Chapter 6. The Rabbit Business

Two tins of preserved rabbit, believed to have been tinned 55 years ago were recently found by three men while carting dirt from the site of the old [preserving] factory. One of the tins was described as being as fresh as ‘right out of the burrow.’

‘Rabbits tinned 55 years ago found.’ Camperdown Chronicle, Victoria, 1 April 1948, p.1.

On the return to a rabbiter’s camp after a night of trapping, the rabbits are usually bled and gutted before rigor mortis occurs (typically between one and a half hours to three hours), then sold in the hide to carters who truck the carcasses to regional chillers for grading and sale. Typically, the carcasses are ultimately graded on age, condition of the meat, cleanliness and the quality of the hunter’s gutting and bleeding process. When the carcasses reached advanced rabbit processing plants, the employees worked in a factory system of moving overhead chains and hooks for the suspended rabbit pairs. They laboured on piecework rates ‘heading and tailing’ the animals before skinning.

Coman’s Tooth and Nail: The Story of the Rabbit in Australia, reveals that a tinned rabbit meat factory was in operation in the rural town of Colac, Victoria as early as 1871.1 Their product was ‘jugged hare’, a thankfully extinct process where the entire animal (sometimes dismembered) is stewed for several hours in a sealed container. In the Colac factory, where 40 workers toiled, the rabbits were jugged in lead-soldered tins.

An 1898 account of the Mount Gambier Rabbit-Preserving Company, Compton, South Australia claimed that their trappers worked within a radius of 20 miles (32 kilometres) of Compton. The pay was 3 1/2d to 3 1/4d (2014 equivalent approximately $1.80) for a medium-size pair. The journalist reported, ‘The trappers are said to make fairly good wages at the prices they receive, few of them earning less than £2 a week (2014 equivalent $287). . . . I was told that at times the earnings of some especially expert or very lucky trappers greatly exceeded even this amount. In April of this year the company paid over £700 (2014 equivalent $100,000) for rabbits.’2

The Advertiser’s journalist describes the processing of the Mount Gambier rabbits with awe. ‘This work is done by two men with most marvelous celerity,’ the writer observes. ‘One worker chops off the heads and fore and hind legs up to the first joint and passes the carcasses on to the other, who skins them with the assistance of a hook fixed on the wall in about four movements of the hands. I never saw any thing so quickly done . . . The bodies are then passed through an opening into the kitchen where they are gutted and thoroughly washed, and then pickled for some 12 hours. The next operation is scalding in boiling water heated by steam, after which they are drained, weighed, and put into 2-lb. (900 gms) tins, about a rabbit and a half usually going to a tin. The contents are firmly pressed into the tin with a screw arrangement, and the tin is passed into the soldering shop, where the top is soldered on.’ The Mount Gambier rabbit-preserving cannery export brands were ‘Jack Frost’ (first quality) and ‘Bunny’ (second quality).

Mt Gambier Preserving Works, Compton, South Australia, 1898. Compton Collection, State Library of South Australia, no.B 16874.

Dependent on condition as well as supply and demand, some authorities cite rabbits selling for a 1/ (2014 equivalent $4.50) a pair in 1917.3 In wartime Melbourne in 1944, rabbits were selling at the wholesale market at 1/6 (2014 equivalent $5.60) for a young pair and 2/ (2014 equivalent $7.50) for a large pair.4 Careful and rapid handling of the rabbit carcass was critical for the best retail price. The winter season allowed rabbits from further afield to reach the markets by rail or lorry and remain in ‘bloom’ or good condition. The introduction of the mobile ‘chiller’ in the mid-1940s soon brought major efficiencies to rabbit trapping and processing by making some regional chilling plants redundant.

Mobile rabbit refrigerating plants (‘chillers’) roamed the rabbiting districts picking up dressed carcasses for shipping to the processing centres. The appearance of these units and the demand for rabbits created a price war in the late 1940s. Some of these refrigerated chillers could hold up to 2000 pairs of rabbits and were particularly active during the winter months when the weather was bearable and rabbit pelts were lush and brought a better export price.

Marketing rabbits was attractive to rural entrepreneurs. The late mayor of Mildura, Victoria, W.J. (‘Jim’) Christie (d.1979) bought into the rabbit-buying industry following a lottery win after spending some years as a rabbit trapper; he was amongst the first to work with mobile chillers. Based in Mildura but ranging into South Australia, Christie was a familiar figure amongst the ‘lantern swingers’ and fondly remembered for his casual philanthropy.5

Navef Ayoub, Rabbit skin buyer, Dubbo NSW, ca.1905. State Library of NSW, At Work and Play, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, no.bcp_05141.

Frank McCarthy, another rabbit buyer active in South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales in the mid-20th century, argues the Melbourne-based rabbit exporters J. A. & G. McCraith (Jack and Gerald) were the first to introduce mobile chillers (refrigeration plants) to the rabbiting trade.6 He recalls that the McCraiths (Jack was informally known as the ‘rabbit king’) operated 73 mobile chillers in Victoria, 65 chillers in South Australia and 48 in New South Wales.7 Some sources claim that the McCraiths operated as far as the West Australian borderlands to keep up their supplies to their South Melbourne processing factory.8 The Carlton, Victoria small-goods processor, Norman Smorgon and Sons were initially amongst their major purchasers until Smorgons also became rabbit buyers. The McCraiths exported rabbits to the British grocer Sainsbury’s at a rate of 32,000 cased rabbits per week in the late 1940s.9 J. A. & G. McCraith are also said to have held the last rabbit export license in Victoria.10

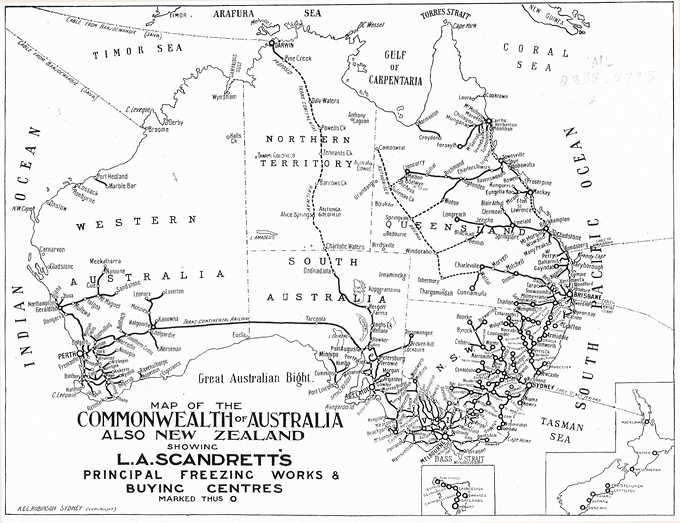

L.A. Scandrett, J.C. Earle, William Angliss & Company and others also exported rabbits.11 These businesses had offices in the capital cities and a network of freezing depots also located in regional centres. G.B. Eggleton claims that in the mid-1930s, 15,000 to 25,000 pairs of rabbits were being handled weekly in Mildura, Victoria processing plants.12

L.A. Scandrett’s rabbit freezing works and buying centres (Australia and New Zealand), ca.1917. Prospectus, L.A. Scandrett, 4 Bridge Street, Sydney, 1917.

As the speed of shipping increased, rabbit processors were also forced to pick up their handling pace. The rabbit freezing works in Oberon, NSW is said to have handled 25,000 pairs of rabbits each week in the mid-20th century. The individual skinners also held factory competitions with seemingly impossible claims of 2500 rabbits skinned daily.13 Like most processors, skinners working in the McCraith’s processing plant in the mid-20th century laboured on piecework and the ‘rabbit king’s’ biographer claims an average skinner in their Brunswick factory could skin 375 rabbits per hour.14

In the 1960s, long after the rabbit plague had subsided, the Moyston, Victoria pub continued to hold their annual rabbit skinning contest dominated for years by Ron Crawford, a former rabbit trapper, who could gut and skin a pair of rabbits and peg the hides in less than 60 seconds. Crawford, the six-time Moyston World Champion born in 1914, claimed to skin a rabbit in ten seconds in his youth. In 1986, The Age, Melbourne reported that Ray Kelly, who skinned and pegged the pelts of a pair in 72 seconds, finally ousted the 72-year old Crawford as World Champion.15 Typically, the skinners’ technique for gutting was to slit open the rabbit’s abdomen with a pocket knife (some rabbiters tore the underbelly open with their hands), then holding the head and hind legs in one hand, flicking the carcass with a whip-like gesture that emptied the abdominal cavity in one economic movement.16

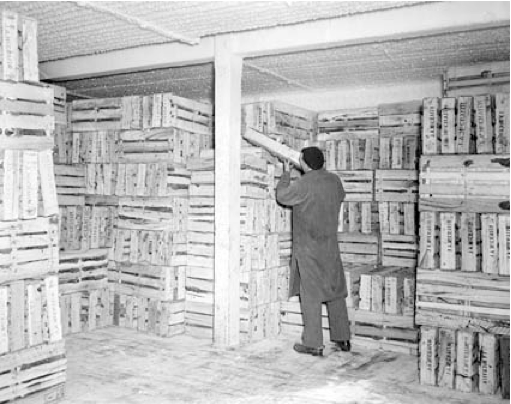

Crated rabbit carcase export, refrigerated hold on the vessel Stratheden, 1946. National Archives of Australia, no. A1200, L2659.

The rabbit industry was a major contributor to the rural economy. The historian Michael McKernan records rabbiter Geoff Sheehan working in the Jungiong NSW region in the 1949–1950 season filling 17 chaff bags of pelts for the felt market and purchasing a new automobile with the proceeds of the sale.17 Frozen rabbit was sold to overseas markets and Australian rabbit pelts competed on the world market for their quality and quantity. Exports for the international fur market waxed and waned based on fashion cycles while the domestic market for rabbit-derived felt for hat makers such as Akubra remained strong but also subject to the whimsical laws of fashion. Eight to 14 rabbit pelts are needed for a conventional hat.18 In 1995, as the CSIRO’s recently introduced calicivirus began to work its way through the Australian rabbit population, Akubra negotiated for three 60-tonne shipments of rabbit pelts from Britain. The Managing Director of Akubra reported their Kempsey NSW factory relied on 65,000 skins per week to keep abreast of hat demand.19

Rabbit skin glue also provided a local market for de-haired skins. The Davis Gelatine works in Onehunga, NZ (1881), Botany, NSW (ca.1915) and Kensington, Victoria (1931) was Australia’s premier protein glue manufacturer. Their glues were available in beads, sheet and powder. The Davis plant’s ‘GRIPIT’ was amongst their more celebrated products.20 The hide-based water-soluble adhesive is made by the recovery of collagen protein after the removal of the hair. This glue competed with other protein or ‘hide’ glues made from cattle or other animals. In the past, rabbit skin glue was also used as an ingredient of the ‘gesso’ used to prepare or ‘size’ artists’ canvas and wooden panels for painting in oils or other media. The size of the early market for rabbit skin glue is difficult to determine but it was considered a superior adhesive until it became obsolete with the appearance of synthetic glues.