Long-term economic growth in the United States has been slowing for decades. Robert Gordon, I noted in chapter 1, has argued that the period of rapid U.S. growth, from 1920 to 1970, was a golden age never to be revisited. Several economists have joined Gordon in arguing that we have entered an age of secular stagnation. This kind of fatalism is misplaced. The United States, and the world, can achieve rapid economic progress in the coming decades, but only if we address the root causes of slower growth.

First, let’s do some statistical housekeeping. One year’s GDP growth doesn’t tell us too much. GDP data are regularly revised, so that a few quarters of slow growth could be a mere aberration of the data. Even if it’s real, one slow year might signify little when growth is averaged over several years. And GDP growth itself is a deeply flawed measure of wellbeing. High growth does not guarantee shared economic improvement, and slow growth does not necessarily imply widespread economic hardship. In recent decades, most of the fruits of U.S. growth have gone to the richest of the rich, who least need them.

Still, even after accounting for data errors, short-term cycles, and the yawning gaps between GDP and wellbeing, there is little doubt that the U.S. economy is failing to raise living standards at the same pace as in the past. Annual growth of GDP averaged 3.4 percent per year between 1980 and 2000, but only half of that, 1.7 percent per year, between 2000 and 2014. Since the United States is a high-income country, slow growth is not necessarily a catastrophe (compared, say, with extreme poverty, war, or environmental degradation), yet the U.S. economy has room for major improvement.

The big mistake of “secular stagnationists” is to treat the slowdown of U.S. growth as inevitable, a consequence of the drying up of technological opportunities for future economic improvement. Such fatalism is misguided. Long-term economic improvement occurs when societies invest adequately in their future. The harsh fact is that the United States has stopped investing adequately in the future; slow U.S. economic growth is the predictable and regrettable result.

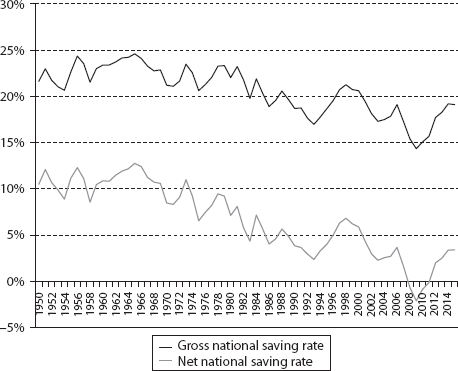

Although simple measures of national saving are flawed, they convey useful information. The evidence suggests that the U.S. national saving rate has declined markedly since the “Golden Age” celebrated by Gordon. The saving rate is measured in two ways: as “gross saving” before subtracting capital depreciation, or as “net saving” after subtracting depreciation, both relative to national income. The net saving rate has declined more than the gross saving rate because capital depreciation as a share of national income has risen in recent decades (see figure 2.1).

FIGURE 2.1 Gross and Net National Saving Rate (percent of GDP)

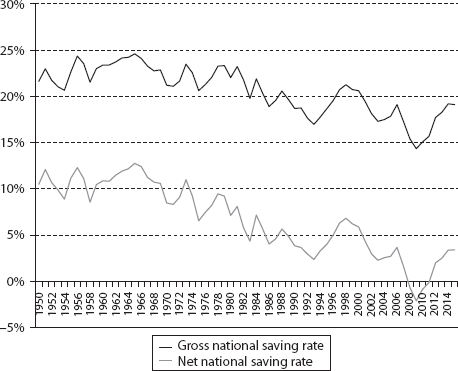

We should also examine separately the net saving rates of the private economy (business and households) and government. We find that both private and government saving rates have declined by roughly the same amount, each by roughly 5 percentage points of national income. Households are not saving as much of their income as they did decades ago. Government (combining federal, state, and local levels) has gone from a net saving rate near zero to a chronic negative net saving rate (see figure 2.2).

FIGURE 2.2 Government and Private Net Saving Rate (percent of GDP)

There are several possible causes. Depreciation of capital is certainly absorbing more of gross saving, as we would expect in a capital-rich, mature economy. Households are aging. And government has turned populist, promising tax cuts at every election cycle, thereby denying the government the revenues needed to provide public services, social insurance, and public investments in America’s future.

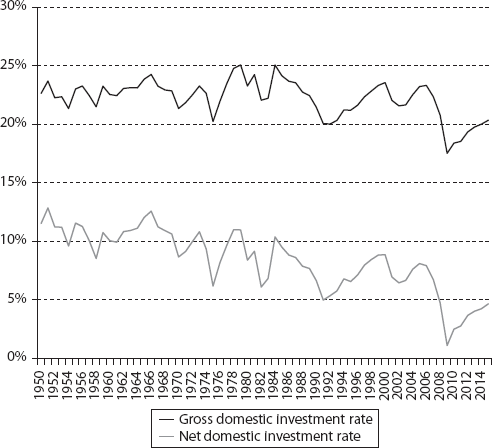

The share of domestic investment in GDP has declined alongside the decline in national saving, though by slightly less as America has borrowed from the rest of the world to offset part of the decline in saving. Figure 2.3 shows both the gross investment rate and the net investment rate, both as a share of GDP, where net investment equals gross investment minus depreciation. Gross investment as a share of GDP has declined by around 3 percentage points since the 1960s. Net investment has declined by even more, around 5 percentage points, as depreciation relative to GDP has increased. The clear message is that both net saving and investment have declined markedly as a share of GDP, contributing significantly to the decline in long-term growth.

FIGURE 2.3 Gross and Net Domestic Investment (as a share of GDP)

With higher saving and investment rates, both public and private, directed towards productive capital, the United States could overcome secular stagnation. The benefits of new scientific and technological breakthroughs—in genomics, nanotechnology, computation, robotics, renewable energy, and more—are certainly within grasp, but only if we invest in their development and uptake. It is especially shocking that at a time when we need new clean energy sources, more nutritious foods, better educational strategies, and smarter cities, we have been cutting the share of national income that government devotes to investments in basic and applied sciences.

In the 1960s, around 4 percent of the federal budget was spent on nondefense research and development (R&D). Now only around 1.5 percent of the budget goes for civilian R&D. As a share of GDP, total federal R&D declined from around 1.23 percent in 1967 to just 0.77 percent in 2015 (see figure 2.4). In the pursuit of tax cuts, we have undermined our collective ability to build a more prosperous and sustainable future. And we’ve done it with little recognition of the long-term consequences.

FIGURE 2.4 Federal Civilian R&D as a Share of National Income, 1976–2015

We certainly notice the crumbling of the roads, bridges, and dams that suffer from chronic undersaving and underinvestment. We are less aware of the science, skills, and natural capital that we are shortchanging as well. And we are less aware still that investing in our future requires robust rates of public and private saving. Golden ages don’t just happen; they reflect societies that choose to save and invest vigorously in their long-term wellbeing.

To restore growth, therefore, we need to restore investment spending. And to restore investment spending, we will need three things. First, the government should raise tax revenues to fund greater public investments. Yes, it is true that some public investments can and should be debt financed, but in view of the prospects of rising budget deficits in future years, described in the next chapter, it will also be necessary to raise government revenues to pay for part of the new public investments.

Second, the government will need to restore its capacity to plan complex public investments. In recent years, nearly every major infrastructure project has become tied up in regulatory knots and public controversy. Often there is no long-term strategy, but only short-term deal making that drains the confidence of the public. In the days of the national highway program (from the mid-1950s to mid-1970s) and the moonshot (during the 1960s), the public had the sense that the federal government had a plan and a strategy to achieve it.

Third, and perhaps most crucially, we need financial system reform, to shift Wall Street from high-frequency trading and hedge fund insider trading back to long-term capital formation. We remember J. P. Morgan as a titan of finance not for shaving a nanosecond from high-frequency stock market trades, but because his banking firm financed much of America’s new industrial economy of the early twentieth century, including steel, railroads, industrial machinery, consumer appliances, and the newly emergent telephone system. U.S. Steel, AT&T, General Electric, International Harvester, and much of the rail industry all bear his financial imprint. If Wall Street continues as a hodgepodge of insider trading, hedge funds, and other wealth management, it will be overtaken by index funds requiring little more than a computer program to operate.

Wall Street’s true future vocation should be to underwrite the new age of sustainable investments in renewable energy, smart grids, self-driving electric vehicles, the Internet of Things (connecting smart machines in integrated urban systems), high-speed rail, broadband-connected schools and hospitals, and other strategic investments of the new era. Wall Street needs the expertise of systems designers, civil engineers, and project managers much more than applied mathematicians cranking out formulas for pricing new derivatives. The financial industry, which created so much mayhem and destruction in the past decade, would once again return to its core vocation of directing the long-term savings of pension and insurance funds into the long-term investments needed for a revival of long-term growth.