Greek Gardens and Groves of the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic Periods

Mycenaean culture collapsed around 1200 BC at about the same time that other contemporary cultures in the eastern Mediterranean were disrupted. There was a widespread movement of migrating people and internecine wars are also thought a possible contributor to the downfall of Mediterranean societies. The two great epics of Homer relate back to this turbulent time and have echoes from life in the Bronze Age. The epics were essentially oral tales that were finally written down in the 8th century BC, but inevitably over the centuries the epics had been embroidered and therefore contain later elements. However, they provide a link from the Bronze Age right through the so-called Greek Dark Ages and into Archaic Greece. Archaic Greece is generally accepted as extending from the 7th century BC to 480 BC, which is the date of the Greek victory over Persian invaders. After the Greek victory there was a flowering of the arts in what we term the Classical Greek period, which extended to 323 BC; this date marks the death of Alexander the Great and the start of the Hellenistic era.

Homeric gardens

In the second Homeric epic, dealing with the wanderings of Odysseus, there are descriptions of landscapes and even gardens. The first description of note relates to the surrounding area of the cave inhabited by the nymph Calypso:

right about the hollow cavern, extended a flourishing growth of vine that ripened with grape clusters. Next to it there were four fountains, and each of them ran shining water, each next to each, but turned to run in sundry directions; and round about there were meadows growing soft with parsley/celery and violets, and even a god who came into that place would have admired what he saw, the heart delighted within him.1

In many ways this idyllic scene reflects the naturalistic lily/iris filled areas of the Minoan world, and could be a memory passed down in an altered form. But, the details given in the longer descriptions of the gardens of Laertes and AlkinoÖs appear to be those familiar to the writers of the epic, rather than an earlier memorised one. They are nevertheless a very important source of information on early Greek gardens. One chapter in the Odyssey gives details about the palace and cultivated land (the garden) of Odysseus’s father Laertes. Tradition has it that these were on the Island of Ithaca. We hear that when Odysseus searched for his father he saw the familiar stone retaining wall of his father’s orchard, and found his father working around a plant. Odysseus spoke to him: ‘… everything is well cared for, and there is never a plant, neither fig tree nor yet grapevine nor olive nor pear tree nor leek bed uncared for in your garden.’2

In another section we hear about the garden of Alkinoös, the king of the mythical Phaiakians. These gardens became famous in antiquity as the ideal garden. A proverbial garden that was fertile, well watered and was abundantly fruitful – so much so that you could guarantee a never-ending supply of produce.

On the outside of the courtyard and next the doors is his orchard, a great one, four land measures, with a fence driven all around it, and there is the place where his fruit trees are grown tall and flourishing, pear trees and pomegranate trees and apple trees with their shining fruit, and the sweet fig trees and the flourishing olive. Never is the fruit spoiled on these, never does it give out, neither in winter time nor summer, but always the West Wind blowing on the fruits brings some to ripeness while he starts others. Pear matures on pear in that place, apple on apple, grape cluster on grape cluster, fig upon fig. There also he has a vineyard planted that gives abundant produce, some of it a warm area on level ground where the grapes are left to dry in the sun, but elsewhere they are gathering others and trampling out yet others, and in front of these are unripe grapes that have cast off their bloom while others are darkening. And there at the bottom strip of the field are growing orderly rows of greens, all kinds, and these are lush through the seasons; and there two springs distribute water, one through all the garden space, and one on the other side jets out by the courtyard door, and the lofty house, where townspeople come for their water. Such are the glorious gifts of the gods at the house of Alkinoös.3

These texts are useful in giving an indication of plants commonly planted in archaic Greek gardens, but it is clear that these texts do not describe a decorative garden as we would know it. Instead they seem to show a combined orchard and vegetable garden, and this practical way of gardening would have continued through the ages on properties in the countryside.

Greek names for a garden

The Greek word for a garden is Kepos (ϰῆπος) plural: kepoi. But, throughout the Archaic and Classical Greek periods this term usually referred to an enclosure of cultivated greens, more of a vegetable kitchen garden, or market garden, rather than a decorative garden. On occasion we hear of a kepouros (ϰῆπουρος) which was a garden keeper, this is the closest term we have for a Greek gardener. A garden plot or plant bed was called a prasiai (πρασιαὶ) a term that was already in use during the eighth century by Homer. The ancient Greek word used to specify an orchard was orchatos (ὄρχατος).

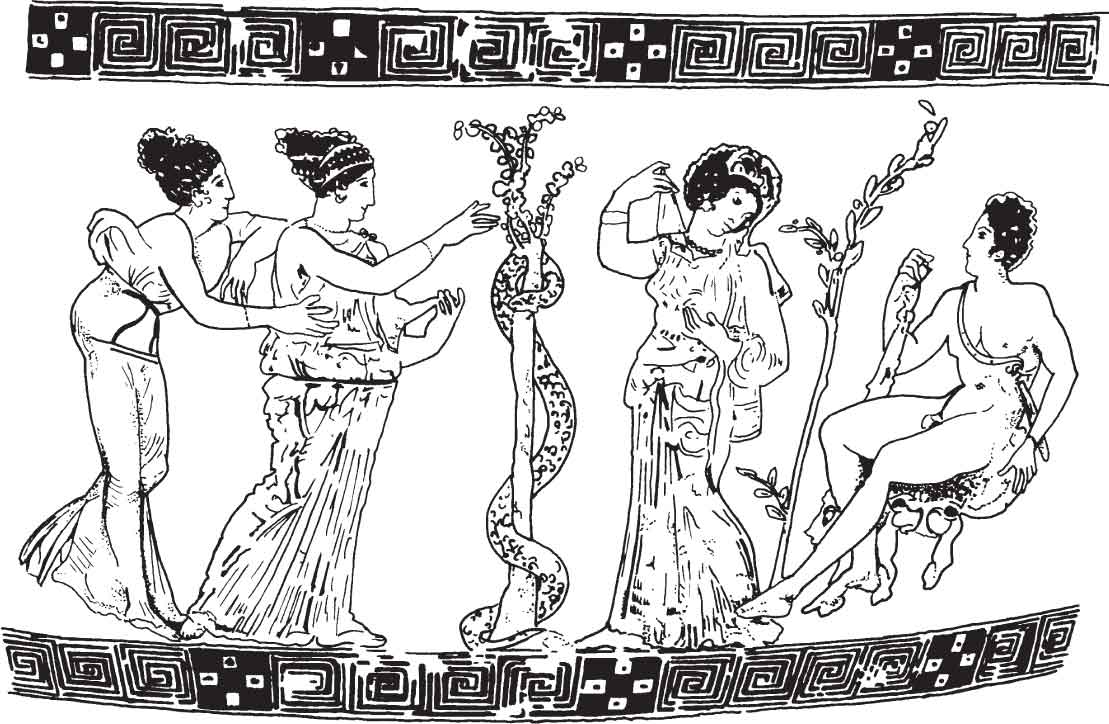

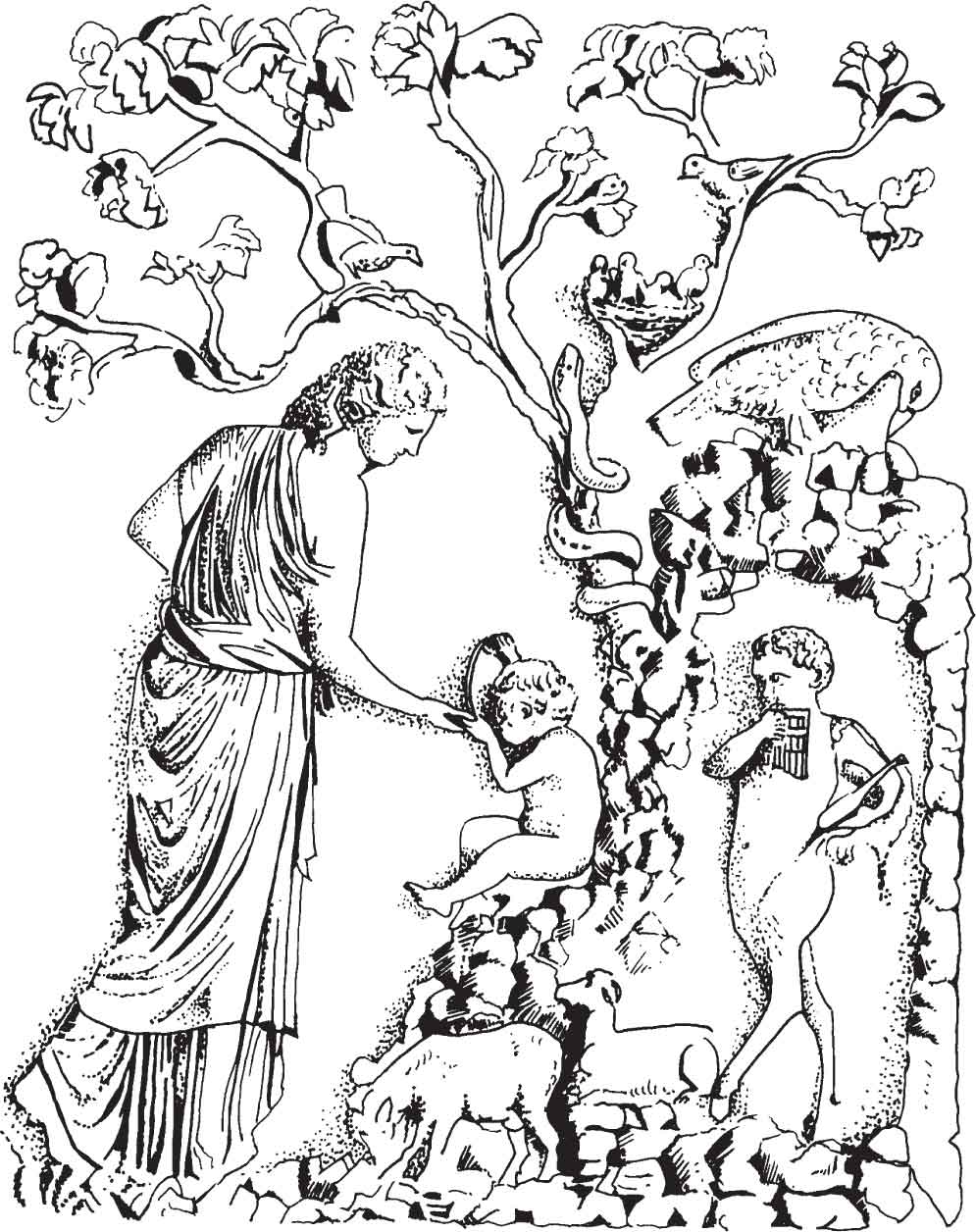

FIGURE 60. Hercules in the Gardens of the Hesperides, depicted on a Greek red-figure vase painting by the Meidias Painter. A snake guards the famous golden apples in this orchard garden, c.410 BC. British Museum, London.

The mythical Garden of the Hesperides

Several Greek myths centre around a garden, or garden plant, perhaps the most famous being the Garden of the Hesperides. These mythical gardens are associated with that great hero Herakles (known as Hercules by the Romans). Herakles was given 12 great Labours to accomplish, and the 11th of these was to collect the apples from this garden. The garden was said to have been far away in the west, on an island or close to the sea, and was tended by three nymphs called the Hesperides. A snake guarded the tree bearing the ‘golden apples’, Herakles had to kill this snake in order to get to the precious golden fruit. It is now generally believed that these fruit were quinces rather than apples, or alternatively they may have been citrons. This arduous task is immortalised in a Greek red figure vase painted by the Meidias painter. The vase is dated to c.410 BC, and is now in the British Museum.

Fertility cults

Every culture seems to have a basic need to pray to a higher being with the hope that they would come to their aid, whether asking for rain or for fertility in growing plants or agricultural crops. The Greeks sought to explain their own world and the lives of their gods and goddesses with a series of stories that became increasingly elaborate and these evolved into Myths. What is so interesting about the Greek myths is that so many of their gods interact with mortals. The Greeks had several deities that were concerned with aspects of fertility: Aphrodite, Athene, Dionysus, Demeter and Persephone, Pan, and at a later date Adonis and Priapus.

The goddess Aphrodite emerged from the sea (off western Cyprus) from out of an open scallop shell. She was the prime fertility goddess who was particularly concerned with aspects of love and sexuality, but also of beauty and grace (the Graces were often seen as her attendants). Roses and violets were particularly associated with Aphrodite, she was often called ‘violet crowned’. Aphrodite and Ares (the god of war) were lovers and produced a child called Cupid who had attributes of both: the power to incite love when he loosens his arrows from his bow. Aphrodite’s other dalliance, with Dionysus (the god of wine), produced a misshapen child named Priapus. His overlarge phallus was seen with distaste and after birth his mother abandoned him on the mountains. He was found and raised by shepherds; therefore he became a well known figure in rustic areas and was a powerful fertility god in his own right. He became noted as a guardian of orchards, vegetable gardens and bees. His cult originated in Lampsecus in Asia Minor but spread in the 3rd century BC.

Athene was a goddess of war, having emerged fully armed from the head of her father Zeus (the chief of the Olympian Gods). She was also a goddess of handicrafts and was known for her wisdom. One of her myths concerns a competition to see which two deities would take precedence in the city of Athens: Athene or Poseidon who was god of the sea. The two rivals challenged each other to prove which would be most useful to man [the challenge recalls the Mesopotamian contest between the palm and the tamarix]. Athene won because she produced the olive tree. Thereafter she was associated with the cultivation of olives, which became such a vital resource for Greece; the olive became her sacred plant. Athene had a long association with the city of Athens, and temples were built in her honour on the highest point of the Acropolis. As a mark of appreciation the Athenians built another sacred building the Erechtheion (next to Athene’s great temple, the Parthenon) where they added a small sacred garden around the olive tree first planted by Athene.

FIGURE 61. An olive tree sacred to the goddess Athena growing by the Erechtheion building on the Acropolis, Athens.

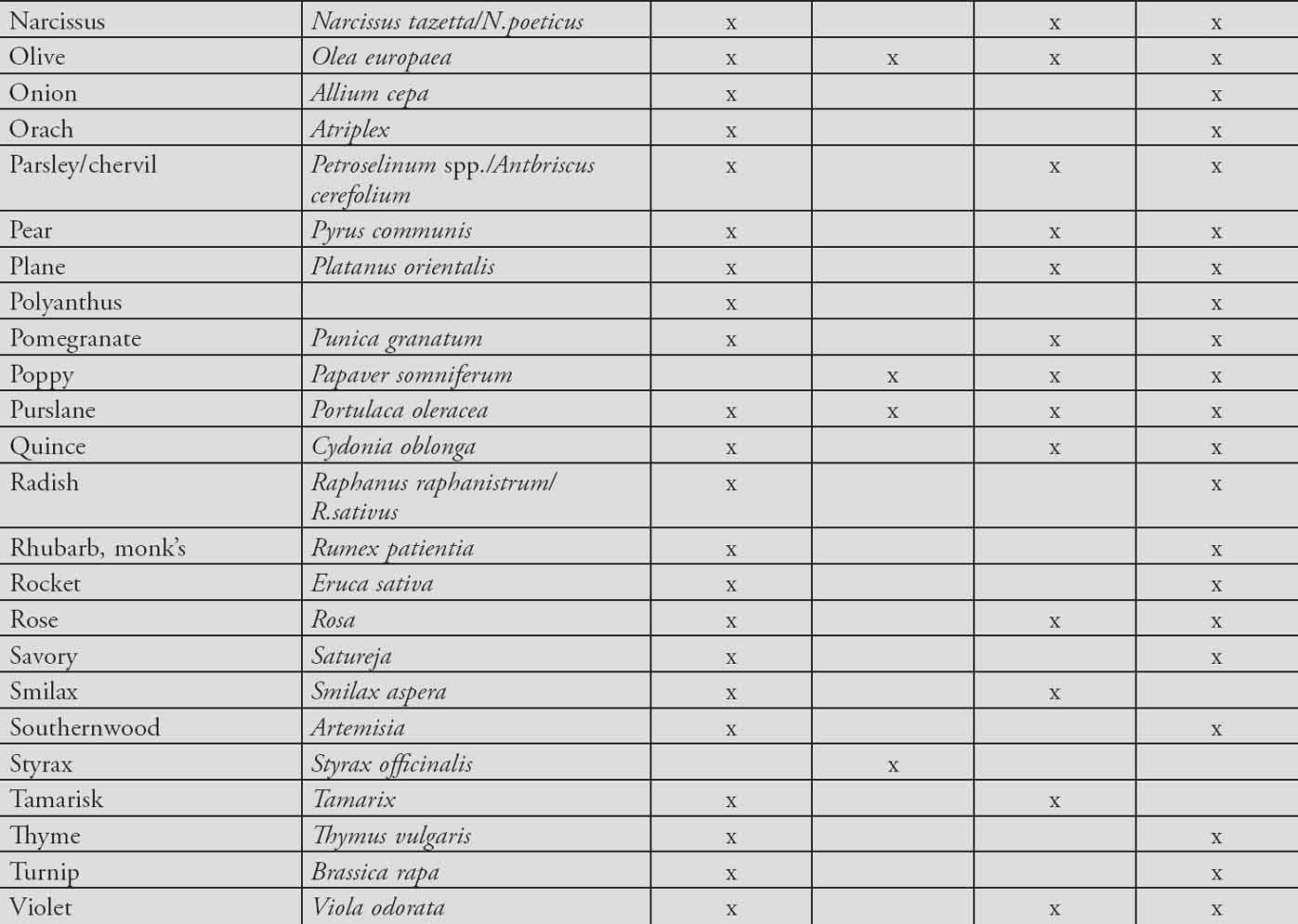

Dionysus was the god of wine, and is always associated with over indulgence in drinking and feasting. He was also the god of drama and theatre productions. Dionysus was the result of the dalliance between Zeus and a beautiful mortal girl called Semele. Naturally Zeus’s wife Hera was enraged when she learnt about their affair, and ensured her demise. Zeus hid the baby Dionysus in a cave on Mount Nysa where he could be looked after by three nymphs. While there Silenus acted as his tutor; Silenus himself was a demigod (sometimes thought to be the son of Pan) he was the wise drunken elder of the woodland satyrs, who undoubtedly initiated Dionysus into the joys of wine drinking. When Dionysus grew up he went to the east and to India, from where he returned in triumph, bringing back with him the cultivation of the vine. Because of this the vine and bunches of grapes are used as his symbol in art, and in some cases the vine appears to emanate from the god. Figs were also linked to the god mainly because they contained so many seeds, so they were seen as a symbol of fertility. Dionysus, or a member of his entourage, is often shown holding a thyrsus, a ceremonial staff. The thyrsus was made out of a long stem from the giant fennel (Ferula communis) topped with strands of ivy wound round and round to resemble a ball of ivy leaves; on top of which was a pinecone as a finial. The stem of the giant fennel was said to be softer than wood, if it hit you on the head during drunken revels. Also another reason for using fennel can be seen when you observe the emergence of this plant from the ground in spring: it is very phallic-like and this obvious connection to fertility will not have been missed. Ivy, like the vine, was also used as an emblem for Dionysus and his cult. In Classical representations of the god vine leaves and bunches of grapes were woven into a chaplet adorning his head, and ivy leaves and its flowers were used in crowns for members of his entourage which included Pan, Silenus, groups of satyrs (male woodland beings with pointed ears and tails) and maenads (female woodland nymphs). All of these are often seen on Greek vase paintings. One particular plant, the orchid became forever linked to the lusty satyrs mainly because of the shape of its roots: the ancient Greek word orchis implied a testicle! In ancient times like was used to cure like, so orchis was also in demand as an aphrodisiac. Some orchid flowers were even seen to bear a resemblance to the shape of a little satyr (especially Orchis italica; as its name implies it grows in Italy as well as in Greece).4

FIGURE 62. Detail showing Dionysus the god of wine, with a maenad carrying his thyrsus staff made from the stalk of the giant fennel and ivy leaves. Greek red-figure vase by the Kleophrades Painter, c.500–490 BC, Munich Museum.

Pan was the son of Hermes and a nymph. He was originally a god from Arcadia, a mountainous area in the Peloponnese, where he presided over shepherds and their flocks. His worship spread across Greece in the 5th century BC. He is particularly noted for the fertility of animals and of mountainous and country districts in general. Herbs grown in pasture come under his care. Pan is often associated with caves, where he would rest from the midday sun, and often his shrines were located in a cave setting. He was half man half goat, and because of his lusty nature he was prone to chasing nymphs and maenads; therefore he is often included in Dionysus’ throng.

From as far back as the Mycenaean era Demeter was the goddess associated with all aspects of growing corn, which was such a staple food in Greek diets. A recent study of the soils and plants around Classical temple sites of Greece has found that temples dedicated to Demeter (and Dionysus) were usually sited on land with good deep soil, and this is consistent with these deities’ association with fertility.5 One of her myths involves her daughter Persephone who one day was out gathering wild flowers when she was abducted by Hades (the god of the underworld) and was taken down to his realm. Hades wanted her to rule with him in the underworld, but she pined for sunlight. Her mother tried to seek her release, but all her entreaties failed. Her grief was so intense that the land became barren, the cereals would not grow and there was widespread famine. The gods were forced to act and a solution was found. Persephone could not return permanently to the land of the living because she had eaten some pomegranate fruit in her captivity, so she was forced to spend four (or six) months each year in the underworld. But for eight (or six) glorious months she was allowed to rejoin her mother in the light above ground. This myth attempted to explain why there were two very different seasons of the year; when Persephone was with her mother the land came to life once more, but when Persephone returned to her husband Hades winter approached and seeds became dormant in the ground. Because of this myth the pomegranate fruit was forever associated with Persephone. The cult of Adonis has a similar accounting for the seasons but will be mentioned later.

Greek myths concerning plants

There are 15 or more colourful Greek myths that weave a tale to give the origin of a plant/flower which we know as: olive, narcissus, hyacinth, crocus, smilax, bay, cypress, mint, heliotrope, fir tree, myrrh tree, tamarisk, helichrysum, achillea, adonis/anemone. The olive has already been mentioned. The myth associated with the narcissus flower is a sad one as the unfortunate youth Nárkissos (Narcissus in Latin), who had just turned sixteen, was so handsome that both girls and boys loved him, but he disdained them all. One day one of his thwarted lovers prayed that Nárkissos would share their same doomed fate of unrequited love. Nemesis, the goddess of fate, heard and granted this prayer ensuring that Nárkissos would fall hopelessly in love with the next person he saw. Nárkissos had been out hunting in the forest and came down to a pool to quench his thirst. He spied his own image reflected in the clear water and immediately fell in love with his own reflection. Every time he attempted to reach this image he failed and eventually he wasted away and died, to be replaced by the nodding yellow and white flowers that were thereafter given his name.

FIGURE 63. Narcissus hopelessly gazing at his own image, before turning into the narcissus flower. Seen in a Roman fresco from Pompeii.

The hyacinth flower was named after Huakinthos (Hyacinthus) another handsome youth that was loved by two rival gods: Zephyrus the god of the West Wind and Apollo. Huakinthos however, favoured Apollo and one day while they were throwing discus the spiteful Zephyrus decided to blow a gust of wind to deflect Apollo’s discus. Sadly the discus then hit Huakinthos on the head instantly killing him. Apollo could not revive him, so out of grief Apollo transformed Huakinthos’s blood into a dark blue flower, named after his beloved, so that it would ensure the youth’s immortality. However, in Greece the word for hyacinth was not specific to the botanical genus of that name, it encompassed several blue flowers including members of the scilla family, delphiniums and wild gladiolus. The latter bears the Greek sign of grief ‘Ai Ai’ on the lower lip of its flower which the ancients reckoned to be a mark of respect.

Another myth explains how the beautiful youth named Krokos (Crocus) became a flower. He was being pursued by the much besotted nymph Smilax. In desperation he pleaded with the gods to help him escape her persistent attentions. In answer the gods changed him into the crocus flower. Interestingly, Smilax who was a victim of her own hopeless passion was transformed into the prickly twining plant, forever clinging to others (Smilax aspera).

There is another sad story of how a beautiful shy girl called Daphne was transformed into a flowering bush. This myth was often reproduced in ancient art. The god Apollo fell in love with her, and was remorselessly chasing her everywhere. As in the myth of Krokos, Daphne despaired and prayed to the other gods to free her from his unwanted attentions, they heard her prayers and transformed her into the shrub we know as the bay tree. From then on the bay tree was associated with the god Apollo and it became his sacred plant.

Apollo was also fatally attracted to another boy named Kyparissos. The boy adored a tame stag that was sacred to the nymphs. One day Kyparissos was throwing his hunting spear but unfortunately it hit his pet stag that had been sleeping in the shade nearby. The boy was so heartbroken that he begged the gods to let him mourn for the stag forever. Apollo therefore transformed Kyparissos into a cypress tree (Cypressus), which became the classic symbol of eternal grief.

We can also consider the fate of the nymph Minthē (Menthe in Latin) who was the beautiful mistress of Hades (the god of the Underworld). When Hades’ wife Persephone heard of their affair she trampled Minthē underfoot. But Hades had the nymph transformed into the aromatic garden mint, so that when its leaves are bruised or trodden on the air is filled with fragrance and would be an eternal reminder of her.

FIGURE 64. Apollo pursued Daphne so much that she implored the gods to save her, they responded by turning her into the bay tree. The scene is immortalised in a Roman mosaic from Antioch.

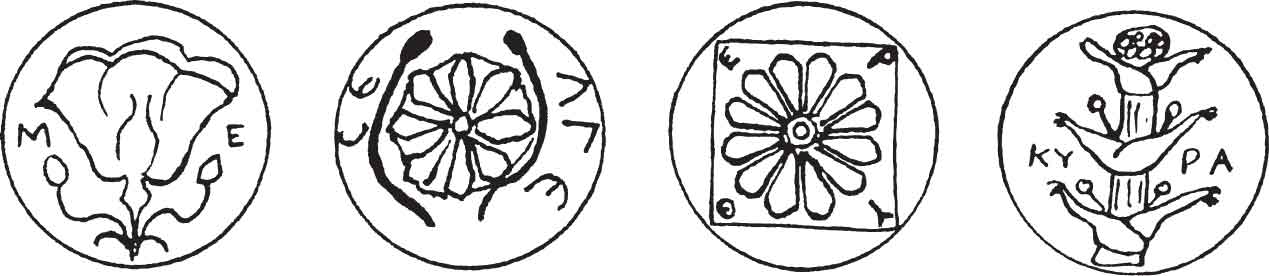

FIGURE 65. Flowers depicted on 5th–4th century BC Greek coinage. l to r: rose or cistus of Megiste, styrax from Selge; a daisy-like flower from Erythrae; Silphium from Cyrene (after R. Plant, London, 1979

Clytie loved the sun god Helios. But, when he fell in love with another she was so upset that she spread tales against her rival. When her rival was killed, and Helios did not return, Clytie pined. She sat on the ground and would only gaze up at the bright face of her god as he traversed the sky. Slowly she was transformed into a violet-like flower whose head follows the passage of the sun. She became the heliotrope.

A nymph named Pitys was wooed by both the Acadian god Pan and Boreas the stormy north wind. Tragically she preferred Pan because he was gentler, and so in revenge Boreas blew her over a cliff. On finding her body Pan changed her into the fir tree, which then became his sacred tree. Following on from this tale, in autumn her tears of resin fall from the tree. Pan features in another plant transformation concerning the nymph Syrinx; but in this case she did not want Pan’s attentions and was subsequently changed into the giant reed. Pan cut some stems and put them to his lips, to be as close to her as possible, and discovered the notes of what then became his syrinx/pan pipes. The giant reed (Arundo donax) is not actually a garden plant but Pan’s syrinx is such an important symbol/motif of the god in classical art that its mythical origins have a place here.

It is immediately noticeable that many of these myths have tragic endings for the mortals involved. None more so than Smyrna/Murrha (Myrrha in Latin) who was the daughter of Crinas. Apparently she refused to honour Aphrodite, and in revenge the goddess made her fall in love with her father. In despair Murrha decided to disguise herself to reach her love, but when her father discovered that she was pregnant, and that he was the father, he was furious. He tried to kill her, but she ran into the woods. She prayed to the gods to save her, they took pity and turned her into a tree (the myrrh tree) and from its heartwood Adonis was born. Her teardrops form the resinous juice myrrh, today obtained from the Arabian bush Balsamodendron myrrha. Murrha’s son Adonis was himself transformed into the adonis/anemone flower (the cult of Adonis will be discussed later). Another myth says that the sister of Adonis, Myriki, was changed into a tamarisk tree. The Greek word for tamarisk was myriki; the tree symbolised beauty and youth and became sacred to the goddess Aphrodite.

Other flowers are mentioned in myths: The helichrysum was named after the nymph Helichrsye who first picked its blooms. It translates as ‘the flower of gold’. Achillea was named after Achilles the greatest of all Greek warriors. On his way to Troy he inadvertently mortally wounded Telephus (the son of Herakles). The oracle said that the wounder, meaning the spear, would be the healer. So Achilles scraped some rust off his spear and from this sprang the plant achillea which healed the wound.6

FIGURE 66. Rose flower depicted on the reverse of a coin from Rhodes (© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford).

Another Greek flower mentioned in our sources is the dianthus. These were considered the flowers of Zeus ‘dios anthus’; anthus being the Greek word for flower. Roses and flowers in general were linked to the goddess Aphrodite. One myth implies that all roses were once white, but one day Aphrodite was running through the woods and a rose thorn scratched her. Some drops of her blood fell onto the rose flower turning it red. The rose concerned could be either Rosa gallica or R.phoenicia, both of which are ancient species.

Roses in ancient sources

Many ancient texts show that in Greece roses were picked for making garlands and also for making perfumed oils. Sappho, the 7th century BC poetess from the Island of Lesbos, informs us that the rose was her own favourite flower. It was universally counted as the most popular flower of ancient Greece, mostly on account of its wonderful scent.

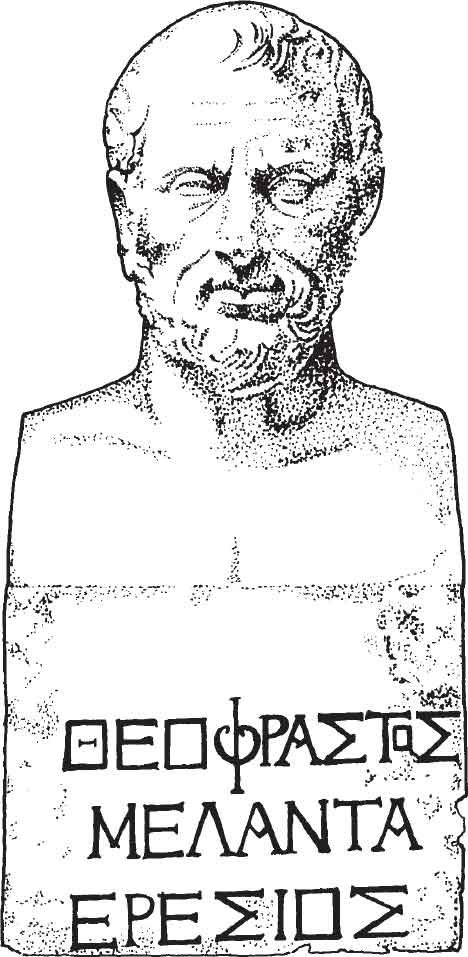

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus in the 5th century BC mentions roses, and interestingly a 60-petalled rose that grew in an area of northern Greece/Macedonia.7 A later writer, Theophrastus mentions a hundred-petalled rose ‘most of such roses grow near Philippi [Macedonia]; for the people of that place get them on Mount Pangaeus, where they are abundant, and plant them. However the inner petals are very small.’8 We can assume that these decorative strong smelling roses were planted in a form of garden. This is an important reference to the existence of gardens that are more than just a vegetable plot, but it refers to a practice in the 4th century BC (which will be dealt with later). The ‘hundred-petalled’ rose is not the centifolia rose we know of today for that was introduced to cultivation much later. The ‘hundred-petalled’ rose is now thought to have been a fully petalled form of Rosa gallica or alternatively Rosa damascena, or even a double form of Rosa alba.9

Flowers on Greek coinage

It was claimed that the rose grew prolifically on the Island of Rhodes or Rhodos (which was its Greek name meaning rose). Therefore the people of Rhodos decided to put this flower on the reverse of their coinage. The image does however bear some resemblance to a rock-rose (cistus) which also grows well on that island. In ancient times the term ‘rose’ could equally be applied to any flower that appeared similar to a true rose.

Several other Greek cities chose a plant or fruit as an emblem for their town,10 for example Naxos chose a bunch of grapes, and Eretria on the Greek island of Euboea had a vine with two bunches of grapes. The Island of Melos and the Greek city of Side in southern Turkey both picked a pomegranate fruit as their identifying symbol on coins. Selinunte chose a celery plant (Selinon was the Greek for celery) which grew abundantly in that region; so this was in recognition of the plant’s importance to their economy. Flowers of the beautifully scented storax (Styrax officinalis) were an emblem on the coinage of Selge, a Greek city in southern Turkey. Styrax shrubs grow wild in that region today. In ancient times the city was known for making perfumes from this flowering aromatic shrub (both styrax oil, and resin were used as incense). Styrax has a white flower that seems to resemble the equally highly scented Philadelphus, commonly known as mock orange.

Flower rosettes feature on some coinage: a simple eight-petalled flower was stamped on coins of Cyme, and a more distinct 12-petalled daisy-like flower was used on coinage of Erythrae in Ionia. Silphium was the enigmatic plant so important to the economy of the Greek city of Kyrene (Cyrene in Libya) and was therefore the identifying symbol on their coins. This plant appeared a bit like fennel and celery, but sadly in antiquity silphium was overpicked and became extinct. This was partly because it was a wild plant that resisted numerous attempts to cultivate it. The image on the city’s coins (plus carved column capitals at Beida) is the only visual reminders of this once important plant.

Wild flowers as opposed to garden flowers

Flowers as such are rarely mentioned in gardens of this period. However wild flowers were abundant in spring, and several Greek texts mention how the Greeks enjoyed picking wild flowers to make chaplets and garlands. The Greek word for a garland/chaplet was stephanos which originates from the verb stepho (to put round). Wild flowers can still be seen growing between trees in olive groves and they make a glorious sight. Olives were and still are one of the main crops in Greece. They are very nourishing and they provide oil for cooking and lamps, and as we have seen cultivation of olives goes back to the Minoan Age. Olives were grown in groves and along the edges of fruit orchards.11

Literary evidence shows a great fondness for wild flowers, but there is little evidence for cultivated flowers in decorative gardens in ancient Greece. There are many reasons for this, firstly a large part of Greece is mountainous, and is hot and dry in summer. Also, rather crucially, Greek people in towns and rural areas could only rely on a limited supply of water drawn by bucket from local springs, public wells and cisterns. Another important factor to consider is that in ancient Greece individual city-states often fought with each other and so for safety reasons many people chose to live behind strong walls. For this reason cities tended to be sited on a prominent hilltop or on an acropolis. The Acropolis in Athens is an example, this later became a sacred area, but the name is used elsewhere to denote a hilltop fortified settlement – an ‘acropolis site’. An example is Sillyon (a Greek city in Turkey) where the flat-topped hill, stands above the plain. There was once a large city on the top; on such a hill the ground is rocky and therefore houses could only have gravel or paved courts, as opposed to cultivated garden areas. These acropolis sites had no piped water, water had to be collected from a communal well or cistern. So with such a limited source this water was mainly reserved for human consumption.

Greek houses with courtyards

Plans of these towns show the density of housing on such an acropolis. Even at Olynthos in northern Greece the city was originally sited on a hill but when it expanded on the lower slopes of the hill in 432 BC, the highly planned and regulated rows of houses in the new section of the town were still small in size and close together. This was their preferred form of living. The city was conquered and not rebuilt so it has been possible to systematically excavate the site. Archaeologists have found that at Olynthos and elsewhere the Greek houses opened from the street into a courtyard which gave access to the rooms. The courtyards were not large, at Olynthos for example, the yards measured roughly only 51 m2.12 The surface of Greek courtyards was of gravel, or beaten earth. On occasion there may be a little altar located in the centre or to one side, there was no room for a garden.13

Archaeologists, however, found a couple of flower pots in one courtyard at Olynthos, indicating that at least a few potherbs may have grown there.14 On several sites archaeologists have discovered an enigmatic pit in the courtyard of Greek houses. There has been speculation whether this was used as a form of latrine. However as there is often a channel directing water into the pit, and the finding of numerous potsherds within them, it has been suggested that they may in fact have been a pit for planting a tree, or perhaps a vine.15 No botanical analysis has shown what species were involved.

Although ancient sources of the Classical period do not give any clues to indicate the existence of domestic town gardens in Greece, they do say that there were gardens outside towns. An example is quoted in Homer, Nausikaa says: ‘there is my father’s estate and his flowering orchard, as far from the city as the shout of a man will carry.’16 A tradition became established where people went out of the city by day, to tend their fields or market-style gardens and returned at night or when alerted to danger. Several references, gleaned from the Laws recorded by Aristotle,17 and from some of the comedy plays of Aristophanes (c.445–385 BC), indicate the existence of extra mural gardens. They mention that household refuse was regularly collected by civic dung collectors (from a large dolia kept just outside the front door!) and the contents were deposited just outside the town walls. This large heap could then be used as fertiliser by extramural gardeners.18 These ‘gardens’ were mainly used to grow produce though, because agriculture and horticulture in Ancient Greece was really aimed at self sufficiency. Although there were no private domestic gardens, there was another form of garden that was open to all citisens: the sacred garden.

Sacred groves and gardens mentioned in Greek literature

Sacred gardens could be found in or outside cities. There are numerous Greek references to groves surrounding temples or shrines and these were in fact, considered by the ancient Greeks to be a garden. Sometime the word alsos (ἄλσος) was used to denote a grove of trees. They could be small areas, such as that surrounding the Temple of Hephaestus in the centre of Athens, or if they were in more rural situations there would be more space and therefore be correspondingly larger. The earliest reference mentioning a sacred grove is found in Homer’s Odyssey ‘You will find a glorious grove of poplars sacred to Athene near the road, and a spring runs there.’19 In areas that were often ravaged by warfare, these places were all the more important, because by their very nature they were sacred, and so were regarded as sacrosanct. In fact there was a universal agreement that forbade the felling of trees in such sanctuaries – on penalty of death. So the tradition of having sacred groves or ‘gardens’ became well established. Apollonius of Rhodes mentions the Grove of Apollo at Kyrene with its myrtle trees.20 The area around Apollo’s temple today also has many fine bay trees, which were his sacred plant. The same city also had a Garden of Aphrodite, located near the spring, the myrtle which was her sacred plant must have extended into her garden area as well.

We also hear of the ‘gardens of Aphrodite’ at Athens, which surrounded her shrine. Such gardens needed water, and not surprisingly we tend to find that they are often located beside a stream. The Athenian ‘Gardens of Aphrodite’ are thought to have been close to the river Ilissos. To give an indication of what we might find within such sacred places Sappho provides a charming picture of the sacred grove around her local Shrine of Aphrodite (in the 7th century):

Come, goddess, to your holy shrine, where your delightful apple grove awaits, and altars smoke with frankincense. A cool brook sounds through apple boughs, and all’s with roses overhung: from shimmering leaves a trancelike sleep takes hold.21

This idyllic setting can be compared with that of a much later Hellenistic pastoral poet, Theocritus, who was writing in the 3rd century BC:

Along that footpath, shepherd, past the oaks, you’ll come across a statue, newly carved from fig, its bark still fresh… It’s in a sacred grove, close by a spring forever flowing from the rocks round bays and myrtles and sweet-smelling cypresses. A vine spreads out its tendrils there, and bears its fruit; in spring, the clear-voiced blackbird sings his lively tune and lilting nightingales return the song in honeyed notes. Go there, sit down …22

These extracts show a view of nature as a garden, but it is obviously not entirely a natural garden, because it contains a footpath, statue and a vine that is probably well tended. These sacred groves must have been enhanced as an offering to the deities who dwelt there, as well as being an attraction to visiting worshippers. You could say that the grand classical inspired gardens of places like Stourhead (in England) reflect this theme, of nature improved upon, and they help to recreate an ambience of the Greek sacred groves.

References indicate that offerings were sometimes hung on trees outside a sacred cave (usually ones that contained a spring) and as we have heard in some cases flowers were planted around the cave so that a little sacred garden would have developed nearby. This concept is recaptured in a Roman marble relief, and it gives an impression of how such a sacred grove might have looked in this period. In the relief a lady makes an offering beside a statue placed in front of a cave, while a young pan plays his pipes in the cave entrance.

FIGURE 67. Landscaped gardens such as at Stourhead were inspired by the Classical world; they effectively recreate the ambience of a Greek sacred garden with temple, statues and grove of trees.

FIGURE 68. Roman marble relief depicting a lady making a sacrifice in front of a cave sacred to Pan. This scene evokes the sacred gardens around caves in Greece, Lateran Museum, Rome.

Sacred gardens discovered by archaeology

In the centre of Athens a grove was created around the Temple of Hephaestus, this is situated to one side of the Agora (the large central meeting square of a Greek city). Archaeological excavations around this temple showed that on three sides two rows of planting pits had been dug into the bedrock. The square pits were about 88 cm wide, and would have allowed a sufficient depth of good soil for each tree. Each pit was found to have a broken earthenware flower pot in situ, which at last is firm evidence for horticulture. The pots had been deliberately broken; Theophrastus the Greek botanist (of the Hellenistic period) mentions the practise of layering plants in pots,23 these could then be used for transplanting trees. Sapling trees, still in their plant pots (but cracked so that root growth would not be held back) had been planted directly into their final positions around the temple. The orderly rows of plant pits were aligned with the columns of the temple. The size of the plant pits suggest that medium rather than large trees had been planted here giving a clue to its former appearance. Therefore when replanting the trees in the temple’s sacred grove some years ago they decided to have myrtle in the 1st row and pomegranate behind. This combination would not become too overgrown quickly and would not obscure the temple, and they would add to its beauty. The sacred garden was also provided with small flower beds, found near the precinct wall of the temple, but we can only guess which species were planted there because no evidence was found.

Planting pits have been discovered in association with other temples providing further evidence for sacred groves. At Corinth seven plant pits were discovered on the north side of the Temple of Asklepios.24 Twenty-three circular rock-cut pits were excavated by the Temple of Zeus at Nemea. The soil within these pits was analysed and has suggested that cypress trees once grew there.25 This is supported by a passage in Pausanias that actually mentions a grove of cypress trees around the temple.26 Evidence showed that the trees had been planted in the 4th century BC, but as earlier writers such as Pindar and Euripides mention sacred groves at Nemea it can be assumed that there had been an earlier sacred grove. To provide a link with the past cypress trees have been replanted around the temple site.

An interesting example for which some of the details are still preserved is the ‘Garden of Herakles’ on the Island of Thasos. This specific ‘garden’ included a special dining area for members of the cult. An inscription found nearby indicated that this particular ‘garden’ was apparently leased out, and would have supplied an income to maintain the cult. The terms of the lease stipulated that the trees (fig, nut and myrtles) should be tended, and that the lessee would be entitled to some of its produce.27 So, it appears that in some cases it was permissible to make a profit from cultivating part of a sacred garden; this may have been the case in other forms of Greek ‘gardens’. Vegetables would have formed part of the produce on leased plots and market gardens, but remains of vegetables and herbs are rare because they are so perishable. However, a rare waterlogged deposit found close to the Temple of Hera at Samos provided evidence for the use of these plants by devotees: beet; blite (a spinach-like plant); caper; celery; coriander; dill; lettuce (a wild form Lactuca serriola); oriental poppy and purslane.28 Pausanias (who had been travelling in Greece during the Roman period) mentions a venerable old willow growing in her sanctuary.29 His brief descriptions of sacred gardens he saw in or around sanctuaries gives us an overall impression that they were shaded by rows of cypress, laurel or plane trees.

FIGURE 69. Archaeological excavations around the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens revealed two rows of tree pits with plant pots in each pit, alerting them to the presence of a sacred garden here, (American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations).

FIGURE 70. Myrtles and pomegranates have been replanted in the pits to recreate the effect of an Athenian sacred grove (photo: D. Bruff).

Tomb gardens

Another form of Greek garden is one that accompanied some of the important tombs, kēpotaphia. In general tombs lined the approach to a city. Heroes were particularly honoured in this way with a shrine (heroon). Often the tomb monument and its garden were enclosed, and were treated as sacred areas. Funerary gardens usually comprised just trees and large bushes making a small grove around the tomb, for the simple reason that mature plants would not require constant attention and watering in a dry climate.

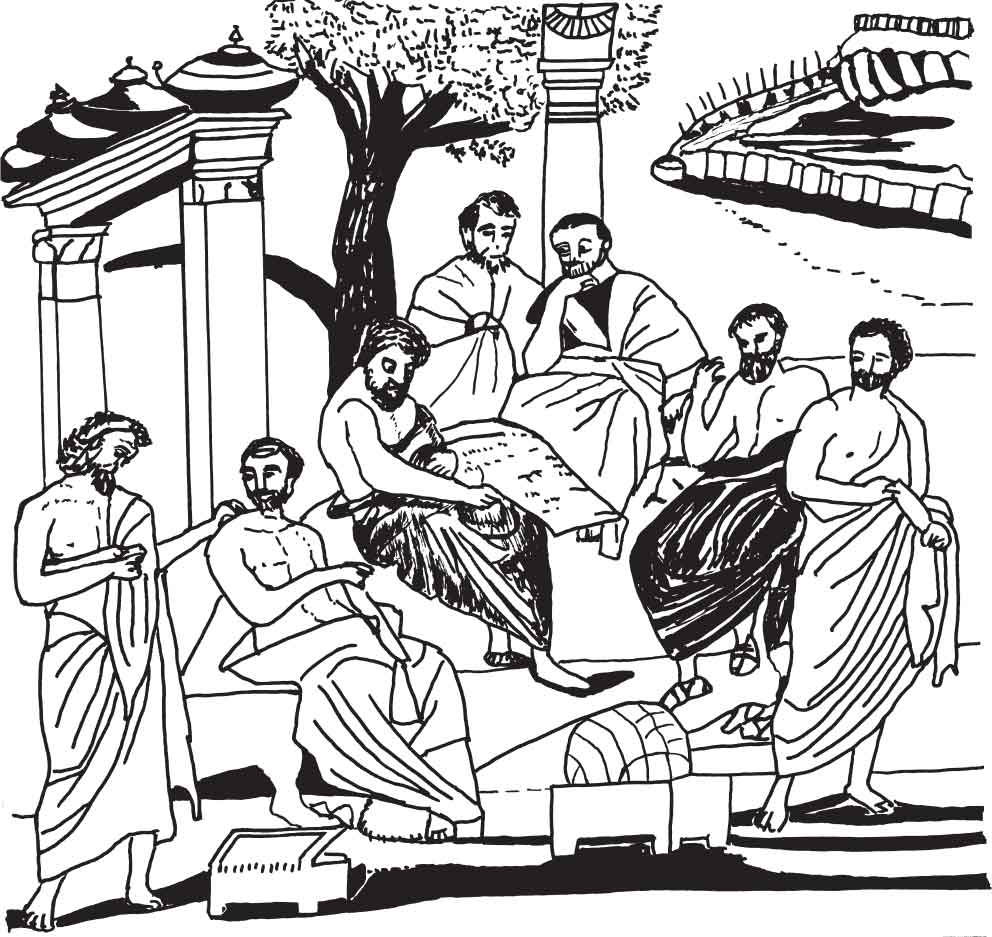

Civic groves in Greek literature

Plutarch tells us that the earliest known attempt to provide shade giving trees in the heart of a city was by the Athenian statesman Kimon in the 5th century BC. He planted a series of plane trees in the Agora of Athens, and brought water to a fountain house at the edge of the square.30 A mature plane tree has wide reaching branches and large leaves which creates excellent shade. Kimon also brought water to an area outside the city called the Akademy, so that a plantation could be established there. This measure led other later statesmen to make a similar gesture, for instance at Rhegion a Greek colony in southern Italy.

Three streams flow around Athens and along each of these there were groves of trees.31 The Kephissos River watered the Akademy, the Eridanos watered the area around the Lyceum and the Ilissos flowed through the Kynosarges area. All three areas were kept as a place for recreation and were much frequented by the populace, these groves could be equated as a form of public garden. They were used by athletes in training and by the ephebes, the young adolescent men who were obliged to train for war. It was also the duty of all citizens to make sure they remained fit in readiness for war and so they would come to have races and exercise – under the welcoming shade of the trees. Each area had springs where the men and youths could quench their thirst after their exertions. Because these groves became so popular, Greek-style gymnasia were set up in each area. Between races and bouts of training the men would discuss the world at large, and philosophers joined in their debates. This led to the establishment of philosophy schools in all of these three areas. Plato formed his School in the Akademy, Aristotle in the Lyceum, and the Cynics in the Kynosarges. A later period mosaic, from Pompeii, shows Plato in the Akademy and is representative of this Greek form of park-like garden. The philosophers are shown discussing under the shade of a tree, a mere token that represented the grove, and of all the trees the wide branching plane tree epitomised the Akademy. Above them is a sundial, and in the distance (top right) are the city walls of Athens which illustrates its setting outside the city.

Literary references give a wonderful impression of the groves in and around the Akademy. One text is taken from a comedy play by Aristophanes it relates to the physical training contests that would have taken place there, but also names some of the trees that you would have seen:

you’ll go down to Akademe’s Park and take a training run under the sacred olive trees, a wreath of white reeds on your head, with a nice decent companion of your own age; in autumn you’ll share the fragrance of leafy poplar and carefree convolvulus [smilax], and you’ll take delight in the spring when the plane tree whispers to the elm …32

The second text about the Akademy comes from the ancient traveller Pausanias (writing much later in about AD 160) he was mostly concerned with statuary and monuments that he saw, but his description infers that these may have been a feature of other park like groves.

Outside the city, too, in the parishes and on the roads, the Athenians have sanctuaries of the gods, and graves of heroes and of men… [he spied several of these on the way from Athens]. Before the entrance to the Akademy is an altar to love [Eros]… In the Akademy is an altar to Prometheus, and from it they run to the city carrying torches… There is an altar to the Muses, and another to Hermes, and one within to Athene, and they have built one to Herakles. There is also an olive tree, accounted to be the second that appeared. Not far from the Akademy is the monument of Plato…33

FIGURE 71. Roman mosaic illustrating the eminent philosopher Plato discussing in his Akademy grove, from Pompeii.

These are just partial descriptions of what the area was like, but they help to furnish a picture of these park-like gardens.

Garden themes on Greek vase paintings

Another valuable source of information on life in ancient Greece can be found in the scenes painted on their distinctive pottery. Sadly, surprisingly few Greek vase paintings depict flowers, and none of gardens, this was mainly because the Greeks tended to concentrate on the human form rather than on landscape or gardens.

Some however depict trees, an example can be found inside a mid-6th century BC black-figure painted cup where there is a wonderful overall design with a man holding large branches of two trees with two birds and a nest, plus a cicada on one of the branches. It makes a nice verdant scene. The cup comes from the Eastern Greek world, and is now in the Louvre.

At least three vases and fragments show girls/women picking fruit from an orchard. A red-figure painted vase of c.480 BC shows two women holding baskets to collect the fruit from a centrally placed fruit tree. This vase is one of a few signed by the artist himself: Pistoxenos Syriskos (the Little Syrian). It may be significant that the painter of this vase (like the previous example) may have been influenced by eastern horticultural ideas, because so few scenes depicting nature exist elsewhere. However, a similar red-figure vase with fruit pickers, painted by the Orchard Painter, can be seen in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Here the overlap in this painting tends to give the impression of a fruit tree growing in the large pot between the fruit pickers, but the tree is actually behind the pot which was placed there specifically to contain all the collected fruit.

Some vase paintings show diners on a couch under a vine, but on inspection the vine is really a decorative device to indicate the presence of the god of wine: Dionysus. Often the vine is not supported at all. On other occasions the vine is shown growing out of the god, as a reminder of his association with the plant and its produce – wine.

FIGURE 72. Red-figure vase with girls picking fruit, painted by Pistoxenos Syriskos.

Another Greek vase now in Florence (c.410 BC, painted by the Meidias painter) depicts the myth of Phaon playing the lyre in a bower. The bower is sketchily drawn, but it was seen as sufficient to signify an outdoor setting, presumably in a grove.

A 4th-century BC red-figure Sicilian vase portrays comic actors in a scene from a Greek play about Herakles and Auge. She was a priestess of the Temple of Athene at Tegea, and as he allegedly seduced her within the sacred precinct of the temple the stage scenery needed to include a representation of a sacred grove found within the temple confines. On this occasion a couple of tree branches placed on the temple’s altar, acted as a more practical substitute for full sized trees.

In Greece it was the custom to cut branches of sweet smelling myrtle and bring them into the house of the bride prior to the marriage ceremony. Literary references mention this practise, and it is beautifully portrayed on a red-figure painted vessel in Athens Museum. Young women arrange the twigs in elegant finely decorated pots.

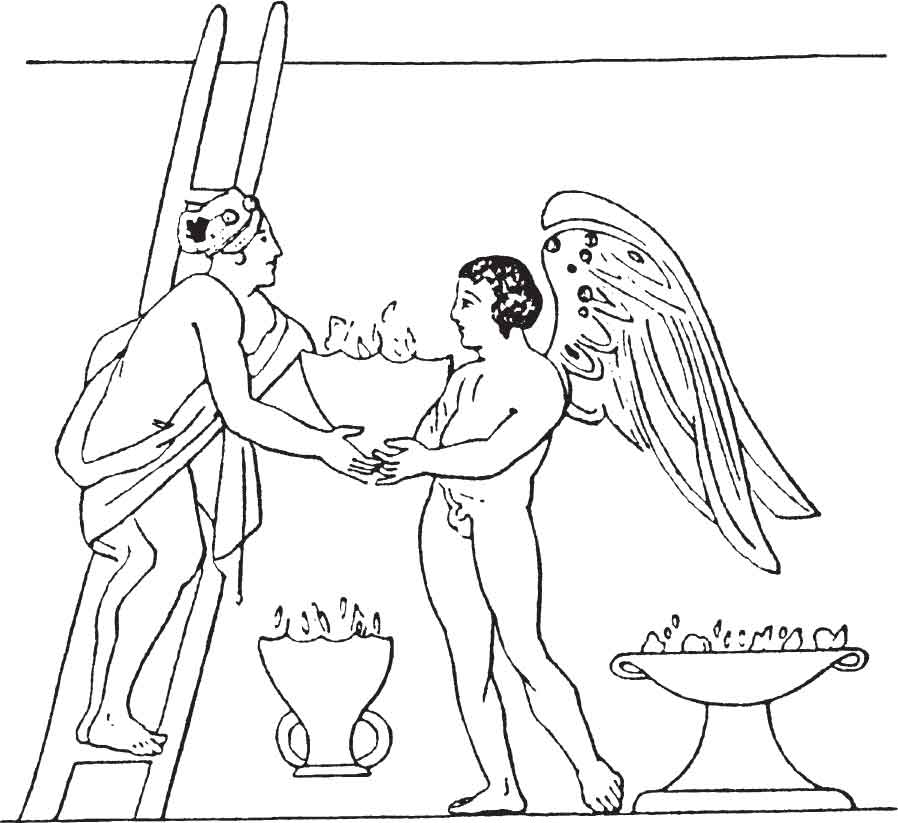

Adonis gardens

Broken pots/vases or broken amphorae were used as a planter for what is termed an Adonis Garden. A red-figure vase painting (now in the Karlsruhe Museum) shows three of these broken pots that constitute an important feature of the Greek and eastern cult of Adonis. The adherents of this cult and the planters of these pots were almost entirely married women and prostitutes, because it is primarily concerned with the cycle of vegetation and regeneration. Part of this cult involved sowing quick-growing seeds in old pots or broken amphorae, and after sprouting the pots were lifted onto the roofs of houses. The plants were not watered afterwards because they were destined to wilt and die in memory of the death of the god Adonis. In the vase painting Aphrodite is shown climbing half way up a ladder while her son Eros passes to her the ‘Adonis Gardens’ that were destined to be left on the roof.

One of the versions of this vegetation myth relates how Aphrodite had fallen in love with the beautiful youth Adonis. But he was mortally wounded by a wild boar while out hunting. Aphrodite was inconsolable and her grief stricken tears fell to the earth where they turned into the anemone flower. Both the adonis flower (Adonis annua) and red anemones (Anemone coronaria) are candidates for the flower concerned and both have a widespread distribution. Interestingly, in this tale (as with others) we find an occasion where Greek myths relate to each other, because while Aphrodite was rushing to the dying youth she scratched herself against a white rose bush, and her blood turned it red.

In the myth, Aphrodite was so distraught that she pleaded to the Olympian gods to have Adonis brought back to life. The story is touchingly recounted in Bion’s Lament for Adonis. Her plea was partly successful for Zeus decreed that Adonis would spend six months in the underworld, and he could return to her for the remaining six months. This decision forms one version of Winter and Spring. Another myth (mentioned above) features Ceres and Persephone, and in fact one version of the Adonis myth is also linked to Persephone who also loved the young man. She wanted him to stay with her in the Underworld, but the tug of love was solved by decreeing that Adonis would stay six months with her and six months with Aphrodite! So, in the Adonis rituals, the planted seeds reflect Adonis’s short return to life, and his untimely death each year. Although this cult originated in Byblos it spread to Asia Minor and Greece. It is mentioned in one of Aristophanes comedy plays: The Lysistrata, so it was already in Athens by the 5th century BC. The cult later spread throughout the Mediterranean. It is a rather strange form of gardening, but could have appeared as a garden in miniature. The seeds planted in these gardens were of either: lettuce, fennel, barley or wheat (quick growing ones). Today in Malta they put pots of cress beside the altar in their Churches at Christmas, perhaps to reiterate that old sentiment: that the seeds like Christ’s life would last but a short time.

FIGURE 73. Detail from a red-figure vase showing Eros offering a bowl of seedlings (an Adonis garden) to his mother Aphrodite who will place them on the house roof as part of the ritual in the cult of Adonis, Karlsruhe Museum.

Byblos, in Lebanon, was the ancient centre of the cult of Adonis. The cult ceremonies began when the water of the local river, the River Adonis, turned red. This was believed to be a sign that Adonis had died and his blood was being washed down river. This superstition came about through a phenomenon that still occurs after heavy equinox rainstorms wash the local red earth down river. In ancient times the people of Byblos then searched for his body. On finding a suitable log that could be substituted for his body, it was ceremoniously brought into the city and red flower petals would be strewn in his wake. There would be a day of lamentation following his death, and then the planting of the seeds.

It is possible that the Byblos cult of Aphrodite and Adonis could have arisen out of the Egyptian cult of Isis and Osiris translated into Greek myth. Isis and Osiris were connected to fertility and regeneration, and Byblos had many links with Egypt. A notable point is that Osiris’ coffin was washed ashore there. Also the Osiris beds, those shallow receptacles that mimicked his outline and were sown with seeds of barley, do bear a marked resemblance to the later Adonis gardens. These cross cultural links are intriguing.

The Greeks of the Archaic and Classical periods were restricted by the rugged terrain and their dry summer climate which meant that they could only rely on springs and well water, and in some cases whatever could be stored in a cistern. In these periods Greeks were also hampered by social factors: people mostly lived in densely populated cities, with little space for gardens. There were no palaces here, as in Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures, and no comparable aristocracy with large private houses and vast gardens. However, the Greeks made use of the abundant wild flowers in the countryside, by making chaplets to adorn their hair. They cultivated market gardens outside the city walls, and they had potager style gardens and orchards that appear to reflect Homeric descriptions of the Garden of Alcinoös. But, their lasting legacy was their rich collection of Greek myths, which were largely assimilated into later cultures. In gardening terms their greatest achievement was the creation of sacred gardens and groves, in cities and in rural areas. These statuary filled groves were admired by later visitors to their shores, they were plundered, but we find that later cultures would develop further this Greek concept, especially of a philosophical garden area to recreate their own version of the Akademy groves.

FIGURE 74. Adonis flowers (Adonis annua) in northern Cyprus (photo: B. Smith).

Macedonian and Hellenistic Greek gardens

The resurgence and meteoric rise of the Kingdom of Macedonia in northern Greece during second half of the 4th century BC under Philip II and his son Alexander, and their subsequent domination of Greece, had tremendous repercussions for the art of gardening in that region. With the introduction of monarchies came the desire for palaces and correspondingly large dwellings for members of the new ruling class. Some of these may have contained garden areas, but as scholars believe the palaces were rebuilt during the Hellenistic age details of the earlier palace/house and garden may be masked.34 It is possible that the gardens were inspired through contact with lands further east, such as southeast Thrace and Ionia that were at that time ruled by the Achaemenid Persians.

Gardens in Macedonia uncovered by archaeology

Aigai (Vergina, in northern Greece) was the traditional Macedonian capital city and a palace was built here by Philip II. The rooms of the palace were constructed around a large rectangular peristyle court (1600 m2), a smaller secondary court was added later. The two courts were open spaces and seem to have been kept as a garden, since there was no surface paving or other structures found within these areas. Stone rain water gutters survive in places along the edge of the colonnades, but no evidence was sought to find how the garden was planted as the site was excavated prior to the interests in garden archaeology. Previously Greek houses tended to have a form of portico (or stoa) on one side of their courtyard, but here the garden court was surrounded by four porticoes making a πєρίσтυλον (peristylon); Peri means around, stylon relates to the columns. The peristylon is thought to have been a Greek invention but one has been discovered in the Persian palace at Vouni in Cyprus (c.500–450 BC).35 The inspiration for this feature therefore, must be considered as coming from the melting pot of the Eastern Greeks and Persians. When there is more space it is a logical development to extend the stoa/portico to more than one side.

The Macedonian capital was transferred to Pella and another palace was built there by Philip II to replace a previous palace built by his predecessor Archelaos which had been destroyed by the Illyrians in 359 BC. The new palace and gardens were reconstructed on a lavish scale and included a series of colonnaded peristyles. One of the gardens measuring 35 × 30 m (1050 m2 in area) was found to have an altar in the centre, and the base of a semicircular seat on the western side. There was a pair of larger courtyards to the west of the residential section, and an even larger one beyond. The latter had a swimming pool on one side and has been identified as the palaestra/exercise area of the palace

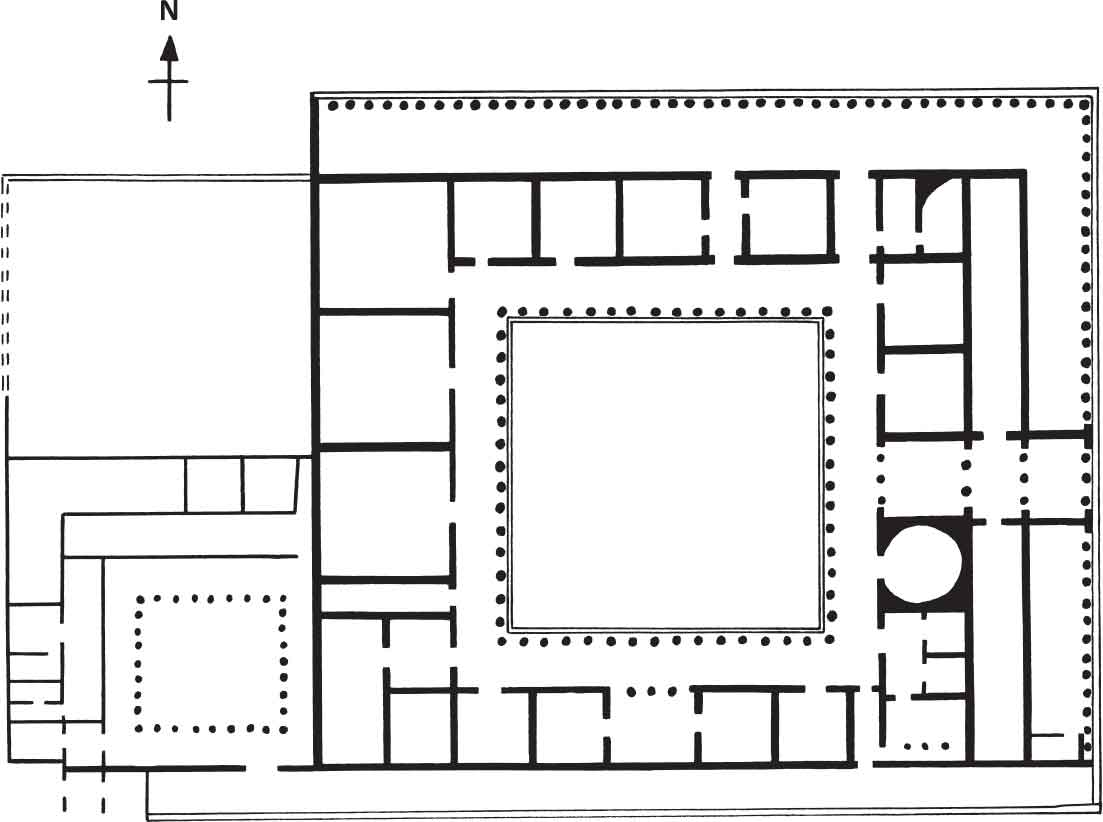

FIGURE 75. Plan of the Palace at Aigai, northern Greece, with two peristyle garden areas, 4th century BC.

There are also several large private residences at Pella that would have belonged to the faithful companions of the king; these were on a relatively smaller scale. One of the largest dwellings, the House of Dionysus, occupied a whole block of housing in the city; it had two rectangular peristyle courtyards, the smaller one was six columns wide (and can be compared with the peristyle garden at the palace at Aigai which was sixteen columns wide). The second colonnaded garden was 300 m2 in area and was found to have sections of a wide stone drainage channel still in situ around the edges. Today the gardens at Pella and Aigai are covered with grass, but evidence of former plantings schemes is lacking for no garden archaeology was undertaken.

Hellenistic gardens

Alexander the Great famously set out to conquer the Persians in 334 BC, and in the course of his conquest he led his armies through modern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan before returning through modern Pakistan. A campaign of twelve years throughout the region gave ample opportunity for his followers to absorb a range of ideas, including the eastern attitude to kingship and the level of luxury appropriate to royalty. The Macedonians and Greeks in Alexander’s army were amazed by the large well-stocked Persian gardens they saw. Alexander’s retinue included a botanist who recorded many new plant species, some were sent back to Greece; these will be mentioned later.

After Alexander’s death in 323 BC his empire broke up into a number of separate states ruled by his more powerful generals. After many years of war between them the survivors were: the Ptolemies who ruled Egypt, the Seleucid Empire that was centred on Syria, and the Kingdom of Macedonia itself which still dominated Greece. The period from the death of Alexander in 323–31 BC (being the end of the last of the successor kingdoms) is generally referred to as the Hellenistic Age. During this period the newly established royal families and their supporters had the wealth to support their ambitions for a luxurious lifestyle and one aspect of this was the possession of a Persian style paradeisos.

The garden areas are on the whole of a smaller scale than their Persian counterparts, but we can see that the Hellenistic concept of having a garden space in a palace was important. Instead of the palace being set within a large park-like garden, the Hellenistic palace often incorporated a rectangular or square garden area inside the palace itself. The Macedonians and Hellenes admired the way the Persians used porticoes for garden pavilions and this may have influenced the Hellenes to incorporate a version in their own gardens.

Peristyle garden courts were incorporated into palaces throughout the Hellenistic world, and we hear from Polybius that the Macedonian kings also had large well appointed game parks – also termed a paradeisos. As yet the only potential Hellenistic period game park that has been so identified is one at AÏ Khanoum (see below).

Archaeological evidence for Hellenistic Gardens

Few Hellenistic buildings survive because most were destroyed and/or underlie later structures, so there are difficulties in distinguishing which part belongs to the earlier Hellenistic phase. However, a peristyle garden has been identified on the acropolis at Pergamon in Turkey, which was the seat of the Attalid Hellenistic rulers. In one section of the palace, built in the 2nd century BC, a number of large reception rooms were arranged around a square porticoed area that appears to have been kept as a garden. Grass is growing in the garden today, but as this was a rocky acropolis the soil would not have been deep enough to support large trees there, and at the time of excavation no note was made of plant material.

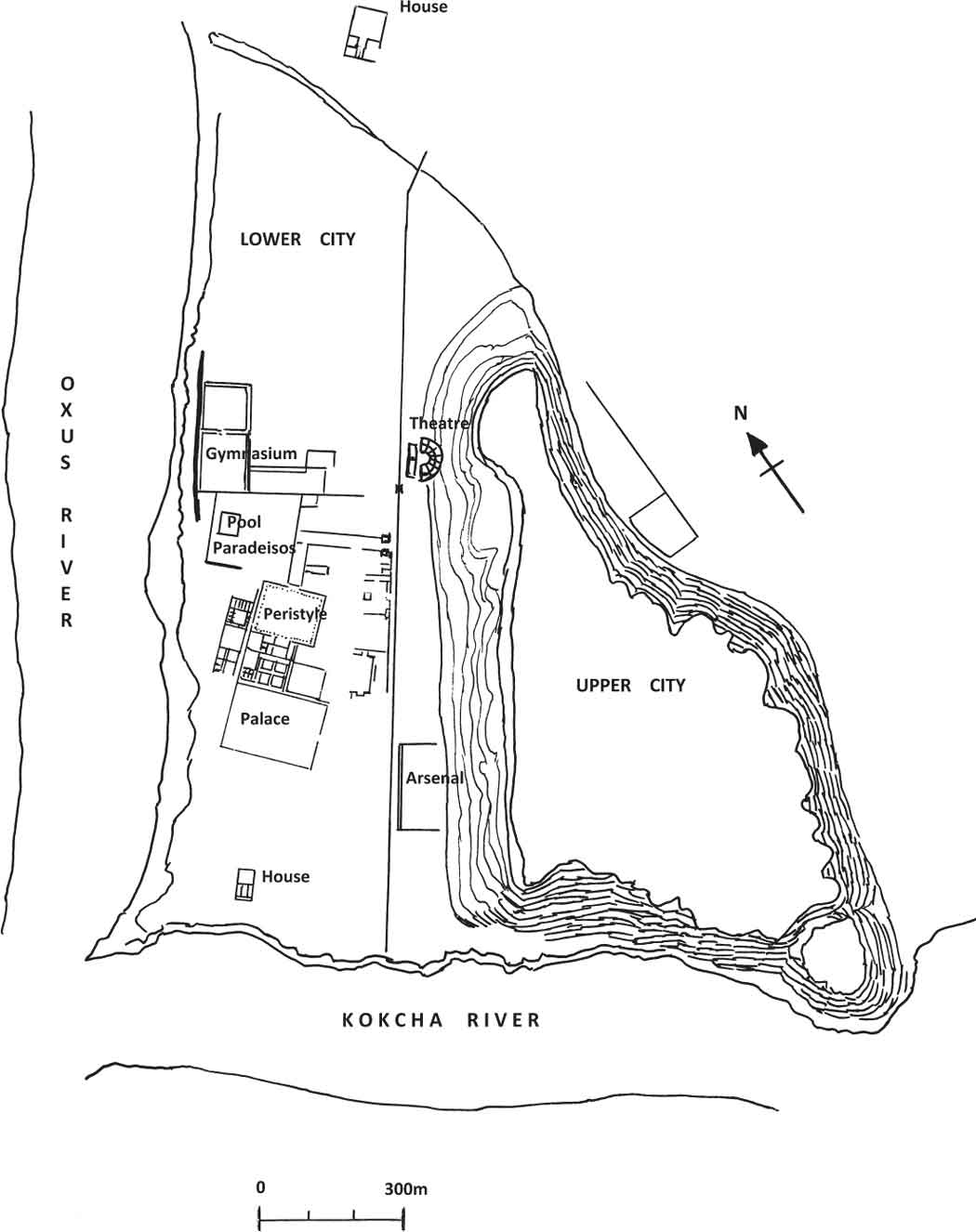

Further afield, at AÏ Khanoum, a Hellenistic city founded by the Seleucid kings (beside the River Oxus in northern Afghanistan), the rebuilt 2nd century palace also included garden areas set within a porticoed peristyle. The largest garden (that was perhaps used as a forecourt) was traversed before entering the palace and would have been awe inspiring for visitors. It can be measured by the number of columns in the four surrounding porticoes: 34 wide and 27 deep. A second peristyle of 16 × 16 columns may well have been a garden reserved for more private use. At AÏ Khanoum another portion of this site has been recognised as a large park or Persian style paradeisos of the palace. This region retained strong Persian/Bactrian influences therefore the melding of ideas here are interesting.36 The city fell to nomadic tribesmen c.145 BC and because of its remoteness the Hellenistic colony was not resettled or altered by successive cultures like the majority of other cities, therefore it gives a valuable insight into buildings and gardens of this period. Sadly no account was made of any garden features or paleobotany during excavation of the garden areas.

FIGURE 76. Plan of the Hellenistic palace at AÏ Khanoum, 2nd century BC. The palace was provided with peristyle courtyards, garden areas, and a paradeisos.

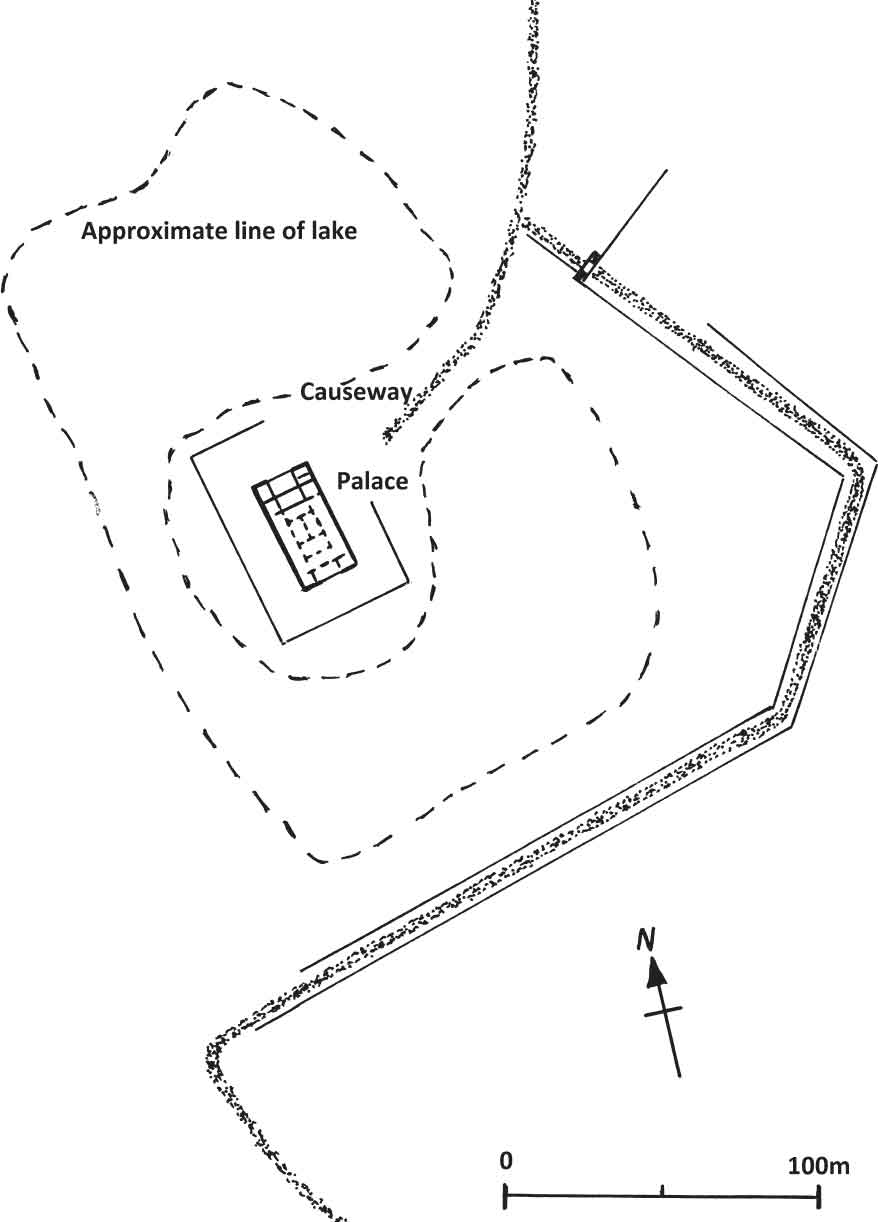

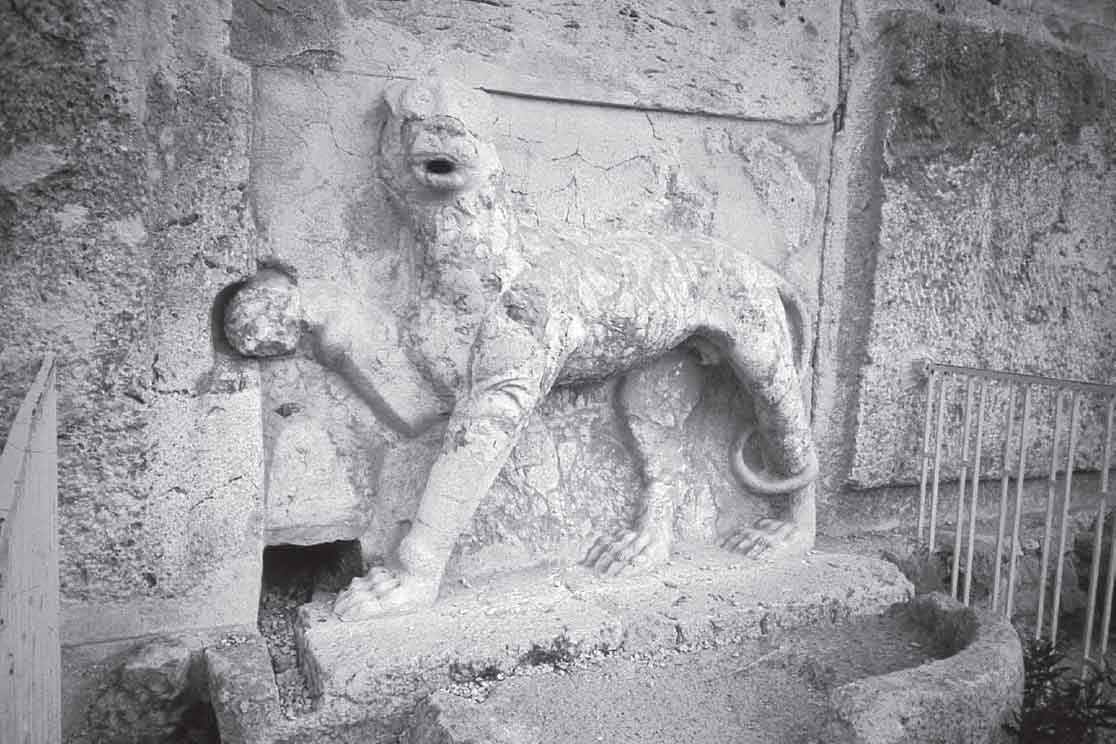

In Jordan there are rare remains of a Hellenistic palace at Araq el Amir (17 km west of Amman) which dates to the beginning of the 2nd century BC. The building is sometimes called the ‘Castle of the Slave’ because its owner Hyrcanus was descended from the local Tobaid priestly caste. His short lived palace was situated in its own little valley and is surrounded by a large enclosed park. We are fortunate that the Jewish chronicler Josepheus in his work on Jewish Antiquities gives a description. He mentions that there was a lake all around the palace, and that there were aulai (pavilions) placed in paradeisoi parks.37 There is still a deep depression around the palace that corresponds with the artificial lake mentioned by Josepheus, and there was a causeway to gain access to the palace. Unfortunately the aulai have not been located, but these may have been largely made of wood and so would leave little trace. One rather charming feature that would have enlivened the gardens close to the palace itself was a pair of fountains that had been placed on both of the long side walls of the palace. About a quarter of the way along each wall there was a carved leopard, standing with one paw raised and with his tail curled around its hind leg. Water poured from the animal’s mouth and gently flowed down into a shallow stone water trough. This enigmatic garden feature is a rare find in this period, but it shows that such items could have existed where there was a sufficient water supply nearby.

FIGURE 77. Palace of Hyrcanus at Araq el Amir, Jordan. According to Josepheus the palace was surrounded by a lake and was set in a paradeisos park with pavilions, 2nd century BC.

FIGURE 78. Leopard fountain at the Palace of Hyrcanus at Araq el Amir, Jordan, 2nd century BC.

When King Herod’s Winter Palace at Jericho in Judea (Palestine) was uncovered archaeologists carefully examined the garden areas (Herod reigned from 40–4 BC). Within the palace itself there were two peristyle courtyards that had been cultivated. In one of these, called the Corinthian peristyle, traces of plant bedding trenches came to light. The trenches had been neatly dug in rows, which is reminiscent of the orderly rows of Persian planting mentioned by Xenophon. However, no pollen was preserved to identify what species had been planted there. In the Ionic West Peristyle garden (B64, measuring 19.1 × 18.7 m, but with a planted area of 9.1 × 12.3 m) the straight rows of bedding trenches had been cut on a different alignment.38 The north–south orientated trenches were 1.5 m apart. Here the soil was examined and pieces of charcoal were found, these may indicate what was growing in the garden or might just represent local species in the vicinity brought to the site as firewood and the remains subsequently used as fertiliser. They were mostly of native species: Ficus sycomores, Olea europaea, Pistacia, Quercus, Tamarix, Ziziphus (and Juglans the only non-native). Carbonised seeds included those from: the Geranium family, Moraceae (Mulberry), Plantago indica, Trifolium, Lens and Triticum.39 A reconstruction of this garden was made showing a possible planting scheme where regular rows of balsam plants were laid out; these were highly prized plants specific to Judea (Opobalsamum gileadensis), and it is possible that they may have been grown in this garden at Jericho or nearby. We are reminded that in the Bible the prophet Jeremiah (8: 22) commented: ‘Is there no balm in Gilead’ because he knew that this was a major crop of that region.

Thirty-three flower pots have been found in the trenches of the Ionic garden at Herod’s Winter Palace. The pots were rounded but tapered at the base; three holes had been made in the lower part of the pot before firing to ease drainage. The upper rim of each pot was on average about 11 cm in diameter. A latex cast was taken of one of the pots, which was found to have a root cavity in its ancient soil infill, this revealed that a former plant root went right through the pot.40 Ancient sources (such as Pliny the Elder the great Roman natural historian) mention that these pots were used to make cuttings by air layering. To do this the pot is slipped over a young branch or shoot of a tree that you wanted to propagate, the pot was packed with soil, and then left to root for approximately two years. The pot is then cut off the parent tree and is ready to transport. The pots at Jericho had been planted straight into the ground, so must have already rooted. Some, evidently, had outgrown their pot because broken potsherds were also found. Tests revealed that these pots had been made locally.

Herod also constructed a large sunken garden at Jericho which lay on the opposite bank of the wadi. Next to this he placed a large rectangular swimming pool. His palace complex at Herodium also included a garden with another large pool, whereas two pools side by side were included in earlier Hasmonean palatial complexes at Jericho.41 The precedent for these pools is thought to be Egyptian rather than Persian.42 However, we need to consider the possibility that while previously living in Rome Herod may have been influenced by aristocratic garden designs he had seen, and these will be dealt with in the next chapter.

Apart from the royal palaces and dwellings of the elite, the average house of the Hellenistic Greeks was modest in size and they still preferred to have a practical paved court rather than a verdant garden. Examples of Hellenistic houses can be seen in the new residential area built at Priene (in Ionia), where the regularly planned houses were provided with plain courtyards as at Olynthus. However the average area of the open courts at Priene was originally 88.4 m43 which was relatively more spacious that those of Olynthos. Some houses at Priene were later subdivided and the yards correspondingly shrank in size, whereas others such as House 33 were enlarged and the owners were able to construct a full peristyle around their open courtyard, but this area was not kept as a garden. On the Greek Island of Delos, some of the houses did have open peristyle courts, but they covered it with gravel or mosaic. Even in the western Greek site at Glanum in southern France, a small paved court merely acted as a light well for rooms around it.

Hellenistic gardens and groves mentioned by ancient writers

Few texts mention gardens of this period. We know of a palace at Antiochia, a city founded by Seleucus I c.300 BC. The city (more commonly known as Antioch) was sited next to the River Orontes and the Seleucid palace lay on the nearby island on the river. Apparently the palace occupied about a quarter of the island, which would allow sufficient space for a garden. This city became a metropolis but as the site has been continuously occupied all vestiges of the Hellenistic city are deeply buried.

Strabo mentions that at the nearby settlement at Daphne there was:

a large shaded grove watered with springs, in the middle of which there is an inviolate enclosure and temple of Apollo and Artemis. It was the custom of the Antiochenes and their neighbours to hold a religious festival there.44

This was a large grove, but there was an important oracular shrine here and the area and its sacred groves were still treated with respect.

The luxurious life led by the Hellenistic rulers was often remarked upon by later writers, especially concerning the excesses in the city of Alexandria, named after the conqueror Alexander the Great. The city flourished under the Ptolemaic dynasty of kings. The city’s position on the edge of the Nile delta ensured that there was a plentiful supply of water for gardens. The Ptolemaic Palace had several gardens; the area of the palace and its grounds totalled almost a quarter of the entire city. We hear of the megiston peristylon that was used for receptions. The palaces were extensive and were surrounded by an alsos (park) with several pavilions. There was room for a form of zoo for we hear that agents sent rare animals to Ptolemy II, and apparently Ptolemy VIII bred birds in the palace grounds (he wrote a treatise on the topic).45 So the palace gardens incorporated some of the facets of a Persian paradeisos style of game park. There may have been botanical style gardens too. When Ptolemy II held a special feast in honour of Dionysus a large tent was erected in the grounds for entertaining, it was so large that 100 dining couches could fit into it, and statues were placed beside each wooden column supporting the pavilion.46 Branches of myrtle, bay and other boughs were placed on the outside of the pavilion, and all sorts of flowers were strewn on the floors so that it formed a ‘picture of an extraordinarily beautiful meadow.’ Because of the climate the gardens of Egypt were said to be able to grow plants and flowers in abundance throughout the year, so we can visualise a fine verdant garden here.

There were many groves of trees in Alexandria, so the city could be likened to a garden city. There was a museion area and library which had ‘a public walk, an exedra with seats’ next to a building where people could study.47 There was a sanctuary to Pan situated on an artificially made conical shaped hill. A spiral path led up to the summit from where there was an outstanding view of the whole city below. The Hellenes in Egypt were, of course, fortunate to have the benefit of centuries of Egyptian expertise in horticulture, and they may well have incorporated Egyptian features into their new gardens. Sadly none of these gardens are visible today because, due to changing ground levels, parts of the royal quarter are now below sea level, or are built over.

Records show that there were many paradeisoi in Ptolemaic Egypt, but on the whole this term was not confined to palm groves it was now used to describe utilitarian gardens including fruit orchards and for growing vegetables. The Fayum area in particular was developed into a series of farm and paradeisoi plots managed by Greeks, and interestingly some correspondence between officials and lessees has survived showing the management of these areas and the produce grown there.

Funerary gardens in Alexandria

Outside the city, to the west and east, there were large necropoli with numerous tomb monuments, Strabo said that there were numerous gardens in the suburb called Necropolis.48 Some of the enclosed funerary gardens of the kepotaphia were rented out for fruit and vegetable growing like the paradeisoi mentioned above.

In contrast the 3rd century BC tombs within the Moustapha Pasha cemetery at Alexandria were largely dug out of the bedrock and four of these were fashioned to appear like houses/buildings with rooms leading off open courtyards. Tombs 1 and 4 were given a peristyle around their square court; each had an altar in the middle but the surface of the court was left bare. Tomb Three though was highly unusual it was constructed to resemble a theatrical stage with backdrop, the owner’s funerary couch was placed in an alcove on centre stage; and the open area below (which would correspond to the theatre’s orchestra) was turned into a form of garden. Here walkways surrounded two rectilinear plant beds of unequal size; each bed had been edged with low limestone blocks. The beds had been excavated further to provide a deep layer for planting.49 Because these tombs were designed to resemble houses it seems possible that the garden plant beds reflect those seen in gardens of the living. These already pillaged tombs were uncovered during the 1950s prior to the emergence of garden archaeology and therefore an opportunity was missed to reveal evidence that could have informed us on the type of planting here, whether it was of vegetables, flowers, or a small grove of trees or shrubs.

A garden on a ship!

Hieron II of Syracuse (c.269–216 BC) had a stupendous ship constructed which became a classic sign of the excesses made during the Hellenistic period. Athenaeus gives us the details of this almost impossible feat of construction that was later presented as a gift to King Ptolemy and actually sailed to Alexandria.

On the level of the uppermost gangway there were a gymnasium and promenades built on a scale proportionate to the size of the ship; in these were garden-beds of every sort, luxuriant with plants of marvellous growth, and watered by lead tiles hidden from sight; then there were bowers of white ivy and grape-vines, the roots of which got their nourishment in casks filled with earth, and received the same irrigation as the garden-beds. These bowers shaded the promenades. Built next to these was a shrine of Aphrodite large enough to contain three couches… There was also a water tank at the bow, which was kept covered and had a capacity of 20,000 gallons… By its side was built a fish tank enclosed with lead and planks; this was filled with sea-water; and many fish were kept in it …50

This extract is the meagre surviving description of features that could have existed in Hellenistic gardens. However, the garden details given here may be a sign of over enthusiastic rhetoric in which Athenaeus was expressing ideas/features of his own time (c.AD 200) rather than earlier history.

The Hellenes continued to enjoy flowers woven into chaplets and garlands, which they wore when dining or celebrating in some way. Chaplets and wreaths were often composed of several different flowers and are mentioned by Athenaeus who often cited numerous earlier Greek writers. Here is an example that he found in Mollycoddles a play written by Cratinius:

I crown my head, to be sure, with all sorts of flowers- narcissus, roses, lilies, larkspur, gillflowers, bergamot-mint too, and the cups of spring anemones, tufted thyme, crocus, squills, and sprays of gold-flower, drop-wort and day-lily so well beloved, chervil too … tufts of narcissus, and with the perennial melilot I deck my head.51

We can speculate if all these flowers were included into one chaplet, or that these flowers were in different chaplets worn over the year. It remains an interesting list of plants that could be used for this purpose. Athenaeus reveals how some of the floral decorations were made and says that some wreaths were given special names, such as the one called Heliktoi (as mentioned by Chaeremon) it was apparently composed of ‘Chains of twisted wreaths trice-coiled all about with ivy and narcissus …’52

In some cases special chaplets to last an eternity were made of gold and placed in an aristocratic tomb to adorn the owner. One of the ones placed in the Tomb of Philip II of Macedon at Aigae comprised olive leaves and berries. Other golden chaplets have oak leaves and acorns; or myrtle flowers, leaves and berries. Such chaplets were also posthumously worn by influential women, such as the Hellenistic Carian princess from Harlicarnassus (Bodrum) who was given a gold myrtle chaplet to wear for eternity. These beautiful objects are finely made; they are light and delicate looking but have survived in an almost pristine condition. Such fine golden chaplets may also have been worn for special occasions in life.

Hellenistic Greek writers on plants

Callimachus, the poet and scholar from the Greek city of Cyrene, was given the enviable task of cataloguing all the books in the great Library of Alexandria (3rd century BC). During his time there he was undoubtedly influenced by the poetical works of earlier writers. Several of his hymns, epigrams, and fragments discovered on papyrus survive. One of the fragments, Iamb 4, is very interesting because it takes the form of a boastful contest between two trees: the olive and the laurel (bay). It is in a similar vein to the ancient Mesopotamian tale of rivalry between the palm and tamarisk trees, and we can wonder if Callimachus had heard of that earlier text. In this story the trees speak, and make much of their associations with deities: the bay was sacred to the god Apollo and the olive to the goddess Athene. The bay starts the contest by pointing out all the things in its favour: ‘But what house is there where I am not beside the doorpost? What seer or what sacrificer carries me not with him?’ the bay continued to extol its virtues and usefulness. But the olive tree’s reply was crushing; an extract from this speech reveals one of the reasons why, she asks: ‘What is the Laurel’s fruit? For what shall I use it? Eat it not nor drink it nor use it to anoint. The Olive’s fruit pleases in many ways: inwardly it is a mouthful …’53 not surprisingly she won the contest. Within this text is an interesting point showing how bay trees were regularly used in the home (probably as a pot herb) and were in a pot or in the courtyard itself ‘beside the doorpost’.

As mentioned previously the Athenian Xenophon, c.401 BC had the opportunity to see at first hand the different and luxurious way of life in the East. Xenophon’s account of his travels, the Anabasis, survives, written 30 years later, in which he spoke of the gardens of the Persian king. He also wrote the Oeconomics, a volume on the management of farms, but this says little on horticulture. Neither the writings, nor the experiences of those concerned in the expedition, seem to have affected the Greek form of gardening. But, during the conquests of Alexander the Great (from 334 BC onwards) a botanist took note of all the new plants they came across. Some of these were sent back to Greece and studied. This was a great period of discovery. The most influential man who made a study of botany and aspects of horticulture was the great philosopher Theophrastus.