Chapter 2. Sport Shooting and Rabbiting in England and Australia

As the rabbits are put up [by the dogs], they cut in and out of the runs and require great quickness of eye to catch them before they are lost to sight. Great care must be taken not to shoot the terriers . . .

‘Stonehenge.’ Manual of British Rural Sports, G. Routledge & Co, London, 1856, p.66.

Most Australian rabbiting traditions have their origins in Britain and although rabbits are a 12th century introduced species in Britain, they were considered valuable assets in the British Isles. Their warrens were encouraged and in some cases, constructed for the sole purpose of rabbit farming.1 The commercial market for British rabbits was later undermined by Australian imports of meat and pelts, which led to the collapse of local culling. By the end of the 19th century, the rabbit in the United Kingdom was increasingly described as a rural pest.

In the 20th century, the rabbit was considered a serious UK agricultural problem and in 1933, trapping controlled an estimated 50 million rabbits.2 Haddon-Riddoch’s survey in Rural Reflections demonstrates the vocabulary of pest animal destruction includes the familiar labelling of rabbits, squirrels, raptors such as hawks and eagles, foxes and cats as ‘vermin’. Gamekeepers were employed to suppress them through poisoning (including gassing), trapping and shooting.

On the other hand, hunters who pursued the animal for sport generally used beagles, cross-bred ‘lurchers’ and terriers to flush the rabbits and to pursue them for shooting.3 Good dogs and the ability to lead and shoot a running rabbit are necessities in this style of hunting and shooting accidents with dogs and occasionally, fellow hunters are not uncommon.4

‘[I]n rabbit shooting, rapidity of execution becomes indispensable. . . . We have many times met with these squirting diminutive creatures in the fields, and generally succeeded in stopping them, but only when they presented what might be called fair shots. Some years have elapsed and indeed the effects of “time effacing finger” has been rendered manifest . . .’5 That is, as the writer acknowledges, a quick hand and eye is necessary to kill a bounding rabbit.

Trapping is also used. Side-stepping the topic of rabbit snares, a practice seldom found in Australia, the British toothed spring steel trap was often described as a ‘gin’ (engine) as early as the 17th century and the trap later adapted to small scale manufacturing in the late 18th century. Many of the British spring traps were exported to Australia where traps such as Tonks (est. UK 1827) and Henry Lane (est. UK 1851), later manufactured as Henry Lane Australia in Newcastle NSW (est. ca.1920), became generic terms as in trappers ‘setting the Tonks’.6 The use of traps for rabbit control was a contentious issue in the United Kingdom as it was thought that trappers ‘had no interest in exterminating rabbits, as against “cropping” them’.7 This was an accusation echoed in Australia. ‘To eliminate them would be contrary to the trapper’s interest . . .’8

The Collington Patent Rabbit Net Device (1940)

After the drive is over, the operator should run along the net and despatch the rabbits at once. They are usually found hopelessly entangled and in order to kill them, grasp the head firmly in one hand and the shoulders in the other and force the hands together, thus causing death instantaneously.

Stuart Haddon-Riddoch. Rural Reflections. A Brief History of Traps, Trapmakers and Gamekeeping in Britain. Argyll Publishing, 2006 edition, p.369.

Driven by humane considerations, UK restrictions were placed on spring traps in 1939. Only a small number of spring traps are allowed in Britain. They must catch and kill humanely in 85 percent of activations and be set within the opening of a burrow or warren entrance.9 The appearance of Myxomatosis in Britain in 1953 decimated the spring trap industry. A total ban on this type of trap in England and Scotland occurred in 1958 and new regulations in Northern Ireland in 1969 finished the practice. Spring traps with modified ‘humane’ jaws can now be used within an enclosure or inside the warren tunnels but not outside the warren entrance.

In areas where the rabbit population was high, rabbit drives were an alternative and commercial rabbit drive nets remain available in Britain. These textile nets were set up on poles and suspended prior to dawn and evening feeding, then dropped and the rabbits driven into the net for killing or capture. The nets could be as long as 150 metres.10 Long-netting, a nocturnal (and occasional daytime) practice that relies on dogs and beaters to corral the rabbits into a mesh net is still practised.11

Chemical and Germ Warfare

The British sentiments toward wildlife forbade the wholesale poisoning regime found in Australia. The British Protection of Animals Act, 1911 made it an offence to set poison baits for rabbits. Poison baiting remains banned but its revival is occasionally discussed. But by the late 1930s, trapping and snaring was failing to control the rabbit population and new legislation in the form of the Prevention of Damage by Rabbits Act, 1939 allowed the use of fumigants in burrows. Some authorities suggest that the use of poisonous gases on rabbit burrows drew on the expertise earned in the chemical warfare of the 1914–18 War.12 Fumigants such as ‘Phostoxin’ (aluminium phosphide) and the cyanide-based agents Cymag (withdrawn in the UK 2004) and Cyanogas (USA) were amongst the favoured chemical methods of rabbit control. A more effective agent, however, awaited in the wings.

STOP the deliberate spreading of MYXOMATOSIS! Victims of this horrible disease, blind, misshapen, tormented, are being caught for sale as carriers to be let loose in infection-free areas.

RSPCA Advertisement. The Times, London, 17 September 1954.

After Myxomatosis appeared in Britain in 1953 (as with other unwholesome practices, some suggested it was introduced from France), the arrival of the disease was applauded by agriculturists but abhorred by animal protection organisations such as the Royal Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA). The Pest Act of 1954 successfully forbade its official distribution, largely to protect the domestic rabbit industry but it continued to spread with rumours of assistance by landowners.

Australian Sport Shooting and Rabbiting

While most of the features of Australian rabbit control such as rabbit shooting for sport, the rabbit drive, trapping and poisoning have precedents in Britain, the development of the Australian variant of the ‘rural sport’ of the hare and rabbit hunt is typically assigned to the property of Thomas Austin, Barwon Park, near Geelong, Victoria. When 12 pairs of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) were introduced to Thomas Austin’s Barwon Park estate in 1859, authorities agree sport shooting was Austin’s aim. The estate is, of course, Ground Zero for the feral rabbit population in Victoria. Although Austin encouraged sport shooting amongst his friends and acquaintances, well-documented Royal visits from the Duke of Edinburgh in 1867 and 1869 provided ample insight into the practice of sport shooting.

The Melbourne daily newspaper The Argus reported the Duke’s celebrated 1867 shooting party killed some 1000 rabbits on Austin’s property in less than four hours with his ‘Royal Highness’ accounting for an improbable 416.13 Two years later The Argus describes another day of sport with men ‘beating up’ the rabbits into wire netting and driving the animals past the shooters. Two days of shooting accounted for some 1567 rabbits with 432 claimed by the nobleman. The Duke of Edinburgh’s visits also illustrate the challenges of hare shooting when compared to the European rabbit. While hares (Lepus europaeus) were less numerous on Barwon Park, on this occasion only three were bagged after two days of shooting.14

A flock of emus were also driven past the Archduke [Franz Ferdinand d’Este] who succeeded with the rifle in killing a very fine specimen and wounding another, which was afterwards secured. The feature of this day’s sport was the wild turkey shooting.

‘Shooting Excursions in the West.’ The Sydney Mail and NSW Advertiser, 27 May 1893, p.1096.

But by 1868, the Australasian was reporting, ‘the [Barwon Park] rabbits are becoming far too numerous on the estate. Netting has been constantly going on but it has been found impossible to keep them down. They are literally becoming a nuisance over the country.’15 Fateful words.

While the Duke of Edinburgh’s sport shooting set a high standard, the 1893 visit of Archduke Franz Ferdinand d’Este, later the ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to grazier Frank Mack’s Narromine Station NSW far surpasses the breadth of animal slaughter established by the British Duke. A report in the Sydney Mail records that on 24 May, Archduke Franz Ferdinand shot five kangaroos, several ducks, pelicans, ibis, cranes, eagles and hawks. Moving onto other nearby Mullengudgery properties, his Excellency shot a flock of emus and wild turkeys. No rabbits are recorded.16 Later visiting Moss Vale, he bagged platypus and koala, and by night, he shot kangaroo, possum and finally, rabbit.17

Outside of the well-documented sport shooting of the nobility at Barwon Park and elsewhere, amongst the general population, Australian rabbiting traditionally took three forms: covert (thicket) shooting, hedgerow hunting and open country hunting. ‘[The] underwood and long grass [coverts] hold rabbits in plenty . . . If coverts be absent, there are the big tangled hedgerows with deep ditches and patches of bracken covering the banks here and there.’

Barwon Park Homestead, Inverleigh Road, Winchelsea, Victoria, n.d. ©Brian Lloyd Photographer. Australian Heritage Photographic Library, Commonwealth Department of the Environment, no.rt70455.

‘Where rabbits lie out in cover a couple of good terriers, seasoned dogs, are your best assistants. . . . The rabbit shoot in covert is a scene of much vivacity and noise, and of not a little criticism on shooting. The beaters and terriers make things hum. The guns command the open spaces and rises. And very fine shooting is often seen. . . . On the other hand, the ambitious and the impetuous . . . endeavour to follow suit . . . and not seldom the yell of man or dog who has been hit instead of rabbit . . .’18

While hedgerow cultivation is unusual in mainland Australia, it was notably popular in Tasmania where ‘hedgerow hunting’ with terriers is also described as great sport with two shooters, one on each side of a hedge, standing and waiting for the dogs to flush a rabbit. ‘What splendid sport, too, a small furze [gorse] brake, hunted from end to end by a couple of . . . dogs, the shooters standing well out on each side on the grass so as to command a wide area. Not seldom a big hare canters out in a leisurely fashion, for all sorts of furred and feathered creatures love a furze brake which woods and fields surround.’19

‘If covert or hedgerows are not available,’ writes the enthusiast, ‘some shooters lend a begrudging credibility to the use of ferrets to flush rabbits from warrens but with a multitude of burrows, an escape can go un-noticed. The sporting rabbiter is not fond of ferreting, preferring to leave it to the children.’20

Open country shooting is less reliant on dogs, but requires a degree of stealth, plentiful rabbits and a particular awareness of the placement of the other hunters. For city-based hunters, suburban trains in Victoria could be taken to open country suitable for rabbiting.

The Argus offered similar advice to its Melbourne readers in 1910 advising hunters where they could get ‘good rabbit or hare shooting’ within a reasonable distance of the city. Diggers Rest on the Bendigo line was recommended and The Argus advised, ‘It may be necessary to have permission from landholders. Rabbits are plentiful . . . When hare shooting on a windy day always follow up a watercourse or other depression, working against the wind. Hares invariably shelter in these hollows on windy days. If you wound a hare, follow it up. When hard hit, they will run strongly for a considerable distance, then roll over and are dead before you get to them.’21

Rifles and Shotguns

The earliest accounts of rabbit hunting in the popular press in the 19th century suggest that the shotgun was initially the favoured weapon for sporting shooters. Henry Lawson’s 1901 short story ‘A Hero in Dingo Scrubs’ describes a selector’s firearm as ‘a double-barrelled muzzle-loader, one barrel choke-bore for shot and the other rifled’.22 Today, this firearm survives as an ‘over and under’, commonly a single barrel shotgun paired with a small calibre rifle.

Shotguns are frequently identified as villains in hunting accidents. In an April 1896 incident in Mt Franklin, Victoria, a hunter in a party of eight shooters was killed when the shotgun of one of his companions accidentally discharged into victim’s abdomen. Thirty shot were extracted by the doctors suggesting that light shot (no. 6 shot commonly favoured for rabbits) was used.23

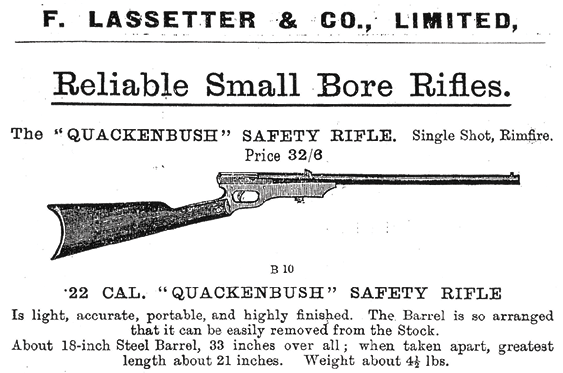

By the first decades of the 20th century, the Sydney Morning Herald’s ‘On the Land’ columnist suggests that a small calibre rifle is now favoured by ‘Young Australia’ and his observation can be correlated with the cost of ammunition.24 In 1902, 100 12-gauge shotgun shells retailed for 8/6 (2014 equivalent $57) for 100 preloaded cartridges while a box of the cheapest .22-calibre cartridges was 1/6 (2014 equivalent $10) per 100 at F. Lassetter & Co.25 The BSA .410 shotgun also gets some attention by sporting writers. ‘My own boy, 12 years old, has been using one since his 9th birthday,’ writes one commentator.26

Rabbit shooters, Northampton, Western Australia, 1947. Battye Library, State Library of Western Australia, no.001336D.

Some sporting writers claimed ‘Young Australia’s’ .22-calibre rifle could bring down rabbits at 150 to 200 yards (137–182 metres) but 100 yards (91 metres) seems a more realistic estimate.27 Retail catalogues offered lever-action, single-shot and pump-action .22-calibre rifles at an accessible price for working youths. Responding to increasing shooting accidents in Victoria in the first decades of the 20th century, it became unlawful to sell cartridges to shooters under 18-years of age. The 1920 regulation was unpopular and ‘It is none the less a fact that . . . many storekeepers take no trouble and the law on the subject is widely ignored.’28

The colloquial term ‘Pea rifles’ is occasionally used to refer to the single-shot .22-calibre rifle that must be reloaded after each discharge, but ‘Pea rifle’ optimistically suggests that this is a less than dangerous weapon. News accounts of the era demonstrate that this was not the case and the small calibre weapon was considered by some commentators to be a menace. Restrictions were also placed on their sale to young Victorian shooters in 1912.29 The Feldheim, Gottheim Sydney catalogue’s offered the ‘Quackenbush Safety Cartridge Rifle’ firing .22-calibre cartridges and in their Quackenbush ‘air gun’ models for ‘BB’ shot or in a pinch, dried peas.30 This may account for the colloquial ‘Pea rifle’ appellation and the confusion in the public mind.

Quackenbush safety cartridge rifle, .22 calibre. Available through the F. Lassetter & Co. Catalogue and the Feldheim, Gottheim catalogues in the first decade of the 20th century.

Rabbit hunting with a rifle soon evolved into a financially accessible sport while trappers began to dominate the rabbiting trade as the rabbit plague expanded and the business of harvesting and exporting Australian rabbit skins and fur grew to 100,000 CWT (1 CWT=50 kg) in 1906–1907.31 Hobby shooters were far more likely to damage the pelts, especially with shotguns. The Sydney Morning Herald wrote in 1910 that ‘. . . [A] man who goes out to shoot for sport does not nowadays shoot rabbits with a shotgun, but uses a magazine rifle of small bore.’32

Pursued by dogs, ferrets, rabbit drives, trappers, poisoners, rabbit warren diggers and shooters, the rabbit became a target for Australians of all ages. In suburban Victoria, rabbiting grew to such proportions that special trains for shooters were scheduled for the weekends.

Rabbit shooting and picnicking party. South Australia, ca. 1900. State Library of South Australia. “South Australian Scenes”, no.B71250/22.

Rabbiting: An Extreme Sport

Armed rabbiters, many of them young and inexperienced, soon proved a menace to each other and to livestock. The Sydney Morning Herald rural writer commented in 1906 that ‘Young Australia uses a small rifle, and with a split sight he can do some remarkable shooting. Unfortunately he too often shoots his comrade by mistake; indeed, the list of casualties with these little rifles is appalling.’33 Australian newspapers in the first half of the 20th century seemed to revel in the rising death toll, with Melbourne’s The Argus frequently waving the bloody shirt.

In Bacchus Marsh, a favoured spot for Melbourne’s hunters, The Argus reported Irvine Prealand, 21 years old, was found dead, having shot himself crossing a fence, a perennial scenario for shooting accidents.34 A toddler in Fawkner, Victoria was wounded in the back by a .22-calibre bullet from an unidentified Merri Creek rabbiter as recently as 1952 while playing in front of his house.35

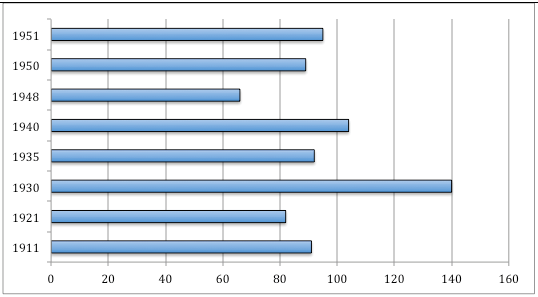

Accidental Deaths by Firearms in Australia. Source, Australian Statistical Yearbooks, 1911-1951.

Livestock was also under threat from the rabbit shooter plague and a Keyneton, SA grazier reported the loss of a ram and the wounding of a horse from rabbit hunters.36 Shooting rabbits by spotlight was reported in One Tree Hill in the suburbs of Adelaide as early as 1925 when ‘carloads of shooters’ were stampeding stock by driving along the roads of the district and firing into neighbouring properties.37

Displaying amazing dexterity, a reckless West Australian rabbiter fired at his quarry from his moving lorry missing the rabbit but striking a passenger on the passing Merriden Express train near Grass Valley, WA. Passengers on the train were able to record the lorry’s registration number and the driver, Eli Goode, was arrested. While Goode admitted to police that he shot at a rabbit, he claimed he did not see the train.38

While rabbit shooting this morning with a party of friends [on the Rivolo Beach], Clarence Victor Faulkhead, 28, of Forster-street, Lancaster, near Woodville [South Australia], was shot in the back by a pea rifle, and died 2 minutes afterwards.

‘Shot by Pea Rifle.’ The Mercury, Hobart, 25 April 1927, p. 9

No experienced shooter will be surprised at carelessness with firearms but the Launceston Examiner reported with astonishment that a New Zealand rabbiter fired his shotgun at a rabbit just visible over the crest of a hill but found to his surprise that he had shot the hat of a Miss Collinson who was sitting with her lover. The young lady and her companion Ernest Crooke were taken to the hospital.39

The number of recorded deaths by accidental discharge of a firearm, while not directly attributed to rabbiting in the statistics, closely follows the volume of sale of rabbit skins and carcasses. This suggests that the popularity of rabbit hunting correlates with deaths by firearm.