Chapter 3. The Australian Skin Trade

Mr George Patterson, who trades [as] the Tasmanian Fur Depot, [Launceston] [has] a splendid show of fur hearth rugs. A very attractive one is made of Tasmanian tiger skins, now quite uncommon.

‘Tasmanian Furs.’ Launceston Examiner, 6 March 1908, p.7.

Australian wildlife, indigenous and introduced, has been harvested for commerce and personal use for centuries, first by Aboriginal Australians, later by Eurasian colonists. This includes the fur pelts of animals such as the native water rat (Hydromys chrysogaster), possums, the illusive southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops), Tasmanian tigers, foxes, rabbits and koalas (the latter often described in the press as the ‘native bear’).1 Commercial uses were uncommon for wild dog skins. Scattered references can also be found for the pelt of the rarely sighted platypus.2

In the 1880s, it was reported that as many as 300,000 koala pelts were exported for the London fur exchange. In 1906, a koala pelt could bring 19 pence (2014 equivalent $11), dependent on the fluctuations of the European market.3 Australians would be surprised to learn that koalas continued to be hunted for their pelts until the early decades of the 1900s when state governments began to introduce legislation to protect the animal. In 1919, a million ‘bearskins’ were recorded in a six-month shooting season in Queensland.4 The fictional shooting of ‘bears’ is a commonplace activity in the Steele Rudd tales of farming with ‘Dad and Dave’ published 1899–1906.5

Following a public campaign and petitions, on 10 November 1927 the Commonwealth Government stopped issuing permits for the export of koala skins.6 Koala pelts continued to be used locally, however, and examples of koala skin items can be found in Australian museum collections.7 In 1940, the Sydney Morning Herald reported there were ‘thousands’ of Queensland koala skins held by furriers in the United States and there was a short-lived gesture toward repatriation of the pelts.8

Koala skins (3600 units) destined for the fur trade. Clermont, Queensland, ca. 1927. G. Pullar, photographer. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, no.18937.

In addition to their novelty, Tasmanian tigers were also sought exclusively for their skins. In 1809, the nature painter J. W. Lewin produced a watercolour titled ‘A newly discovered animal of the Derwent’ drawn from a Tasmanian thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) skin owned by the colonial Lieutenant Governor William Paterson.9 Photographs of a Tasmanian tiger buggy rug survive in Hobart’s Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. This rug assembled by the thylacine trapper Robert Stephenson in the Evandale region ca.1903 contains eight animal pelts.10 Tasmanian news accounts record their use for coats, car mats and hearth rugs.11 Tasmanian tiger skins were trading at 20 shillings (2014 equivalent $129) in 1910–1920.

In service of the Australian fashion trade, pelts were sought from the native water rat and the Central Australian marsupial mole (southern marsupial mole), a mole discussed in the bushman Walter Smith’s Central Australian memoir describing the Aborigines of the Bloods Creek region, near Dalhousie, South Australia ‘bringing the beautiful gold pelts of the marsupial moles in from the sand hill country to [trade] at Bloods Creek’.12 These golden mole pelts were made up by furriers and available at Weidenhofer and Co., Adelaide as ‘collars, boas, capes, muffs, cuffs, slippers, footwarmers’ and other clothing items.13

The Golden Mole (Notoryctes typhlops) Drawn by Rosa Catherine Fiveash, ca. 1891. Lithograph for the South Australian Government Printing Office. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, vol. 14 (1890-1891).

Far to the southeast of Smith’s Central Australian homeland, the water rat, an animal with a dark brown to grey brown pelt with lighter underbelly fur, was sought by bush trappers in the Murray River and its tributaries.14 The pursuit of both of these animals seems based on supplying the fashion industry and at present, no export figures could be found.

With the export of koala pelts prohibited, possum and fox pelts soared in importance with an export figure of 183,018 possum furs and 2083 fox pelts shipped in the boom years of Australia’s international fur trade in 1953–54.15 Export figures for these furs are modest, however, compared to the volume of the pre-Myxomatosis rabbit pelt shipments in the mid-20th century with claims of 4,319,346 units exported in 1953–54.16 The large-scale trapping and the shooting of rabbits were initially driven by the profits from the sale of rabbit carcasses to the public and the skins to wholesalers. The destruction of wild dogs was encouraged by the bounties offered by Pasture Protection Bureaux or by the wages offered to ‘doggers’ by property owners.

There was considerable dissonance between eradicating the ‘rabbit menace’ and the commercial imperatives of the ‘fur trade’. This issue was discussed at length in the press. David Stead, the former NSW ‘Special Rabbit Menace Inquiry Commissioner’, published a bellicose pamphlet in 1935 arguing the ‘great demand for rabbit skins in recent years, have done more to sustain the rabbit menace in the worst-infected districts . . . of New South Wales and perhaps Victoria . . .’17

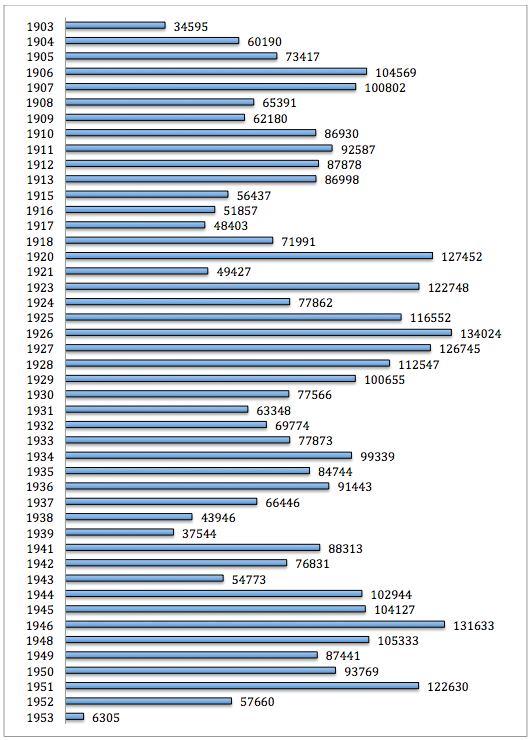

Australian rabbit skins exports by CWT (UK CWT = 112 lbs/50 kgs). Source, Australian Statistical Yearbooks, 1903-1953.

Stead describes the practices of the ‘rabbit trade’ as wasteful and counter-productive in controlling rabbit numbers. ‘No one can expect the rabbiter to stay to catch the last rabbit . . . The rabbiter is there, and will be there, just as long as there is a sufficient quantity of rabbits to provide the maximum number of skins . . . at satisfactory prices.’18 As an active agent in controlling the population, the trapper and poisoner only ‘takes the top off’ the rabbit numbers.19 The fur trade, he argues, perpetuates the rabbit menace.

Dingo pelts, Rockmount, Queensland, 1935. Photographer unknown. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, no.135132.

The pelts of dingoes (often called the ‘native dog’) and interbred wild dogs have, in the past, had a very modest commercial value in the fur trade with the exception of bounties paid for their scalps or occasionally, for their skins. As one Central Australian traveller noted, ‘The token, on which payment of the bonus is made, is a scalp, and [throughout the Centre] scalps have now become a sort of currency, filling the same place in the intercourse of the two peoples as the beaver skin formerly did in the territories of the Hudson’s Bay Company [in Canada].’20

The South Australian Register, however, was reporting in 1895 that the Adelaide retailer Weidenhofer and Co. was offering for sale rugs made up from the ‘yellow dingo’ and the ‘black dingo’ for sale. The furs were assembled by H. Lawrance, furrier, Rundle Street, Adelaide.21

Wild dog hides found more arcane uses and the Brisbane Sunday Mail in 1933 reported professional trappers fashioning and wearing scent-masking gloves and slippers of dingo hide while baiting and setting their dog traps.22 Wild dog hides have also been tanned and made into floor rugs, saddlebags and carriage rugs and wild dog hides in excess of 1700 millimetres are recorded. An Aldinga, South Australia carriage rug (2150mm x 1340mm) made from 12 dingo skins by James Pridham and ornamented with four dingo tails is in the National Museum of Australia, Canberra.23