Chapter 1. Shooters, Trappers and Poisoners

It is old Peter, one of those nomads of the bush who make a living by trapping or poisoning rabbits, foxes, eagles, and dingoes, the first for the skins, foxes for skins and scalp money, and the scalp money for dingoes and eagles, but he wouldn’t miss a kangaroo if he had a chance, or a water rat either for that matter.

Allen T. Elliott. ‘The Trapper. Nomad of the Outback.’ Brisbane Sunday Mail, 9 January 1938, p.31.

This book explores the rapidly receding world of Australian doggers and rabbiters as they trap, shoot and poison two of Australia’s most familiar feral animals, the dingo and its mixed-breed descendants characterised in the bush as ‘wild dogs’ and the well-known feral rabbit. Two masterful authors, the late Eric Rolls and Brian Coman, have surveyed the introduction of the rabbit in Australia tracing the first introduction of this fecund creature to the First Fleet in 1788 with later documented introductions in 1791, 1825 (Tasmania), 1829 (Western Australia), 1834 (Victoria) and of course, Thomas Austin’s famous importation of wild rabbits at Barwon Park, Victoria in 1859.1

Eric Rolls’ famed book They all ran wild (1969) describes in intriguing detail the colonisation of Australia by introduced animals of many species while the Victorian research scientist Brian Coman’s droll Tooth and Nail: The story of the rabbit in Australia (1999) blends anecdote and science to update and expand on the story of Coman’s ‘underground mutton’. Coman develops Rolls’ startling 1969 revelation that rabbits had propagated and spread throughout the mainland colonies and Tasmania, not by their own fecund nature, but by intentional introduction by colonists. However, the mythology of the creation of Australia’s rabbit plague from Thomas Austin’s Christmas Day 1859 release of rabbits on his Barwon Park property has entered the national consciousness. This anecdote has burrowed deep and seems likely to remain.

Two intertwined themes of the social and cultural practices of dogging and rabbiting are identified; one is the lucrative business of gathering, bundling and selling of their pelts and carcasses and the other is practical, examining the day-to-day (and night-to-night) shooting, trapping and poisoning of wild dogs and rabbits. And not infrequently, the hunters poison or shoot one another. Australia-wide surveys of contemporary regional and city newspaper accounts and memoirs are used to describe the mores and manners of Australian rabbiters and doggers as they work their deadly way through Australia’s feral animal population.

Most Australian methods for dealing with feral animals have their earliest parallels in the British Isles including the trapping, shooting, net-drives and poisoning of rabbits. While these practices influence some of Australia’s methods for feral animal control, the United Kingdom never faced the plague proportions of rabbits or wild dogs found in our continent.

Rabbiters in the northern region of South Australia, 1907. The Searcy Collection, State Library of South Australia. no.PRG 280/1/4/241.

The commerce of rabbiting for carcasses and pelts also has a strong trade link with Britain as much of the highly profitable collecting, sorting and shipment of Australian rabbit skins went to London markets. Native animal pelts including koalas, water rats, the Central Australian golden mole and possums were part of the Australian fur trade. The record export year for rabbit pelts was 1926 when 134,024 CWT (6.8 million kilos) of rabbit hides were shipped. The hide economy was paralleled by the manufacturing and sale of tinned Australian rabbit for retail sale with the Melbourne-based McCraith’s factories exporting rabbit meat to the British grocer Sainsbury’s at a rate of 32,000 cased rabbits per week in the late 1940s.2

The circumstances, methods and motivations surrounding the destruction of Australian feral animals produced formal and informal animal control practices that continue to startle outside observers. The assignment of ‘feral’ or ‘vermin’ status to animals loosens the boundaries of acceptable behaviour, particularly in the context of amateur animal control measures. Surviving descriptions of rabbit drives concluding with rural men, women and children wading into a writhing carpet of rabbits to dispatch them with clubs and farm tools is an indication of a community’s revulsion at the massed population of animals. This palpable alarm is akin to the panic response that all animals, including humans, experience when attacked by a swarm of insects.

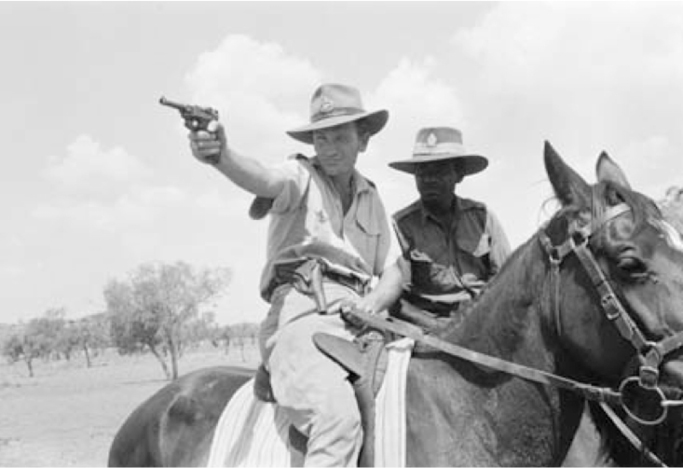

“Constable Darken of the NT Police [and his Aboriginal deputy], shoot at dingoes,” 1949. National Archives of Australia, no.A1200, L11653.

Amongst professional shooters, trappers and poisoners, extreme responses to feral animals are notable by their absence. For these men and women, this is their livelihood and memoirs and accounts often illustrate real sensitivity to animal suffering.

The public perception of the solitary rabbiter or dogger working in the bush is entangled with the romanticism of the Australian bush, the dusty image of the wandering ‘sundowner’ and our innate fear of the dangers of the continent’s often inhospitable terrain. Rabbiting and dogging is not without overt danger particularly when the shooting of feral animals is pursued as sport. Professional hunters rarely trap, shoot or poison themselves. And with ironic detachment, the scientific community’s literature on feral animal management illustrates that professional and amateur shooting is largely an ineffective means of feral animal control.

On the other hand, the Australian statistics for accidental deaths by firearm demonstrate the effectiveness of Australian amateur hunters in killing or wounding themselves or bystanders. During the peak years of the rabbit population from 1911 to 1951, 80 to 100 Australians died annually from the accidental discharge of a firearm. The peak year was 1930 when 140 people were killed by firearm accidents. Hunting was an extreme sport.

While the bush certainly had its natural dangers, news accounts make it clear that many amateur hunters were accidently (and intentionally) shot by their companions. Perhaps because of this grim reality, many professional doggers and rabbiters preferred to work alone. One of the most persistent observations of the rabbiter and dogger is their preference for solitude and what the public interpreted as eccentric behaviour. As Ernestine Hill observed in her 1937 book on the Australian bush wanderers, The Great Australian Loneliness, they were ‘the legion of the lost ones’.3 The preference for isolation that characterised many professional feral animal hunters has made ‘Rabbito Bill,’ ‘Hawky Bob’ or ‘Old Pete’ figures of fun as well as fear in the newspapers of the day. The desire for solitude inevitably fosters suspicion; always hinting at the possession of secret knowledge.

Rabbiters and doggers were (and in some cases remain) notorious for their unique trade, particularly in the arcane world of odoriferous dog baits formulated to draw the animals to the traps. A dogger’s elixir, always secret, easily surpassed the contents of a witch’s cauldron. Observers marvelled at the mixture of magic, local knowledge and bush-craft used by the professionals. As one newspaper correspondent wrote in 1925, ‘Some trappers use aniseed, or take some of the earth from the place where a tame dog sleeps. “Hawky Bob” has a special mixture of his own, but he keeps it secret. Certainly it is most effective in enticing dogs, and has the opposite effect on human beings.’4

While the professionals never hesitated to use any means to harvest rabbits and wild dogs with their guns, traps, poisonous gases, powders and baits; for the rabbiter, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation’s (CSIRO) introduction of Myxomatosis into the Australian rabbit population in 1950 took them aback. The disease had repugnant visual effects on its victims. In areas where the virus thrived, the rabbit population was decimated. But the rabbit soon had its own lobbying groups.

In Tasmania, the Burnie Trades and Labor Council ‘disagreed’ with the decision to spread the virus arguing, ‘The introduction of Myxomatosis would be a blow to trappers who depended solely on rabbits for a living.’5 While there was a modest display of sympathy shown for professional rabbiters, the carcass market and the rabbit pelt dealers; the gravity of Australia’s rabbit problem overcame commercial resistance. In Queensland, dark suspicions were voiced by a chapter of the Graziers’ Federal Council that Commonwealth efforts toward eradication by Myxomatosis were under threat from the rabbit industry. ‘We have information that certain interests are taking very active steps to prevent [rabbit] eradication in Australia . . .’6 Despite some reservations, the rural Australian rabbiting culture was annihilated in the 1950s where the Myxomatosis virus was able to spread easily. In other areas where the conditions and weather did not support the insects assisting the seasonal spread of the disease, the rabbits and the rabbiters continued their 100-year war.

“Rabbits around a waterhole during Myxomatosis trials at Wardang Island, South Australia,” 1938. National Archives of Australia, no.A1200, L44186.

Wild dogs have never suffered an introduced disease-borne assault and in recent years, commentators and press reports continue to insist the wild dog population is increasing in many areas. In Western Australia and Victoria, for example, recent state-funded campaigns have encouraged the dogging profession with funding and bounties, while some Australian shire councils retain professional dog hunters. Shooters, trappers and ‘Dog Stiffeners’ (doggers using poison baits) continue to practice their trade. The use of poison, especially a commercial product known as 1080 (sodium monofluroacetate), is currently favoured and is dropped by aircraft over inaccessible areas where wild dogs are thought to thrive. Ernestine Hill’s Great Australian Loneliness suggests pursuit of the lucrative wild dog bounty money in the early decades of the 20th century drew Europeans deeper into Australia’s vast bush geography well in advance of conventional settlement.7

It is generally accepted that shooting wild dogs is a sporting activity for astute amateur doggers. ‘. . . [T]he man who shoots a dog is lucky,’ writes one experienced 20th century bushman. . . . ‘[S]hooting is a slow game, the dogs are too cunning; their sense of smell too acute. Gunpowder is just a danger sign. Hence poisoning and trapping are preferred.’8 What proved true of dogging in 1925 remains true in the 21st century.

While wild dogs may be abundant in some rural areas, the subsidiary wild rabbit market for skins and carcasses never fully recovered from the introduction of Myxomatosis. In 1995, the escape and subsequent distribution of the Rabbit Calicivirus Disease (RCD) once again battered a modestly rebounding wild rabbit trade. But during this same period, the market trade in domestic rabbits produced sales of $9 million.9 To prevent domesticated rabbit escapes, Queensland and the Northern Territory have banned rabbit farming but in 2015, it remains legal in other states. In 1999, 115 commercial rabbit farms were recorded.10 Brian Conan’s 2010 edition of Tooth and Nail also notes the modest revival of rabbit trapping and shooting. Foster and Telford’s 1996 report, Structure of the Australian Rabbit Industry noted professional rabbiting is more common in the arid areas of Central Australia where biological agents are less effective. While reports are mixed, there is evidence rabbiters remain active in areas of New South Wales and Victoria.

Despite over a century of government funding, professional and amateur hunting, broadcasting poisons by machine, gassing, hand and aerial drops, ingenious traps of every description and an international community of scientists devoted to their destruction, the rabbit and the wild dog sit firmly in their niche in the Australian ecology. On the other hand, the Australian rabbiter and the dogger are slowly making their way toward the door. This study seeks to preserve some of the cultural and social ethnography of these professions before they become extinct.