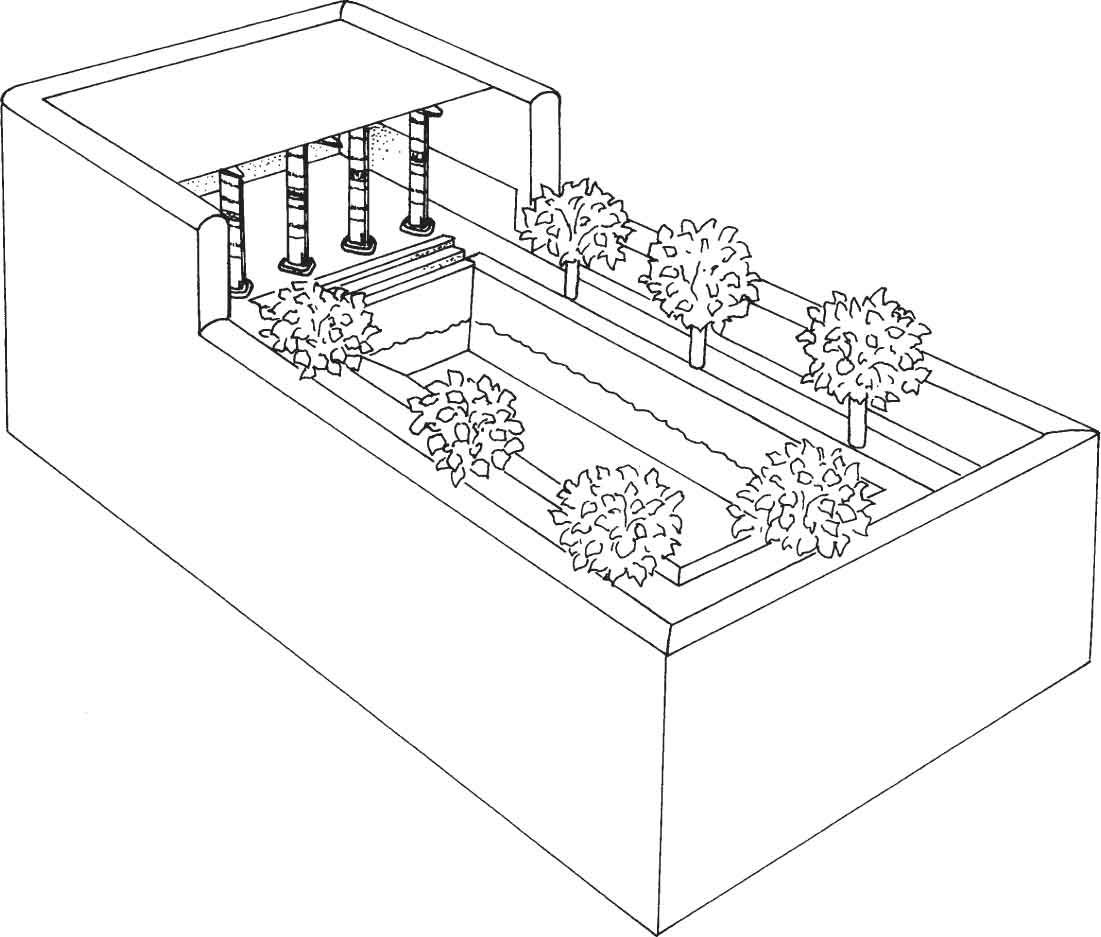

Inscriptions in private tombs, for example that of Meten (c.2600 BC), suggest that from an early date Egypt’s elite could possess their own enclosed garden that would surround their private villa. He informs us that his estate was walled and enclosed a square of about 105 m on each side, filled with trees, arbours and pools for water fowl, he also had a vineyard nearby.36 Sadly no garden of this early period has survived but from later representations of gardens (whether real or imagined) it is clear that a water source was thought desirable in a garden and a well or pool became a central feature. Pools were usually rectangular or T-shaped. Trees and flowering plants were often planted in beds near the pool because the plants could then be irrigated using water drawn from the pool. This is shown to good effect in one of the remarkable wooden models found in the Tomb of Meketre (TT280) who was a chancellor to Mentuhotep II of the 11th Dynasty (c.2055–2004 BC). These models represented boats, houses, or craftsmen at work, all with the intention that the activities represented within them could continue in eternity for the benefit of the deceased in their next life. Two of the models represented a house and garden. The whole was surrounded by a high wall. The house is simply represented by just its columned portico, opening onto the view of a deep pool surrounded by seven trees, believed to be of sycomore figs.

Gardens tended to be located on the north side of buildings, presumably so an open portico on that side would allow any cool breeze from the north to temper the heat inside. The building would also create some welcoming shade in nearby garden areas for part of the day. Trees were also valuable for the shade they gave in a garden, other plants could be grown below their dappled canopy, and an area of seating could be quite welcoming if you wanted to sit out and enjoy the fresh air outside.

Depictions of gardens

Most of our evidence for Egyptian gardens is revealed in the details shown in contemporary tomb paintings and reliefs. Many garden scenes in frescoes date to the New Kingdom, and in particular to the 18th Dynasty (1550–1295 BC) which saw a flowering of artistic skill. The classic elements depicted in these garden scenes are a rectangular or square pool surrounded by plants. Less frequently we see a T-shaped pool,37 but there does not seem to be any desire to install a pool of a different shape. A rectangular pool was practical, and also would have been easier to construct than one of a more irregular form. The frescoes vary in content, however, for instance in the 18th Dynasty Tomb of Minnakht (TT87), and the Tomb of Rekhmire (TT100, both at Thebes), a boat sails across a lotus filled rectangular pool. The boat is believed to represent a festival or funerary ritual. In the former we see various trees: date palms and sycomore figs, and also covered areas where storage jars are kept cool and fresh by hanging foliage from the rafters, they are shown dangling between each large pot. This may show a method for keeping flies off the produce stored there. In the Tomb of Sebekhotep, at Thebes (TT63), he and his wife drink from their centrally placed lotus pool, while fish swim about. This would be a re-enactment of them taking the sacred water of life to sustain them in the next world. To reinforce this concept on either side a sycomore tree goddess presents food and liquids for sustenance throughout eternity. Two rows of trees surround the pool, all shown laden with fruit.

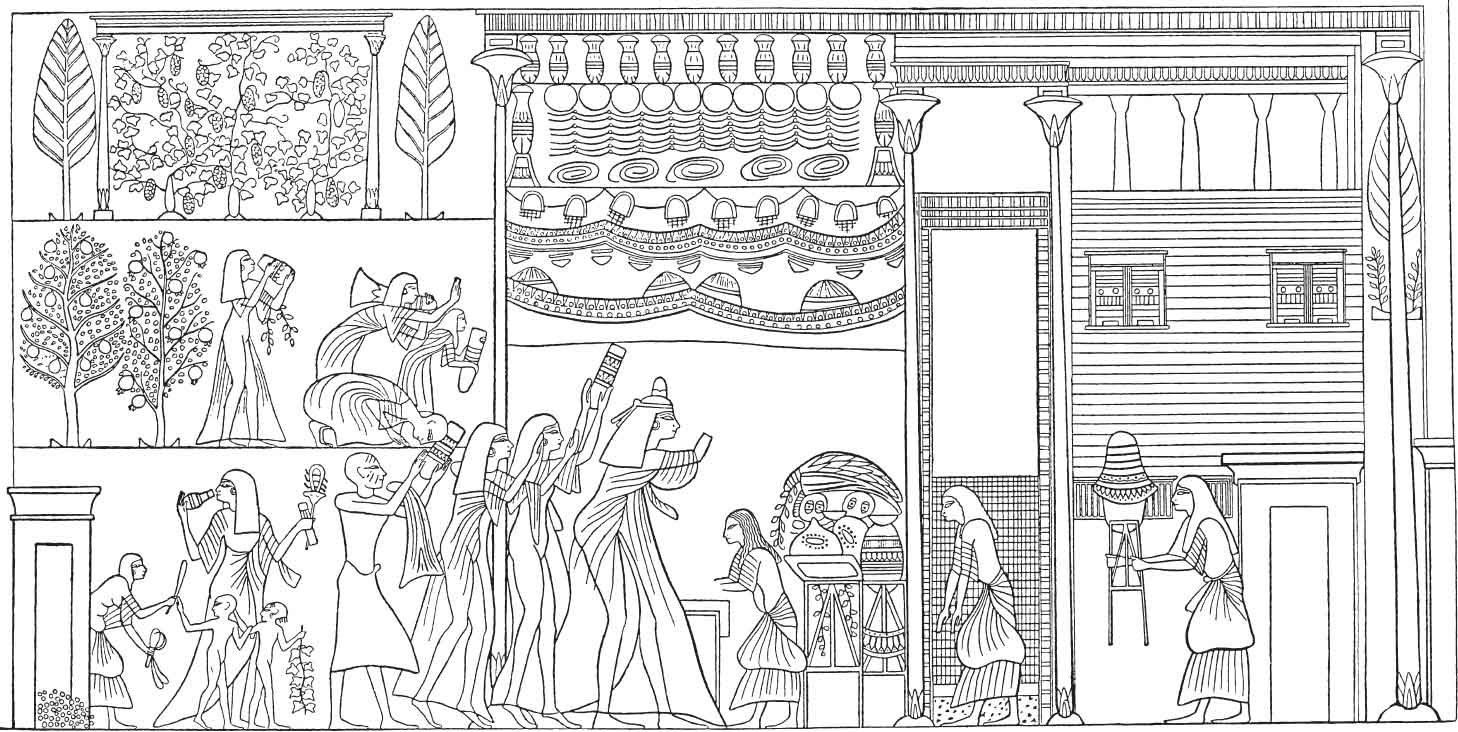

FIGURE 15. Wooden model of a part of a house and garden, placed in the Tomb of Meketre, 11th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom Period. Seven trees surround a deep pool in the garden.

Garden scenes are often painted as if from a bird’s eye view, but with the plants drawn in profile, so that the scene is reminiscent of a plan. No perspective is shown. Some artists however chose to include a scene depicting a profile view of the owner’s house and garden, as in the Tomb of Ineni (TT81). In the Tomb of Neferhotep at Thebes (TT49) we see a lively scene depicting visitors arriving at a villa in Thebes. They proceed through the gateway on the left; the house and welcoming party are on the right. Some guests walk through the gardens. There is a fine vine covered pergola above, with lotus-like columns. The trees below are pomegranates, that can be clearly identified by the characteristic remnants of its flower protruding out. Pomegranates were an introduced fruit tree highly valued for its flame coloured flowers, as well as for its sweet juicy fruit.

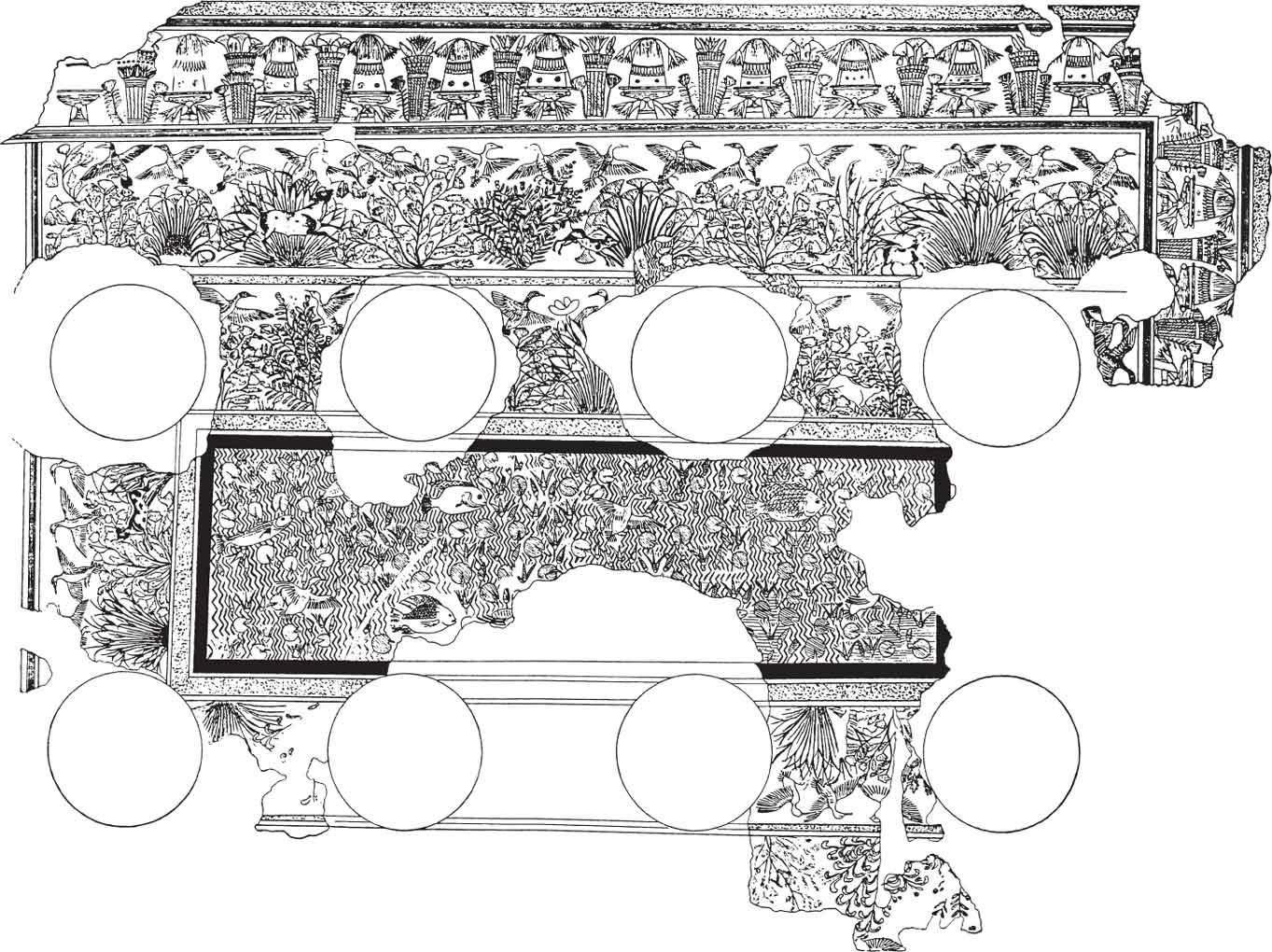

FIGURE 16. A flower filled garden around a well stocked fish pool painted on the floor of Room E in Akhenaten’s Palace at Amarna, 18th Dynasty. The blank circles mark the position of columns.

There were also wonderfully painted plaster floors with garden scenes, and several have been discovered in the great palace at Amarna (dated c.1350 BC). The newly built city was abandoned after the death of the heretical pharaoh Akhenaten after only 25–30 years therefore the site preserves valuable evidence of this particular period. The floor paintings give a marvellous indication of the possible appearance of a royal Egyptian palace garden. Although they were painted inside buildings they were meant to represent gardens outside. The scenes (painted as seen from above) are fragmentary. In the ‘Main Room’, which is the most damaged, the floor appears to show four rectangular fishponds; while in Room F the ‘garden’ features a pair of elongated rectangular fishponds. However, in the better preserved ‘garden’ within Room E the centre is occupied by a single large rectangular fishpond; this floor painting measures 15.6 × 6.5 m.38 All fishponds in the three rooms were outlined with a dark border and there is a path around each pool. Blue wavy lines reflect water in the pond and all are shown teeming with fish, ducks and lotus plants. Flowerbeds and reeds surround these ponds. In room E a second row of plants decorated the two long sides. Wildfowl fly above the foliage, and deer bound through the clumps of plants, bringing life to these delightful scenes. These ‘gardens’ all show abundant healthy plant growth, and this concept is reinforced by an outer painted border composed of facsimiles of offerings and bouquets.

FIGURE 17. Plan of the house and garden of Meryre, High Priest of Amarna, Tomb of Meryre, 18th Dynasty (after Gothein 1966, 1, 13).

Fortunately some of the officials of Amarna have also left tomb wall paintings that depict what may have been their own home and garden in life, helping us to visualise how they would have appeared in reality. A good example is that of Meryre, the High Priest of Amarna. In this fresco, which resembles a plan, his large residence is surrounded by a rectangular wall; the entrance gate is shown at the bottom. Large trees shade the first enclosure on entering the property, the trees may be sycomore figs. Each tree has a low retaining wall of dried mud, which is shown in cross-section; these would be the meru receptacles/containers which were made of brick/mud. Immediately in front of the house and storeroom block there is a large rectangular fishpond, with a means of access placed in line with both entrance gateways. Large areas are reserved as living quarters, for Meryre himself and his staff which included his gardeners. The central route through the numerous storerooms (on the left) led to a large decorative garden (top left in the fresco drawing). This was designed with a large deep square shaped pool, slightly off centre in the garden. Between the garden gateway and the pool Meryre had installed a garden pavilion/kiosk so he and his family could relax and enjoy his garden, in the shade, and benefit from cleaner air emanating from aromatic foliage and flowers in the garden. A variety of trees and bushes were grown here, of these we can identify palms, figs, and tamarisk.

FIGURE 18. Sycomore fig tree with tree goddess dispensing nourishment for eternity, Thebes (after Rosellini Monumentii, Pisa, 1832–44).

The pool in Merye’s garden had a flight of steps located on the bottom right corner, to enable gardeners to draw water from it. Several garden representations show deep pools and it appears that this was specifically done to enable groundwater to seep into the pool, especially after the annual floods. When the surrounding water-table fell the water in the pool would also fall so the steps would enable the water-carriers to reach the shrinking water level later in the year. There was no piped water supply so garden pools were filled in this way or by slaves laboriously transporting water from the Nile to the pool by hand.

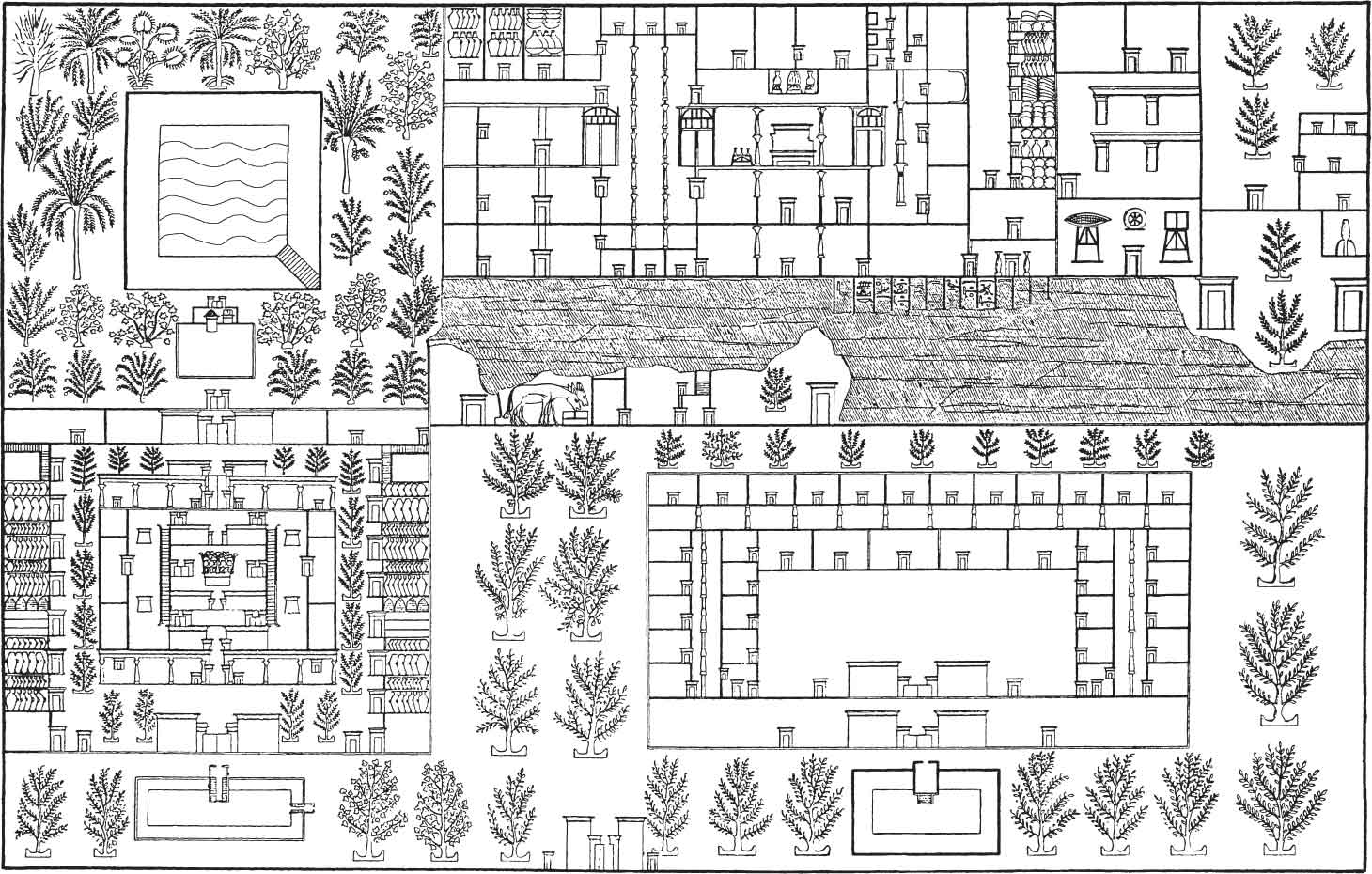

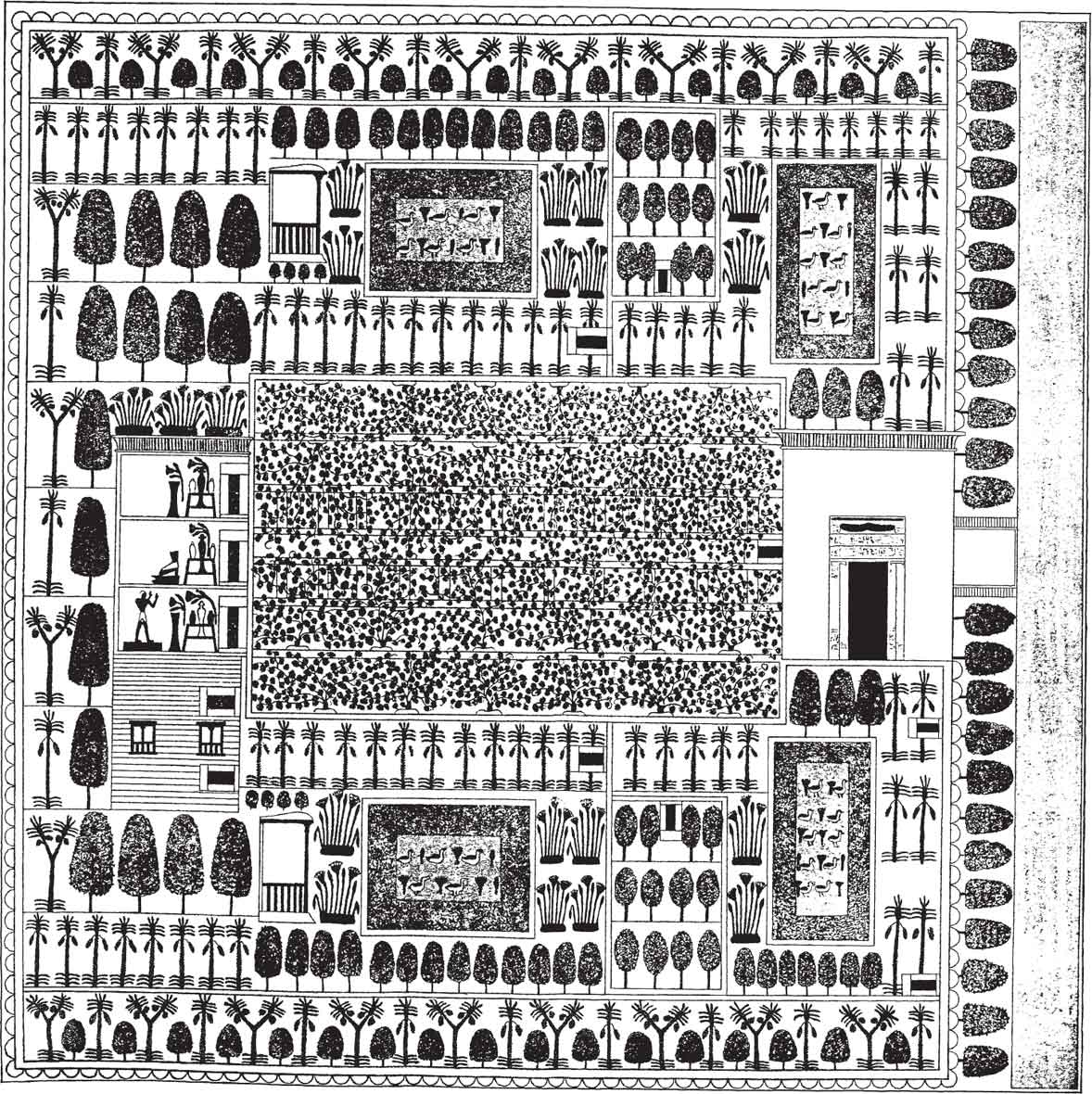

The most extensive plan of an Egyptian garden was painted on the walls of Sennefer’s tomb at Thebes (TT96, c.1427–1400 BC). One of Sennefer duties was to be the overseer of the Gardens of Amun, therefore as you would expect his gardens would be special. The walled garden is shown fronting onto the river or canal, and has a tree lined aspect. The shape of the large trees on the river front indicate two different varieties are represented here, probably the sycomore and persea which are often similarly drawn. One has a rounded appearance whereas the other has a relatively more pointed shape, the latter would be the persea (Mimusops laurifolia). As you entered through the large red door of the gateway (here all doors are painted red) you would immediately notice that the layout of the garden is formal and almost symmetrical. The centre of the garden is completely occupied by thriving grapevines supported on wooden pergolas. On either side a smaller red doorway opened into a separately walled section of the garden which comprised a rectangular pool surrounded by more sycomore trees, date palms and special beds growing papyrus flowers. Then, inside these gardens were other walled enclosures protecting twelve pale green trees with dots – these would be tender fruit trees. To the north and south the garden is edged with a border of alternating palms and green trees.

FIGURE 19. Plan of Sennefer’s garden. The centre is covered by grapevines, and on either side are separately walled fruit orchards, and four fish pools surrounded by papyrus beds and trees: sycomore, date and doum palms, Tomb of Sennefer, Thebes, 18th Dynasty.

Two different species of palms are shown in the border of Sennefer’s garden. One is the familiar date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) which is ubiquitous in Egypt and the Middle East. The second is the doum or dom palm (Hyphaene thebaica) – both spellings are current. The doum palm has a more rounded pattern of palm fronds and has a distinctive bi-forked trunk. Sadly now it only grows wild in Upper Egypt and in desert oases and is relatively rare elsewhere.39 It was though once a very popular tree. Ineni, a military chief living in the 18th Dynasty at Thebes, mentioned that he had no less than 120 doum palms in his garden, and Ramesses III is recorded as having planted doum palms in Heliopolis. It was prized for its fruits, as well as for its graceful appearance, but later it was found to be more useful in the building trade and this decimated its range. However, there is a third species of palm known in ancient Egypt: a fan palm called the argun (its botanical name is Medemia argun). It is like the doum palm, but its trunk is unbranched, I believe that it is represented in a fresco in the 20th Dynasty Tomb of Pashedu at Deir el-Medine (TT3). The fruit of the argun palm is edible, but is rather stringy. It is now quite rare in Egypt, but apparently it was also a popular garden tree in ancient times. Ineni had ensured that at least one of these palm trees was in his garden. In the fresco Pashedu is shown bowing down behind the argun tree and is about to drink the water of life, from a clear blue pool painted below. It can be noted that the fruits of all three forms of palm trees were often placed in tombs. In some museums (such as the archaeological museum in Florence) there is a well preserved basket full of doum fruit, they are about the size of an apple. In the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford you can compare the shape and size of a desiccated doum palm fruit with a sycomore fig and grape pips that had been discovered well preserved in the dry conditions of ancient Egyptian tombs.

FIGURE 20. Doum palm tree (Hephaene thebaica), Silsila, Upper Egypt (photo: © 2012 Brian Yare)

FIGURE 21. Argun palm tree (Medemia argun), Tomb of Pasedu, Deir el-Medinet, 20th Dynasty.

FIGURE 22. Visitors arrive through the garden. At the top grapevines grow under a pergola; in the row below there is a fruit laden pomegranate tree, Tomb of Neferhotep, Thebes, 18th Dynasty.

FIGURE 23. Flame coloured flowers of Pomegranate (Punica granatum), Cyprus.

In Egyptian art the trees and flowers are formalised, and it is sometimes difficult to identify them. However, in the Tomb of Pashedu (TT3 at Deir el-Medinet), one of his frescoed walls has a good representation of one of the most important trees in Egypt, the evergreen sycomore fig tree (Ficus sycomorus) as opposed to Ficus carica the more familiar fig. The leaves are smaller and oval shaped rather than the large tri-lobed ones of the true fig; the fruit of the sycomore is more rounded in shape. There was an added benefit in that they produce fruit all year round, therefore sycomore trees were often planted near houses, and understandably this species of fig was also an important food for the poor. They are sweet to eat, but before picking them off the tree you needed to make a cut downwards on each one. The sycomore fig is normally sterile in Egypt (it originated further south) but a parasitic wasp tended to burrow into the fruits. This was not such a danger as one might think because the wasps complete the necessary fertilisation of the fig, and notching/cutting the figs would allow the wasps to get out.40 In wall paintings you can often see some of the fruits on the trees have the characteristic slit marks (downwards) on the fruit. Also, in this particular tomb fresco the tree has a female figure inside it; she is the sycomore tree goddess.

FIGURE 24. Ipuy’s house and garden. A gardener uses a shaduf to water the garden. The garden is stocked with a fruiting pomegranate and Sycomore fig, a heavily pruned willow, blue cornflowers and yellow mandrakes, papyrus and white waterlilies/lotus, Tomb of Ipuy, Thebes, 19th Dynasty.

Three other tree species are sometimes depicted in tomb paintings: the acacia, carob and olive. A good example of how the Egyptians depicted carobs is seen in the Tomb of Menena at Thebes (TT69). The fruits are a knobbly elongated pod and are shown like inverted candles on the tree. A seated woman below has gathered some of the fruits into a bowl. She had a young child strapped to her in a sling so that she could work while her child suckled. The pods of the carob (Ceratonia siliqua) are rich in protein, starch and sugar; they are flavourful, and even today are used for animal fodder. It was also a useful plant because it is drought resistant. Ineni, recorded that he had 16 carob trees in what must have been a large garden (or his imagined garden that he could enjoy through eternity). Sadly the fresco of Ineni’s garden is rather fragmentary, there is a small rectangular pool and five rows of trees but the individual traits of these trees are not sufficiently clear to tell which are the trees mentioned in his orchard garden. However, Ineni must have been proud of them to want them recorded in such detail.

In comparison several trees were drawn with care in the wonderful 19th Dynasty fresco of the decorative garden of Ipuy at Thebes (TT217). Gardeners (one accompanied by his pet dog) raise a shaduf from the pools to irrigate the trees and flowers in his garden. To the right of the building behind the white pillar of the shaduf is a flowering pomegranate tree, its distinctive flame coloured flowers stand out. Directly in front of the pillar there are wispy green leaves and stems sprouting up from a heavily pruned willow. There is another pomegranate tree on the far left, then nearby is a persea tree with its small yellow fruits, and a thickly girthed sycomore fig also laden with fruit. Between the trees are a range of flowers, blue flowered cornflowers, red poppies and mandrakes, while in the black lined pools below there are a number of white waterlilies. Close to the building are tall stems of papyrus flowers.

A greater selection of flowers and trees are included in the 18th Dynasty Tomb of Nebamun. The sycomore goddess is present dispensing fruit and drink in the top right hand corner. Here the large trees are treated differently: five carry large yellow fruit bunched in threes, which could identify sycomores; whereas four trees with darker branches and small fruit could represent persea. A wide branched tree in the bottom left corner would be our more familiar fig tree. Many garden frescoes depict trees but relatively few include flowers, other than lotus, however in this fresco (as in the palace scenes at Amarna) there is a flower border surrounding the rectangular pool filled with white waterlilies/lotus, fish and ducks. The flowers form a continuous band, each flower is shown as a many headed clump, but because they were painted onto a dark grey background they are difficult to identify properly. Flowers are coloured blue, red and white (daisy-like).

FIGURE 25. Carob tree represented in the Tomb of Menena, Thebes, 18th Dynasty.

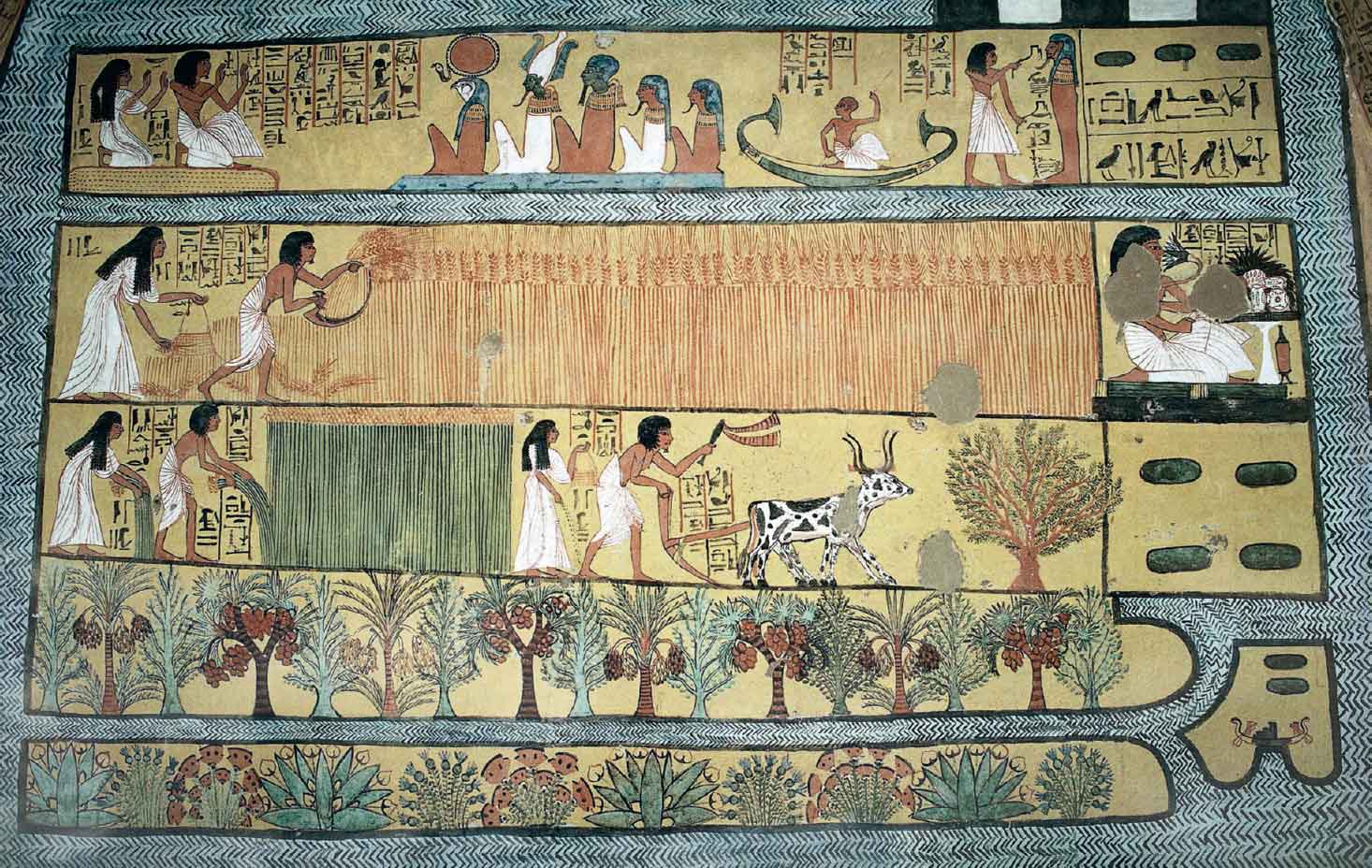

Flowers and trees are portrayed with greater clarity in the Tomb of Sennedjem at Thebes (TT1). The scene is predominantly depicting a cultivated field and irrigation channels. On the third row there is a large willow tree, then below that a row depicting three alternating species of trees (the two main types of palm and a narrow leaved tree, possibly a persea). On the lower register there is a long bed of flowers, they are stylised but identifiable. From left to right they are: mandrakes, identified by their distinctive shaped yellow fruits and strap-like leaves; blue flowered cornflowers, large headed red poppies. These are the most common flowers depicted in Egyptian wall paintings. Less frequently we see the pink flowers of mallow, the white daisy-like flowers of chamomile, a yellow flowered mayweed/chrysanthemum and a plantain-like plant which is thought to be cyperus grass (cyperus esculentus) a popular plant with small edible roots known as tiger nuts.

Some flowers have a special significance, beyond their decorative elements. An indication of the special place that the blue lotus held in Egypt is that it became the symbol of Upper Egypt. The flowering heads of papyrus became the sacred plant and symbol of Lower Egypt. In the charming ivory panel of King Tutankhamun and his wife Ankhsenamun, we see the king and queen sniffing the beautifully scented flowers of blue lotus. Scented flowers were especially admired and you often see images of people holding a choice flower to their nose. Below the royal couple there is a narrow scene showing serving girls picking mandrake fruits, but these are extremely large, much larger than in reality, mainly because they wanted to emphasise that these plants were a highly prized commodity. The mandrake is decorative, but it also holds a special place as a medicine and as a narcotic drug.

FIGURE 26. Nebamun’s fruitful garden, with ducks swimming amongst white lotus in a well stocked fishpond. The pool is surrounded by a border of flowers and trees: Date palms, Persea, sycomore and true fig trees. Restored colours, Tomb of Nebamun, Thebes, 18th Dynasty (© The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved).

Floral bouquets

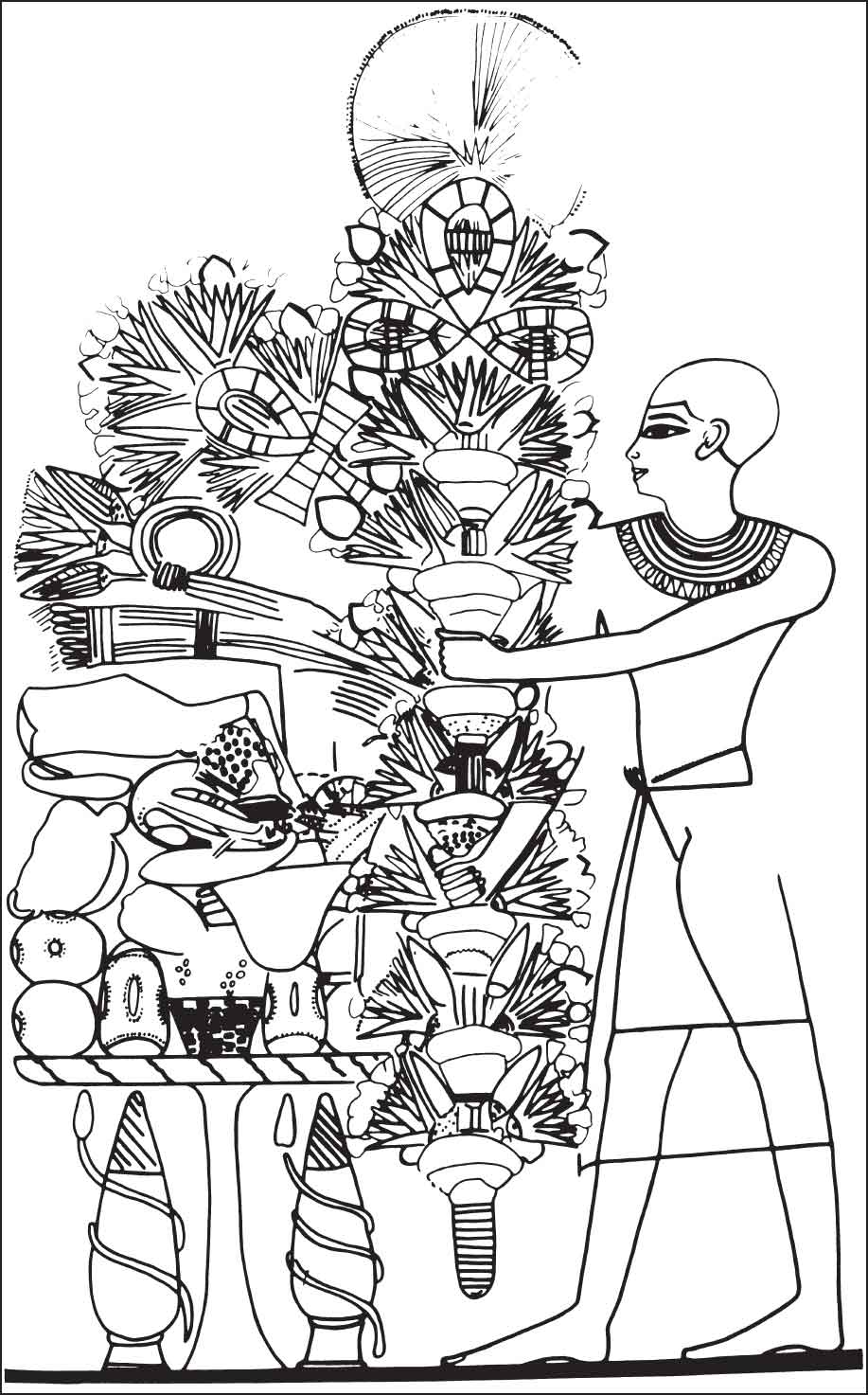

Flowers were used to make floral bouquets, and these are often depicted in tomb paintings. On occasion fruit, such as pomegranates are added to them. Many painted bouquets are quite elaborate and seem to have been fixed into a long slender container, which could be placed into a special holder, or be wedged into the ground to be free standing. Some frescoes capture the moment of making the floral tribute and we see men in the act of adding extra blooms to enhance the effect of their bouquet. Understandably the long stemmed sweet scented blue lotus was a favourite ingredient for these bouquets. Sometimes just a single bloom and two buds of long stemmed lotus are depicted, with their three stems looped together, then placed on to a pile of offerings to the gods or tomb owners. Huge quantities of floral bouquets are recorded as gifts in religious rituals. For instance, Ramesses III offered 1,975,800 bouquets for the god Amun at the god’s sacred Temple (in a 3-year period) and 21,000 were given to honour the god Ptah in the same period.41 This highlights the importance of flowers in this period. Huge quantities of flowers were grown in sacred temple gardens for this. Market gardens would have also catered for the floral requests of the wealthy at court. The most wonderful bouquets are found in the frescoes of the Tomb of Nakht (TT161) who was a court florist, living in the 18th Dynasty at Thebes. Some of his bouquets were huge and multi-tiered, with extra bouquets added for good measure.42 Actual bouquets have been found in tombs, where the dry airless conditions inside has meant that they have survived, but they are very fragile; they crumble to dust very easily. Flower and foliage were used in bouquets and one of the most frequent arrangements found in the tombs is one where a base of persea leaves was used, to which other flowers/plants were added. Two large bouquets with persea were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb.43

FIGURE 27. Irrigation channels provide water for a row of trees and flowers next to a crop of wheat. Three different flowers are represented here, from left to right: yellow mandrake, blue cornflower, and red poppies, Tomb of Sennedjem, Thebes. New Kingdom, Dynasty XIX (De Agostini Picture Library. G. Sioen. The Bridgeman Art Library).

FIGURE 28. Details of flowers painted in the Tomb of Ramesses III, Thebes, 20th Dynasty (after J. G. Wilkinson, The Ancient Egyptians, London, 1854, 365).

FIGURE 29. Nakht, the court florist, with one of his finest bouquets, Tomb of Nakht, Thebes, 18th dynasty.

Flowers grown for floral collars

Floral collars were also made from garden plants, and several are depicted in wall paintings. They were multicoloured and were made of numerous flower petals and leaves, which had to be sewn onto strings and then stitched together. Unbelievably some of these highly ephemeral collars have also survived the millennia in Egypt’s tombs. The one that had been placed around the neck of Tutankhamun’s image on the innermost coffin was particularly well preserved. The range of flowers used in the actual bouquets and wreaths that had been left in the tombs extends the list of known species at that time: Hollyhock (Alcea ficifolia), white mayweed/camomile (anthemis pseudoctula), blue cornflower (Centaurea depressa), golden mayweed (Chrysanthemum cororonarium), convolvulus (Convolvulus arvensis), cordia with a plum-like flower (Cordia gharaf and myxa), pink morning glory (Cressa cretica), delphinium (Delphinium orientale), jasmine (Jasminium sambac or J. grandiflorum), lettuce – the cos type (Lactuca sativa), Madonna lily (Lilium candidum), sweet clover (Melilotus indica), mint (Mentha sativa), persea (Mimusops laurifolia), waterlily (Nymphaea), olive (Olea europea), poppy (Papaver rhoeas and P. somniferum), pomegranate (Punica granatum) and wild celery (Apium graveolens).44 There are perhaps some surprises here, we might think it strange to include convolulus, as it is such a pernicious weed, but we should admit that it does have a nice flower.

Flowers were also used for making perfumes and one of Egypt’s favourites was made from the lily. This would be Lilium candidum the Madonna lily. Lilies are rarely depicted in Egyptian art, however one Late Period tomb relief of the 26th Dynasty shows women carefully gathering the blooms of lilies in what must be a large special bed solely devoted to its culture. They may well have been grown commercially for the bulk that would be needed in perfumery. The rose and narcissus were late introductions into Egypt, under the Ptolemaic Rulers, and as such are out of our scope of this chapter as we are more concerned about plants of the Pharonic times.

There may have been a limited variety of trees and plants grown in Egyptian gardens, but they obviously used them in the best way they could. Many seem to have been placed around the margins of a rectangular pool, which was for practical reasons: you then did not have so far to go to water the plants. An interesting text in the Tomb of Rekhmire (TT100) sums up how much the Egyptians valued their garden flowers. Rekhmire invited guests at his own funerary banquet to take the scented flowers which he had brought for them, from the pick of the plants which were in his own gardens.45 Flowers decorated tables and persons. One of the abiding characteristics of the Egyptians, that highlights just how much they loved their gardens, is that so many Egyptians included a prayer in their tombs so that after death they might be able to return and sit in the shade of their garden and eat the fruit of the trees that they had planted, and be nourished forever by the tree goddess within their garden.

Evidence from archaeology for gardens in Egypt

Few actual gardens have been excavated in Egypt, as modern settlements overly ancient ones. However at the abandoned ancient city of Amarna this is not the case, therefore archaeological work has continued to be undertaken. Beside the Maru-Aten and the painted garden floors of the Great Palace (mentioned above) archaeologists have recently been re-examining the area of the North Palace. In the main inner court they discovered evidence of tree planting, with a row of tree pits on the north side of a large depression that appears to have been a deep open well or pool. Also the slightly sunken area in the open centre of the rectangular Garden Court within the North Palace was found to have been subdivided into a grid of cubit-sized plots with mud ridges (as seen in the reliefs of produce gardens).46 We can imagine these plant beds filled with pleasant flowers and other plants, perhaps to echo the painted walls of the surrounding chambers especially in the ‘Green Room’ that still bore traces of frescoes with palm trees and lush vegetation above a narrow elongated lotus filled pool that formed a frieze across the full width of the room.

These luxuries can be compared with the small garden plots tended by workers and their families in the Workmen’s village at Amarna. Garden areas were small comprising several plant beds filled with alluvial soil brought up from the Nile floodplain. Preliminary work analysing the species of plants that were grown in these beds suggest the following: a variety of herbs, vegetables such as onion, garlic, a variety of cucumis, pomegranate, grape, watermelon, fig, olive, almond and date.47

Palaeobotanical investigations have recently taken place at Amarna, Saqqara and in the Fayum to find the ancient flora of the region. Unfortunately the soil within the Delta area is too moist to allow such a good state of preservation as is found in the dry zones. Data were collected from all the archaeological sites (and from earlier digs) that mentioned the survival of seeds, pollen and macrofossils (remnants of twigs, branches, tree stumps, fruit, pods, flowers, leaves etc.) and was complimented by the quantities of desiccated fruits and floral tributes found in tombs. The information thus gathered was the basis for the Codex of Ancient Egyptian Plant Remains compiled by Vartavan and Amorós.

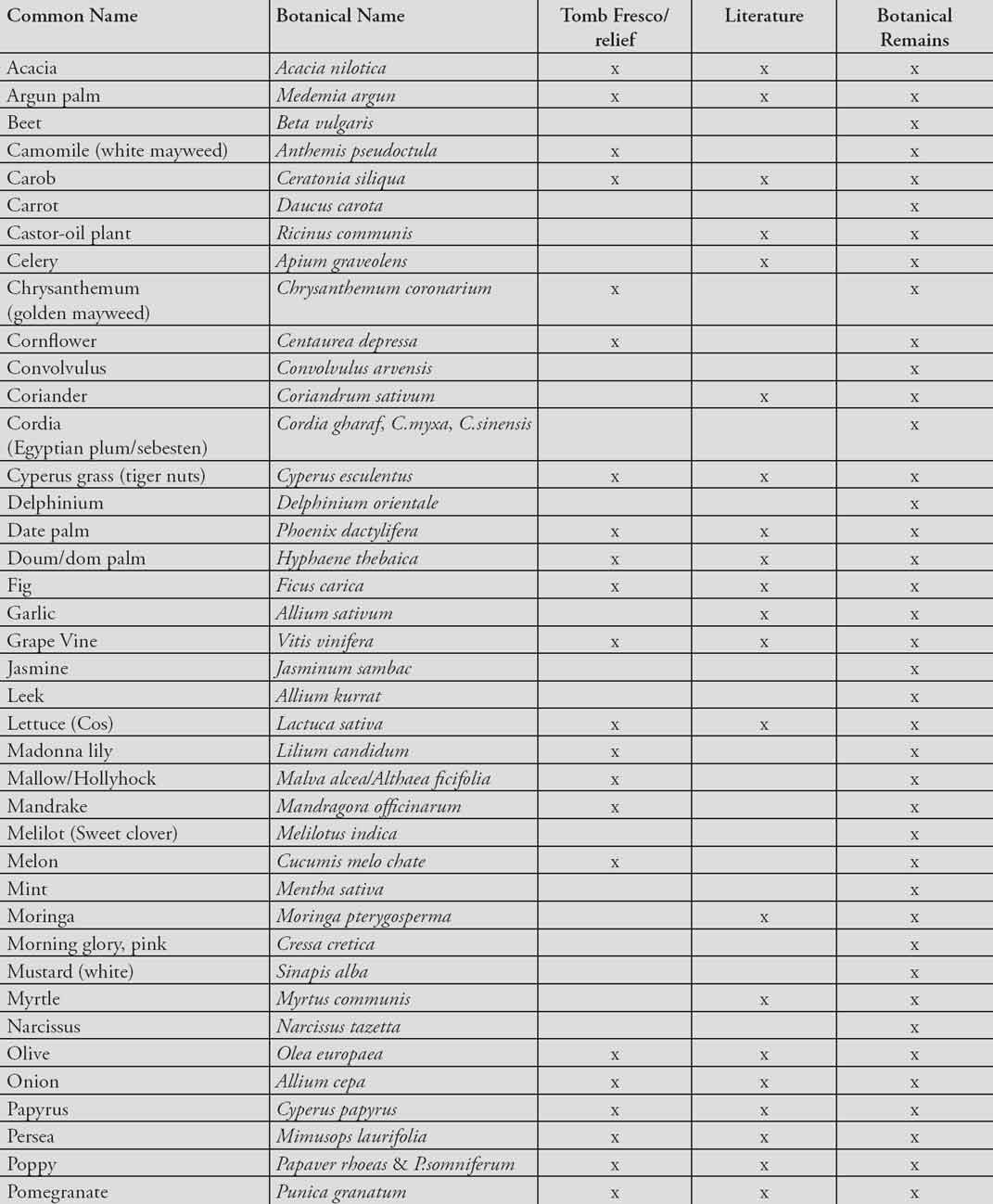

From all the sources pertaining to sacred and domestic gardens mentioned in this chapter I have compiled a list of the species of trees and plants that could have grown within an Egyptian garden. I have included columns listing whether there exists a contemporary illustration of that plant, whether it was mentioned in Egyptian literature (such as in poems, inscriptions or medicinal texts), and if botanical remains were found of that plant species.

Evidence gleaned from excavations and illustrations reveals that over the centuries the form of an Ancient Egyptian garden sees little change. In Egyptian art there is a more fluid style during the Amarna Period, but as far as can be seen the art of gardening during that brief interlude retains the traditional pattern of before.

Ancient texts concerning Egyptian gardens

Literature of this period was primarily discovered within tombs, being either hieroglyphic script written on interior tomb walls and on papyrus, or in hieratic script. Texts are varied, a great number of medical texts have survived, and these indirectly give valuable information on the plants grown in Egypt. The Egyptian pharmacopoeia from the time of Imhotep (the great architect and physician of c.2700 BC) contained about 300 herbal remedies. In later years the number rose to 700 or so remedies. These have been studied recently and the Egyptian Herbal written by Lise Manniche explains the use of 94 species of plants and trees used for medicines, cooking, cosmetics and perfumery, making it a good informative resource.

Some inscriptions mention gardens created by the deceased, but again few describe gardens sufficiently by giving details and layout of planting schemes, but the texts do help to give an understanding of the times, the character of their gardens, and their place in society. Some of these texts also give hints as to the plants you are likely to find in an Egyptian garden. There are also several love poems that have a setting in the garden where trees or an arbour could make an ideal trysting place.

One popular epic, which was set in the period c.1960 BC tells of the adventures of Sinuhe. He was an Egyptian official who went into exile. However, after several adventures he contemplated his life and grew homesick. Luckily he was allowed to return. Towards the end of this epic we learn that after his return he was provided with the customary facilities of court officials:

I was allotted the house of a nobleman … and its garden and its groves of trees were replanted with plants and trees … And the site of a stone pyramid among the pyramids was marked out for me … I acquired land round it. I made a lake for the performance of funerary ceremonies, and the land about it contained gardens, and groves of trees …48

This text supports the concept of how court officials possessed both a domestic garden and a funerary garden, it was expected of them.

The so-called letter of Panbesa describes the city of Piramesse (in the Delta area) that was transformed into a royal residence and court by Ramesses II, thereby giving rare information on garden areas within a city in Lower Egypt:

Its canals are rich in fish, its lakes swarm with birds, its meadows are green with vegetables, there is no end of the lentils; melons with a taste like honey grow in the irrigated fields … Onions and sesame are in the enclosures and the apple-tree blooms. The vine, the almond tree and the fig-tree grow in the gardens … Fruits from the nurseries, flowers from the gardens, birds from the ponds, were dedicated to him [Ramesses] …49

Interestingly we hear that there was a considerable number of people who would have had access to gardens, not just the owners, but the gardener’s family as well, as is revealed in this delightful Egyptian love poem. On this occasion a tree is made to speak and invites the gardener’s daughter under its shade.

Mekhmekh-flowers, my heart inclines towards you,

I shall do for you what it seeks, when I am in your arms …

I am your best girl: I belong to you like an acre of land

which I have planted with flowers and every sweet-smelling grass.

Pleasant is the channel through it which your hand dug out

for refreshing ourselves with the breeze.

A happy place for walking with your hand in my hand …

Hearing your voice is pomegranate wine, for I live to hear it …

The little sycomore, which she planted with her hand, sends forth its words to speak.

The flowers [of its stalks] [are like] an inundation of honey;

beautiful it is, and its branches shine more verdant [than the grass].

It is laden with the ripeness of notched figs, redder than carnelian,

like turquoise its leaves, like grass its bark.

Ita wood is like the colour of green feldspar, its sap like the besbes opiate;

it brings near whoever is not under it, for its shade cools the breeze.

It sends a message by the hand of a girl, the gardener’s daughter;

it makes her hurry to the lady love: come spend a minute among the maidens.

The country celebrates its day.

Below me is an arbour and a hideaway;

my gardeners are joyful like children at the sight of you …

Come spend the day happily, tomorrow and the day after tomorrow, for three days,

seated in my shade …50

It sounds very welcoming there. The tree later says that she is discreet and will not say what she has seen! Sometimes as above the narrator likens his beloved’s features to garden plants, another example is as follows:

Come through the garden, Love, to me.

My love is like each flower that blows;

Tall and straight as a young palm-tree,

And in each cheek a sweet blush-rose.51

A later tomb inscription (c.1400 BC) expresses well the sentiments of those times, the owner wished that he would be able to enjoy these ideals:

[so that] Each day I may walk unceasingly on the banks of my water,

That my soul may repose on the branches of the trees which I planted,

That I may refresh myself under the shadow of my sycomore.52

Notes

1. From personal communication with Dr Joyce Tyldesley.

2. I have used the dates in Shaw, I. and Nicholson, P. British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, London, 1995, 310–311. I have not included the Persian, Ptolemaic or Roman periods as they will be dealt with in later chapters.

3. It is mentioned in the Coffin Texts, Spell 269 (Wilkinson 1998, 117).

4. Respectively: Hepper 1990, 54; Schulz, R. and Seidel, M. (eds) Egypt, the World of the Pharaohs, Könemann, Cologne, 1998, 379, fig. 86.

5. Wilkinson 1994, 3.

6. Wilkinson 1998, 127–8.

7. Wilkinson 1994, 5.

8. Manniche 1999, 121.

9. Stadelmann, R. ‘Pyramiden und Nekropole des Snofre in Dahscher, Dritter Vorbericht über die Grabungen des Deutschen Archäologishchen Instituts in Dahschur’. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 49, 1993, 261.

10. Wilkinson 1998, 68.

11. Wilkinson 1998, 69.

12. Wilkinson 1998, 76–77. Keimer, L. Die Gartenpflanzen im Ägypten 1, Berlin, 1924.

13. Winlock, H. Excavations at Deir el-Bahari, New York, 1942, 6, fig. 1, pl. 68.

14. Wilkinson 1998, 89.

15. Hölscher, U. The Excavation of Medinet Habu, 4, Chicago, 1951, 19.

16. After Breasted, J. H. Ancient Records of Egypt 4, Chicago, 1906, 194–189; Wilkinson 1998, 93.

17. Wilkinson 1998, 149.

18. Wilkinson 1998, 150–151.

19. Lichtheim, M. Literature: A Book of Readings: New Kingdom, vol. 2, Berkeley, 1973, 92.

20. Kemp, B. J. ‘Report on the 1984 Excavations Chapel Group 528–31’. Amarna Reports 2, London 1985, 45.

21. Stevens and Clapham 2014, 160–161; see also Renfrew, J. M., ‘Preliminary Report on the Botanical Remains’. Amarna Reports 2, London, 1985, 175–190.

22. Simpson, W. K. The Literature of Ancient Egypt, Yale, 1973, verse 12.

23. Brewer et al. 1994, 65.

24. Brewer et al. 1994, 65–75.

25. Private communication with Angela Torpey.

26. El-Maenshawy 2012, 58.

27. Wilkinson 1998, 89.

28. El-Maenshawy 2012, 59–60.

29. Manniche 1999, 16; Wilkinson 1998, 136; British Library (Hay MSS 29822, 96).

30. Breasted, J. H. Ancient Records of Egypt 4, Chicago, 1906, 682; Brugsch-Bey, H. History of Egypt Under the Pharaohs, 2, trans. P. Smith, London, 1881, 210–211.

31. Schulz, R. and Seidel, M. (eds) Egypt, the World of the Pharaohs, Könemann, Cologne, 1998, 513 and 516. The exact value today is unknown as the value of silver fluctuates.

32. Gothein 1966, 8; Bellinger 2008, 14; Wilkinson 1998, 25.

33. Gaballa, G. A. ‘Three documents from the reign of Ramesses III,’ Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 59, 1973, 113.

34. Bellinger 2008, 18; Bigelow 2000, 10; Manniche 1999, 10.

35. Wilkinson (1998, 138) identifies other plants in the reliefs of the ‘Botanical Garden’.

36. Gothein 1966, 8.

37. As in the Theban Tombs of Tjanefer and Neferhotep.

38. Weatherhead, F. ‘Painted pavements in the Great Palace at Amarna’, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 78, 1992, 179–194.

39. Brewer et al. 1994, 50.

40. Brewer et al. 1994, 54.

41. Manniche 1999, 24.

42. Manniche 1999, 22.

43. Manniche 1999, 122.

44. Wilkinson 1998, 40.

45. Wilkinson 1998, 105.

46. Amarna Project, the North Palace, Online.

47. Northseatle.edu. Amarna workers village. p. 6; fig. 3.

48. Wallis Budge, E. The Literature of the Ancient Egyptians, London, 1914, 168.

49. Brugsch-Bey, H. History of Egypt Under the Pharaohs, 2. trans. P. Smith, London, 1881, 101.

50. Simpson, W. K. The Literature of Ancient Egypt, Yale, 1973, verses 17–34.

51. Murray, M. A. The Splendour that was Egypt, London, 1977, 210.

52. Gothein 1966, 20.