Conclusions

Throughout the periods examined it has been possible to identify elements that could reasonably be described as a garden. These could be said to be different to the general practise of agriculture where the sole motive is the maximum production of food. There was a desire to produce something which in modern terms could be described as an amenity, which would give pleasure to the people who used it. This amenity/garden took many forms, from extensive parkland to the enclosed space within a dwelling or even the informal planting of small patches of ground with decorative plants.

One source of information comes from the field of archaeology. Archaeologists have long given up the simple search for art treasures, and in recent years have been prepared to examine areas that would once have been left blank because they contained no visible structures. Today archaeologists can use geophysical surveys to reveal evidence for garden areas and find evidence for cultivation. New scientific techniques such as pollen and soil analysis make it possible to give accurate identification of plant genera and species. Although the plant may not have grown exactly where the pollen was found we can be sure that it was grown nearby. For large gardens aerial photography can identify changes in ground levels that can mark out boundaries and sunken garden features (such as former fish pools). The new science of LIDAR, that uses laser imaging to identify ground contours over large areas to a surprisingly detailed scale, may well give us a great deal of new data in future years. A new area of research has been to examine anew ancient pottery. For instance, until recently we valued Minoan pottery for the information that we could deduce from their use of flower and plant motifs painted on their ceramic vessels, but now we can analyse traces left behind on the pot’s inner surface to identify the original contents and vegative remains. Science is not static and we can hope for unexpected new techniques in the future.

Surviving ancient literature (where it exists) is the ideal source for factual information on ancient gardens. The most prolific sources are probably from the Roman and medieval periods. The art of gardening was recognised as a worthy pursuit, and various Romans mention how their gardens gave them inspiration for either poetry or prose (Ovid and Pliny the Younger).1 Even an emperor was known to enjoy his gardens, such as Hadrian at Tivoli, and Emperor Diocletian once declared that he enjoyed his retirement growing vegetables!2 However, this may just have been a facetious way of saying he would have no further involvement in state affairs. The Roman writers in particular, on occasion, described their gardens or those of a friend and the details are enlightening for aspects of garden art. The agricultural manuals deal mainly with farming practice but indirectly illuminate some aspects of horticulture and gardening techniques. It is noticeable that Romans of high social standing wrote on these matters, in the same way that some 18th-century English aristocrats had a similar interest in land improvement. Byzantine, Islamic and medieval writers continued to produce agricultural manuals that incorporated elements of horticulture. Numerous Classical texts were re-discovered and examined in the late medieval and early Renaissance era and these gave inspiration for many Classical inspired gardens of the Renaissance and later periods.

FIGURE 155. Garden fresco, House of the Marine Venus, Pompeii.

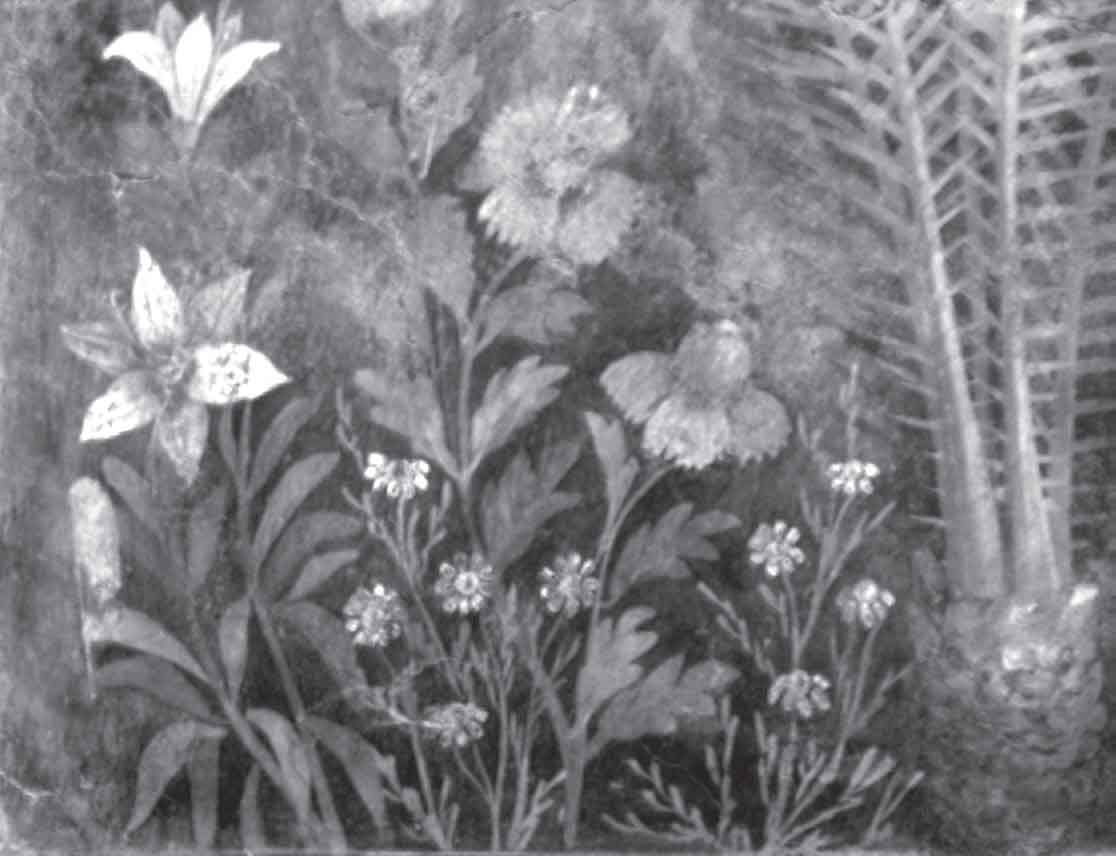

FIGURE 156. Fresco detail with garden plants, House of the Golden Bracelet, Pompeii.

Many earlier cultures compiled a herbal, for medicinal use and to enable practitioners to identify plants correctly before use. Medicinal texts have been found belonging to the Egyptians and Assyrians. There are even hints from references to medicinal plants in the Linear B tablets that indicates that the peoples of the Greek Bronze Age may have had knowledge that was passed down, but sadly not in a form that has survived. In the Islamic world there was a continuing interest in the work of Dioscorides, and the Greek tradition of Herbal Books. In Spain several noted Islamic gardeners wrote books on botany and a herbal. Medieval writers also provided plant lists and herbals, all of these were useful for identifying plants current to each period.

Religion played an important role in people’s lives in the past, and many cultures had a deity, or several, that had a responsibility for ensuring the fertility of plants as well as of animals and humans. There was a need for people to approach a god that could be petitioned to act on their behalf. Myths were woven about the lives and roles of the various gods and goddesses, and perhaps the best known are those of the Greeks and Romans, but we find that later a number of Christian saints appear to partly take over this role. The saints become someone who might intercede for you to God, and this helps to satisfy a basic age-old need, whether it was for help to combat a plague of insects or for an increase in the productivity of fruit and vegetables.

Many cultures had myths about the interactions between deities and plants, and again the Greeks more than others excelled at this. But we also find that other cultures wove a myth, or poem, based on the merits of certain trees/plants. The first one concerned the palm and the tamarisk of Mesopotamia that vied with each other, then there as the laurel and the olive of Greek literature, and later the oak and the holly played their part in the medieval period.

Some elements of gardening have passed down through the ages, partly because similar problems produce similar solutions. For instance, many garden tools have changed little because their basic design still works. Similarly, a water feature was a regular and favoured component of a garden wherever water was available in sufficient quantity. Provision of water varied from an aqueduct to supply the king’s private garden in Assyria, to a Roman town house with a small fountain pool where the aqueduct supplied the whole town and was chargeable. In the latter the water supply might let the fountain operate only part of the time, but this would still make a special notable feature in the garden.

Gardens evolve over time, and in some cases the countries concerned absorbed influence from outside, whether from diplomatic means or as a result of military expeditions abroad. For instance the finding and transplanting of newly discovered garden worthy plants. Another facet of cross cultural influences can be detected in the Greek translation of the Achaemenid Persian term for an enclosed garden, which then became a paradeisos, this was in turn translated into Latin and was the basis of our word paradise. The meaning had fundamentally changed so that the old hunting parks then became a peaceful kingdom in which the lion and lamb could lie down together. Some cultures did liken gardens to a paradise, a form of heaven on earth (Early Christian, Byzantine, Islamic and medieval). Eden was another Biblical theme used for comparative purposes. In a similar way the Greeks, Romans and Byzantines referred to the ever-fruitful Classical Homeric Gardens of Alkinoös, often claiming that theirs were better. Elements of continuity can be found in the groves of Greece translated into named themed garden areas on large country estates in Italy (e.g. Cicero’s ‘Academy’). Further examples of continuity are the peristyles of Rome that influenced the form of monastic cloister gardens. It also appears that Roman and Byzantine gardens influenced Islamic gardens and they in turn influenced garden designs of the Mughal court. Travellers to and from the Timurid Persian court may have brought ideas from distant lands (such as China and India) to the west, and contributed to the early introduction of more unusual/exotic plant species, but Chinese and Indian gardens are out of the scope of this current book.

One of the most famous gardens of antiquity is the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven great Wonders of the Ancient World. No-one has copied the model that was set so long ago, or none to our knowledge have survived. But, their place alongside the Pyramids and the Colossus of Rhodes, perhaps reinforced the idea that a garden could be a ‘wonder’. It promoted the idea that a garden was a proper interest for royalty and powerful individuals, and gardens came to be seen as a status symbol. To many the possession of a garden was another status indicator, and owners could vie with their neighbours on the expanse and expense in creating such a marvel, whether this was in Assyria, Babylon, Persia, Rome or in medieval Britain. Gardens whatever their size are an expression of their owners, then as now, and there is always a tendency to personalise the space, therefore few are slavish copies.

Gardeners are shown at work in the stone reliefs and frescoes of Egypt, the mosaics of Rome, the manuscripts of Persia and in medieval art. Whether the gardeners are depicted watering the garden laboriously using water-pots on a shoulder-yoke or a shaduf (as in Egypt and Mesopotamia), planting out, pruning or digging, their toil is recorded. The fact that their humble work was also commented on, and that their occupation was specified apart from being just labourers shows a recognition of their particular work. In the Roman period there were even specific titles for each specialism in the garden (arboritor, olitor, topiarius). Several Roman tombstones recorded the personal names of individual gardeners, such as Lucrio and Florus topiarii working in Campania.3 The skills of topiarii, especially their topiary work, was much admired and commented upon. Individuals in the various societies became head gardeners, and some were noted for their creative designs, such as Mirak-I-Sayyid Ghiyas the Persian from Herat. However, many garden designers remain anonymous for their work is often attributed to their ruler or the owner of the garden. This book has tried to shed light on the gardeners’ hard work to let their achievements shine through and live on.

One of the benefits to present society is the early introduction and dissemination of plants, and this commenced from the Egyptian period onwards. As mentioned there were times when the ruler, or his general, led expeditions to foreign lands with the intention to seize or quell cities and expand territory. One of the indirect consequences of this was that different trees and plants were noted en route and examples were ‘captured’ and transported back to the victors homeland. Not all specimens would have survived, but of those that did some notable plant species became established on new soils. The vine and pomegranate are among the early plants introduced to Egypt, and later the ‘Botanical Garden’ room at Karnak depicted plant trophies on its walls. We hear that fruit trees were transported from Anatolia to Mesopotamia by the Assyrians. The Roman general Lucullus returned from Pontus (on the Black Sea coast of Turkey) with the sweet cherry which was previously unknown to Rome. Roman individuals actively sought new or better plant species, of fruit trees, and even of roses to extend their flowering season. Garden worthy specimens were acclimatised and then introduced to places throughout the Roman Empire. Islamic rulers introduced numerous plants to gardens in southern Spain, one of these being the orange. When dialogue commenced between Islamic Spain and its Christian neighbours an exchange of ideas were possible and there are instances when horticultural practises, and new plant species were brought into the medieval world. Several further plant introductions were made during the medieval period, such as the hollyhock. This was called Holyoc or the Rose of Spain, which perhaps indicates the region where it was previously known (Pays d’Oc or northern Spain) for it is believed to have been introduced by Queen Eleanor of Castile in 1255.4 The process of plant introductions continues even today.

The plant lists that accompany each chapter of this book will aid the identification of plants known during any particular epoch. The lists might also help people when contemplating making a period garden of their own, or for their community. Several reconstructions of gardens have been made for the public and these enable the viewer to visualise the setting in person.

Reconstructions of period gardens

Egyptian

There is a small Egyptian area at Biddulph Grange, near Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, but this is really a showcase of Egyptian architecture with an Egyptian style doorway flanked by a pair of sphinx and tiered hedges, there are no pools or flowers in this area. There are ancient Egyptian plants in the Botanic Gardens in Cairo, and on the Botanical Island near Aswan.

Mesopotamia and the Near East

Three Bible Gardens have been created at Elgin and Golspie in Scotland, and Garstang in Lancashire. All three contain plants mentioned in the Bible within a modern setting.

Greek

The Greek garden temple at Clumber Park, Nottinghamshire, and the Classical inspired temple at Stourhead Gardens, Wiltshire, are situated in landscape settings that evoke the groves of Greece. In the Agora excavations area at Athens the grove of trees around the Temple of Hephaestus have been replanted in the original ancient Greek plant pits. In the Diomedes Botanic Garden in Athens (to the left of the main gate) there is an area devoted to Greek plants mentioned by Theophrastus and other ancient Greek writers.

Roman

Apart from Pompeii in Italy, there are several Roman-style gardens in the UK and elsewhere in the former provinces of Roman Empire.5 At Fishbourne Roman Palace, near Chichester, in West Sussex, the large garden with architecturally inspired topiary has been recreated from archaeological evidence found on site. There is a small museum dedicated to Roman gardening, and nearby there are several display beds with plants of the period.

Part of the Roman Museum at Caerleon in Wales has a Roman-style garden with period plants and an al fresco dining area. At South Shields, on Hadrian’s Wall, there is a Roman-style garden with herbs and box hedges.

Chester Zoo’s Millennium project saw the creation of a Roman-style garden area containing a decorative garden with ornamental pools, statuary, pergolas and period ornamental plants, plus a section with herbs and vegetables.

The Prince of Wales garden at Highgrove, Gloucestershire, contains an Islamic-style garden based on a design from a Persian carpet. This garden was created for the Chelsea Flower Show and subsequently was re-laid at Highgrove.

The Islamic gardens of Granada, and especially the Patio Acequia, have provided the inspiration for the Alhambra Speciality Garden created in Roundhay Park in Leeds. It contains areas with an elongated pool, fountains, pavilion, and some period plants in a formal setting with elegant cypress trees and hedges.

Medieval

A medieval style garden was designed by Sylvia Landsberg to reflect the three herbers that were created for Henry III and his Queen Eleanor in the castle at Winchester c.1235. The recreated garden was made next to the Great Hall. The royal herber was provided with a tunnel pergola, a hortus conclusus with a turf seat and an elegant fountain.

A garden was made at Tretower Court in Powys, Wales, designed by Elizabeth Whittle for Cadw. In the 15th century this was the home of Sir Roger Vaughan. The garden is split into two halves. One section is enclosed by latticework fences and contains a gothic fountain as a centrepiece, this is surrounded by borders of lavender and other herbs. A pergola covered with white Burnet roses runs along two sides of this garden. The second half is a hortus conclusus, or Mary Garden, with an arched entrance facing a turf seat. The whole is ringed by a hedge of red Rosa gallica and Rosa mundi roses. The scent from the roses all around you as you sit there is wonderful.

FIGURE 157. Recreated medieval garden at Tretower Court, Wales.

At Prebendal Manor House, near Peterborough the recreated medieval gardens extends to 5 acres (c.2 ha). It was designed by Michael Brown. He aimed to give an idea of what you might expect to find in a garden of a wealthy establishment of the late 14th century. There is a medieval dovecote on site and, next to the old tithe barn, a gardener’s hut with replica tools such as a wooden spade with an iron shoe, and watering pots (a thumb watering pot, see Fig. 142). One section of the garden recreates the raised plant beds seen in physic gardens, a second area is enclosed by a lattice fence making a hortus conclusus, full of herbs and with a central fountain. A third part is laid out as a flowery mead with a rose pergola to one side, and a fourth features a secluded bower with turf seats. There are fishponds, orchards and beds that demonstrate medieval methods of growing vegetables and other plants of the period. Of the period plants grown at Prebendal there are exotic ones such as mandrake and a dragon plant (Dracunculus vulgaris) a member of the Arum family.

Notes

1. Ovid Trista, I, 11, 37. trans. A. L. Wheeler, London, 1986; Pliny, Epistles IX, 36, 3. trans. B. Radice, London, 1969.

2. Epitome de Caesaribus, 39, 5–6. www.thelatinlibrary.com/victor.caes2.html

3. CIL.X.1, 1744; CIL 9945; c.f. Farrar 1998, 161.

4. Harvey, 1981, 127–130.

5. See Farrar 1998, 200–203; more are included in the Farrar 2011 edition, History Press.