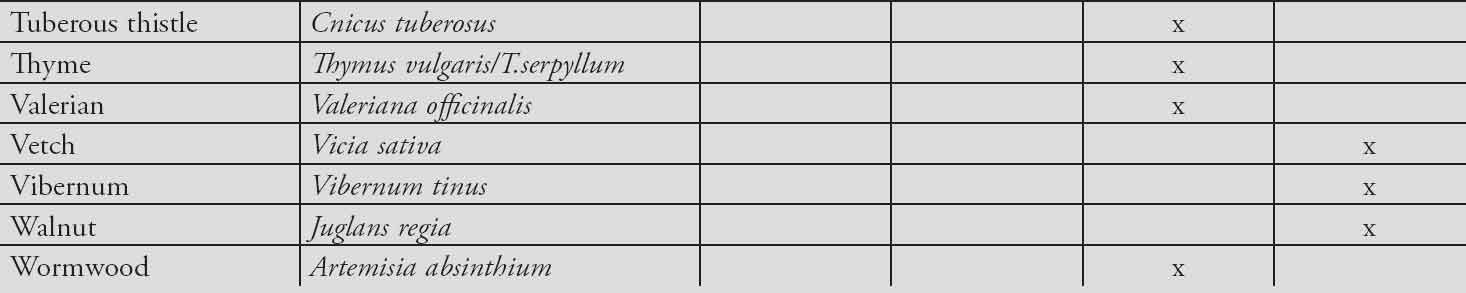

Etruscan Gardens

The Etruscans are believed to de descended from the earlier Villanovan culture in Italy which commenced c.900 BC, but the distinctive Etruscan civilisation is traditionally dated from the 7th to the 1st century BC. Their heartland was Etruria, a region named after these enigmatic people. This region is now in part of Tuscany and northern Lazio, but at one stage the Etruscans ruled a far greater area: as far north as Bologna and the Po Valley, and in the south as far as Cumae; their influence may have reached further. At one time the Etruscans even ruled Rome (c.616–510 BC). However, Rome eventually conquered Etruria and the much weakened Etruscans were amalgamated into the Roman way of life. Etruscan culture has had to be reconstructed from their rich remains discovered by archaeology because sadly their language (which was a non Indo-European one) has not been fully deciphered. Most Etruscan texts that have survived are fairly short, and can only hint at aspects of their mythology, religious practices or society. The Roman Emperor Claudius wrote a history of the Etruscan people, and this could have been a huge source of information on these enigmatic people, but sadly this has not survived. However, at times the Romans and Greeks (their rivals) have furnished small titbits of information on the Etruscan way of life in their own writings. So, it is largely through Classical literature and by the artefacts that the Etruscans left behind in their tombs that a picture of their culture can be assembled.

Etruscan deities with links to horticulture

Each Etruscan city may have had its own special deities, but there was one god that was important to them all: Voltumna. Every Spring there was a pan-Etruscan religious festival held at his great sanctuary at Fanum Voltumnae (near Orvieto) but only recently has the whereabouts of this special place been located.1 Here the Etruscans would consult and elect a new high priest and a supreme king over the chief twelve cities of Etruria;2 afterwards there would be great festivities and games. Voltumna was primarily a god associated with vegetation and the seasons. It appears that Voltumna later became the Roman god Vertumnus (his role in the Roman World is discussed in the next chapter).

Some gods had male and female counterparts like Cel and Cilens who were, respectively, the earth mother and father. Selvans was the god of boundaries and fields, and the countryside in general; the Romans adopted him into their own pantheon and gave him the name Silvanus (but the Roman Silvanus was notably a rustic god associated with woodlands). Over time many cultures adapt their ideas to outside influences and we also find that several Etruscan deities became equated with similar Greek gods; of these Fuflans took on aspects of the Greek Dionysus. Therefore Fuflans was associated with gaiety and vitality as well as wine and fertility. Turan was an Aphrodite-like goddess connected to love, fertility and health, and Atunis was an earth god who appears to have resembled the Greek Adonis. A more direct assimilation is noted in the Etruscan Phersipnai who is similar to the Greek goddess Persephone.

The town of Hortanum (Orte) may have been named after an Etruscan goddess called Horta, who was believed to be associated with Summer. Little is known about her, but she is thought to have been connected to agriculture and gardens, and her name may have led to the origin of the Latin word for a garden: hortus.

The Etruscans were known to be deeply religious and would readily seek help from their gods and priests on all matters. To the Etruscans the most important figure connected to agriculture was the mythical man-child Tages. The legend says that one day a man ploughing the soil by Tarquinia dug more deeply than was usual and from the earth emerged this little man who looked like a child but had the wisdom of a sage. Tages imparted his knowledge of agriculture to all the people who gathered around him, and disclosed the secrets of what became the Etrusca disciplina, the Etruscan art of divination.3 This great teacher is almost a god, and is commemorated on many Etruscan engraved mirrors. He appears as a small naked child, often below the groundline of the main scene, recalling the myth of his miraculous appearance; this is seen in the first mirror from the British Museum mentioned below.

Book three of the Etrusca disciplina (the libri rituales) was devoted to all forms of religious ritual. One of these interestingly gives advice to agri-horticulturalists to beware of certain plants in their orchard. If you would see any of the following ill-omened plants you would need to get rid of them immediately: a briar-rose, a fern, wild pear, black fig or red dogwood.4 These plants could soon take over and could indicate the loss of fertility in the soil, which would need remedial action. The books also indicates instances where the interpretation of omens could be sought in all facets of life; the flight path of birds could have significance for instance, and apparently there was even a work on prophesying from trees.5 Such comments may seem strange to us today, but nevertheless they do indicate that the Etruscans had some form of a garden, be it an orchard or a potager style garden.

Temple sanctuaries and groves

Several Etruscan cities had a temple sanctuary, such as the so-called Belvedere Temple at Orvieto which was sited towards the rear of a square enclosure. The Portonaccio sanctuary at Veii was triangular to suit the contours of the hilltop town, but there was a large space on the southern sector of the temple precinct. Each of these had areas that were possibly sufficient for sustaining shade trees. There was probably a sacred grove associated with the important cult centre of the Fanum Voltumnae (fanum means shrine). However at Marzabotto in northern Etruria, the Etruscan city with a regular planned layout was more spacious and the main sanctuary area with its temples was placed on two terraces of the acropolis above the city. The sacred sector of the town incorporated a nearby spring which was given its own shrine. Today this part of the site is covered with trees and gives the impression of a sacred grove.

Garlands

The Etruscan tomb paintings give a wonderful insight into Etruscan life, by depicting fashions and furnishings. Some of the frescoes show the owners enjoying their last feast and in some cases they hold a garland in their hands, or garlands are being made to give to the participants at the feast, as in the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing at Tarquinia (c.530 BC). In a number of frescoes painted garlands appear to be hung as if from a picture rail running along the upper part of the frescoed walls. The garlands are usually painted a uniform colour red, but in the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing the numerous garlands were differentiated. There are four different forms of garland repeated around the room: blue ones with red dots, red with dark red dots, yellow with a fringe of black lines, and purple with dark red dots. These may represent garlands comprising different flowering plants that unfortunately are unidentifiable. However, when garlands are carved on stone sarcophagi and funerary urns, they are often shown draped around the neck of the tomb owner reclining on his couch. These garlands show more details, often individual petals can be distinguished, sufficient to indicate that the majority of the garlands consisted of roses.

Tomb paintings and reliefs used as evidence for Etruscan flora

The Etruscans appear to have appreciated plants, for several frescoes depicting everyday scenes on the interior walls of their tombs use plant motifs as a border device running along the top of the wall. In the Tomb of the Triclinium at Tarquinia (c.470 BC) the painter chose a long sinuous stem of ivy, with periodic clusters of ivy flowers. In the tomb of the Bulls (c.540 BC) there was a row of pomegranate fruits. Many frescoes also frequently use trees to separate different figures or animals. An example is in the archaic period fresco in the Tomb of the Baron also at Tarquinia (c.510 BC). The trees were painted green but are stylised; we can make out that three different species were intended, but they are difficult to identify. A columnar tree could represent a cypress and another may have been intended as a laurel/bay which has alternately placed lanceolate leaves. In the frescoes of the Tomb of the Leopards (c.480–470 BC) the trees have similar shaped leaves but they are arranged in an opposite pattern along the branches which would indicate myrtles. Myrtles produce small black berries and these trees were also shown laden with black fruit (their identification is speculative because bay trees also bear black fruit, but are olive shaped).

A veritable grove of trees is depicted in the first chamber of the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, garlands and scarves drape from their branches. There are also numerous trees in the Tomb of the Bulls in the two superimposed scenes. The upper scene recreated an episode of Greek Homeric mythology. On the right Troilus the young Trojan prince approaches a sacred shrine and fountain outside Troy, but in the reeds behind the fountain lies the Greek warrior Achilles ready to ambush him. In this unusual rendition of the myth there is a dwarf fruiting date palm tree, and a lily-like plant behind one of the horse statues on the fountain and altar. There are also olive or myrtle-like sprigs nearby, perhaps to indicate a sacred grove. The seven trees in the lower section of this fresco have been carefully differentiated by their pattern of leaves and branching habit. The central one could be a broadleaf tree with a wide girth, but again they are schematic as are the other plants depicted in this particular fresco therefore the species intended cannot really be identified. One of the few flowers that are clearly depicted is the poppy, which has such a distinctive seed head. A bunch of three poppy stems are held by one of the ladies in the processional scene painted on the 6th century BC Boccanera panels (from Cerveteri, now in London). The lady behind her holds another bunch of flowers.

A flourishing grapevine features in the pediment and along the roof beam of the Tomb of the Triclinium, a figure on one side leans out as if to pluck one of the many bunches of grapes. The proximity of this scene to the diners below could be interpreted as reflecting a vine trained to grow next to their homes, in a garden area perhaps. Fruit are often included in frescoes and carved reliefs, where they are shown ready to eat, piled onto a dining table in banquet scenes. The most common species represented are bunches of grapes and pomegranates.

Plants depicted on Etruscan Mirrors

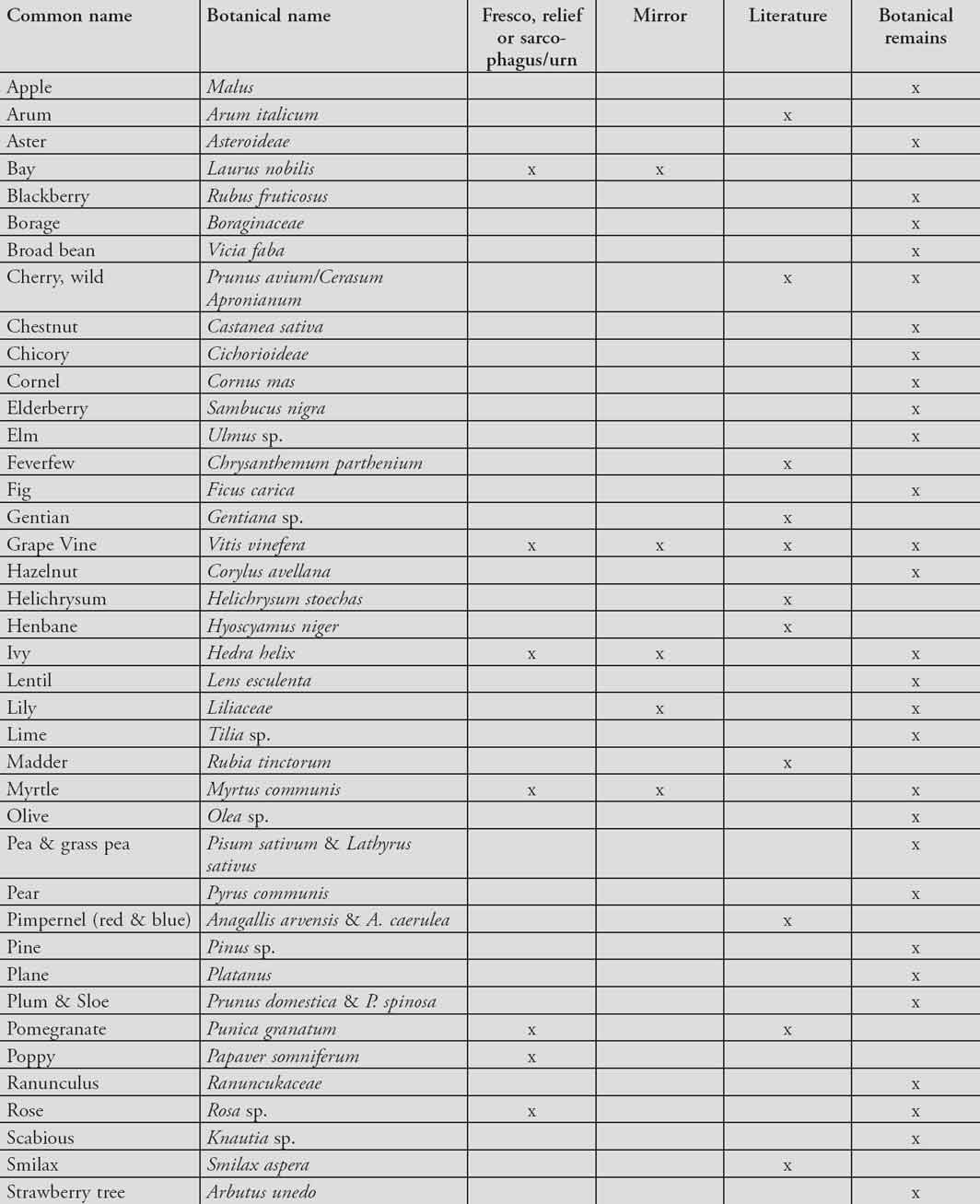

The mirrors are believed to have been a gift on a girl’s marriage; on the reverse side they often depict scenes from mythology and therefore floral elements are seldom shown. However there is often an outer frame of ivy around scenes engraved on the back of Etruscan bronze mirrors; alternatively a laurel wreath or trailing vine framed the picture. The main focus though is the figured scene in the centre, and on a 6th century mirror from Tarquinia (now in Berlin) the ivy seems to make a bower for an encounter/marriage between a young couple. Foliage rises behind the youth, and a small plant of ivy springs up between them. The young girl holds out a flower to her lover.

Another mirror from Tarquinia (now the British Museum) is framed by laurel, distinguished by its alternate leaves and berries. The main theme is of an augur or priest giving a blessing to another young couple. The groom carries a sprig from a bush, perhaps laurel or myrtle. Behind the augur there are three trees with a bird perched on top. The bird could relate to a garden setting but could also refer to one method of divination used by augurs based on the direction of a bird’s flight. Hopefully the auguries would be favourable for the young couple. A flourishing vine tree is featured below, with large bunches of grapes. The scene does give the impression of a garden or orchard.

FIGURE 81. Garden scenes engraved on Etruscan bronze mirrors. A. from Tarquinia, now in Berlin; B. from Tarquinia, now in the British Museum; C. now in Florence; D. now in Paris.

A mirror now in Florence, with a wide ivy border, portrays an interesting scene with a couple about to embrace. She holds a flower in the fingertips of her left hand. He holds a twig, again perhaps myrtle, but all around them are flowering plants, again indicating a verdant outdoor setting such as a garden.

One Etruscan mirror (now in Paris) features a man and a woman on pedestals, perhaps to signify they are deities. On either side is a vine tree laden with fruit. The man holds out his hand and in the palm of the proffered hand is a plant. The closely spaced leaves on the straight stalk could indicate a lily bulb with its growing stem. This is a highly scented plant and could have held some significance to the Etruscans, but sadly ancient sources are silent on this issue. A similar scene features on a mirror in the British Museum,6 here Turan and her winged son Eros offer each other gifts: a dove from Turan and a lily-like flower from Eros. Meanwhile a winged victory (Meanpe) flies above to crown Turan with a wreath of laurel or myrtle.

Medicinal plants

It is believed that the Etruscans used a form of Herbal. Occasional references by ancient writers gave the Etruscan name for certain plants, and glosses comparing these names with Greek and Latin were made. These were used in antiquity by an anonymous lexicographer/physician to add the Etruscan names of some plants to the Herbal manuscripts of Dioscorides. Of these, 11 names of plants are undoubtedly Etruscan and can be described as having a religious or medicinal use: arum, feverfew, gentian, helichrysum, henbane, madder, pimpernel (scarlet and blue), smilax, thyme, tuberous thistle and valerian.7 These plants can cure or ease symptoms of a variety of ailments, from toothache and eye problems, snake bite, for healing wounds, and even for ridding man and beast of internal parasites. The latter was a particularly debilitating problem and preventative measures were sought for in the Brontoscopic Calendar, a surviving text on Etruscan divination (thankfully copied and recopied). This important text highlighted the times of the year when heavy rains following thunderstorms could lead to an outbreak of liver fluke.8 Research into this infection has shown that a number of the plants mentioned above proved to be efficacious as a vermifuge (they contained toxins that could expell/destroy internal parasites). Several other plants identified on Etruscan sites would have been resorted to as a cure/preventative, amongst these are: chamomile, centaury, herb Robert, pomegranate rinds and roots, flax seed, ranunculus, wormwood and incense.9 Some of these plants are still used in various herbal remedies (except madder which was found to have carcinogenic properties);10 apparently the bark of Pomegranates is still used as a vermifuge in country districts in central Italy.11 It is therefore most likely that Etruscans, or the augurs and physicians at least, would have had an area of their garden plot devoted to medicinal plants.

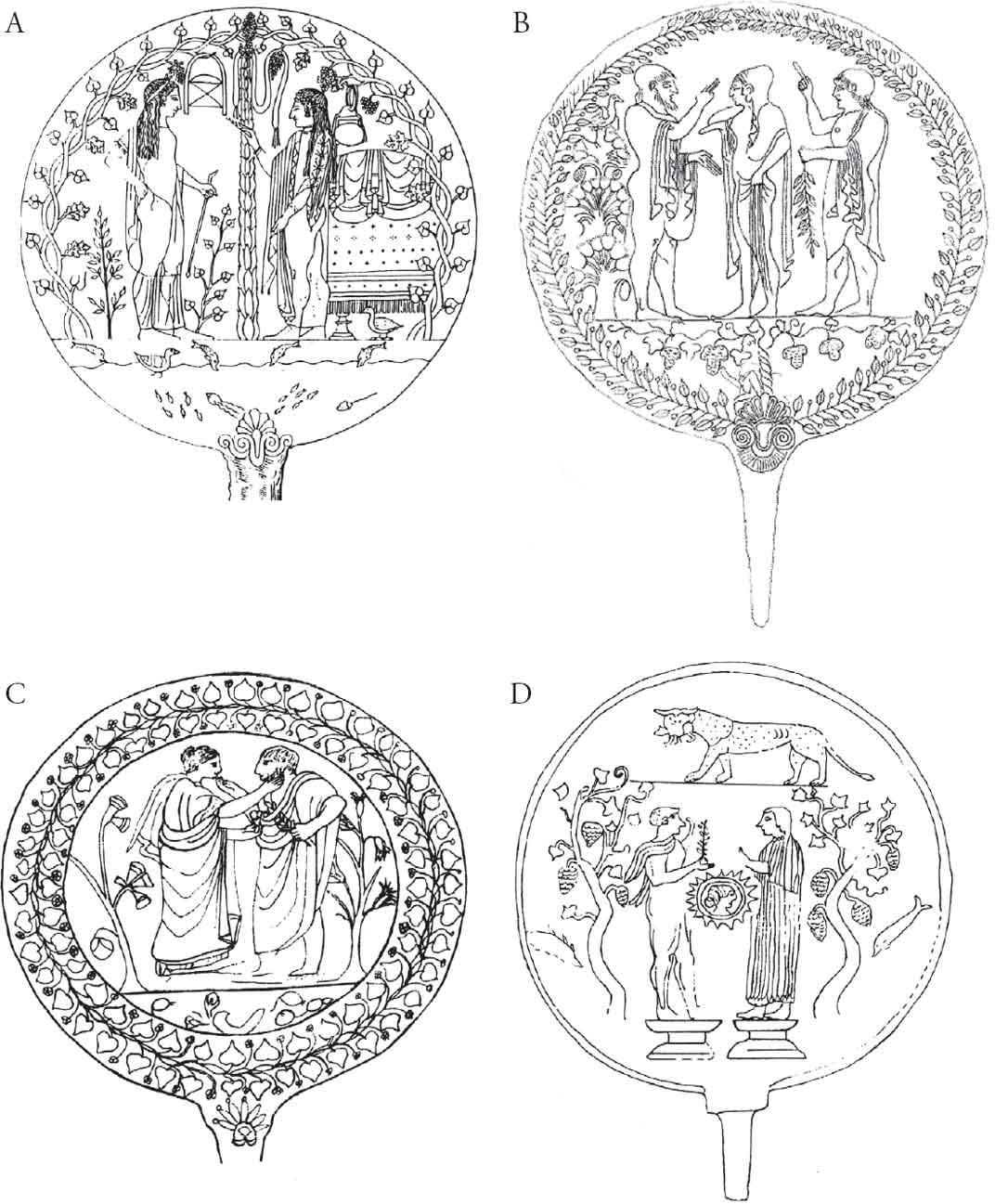

FIGURE 82. Detail of a stylised plant, possibly an arum. From an Etruscan mirror, Tarquinia, 4th century BC.

Archaeological evidence for garden plants

Most of the botanical investigations on Etruscan sites has concentrated on discovering what they had been eating, rather than what they had been planting. However, studies have shown that besides cereals their diet included chickpeas, lentils and peas that were discovered at Acquarossa; hazelnuts, walnuts, pine nuts, grapes, plum and other seed-bearing fruits, broad beans, lentils and peas at Verucchio;12 and olives, grapes, figs, pear, wild cherries and hazelnuts at Blera.13 These could well have been planted in a kitchen garden/orchard. The sweet cherry was unknown at this time so the Etruscans would have utilised their native species. The investigations of a 6th century BC farmhouse at Pian D’Alma discovered pollen, seeds and charcoal samples of a number of plant species,14 one of these was vetch (Vicia sativa). Six remains from spent fruit stones of cornel (Cornus mas) were identified; the cornel’s fruit is edible and until recently they were regularly harvested. Sadly though, in many cases only the genera of plant species can be identified, such as Rubus, Malus, Rosaceae, Liliaceae, Asteroideae, Caryophllaceae, Boraginaceae and Labiatae. Many of the species found at this site have been interpreted as being woodland plants, and some are certainly from weeds (such as Urticaceae – nettles) although they can be edible. You might also find them on cultivated land, perhaps even a garden plot that needs weeding from time to time.

An Etruscan agriculturalist

Latin sources reveal the existence of an agriculturalist named Saserna in the 2nd century BC, whose work was continued by his son. His name is Etruscan and apparently he lived in the north of Italy, but only tantalising relics of his writings on agriculture have survived in the works of others. As garden culture is akin to some of the practises performed in agriculture his books on the subject could have revealed interesting ideas. Apparently Saserna was given praise in some quarters, Columella said he was ‘no mean authority on husbandry.’15 In a surprising instance of an earlier global warming Saserna was said to have believed that the weather was getting warmer and this would enable people to produce larger crops of olives and grapes16. Pliny the Elder mentions that Saserna and his son disapproved of growing vines supported on trees.17 He was mostly praised for his advice on vines, and his methods of ensuring the survival of cuttings was heeded by later agriculturalists.18 Besides making wine at home for friends and family the Etruscans were known to have cultivated extensive vineyards and were skilled at making their wines. They exported their surplus, and we hear that Tuscan wine was appreciated in Greece.19 In fact Etruscan wine amphorae have even been discovered on sites in southern France, Spain, Sicily and Greece. A number of ancient shipwrecks have been discovered off the French coast, and by Cap d’Antibes divers found a cargo of around 180 Etruscan amphorae.20 This shipwreck was dated to the mid-6th century BC. The wine of Etruria (or Tuscany) is still well thought of.

Saserna also recommended using plants that could enrich the soil such as lupine, beans, vetch, bitter vetch, lentils, the small chickpea and peas.21 However, he was at times mocked for resorting to superstitious methods. For instance Varro recalls the method used by Saserna to disinfect things, he recommended people to ‘Soak a wild cucumber in water, and wherever you sprinkle the water the bugs will not come.’22

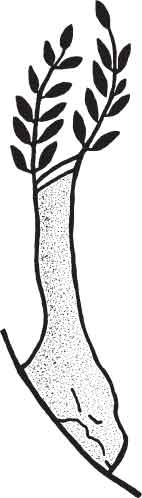

Evidence illustrating the skill of Etruscan aboriculturalists is found on an Etruscan mirror depicting a scene from the Myth of Bellerophon. On either side of the hero there appears a heavily pruned tree. The trunks of these trees have been cut off and two scions have been grafted onto the trunk of the parent tree. This could be interpreted as crown grafting which is done to rejuvenate an old fruit tree.

Etruscan gardens

No direct evidence for a garden space has been discovered archaeologically, as yet, although the large early form of peristyle courtyard within the 7th–6th century BC Palace of Murlo may have had at least some trees for shade. The archaic houses at Acquarossa (c.600 BC) were grouped around a central communal area but two of the houses also had a rear doorway which the excavators have suggested led to a back court or garden.23 Around 550 BC the houses at Acquarossa were enlarged and were given larger courtyards, but evidence is lacking to determine if part of this could have been used as a garden.

FIGURE 83. detail from an Etruscan mirror depicting crown grafting on a tree, now in Florence.

At Marzabotto the regularly planned houses within the Etruscan city had a prototype atrium Tuscanum (this feature is discussed in the next chapter) but no garden. The difficulties in searching elsewhere for evidence of gardens in this period is complicated by the fact that the Etruscans generally lived in communities sited on defensible hilltop places, and many of these sites are still occupied as towns today, which hampers any archaeological excavation there. Hill top towns tend to be densely populated and although there may have been some garden areas inside the town walls most gardening/horticulture would have been outside the walls. Therefore the enigmatic scenes depicted on the Etruscan bronze mirrors and tomb walls can only give some hint of the nature of horticulture practised in this period. The Romans so effectively took over the Etruscan people that after a while their language and their distinctive culture died out. But over the years of living in close proximity to Etruria there were inevitably cultural exchanges, and the Romans benefited from the rich legacy left by the Etruscans.

Notes

1. Stopponi, S. ‘Orvieto, Campo Della Fiera – Fanum Voltumnae’, in Macintosh Turfa 2013, 632–654.

2. The venue is mentioned by Livy 4, 23,5; 4, 25,7. trans. A de Sélincourt, London, 1971.

3. Cicero, De Div, 2, 23. trans. W. A. Falconer, London, 1923.

4. Thulin, C. O. Die Et. Disciplin: 3, 1909, 86, cited by Heurgon, J. Daily Life of the Etruscans, London, 1964, 112.

5. de Grummond, N. T. ‘Haruspicy and augury,’in MacIntosh Turfa 2013, 544.

6. B.M. Number GR 1840. 2–12.8. Swaddling, J. Etruscan Mirrors, London, 2001, 52–53, fig. 32b.

7. Johnson, K. P. ‘An Etruscan herbal?’, Etruscan News 5, 2006, 1 & 8.

8. Harrison, A. P. and Turfa, J. F. ‘Were natural forms of treatment from Fasciola hepatica available to the Etruscans?’, International Journal of Medical Sciences 7(6), 2010, 16–25.

9. Harrison, A. P. and Turfa, J. F. ‘Were natural forms of treatment from Fasciola hepatica available to the Etruscans?’, International Journal of Medical Sciences 7(6), 2010, table 1.

10. Harrison A. P. and Bartels, E. M. ‘A modern appraisal of ancient Etruscan herbal practices,’ American Journal of Pharmacology and Toxicology 1(1), 2006, 21–24.

11. Guarrera, P. M. ‘Traditional antihelmintic antiparasitic and repellent uses of plants in Central Italy,’ Journal of Ethnopharmacology 68, 1999, 83–192.

12. Macintosh Turfa, J. Divining the Etruscan World, Cambridge, 2012, 155.

13. Baker and Rasmussen 2000, 184.

14. Lippi, M. M. et al. ‘Archaeo-botanical investigations into an Etruscan farmhouse at Pian D’Alma (Grosseto, Italy),’ Atti della Soceità Toscana de Scienze Naturali de Pisa Memorie. Series B 109, Pisa, 2002, 159–165.

15. Columella, De Re Rustica, I, 1, 5. trans. H. B. Ash, London, 1993.

16. Columella, De Re Rustica, I, 1, 5. trans. H. B. Ash, London, 1993.

17. Piny, Naturalis Historia 17, 199. trans. H. Rackham, London, 1971.

18. Columella, De Re Rustica 3, 17, 4. trans. H. B. Ash, London, 1993.

19. Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 15, 702, b. trans. C. B. Gullick, London, 1957.

20. Gran-Aymerich, J. and MacIntosh Turfa, J. ‘Etruscan goods in the Mediterranean world,’ in MacIntosh Turfa 2013, 395.

21. Columella, De Re Rustica 2, 13, 1. trans. H. B. Ash, London, 1993.

22. Varro, De Agri Cultura 1, 2, 25. trans. W. D. Hooper and H. B. Ash, London, 1979.

23. Rohner, D. D. ‘Etruscan domestic architecture,’ in Hall, J. F. (ed.) Etruscan Italy, Utah, 1996, 120–121.