Roman Gardens

The Romans originated from the Latin peoples of Latium in Central Italy, over time they conquered all of their near neighbours, including the Etruscans, and the increasingly powerful city of Rome grew to dominate all of Italy. The traditional founding of Rome was said to have occurred c.753 BC. As previously mentioned Rome was ruled by Etruscan kings (616–510 BC), but after the deposition of the last king the Roman people voted to establish a republic which lasted until Augustus took power in 27 BC. Over centuries the Roman Empire expanded and eventually conquered all the lands around the Mediterranean Sea. Provinces were formed from Hispania (Portugal and Spain) in the far west to Syria in the east, and from northern Britannia to Africa (the northern part of Africa). The Roman Empire finally ended in AD 476 in the west, but continued longer in the eastern provinces under the aegis of Byzantium. However, the Roman way of life continued in north Africa until the Arab Invasions of the 7th century AD.

Evidence for gardens during the long period of Roman rule is enhanced by the wealth of Classical literature that has survived, and by a large number of sites discovered by archaeology. Most of all, we are very fortunate that the catastrophic volcanic eruption of Vesuvius (in AD 79) covered the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum with a thick blanket of ash and pumice, thereby preserving a time capsule for posterity. Here studies could be made on all facets of the Roman way of life, including their houses and gardens.1 This vital information can be compared with material found elsewhere in Italy and from Rome’s provinces.

The Roman Hortus and agri-horti-culturalists

By at least the 2nd century BC a Roman estate and garden was called a hortus (plural: horti); Cato was the first known person to use this term. This word has given rise to our own word Horticulture meaning the culture of the Hortus. In the early days of the Roman Republic the hortus garden was primarily a utilitarian area mostly used for growing vegetables and herbs, but it also included fruiting trees.

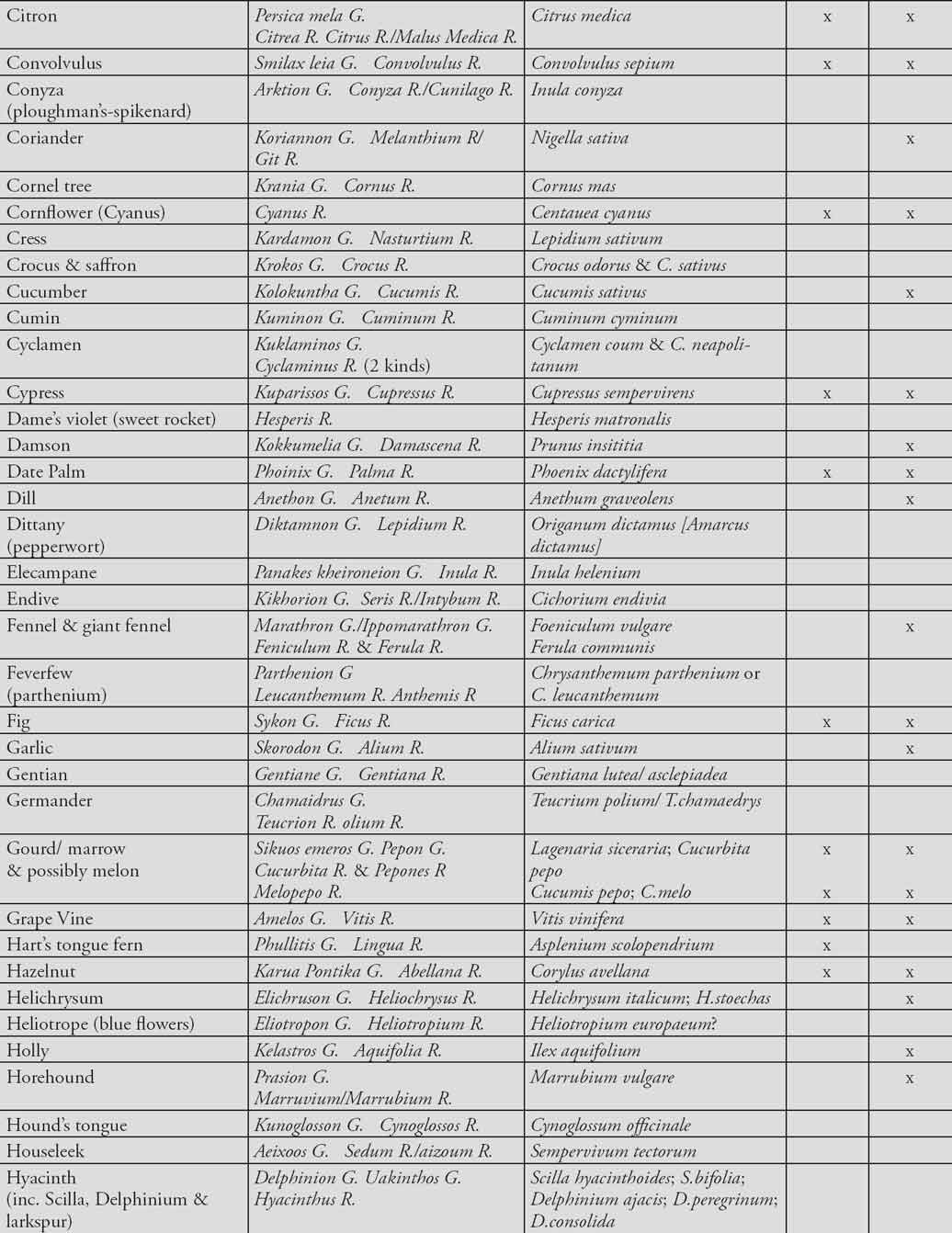

We are very fortunate that four Roman agricultural/horticultural manuals survive. Although these works are primarily on farm management and husbandry they also include sections devoted to arboriculture and the culture of the hortus as part of the farm and villa estate. The earliest was written by Cato (2nd century BC), then Varro (c.36 BC), Columella (c.AD 60) and Palladius (4th century AD). Cato’s manual De Agri Cultura is brief and succinct but is very informative of early practices. Varro’s Rerum Rusticarum (on rustic matters) also gives advice on profitable occupations such as bee-keeping, the management of fish stocks, aviaries and game preserves. In the process he gives examples where these can be made into decorative elements in a garden. Columella, who was a farmer from Gades (Cadiz in Spain), compiled a very thorough manual on all aspects of agri/horti-culture which extended to twelve books. Book 10, dealing specifically with gardens, was written in verse. Columella’s great work was used extensively in the later manual De re rustica written by Palladius.

Pliny the Elder also describes agri-horticultural practises. He compiled a great encyclopaedia on Natural History of which books 12–27 concerns plants, their origins, habits, cultivation and uses.2 His prodigious work is the most informative on Roman gardens. His nephew, known as Pliny the Younger, wrote numerous letters, some of which describe gardens.

Roman deities connected to gardens

The Romans were a very superstitious people and they had numerous deities. When they conquered another city or region, they tended to amalgamate the local deities into their own pantheon, partly because the Romans feared upsetting any deity that could turn against them. Therefore the Romans absorbed Voltumna from the Etruscans, in the process his name changed to Vertumnus,3 his functions in the Roman world are mentioned below. Demeter, Gaia and Herakles originated from Greece, they respectively became Ceres (the goddess of cereal crops), Tellus (the Mother Earth goddess) and the latter was re-named Hercules.

After prolonged exposure to Greek culture we can identify other Roman deities that had a Greek counterpart, but often foreign deities underwent an evolutionary change during the process of Roman assimilation. The pre-existing Roman goddess Minerva took on several attributes of the Greek Athena; Juno is like Hera; Mars the god of war is similar to Ares but has a link to agriculture; Bacchus the ever popular god of wine takes over from Dionysus, etc. Over time many Greek myths were so well known and universally accepted that they became woven into the pre-existing Roman pantheon, and often then further embellished. One such is the Greek Cronos who the Romans believed had fled from Greece to Latium in Italy, but once there was known as Saturn. Saturn was in fact an ancient Italic god (origins otherwise obscure). To the Romans he was credited with bringing the art of agriculture to Italy.4 He was commonly known as ‘the sower’. Saturn is usually shown as an old man wearing a veil over his head and a sickle or scythe in his hand. His great feast day was celebrated with much merriment in the Saturnalia on 17–23 December.

FIGURE 84. Venus, the prime Roman deity associated with the garden’s fertility, accompanied by cupids and her sacred flowers roses. Demi-lune mosaic, Macktar Museum, Tunisia.

Bacchus merged with Liber the old Italic male god of fertility. Bacchus was forever associated with wine and merry making, therefore his sacred plant was the vine often shown with large bunches of grapes. His symbol was either vine leaves, a bunch of grapes, or a wine drinking cup. Before a feast a libation of wine would be poured to honour the god. Bacchus retains Dionysus’ links to the theatre and therefore theatre masks were also used as an allusion to this god.

Venus was the most important of all the Roman garden deities, she was an ancient Latin goddess who was noted as a ‘protectress of the garden.’5 Venus was primarily concerned with the garden’s fertility, but increasingly she became associated with man’s fertility after her syncretism with the Greek Aphrodite. Venus was known for her great beauty and her capacity for pleasure; her associates are the three Graces. Her sacred animal was a hare (and the rabbit). Of the birds the dove, swan and sparrow were sacred to her, and her sacred flowers were the rose and myrtle. The apple also became a symbol of the goddess after she was awarded one as a prize in the mythical beauty contest between herself, Juno and Minerva.

Flora was originally a Sabine (Italic) goddess of Spring and flowers, and all blossoms; she was introduced to Rome in their earliest days. The Roman poet Ovid wove a Greek-style myth around her.6 He recounts how after her union with Zephyrus (the west wind) Flora’s breath clothed the ground and the trees with flowers. Flora was given eternal youth and thereafter she cared for young people in the flower of their youth. She was generally worshipped by all who wanted to ensure that flowers would blossom on their trees, and on their vegetables, herbs and crops, as well as garden flowers. Flora had a festival of her own, the Floralia, which lasted 6 days, 28 April–3rd May. During the rather licentious festival every man and beast wore garlands of flowers, mostly of roses. In art Flora is represented bedecked with flowers.

Pomona was a Latin goddess of fruit trees, she had no Greek counterpart. Her name derives from the Latin poma meaning fruit, the pomarium being a fruit-garden or orchard. Her role was in the care of fruit trees; from their cultivation, welfare and fruit gathering to grafting and pruning. Ovid weaves a wonderful myth about how Pomona was a young virgin who spurned all male advances, until Vertumnus finally wooed her after trying numerous disguises.7 Vertumnus’s name is said to have come from the verb vertere, which means to turn or change, and this partly explains his ability to change shape and guises. He also presided over the change of the seasons and horticulture. After their union Vertumnus takes on many of Pomona’s attributes. They are both represented as figures carrying fruit (either in a basket or by holding them in the folds of their drapery) while in their other hand is a pruning hook, which serves as a reminder of their craft. Over the centuries a certain amount of syncretism took place, and we find that both Flora and Pomona were later absorbed into the cult of Venus.

Priapus took over the role played by Vertumnus, and the two minor gods Mutunus and Tutunus. Mutunus and Tutunus (the two are usually grouped together) were ancient Roman phallic gods who could ensure fertility; and their emblem, the phallus, was a potent symbol used to avert the evil eye of malice and jealousy. The Eastern Greek god Priapus was first worshipped at Lampsacus (northern Turkey) but his cult spread through Greece during the Hellenistic era and from there to Rome. He was said to have been the grossly deformed son of Venus and Bacchus who was abandoned soon after birth. He was taken to be exposed on the mountains, but shepherds took pity on him and reared him; partly because of this Priapus was known to be a rustic god. His huge phallus ensured his association with procreation and fertility but was the cause of numerous ribald poems; eighty of these Latin verses were collected in the Priapeia dated to the 1st century AD. In Italy this rustic god took over the care of vegetable gardens and orchards. All owners of produce gardens would put up a wooden statue to represent Priapus who would then protect their garden, as long as he was given all due offerings and prayers. He was often depicted as a grossly ithyphallic figure brandishing a pruning hook in one hand, both in recognition of his potent powers of fertility and in the art of horticulture. These symbols/weapons were also used to avert the evil eye and to scare away destructive birds from crops, and most importantly to stop or deter potential thieves from stealing produce from the garden. Humorous poems by Martial and others highlight the dangers of owning a wooden statue.

In Spring I am worshipped with roses, in autumn with apples, in summer with corn-wreaths, but winter is one horrid pestilence for me. For I fear the cold, and am apprehensive lest I, a wooden god, should in that season afford a fire for ignorant yokels.8

But there was potentially a greater danger in possessing a marble one which could be stolen. In both cases the owner would be vulnerable if left without a Priapus to care and watch over their garden. Priapus was later included in the Bacchic entourage and therefore was often crowned with vine leaves. On occasion he wears a crown of wheat ears, or spikes of rocket flowers which were sacred to him. His sacrificial animal was the ass, which was known to be a lusty animal. A Roman myth explains an alternative reason for his association with the ass. Apparently Priapus lusted after a nymph called Lotis, and one day decided to creep up to her while she was sleeping. An ass brayed and woke her just in time and she fled. To ensure her protection the gods transformed Lotis into a lotus tree. This would be the southern Nettle Tree (Celtis australis) a very elegant tree of the elm family that was a Roman introduction to Italy from the north African provinces. It produces edible berry-like fruit and was considered highly garden worthy.

The Romans had a surprising number of minor divinities that presided over all manner of events. Before embarking upon a task, a prayer and offering to a particular god would have been required. This is even more evident for agricultural and horticultural tasks, but considering that the Romans initially sprang from a rural community, and traditions have deep roots in the countryside, it is perhaps understandable. We find that there was a deity for almost every stage of preparing plant beds, and for each stage of plant growth. For instance Proserpina was in charge of germinating seeds, Seia for looking after it in the ground, Segetia while it was ripening, Nodutus was in charge of the joints and knots of the stems (he was generally known as the knotted one), and Tutilina when the crop was harvested and stored (she was also known as ‘she who keeps safe’). The poet Servius names some that were mainly applicable to agriculture but would also have been invoked for vegetable plots:

It is quite obvious that names have been given to divine spirits in accordance with the function of the spirit. For example, Occator was so named after occatio (harrowing); Sarritor, after sarrito (hoeing); Sterculinus, after stercoratio (spreading manure); Sator after satio (sowing).9

By the 1st century BC, one of the great Roman agriculturalists (Varro) provides a definitive list of deities that he says, would be advisable for all husbandmen to invoke. They are all paired, often with a male and female counterpart, and he usefully gives the reasons for their inclusion:

First, then, invoke Jupiter and Tellus, who, by means of the sky and the earth, embrace all the fruits of agriculture; and hence, as we are told, that they are the universal parents, Jupiter is called ‘the Father’, and Tellus is called ‘Mother Earth’. And second, Sol and Luna [the sun and the moon], whose courses are watched in all matters of planting and harvesting. Third, Ceres and Liber, because their fruits are most necessary for life; for it is by their favour that food and drink come from the farm. Fourth, Robigus and Flora; for when they are propitious the rust will not harm the grain and the trees, and they will not fail to bloom in their season; wherefore, in honour of Robigus has been established the solemn feast of the Robigalia, and in honour of Flora the games called Floralia. Likewise I beseech Minerva and Venus, of whom the one protects the oliveyard and the other the garden; and in her honour the rustic Vinalia has been established [on 19 August]. And I shall not fail to pray also to Lympha and Bon Eventus, since without moisture all tilling of the ground is parched and barren, and without success and ‘good issue’ it is not tillage but vexation.10

The Romans always feared a failed harvest; so all measures possible were taken to avert this. Therefore in rural communities these rustic deities held sway, and accordingly altars where sacrifices were made would be set up on every farm and villa estate. Gardens in urban sites are still essentially places where plants are grown, so this is another area where we find altars placed so that the household could perform all their necessary rituals.

Sacred gardens

The earliest record of altars in a rural sacred enclosure dates back to 250 BC, in the bronze tablet from Agnone that was written in Oscan (an anc. Italian language). The deities worshipped here were: Ceres, Flora, Genita, Hercules, Lympha, nymphs, Prosperina, and possibly Venus.11 We hear that shrines and altars were built on country estates, Statius mentions a small shrine of Hercules in the grounds of his friend Pollius Felix. After a sudden rainstorm his guests and their garden furniture couldn’t all fit into it so he resigned himself into building a larger temple for the god!12 In cities space is more limited, but at Alba Fucens, an ancient city in central Italy dating back to the 3rd century BC, a shrine dedicated to Hercules was given a large rectangular sacred precinct. The central part appears to have been tended as a garden, but no botanical studies have been made here. We can however speculate whether this vast space contained a sacred grove with plants specific to the god because Pliny the Elder mentions that in some cases plants associated with certain gods were planted around their respective temples: ‘the chestnut-oak to Jove, the bay to Apollo, the olive to Minerva, the myrtle to Venus, the poplar to Hercules.’13

Archaeological evidence for sacred gardens

A possible sacred grove (a nemus) has been discovered in the precinct of the Temple of Juno at Gabii which was rebuilt in the 2nd century BC. Here archaeologists found three rows of rock-cut tree planting pits in the north-east corner,14 but in the dry conditions of late summer a number of matching dark green squares were visible making a pronounced contrast with the parched grass within the precinct. The deep pits had kept the grass moist, and made them quite clear, showing that the three rows of tree plant pits also continued along the north side of the precinct.15 A total of 27 pits were revealed, 24 in a quincunx-like formation. Planting trees in a quincunx (spaced out like the number five on a dice with one in the middle) was recommended by Roman agriculturalists so that the trees would have sufficient root space; they would create a more pleasing diagonal view and from ‘whatever direction you look at the plantation a row of trees stretches out in a straight line.’16 Rock-cut plant pits have recently been discovered in the enclosure of the Temple of Venus at Pompeii along with a series of terracotta plant pots,17 and evidence suggesting a sacred grove was also discovered in the sacred precinct of the East Temple at Thuburbo Maius (in modern day Tunisia).18 Here a row of root cavities revealed the presence of the former trees. The trees had been spaced 50–70 cm apart.

FIGURE 85. Detail of a sacrifice before an altar and statue of a goddess, from a mosaic depicting rural tasks of the calendar year, from Vienne, now in St Germaine-en-Laye, near Paris.

In Rome fragments of an ancient map of the city engraved on marble (dated c.AD 200) was found to give details of a number of buildings and some of these were temples, each located in a rectangular sacred enclosure. Two of the temples on this Severan Marble Map were the Adonaea (for the worship of Adonis) and the Divus Claudius (a temple dedicated to the deified Emperor Claudius).19 For both of these a series of dots and dashes within the garden space indicated the ancient planting scheme. These rare examples give the impression of a sacred grove. For the latter there were four rows of lines on three sides of the rectangular garden space and seven rows on the fourth side. The lines rather than dots have been interpreted as indicating a series of topiary hedges. For the Adonaea there were four rows of dots signifying trees, and a symmetrical pattern of four broken lines and plant beds on either side of a centrally placed elongated water basin.

Rural gardens

At Boscoreale, a rustic Roman villa (villa rustica) uncovered from the same volcanic fallout that covered nearby Pompeii, archaeologists have discovered that the land surrounding the villa was used to grow vines; but there was also a hortus, located close to the villa. This was customary partly so that valuable produce and beehives could be protected more easily; horti were usually enclosed by a hedge or ditch to keep livestock away from tasty produce. Within the hortus at Boscoreale plant beds were clearly defined; around each bed soil had been heaped up into a ridge (a method mentioned by Pliny the Elder) so that when watering the bed the ridge would prevent precious water from seeping away from the plants being tended. A cistern/well had been sited close by so that the gardener did not have to go far to fetch a bucketful of water. Rustic gardens were really designed to provide enough to make the family self-sufficient, but as Virgil’s delightful poem about the old man from Tarentum shows a simple rustic garden could also have a space somewhere to include a few flowering plants too.

he laid out a kitchen garden in rows amid the brushwood,

bordering it with white lilies, verbena, small-seeded poppy.

He was happy there as a king. He could go indoors at night

To a table heaped with dainties he never had to buy.

His the first rose of spring, the earliest apples in autumn …20

Poppy seeds would be harvested to sprinkle on top of newly made bread. Normally the womenfolk of a rural villa would weed the hortus between doing chores in the house, stray finds of lost hairpins in plant beds confirm this.21 It was however, the duty of the Matrona (mistress and housekeeper) of the house to ensure that the household was sufficiently provisioned from the hortus.22 Men would perform the heavier tasks in the garden, orchard and field.

An interesting poem (an extract from a less obscene text in the Priapeia (51)) gives an indication of the plants that could be present in a rustic hortus that was undoubtedly carefully watched over by the god Priapus. In this case he vigorously complains about the thieves coming into his domain:

The fig tree here is no better than my neighbour’s, nor are the grapes such as goldenhaired Arete gathered [she was the wife of the mythical Alkinoös]; nor are the apples meet to be the produce of the trees of Picenum. Neither is the pear, which at such hazard you try to pilfer; nor the plum, more mellow in colour than new wax, nor the service-apple which stays slippery stomachs. Neither do my branches yield an excellent mulberry, the oblong nut, [a filbert], nor the almond bright with purple blossom. I do not, more gluttonously, grow divers kind of cabbage and beet, larger than any other garden trains, and the scallion with its ever-growing head; nor think I that any come for the seed-abounding gourd, the clover, the cucumbers extended along the soil, or the dwarfish lettuce. Nor that any bear away in the night-time lust-exciting rockets, and fragrant mint with healthy rue, pungent onions and fibrous garlic. All of which, though enclosed within my hedgerow, grow with no sparser measure in the neighbouring garden, which having left, ye come to the place which I cultivate, O most vile thieves …

There were always rustic villas and farms in the countryside, but by the late 2nd–1st centuries BC we find that some grew into large country houses that were increasingly embellished with decorative elements. Large villa estates tended to grow into three distinct groups of buildings. These were: the rustic portion that still contained a hortus rusticus; then there was a storehouse the villa fructuaria; and there would now be a separate house for the owner, a villa urbana which was furnished to a higher standard. The villa urbana often included an ornamental garden. Cicero, the great statesman and lawyer, indicates when this development began when he mentions that in his grandfather’s lifetime the family home was small, but during his father’s occupancy it was ‘rebuilt and extended’ into a villa urbana.23 An example is the 1st century BC villa complex at Sette Finestre, near Cosa, where the three parts of the villa have been identified together with at least three enclosures for horti.24 The walls of the main garden were embellished with small turrets with rows of niches at the top of each one; it has been suggested that they mimicked the town walls of a town, or alternatively they may have served as a series of miniature dovecotes (in Latin a columbarium).

The change of villa design was partly influenced by an increase in wealth stemming from Roman conquests in Sicily and the east. Booty brought back to Rome after these conquests included sculpture that was sent to beautify public buildings and these indirectly triggered a desire to beautify people’s own home and garden as well. One of the returning generals, Lucullus, was especially influential in this movement because he partly emulated the opulence of eastern rulers and his subsequent hedonistic lifestyle became proverbial. Around 60 BC he built a grand villa with landscaped gardens on the Pincio, one of the hills overlooking Rome, this was the first project on such a scale, and its beauty was greatly admired, although censured by some. The new garden form contained elements derived from Persian and Hellenistic paradeisoi, those pleasure gardens and game preserves of eastern rulers, as well as elements borrowed from the sacred groves of Hellenistic Greece. Many Romans aspired to own something grand and they tended to emulate some of these features in their own villa/house and garden, albeit on a smaller scale. Gardens within the estate of a villa urbana could be extensive, but there were also smaller areas of greenery in courtyards inside the villa itself, and these would be closer to what was possible in an urban domestic garden. Pliny the Younger reveals in one of his letters how one of his internal gardens was shaded by four plane trees and in the centre a fountain played in a marble basin.25 Such details can now be matched by archaeology (see below). Internal gardens were on occasion termed a viridarium, meaning a place of greenery.

Urban domestic gardens

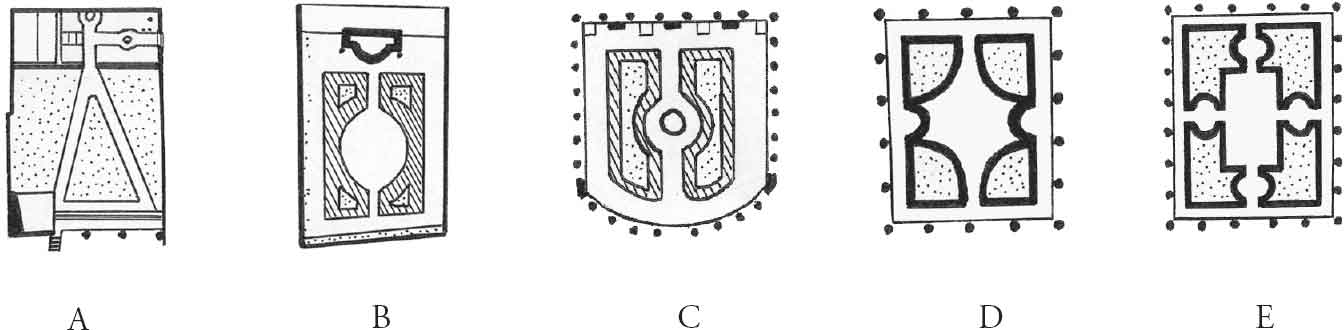

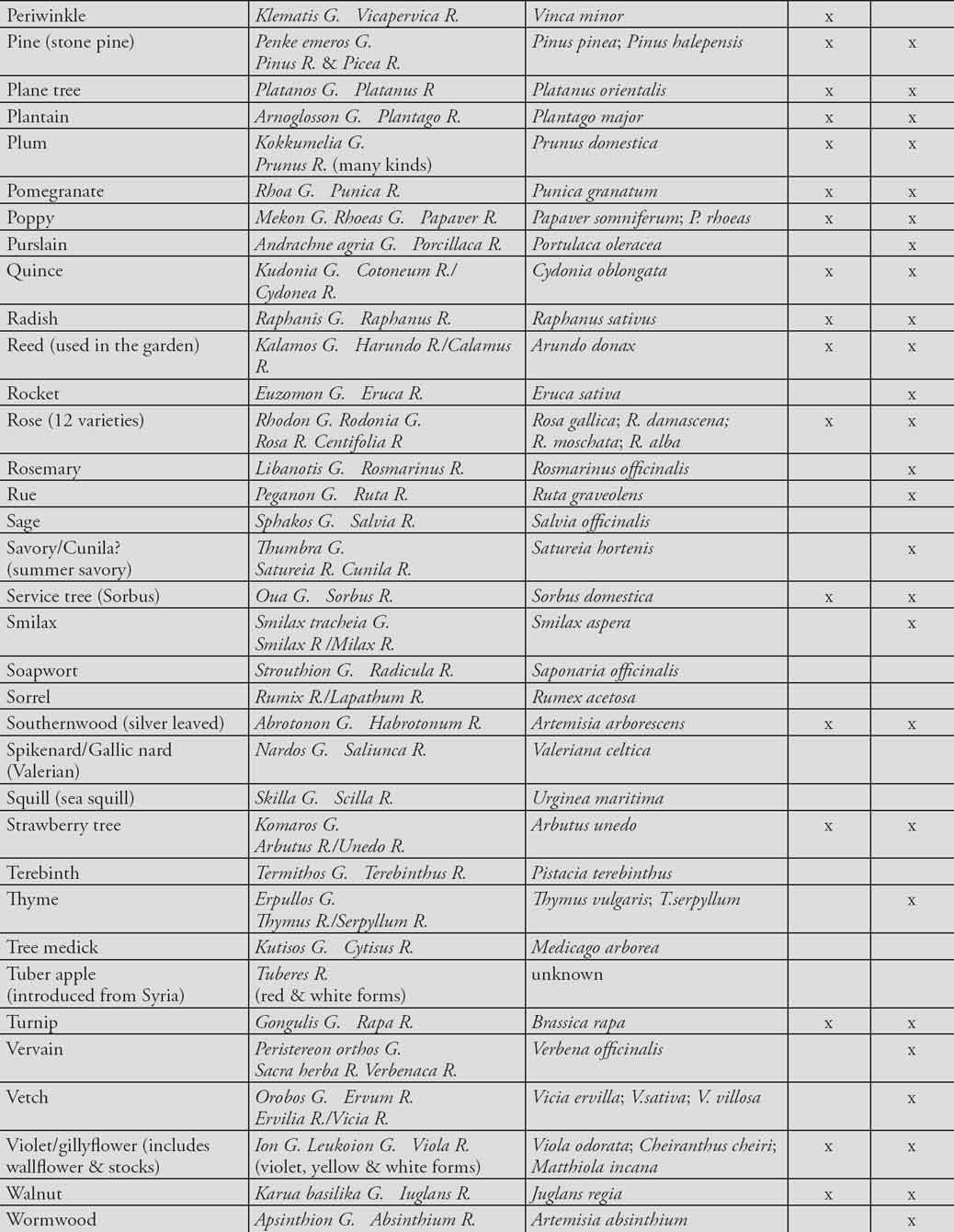

In urban situations there was less space and houses were fitted cheek by jowl in blocks in a grid of streets. But many Romans, unlike the Greeks, opted to have a garden of some kind within their allotted plot. The earliest Roman houses (a domus, pl. domi) to incorporate a garden have been found at: Cosa, a Roman colony in Etruria; at Fregellae a Latin city south of Rome, and at Pompeii. At Cosa the 3rd century houses were each given a hortus that was roughly equal in size to the house.26 The early domi found at these sites are what is often termed an atrium style house. The first phases of this early form (Type A) dates back from the 4th to the beginning of the 2nd century BC.27 Atrium-houses were usually axial in plan, and often comprised a passageway leading into an atrium hall. The partly open roof above the atrium was inclined inwards so that falling rainwater could be captured in the impluvium basin below. From there rain water was channelled into an underground water storage cistern. Water could then be drawn for the family’s needs and to water plants in the garden when necessary. The garden or hortus was usually sited to the rear of the house and would be as large as space would allow; for security there would be high walls around the garden.

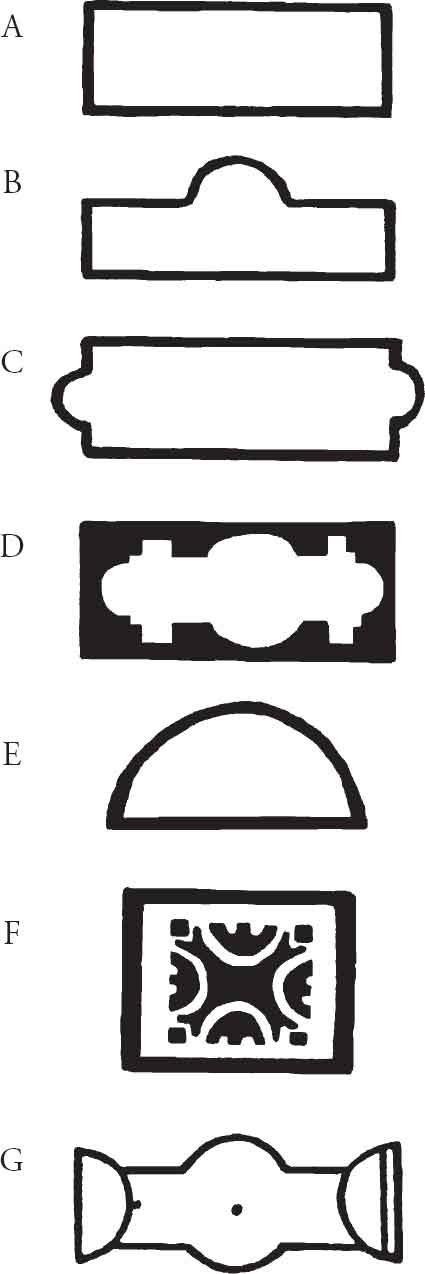

FIGURE 86. Plan showing three different forms of a Roman house (domus) with garden.

Over the centuries the layout of the Roman domus changed after eastern elements – such as a colonnaded peristyle – were incorporated into the house plot (Type B). This had the benefit of allowing more rooms to be added around the peristyle. The Romans again preferred to cultivate this open space as a true garden. This popular style appears to have come in fashion during the 2nd century BC.

FIGURE 87. Full-scale reconstruction of the peristyle garden at the House of the Vettii, Pompeii, which was a rare opportunity to appreciate the spectacular effect of the jets d’eau, and the full complement of the garden’s sculptural furnishings. Made for the Il Giardino Antico Da Babilonia A Roma 2007 exhibition in Florence.

In the Type C domus the garden itself became the heart of the house. This type is more often found outside of Italy, and there were a number like this in Roman Britain (such as at Gloucester, Caerwent and Silchester).28 There are a few Type C houses at Pompeii, so this form can be said to date from the 1st century AD at least, but type A and B were still current elsewhere.

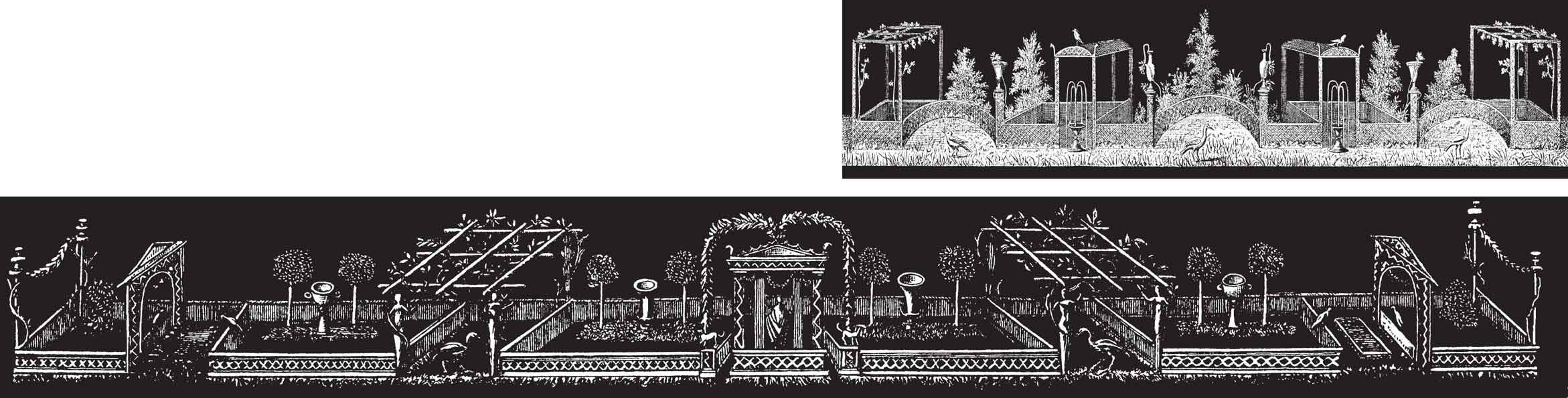

The House of the Vettii at Pompeii displays many features that you might find in a Roman peristyle garden. Ideally, as here, the garden is surrounded by a peristyle comprising four porticoes, again enabling rainwater to be collected from the roof. In some houses there was insufficient room for a complete peristyle so two or three porticoes were built instead (as in the House of the Tragic Poet at Pompeii). Sometimes the remaining solid garden walls had applied stucco to make imitation columns and were painted so that the illusion of a peristyle was created. On these occasions the spaces between the imitation columns of the pseudo-peristyle could be painted to appear like a garden or a landscape, or even as a window through which you could see a garden beyond. These trompe l’oeil works of art would help to give the impression of a much larger garden area. At Pompeii we can see that even the owners of small dwellings could beautify their home with a garden, even if the only space available was a mere strip.

Other forms of Roman gardens: Public gardens (porticii)

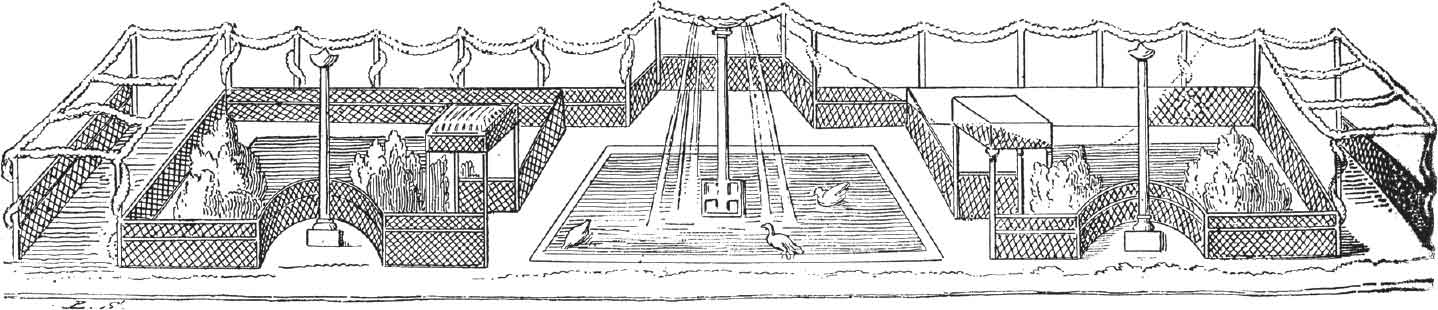

Gardens were created to adorn many public buildings, such as libraries, bath complexes, and temple precincts. Sources suggest that plantations in these gardens were mostly of evergreen shrubs and trees. Public gardens were often enclosed by a large rectangular peristyle, and therefore they came to be known as a porticus (pl. porticii). Pompey the Great was the first wealthy Roman to create a ‘porticus garden’ (in 55 BC) to form a beautifully verdant entrance to the magnificent new theatre that he was building on the Field of Mars at Rome. The porticoes and tall shade trees planted in this garden gave shade from the sun and space for spectators to gather before and after plays. Propertius provides an indication of the appearance of this garden, he says it had an ‘avenue thick-planted with plane trees’.29 He also implied there were two fountain figures beside a pool in this welcoming public area. Martial mentions that the garden of the Porticus Pompei had a nemus duplex (a double grove of trees)30 so the plane trees could well have been placed on either side of the central path that is shown on the relevant fragment of the Marble Map. The garden plan also shows that there were a series of semicircular and rectangular recesses along the margins of the garden to provide seating areas.

We also hear of the Porticus Liviae, a garden that had been donated to the populace by the Empress Livia; the garden walks here were said to be shaded by a huge grape vine that produced large quantities of wine every year.31 Plantations of box were a feature of ‘sun-warmed Europa’, a public garden mentioned in passing by the poet Martial.32 The donation of public gardens was seen as a great act of benevolence, but also it was very good propaganda for the individual concerned. Not to be outdone by Pompey, in his will Julius Caesar left his own gardens to all the citizens of Rome; and later Augustus planted the Nemus Caesarum for public use and also his silvae et ambulationes (woods and promenades) that were created around his mausoleum. Others followed suit, such as Agrippa who donated his bath complex and associated gardens (the Porticus Vipsania) which were said to be planted with laurel bushes.33

The concept of Portico gardens was not confined to the metropolis, several have been found in cities throughout the Roman world. At Italica and Merida in Spain the theatre was provided with an adjacent portico garden, at the latter the garden has now been replanted with trees and green hedges on either side of a wide central path.

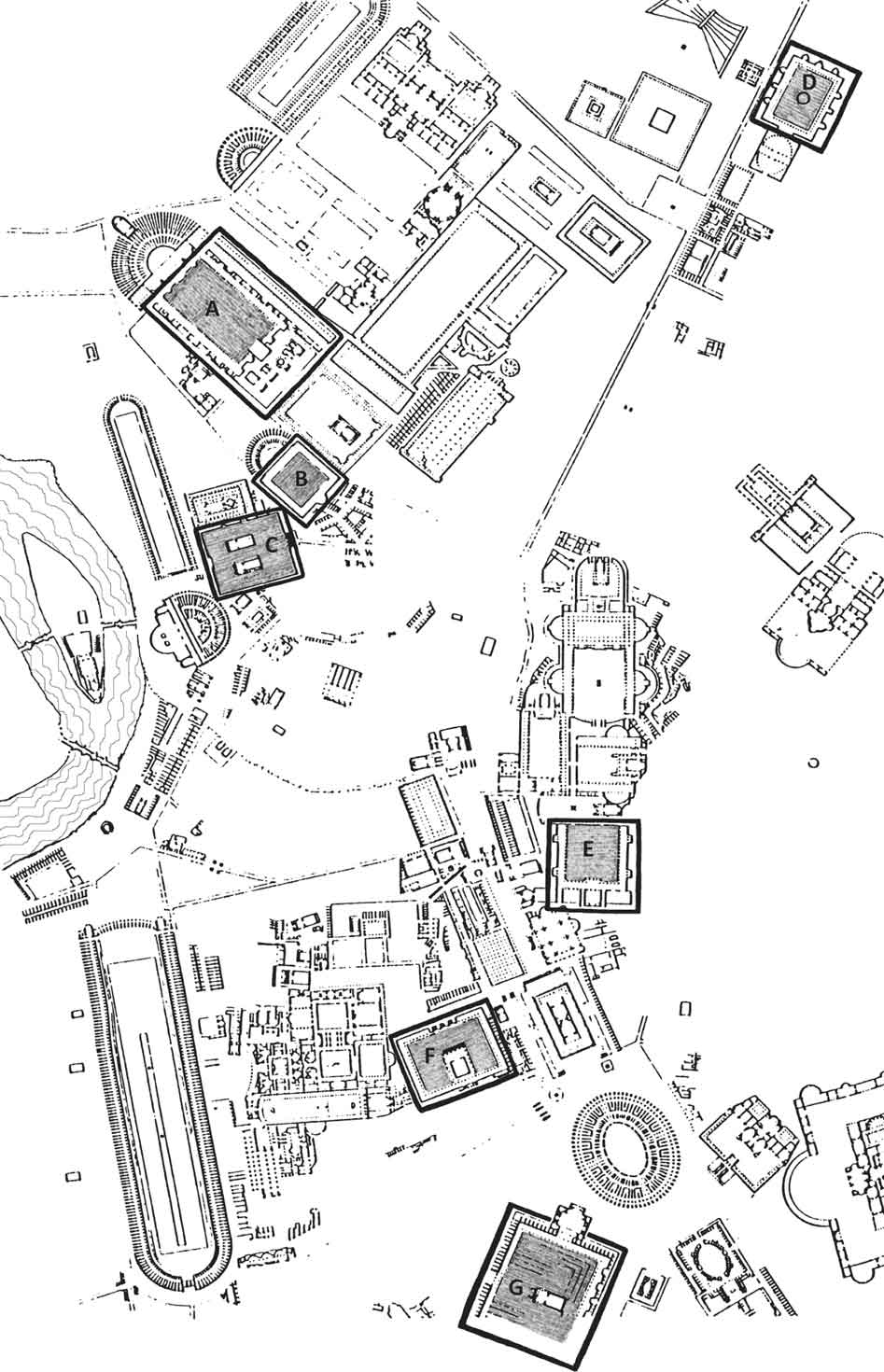

FIGURE 88. Map of central Rome showing the location of several public portico gardens. A: Porticus Pompei, the first such garden built c.55 BC by General Pompey the Great to form a pleasant adjunct to his new theatre building; B: Crypta Balbi; C: Porticus Octavia; D: Templum Soli; E: Templum Pacis; F: Adonaea; G: Templum Divus Claudius, a portico garden surrounding the temple of the deified Emperor Claudius. The Temple of Peace (E) was judged to be the most beautiful building in Rome, aided no doubt by the lush garden forecourt (map after MacDonald 1986, fig. 206).

Corporate gardens and those associated with inns and taverns (tabernae)

Gardens were also created on the premises of private clubs and guilds, as seen at Ostia in the House of the Triclinia, where numerous dining rooms opened onto the porticoes surrounding the garden. The garden of the guildhouse at Tarraco (Tarragona) in northern Spain was highly ornamental with two marble nymph fountain figures besides a pool. Inns and taverns often had an open garden area (a version of our beer gardens) where drinking parties could take place. Virgil tells of an innkeeper whose staff would stand outside and tempt any passerby to sample their wares in pleasant surroundings: ‘There are garden nooks and arbours, mixing-cups, roses, flutes, lyres and cool bowers with shady canes [trellises] … come; rest here thy wearied frame beneath the shade of vines.’34 Such dining establishments have been discovered by archaeology at Pompeii, Ostia and elsewhere.

Market gardens and plant nurseries

Literary evidence for these is provided by Pliny the Elder who mentioned visiting a nursery garden so that he could inspect the variety of medicinal plants growing there. He also discusses how to create a nursery bed, and to make cuttings in plant pots.35 Both Cato and Varro state how useful it would be if market gardens were sited on the outskirts of cities so that fresh produce could easily be brought to a ready market.36 A few Hortuli (the specific term used for market gardens) were located in the more spacious south-east part of Pompeii. On excavation one of these proved to be a commercial garden for growing flowers. Part of the site of the Garden of Hercules was found to have well preserved soil contours showing a network of wide plant beds separated by water channels.37

In the dry conditions of Egypt ancient letters and contracts of leases written on papyri during the Roman period have miraculously survived in the Fayumn area and at Oxyrhychus. Some attest to the existence of market gardens where vegetables were the prime source of income, but we also hear how some gardeners specialised in cucumber growing, or in providing flowers. One letter asked for 2000 narcissi and roses to be sent for a wedding celebration.38 Archaeological evidence for a huge commercial plant nursery has been discovered at Abu Hummus in the Western Delta area of Egypt. 39 The complex dates to the 1st century BC–3rd century AD. Here plants had been propagated from cuttings in clay receptacles. The proprietors had made use of a supply of used wine amphorae and cut them into two halves. The bottom half of the amphora had its pointed end cut off to create a drainage hole, while the upper half of the amphora was inverted so the neck of the vessel could provide a convenient drain hole. An astonishingly huge quantity of used amphorae were found here in numerous rows, stacked carefully beside a path in eight baked-brick propagating bays. Each bay had water channels. To give an indication of the scale of the enterprise each row had approximately 27 amphorae, and there appears to have been four rows on each side of the path in each bay. The portion of the complex uncovered is therefore thought to have held c.4928 amphorae. The staggering quantity of plants being propagated here is not just to supply local orders but has been assumed to be for the export market. When the scions had sufficiently rooted they could have been shipped to Rome or elsewhere. Earlier Ptolemaic papyri from the Zenon archive suggests orders for a variety of fruit trees: apples, apricots, figs, olives, peaches, pears, plums, walnuts, laurels and roses. At times large quantities of trees were requested, such as 200 pear trees, 500 pomegranates, 10,000 vine shoots,40 and there may have been similar orders at the site of Abu Hummus.

Tomb gardens

Tombs were normally located on roads leading out of the city, for reasons of hygiene. Romans aimed to have an impressive monument that would be noticed, therefore they themselves would be remembered. Occasionally rich people would opt to have an adaption of the Hellenistic style cepotaphia, a monumental tomb surrounded by a garden enclosure. A satire by Petronius gives the scenario of a fictitious parvenu freedman Trimalchio discussing his own funerary monument which would include a plot containing fruit trees and vines.41 Usefully, he also suggested how large it would be, which gives an indication of the scale of these plots; it was envisaged to be ‘a hundred feet facing the road and two hundred back into the field’. This would be sufficiently large to provide his shade with the customary offerings in his honour and any surplus produce could usefully provide an income for any heirs. For example a number of funerary inscriptions stipulate that their descendents should give the deceased his customary tipple of wine. In these cases a pipe would be fitted next to the tomb so that a libation could be poured down to sustain his shade (or soul) below. Another inscription asked that profits could be used so that his survivors would offer him roses on his birthday, forever.42 Banqueting facilities were often included in the garden so that family and friends could come out to dine with the departed, and the deceased would be able to retain that vital link with the living.

FIGURE 89. Two miniature frescoes depicting trellis fences forming ‘garden rooms’. Upper from Herculaneum, lower from Pompeii.

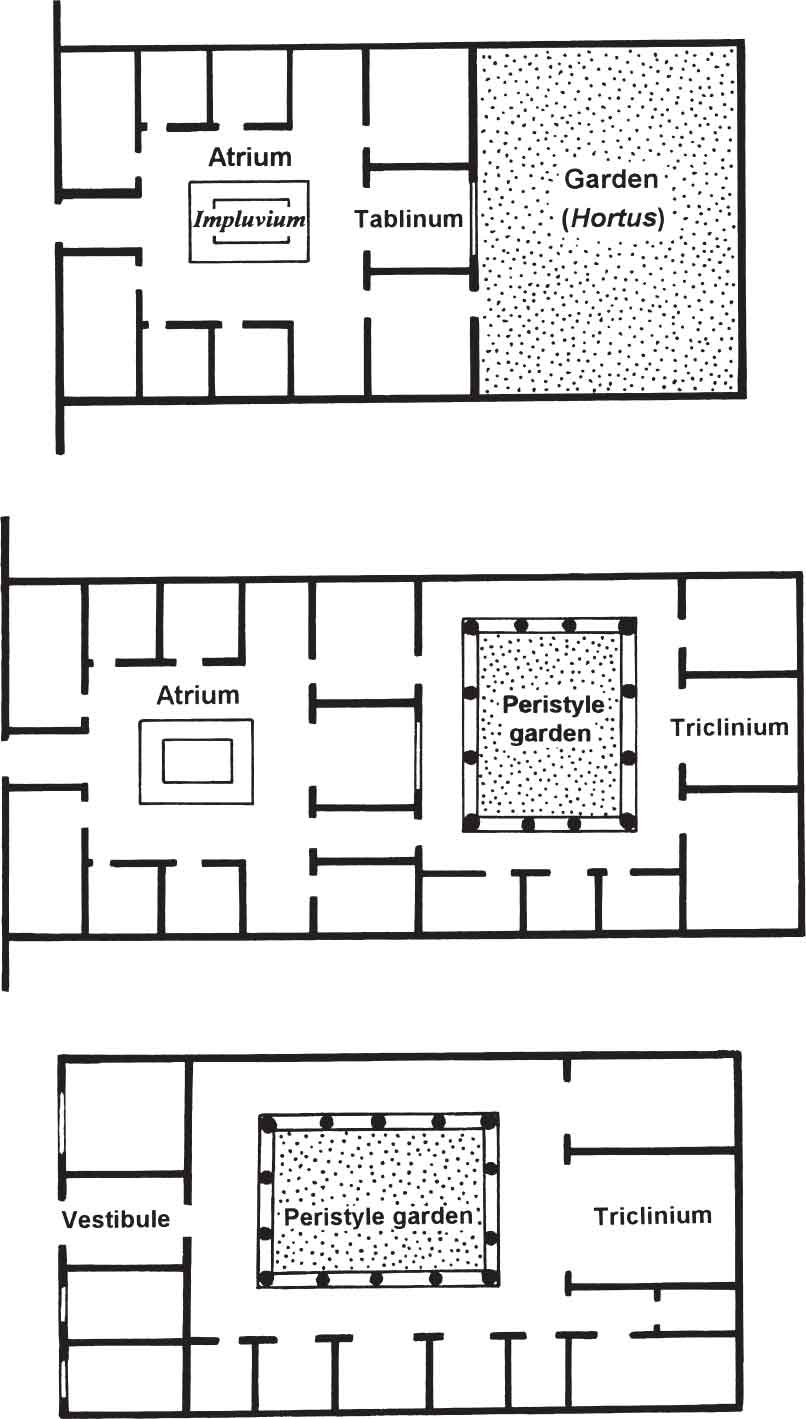

Fresco paintings depicting gardens

Frescoes reveal many aspects of garden art and the key feature is that it is a verdant scene,43 with trees and flowering plants, but many also feature decorative elements that must have been current in gardens of that time. We see trellis fences, decorative low marble walls, fountain bowls in a variety of shapes, and sometimes sculpture in their garden setting. The frescoes on the rear garden wall of the House of the Marine Venus at Pompeii (in situ), and those of Livia’s Garden Room at Primaporta (now in the Massimo Museum, Rome; see Fig. 106) are examples. There seems to be a delight in illustrating their gardens filled with a variety of birds and prized species of plants, but we can also notice that the artist has depicted plants flowering and trees fruiting all at the same time regardless of their season. The scenes may be a real-life representation of a garden, or a desire to depict an ideal garden, but they also invoke a literary comparison. The Romans liked to show their knowledge of classical Greek culture, and Homer’s myths were very popular. In this case the myth where Odysseus describes a mythical never-endingly fruitful, abundant garden belonging to Alkinoös, King of the Phakians is brought to mind, and on occasions the Romans actually compared their own garden with this mythical one.44 So these frescoes adapt this Greek myth into an ornamental Roman ideal. The frescoes certainly show that Romans aimed to nurture a fertile garden.

At Primaporta the Empress Livia had a wonderful cool underground room (for use in high summer to avoid the searing heat above), this room was covered with beautiful garden frescoes, she obviously wanted to be reminded of the greenery and fresh air outside. A low yellow lattice fence forms a dado-like zone around the base of all the walls, and then as if behind this, we can see a low white marble wall comprised of different decorative panels. In the centre of each frescoed wall this low wall forms a recess so that a specimen tree could be displayed to greater effect. As with many Roman frescoes the plants are painted with care and we are able to determine the species depicted, and gain an insight into which plants were cultivated in that period. Clumps of low growing plants are shown in front of the low wall, with mid-height flowers and shrubs behind it, forming an underplanting for the trees and taller shrubs behind. An amazing variety of birds are illustrated in these frescoes (70 in all) some are flying above while others alight on a branch or stand on the edge of the wall and fence; the myriad of birds reinforce the idea that what we are seeing is a welcoming real garden.

A wide range of plants is painted in frescoes, in the House of the Fruit Orchard at Pompeii there were a number of fruit bearing trees (apple, cherry, fig, lemon, pear, yellow and blue plums and peach or pomegranate).45 More decorative species were chosen for the frescoes in the House of the Golden Bracelet. There were laurustinus (viburnum tinus), bay, oleander, dwarf oriental plane trees and palms, strawberry trees, pink flowering rose bushes, variegated ivy, white flowers of feverfew or chamomile, golden flowers of chrysanthemum segetum, white drooping flowers of Solomon’s seal, blue flowers of periwinkle, opium poppy, and white Madonna lilies. In the dado zone there were hart’s tongue ferns, iris and rounded clumps of ivy. Many of these plants are depicted in frescoes elsewhere, and apart from the rose, bay, and pine trees, the most popular perennial plants depicted in garden frescoes were acanthus, and the hart’s tongue fern. Other flowers and bushes can be identified in frescoes such as the grey-leaved aromatic bush of southernwood, in the House of the Marine Venus.

On occasion ivy is shown growing in a mound supported by a reed stick (bamboo had not yet been discovered), some of these feature in a fresco in the House of Ceii and in a dado in the House of the Vettii. This is valuable information on an aspect of Roman horticultural practice that could not be found by archaeology.

Several miniature frescoes illustrate features found in larger gardens, such as wooden arches, or a pergola (in Latin pergula) and trellis fences that formed enclosures.46 The Romans were the first to create ‘garden rooms’, and as these frescoes show the Romans enjoyed creating architectural decorative effects by having semicircular and rectangular recesses to give more variety. A niche would make a perfect backdrop for a special sculptural item or urn fountain bowl. The permutation of Roman trellis design is endless, they were of varying height, however they were usually in a diamond lattice pattern. Several miniature frescoes have been found at Pompeii and Herculaneum, but also at Rome and Alba Fucens.47 In the latter, figures stand under the arched entrance of three long pergulae. In between each pergula there are enclosures edged with green clipped hedges; in the centre of these there is a rectangular blue pool.

Pergolas and trellises could be used to grow vines, and an example is the fresco from Boscoreale (now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York) but they also were used to train roses, ivy, and even gourds (as seen in a 4th-century AD fresco in the Via Latina Catacomb at Rome).

Archaeological discoveries of ornamental garden features

Sadly only the post-holes of a pergola and trelliswork can be discovered by archaeology, the upper portion would have rotted away long ago leaving little trace. So we are very fortunate that frescoes illustrate their appearance, and indicate how the garden space was used. Archaeological evidence for pergulae have been discovered in several Pompeian gardens; a fine example is in the House of Loreius Tiburtinus where the pergulae extend along both sides of an elongated water feature in the lower garden. Root cavities beside each post of the pergulae indicated that vines had once shaded the walkways beneath. However, another house provided evidence for a simple fence (in this case made of reed) that delineated a path in the garden of the House of the Chaste Lovers at Pompeii. The paths were made of hard beaten earth, and showed clearly against the friable dark enriched soil of the plant beds. Garden paths elsewhere were found to be of sand or gravel.

Wooden seating would also have rotted over the centuries leaving perhaps only a stain to mark its former position in the garden, as found at the House of Bacchus and Ariadne at Thuburbo Maius where just the supports were detected. However without further indications the supports by themselves could relate to either three wooden benches or tables, or even a mixture of both.48 The poet Martial mentions how his wooden garden seats had deteriorated badly, so it is perhaps not surprising that many householders decided to have a more permanent garden seat made of stone or marble. Also al fresco dining areas were constructed in gardens, and these were especially favoured in summertime when it would be too hot indoors. They were often shaded by a vine covered pergola to filter the sun’s rays and shade diners reclining on their couches below.

Many examples of masonry outdoor dining couches have been discovered in cities and villas around the Roman world. There were three forms, a biclinium (bi=two, clini=couch) these could be sited in an L shape or facing each other as at the House of the Thunderbolt at Ostia. The triclinium (tri=three) comprised three couches that were usually designed in the form of a U shape; nine diners could fit onto a triclinium each facing inwards when reclining. This was the type most favoured during the Roman period. At least two residents of the excavated part of Vienna (modern Vienne/St Romaine en Gal, France) had a vine covered outdoor triclinium couch in their peristyle gardens; as did an inhabitant at Russellae in Etruria. The third form of dining couch current during the Roman period was the stibadium, which was a large semicircular couch. Often these were provided with a little semicircular water basin where fingers could be washed during meals. A good example is the one found in the middle of a peristyle garden at Italica in Spain; similar couches were even fitted into gardens in North African provinces such as in the House of Hesychius at Cyrene (Libya). In both of these cases a pool was sited adjacent to the couch, perhaps so that dishes of food could be floated on the water’s surface to keep cool, as in a delightful scenario recounted by Pliny the Younger.49

FIGURE 90. Simple reed fences line a garden path in a pattern discovered by archaeology at the House of the Chaste Lovers, Pompeii. A full scale reconstruction of this garden was made for the Il Giardino Antico Da Babilonia A Roma 2007 exhibition in Florence.

At Pompeii more evidence of garden furnishings survive simply because citizens left quickly or were engulfed by the cataclysmic volcanic eruption of Vesuvius. Shrines, altars, sundials, statuary and sculpture were left behind; there was precious little time to save their own lives. It was their misfortune that has aided our knowledge of their daily lives. Complete sculptural collections survive in some houses whereas in most cases elsewhere survival depends on chance, such as if items were thrown into a pool (as at Welschbillig in Germany where 68 herm statues from a decorative wall once lined the pool).50 The Romans admired Greek sculpture and many copies and versions were made (of varying standards) so that those affluent enough could display them in their homes and gardens. Statuary and sculpture were expensive items so owners would site them carefully to capitalise their effect. One of the ideal locations was in the garden where guests would be able to admire them, so many were actually placed in direct line of sight of diners reclining on their dining couches in a grand reception/dining room. Statuary was seen as decorative yet they also embodied the deity portrayed, so they were treated with due respect.

FIGURE 91. Outdoor dining couches. Left: the biclinium; centre: Triclinium; right: stibadium.

FIGURE 92. Beyond the rectangular raised pool are the remnants of a biclinium al fresco dining area and shrine. The two couches are placed so that the diners reclining there could face each other to converse. Mattresses would have made the couches more comfortable, House of the Thunderbolt, Ostia.

The most popular items of statuary found in Roman gardens were statues of water deities (in proximity to water features) or deities closely associated with nature who would be considered at home in the greenery of the garden. Silvanus the god of woodlands sometimes makes an appearance; but the rustic god Pan, and those boisterous woodland revellers the satyrs, were frequent visitors in sculptural form; as were all of the Bacchic entourage. Members included: Ariadne the consort of Bacchus, his drunken foster father Silenus, maenads who were frequently being chased by satyrs, Pan, fauns, centaurs, bacchantes, and Priapus. Bacchic statuary is often humorous, at times perhaps irreverent, but was in keeping with the carefree attitudes of Bacchus himself. Large versions of Bacchic wine cups (a cantharus) were made in marble and these served to form an association with the god in the garden. Many were turned into a fountain, as seen in the beautiful Pompeian frescoes where birds come to drink water at the edge of the bowl.

Statues of Venus were also popular in gardens, her lover Mars (the god of war) was on occasion found in garden contexts due to his liaison with Venus but also because he had a connection to agriculture. It was also no surprise that their mischievous son Cupid was a popular figure in garden statuary. Winged cupids and statues of children, with or without animals were understandably favourite subjects being a reminder of youth.

Certain myths could be re-enacted in the garden in a statuary form: a statue of Hercules could recall the myth of the hero’s exploit in the Garden of the Hesperides. Diana and animals, such as boars and stags, could allude to many Romans favourite sport – hunting; while statues of the Muses and Apollo could foster contemplation and inspiration in the garden.

However, herms were the most popular items of sculpture in Roman gardens. These were simply a bust on a shaft. Cicero owned a couple of bronze herms, but these would have been very costly items and the majority were made of marble. The busts often portrayed the god Hermes (after whom they were named) or a Bacchic figure. Herms sometimes represented an emperor or philosopher, and could even be made in the likeness of a member of the household; they were a very versatile form of ornamentation in the garden. There were even janiform herms: these were co-joined busts that like the god Janus had one face looking forward while the other looked back. The paired faces were sometimes male and female so there might be a satyr and maenad, or alternately the facial features reveal a young and old Bacchus. The latter were the most popular choice for a janiform herm.

Gardens (in Italy and Spain in particular) were adorned with one or more pinakes (sing. pinax); these were rectangular marble plaques placed on top of a short marble post. They were carved on both sides generally with Bacchic iconography, paired theatre masks were favoured. Ornaments were also suspended from the architrave of the garden’s surrounding porticoes, these were oscilla (sing. oscillum). Their name suggests that they would oscillate with a breeze, but in reality these marble discs were too heavy to do this, because on average they were c.30 cm in diameter. Frequently traces of the iron suspension hook is still detectable. Oscilla were also carved on both sides so they would be seen and admired to good effect from the peristyle and from in the garden itself. Gardens would contain more than one oscillum, and if a house had more than one peristyle, as at the House of the Citharist at Pompeii, then as many as twelve could be possible hanging from their porticoes.51 The majority of these decorative items were circular, but there were some small rectangular ones, and some were shaped like a theatre mask, others represented a semicircular pelta. The latter form mimicked the shape of a pelta shield belonging to the mythical Amazons. The most commonly encountered oscillum is a circular or pelta shaped one, and these have been discovered in gardens in the provinces as well as in Italy. Oscilla often feature in the garden frescoes of Pompeii where they hang suspended from a line along the top, or they are shown hanging from an archway in some of the miniature garden enclosure scenes.

FIGURE 93. Terminal busts of a janiform herm. Like the god Janus one head looks forward and the other back. This form can show a combination of young and old faces or male and female, Alexandria Archaeological Museum.

FIGURE 94. An oscillum which mimics the form of a pelta shield carried by an Amazon. There are griffin heads on either side and a palmette on the top, which is the point of suspension. The main scene features a satyr and a pedum stick used by shepherds, Cordoba Archaeological Museum.

FIGURE 95. On a Roman sundial a metal gnomon pointed out the hours on a concave inner surface of a fan-like dial. The length of a Roman hour varied throughout the year therefore the long summer hours were read from the wider placed lines on the lower section, and the shorter winter hours from the upper portion. The curved line crossing over the hours marks the equinoxes, Larino, Italy.

Another item that was specific to this period (although invented by late Hellenistic Greeks) was the sundial. These stone objects usually had a concave dial52 and a metal gnomen that created a shadow pointing to the approximate hour. What better location could you find to be able to read the time of day than a sunny spot in a garden.

Garden pools

The construction of aqueducts to cities, and the diversion of streams to country properties meant that the inhabitants could now add water features to their gardens. Many Romans chose to construct an ornamental pool, although not all were used to contain fish. On occasion evidence for fish keeping was confirmed by finding a row of fish refuges that had been inserted into the side walls of the pool. Some were of stone but many were in fact terracotta amphorae inserted with the neck of the vessel flush with the side wall of the pool, examples of these were found in the rectangular pool of the House of the Triconch Hall at Ptolemais in Libya.

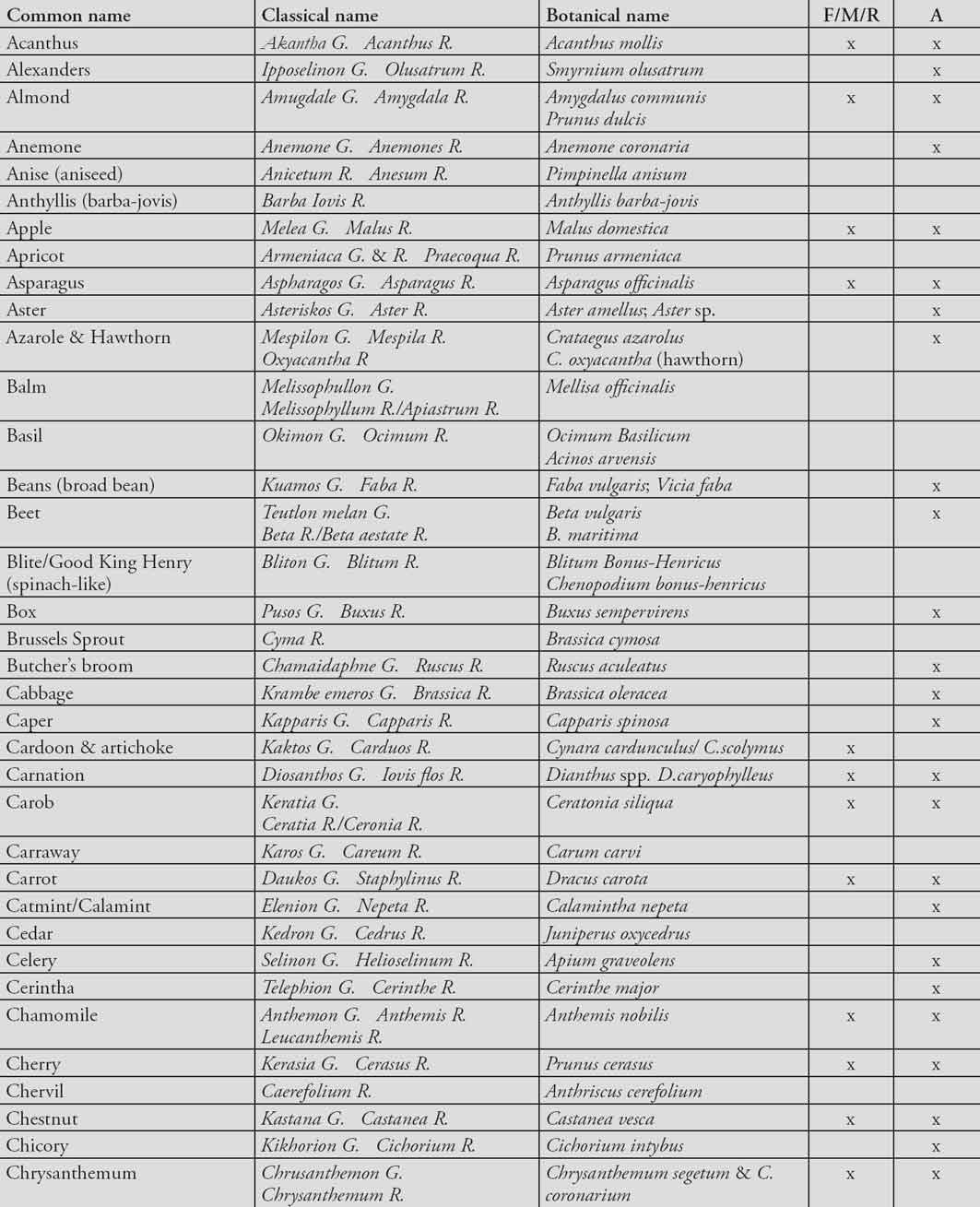

The majority of Roman garden pools were rectangular in shape or semicircular as these shapes were easier to construct. Most were found to fall into seven different types that reflect a change in fashion or taste.53 The simple rectangular pool at Ptolemais was classified as a Farrar Type A. All Roman pools were based on geometric shapes; there was never a desire to have an irregular shaped pool. The interior of pools were sometimes painted blue, or had fish painted on the sides, any movement of the water would then make them look to be swimming about. Another form of decoration was to line the pool with a beautiful mosaic, which could have fish or suitable aquatic scenes (this was particularly favoured in shallow examples of the semicircular pools of Farrar Type E).

FIGURE 96. A row of terracotta amphorae were used to provide fish refuges in a Type A rectangular pool at the House of the Triconch Hall, Ptolemais, Libya.

FIGURE 97. Typology of Roman pools.

In some gardens the gutters around the peristyle were replaced by a narrow elongated pool that ran continuously around three sides, leaving one open for access, this form was favoured at Vienna (Vienne in France) but less so elsewhere. More interesting shapes of pool were attempted and we find that some had either semicircular niches added to the exterior of the rectangular pool (Types B and C), or they had a combination of semicircular and rectangular niches made in the interior of the pool (Type D). More complex water basins appear to have had little islands of greenery in their midst (Type F). This was achieved by constructing several watertight caissons that could be filled with soil and planted. A number of houses in Conimbriga, Portugal, have a pool of this kind, each with differently shaped caissons. At the House of Swastikas the rectangular water basin had four symmetrically disposed quarter-circle islands of greenery, while the House of the Water Jets had six. A later style saw the introduction of intercommunicating pools (Type G) and is typified by the three pools seen in the peristyle at the Villa of Piazza Armerina, Sicily.

FIGURE 98. Restored garden with a gutter water-basin running around three sides. The clean lines and the blueness of the water give a wonderful indication of how they once might have appeared, House of the Five Mosaics, Vienna (modern Vienne/St Romain-en-Gal, France).

FIGURE 99. A water garden, Type F pool. Water-tight caissons allow islands to be planted inside the pool; 400 water jets create a stunning spectacle, House of the Water Jets, Conimbriga, Portugal.

FIGURE 100. Three intercommunicating pools with central fountain in the garden of the Villa at Piazza Armerina, Sicily (photo: M. Morley).

Fountains and nymphaea

Water could be brought to the pools by employing a fountain fed by gravity. Single or multiple fountains played into pools. At the House of the Water Jets at Conimbriga there were 400 small bronze fountain jets, these were sited around the rim of the water basin and around each of the ‘islands’ to make quite a spectacle, and what is astounding is that they are still in working order today. The jets make just a gentle arc because of low water pressure, but the overall effect is amazing; and that was the intention. Romans wanted and needed to display their wealth, and this is another method of doing so. At times you see a conspicuous consumption of water (for fountains) simply to tell their world that they were important influential people.

Water outlets were often fashioned of bronze, some were plain as at the House of the Water Jets, but elsewhere ones fashioned in the shape of a dolphin or bird have been found. The desire for ornamentation was great, and we find that a lion’s mask, or head of a fluvial deity, were very popular devices used to direct water from a wall mounted fountain. Marble statues were bored through so that water could pour out of the mouth of an animal; or alternatively water would be made to trickle out of an urn or wineskin carried on the shoulder of a figure, the viewer was meant to interpret this as wine pouring. The tinkling sound of water enlivened a garden and fountains were positioned carefully to maximise their effect. Even if you only had a small light-well court it could be made attractive with a central fountain. One option was to have a quasi-pyramidal marble fountain sculpted with panels of shallow steps so that water could flow through a shell at the top then tumble down the short flights of steps into a catchment basin below.

Elaborate fountain houses, or nymphaea, were built in a prominent position in gardens.54 These were imagined as being the home of a nymph and were meant to invoke a cave setting where nymphs abide, so accordingly a pumice panel was often inset into their design if possible. The shrine-like aedicula nymphaeum were usually sited against a garden wall; they had either a pediment or rounded roof, and a statue recess. Several were painted, but a number were encrusted with beautifully decorated mosaic and shell work. Shells were strongly suggestive of water domains and here they fulfilled a double connection: to the nymph who was seen as the source of the water, and with Venus who was born from the sea and also happens to be the prime goddess of gardens. These highly decorative architectural garden features were not just confined to Pompeii, for similar ones, although less well preserved have been discovered at Hadrian’s villa and on the Palatine.55 Some Romans decided to construct larger nymphaea that comprised several niches so that they resembled the facade of a Roman theatre, as in the House of the Bull at Pompeii56 and the House of Cupid and Psyche at Ostia. If you had a large villa you might want to erect a building with an interior that was meant to resemble a grotto. Water was brought to feed fountains inside, and this type of nymphaeum made suitably cool settings for feasting. The frescoed walls of the Auditorium of Maecenas in Rome is a good example with garden scenes painted in niches inside, this was of almost basilica-like proportions.

FIGURE 101. A freestanding water-stair fountain would enliven a small garden court or lightwell. Water slowly trickled through the holes in the shells and masks down the stairs and into a shallow catchment basin below, Aquileia Museum.

FIGURE 102. Mosaic and shell covered shrine to a water nymph, a nymphaeum, House of the Great Fountain, Pompeii.

FIGURE 103. A garden by the sea shore had a nearby sea cave that was converted into a luxury dining area for the Emperor Tiberius; scene of a dramatic event in AD 26 mentioned by Suetonius. Sperlonga, ancient Sperluncae (meaning the cave).

Those who were fortunate to have a cave on their estate could enhance it as seen in a fresco from Boscoreale (now in New York). Some Romans even converted a cave for dining parties, as mentioned by Seneca (see below). At Sperlonga (ancient Speluncae near Tarracina, Italy) the garden ran right up to the sea and a natural sea cave on the shoreline was converted into a superb grotto visited by Emperor Tiberius, it is a historical site described by Tacitus.57 The dining area was sited on a little island and sea water had been funnelled around it to make a large pool (which had several fish refuges set into its sides). The diners faced into the cave itself, and would have gazed upon a mythical pageant in over life-size sculptural form portraying Odysseus and his men blinding the giant Polyphemus, this made a fantastic backdrop. Fragments of this, and other sculptural groups, were discovered in the water where they had toppled or been thrown down at the end of antiquity. On the other side of the cave a chamber had been converted into a room where guests could sleep off their excesses. Pliny the Younger mentions such a garden room in his large garden.58

Novelty devices such as automata became fashionable among the wealthy and Hero of Alexandria’s book Pneumatics gives several detailed designs for their use in a garden. These ingenious devices were partly made of bronze and worked by means of running water, vacuum, levers and siphons. Some featured birds singing and moving and the bronze birds sitting on branches found at the luxurious House of Fabius Rufus at Pompeii are believed to have been part of one of these ancient devices.59

Descriptions of Roman gardens

Most contemporary Latin descriptions of actual gardens are short passages, but they give titbits of garden art in this period. Most quotations concern large properties which were of more interest to writers at that time. Cicero shows what would be ideal in a garden when he describes one in a letter to his brother who had been searching for a new villa:

I proceeded straight to your Fufidian estate, which we purchased for you in the last few weeks from Fufidius for 100,000 sesterces … A more shady spot in summer I never saw, water gushing out in lots of places … you will have a marvellous charming villa to live in, with the addition of a fishpond with jets d’eau, an exercising-ground, and a plantation of vines ready staked …60

Varro mentions that he had a stream running though his estate with bridges to cross over to an island, nearby there was a museum (this was similar to a nymphaeum) and further down there was an ornamental aviary which he describes in great detail.61 It included dining facilities so you could watch birds perched in tiers as if seated in a theatre. There were even two fish pools nearby with ducks swimming about. Seneca gives a partial indication of what he thought were luxurious additions in the garden at Vatia’s villa which was by the sea near Baiae, in what was a desirable sea-side location:

I could not describe the villa accurately; for I am familiar only with the front of the house, and with the parts which are in public view and can be seen by the mere passer-by. There are two grottoes, which cost a great deal of labour, as big as the most spacious hall, made by hand. One of these does not admit the rays of the sun, while the other keeps them until the sun sets [these would have been used as dining rooms, the former in the summer and the latter for winter months]. There is also a stream running through a grove of plane-trees, which draws for its supply both on the sea and on Lake Acheron; it intersects the grove just like a euripus, and is large enough to support fish.62

The euripus mentioned here was a fashionable water feature; one can be seen in the House of Loreius Tiburtinus at Pompeii. These were narrow elongated rectangular pools that sometimes have little bridges over them like the famous one built in the Campus Martius in Rome in 19 BC. These euripii alluded to the original Euripus, a celebrated narrow channel between mainland Greece and the island of Euboea that periodically had a tidal race. Romans liked to make such an association and large sheets of water were regularly named after water channels of antiquity or famous rivers, such as the Nile or the Canopus canal.63 The latter was in a notoriously liberal area near Alexandria in the Nile delta.

The Historiae Augusta reveals that the emperor Hadrian named different parts of his fabulous villa and gardens at Tivoli after some of his favourite places in the Empire that he had seen on his travels, and one of these was Canopus. His version of Canopus was a fabulous dining area placed at the edge of a vast sheet of water which was lined by an elegant colonnade and statues. A crocodile, in statuary form, furthered the tenuous connection with the Nile delta, and two river god fountain statues completed the scene. A narrow plant bed with a row of amphorae type plant pots was found on one side of this large pool. Hadrian also named an area after the Poikile a painted colonnade in Athens which he recreated as a magnificent long covered walkway overlooking a large garden. Here he could walk in his colonnade ‘in circuitum’; other wealthy Romans followed fashion and we find inscriptions about garden colonnades in a similar situation stating that a number of turns of the circuit could make a stade (625 Roman feet).64 Another area was landscaped to reflect the Vale of Tempe, a particularly beautiful spot in Thessaly. A cave was enhanced to suggest Hades, and there was an area to evoke the Academy of Athens. Hadrian was not alone in naming areas within gardens; Cicero called one part of his garden ‘the Academy’. When searching for statues to ornament this particular garden he requested muses, herms and philosophers, but not bacchantes (wanton female attendants of Bacchus) which would have spoilt the atmosphere he hoped to gain. Themed and period gardens are not new; Caligula had Egyptian statues brought from Egypt, and had copies of pharaohs made with his own features added so that he could adorn an ‘Egyptian’ pavilion and create a little Egypt for himself in the Horti Sallustiani at Rome.

We are very fortunate that Pliny’s nephew, known as Pliny the Younger, left two lengthy descriptions in letters inviting a friend to visit him and see the beauties of his villa and extensive gardens. He had a maritime villa at Laurentum, near Ostia, and a villa at Tifurnum. He relates how at the former, which was on the seashore, two prospect towers provided a view of the sea, his gardens, the woods and mountains. Statius and others also mentions how a fine view was much appreciated,65 and carefully landscaped gardens could enhance this. One part of Pliny’s garden at Laurentum had a circular drive (a gestatio) that was really a wide pathway or alley where people could go for litter-borne walks:

All around the drive runs a hedge of box, or rosemary to fill gaps, for box will flourish extensively where it is sheltered by the buildings, but dries up if exposed in the open to the wind and salt spray even at a distance. Inside the inner ring of the drive is a young and shady vine pergola … The garden itself is thickly planted with mulberries and figs.66

There was also ‘a terrace scented with violets’ at Laurentum, and a well stocked rustic kitchen garden. Pliny gives a fuller picture in words when speaking about his Tuscan villa. It was built on a sloping hillside so the gardens were designed on a series of terraces, he also included a gestatio which he likens to a Roman circus race-track:

In front of the colonnade is a terrace laid out with box hedges clipped into different shapes, from which a bank slopes down, also with figures of animals cut out of box facing each other on either side. On the level below there is a bed of acanthus so soft one could say it looks like water. All around is a path hedged by bushes which are trained and cut into different shapes, and then a drive [gestatio], oval like a racecourse, inside which are various box figures and clipped dwarf shrubs. The whole garden is enclosed by a dry-stone wall which is hidden from sight by a box hedge planted in tiers; outside is a meadow, as well worth seeing for its natural beauty as the formal garden I have described; then fields and more meadows and woods …67

Another section of these extensive gardens concerns his so-called hippodromus. This was an interesting garden form that is also found at Hadrian’s villa and in the imperial palace on the Palatine in Rome. The design of a hippodromus (sometimes called a stadium) again mimicked a race track and accordingly was made to resemble the long rectangular shape with a curved end to mark the turning point of the track. However, instead of staging horse races in these places there were promenades. Sidonius described an alternative option to have a large lake on his property (in Gaul) that could be turned into a boat racing venue. The island in the middle of this lake was fitted with turning posts and was the scene ‘of jolly wrecks of vessels which collide at the sports.’68 The huge pool found at Welschbillig (mentioned above) provides an actual example, but this particular pool had a long thin island in the centre just like a spina, the central reservation, seen in chariot racing tracks. Therefore the Welschbillig pool may have provided many happy hours of fun for staged boat races. Romans loved to make such allusions, boat races or promenades instead of race tracks. Pliny was rightly proud of this part of his garden because he careful details all its many parts. These insights into the highly developed art of Roman gardening are extremely valuable, and helps to visualise such a setting. The text is so vivid you can actually feel you are taking a stroll around the garden with him. He says that:

The design and beauty of the buildings are greatly surpassed by the riding-ground [hippodromus]. The centre is quite open so that the whole extent of the course can be seen as one enters. It is planted round with ivy-clad plane trees, green with their own leaves above, and below with the ivy which climbs over trunk and branch and links tree to tree as it spreads across them. Box shrubs grow between the plane trees, and outside there is a ring of laurel bushes which add their shade to that of the planes. Here the straight part of the course ends, curves round in a semicircle, and changes its appearance, becoming darker and more densely shaded by the cypress trees planted round to shelter it, whereas the inner circuits-for there are several-are in open sunshine; roses grow there and the cool shadow alternates with the pleasant warmth of the sun. At the end of the winding alleys of the rounded end of the course you return to the straight path, or rather paths, for there are several separated by intervening box hedges. Between the grass lawns here and there are box shrubs clipped into innumerable shapes, some being letters which spell the gardener’s name or his master’s; small obelisks of box alternate with fruit trees, and then suddenly in the midst of this ornamental scene is what looks like a piece of rural country planted there. The open space in the middle is set off by low plane trees planted on each side; farther off are acanthuses with their flexible glossy leaves, then more box figures and names.

At the upper end of the course is a curved dining seat of white marble, shaded by a vine trained over four slender pillars of Carystian marble. Water gushes out through pipes from under the seat as if pressed out by the weight of people sitting there, is caught in a stone cistern and then held in a finely-worked marble basin which is regulated by a hidden device so as to remain full without overflowing. The preliminaries and main dishes for dinner are placed on the edge of the basin, while the lighter ones float about in vessels shaped like birds or little boats. A fountain opposite plays and catches its water, throwing it high in the air so that it falls back into the basin, where it is played again at once through a jet connected with the inlet. Facing the seat is a bedroom … Here too a fountain rises and disappears underground, while here and there are marble chairs which anyone tired with walking appreciates as much as the building itself. By every chair is a tiny fountain, and throughout the riding-ground can be heard the sound of the streams directed into it, the flow of which can be controlled by hand to water one part of the garden or another or sometimes the whole at once.69

Pliny’s text serves to invoke the true spirit of a Roman garden. His clear descriptions and those of other authors allow a great understanding of the Roman way of life; it is also interesting that Romans viewed a garden as a subject worthy of discussion. Contemporary sources and archaeology combined allow us to appreciate the advances made in the art of garden landscaping during the Roman period.

Roman gardeners and topiary

There is no all embracing term for a gardener in the Roman period, for horticultural workers were named after the task they performed. Therefore there was a vinitor who trimmed vines, both in a vineyard and on garden pergolas covered by vines. An arborator (arbor means tree) was needed to trim and graft fruit trees and generally took care of large trees, lopping branches when needed. Someone who tended vegetables was called an olitor or holitor (both spellings exist) the word came from the Latin holeris which means vegetables. An aquarius was a water carrier, and he would be needed to water seedlings in nursery beds, and plants elsewhere in the garden. There was also a hortulanus who was someone involved in market gardening. The names of some of these ‘gardeners’ are preserved on a series of funerary inscriptions.70

There was however a specialist gardener a topiarius (pl. topiarii); their skilful work clipping hedges and bushes was referred to as opus topiarii and this led to our word topiary. The art of topiary was in fact invented by the Romans, Pliny the Elder credits Gaius Matius as the inventor during the reign of Augustus (27 BC–AD 14).71 The topiarius created topiar which means landscape, so he was also a landscape gardener and was known to design gardens. Both Pliny the Elder and Cicero show that topiarii were admired for their creativity. They were often highly skilled and there are several references to how box hedges could be trimmed into tiers, even obelisks, figures of ‘various shapes’, or they could spell out names in the well clipped hedges. Pliny the Elder mentioned that hedges were even made into representations of ‘hunting scenes or fleets of ships and imitations of real objects,’ such was the inventiveness of topiarii.

FIGURE 104. Detail of an arboritor grafting trees in a mosaic depicting rural tasks of the calendar year, from Vienne, now in St Germaine-en-Laye, near Paris.

FIGURE 105. Sinuous architecturally inspired lines of the topiary hedge bordering a wide path at Fishbourne Roman Palace, southern Britain.

Through archaeology we have evidence of the layout of hedges and some of the designs were quite intricate, such as those discovered bordering a wide path at the Palace at Fishbourne (Britain) dated AD 75. At Fishbourne the soil was poor and stony so the Romans dug deep bedding trenches and filled the trenches with good enriched dark soil so that the hedges would stand a better chance of survival. The contrasting colour and texture of the soil was immediately noticed by the excavators and revealed that the bedding trenches were in a classic architecturally inspired pattern: the straight lines were enlivened by alternating semicircular and rectangular recesses. The topiary hedge has been replanted at Fishbourne using box as archaeologists found remains of box nearby. Box was generally used when making a topiary hedge, we also hear of cypress and rosemary, but yew was never used in the garden at all because it was considered very poisonous.

Roman gardeners used tools such as a hoe (sarculum), pruning hook (falx arboraria), rake (rastrum), fork (ferrea). A spade (pala) was usually made of wood but had an iron shoe as a cutting blade, this type was called a palas lignea. A bidens was a form of hoe with two teeth. There was also a special twin headed tool called an ascia-rastrum this incorporated a bidens on one side and a sarculum on the other. All of these tools have been discovered on archaeological sites and some even appear in frescoes and mosaic. The tool most frequently shown in use by a horticulturalist is the bidens, they often feature in mosaics depicting tasks associated with the seasons of the year.

Plants were nurtured and transported in distinctive terracotta pots (ollae perforatae) which had at least three holes on the side as well as on the bottom. Two of these flower pots were found in the garden at Fishbourne. In Rome as one might expect a great number of flower pots have been unearthed, for instance in the small garden at the Villa of Livia at Primaporta 19 ollae perforatae had been placed around the edge of the small peristyle garden and a further three in the middle.72 In 1875 74 were discovered in other horti on the Esquiline, and so many were found at Nero’s Golden House that they gave up counting! As already mentioned, on occasion reused amphorae cut in half were an alternative form of plant pot, and in the Severan garden phase of the Vigna Barberini on the Palatine a variety of forms were used, some originally from Africa.73

Cato and Pliny mention that gardeners used ollae perforatae to propagate fruit trees and other plants by air layering.74 Baskets were sometimes used instead of a pot when layering a plant on the ground. Numerous sources mention how gardeners also made cuttings of perennial plants and herbs as well as bushes (from violets to southernwood). They grafted trees to improve fruiting and they also experimented to produce different flavoured fruit, e.g. by grafting plums onto apples and peaches on plums. We even hear of two or more fruit branches grafted onto one tree. Pliny the Elder also reveals that produce could be forced into early growth to bring forward the flowering of rose bushes or fruiting of fruit trees, to achieve this hot water was poured into a trench around the bush/tree.75 Martial hints that wealthy individuals may have had a form of conservatory where transparent stone was used to protect precious fruit trees from frost.76 Columella records the use of a specularium, miniature greenhouses made of transparent stone, which was wheeled around to take advantage of the sun’s heat so that early cucumbers could be grown for Emperor Tiberius; Seneca mentions that they were also used to force early blooms of lilies.77