Chapter 7. Germ Warfare and the Death of the Rabbit Industry

[A]n Alexandra grazier blamed Myxomatosis for the outbreak of indiscriminate shooting in his district. ‘This year, because of Myxomatosis, rifle owners have no rabbits to shoot at so they shoot at anything,’ he told the Glaziers Association. . . . ‘Many of the offenders were New Australians, indiscriminate shooters with high-powered rifles.’

‘Myxo to blame.’ The Argus, Melbourne, 15 May 1953, p.7.

Where guns, poison and traps failed, biological warfare against the rabbit proved successful. The idea of introducing a rabbit-specific disease into Australia has a speculative history extending over a century. In 1887, the use of germ warfare was given special encouragement when the New South Wales Government offered a £25,000 [2014 equivalent $3.5 million] award to ‘any person or persons who will make known and demonstrate at his or their own expense any method or process not previously known in the Colony [NSW] for the effectual extermination of rabbits . . .’1 An advertisement for the programme and the generous reward appeared in selected colonial newspapers as well as ‘leading English, American and Continental journals’.2 Amongst the many (some sources describe thousands) responses to this international announcement was a submission from the famous French microbiologist, Louis Pasteur.

Pasteur’s French laboratory responded to the competition with a variant of a bacteria isolated by the scientist, Pasteurella multocida (responsible for ‘chicken cholera’) that had been successfully demonstrated in rabbit field trials conducted in France. The bacterium attacks the respiratory system of rabbits, then the infection progresses, affecting other internal organs and ultimately the genitalia.

Alternative disease controls were also suggested. A survey in The South Australian Advertiser revealed that an Adelaide scientist, Professor [Archibald] Watson from Adelaide University attempted to bring 24 rabbits from Germany infected with a disease caused by a parasitic mite Sarcoptes scabiei var. cuniculi to South Australia in 1886 for a trial. The rabbits expired in transit.3 Professor Watson’s intent was to investigate the transmission of the disease into the South Australian rabbit population. As Brian Conan reports in his survey of the rabbit debacle Tooth and Claw, Professor Watson’s Adelaide experiments came to naught.4

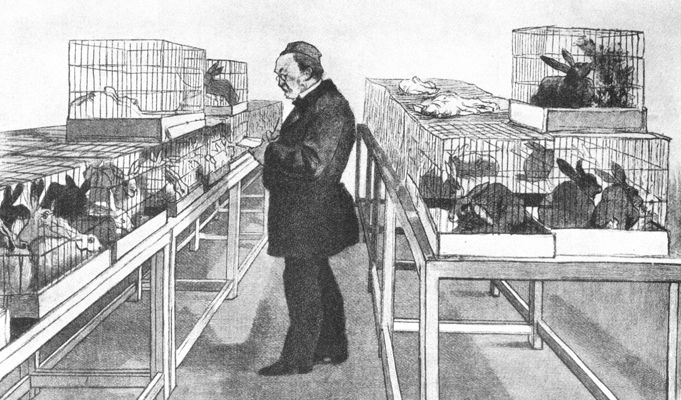

Louis Pasteur. Illustration (1884), in Mikrobenjäger [Microbe hunter]. Orell Füssli, Zürich, 1927. Courtesy André Koehne. Wikimedia Commons. 4 July 2015.

Pasteur sent a team of laboratory scientists from his laboratory to Australia to demonstrate his deadly microorganism and claim the award. The team arrived in Sydney but they were hampered by the predictably chaotic state of New South Wales governance under Sir Henry Parkes, entrenched rabbit industry interests, mountebank ‘scientists’, vigorous lobbyists and Legislative Assembly promoters of woven wire rabbit-proof fencing.

While the Pasteur scientists were given Rodd Island, Sydney Harbour for their laboratory site, the NSW Parliament’s appointed ‘Rabbit Commission’ blocked the proposed rabbit control field trials and an open-air experiment with Pasteurella multocida in rural Australia never took place. Stephen Dando-Collins’ book Pasteur’s Gambit outlines this sordid tale, noting that while there are 30 Pasteur Institutes throughout the world, lingering bitterness and a lengthy Gallic memory insured that none exists in Australia.

Myxomatosis

In 1919, the use of the Myxoma virus (Myxomatosis) for rabbit control in Australia was mooted in correspondence between the Brazilian scientist Henrique de Beaurepaire Aragão and the Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine, Townsville. The scientist was aware that the virus was spread by insect bite and considered that it might be useful in controlling the well-known runaway rabbit population in Australia. As Dr Frank Fenner reports in his definitive study on Myxomatosis, Australia’s Institute of Science and Industry responded, ‘the trade in rabbits both fresh and frozen, either for local food or export, has grown to be one of great importance and popular sentiment here is opposed to the extermination of the rabbit by the use of some virulent organism’.5 As with Pasteur’s earlier proposals, the 20th century rabbit industry once again defended its rural interests.

When the use of Myxomatosis was raised again by a campaign led by Melbourne paediatrician Dr Jean Macnamara in the late 1930s, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) sought permission to bring quantities of the virus into the country. This was granted but under the strictest conditions of quarantine. But once again, the rabbit industry hindered experiments with the rabbit virus by denying land for field trials, but the re-named CSIRO was finally granted a field trial site in South Australia.6

Deliberate spread of Myxomatosis was made illegal in Britain in 1954. Nevertheless, the disease spread all over the country. . . . I also visited scientists involved with Myxomatosis in France, where the Lausanne strain was initially introduced by Dr P. F. Armand Delille by inoculating two wild rabbits on his estate at Maillebois on 14 June 1952, whence it spread all over Europe.

Frank Fenner. Nature, Nurture and Chance. The Lives of Frank and Charles Fenner. 2006. http://press.anu.edu.au/titles/nature-nurture-and-chance/. 14 June 2014.

Finally, in December 1950, following extensive trials and research, the Myxomatosis virus was released in the Murray River valley near Albury NSW. Between 1951–1955, the virus was released in a number of locations in NSW, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. By 1954, the virus was considered endemic in the European rabbit population in Australia.7

Due to an outbreak of Murray Valley encephalitis in February 1951 (in Shepparton and Mildura) paralleling the introduction of Myxomatosis in the region, there was a great deal of public concern the two diseases were somehow related. Following considerable outcry in the press, the CSIRO responded with confidence these two diseases were in no way associated. After a boisterous challenge by the Chair of the Mildura Hospital Board, suggesting that if the virus was harmless, CSIRO staff should expose themselves to it, the Federal Minister in charge of the CSIRO announced in March 1951 that three scientists, Sir Macfarlane Burnet, Sir Ian Clunies Ross (the chair of the CSIRO) and the virologist Dr Frank Fenner, had inoculated themselves with Myxomatosis in 1950, with no effects.8 This silenced the debate.

The role of the rabbit in the rural economy remained important in the early 1950s, but the states took part in the dissemination of Myxomatosis in their rabbit population with the exception of Tasmania, where the State Parliament passed legislation against the introduction of the virus.9 Ignoring Tasmanian law, the virus soon appeared in the state’s rabbit population. With the disease spreading in the island, Tasmania reversed its law and agreed to the release of infected rabbits from the mainland in 1952.

European rabbit with Myxomatosis, Wales, 2013. Photograph by Fletch 2002, Cornish National Liberation Army. Wikimedia Commons

The overt symptoms of Myxomatosis are visually repugnant, unlike the immediate effects of Pasteur’s Pasteurella multocida, which are commonly restricted to the internal organs. Myxomatosis-affected rabbits become listless, their ears droop and their external orifices swell and ooze milky secretions; in the acute stage, nodules (myxomas) and lesions can appear. Facial distortions can also occur leading to blindness and inability to eat or drink. While the disease’s progress is variable, death can take two weeks.

The publicity attending the release of Myxomatosis and the distressing appearance of infected rabbits in the wild brought a dramatic end to professional trapping of rabbits for their fur, skin and carcasses in the 1950s and Australia’s European rabbit export trade collapsed within 12 to 18 months. Rabbit skin exports in 1951 were 122,603 cwt. (cwt. = 112 pounds/50 kilograms] but the export figure fell to 6305 cwt by 1953. Some authorities cite figures that suggest that the rabbit industry rebounded within a few years of the virus’s introduction but these recoveries are not reflected in export figures.10

Calicivirus

The next introduced biological agent, the rabbit calicivirus disease (described by the CSIRO as RCD, currently known as rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus or RHDV) was introduced in a 1995 CSIRO field trial in South Australia but evaded the quarantine and has since spread (by design or by accident) across the nation. An official managed release of RCD began in 1996. The CSIRO began to experiment with the development of the virus in 1991 to offset the decline of the effectiveness of Myxomatosis through natural selection.11 Known to the scientific community as rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (Caliciviridae family), it is also found in China and has now spread to the European rabbit population.

A Field Agent, Emmanuel Hatzi, who is located at Broken Hill . . . takes rabbits from 20–25 specialist rabbit shooters in a normal season. In 1995, Mr Hatzi paid $2.00–2.60 per pair for large rabbits, $1.50-$1.60 for medium rabbits and $1.00 per pair for rabbit kittens.

M. Foster and R. Telford. Structure of the Australian Rabbit Industry: A Preliminary Analysis, ABARE report prepared for the Livestock and Pastoral Division, Department of Primary Industries and Energy, Canberra, 1996, p.14.

Unlike Myxomatosis, the RCD microorganism attacks the internal organs and death occurs within one to three days from initial infection. External visual symptoms or signs are uncommon although paralysis and/or overt restless and agitation can occur. As the virus is a relatively new biological control agent, its ultimate effects on the informal rabbit industry represented by those remaining rabbit hunters and trappers are relatively unknown in 2015. In the mid-1990s, a $9 million domestic market trade in rabbits was recorded.12 The market for wild rabbit skins and carcasses has never fully recovered from the introduction of Myxomatosis and the rabbit calicivirus disease certainly damaged the domestic rabbit trade.

In 1995, the Akubra factory in Kempsey, NSW processed 65,000 local skins a week but facing the calicivirus outbreak, they placed advance orders for British rabbit skins. But at the same time, rabbiters supplying the South Australian market in rabbit carcasses and skins claimed kills of 450 rabbits per night. Clinton Degerhardt, working south of Broken Hill NSW told the Sydney Morning Herald in 1995 he shot so many rabbits in a single night that his utility bed was filled. Degerhardt claimed he was forced to stack rabbit carcasses on the vehicle bonnet to get his kill to the station cool-room.13

Rabbit shooting has also been revived in some regions with reports of 100–150 pairs shot per night, depending on the size of the regional rabbit population. This has rejuvenated elements of the traditional rabbit industry, with rabbit buyers working the rural areas, siting chiller units for carcasses and on-selling to meat and fur processors. Pet food processors also make up a portion of the carcass market. Of course, some rabbiters sell directly to processors when they are accessible.14 Foster and Telford report that rabbiting is more common in the arid areas of Central Australia where the viral agents are less effective but there are active rabbiters in New South Wales and Victoria.15

In the early decades of the 21st century, it would seem that a significant amount of the Australian rabbit meat, hides and fur are derived from domestic rabbit farming. Rabbit farming is now permitted in all states with the exception of Queensland and the Northern Territory and in 2007, $2.5 million of rabbit production was recorded.16 But clearly, the ability of the rabbit population to adapt to biological agents has led to a return of the animal in some areas with a corresponding rise in shooting.