Gardens of the Greek Bronze Age: Minoan and Mycenaean Cultures

In the Bronze Age period there were two main (but linked) cultures in Greece and its islands: the Minoans and Mycenaeans. The Minoans, who had their capital at Knossos on the Island of Crete, were a maritime people and, besides being in control of the whole of Crete, nearby islands were also under their influence. The Minoans traded with surrounding peoples, and Minoan artefacts have been found in Egypt and at several locations in the eastern Mediterranean. A great deal of evidence comes from Palace sites, such as at Knossos on Crete and also the Minoan town of Akrotiri on Thera (the Island of Santorini). This island is thought to be the unfortunate city in the myth of Atlantis which was destroyed by the cataclysmic eruption of a volcano. Practically all the island exploded, rock and ash was flung far and wide. Earthquakes and huge tsunamis did untold damage which contributed to the decline of the Minoan culture. The date of this eruption has been subject to much research and debate but is now generally accepted to have to have happened around 1600 BC.1 To ease the difficulties of dating, Minoan culture is usually identified by three phases: Early Minoan (EM) 3000–2000 BC, Middle Minoan (MM) 2000–1600 BC, and Late Minoan (LM) 1600–1200 BC. These roughly coincide with the Egyptian Pharonic King Lists (Old, Middle and New Kingdom).

The Mycenaean Civilisation was named after their most important site in Greece, at Mycenae, in the Peloponnese. The Mycenaeans were a more warlike people; they had fortified towns and citadels, but their art and culture was akin to the Minoans. The Mycenaeans are believed to have taken advantage of the destruction of Crete as a result of the volcanic eruption of Santorini, and afterwards Mycenae came into the ascendancy.

Unfortunately the Minoans and Mycenaeans had only a limited system of writing; they had two scripts that we call Linear A and B. Only the latter has been deciphered (by Chadwick and Ventris), but sadly it appears that this script was largely used for inventories of stores in the palaces and no literary texts have been discovered as yet. Recollections of Bronze Age Greece and Crete feature in the Iliad and Odyssey of Homer, works which although written c.750 BC contain many references to their distant past. Groves and gardens are mentioned but, because of the time lapse, they bear more resemblance to features prevalent in the Greek Archaic Period so will be dealt with in the next chapter. Therefore, when searching for evidence of horticulture in Greece and its islands in Minoan and Mycenaean cultures we need to look for other source material, especially at the artefacts they left behind which have been discovered by archaeology. It was found that most garden evidence dates from the Middle and Late Minoan periods.

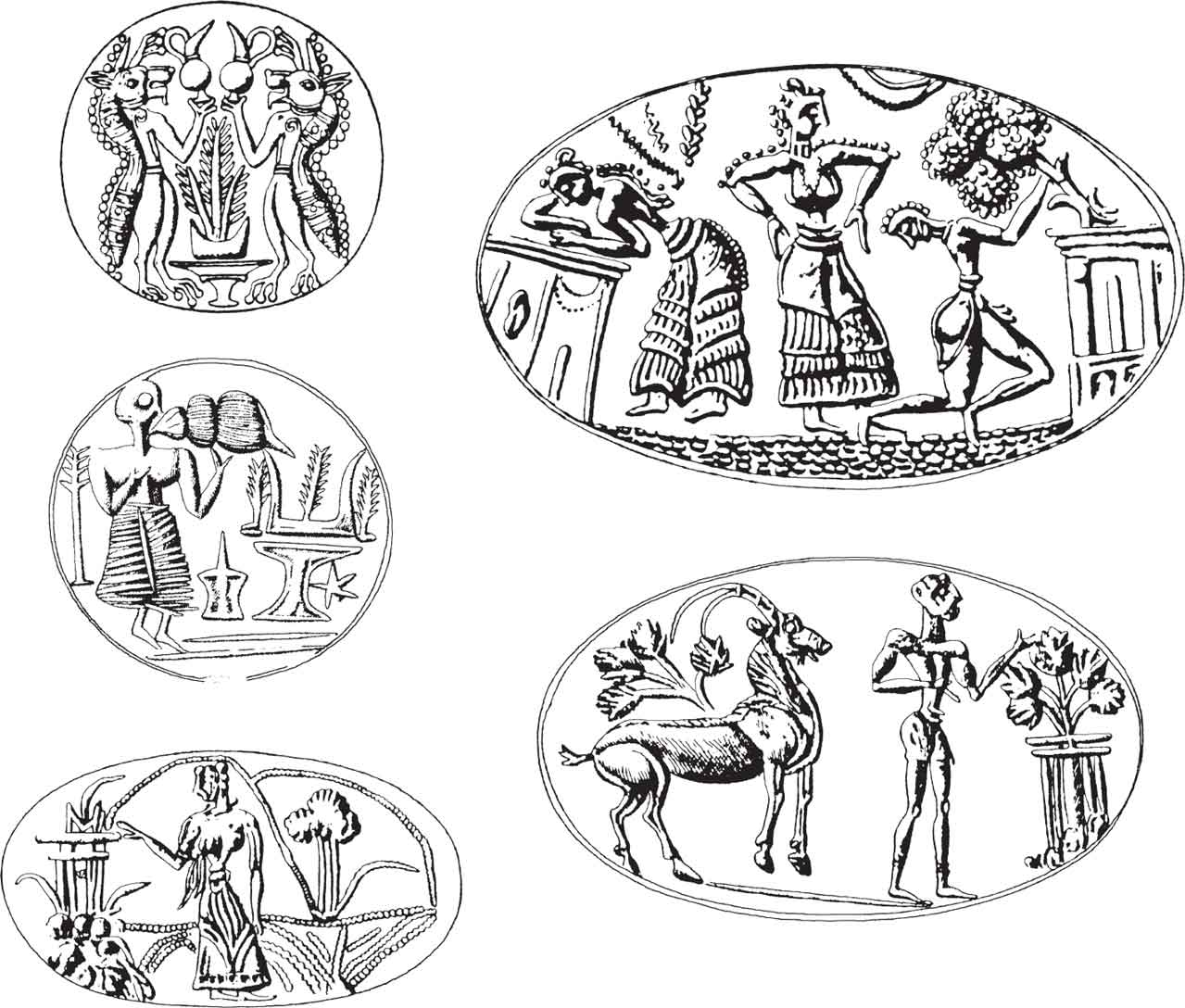

FIGURE 47. Gold Mycenaean seal ring engraved with a scene depicting the great Mother goddess sitting under a tree, holding poppies. Attendants bring her more flowers, 15th–14th century BC, Athens Museum.

Sacred trees and a tree goddess

Archaeological evidence shows that the Minoans had a deep love of nature, because we see flowers and trees used frequently as decorative motifs. We can also see that there must have been a veneration of sacred trees. A sketchy sacred tree is shown on both the long panels of the painted chest from Haghia Triada in Crete (LM c.1400 BC). On one panel the tree stands next to a shrine. A priest or the deceased stands at the entrance, and worshippers arrive bearing gifts, while on the opposite side a slightly better defined tree appears to be growing inside the shrine or behind it. A fragmentary Theran fresco also shows a tree next to a shrine;2 the closely spaced leaves indicate that it may have been an olive tree. Sacred trees feature on a number of seal stones from rings found on Crete, and at some Mycenaean sites showing that the cult was quite widespread in the Middle and Late Minoan period.3 Many seal stones also show a mother goddess and her worshipers next to trees, these may possibly indicate that she was a particular fertility goddess called Eileithyia who is named on several Linear B tablets.4

FIGURE 48. Impressions from seal rings with scenes of a tree cult.

A beautiful gold ring found at Mycenae depicts the goddess sitting under a tree, the pattern of leaves indicates that this is possibly a terebinth tree which was considered as having sacred powers. Resin from this tree was seen to have healing abilities and purification properties.5 On this ring attendants present the goddess with poppies, irises and other flowers, while another attendant tends the tree. The all important sun and moon (to indicate the realms of day and night) are present in the sky above. Another seal stone from Mycenae features a man giving homage to a tree enclosed by a protective surround. Two other seal stones depict three tree branches or plant stems on top of an altar, which is in some ways reminiscent of the three-leaved symbolic depiction of the Egyptian God Min. This could imply a similar need for an agricultural/horticultural fertility deity. A carved crystal stone found in the Idaean Cave Sanctuary (central Crete) shows one attendant using a giant sized conch shell to pour a libation upon the symbolic triple tree branches. Whereas, in the example from Vapheio in Greece, a pair of mythical beasts use flagons to give a libation.

Plants depicted on Minoan ceramic vessels

One of the distinctive features of Middle and Late Minoan ceramic vessels is their use of decorative spirals, rosettes and schematic floral designs showing a variety of plants. Several portray foliage or twigs of shrubs and some display different forms of grass-like stems or reeds, some of which are flowering. The opposite paired pattern of some leaves resemble myrtle or olive. The rosettes could represent a rose-like flower, which may be either a dog rose or a rock rose (perhaps Cistus creticus which is still common on the island). Many plants are rather stylised, and not all are identifiable, but those that can be distinguished are: caper, crocus, a daisy-like flower, ivy, lilies, palm trees and vines (more specifically bunches of grapes). The climate in the Bronze Age is generally thought to have been wetter than it is today,6 so the range of plant species on Crete and the Greek islands could well have been greater in the past. Therefore it is difficult to specify particular flowering plants today. Two examples are the appearance of a distinctive looking flowering plant on a vase from Thera which looks similar to a white helleborine, and a nodding solitary flower that may represent a form of wild fritillary which appears on a jug from Phylakope; these could be plants that are now extinct in Crete or are varieties that have continued to evolve over the centuries.

A bowl from Thera was found to depict ‘a remarkably faithful picture of one of the three Cretan species of Tulip, namely Tulipa cretica’ this plant was accompanied by a form of ‘Ranunculus asiaticus’.7 The countryside of Crete abounds in wild flowers and herbs and it is no surprise that this great abundance would be reflected in their art. But by far, the most frequent floral subjects are lilies and crocus. These two flowers must have held great significance for the Minoans, and they may even have become sacred, the reasons for this will be discussed later.

FIGURE 49. A selection of flower motifs on Minoan pottery.

Some of the painted jugs and vases are decorated with a single species of plant; often the depiction is bold and vigorous. An example is a vase from Thera which has lily plants springing from a broad band at the base; each lily sprouts three flowers, one facing upwards in the centre and one on either side leaning outwards. They were painted in white on a dark background to make them stand out more clearly. An elegant tall vase from Knossos again depicts lilies but in this case there are four lily flowers at the upper part of each stem with three flower buds yet to open at the top. Strap-like leaves are shown at the base. These differing modes of depiction could indicate two different species of lily.

An interesting range of flowering plants were displayed on one vessel discovered in a LM tomb, at Chamalevri on Crete. The lid was decorated with a horizontal band of stylised lilies, and on the body of the vessel there were groups of papyrus, lilies, crocus and caper, then an unidentifiable herb on its base.

Plant containers

A shallow dish-like plant container features as a small motif picked out in gold on a silver goblet found at Mycenae. Growing out of the container are five stems with closely spaced opposite leaves, and the terminal flower on each stem appears somewhat akin to a daisy or chamomile. On either side of the container there are groups of strap shaped leaves indicating secondary leaves or different plants. Sadly, the plants in question are generalised and their identity can only be guessed at. Another shallow dish can be seen in a fragmentary fresco from Knossos (the Saffron Gatherer) which contains flowering crocus plants. The bowl appears to be ceramic and has looped handles. These small details provide evidence of a form of gardening; for tending plants is the first step to horticulture. This is corroborated by finding some pots with a hole in their base at Knossos and Mallia, which are thought to be flowerpots.

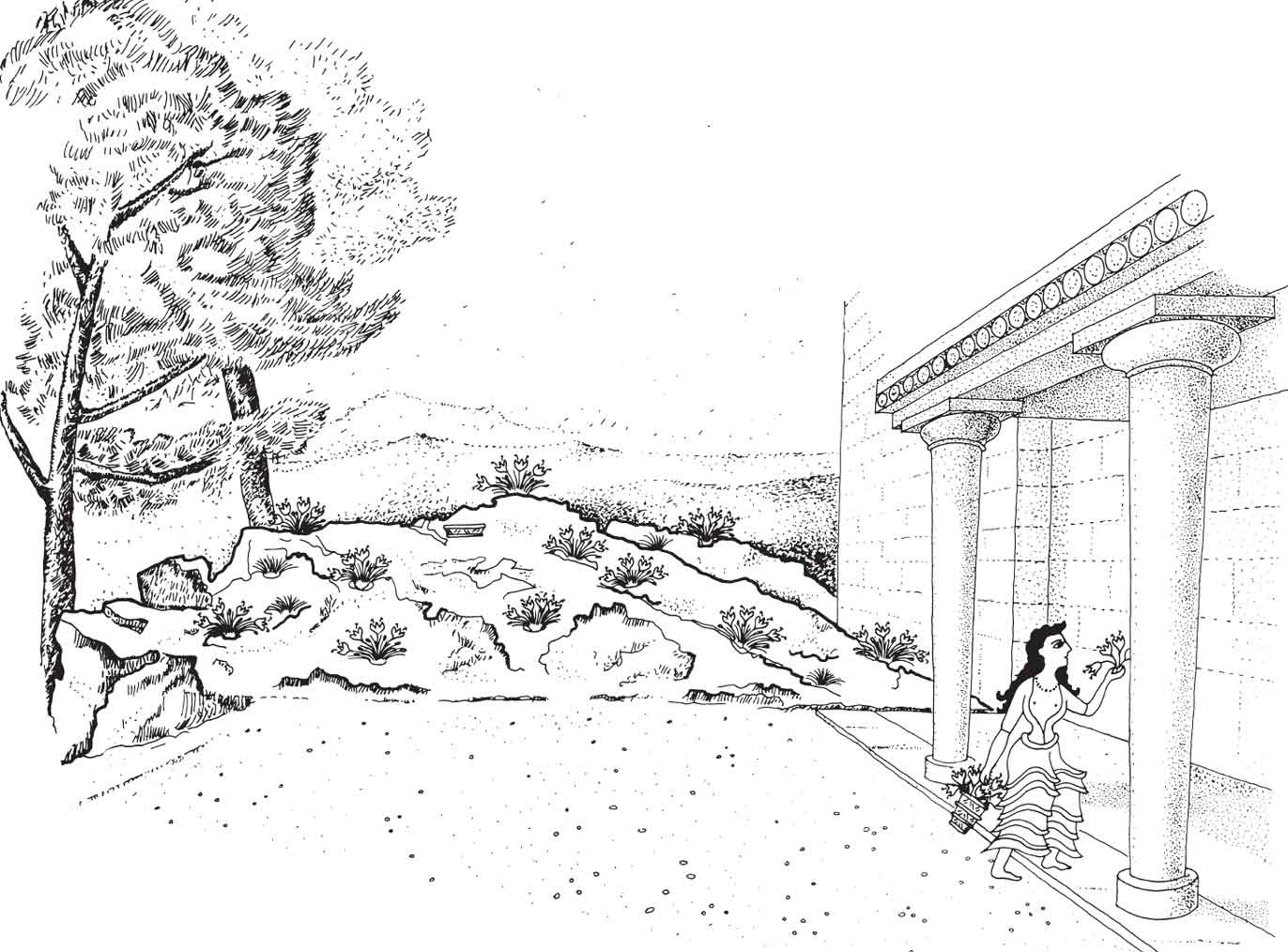

FIGURE 50. Drawing of lilies in a slender banded vase. One of a pair, painted on frescoed window jambs. The next best thing to having real flowers on your window sill, from Akrotiri/Thera, Santorini.

FIGURE 51. Silver goblet from Mycenae with a gold motif depicting a plant growing in a shallow container.

Interestingly, two small Theran frescoes, on either side of a window jamb of a townhouse, were painted with a realistic rendition of tall stems of red coloured lilies in a banded vase. The lilies may have represented cut flowers placed into the vase, but they could equally have been planted in the pot specifically to add a bit of colour and nature in the house, where they could remind the owner of the joys of the countryside or garden.

Plants in Minoan frescoes

The flowers that can be identified in Minoan frescoes are: crocus, lily, iris, rose, dianthus-like flowers (from Hagia Triada), and large yellow and white flowers that appear similar to an oxeye daisy which may be Chrysanthemum coronarium var.discolor (found in the Unexplored Mansion at Knossos). Of this group of flowers the most frequently painted ones are again the lily and crocus.

There is a hauntingly beautiful fresco (the so-called ‘Spring landscape’ from Thera) that depicts a very rocky ground from which clumps of red lilies grow, while swallows fly acrobatically above. The fantastic rocky landscape though is not mere imagination as some people believe but resembles an area just one kilometre to the west of the excavations at Thera. The artist’s free style had a basis of truth, and he wanted to convey his delight in his own surroundings. The frequent depiction of the Lily is not only because of their elegant beauty, the flowers only last a few weeks, but because they have such a fabulous memorable scent.

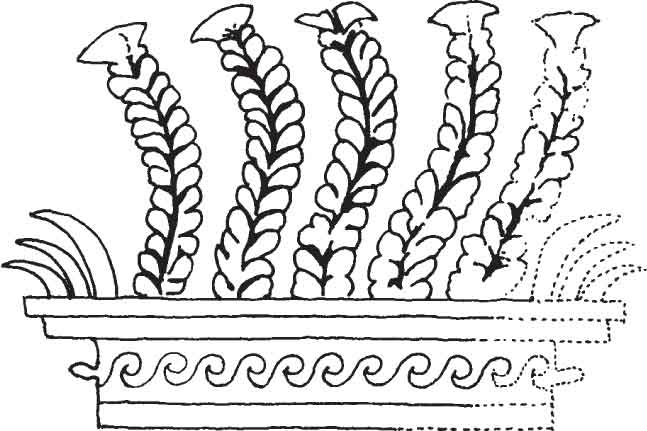

Two different species of lily (sometimes identified as iris)8 were painted on the walls of room 7 at a large villa/palace at Amnisos on Crete (dated to c.1600–1500 BC; see Fig. 50). Here the larger than life size representations of lilies dominate the walls. One wall featured white lilies, set off against a red background; these would be representative of the Madonna Lily (Lilium candidum). Another wall showed red flowering lilies which are thought to be Lilium martagon the so-called Turk’s Cap lily, or possibly L. chalcedonicum. The red lilies were interspersed with a non-flowering bush or herb (that may be mint),9 but both of these appear to have been planted into a wide planter with incurved sides, showing that these beautiful flowering plants had now become cultivated and must have belonged to a garden area.

FIGURE 52. Reconstruction by M. Cameron showing the lily frescoes in Room 7 at Amnisos, Crete, (reproduced with permission of the British School at Athens)

FIGURE 53. Sand lilies on the Island of Santorini.

FIGURE 54. Fresco fragment showing dianthus-like flowers, from Hagia Triada.

The Minoan frescoes display a greater range of flora than can be seen on their ceramics. Frescoes from Crete are displayed in the Archaeological Museum at Herakleion. Theran frescoes (from the archaeological site of Akrotiri on the island of Santorini) are displayed in the National Archaeological Museum at Athens. Among the plants illustrated newly discovered fragments from Knossos show sprays of olive.10 Vines feature in another fresco from Knossos, ivy at Hagia Triada, pine and palm trees at Thera.11 Several frescoes portray reeds or sedges, which are thought to be either the galingale or Cyperus esculentus which is known to have been cultivated for its edible tubers (tiger nuts). It is often shown flowering, so too are fronds and umbels of papyrus. The latter however is not believed to have been a native plant, and may be represented in Minoan art because of its exotic qualities and associations with Egypt where it grows abundantly in the wet areas of the Nile Delta. Papyrus, the paper reed, is thought to feature in the large fresco found in the House of the Ladies at Thera. These plants are large and their representation matches this, but because these flowers have a series of kidney shaped dots above each flower umbel they could represent anthers on stamens which papyrus do not possess. Therefore, it is now believed that they may in fact represent the smaller native sand lily/sea daffodil Pancratium maritimum.12 Perhaps the artist had not seen a papyrus plant before and based this image on his more familiar native lily. Another important flowering plant of Crete is the iris (Iris cretica) its slender leaves and flowers are faithfully rendered in two frescoes from the House of Frescoes at Knossos, where their flowers were painted blue.

Some of the roses depicted in Minoan frescoes show an open flower and therefore there is some ambiguity as to whether it depicts a true rose or the rock rose. However the so-called ‘Blue Bird’ fresco from Knossos depicts what must be a true rose flower, with its distinctive leaves and buds; this image is the earliest representation of a rose in Europe.13

A wonderful fresco from Knossos depicts a series of circular flower garlands in a frieze that may have originally run along the top part of a wall. Every garland had decorative strings tied into a bow at the top, with the remainder of the long strings left to dangle like a pendulum. Each garland is composed of one particular species of flower making them unique. The flower species represented in this instance appear to be of: crocus, lily, myrtle, olive, rose or rock rose, and a dark red flower that could be either an anemone or a red ranunculus asiaticus.14 The care taken in the portrayal of each garland is remarkable and is a sign that the Minoans sought to beautify their houses as well as their person.

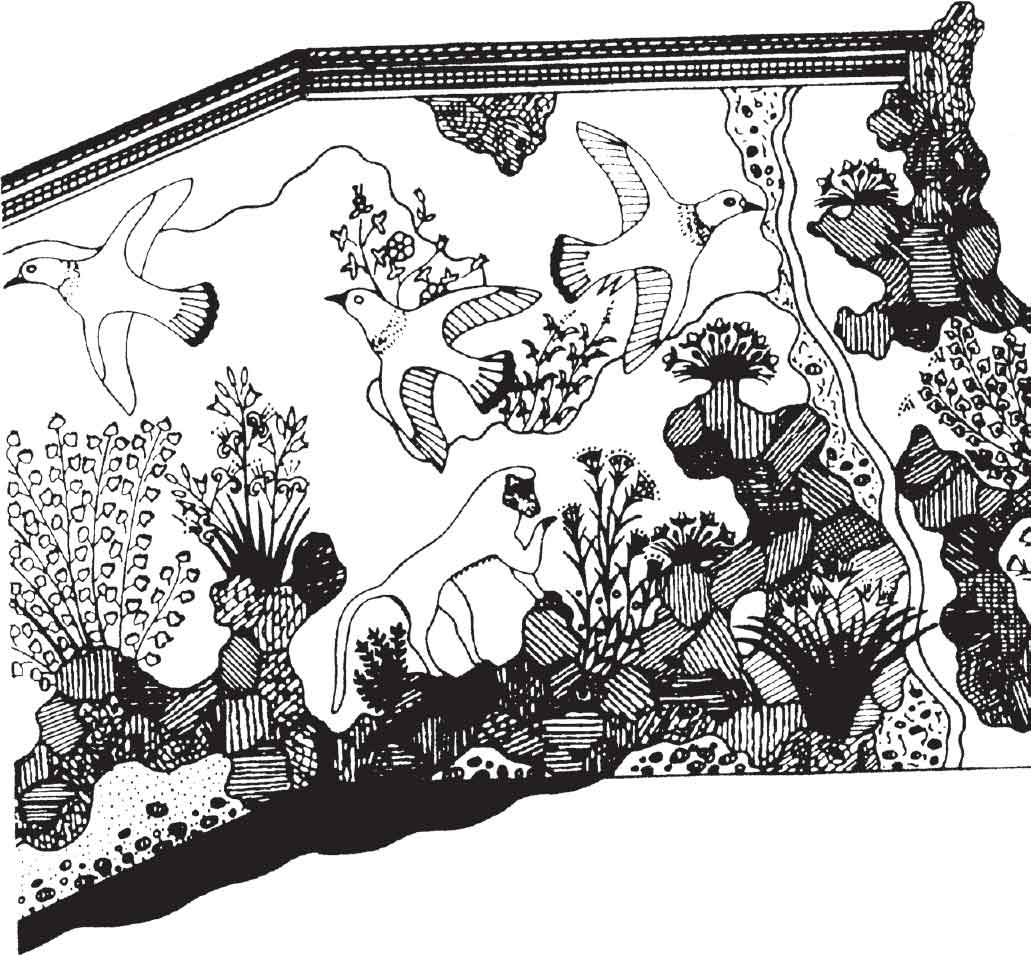

Some of the frescoes form a continuous miniature landscape with a little stream running throughout the length of the frieze, as in the ‘nilotic scene’ in the West House on Thera. The plants may at first glance be thought as wild ones in the countryside, but the plants are often small (such as the dwarf palms) and could imply a managed and well tended landscape. Palms are propagated by transplanting suckers from an adult palm, mostly from a female palm, and the stream nearby would supply the necessary water for these newly planted saplings. Sometimes monkeys are shown in these frescoes. Monkeys were imported into the Aegean areas as exotic pets, they were not native animals, and therefore they would have only been allowed to roam in controlled areas. This would then suggest that the area was a form of park or landscaped garden.15 The scenes are captivating, and were freely drawn. Birds and other animals are shown in the foliage of these lively frescoes. In one section a cat chases a duck by a little stream surrounded by sand lilies and young palms.

FIGURE 55. Top row, l to r: lily, myrtle, ?, olive; Bottom row, l to r: anemone/ranunculus, rock rose/dog rose and crocus, Knossos (redrawn from J. Clarke in Morgan, 2005).

FIGURE 56. Detail from a Minoan fresco depicting a garden landscape with tame monkeys. House of the Frescoes, Knossos, (after M. Cameron in Shaw 1993, 669).

The second most popular plant was the crocus. Minoans painters had a limited colour palate therefore some of the identifications of plants are not as clear as we would like and we find that most crocus flowers are painted in a maroon red colour which is meant to represent the purple flowers of Crocus cartwrightianus or Crocus sativus the saffron crocus.16 Each has two-four prominent bright orange stamens. However, in some cases the crocus-like flowers are painted blue, and these may imply a flower of the campanula family,17 perhaps Symphyandra cretica or trachelium asperuloides. Several frescoes found at Knossos and on Thera suggest that the Minoans cultivated and picked saffron from their crocus plants. One fresco of particular note shows the procedure. One wall in Room 3, Xeste 3 at Thera, shows two girls in a crocus filled landscape picking the flowers with their valuable stamens, in their other hand they carry a basket with looped handles. On two other walls a girl carries a filled basket on her shoulder, while another empties the basket into a much larger wicker basket. At this point you can clearly see that the whole flower was picked, not just the stamens. In the centre of this tableau a large monkey presents a sample of their produce to a giant sized seated mother goddess figure. The regal status of the goddess is highlighted by her greater size and by a royal griffin at her side. The presence of the monkey may seem strange, but at Knossos a fragmentary fresco depicts what some believe to be monkeys picking saffron crocus. It is possible that the Minoans trained monkeys to do this back breaking job. In both frescoes mentioned crocus are shown growing on rocks. In the Theran example they are also shown as a repeat pattern in the background to imply wide spread cultivation.

FIGURE 57. Circular enclosure with two trees (perhaps representative of more) that indicates what could be an orchard. Detail from a Theran fresco of city and seascape scenes, from Room 5 of the West House, 15th century BC.

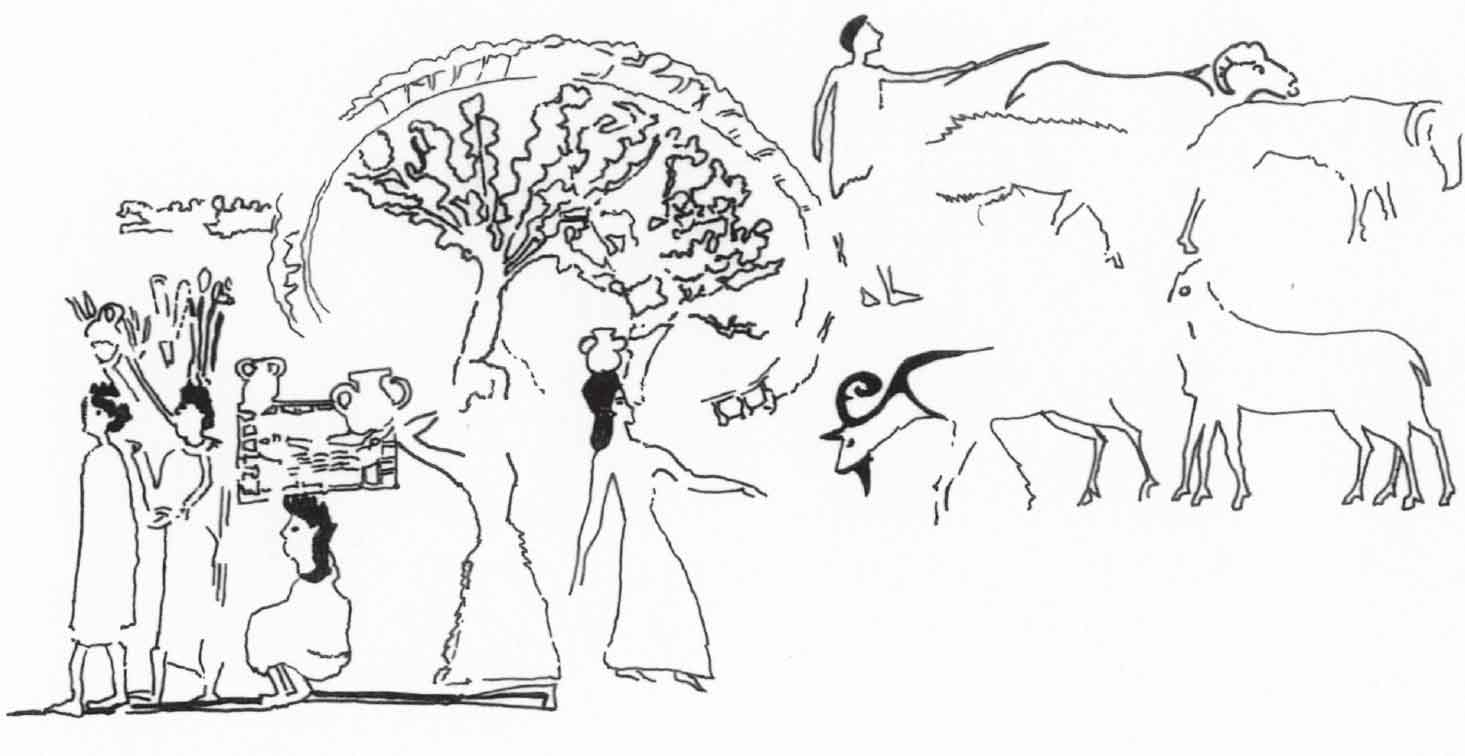

Depictions of an enclosure garden

In Room 5 of the West House on Thera, within the long frieze depicting city and seascape themes, there is a painted detail that features a circular fenced enclosure surrounding two trees. This enclosure appears to be an orchard, as the two trees could be representative of more. The scene is close to a building/house and nearby (to the right) grazing animals are being tended. Their proximity suggests that the fenced enclosure would keep livestock away from precious trees. This section of the fresco therefore shows aspects of Theran life: animal husbandry and horticulture.

Another ‘garden’ appears on a gold disc shaped seal from Poros.18 Here a tree with three distinct branches is shown behind a crenelated wall made of coursed brick or stone. Interestingly a large dog is positioned between the wall and the tree, as if it was guarding the garden. The stepped wall shown here is reminiscent of the plain white wall seen behind white lily plants in the aforementioned fresco of the lilies from Amnisos.

FIGURE 58. Reconstruction drawing suggesting a rock garden for crocus and other plants, in the Palace at Phaistos, Crete, 15th century BC (M. C. Shaw and G. Bianco in Shaw 1993, fig. 23).

Two thick-girthed large trees feature in a miniature fresco from Knossos that is thought to represent a sacred grove.19 The tree species cannot be identified but as this grove is close to an entertainment area they may in fact have been planted there as shade trees. A wall (or pathway seen from above) separates this grove from a group of dancers watched by quite a crowd. Another walled grove is suggested on the fragment of a serpentine rhyton drinking vessel from Knossos, again the wall marks the limit between the grove and a recreation area. The tall mature tree has large leaves that are dissected into three, it is believed to represent a fig tree (Ficus carica).20

The Minoans are believed to have cultivated fruit trees, such as quinces and pears, presumably in orchards. The botanical name for quince (Cydonia oblongata) provides a clue because the ancient Greek word for quince is Kydonia.21 The fruit was actually named after a Cretan town Kydonia (modern Khania) which appears on the Minoan Linear B tablets as Kudonija. The fertile plain around this town is still a good fruit producing area. Seeds of pear/apple were discovered by archaeologists at Kommos, along with almond, fig, olive and carob that may have grown in cultivated areas near the town.22 Tablets found at Knossos mention trees of the Pistachia family, perhaps indicating that they too grew in Crete at that date.23

Archaeological discoveries of gardens

Recent archaeological research has now actually provided evidence that suggests crocus were grown in gardens. At the Palace of Phaistos in central Crete an hitherto unidentified garden area was discovered, where one portion had been turned into a rock garden for crocus plants (see Fig. 56).24 This garden would have brought their favourite plants close to the home, where they would have extra care, the owner would enjoy the sight of them in flower and still be able to harvest the saffron and extra corms they might make. The mass of crocus would have been a wonderful sight. The rocks were cleared of soil and numerous depressions were noted which could have been sufficient for planting bulbs or corms. The holes were roughly circular and 10–30 cm wide and 6–10 cm deep; some of the holes shelved which would have helped drainage, although the rocks here tend to be porous.25

Other palaces may have had garden areas and/or orchards or groves; an orchard has been suggested in an area south-east of the palace at Zakros, and a possible grove may have existed to the south of Hagia Triada (both on Crete). Residential quarters in a palace are often located close to a series of doorways or columns akin to a loggia opening onto garden terraces.26 Archaeologists found one of these on the north-western edge of the Palace at Mallia, on the northern coast of Crete. The garden here was roughly rectangular with a pillared loggia on one side giving access into the area. However, when it was excavated no paleobotanic record was taken, so we do not know which plants originally grew there. However, Mallia is known as the findspot for a strikingly beautiful gold pendant of a pair of bees. The island is well known for its honey production even today, and Minoan pottery beehives have been discovered. One can make a conjecture that cultivated herbs and plants from this garden were utilised to make honey at Minoan Mallia, as well as the profusion of wildflowers in the Cretan countryside.

The fluctuating climate of Greece and its islands does not favour the preservation of paleobotanical specimens (unlike Egypt where the dry air desiccates remains), and little garden archaeology has taken place. However at Akrotiri, in the areas sealed by the eruption of Santorini some evidence has been unearthed, such as a stump of an oak tree within the ancient settlement.27 Such a large tree would have provided ample shade below its canopy.

Evidence for vegetable gardening has come to light through recent scientific studies on the residues left behind inside Minoan and Mycenaean ceramic vessels (cooking pots, drinking vessels, storage jars, etc.). Waxes and oils are secreted by some plants and after time in storage, or as a result of cooking, the waxes and oils had been absorbed by the unglazed inner walls of these pots. Valuable evidence can be found on the former contents of individual vessels, which in turn informs on the diet of people in this period. An analysis of these residues shows that some vessels once contained liquids (e.g. from drinking cups and jugs and amphorae) whereas some of the cooking pots indicated that a combination of ingredients were being cooked together (or on separate occasions each leaving a trace). We now know that vegetables and sometimes fruit formed ingredients cooked in a form of stew, occasionally with meat. It appears that copious amounts of olive oil was commonly used in Minoan and Mycenaean recipes, and that a wine flavoured with resin was appreciated as far back as Early Minoan Crete.28 Some residues however can only be identified as ‘waxes from fruit and leafy vegetables.’29 Of these vegetables there are indications that a form of sweet courgette was being consumed at Apodoulou,30 but identifying multiple ingredients in a specific pot proves very difficult. However, in other cases the researchers can be more specific, and plant residues include almond, fig, grape, olive, pear, and possibly apple, lentils, chick pea, grass pea, and faba bean, the last of which requires constant watering that implies horticulture. These would indicate that the plants to produce these results were growing nearby.

Some of cooking pots were found to have contained resinated wine with the addition of one or more aromatic herbs, showing that at times the Minoans took what may have been a medicinal or ritual brew.31 The herbs used in these cases were: laurel, lavender and sage, one cooking pot even had wine with rue which would act as a stimulant.32 The natural sweetener honey has been assumed from traces of beeswax found in a few jars and bowls used for storage. Apparently honey, or a honey mead, was also added to make a fermented beverage comprising wine; such a ‘honeyed wine’ is mentioned on the Linear B tablets.33 Honey was even added to a barley beer, and on occasion to make a brew with wine, honey and beer all together!34

In some cases evidence of flowering plants were found by the analysis of residues, and on one remarkable occasion residues of oil of iris had survived inside a small pot from Armenoi on Crete (LM).35 This rare find is evidence of the importance of iris in the Minoan period and of the production of perfumery. Oil of Iris is made from the root of the plant and today it is the most expensive ingredient in perfumes. So we can appreciate the importance of this plant to the Minoan economy, both for home use and for export.

Botanical references on Linear B tablets

Sadly there is no Minoan equivalent to the Egyptian/Assyrian herbals. The only clue to the practise of medicine and the culture of medicinal plants is found in a Linear B text mentioning the word pamako, which is similar to the Greek word for pharmacy. Chadwick and Ventris found that Linear B words bore some similarities to archaic Greek, and this really helped to decipher the language and script. Few Linear B texts mention flowers though, but there are references to: poppies, roses, saffron (crocus), safflower and hibiscus. The ancient hibiscus is not the shrub we know today but is likely to be a tree mallow or Althea officinalis the marsh mallow. The ancient name for iris, which was so prized, has not been identified yet, but it is suspected to be the root called wi-ri-za that is always accompanied by an ideogram implying it needed straining – for perfumery.36 Apart from medicinal and perfumery, garden herbs were also used in Minoan and Mycenaean cooking; one of the most frequently mentioned herbs in the Linear B tablets was coriander. In palace inventories at Mycenaean Pylos, it was called Koriadnon which again is very close to our present word for this herb. Large quantities of coriander were recorded at Pylos, around 576 litres.37 Other herbs mentioned in the tablets are celery, cress, cumin, fennel, mint/pennyroyal and sesame.38

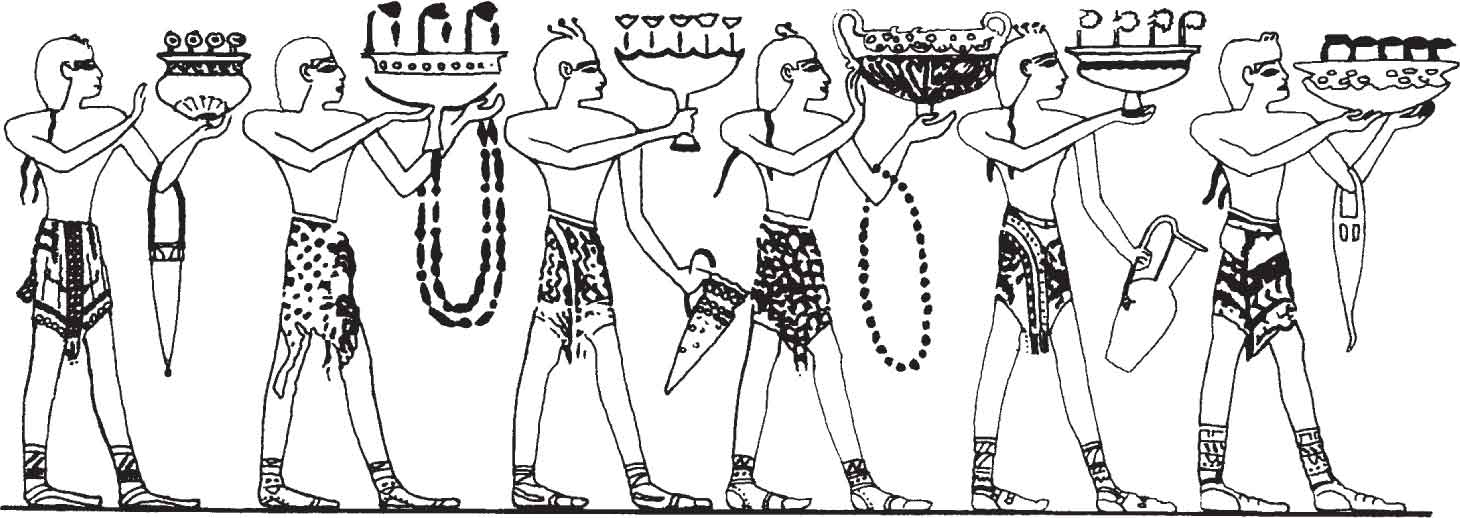

FIGURE 59. Details of men from Keftiu (the Egyptian name for Crete) taken from an Ancient Egyptian fresco of foreign vassals or traders carrying their respective goods/tribute. This selection highlights Minoans carrying herbs or precious aromatic plants in their distinctive pottery vases, 15th century BC. Tomb of Rechmire, Thebes.

Tablets, and archaeology, have shown that medicinal plants were gathered and prepared in Crete and Mycenae. It is also clear that exports of medicinal and aromatic plants were made to Egypt, although it is uncertain if they were traded or were a form of tribute. This scenario is seen to good effect in an ancient Egyptian fresco, from the Theban Tomb of Rechmire (15th century BC), which records an instant when tribute was brought to Egypt by foreign nations. Included in this documentary fresco is a line of men from Keftiu (the Egyptian name for Crete) carrying their distinctive pottery vessels. Some of the wider vases are filled with very stylised flowering plants, four different species are represented here, but sadly they are not named. The produce from Keftiu is stacked up at the end of the line while a scribe notes them all down. Iris, lilies and saffron crocus may well have been items sent to Egypt, and because of their great value they would have been treated with extra care, the Cretans perhaps even accorded them sacred qualities, and as we have seen they are frequently depicted in their art. Interestingly there are Egyptian texts referring to special ‘Beans from Keftiu’, which were evidently imported for medicinal purposes, apparently they were useful to clear out blockages.39

Evidence from Minoan pottery and frescoes both point to a deep love of nature. Flowering plants held a special place in their hearts and minds, especially lilies and crocus. The Cretans utilised their abundant wealth of wild and cultivated flowers and herbs. The mountains of Crete are still covered with aromatic herbs, which make it a botanist’s paradise. But it is noticeable that the plants depicted in Minoan frescoes are in the main cultivated garden species not wild ones.

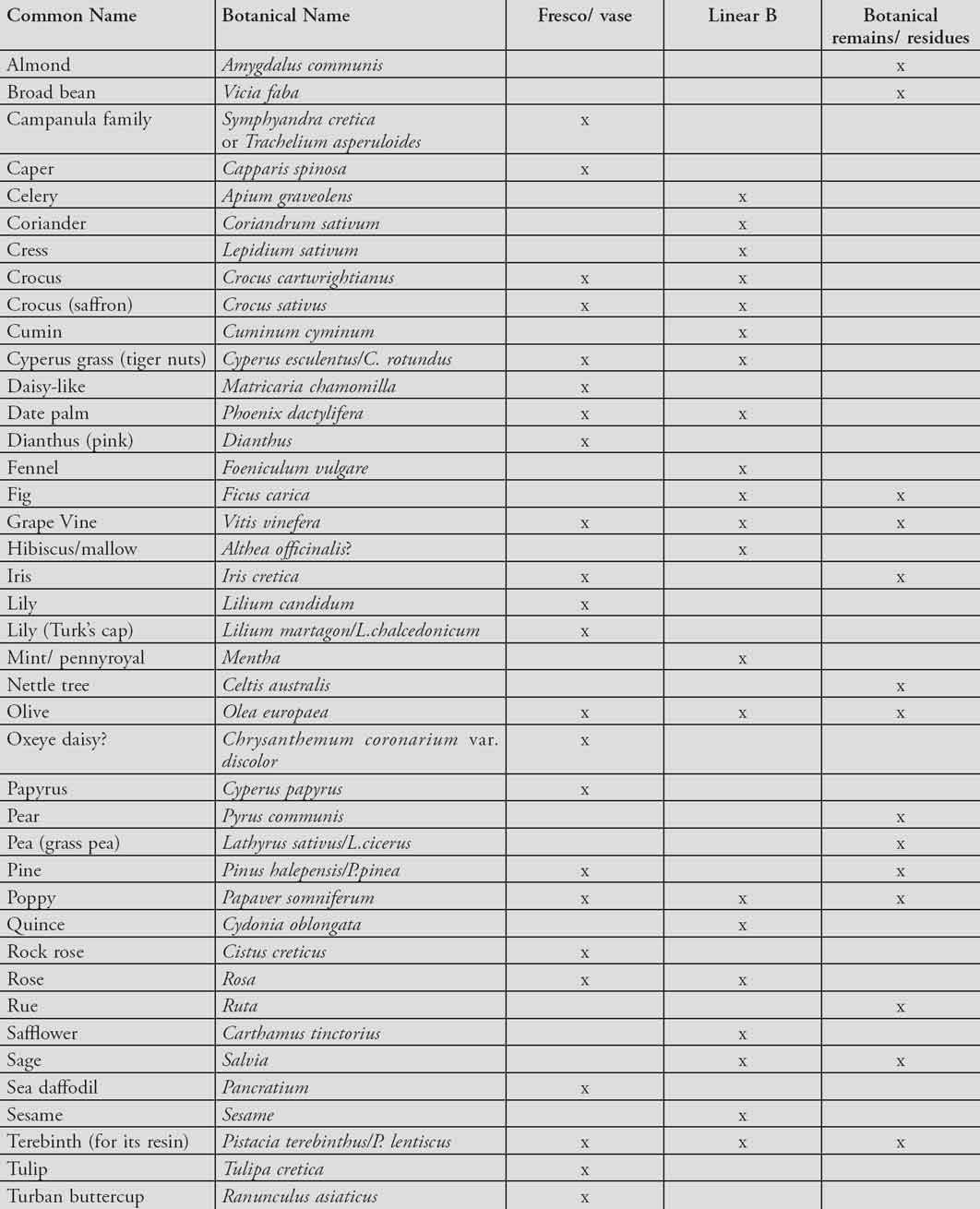

Botanical remains/residues are listed in the table of known garden plants for the Greek Bronze Age. Two separate columns indicate if the plant was illustrated and/or was mentioned in Linear B tablets.

1. See Manning, S., A Test of Time and a Test of Time Revisited, Oxford, 2015, for the latest discussion.

2. On the East Wall of Room 3a, Xeste 3, Akrotiri (Vlachopoulos, A. ‘The Wall Paintings from Xeste 3 Building at Akrotiri: Towards an Interpretation of the Iconographic Programme’, in Brodie, N. et al. Horizon: A Colloquim on the Prehistory of the Cyclades, Cambridge, 2008. fig. 41.10).

3. Evans 1901, 99–204; Krzyszkowska, O. ‘Impressions of the natural world: landscape in Aegean glyptic,’ in Krzyszkowska, O. (ed.) Cretan Offerings, Athens, 2010, 178–184.

4. Castleden, R. Life in Bronze Age Crete, London, 1990, 51; Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 266.

5. Beckmann, S. ‘Terebinth in Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age Crete,’ Athanasia 2012, 30.

6. Evans cited in Raven 2000, 29.

7. Raven 2000, 29.

8. Morgan 1988, 40; Immerwahr, S. A. Painting in the Bronze Age, London, 1990.

9. Beckmann ‘Terebinth in Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age Crete,’ Athanasia 2012, 39.

10. Morgan 2005, 57–8; 147 and pl.3.2. Also, olive branches have been found in fragments at Pylos.

11. A fresco with vine leaves can be seen at House of Frescoes, Knossos; Ivy in the Cat and Bird fresco, Hagia Triada; ivy is also present in the upper zone of the Boxers and Antelope frescoes, House Beta 1, Akrotiri. A possible branch with pine needles appears in Room 5, Xeste 3, Akrotiri. Several dwarf palms are in the Nilotic Landscape frieze, West House, Akrotiri.

12. Baumann 1993, 176, figs 346–349; Raven 2000, 29.

13. Phillips, R. and Rix, M. The Quest for the Rose, London, 1993, 12.

14. Warren, P. ‘Flowers for the goddess? New fragments of wall paintings from Knossos’, in Morgan 2005, 142–143 (cf. pl. 16 painted by J. Clarke).

15. Morgan 1988, 39; Shaw 1993, 668–669.

16. Shaw 1993, 674.

17. Warren, P. 2005, 143 and 146.

18. Dimopoulu, N, ‘A gold discoid from Poros, Herakleion: the guard dog and the garden’, in Krzyszkowska, O. (ed.) Cretan Offerings, Athens, 2010, 89–100.

19. Morgan 2005, pl.10.2.

20. Morgan 1988, 18.

21. Castleden, R. Life in Bronze Age Crete, London, 1990, 46.

22. Shay, C. T. et al. ‘The modern flora and plant remains from Bronze Age deposits at Kommos,’ in Shaw, J. W. and Shaw, M. Kommos I, Princeton, 1995, 126 and table 4.12.

23. Castleden, R. Life in Bronze Age Crete, London, 1990, 52. Charcoal of lentisc (Pistacia) was found at Kommos (Shay, C. T. et al. ‘The modern flora and plant remains from Bronze Age deposits at Kommos,’ in Shaw, J. W. and Shaw, M. Kommos I, Princeton, 1995, 126)

24. Shaw 1993, 683–685. Shaw also suggests miniature iris and sweet violet were possible here.

25. Another suggestion is that these holes could have been used for grinding grain, but the rocky slope would be too difficult for this purpose.

26. As mentioned by Graham, J. W. The Palaces of Crete, Princeton, 1962, 87, 89, 91 (relating to Mallia); 123, 241. Also cf. Shaw 1993, 680.

27. Rackham, O. ‘The flora and vegetation of Thera and Crete before and after the great eruption,’ The Thera Foundation.org. 4.

28. Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 142.

29. Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 96.

30. Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 85 and 89.

31. Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 146.

32. Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 164.

33. Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 207–208.

34. Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 166.

35. Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 54–55.

36. Vlazaki, L. ‘Iris cretica and the Prepaltial workshop of Chamalevri,’ in Krzyszkowska, O. (ed.), Cretan Offerings, Athens, 2010, 359–366.

37. Castleden, Life in Bronze Age Crete, London, 1990, 52.

38. C.f. Shaw 1993, 663; Tzedakis and Martlew 2002, 266.

39. R. Arnott, from a lecture on medicine and herbs in the Aegean Age, held at the Gas Hall, Birmingham, Sept. 2002.