Chapter 8. Wild Dogs and Dogging

The hide of a dingo of immense size . . . was taken into Braidwood last week. [A] bullet penetrated the mouth, . . . the pain of which so enraged the animal that he made straight for his enemy. The man’s mate (both were rabbiters) came to his aid and they clubbed the dingo with their rifles.

‘An Old-Man Dingo.’ NSW Shoalhaven News and South Coast Districts Advertiser, 25 June 1910, p.5.

Doggers, the shooters, poisoners and trappers of wild dogs, make few distinctions between the native dog, the dingo (Canis lupus dingo), feral dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) and the expanding interbred varieties found in the bush. While the fossil record for the dingo is modest, it suggests that the creature, considered the continent’s first feral animal, is a species descended from an Indian plains wolf.1 Feral dogs and dingoes kill for sport, particularly when they form packs. The Queensland professional dogger, Ned Wilson, a hunter with 33 years experience states that ‘if there are 5 or 6 [dogs] together, I would say there would be no limit on what they may do. The amount of senseless killing they could do would depend almost entirely on the number of animals . . . on hand.’ It is Wilson’s view that ‘If nothing is done to reduce their numbers, there would be so many dingoes that [sheep] farming as we know it would be impossible.’2

Other experienced bushmen have validated Wilson’s observation, stressing that dingoes were vicious predators in sheep country where it is claimed, ‘a dingo bitch could teach her pups to kill hundreds in a night’. A study for the West Australian Agriculture Protection Board found that of the 166 sheep attacked and killed by dingoes on a Pilbara sheep station, 40 percent of the casualties were killed for sport and not eaten.3 In southwest Queensland, one historian reports that during the late 1930s, local graziers were overwhelmed by the dingo population and abandoned sheep-farming entirely.4

Alternatively, it has been observed that feral cats, rabbits, goats or wild pigs were notably suppressed or absent in areas with a high dingo population.5 Purcell’s study of the dingo cites West Australian diet studies suggesting the dingoes consume each other at a similar ratio to their consumption of domestic sheep.6 Mature cattle, on the other hand, seem less affected by the dingo population while calves as well as mature livestock in poor condition are at risk, particularly during mustering.7

Some authorities note that approximately 75 percent of dingoes encountered in Central Australia travelled as lone animals, rather than in a pack. Paradoxically, in true wilderness areas where human contact is rare, the dingo appears to prefer living in packs.8

According to the Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre, the most effective dog control in Australia is ‘The Dog Fence’, a 5600-kilometre fence reaching from the Great Australian Bight in South Australia to southwest Queensland. But, trapping, poisoning and shooting remained the favoured methods for eliminating wild dogs until the 21st century.9 As recently as 2010, the Western Australia Department of Agriculture was allocating several million dollars per year to doggers to manage its wild dog population and protect the state’s small livestock such as goats and sheep.10

Dingo bitch and pup, 1964. National Archives of Australia, no.A1200, L47982.

While doggers continue to be retained on wages by rural shire councils and graziers, in the past they were often paid a bounty for dog scalps or occasionally, dog ear pairs that could be redeemed at government offices (usually police stations) in several states. Considerable money could be made in the profession. The late bushman and leather-worker R.M. Williams worked as a dogger in Central Australia in the 1920s and writes in his memoir that he ‘had noticed that all through the ranges where we had been were great numbers of dingoes. I told [my partner] that I intended to return and collect scalps which could be traded from the natives and were saleable to the government at police stations for seven shillings and sixpence each . . . (2014 equivalent $24). [So] . . . we headed out to the Musgraves again to make our fortune with the collection of dingo scalps.’11 Doggers also bought or traded scalps from the Aborigines and took them across the border into Western Australia, where a bounty was available.

“Overseer [Phil Schaffert] on a cattle property in northern Australia issues a receipt to Aboriginal stockmen for dingo pelts,” 1961. National Archives of Australia, no.A1200, L39260.

Williams and his friends also used the scalps as currency, selling them to other doggers (miners and prospectors) who were working in the area.12 Having little use for traditional money exchange, the Aborigines used the wild dog scalps and ears in a local barter economy.13 While integrating the wild dog bounty into their culture (and cuisine), Brad Purcell’s Dingo observes that indigenous Australians have also integrated the dingo in their art and adopted the animal in dreaming stories.14 This does not mean, however, that Aboriginal people were any less reticent in trapping or killing wild dogs.

A role for the Aborigines in the dogging industry had emerged several decades before the great Australian traveller, Ernestine Hill, described the Central Australian township of Oodnadatta, South Australia as the ‘dog capital of Australia’ in 1940.15 ‘With the blacks and like the blacks,’ she writes, ‘the doggers travel from soak to spring and from spring to waterhole. . . . Euro (wallaroo) meat, flour and tea [are] their only rations. Two or three times a year, the spoils are sent in to Hall’s Creek, the Katherine, Alice Springs or Oodnadatta . . . to be counted at the police station or store, [gaining] a credit balance against flour and trade tobacco. . . . Packed in bags of about 100 each, the scalps are freighted south on the Ghan for official checks and verification.’ ‘That Ernabella country was the best place, mate,’ reported dogger Walter Smith. ‘Talk about the dingos there! Caves there . . . and they go there mating time. All the dogs go there . . .’16

The doggers operating on the reserves found it more profitable to employ local Aboriginal people to obtain scalps for them. Their hunting skills and knowledge of dingo habits enabled them to obtain many more scalps than any white man could hope to shoot or trap on his own.

Tom Gara. ‘Doggers in the North West.’ (SA), www.researchgate.net/publication/268028332_DOGGERS_IN_THE_NORTH-WEST, 2005, p.1.

Some observers assert that amongst the early doggers in South Australia, ‘the great bulk [of the scalps were] obtained by trading with the blacks, whose minute knowledge of the habits of the dogs, and particularly of their seasonal movements and breeding places, enabled them to get results quite beyond the reach of the white man’.17 Tom Gara’s study of dogging in north-western South Australia found Aborigines, using their superior tracking skills, could easily follow a female dingo to her pups and recover scalps from the litter, then cook and eat the pups.18

Walter Smith, born in the late 19th century and working as a dogger in the Ernabella region in the early decades of the 20th century, also observed that the Aborigines would take up a position downwind of a den, imitate the call of the dingo female to attract the pups, who could then be speared, scalped and eaten. ‘That’s how we got the scalps too,’ Smith told an interviewer. ‘Give them [the Aborigines] a butcher knife or tommyhawk for a couple of scalps. Sometimes they’ll bring us 10 to 12 [scalps]. They just take that scalp for us and cook him then.’19

Before the European doggers appeared in the region and the bounty-attracting skin or scalp became a valuable trade item, dingoes were traditionally cooked in their hides and eaten with enthusiasm by the local Anangu people. While wild dogs remained a local favourite, skinning the animal before cooking became more commonplace after the dogger traders appeared. Anangu sources insisted that only wild dogs were eaten, never camp dogs.20

“Two tribesmen from a group of Pintubi people,” Northern territory, 1957. “Young dingoes were used for hunting purposes.” National Archives of Australia, no.A1200, L25172.

In 1940, ‘one man tallied 790 scalps, nearly £300 (2014 equivalent $23,800)’, Hill writes. ‘In the Kimberley and the Musgraves, the white man carries traps . . . The blacks prefer to follow their own primaeval methods, spearing the dingo at a waterhole or tracking him to his lair, watching to catch him asleep. It takes some doing. . . . While a white man will laboriously secure two or three in a week, the tribe comes in with 20 scalps slung across its shoulders . . .’21

The efficiency of Aboriginal hunters is also recorded by a number of other observers. Eric Rolls reports, ‘From 1953–1960, [the anthropologist M.J.] Meggitt worked amongst the Walbiri tribe on Mt Doreen Station and the Yuendumu mission northwest of Alice Springs. In July and August of each year, about a 100 native hunters went into the hills and returned with up to 700 [dingo] scalps.’22

Within the areas where they worked, some doggers were implicated in the commercial as well as the sexual exploitation of Aborigines. Tom Gara’s essay ‘Doggers in the North-West’ [South Australia] surveys the regional activities of Eurasian and Aboriginal doggers, noting the synergies that existed between the two communities. The dog shooters and trappers trespassed on the Aboriginal reserves as they pleased and trading abuses quickly emerged between the Aborigines and the European doggers in the Ernabella region. A dingo scalp was worth 7 shillings 6d (2014 equivalent $28) in South Australia in 1924 and a recent study verifies that a dogging expedition in the Musgrave Ranges of South Australia took axes and knives to barter for valuable bounty-attracting dingo scalps with the indigenous Anangu population.23

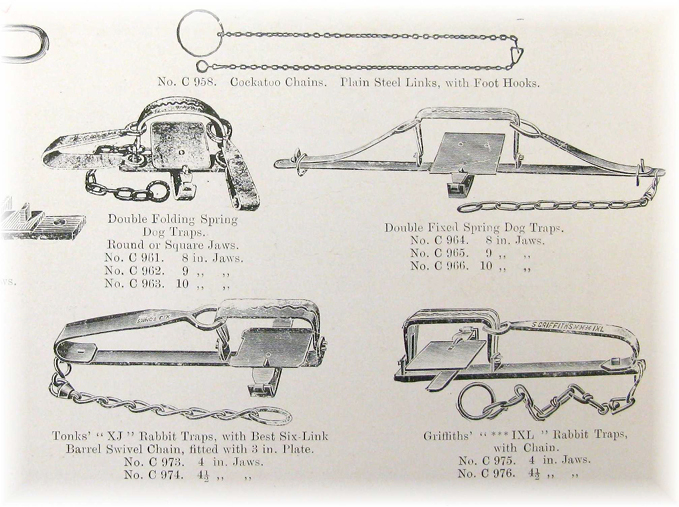

Dog and rabbit traps, detail, Feldheim, Gotthelf & Co. catalogue, Barrack Street, 1905. p.432.

R.M. Williams recorded the Ernabella administrator, ‘[Dr Duguid] . . . felt that the Aborigines should be given the full bounty on dingo scalps, to provide an effective discouragement to the growing army of adventurers trading handfuls of flour for the scalps.’24 In an effort to control this economic exploitation of Aboriginal people, the Presbyterian Minister of the Mission Station at Ernabella was ultimately appointed ‘official receiver’ of dingo scalps offering the generous sum of 7/6 (2014 equivalent $28) versus what Gara describes as a reward of a ‘handful of flour or an old shirt’ customary before the new bounty programme.25

Diana Young’s economic assessment of the dingo bounty trade concludes that once the nexus between commercial doggers and the Aborigines was severed by this direct payment of bounties, dogging kept the Anangu from travelling to settled areas, fostered their attachment to the Presbyterian mission and provided conventional material wealth. This bounty, in turn, encouraged the consumption of European commodities from the mission stores.26

The Western Australia Department of Agriculture says it is close to finalising the allocation of doggers to help control the increasing numbers of wild dogs. In April [2010], the State Government announced more than $5 million to employ eight additional doggers.

www.abc.net.au/news/2010-09-14/government-set-to-announce-dogger-allocations/2260068. 28 April 2014.

Bounty programmes have been used in many states to encourage the destruction of wild dogs. Tom Gara claims that by 1934, 500,000 dingo and wild dog scalps had been redeemed for bounties in South Australia, West Australia and the Northern Territory.27 Dingoes also attracted a £5 (2014 equivalent $370) bounty from the Chief Commissioner of the Federal Capital Territory (now ACT) in the late 1920s when dingo numbers soared in the Cotter River area. The costs associated with the bounty payments were shared by the Commissioner’s office and the stock-owners in the region.28 Not surprisingly, claims were made that the wild dog problems arose from a lack of control in the border regions of New South Wales.

A South Australian grazier explains some of the difficulties associated with the state-based bounty system. His explanation is rewarding. ‘When we obtained the Mulyungarie Lease, the [lease] manager Mr Andrew Smith, when he visited the run, took with him in his buggy a bottle of poisoned baits, which he dropped about as he drove from water to water. He found a professional [dog] scalper camped at one of the dams, and as the dogs were plentiful, he was making good wages . . . by trapping, and he had been there for a considerable time. Mr Smith returned about a fortnight later and found the scalper picking up his dog traps and belongings, And he remarked, “This was no place for him.” He had taken 60 or 70 scalps off the dogs Mr Smith’s baits had poisoned, and the latter asked what he was going to do with them, as they were of no value in South Australia.’

‘It appeared that [the dogger’s] employer had a station in New South Wales, and that station was a ratepayer of the Pastures Board and would get 10/ (2014 equivalent $47) per scalp from the board. The station allowed another 10/, so this scalper would get £60 or £70 (2014 equivalent $5,700-$6,600) for scalps he had only had the trouble of taking off the [poisoned] dogs. “Of course,” he remarked, “I will have to put the scalps in a few at a time, or the price might be reduced.”’29

Dingo and domestic dog cross-breed, 2009. Photograph by André Geißenhöner, Wikimedia Commons.

In the 21st century, wild dogs continue to threaten livestock in several states. Along the dingo fence, Queensland dingo scalp bounties were paid for over 14,000 wild dogs in the mid-1980s.30 In 2010, the Western Australia Department of Agriculture received $5 million to appoint doggers to control a rapidly increasing population of the animals.31 In the following year, the Victorian government reinstated a bounty on wild dogs and foxes setting aside $4 million for a four-year programme to control them. Wild dogs earned a $50 bounty while a fox brought $10. The bounty is redeemable by presenting the scalped face of the animal. Foxes proved vulnerable to shooters while wild dogs proved a more difficult quarry and newspaper reports recorded 10,000 fox pelts redeemed per month with a modest 300 wild dog kills over an eight-month period.32

In late 2014, NSW Primary Industries described a resurgent population of wild dogs as ‘a very significant problem’ and announced a $2.4 million dollar programme of baiting through a range of state-wide agencies. They planned to fund the distribution of over 240,000 wild dog baits through hand-distribution and aerial baiting in the thinly populated western districts.33

Dog Stiffeners

Professional doggers who worked with poisons were known colloquially as ‘Dog Stiffeners’. Although the cost of poison discouraged some doggers, poisoning dogs with strychnine was favoured amongst pastoralists before the introduction of the oral poison marketed as ‘1080’.34 Although spreading poison baits always meant there would be collateral damage to native animals (including birds), it was considered safer for livestock than inviting shooters onto their property. There was always a chance, of course, a child, working dog or family pet might consume a poison bait.35

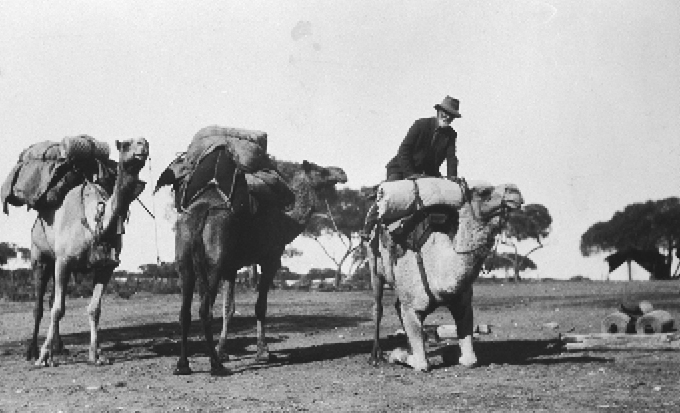

“The Dogger and his camels; he rode the dog fence of over 500 miles once a fortnight completing repairs and poisoning dingoes.” ca.1924. State Library of South Australia, no.B 53553-1.

The strychnine was supplied in a white powder, tablet or crystal form and the process for preparing and spreading baits was simple. A 1916 account explains that ‘[B]aits are made by cutting fresh meat [typically kangaroo or a steer] into 1½ oz (45 gram) pieces. In the centre of each piece a cut is made with a pocketknife, and the strychnine inserted. Then each piece of meat is rolled up separately in a piece of newspaper. In this manner 200 or 300 baits are prepared in one batch. When the poisoner is ready to go out, he fills his split bag with baits, slings it over the back of the saddle and off he rides.’

‘Arriving at the proper place, he takes out his “trail,” which is generally a piece of tainted meat tied to the end of a string, the other end of which is tied to his saddle. Others take an old waterbag, into which has been emptied a pot or more of anchovy paste, sprinkled over with oil of aniseed and oil of rhodium [rosewood oil]. Some trappers swear by this “trail” and assert that a dingo will sometimes follow it until he goes stone blind.’36

We’d get [the dogs trapped], [The Queensland Government dogger Mick would] shoot them there in the trap, drive up beside them in this old unregistered Land Rover and he’d shoot them out of the window, then he’d get out and scalp them. He always put a bit of strychnine on the back of the dog then. He’d generally get an eagle hawk . . .

Kerry Kendall interviewed by Bruce Simpson and Bill Gammage in the Drovers oral history, 2002, National Library of Australia. ORAL TRC 4599/35 transcript, p.21.

Ian Parkes worked as a jackeroo in the northwest of Western Australia and recalls in his 2012 memoir cutting kangaroo meat into 1-inch (25-millimetre) squares, inserting a strychnine tablet into each one and dropping the baits along the sheep pads (tracks) at intervals of 5 to 10 yards (4.5–9 metres). He threw out hundreds of baits over the course of several days. If he happened to shoot a kangaroo, he baited the animal’s carcass with strychnine crystals.37

In dry country, accessible water locations (springs, soaks, bores, billabongs) provided doggers with the ideal location for poisoning wild dogs. ‘You’d see a lot of tracks and you would think, “Oh, they’re coming in to water.” Well, you put the poisoned bait out about a mile (1.6 kilometres) from the water,’ the Central Australian dogger Walter Smith explains. . . . ‘The dingos are pretty thirsty but they eat that bait and come in; they get a drink of water and only go a couple of yards (1.6 metres) and they fall down . . .’38

But distributing strychnine around the countryside could have unanticipated results for humans as well as four-legged carnivores. In 1909, the famous Australian endurance cyclist Frances Birtles was riding from Fremantle to Sydney through Broken Hill, a distance of 3056 miles (4900 kilometres). The Perth Western Mail reported, ‘On the coast of South Australia, Birtles met with a rather startling experience. He arrived at a rock-hole, and filled his water-bag. He also took a drink from the hole. This [water], however, made him ill, and he discovered that the water had been poisoned. He is under the impression that some party with a camel team, or a wild-dog trapping expedition, had poisoned the water with the idea of killing the wild dogs and picking up the scalps on the return journey.’39

There have also been a number of references to the suspected poisoning of Aboriginal people by Europeans. Research for the 2012 exhibition on the West Australian Canning Stock Route held at Sydney’s Australian Museum presented anecdotal references about the poisoning of West Australian Aborigines by persons unknown. The West Australian artist Lily Long records that ‘[t]his [poisoning] used to happen to Aboriginal people on the Canning Stock Route too. My auntie’s husband was poisoned by white people. They used to leave bullock leg with poison for people to eat.’40 This tragic poisoning suggests baits spread by doggers were found and consumed by indigenous people.

Hawky Bob, [is] perhaps the best dog trapper in the west. His argument in [cyanide’s] favour is that it is deadlier than other poisons. The dog cannot go far after taking the bait; thus when the trapper goes to collect the kill before sun-up and crow-time, he has little trouble in finding the beast. Slow poisons allow the pests to get some distance away, which means that the crows might find them first, and thus rob you of the reward.

‘Virtues of Cyanide.’ Sydney Morning Herald. 17 January 1925, p.13.

Some wild dog trappers also use poison on their traps by applying poison on a rag tied around the trap jaws. When the trap is sprung, a desperate dog could chew through its leg to free itself. If the trap jaws are contaminated with poison, the moist tissues of the dog’s nose or mouth can easily take in enough poison to cause death. Anecdotally, this practice appears to have died out and its widespread use seems inexpedient and unlikely.

Trapping

Trapping wild dogs requires an intimate knowledge of dog behaviour as the trap must be free of any alienating scent; it must be laid where the animal is likely to step into it; this means that the gait and walking behaviour of a dog must be understood. In the past, attractants have also been applied to the trap area (or the trap) to draw dogs to the scene. Introduced scents may distract the animal from sensing the presence of a trap or a disturbed site.

The Queensland dogger Ned Wilson divides dogs into two groups, the ‘silly dog’ and the ‘educated dog’ categories. The silly dog is typically a young animal that walks confidently along game trails leading to water or hunting grounds.41 The ‘educated dog’ has some experience of doggers and pays close attention to the potential presence of humans. Wilson is emphatic that an ‘educated dog’ that has managed to escape a springing trap will be a difficult animal to eliminate.

A trap has a pair of spring-driven jaws held open by a steel plate. The traps are usually dug into hollows with the trapper’s tomahawk and a steel peg tethering a chain to the trap is driven in with the hammer end of the tomahawk. This prevents the animal from running away with the trap. Once the spring jaws are set, a paper or in some cases, a poison-infused cloth is laid over the plate, then the trap, chain and peg are covered with light soil, grass or other camouflage.

Without the use of a poisoned rag on the jaws of the trap, a trapped and frenzied wild dog would break or chew (or both) through its leg in an effort to escape the trap, and ultimately the trapper. Some doggers consider that not using strychnine on the trap is inhumane. Others consider it a nuisance. It was a much-debated topic amongst trappers, especially those who kept dogs of their own.

Some trappers use aniseed, or take some of the earth from the place where a tame dog sleeps. ‘Hawky Bob’ [the trapper] has a special mixture of his own, but he keeps it secret. Wild horses could not drag it from him. Certainly it is most effective in enticing dogs, and has the opposite effect on human beings.42

Edwin Waller. ‘Trapping Wild Dogs.’ Sydney Morning Herald, 17 January 1925, p.13.

One school of doggers considered strychnine application to traps was a mark of competence. ‘For many years I was a professional dingo trapper in the far west of New South Wales,’ ‘Arthur’ from Longreach, Queensland writes. ‘Professional dingo trappers always poisoned their trap each time. A strip of rag is bound around on the trap’s jaws and then a liberal dose of strychnine is applied to the rag. More wrap is then applied to imprison the strychnine. I personally bound the rag tightly with three ties of thin copper wire to stop it from coming undone. When the dingo or wild dog is trapped, it immediately attacks the trap. But before any . . . horrific injuries . . . can occur, the trapped dog fastens onto the trap with his jaws, in doing so, he breaks the rag holding the strychnine and inevitably the animal is dead within a few minutes.’43

To prevent the trapped dog from breaking its leg or chewing the leg free, some doggers abandoned the use of pegs to secure the trap. They ‘tethered the trap to some heavy instrument, such as a pick head or an axe head, so that the dog will not break its leg trying to get away [and escape, leaving its lower limb behind]. Instead it will drag the trap and weight away, but not far. And if it did happen that it was able to travel some distance, the trap and weight leave a trail that is easily followed.’44 ‘Arthur’ from Longreach also employed this method combined with poison. ‘[V]ery seldom is the animal more than 15 to 20 feet [4.5–6 metres] from where it was trapped,’ he says, ‘owing to the lethal does of strychnine.’

Shooters

In some areas, shooting dogs is seen as a sport rather than a vocation; trapping and poisoning is seen as more effective. Veteran trappers such as Ned Wilson combined both and carried a rifle while trapping on the chance of getting a shot. Sporting shooters summon dogs with baits and rabbit distress calls to draw them within range of their rifles. But ‘[t]he man who shoots a dog is lucky’, writes one contemporary. . . . ‘[S]hooting is a slow game, the dogs are too cunning; their sense of smell too acute. Gunpowder is just a danger sign.’45

The Menindee dogger Sprig Watson spent many years shooting dogs for a station in the Strzelecki Desert. As a talisman against the isolation, he kept a diary that he later shared with a Sydney journalist. ‘Monday. Had another good night, shot 12 overnight till 3 am, got too cold. Went to bed. While scalping my dogs this morning, I look up and see three dogs drinking together 70 yards (64 metres) away broadside on and tightly bunched. Can I get three with one shot? Bang. Two go down in a screaming heap . . .’46

I was talking to a kangaroo shooter the other day. He is reckoned to be one of the finest rifle shots in Queensland. I said to him, ‘How much do you charge for shooting dogs while you’re knocking around after kangaroos?’ He replied, ‘How much do you pay?’ ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘Never mind what I pay, it’s what the Board pays. The cows tax me for the destruction of dingoes!’ The shooter laughed and shrugged his shoulders. ‘I wouldn’t draw bead on a dog for the Board’s money,’ he said. After a while he added, ‘Anyhow, why spoil a good thing? These dogs are breeding fast. In a few years there’ll be money in them.’

‘Damned Dingo Boards.’ The Queensland Longreach Leader, 25 July 1924, p.17.

Doggers and their Character

Dogging carried the aura of an eccentric profession and their elusive quarry was poorly understood by the public. News items describe trappers wearing wild dog hide clothing to mask their human scent; others observed them mixing mysterious ‘scents’ and poisons that taxed the imagination. Some practised wild dog poisoning by hanging ‘small bags of poisons to trees with a carcass or bones beneath it to catch the drip. When the sun melts the fat, it drips out of the bag . . .’47 Their ready access to poison suggested potential harm to themselves and to others. And amongst doggers, firearms are commonplace, adding a note of menace and at times, this menace merged with their own practice.

A Croatian émigré, the late Ted Grabovack, worked a section of the South Australian dog fence until his death at the fence at 75 years of age in 2001. Grabovack, whose techniques are described in James Woodford’s The Dog Fence, shot, poisoned and trapped wild dogs and hung their carcasses on the fence as trophies. ‘Old Ted,’ said one of his compatriots, ‘put the “T” in Tough.’ He was effective but ‘a bit of a law unto himself and [for his employees], hard to handle’.48

As one observer noted, the hunters were ‘Doggers by occupation, Dogged by nature’.49 Tom Gara observed that doggers were usually bushmen ‘who had worked all their lives on the pastoral frontier; they were familiar with Aboriginal customs and many already had, or soon acquired Aboriginal wives who helped in establishing trading networks with the local people’.50

Following the Wiluna (West Australia) jury’s recommendation to mercy on the ground that the murdered man gave provocation, the sentence of death recorded against two Aborigines, Yalyalli and Maloora, for the willful murder of Joseph Edward Wilkins at Boonjinji Soak about August, 1936, was commuted to 10 years imprisonment today. The Aborigines said that Wilkins, a young English pastoralist, interfered with their women. While on a dog trapping expedition, Wilkins was speared [then] killed with a tomahawk . . .

‘Ten Years Gaol. Desert Murderers of Young Englishman.’ Cairns Post, 16 December 1937, p.6.

Conflict between doggers and Aborigines was a constant in the Central Australian frontier areas beyond Eurasian settlements; shootings, rape and other crimes were reported. The South Australian police were the closest law enforcement agency and they showed little enthusiasm for patrolling Aboriginal reserves. In 1928, the murder of the Lander River dogger Fred Brooks 250 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs (Coniston Station) set off a massacre of an estimated 31 Aborigines when the local police and graziers initiated a retaliatory raid. A murder trial found that the murder was provoked by the dogger’s involvement with an Aboriginal woman.51 The Aborigines charged with the Brooks murder were acquitted.

Dogging is, of necessity, a lonely occupation. To make the profession profitable, long hours and considerable walking are required. While the use of poison also has its own dangers, traps can accidently spring and where there are firearms, there is always the chance of an accidental discharge. The 1908 death of the Uralla, NSW dogger Harry Smith, ‘a well-known bushman and native dog trapper’ is recorded in the Sydney Morning Herald.

The Herald reported that Smith ‘walked in line of a fixed spring gun loaded with a heavy charge of buckshot, intended for a large dingo. His son-in-law, Albert Yates, called to him to be careful, but the warning was too late. Smith had touched the connecting wire, and he received the full charge in his stomach . . .’52