This cause of rejoicing must have been short-lived. But letter after letter, during these months, show that the storm-tossed Queen felt at last in port. <c I am altogether satisfied with my son," she repeated in November, "and I think that God wishes to give me some happiness again in this world, finding myself with my family, who do what they can to give it to me." And once more, at Christmas time, " I am the most satisfied person in the world with regard to my daughter-in-law. She is a saint — she is altogether devote. I am very happy with her." That she was also at peace with her second son may be inferred from her mention of " ma fille, la Duchesse de York " ; and

I

LIFE IN ENGLAND 543

Lady Derby, writing of the court during the autumn, describes the Queen as never having been gayer or more happy. Henrietta tells of ballets to be given, and of Charles' desire that she should be present. c< Je crois," she says, <c que j' auray aller."

Giving an account to his sister of his efforts to organise the masque in which he desired that his mother should take a part, the King confessed that they had resulted in failure, owing to the impossibility of finding a man capable of making a proper entree. Catharine was, however, taking kindly to the pastime. " My wife," he added, " has made a good beginning in this way, for the other day she had contre-danses performed in her bedchamber by my Lord Aubigny," her grand almoner, " and two others of her chaplains/'

Altogether, the impression is left upon the mind that, for the present, the " reine malheureuse " had lost her right to the name. It is true that, by Pere Cyprian's account, her health had suffered from the first from the climate of England, of which the Capuchin had but a bad opinion ; but her letters during the year following her return give no sign of permanent illness, and writing in November, 1663, to her sister, who had heard a report that she was to pay one of her accustomed visits to the Bourbon springs, she altogether disclaimed any such intention. She had, she declared, never thought of doing so, and hoped to stand in no need of the cure.

She seems to have established herself, as if for a permanency, in her son's kingdom. Her income was settled, and her household arranged on a footing corresponding to her position, with all its officers, ecclesiastical and secular, St. Albans as before occupying the chief place. The report of the Queen's marriage to her principal servant had gained currency, and is more than

once mentioned by Pepys — " how true God knows," adds, however, the gossip.

As was inevitable, Henrietta was not without her unfavourable critics. The magnificence of her court was viewed with jealousy, and it was observed that it was more frequented than that of her daughter-in-law, where there was " no allowance of laughing and mirth that is at the other's." She was reported to have exceeded her income and run into debt. That she was lavish and open-handed is undoubtedly true ; but her carefulness in regulating her expenditure does not bear out the charge, and her principles as to payment of debts are said to have been exceptionally strong. Thus, when a guest was once extolling the practice of sending alms to distant lands, the Queen, wishing to read a lesson to the speaker, whilst concurring in praise of the charities in question, added that debts must first be paid ; otherwise God rejects and curses the gift. An English memoir published shortly after her death also states that, settled at Somerset House, " she had a large reputation for her justice to all people, paying exactly well for whatsoever her occasions required, weekly discharging all accounts, and withal bestowing good sums of money quarterly to charitable uses."

A curious story belonging to this time finds a place in the same pamphlet, worth quoting as an example of the reports current even amongst those favourably disposed towards the Queen. " She desired," says the writer, u to live with the least offence imaginable to any sort of men, and therefore was very much troubled to hear that of Dr. Dumoulin, prebend of Canterbury . . . her confessor was seen on horseback, brandishing his sword, and to fling his hat by the scaffold where the late King was beheaded ; and being asked why he of

HOSTILITY TOWARDS CATHOLICS 545

all men should do so, replied, That that was the most glorious day that ever came, and that that act was the greatest thing that ever was done to advance the Catholic religion, whose greatest enemy was that day cut off."

Whether the Queen's confessor had been overtaken by a sudden access of madness, or Dr. Dumoulin of Canterbury had dreamt a dream, or the tale was merely invented to increase the odium attaching to Catholics, must remain undetermined. The hostility of Parliament towards their religion needed no strengthening ; and however reluctant Charles may have been to proceed against those belonging to the unpopular faith, he found himself unable to resist the demand for an act of uniformity bearing equally hard upon Catholics and Presbyterians. In April, 1663, it was further necessary to satisfy public sentiment by the issue of a proclamation ordering all priests and Jesuits, save those permitted by the marriage contracts of the two Queens, to leave the kingdom. It does not appear that Henrietta took any active part in opposition to measures so distasteful. She had probably learnt the unwisdom of interference, and the knowledge that Charles was no willing agent in the matter may have helped her to resignation. His efforts to mitigate the severity of religious tests had, indeed, raised so bitter an opposition that he had no choice but to give way.

For the ecclesiastical posts attached to Henrietta's household there had been at first a spirited competition between the Oratorians, supported by St. Albans and Montagu, her almoner, and the Capuchins, who, originally entrusted with the charge of her chapel, had returned to claim their rights. But the Queen had succeeded in composing their differences, and the Capuchins remained in peaceful possession.

against the Catholics, Henrietta's old antagonist, Clarendon, had taken, as might have been expected, a leading part—one which, it is said, was never forgiven by his master. At the same time, when an attempt was made in the summer by his old friend the Earl of Bristol, now reconciled to the Catholic Church, to oust the Chancellor from place and power, Charles was roused to unusual activity on his behalf; whilst the French ambassador, de Comminges, expressing his amazement at the attack made upon a man in Clarendon's position, mentions twice over, amongst the defences which safeguarded him, the support and goodwill of the Queen-Mother. So far, it is therefore evident, Henrietta had remained faithful to the pledge of friendship she had given him.

Meantime, affairs in the royal household were on no better a footing. In the autumn of 1663 it had appeared likely that the neglected Queen was about to escape from her difficulties by betaking herself elsewhere, and a dangerous illness had threatened her life. In her delirium, her preoccupying anxiety found vent, and she raved of the little son she believed herself to have borne, lamenting that her boy was but an ugly boy, but taking comfort when the King, standing by, assured her that he was a very pretty one. c< Nay," she said, c< if it be like you, it is a fine boy indeed, and I would be very well pleased with it." Few in England, save the Queen-Mother, would have grieved had the childless Queen gone to her rest. Charles was soft-hearted, and his tears, according to Waller, contributed to his wife's recovery. But speculation was already rife as to whether the new object of his devotion, Frances Stewart, would occupy the place the Queen would leave vacant.

DEATH OF MADAME ROYALE 547

Human nature is many-sided, and there is no reason to doubt that Charles' tears when he thought his wife was upon her death-bed, mingled as they must have been with remorse and shame, were sincere. Even when she had done him so ill a turn as to recover, the effects of his compunction were visible, and in December he was not only concerning himself with her amusement, reporting to his sister that she had been well enough to be present at a little ball given in the private apartments, but was also begging Madame to send him from France a gift to her liking in the shape of religious prints to place between the leaves of her prayer-book. " She will look at them often enough," he added, enumerating the offices his wife daily said. It was well that Catharine found comfort in her religion, for she must have had little of other kinds. But so long as Henrietta was at hand, her unfortunate daughter-in-law will at least have been sure of one firm friend.

A fresh sorrow was to overtake the Queen-Mother before the close of the year. Her attachment for her sister, the Duchess of Savoy, had continued strong and faithful through the long years of separation; but the tie was now to be broken. With the last days of the year Madame Royale, as she was called in the land of her birth, passed away. The children of Henri of Navarre and Marie de Medicis were a shortlived race, and by the Duchess's death Henrietta was left the sole survivor of the group.

Links with the past were becoming ominously few; but the future lay hopefully before the Queen's sanguine eyes. The little Duke of Cambridge, whose approaching birth had caused the Duke of York to avow his marriage in 1660, was dead, but other children had supplied his place ; and writing to her sister at a time when

HENRIETTA MARIA

she indulged hopes of a direct heir to the throne, the Queen-Mother had boasted that the house of Stuart was not likely to become extinct. It was fortunate that its future destinies were hidden from her sight, and that none of the soothsayers in whom she had displayed a lingering faith had power to withdraw the veil that covered the future, and to show her the lawful heirs driven from their heritage, and become again, to use her own words, vagabonds; whilst strangers and foreigners, with scarcely a drop of the old royal blood running in their veins, sat on the throne of their fathers. With James' children coming fast, with Madame's nursery filling, and with her daughter Mary's little son growing up, there may have seemed—leaving the chance of possible direct heirs to the King out of the reckoning —little fear of the race dying out.

During the year 1664 war with Holland was becoming more and more imminent, whilst relations with France were strained. The sale of Dunkirk had been too bitterly resented by the nation to be easily forgotten, and in allusion to the share he had had in the transaction the Chancellor's new house was nicknamed by the mob the New Dunkirk. When the Houses met in March, Bristol was back in England, and was believed to be again attempting to compass Clarendon's downfall. The King, however, still showed himself the friend of the unpopular minister, and " ran up and down to and from the Chancellor's like a boy." Clarendon's ruin was postponed.

One would imagine that Henrietta, in the course of her present visit to England, must more than once have regretted her choice of those she had brought in her train from Paris. The beautiful Frances Stewart, daughter of Lord Blantyre, who, resisting Louis' efforts to detain her in France, had followed the Queen to England, was

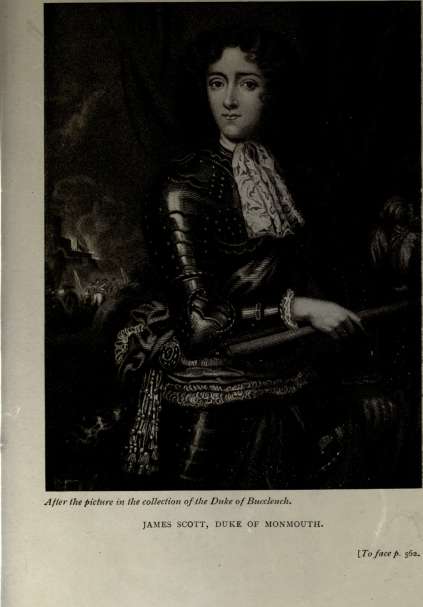

contesting with Lady Castlemaine her place in the King's affections ; and if the responsibility of having introduced Monmouth into the country rested with her, she must also have doubted her wisdom in assuming it. Charles' " extraordinary fondness " for the boy had produced whispers of possible complications in the future ; and the scene at Windsor when the King, entering the ballroom and finding the little Duke dancing bareheaded with the Queen, had kissed him and bidden him put on his hat, would have gone far to give colour to such misgivings. In the autumn of 1664 two members of Henrietta's own household, Madame de Fiennes, a lady of mature years and much indiscretion, and her husband, the Comte de Chapelles, were the chief actors in a scene causing no small disturbance. The Count was the son of Henrietta's nurse ; and in bestowing her hand upon him his wife had been guilty of a mesalliance turned by Mademoiselle into bitter ridicule in days before she contemplated a like sacrifice of sense to sentiment, Her condemnation of the woman who, at forty, and the daughter of an old house, had made herself the daughter-in-law of Madame la Nourrice, sister-in-law of all the maid-servants, and the wife of a young man of two-and-twenty, was not unjustified ; and that Mademoiselle's opinion was in some degree shared by the lady herself is to be assumed from the fact that she never consented to bear her husband's name.

Occupying the post of lady-in-waiting to Henrietta in Paris, and gifted with a sharp tongue, a caustic wit, and an arrogant temper, she had made an embittered enemy of Anne of Austria, and was probably glad to accompany Henrietta to England, where her husband obtained a post in the Queen's Guards at Somerset House, of which St. Albans was captain.

It was between the Count and his superior officer that a quarrel took place in the very ante-chamber of the Queen. Having by some show of insubordination given offence to St. Albans, the latter addressed him after an abusive fashion, adding that, had he not been restrained by respect for the royal precincts, he would have run the Count through the body. Chapelles resented the menace with his hand on his sword, and those present were obliged to throw themselves between the disputants to part them.

Henrietta, informed of the quarrel, interposed at this point in person, pardoned the outrage to herself, and directed Chapelles to make proper apology to the earl. All might have been thus composed, had not a new element been introduced by the arrival upon the scene of Madame de Fiennes, who, apparently beside herself with anger, reproached the Queen with services done her by Chapelles, and went so far as to tell her mistress that it was to his mother that she owed her life. The very extravagance of her passion probably prevented Henrietta from taking the matter seriously, and though the laugh with which she received the attack only kindled the angry woman's wrath the more, the affair ended without serious consequences, and is chiefly worth notice as corroborating other accounts of the Queen's indulgence towards her servants. Chapelles was reported by the King to his sister to have been " as much in the wrong as a man could well be to his superior officer " ; but even when that officer was St. Albans, Henrietta was ready to forgive the offence. De Comminges, it is true, noted that, though " bonne jusqu'a 1'exces," she was not pleased, and that this last outbreak of her lady-in-waiting had revived the memory of numberless small offences in the past; whilst her vexation had been increased by the fact that

THE FRENCH AMBASSADORS

the King—suspected of anti-French proclivities—had been delighted at the incident. It might, de Corn-mi nges thought, end in Madame de Fiennes' and her husband's return to France. Such was not, however, the result. The extreme kindness of the Queen had, the envoy reported, imposed silence upon all with regard to what had passed, and it was not until Henrietta left England that Madame de Fiennes likewise crossed the Channel.

The tendency shared by King and nation to rejoice at whatever might redound to the discredit of France must have been a serious cause of trouble to the French Queen. For her part, she had done what she could to atone, by special courtesy, for the lack of cordiality displayed towards the representatives of the Roi Soleil, come to England with a view to promote a good understanding between the two countries, and to keep peace, if possible, between England and Louis' own ally, Holland. " I had an audience of the Queen-Mother," wrote de Comminges on his first arrival, " who, to oblige the King [Louis], wished that my coaches might be allowed in the yard ; and I must confess that I was received by all the officers with so much honour and such a show of satisfaction that nothing could be added to it." When the ambassadors had been treated with deliberate incivility by Clarendon and others at a banquet of the Lord Mayor's, and the affair had been too serious to be passed lightly over, St. Albans and Montagu were amongst the first to repair to the embassy with the object of preserving peace. It was, however, difficult, when the whole nation was hostile, to avoid collisions; and de Comminges, later on, mentions, as an example of the absurdity of the reports which gained easy credence, that when he had presented Henrietta with a caleche sent her by King

HENRIETTA MARIA

Louis, half the town had run to inspect it, saying that it represented the tribute paid by France to England ; and that, to conceal the obligation, the King had permitted that it should be offered to his mother.

England was soon to realise that Louis was not paying tribute to Charles. In the meantime, negotiations proceeded slowly ; and Henrietta will have looked on anxiously at the efforts of the envoys—with whom a half-brother of her own, the Due de Verneuil, was associated—to place matters on a satisfactory footing. A scene is described when, in the middle of an inconclusive interview between the ambassadors and the King, a door was thrown open and the Queen-Mother, in retiring, passed through the room, saying, as she went by, the words, " Dieu vous benisse," understood by the Frenchmen to contain an expression of her hopes for their success. By the spring of 1665 it was plain that those hopes would not be fulfilled, and in April war was formally declared with Holland. At first victory lay with the English, and James was the hero of the hour. But by the time that news of his successes reached London it was in a condition making it difficult to rejoice. The plague was come.

Whether the epidemic had a share in deciding Henrietta to pay a visit to France does not appear. Independently of it, there was no lack of cause for her to leave England for a time. Long before she had contemplated the step, the French ambassador, in a letter to his master, had predicted that she would be forced to take it. She had, de Comminges said, grown very thin, and had a consumptive cough. Her doctor told her that he could not answer for her life if she remained in England, and all her household were of the same opinion. The envoy's letter had been written

THE QUEEN GOES TO FRANCE 553

before she had been in London six months. It was now close upon three years since she had left France. Her health was failing more and more, and her thoughts were turning towards the waters of Bourbon, always efficacious in the past. One consideration alone deterred her from trying the cure. This was the fear lest, her presence removed, the interests of the Catholics who had gathered round her chapel should suffer. If it were to be closed for a single day in consequence of her absence, she would, she told Charles, renounce the idea of seeking a remedy abroad, and would stay in London, live as long as it pleased God, and then die. It was only when the King gave her the required assurance that her chapel should remain open, and the Capuchins at liberty to continue their ministrations, that she determined to seek relief from her ailments in her native air.

By the end of June her preparations for departure had been made, and Pepys, calling at Somerset House on the 29th, found all packing up, and heard that the Queen was to start for France that day, "she being in a consumption, and intended not to come home till winter come twelve-months."

Before leaving London she called together the monks in charge of the chapel, and gave them their directions. By God's grace, she said, she hoped her absence would not be long. The chapel was to remain open, and she charged them to do their duty by those who resorted to it. After which she quitted London for the last time, and started on her journey, accompanied by the King, Queen, and court as far as the Nore, and by the Duke of York to Calais. When she separated from him there and proceeded on her way, she had taken final leave of her two remaining sons.

CHAPTER XXVII

1665 — 1669

Latter years—Detachment from life—Madame's health —Influence on politics—Louis at Colombes—Henrietta remains in France—England and France—Henrietta's intervention—Clarendon's disgrace — Monmouth—Last days—Death and burial.

FOUR years of life remained to the Queen. They were years of which comparatively little is to be related. As a factor of importance in politics she had long ceased to exist ; and if she had hitherto retained her place as a social figure in the public view, this modified form of notoriety was in great part to end. At times, it is true, she emerges from the obscurity, and shows herself once again exercising an influence upon the relations between the country of her adoption and that of her birth ; but such occasions only break in, as it were, upon a life of seclusion. For the most part she remained behind the scenes. The memoir-writers of the day had little attention to spare for a queen whose life was in large measure that of a recluse ; and the glimpses of her which it is possible to obtain are chiefly supplied by the records of men and women who knew and loved her, and were in some sort associated with her vie intime: the faithful old Capuchin who had accompanied her in her wanderings ; Madame de Motteville, her friend ; and the biographer who drew his materials from the nuns who had been the companions of her solitude at Chaillot.

Taking a general survey of these latter years, the impression conveyed is that, in spite of failing health and physical suffering—in spite, too, of the anxiety and sorrow which must have been caused by the troubled course of the domestic affairs of her " other little self," Madame—they were not unhappy. If the world was becoming forgetful of the Queen, she for her part was leaving the world behind her. The inner and religious life which, in spite of mundane ambitions, vanities, and trivialities, had always maintained a genuine existence, was gradually asserting its supremacy. Nor is there any record of quarrels, rivalries, or intrigues belonging to this period. If hers had been a day of storm and tempest, partly the result of circumstances, partly of her own unwisdom, the evening was closing in serenely, and the sun, setting in tranquillity and peace, was illuminating the darkness of past days. Looking backward, she had learnt to be grateful for her sorrows ; and in the seclusion of Chaillot, where much of her time was passed, she was often heard to say that for two things she gave thanks to God daily —that He had made her a Christian, and that she had been "la reine malheureuse." The title she had claimed in the bitterness of her sorrow she now accepted as a grace. u Her griefs," said Bossuet, in his funeral oration, " had made her learned in the science of salvation and the efficacy of the cross."

Of any other learning, even connected with religion, she had probably little. It was her daily custom to read part of the Imitation of Christ, beginning the book afresh when the end was reached ; and so constant had been her study of it that she had much of the text by heart. But on theological problems or the controversies of the day her interest had never been great. It is related that when two bishops were on one occasion

HENRIETTA MARIA

discussing in her presence the new doctrines concerning grace then agitating men's minds, she listened for a time to their arguments, whilst each strove to instruct her in the views to which he inclined ; then . asked, with a simplicity one imagines to have been partly assumed, whether the new tenets taught easier methods of acquiring holiness, adding—the answer being mani-festedly drawn from A Kempis—that she loved better to labour at acquiring it than to know how it should be defined. When not prelates, but a feminine theologian, discussed the same controverted theme, the Queen heard her with courteous attention, praised the " vivacite de son esprit," and passed on to other subjects of conversation.

As time went by, those who watched her noted a detachment from life the more remarkable in a nature that, apart from the motive power of religion, would have seemed made to cling to things material. When the end was near at hand, she observed to a nun charged with the duty of attending upon her that it was true that for some time she had felt altogether God's. So, in peace and tranquillity, she awaited what was to come.

It had been gradually and by degrees that, with increasing infirmities, she had let go, as it were, the cords that, on her first arrival in France, bound her to life. There was much in it to interest her, both pleasurably and painfully ; nor was she likely, with her warm heart and strong affections, to seek to withdraw from participation in the sorrows and joys of those she loved. She had been met at once by trouble and anxiety. A false report of the death or disappearance of the Duke of York, after the late naval battle, had given so severe a shock to the Duchess of Orleans

HENRIETTA AS MEDIATRIX 557

that her baby was born dead ; and Henrietta reached Versailles in time to nurse her and watch over her recovery. When this was assured the Queen returned to Colombes until it should be the season to proceed to Bourbon.

Other work besides that of nursing had awaited her in France. It was possibly not on account of her health alone that Charles had been ready to facilitate his mother's visit to her native country. The relations between the two Governments were in a critical condition ; and he may have looked to the Queen, with her credit with the Queen-Mother, to act as mediatrix.

At the French court there was every desire to avoid, if possible, a breach with England ; but taking into account the ct antipathic passionee " existing at the moment between the two nations, it scarcely required the engagement pledging France to render assistance to Holland to make war almost inevitable. Under these circumstances, if peace was to be maintained, no means of promoting it could be neglected, and Madame had been rapidly becoming an important channel of communication between the two Kings. On Henrietta's arrival she was associated with her daughter in conducting these informal negotiations ; and a scene which took place on the very day preceding her departure for Bourbon indicates the importance which attached to the position she occupied.

On that day Henrietta, in her retreat at Colombes, received many visitors. Hollis, the English ambassador at Paris, had come to pay his respects to King Charles' mother. Upon Hollis followed Louis himself ; whilst a third guest was the Prince de Conde. Whether or not the young King was displeased at finding Charles' 1 C. Rousset, Histoire de Louvois.

ambassador in possession of the field, his bearing towards Hollis was distinguished by scant courtesy. The envoy, however, was equal to the occasion, and according to his own report, having received nothing but " a little salute with his head " from Louis, maintained the ambassadorial dignity by replying with a just such another." After which he employed himself, during the remainder of the royal visit, by conversing with Conde, who showed himself very affectionate in all that concerned Charles. " Soon after/' pursues the ambassador, " the King of France and the Queen-Mother went alone into her bedchamber ; and our Princess, Madame, went in after they had been there at least an hour."

It was hard upon the professional diplomatist to be set aside at his own business ; nor was he to be informed what had taken place at the conference. When Louis had brought his visit to an end and had taken leave of his aunt, Hollis ventured to ask the Queen " how she found things ? " Henrietta, who appears to have become versed in the art of speaking without conveying information, answered vaguely that all the talk had been of the Dutch affairs, and that the King had told her that he had made Charles some very fair propositions, and that if they were refused he would have to take part with Holland. When the ambassador further inquired whether she knew what these propositions were, Henrietta answered in the negative; which Hollis considered, though possible, singular. Perhaps, he added, she had not thought fit to acquaint him with them—a not improbable explanation.

Henrietta's hopes of obtaining relief from the Bourbon waters were but imperfectly realised ; and though she derived a certain amount of benefit from them, her health continued unsatisfactory, and she suffered

I

From the picture by Sir Peter Lely.

HENRIETTE, DUCHESS OF ORLEANS.

in especial from sleeplessness. The question of a return to England does not appear to have been mooted. Clarendon suggests that she had all along contemplated a longer absence than her avowed intentions had indicated. She may, on the other hand, have insensibly drifted into making her home in France. At all events, the matter never seems to have so much as come under discussion. Her failing strength would have been reason enough to cause a return to the more northern climate to be indefinitely postponed; and had she seriously taken the matter into consideration, it may be that her presence appeared more necessary to Madame than to her sons on the other side of the Channel. Her three years' residence in London will have taught her the precise amount of influence which, notwithstanding his affection for her, she was able to exert with regard to Charles' domestic arrangements ; whilst the genuine liking for his mother-in-law's society displayed by Monsieur and his confidence in her judgment may have led her to hope that she might prove of use in averting the accentuation of the differences between her favourite child and her husband. She remained in France, passing the winters in Paris at the Hotel de la Baziniere, assigned to her by the King, and retiring in summer to Colombes, with frequent intervals spent at the home of her predilection, Chaillot.

Death was busy in the royal house during the year 1666. Anne of Austria, after a protracted agony, borne with something approaching to heroism, went in January to her rest, a tie which had lasted for Henrietta over some fifty years being thus severed. And before the close of the year Madame's little son, the Due de Valois, was dead ; at which, says the Capuchin chronicler, the Queen grieved very greatly, the more because she knew that his mother could not be comforted.

To personal and domestic sorrows was added, for Henrietta, the formal and reluctant declaration of war, forced from Louis by the terms of his treaty with Holland. Even when this had taken place there was no undue haste in the initiation of active hostilities, and Louis was manifestly ready to renew negotiations with Charles. Henrietta was once more at work upon the endeavour to promote peace, and Clarendon recorded, in 1667, that she had found " another style " at the French court " than the one it had been used to converse in," and that the King showed a desire for pacific relations. St. Albans was sent to London to obtain a commission to treat with Louis ; and though Charles at first demurred at the intermediary, who, according to the Chancellor, " he used always to say was more a French than an English man," a limited authority to carry on negotiations in Paris was at length conferred upon him.

Notwithstanding the position he filled, Madame and her mother remained the chief channels of communication between the two courts ; and secrecy was considered so essential that the letters of each King were sent under cover to Henrietta at Colombes, to be forwarded by her, in envelopes addressed in her handwriting, to their respective destinations. That the secret is said to have been well kept corroborates the assertion that Henrietta had learnt the value of silence, and the confidence placed in her by both Kings bears witness to a discretion she had acquired in later years. It was in her hands that the written pledge embodying the terms of the agreement, signed by both Louis and Charles, was placed for greater security when the private negotiations had terminated successfully.

The furthering of these negotiations must have been

PEACE WITH FRANCE 561

the last public work of importance in which the Queen engaged. Their issue was of the greater moment since, at the very time that they were in progress, England was watching with humiliation the blaze of her own vessels, set on fire by the victorious enemy in the Thames. By the end of July, peace had been concluded between the three belligerents. The disastrous war was at an end.

If Henrietta had a right to rejoice in what was in part the result of her labours, she can have had little attention at this time to spare for the affairs of nations. With women private interests commonly take precedence of public ones ; and anxiety with regard to Madame was pressing upon the Queen. Always delicate, she had been prematurely confined, and her condition had been so serious that for a quarter of an hour she had been believed to be dead. Her mother remained at Saint-Cloud to superintend her slow recovery, and to induce her to forego for a time her habitual amusements. It was, however, no unmitigated form of quiet that the invalid could be brought to tolerate, and as she lay upon her couch the stream of visitors succeeded one another from morning till late at night.

Two events had taken place in London during the course of this year which will have been regarded with special interest by Henrietta. These were the marriage of Frances Stewart with the Duke of Richmond, and the disgrace and dismissal of Clarendon. The rumour that the new-made Duchess, who had by her marriage incurred the hot indignation of the King, was contemplating the application for a post in Henrietta's household, as well as the fact that she kept a " great court " at Somerset House, makes it probable that the Queen had not shrunk from braving her son's displeasure by lending her support

to the woman who had, for the time, severed her connection with him and pursued a line of conduct characterised by Charles in a letter to his sister, as being tc as bad as a breach of faith and friendship could make it." There is also negative proof that Henrietta took no part in precipitating the fall of her old enemy, Clarendon. What evidence is forthcoming points, indeed, in an opposite direction. In a letter replying to remonstrances addressed to him by Madame Charles added that he had written at length to the Queen on the subject of Lord Clarendon, and that he had no doubt that upon this as upon other matters his sister had been greatly misinformed. The inference to be drawn is that his mother, no less than Madame, had taken the Chancellor's part, and we are justified in hoping that she had no pleasure in his undoing, and that old grudges were forgotten.

France was still the school of manners, and in the winter of 1666-7 Charles sent his son, young Monmouth, to make his debut there under his sister's auspices. By her care, the lad, at nineteen, was initiated into life as carried on at the court of the Roi Soleil ; and, according to Mademoiselle, was singled out for special favour by Louis. Between Madame and the Duke a fast friendship was formed, which, innocent as. it was, gave a fresh impulse to Monsieur's jealousy, and resulted in the removal of his wife, in his company and that of his favourite, the Chevalier de Lorraine, to the country retreat of Villers Cotterets, where Henrietta had taken her daughter for change of air during the preceding year. If Madame had then testified no liking for its enforced quiet, she found it yet more unendurable when her retirement was shared by her present companions ; and she must have felt she was paying dearly for the lessons in

After the picture in the collection of the Duke of Buccleuch.

JAMES SCOTT, DUKE OF MONMOUTH

the contre-danse received from her nephew in exchange for her instructions in other arts.

Meantime Henrietta's strength was visibly failing. If she had not refused to take her part in political affairs when it seemed that her interposition might prove of use ; if she was ever ready, in sickness or health, to be at Madame's side when circumstances called for her presence there,—she was gradually learning to realise that the sands of her life were running out.

More and more she withdrew from the world, the habits of the recluse encroaching upon those of the Queen. Whether at Chaillot or without its walls, she was wont to follow, so far as health and the necessary demands upon her time permitted, the rules of the order there established, her attention concentrated to a greater and greater degree upon another world from that in which her part was nearly played out.

If, however, the end was approaching, it was probably by imperceptible degrees. Madame and her mother were too often together for the declining strength of the one to have come with a shock to her daughter, and in Charles' letters to his sister, still employed as intermediary in matters political and the repository ot secrets of which his ministers were ignorant, there is no evidence that the Queen's health was matter of serious anxiety. In March, 1669, after dealing with public affairs, he goes on to jest at his mother's proverbial ill luck at sea. A messenger sent by Madame had suffered, it was supposed, shipwreck. " I hear," added the King, " Mam sent me a present by him, which I believe brought him the ill luck, so as she ought in conscience to be at the charges of praying for his soul, for 'tis her fortune has made the man miscarry."

Nevertheless, when in April another little daughter VOL. n. 17

was added to the Orleans nursery, the fact that her mother was not strong enough to be with the Duchess points to a step downwards. She had been seriously ill in the winter, and, though she had recovered, she would tell those about her that she saw well that she must think of her departure. If she feared death, as Madame de Motteville says was the case, she did not shrink from facing it; and during her last visit to Chaillot she had, as if with a presentiment of the coming end, written out a species of will.

Her headquarters continued to be at Colombes, and it was there that the summer and autumn of 1669 were to be spent. But she intended to pass the Feast of All Saints at Chaillot, and, as one biographer states, to make her home there permanently for the future.

It was at her country home, however, that the end came. Built near the river, some two leagues from Paris, with nothing of grandeur or pretension about the house or gardens, Colombes was a pleasant and quiet place wherein to pass the summer days ; but, as they went by, Henrietta's strength was failing. Her old trouble of sleeplessness was gaining upon her, nor does it seem that she contemplated further trial of the Bourbon waters. There is a point where it is tacitly agreed that remedies are vain. " The last time that I had the honour of seeing her," wrote Madame de Motteville, " she told Mademoiselle Testu and myself that she was going to establish herself at Chaillot, to die there ; that she would think no more of doctors or physic, but only of her salvation.'*

The presentiment of coming death did not cloud or sadden her mind. Up to the last Pere Cyprian records that her conversation kept its gaiety and wit, brightening

all around her. She retained the gift of charming those with whom she was brought into contact. In earlier days it is said that the nuns at Chaillot found so much pleasure in talking to her that ( their simplicity was suffering,' and the Mother begged her to permit them to take their recreation apart. Madame de Motteville also dwells upon the familiarity she used, though without losing her royal air, with her friends. " She loved truth, loved to speak it and to hear it." Such qualities are specially winning in a queen, and if Henrietta had had her fair share of hate, she had been well loved. But in spite of her courage, those belonging to the inner circle surrounding her must have had their unquiet suspicions that the days of that pleasant intercourse were numbered. In August her symptoms had become serious enough to cause the Duke and Duchess of Orleans to urge a consultation of physicians, King Louis sending his doctor, M. Valot, to take part in it, when the Queen explained her malady so clearly as to leave her own medical attendant nothing to add save the nature of the remedies he had used. M. Valot then gave his opinion. The illness, he told the patient, was painful but not dangerous—proceeding to prescribe a remedy for the sleeplessness with which she was troubled. He would add, for this purpose, three grains to the medicine already administered by her domestic physician.

The mention of " grains " appears at once to have suggested opium to the Queen's mind, and she protested energetically. Her experience was opposed to anything of the kind, and she further quoted a warning she had received in earlier days from Sir Theodore Mayerne, who had cautioned her against the use ot any such drug—citing also, with a laugh, a prophecy hazarded long ago in England that she would die of

a <c grain." She feared, she told the doctors lightly, it would be one of those now to be given her.

M. Valot, though with much respect, declined to be convinced either by the authority of the Queen's old physician, by her conviction, or by the prophecy she had adduced in support of it. The grain to be administered, she was assured, did not contain opium ; it was a medicine of special composition, of which he begged she would make trial.

In the end the Queen gave way. Of the four doctors present, three were in full agreement, and she yielded to their representations.

At supper she was in good spirits, and Pere Cyprian notes, with loving minuteness, that she laughed as if she were feeling well. Going early to bed she fell asleep, and remained sleeping, until the over-conscientious lady-in-waiting, somewhat strangely, roused her at eleven o'clock to administer the prescribed opiate. After this she was never heard to speak again. May erne and her own presentiments were justified. The " grain " had killed her.

At daybreak the lady-in-waiting, who had left her for the night, came to awaken her once more to take a draught prescribed by Valot. Speaking to the Queen and receiving no answer, she became alarmed, and, when all efforts to rouse her mistress had failed, she hastened to summon priests and physicians. "We came first," says Pere Cyprian ; " the doctors soon followed." Doctors and priests questioned her, each after their kind, the first as to her physical condition, the others of sin, of penitence, of the love of God. " We entreated her to make some sign that she heard us." But there was no reply. The doctors believed her to be not only living, but sensible. A dull vapour, mounting to the

brain, they said, prevented speech. This would dissipate and she would show consciousness. They were wrong. The sacrament of extreme unction was administered, and in silence, " with a great sweetness and serenity of countenance/' she passed away.

Accounts of the same event are apt, with no apparent motive, to differ. Pere Cyprian, who must have been intimately acquainted with the facts, and from whose narrative the description of the Queen's last hours has been drawn, should be a good authority. On the other hand, there is no reason to believe that St. Albans, in his report to the King, would have deliberately departed from the truth. Yet his story varies in several particulars from that of the Capuchin. According to his statement, the condition of the Queen, at the hour when the laudanum should have been taken, caused the physicians to decide, at the last moment, against administering it ; and only when, unable to sleep, Henrietta demanded the opiate, did her domestic doctor suffer himself to be overruled, and, against his judgment, yield to her desire. St. Albans goes on to say that, remaining at her side to watch the effects of the drug and becoming alarmed by the profoundness of her slumber, Dr. Duquesne used all endeavours to rouse her, but in vain ; and that between three and four in the morning the end had come.

It is possible that the discrepancy between the two accounts is due to an attempt upon the part of the doctor to shift the responsibility of the fatal measure as far as might be upon the dead, and also to shield himself from the charge of negligence in having failed to watch the effects of the drug. In any case, the matter is of small importance, and is only worth noticing as an instance of the difficulty of reconciling contemporaneous

HENRIETTA MARIA

reports of the same occurrence. The blame for the disaster was very generally laid upon King Louis' doctor, and an epigram of the day pointed out that, whilst both her father and her husband had been murdered, Henrietta had not escaped a similar fate :

Et maintenant meurt Henriette, Par 1'ignorance de Vallot.

Thus died Henrietta Maria de Bourbon, the last surviving child of the great Henri, in the sixty-first year of her age. On the following day her heart was carried by Walter Montagu and the whole of the household to Chaillot. Her body lay at the convent in state until, on September i2th, it was placed at Saint-Denis amongst the kings of France, there to remain until, at the time of the Revolution, it was ejected from its resting-place.

All honour was paid to her memory. In England, little as she had there been loved living, the mourning at her death was deep and prolonged ; and in France her funeral, as well as the subsequent memorial ceremonies, were conducted with due splendour and magnificence. It was at a great service, caused by Henriette-Anne to be performed at Chaillot in the following November, that, in the presence of the daughter who loved her so well, and with the waxen effigy of the dead Queen lying before the altar, Bossuet pronounced his celebrated panegyric upon the Queen, the wife, and the mother.

Such panegyrics, true or false, must necessarily partake more or less of the character of a perfunctory tribute ; and Bossuet's great oration is remembered rather as a triumph of eloquence than as an eulogy of the dead. But Henrietta is not of those who need a showman to exhibit their merits and apologise for their defects. Such

as she was, she displayed herself to the world, natural, spontaneous, with a total absence of pose or pretence, and—like her daughter—very human. On the background of a past of shadows her figure, painted by her own actions and words, stands out, vivid and life-like. In spite of her descent, and notwithstanding the blood of Henri of Navarre, she was cast in no heroic mould. Had a happier destiny been hers she might have passed through life leaving little mark, loving God and man, gay, thoughtless, self-willed, and winning. Grief and disaster printed another stamp upon her, and misfortune called forth a power of resistance, a courage, and a buoyancy which might under other circumstances have rested unsuspected. But the same circumstances caused her blunders to take on the complexion of crimes. Unfitted by nature and training to cope with a crisis of almost unexampled difficulty, she was forced into a position she was unqualified to fill ; and her errors of judgment, whilst almost inevitable, invited the condemnation not only of her enemies, but of those of the King's adherents who suffered for them. The measure dealt out to her by contemporaries was hard; but perhaps posterity has been even more unrelenting. Living, if the meddler in affairs of State, the blundering politician, was hated and reviled, the woman was loved. Dead, the woman has not seldom been forgotten, and the politician alone, with the disastrous consequences of her mistaken statecraft, remembered.

The apologist who should endeavour to justify her public actions would have a difficult task. But in order to apportion with fairness the degree of blame attaching to her unwise endeavours to arrest the tide of revolution, it must be borne in mind that, unlike many who, sharing her responsibility, have incurred a less amount or blame,

HENRIETTA MARIA

she was a foreigner whose period of naturalisation had been wholly passed in the artificial atmosphere of a court ; that any true and serviceable appreciation of the forces arrayed against the English monarchy would, on her part, have come near to a miracle ; and, finally, that she was a woman, spirited and fearless, but with a woman's inapt-ness for a grasp of the broader issues at stake and the general trend of events.

For the rest, a revolution inevitably appears to kings something so out of the common, so abnormal, that they find a difficulty in realising the conditions of the struggle sufficiently to meet it with wisdom. " Helas," says Amiel of the ultimate catastrophe of death, " il n'y a pas d'antecedent pour cela. 11 faut improviser—c'est done si difficile." It is indeed difficult to meet a crisis having no fellow in experience, and the actors called upon to face it may fairly claim the indulgence accorded to an unrehearsed effect. That measure of indulgence should be granted, not only to Charles in his weakness and vacillation, but to Henrietta, striving rashly and with unpractised hands to build a dyke against a deluge.

APPENDIX I HENRIETTA MARIA AND JERMYN

IT was asserted at the time, and has constantly been repeated since, that a secret marriage bond existed between the Queen and the man who filled so many posts in her household. It was a time when such reports, true or false, were apt to gain currency. Anne of Austria has been believed to have been Mazarin's wife, and it was said that the widowed Princess of Orange, Charles I.'s eldest daughter, was married to the younger Henry Jermyri, nephew and heir to her mother's favourite.

With regard to the alleged marriage of Henrietta Maria, the evidence is scanty. The affair was plainly matter of contemporary gossip. It was mentioned to Sir John Reresby by a cousin of his in a convent at Paris, and he adds that, though he was incredulous at the time, it was certainly true. Pepys twice alludes to the report. " This day Mr. Moore told me," he writes, November 22nd, 1662," that for certain the Queen-Mother is married to my Lord St. Albans ;" and again at the end of the same year, " Her being married to my Lord St. Albans is commonly talked of; and that they had a daughter between them in France, how true, God knows." The matter is also mentioned in the Comte de Gramont's Memoirs. But the most circumstantial evidence that has been brought in support of a fact which, so far, rests upon mere rumour, is contained in a footnote added to an early biography in a reprint belonging to the year 1820. It is here stated as " undoubtedly true" that Henrietta Maria was married to the Earl of St. Albans shortly after the King's death. In proof of this assertion it is related that " the late Mr. Coram, the print-seller, purchased of Yardly

APPENDIX I

(a dealer in waste paper and parchment) a deed of settlement of an estate from Henry Jermyn, Earl of St. Albans, to Henrietta Maria, as a marriage dower ; which, besides the signature of the Earl, was subscribed by Cowley, the poet, and other persons as witnesses. Mr. Coram sold the deed to the Rev. Mr. Brand for five guineas, who cut off many of the names on the deed to enrich his collection of autographs. At the sale of this gentleman's effects they passed into the hands of the late Mr. Bindley."

If the tale is circumstantial, it is unsupported by any evidence now available ; and there are one or two details which tend to discredit it. The statement, in particular, that the King's widow married her favourite shortly after Charles' death, and that the deed in question bore his signature as Earl of St. Albans, is disproved by the fact that only immediately before the Restoration and ten years after Charles' execution was Jermyn raised to that rank. The explanation of the mutilation of so valuable a document is also improbable.

It is likewise to be noted that, neither in the letters sent by Lord Hatton from Paris, nor in any of those of Hyde, Nicholas, Ormond, or other persons of weight, adverse as many of them were to the Queen, is any allusion to the marriage to be found. Their silence, it is true, might result from one of two causes. They might have been ignorant of so important a fact, although it was matter of common talk, or respect for their dead master's memory might have kept them silent. In the case of men such as Ormond or Hyde, the latter theory is not untenable. On the other hand, it is difficult to believe that, had the marriage report been supported, if not by actual proof, by a respectable amount of evidence, Hatton, with his inveterate love of gossip, or Nicholas, in his personal dislike and rancour, would have altogether avoided the subject and forborne from allusions to a fact redounding to the Queen's discredit.

One more point should be taken into account in weighing the evidence—evidence of a somewhat negative nature — telling against the probability of the marriage having taken

APPENDIX I

573

place. Henrietta's violent repudiation of the possibility of a marriage between her elder daughter and the Duke of Buckingham, together with her indignation at the Duke of York's union with Anne Hyde, cannot be accepted as disproving a mesalliance of her own. But the consciousness of a secret of the kind, with the likelihood of its coming to light, would surely have tended to moderate her language on these occasions.

It must, however, be admitted that the perpetual coupling by her contemporaries of the Queen's name with that of Jermyn, in all matters of conduct, policy, or opinion, has a cumulative weight which cannot be disregarded ; whilst the letter from Jermyn to Charles II., with reference to the Queen's attempt to convert the Duke of Gloucester, quoted in Chapter XXII., appears to point to some special relationship between himself and Henrietta.

On the whole, it must be repeated that this question is one of those hitherto undetermined by history.

APPENDIX II AUTHORITIES CONSULTED

Letters of Henrietta Maria. Ed. M. A. Everett Green.

Lettres inedites de Henriette Marie. Ed. Le Comte C. de Baillon.

Lettres de Henriette Marie de France a sa S&ur, Christine, Duchesse de Savoie. Ed. Ferrero.

Vie de Henriette Marie de France. C. C. [Carlo Cotolendi.] 1690.

The Lives of the Queens of England. Agnes Strickland.

Henriette Marie. Comte de Baillon.

Frankland's Annals of Charles I. 1681.

Life and Death of Henrietta Maria de Bourbon. 1685. Reprinted by G. Smeeton. 18-20.

Memoirs of Sir Philip Warwick.

Clarendon's History of the Rebellion.

Life of Clarendon.

Stafford's Letters and Despatches. With Life, by Sir G. Radcliffe.

The History of the Thrice Illustrious Princess^ Henrietta Maria de Bourbon. J. Dauncey. 1660.

Court and Times of Charles I.

Commentaries on the Life and Reign of Charles /. B. Disraeli.

Cabala. 1691.

Rushworth's Historical Collections.

Calendars of State Papers in the Record Office.

Clarendon State Papers.

Calendar of Clarendon State Papers in the Bodleian Library.

Collins' Historical Collections.

Collection of Original Papers. Thomas Carte

History of England under Buckingham and Charles I. S. Rawson Gardiner.

Personal Government of Charles I. S. Rawson Gardiner.

APPENDIX II

The Fall of the Monarchy. S. Rawson Gardiner.

History of the Great Civil War. S. Rawson Gardiner.

Macpherson's Original Papers, vol. i.

Sir John Berkeley's Relics.

The Lady of Latham. Life and Letters of the Countess of Derby. Madame H. de Witt.

Letters of Charles I. to Henrietta Maria, 1646. Ed. J. Bruce (Camden Society).

Life of James, Duke of Ormond. Thomas Carte.

Thurloe Papers.

Green's History of the English People.

Howell's Familiar Letters.

Supplement to Sir John Dalrymple's Memoirs.

Lives of the Princesses of England. M. A. Everett Green.

Pepys* Diary.

Appendix to Pepys' Diary.

Supplement to Burners History of His Own Times.

Collection of Royal Letters. Sir G. Bromley.

Evelyn's Diary and Correspondence.

Memoirs of Prince Rupert and the Cavaliers. E. B. G. Warburton.

Memoir of Gregorio Panzani, giving an account of his agency in England. Tr. J. Berington.

Life of Strafford. John Forstcr.

Life of Sir John Eliot. John Forster.

Memoirs of the Embassy of the Marshal de Bassompierre to England. Tr., with notes, by J. W. Croker.

Memoirs of Edmund Ludlow. With original papers.

Original Letters. Sir Henry Ellis.

Autobiography of Sir Symonds d'Ewes.

Nicholas Papers. Correspondence of Sir Edward Nicholas. Ed. G. F. Warner (Camden Society).

Life of Marie de Medicis. J. Pardoe.

Henri-Qiiatre and Marie de Medicis.

Journal de Jean Heroard. Publ. Barthelemy.

Regency of Anne of Austria. Freer.

Dictionary of National Biography.

Memoirs of Pere Cyprian de Gamache.

Madame. Julia Cartwright.

Henriette Anne d } Angleterre. Comte de Baillon.

Zeller. par E.

Soulie et E. de

APPENDIX II

577

Memoires de Madame de la fayette: Histoire de Madame Henriette d'Angleterre.

Sir John Reresby's Memoirs. Journal d 1 Olivier Lefevre Ormesson. Muse Historique. Loret. Journaux de Pierre VEstoile. Memoires du Comte de Brienne. Memoires du Cardinal de Retz. Memoires de Madame de Motteville. Memoires de Mademoiselle de Montpensier.

Memoires du Comte Leveneur de Tillieres. Ed. M. C. Hippeau. Journal de ma Vie. Le Marechal de Bassompierre. Sully's Memoires.

ABINGDON, King and Queen part

at, 298 Abruissel, Father Robert d',

369

Alexander VII., Pope, 475-6 Amiens, Henrietta at, 47 Ancre, Marquis d', 12. See

Concini

Andover, Lord, 176 Anjou, Gaston, Due d', 8, u.

See Orleans Anjou, Philippe, Due d', 313,

471, 495. See Orleans Anne of Austria, Queen of France, 16, 18, 23, 24, 26, 35, 47-Si» 58, 69, 92, in ; Regent, 294, 300, 310, 313, 316 seq., 339, 355, 370, 371, 380-2, 387, 389, 402, 403, 413, 421, 429, 446, 449, 455, 464, 471, 477, 478, 481, 529, 534, 535, 549 ; her death, 559 Anne, Princess, birth of, 151 ;

death, 218

Argyle, Marquis of, 438 Army Plot, 222 Arras, battle of, 462 Arundel, Countess of, 178 Arundel, Earl of, 198, 199, 267 Ashburnham, John, 222, 360,

373 Aubigny, Lord, 543

VOL. II.

Augustine's Hall, St., Canterbury, 60

BAMFIELD, COLONEL, 369

Barbarini, Cardinal, 161

Barram Downs, 59

Barrett, Sir Francis, 307

Basset, Mistress, 168

Bassompierre, Marechal de, 9, 67 ; his mission, 87 seq., 96 death, 317

Bazini&re, Hotel de la, Henrietta's Paris residence, 559

Beauvais, Henrietta at, 419,

537

Bedford, Earl of, 289 seq.

Bellievre, M. de, French ambassador, 355, 359

Bennet, Sir Henry, 476, 489

Berkeley, Justice, 155

Berkeley, Sir Charles, 515, 521,

523

Berkeley, Sir John, afterwards Lord, 373, 414, 418, 457, 469, 473, 487, 488 Berkshire, Earl of, 326 Bernini, the sculptor, 133 Berulle, Pere de, 42, 49 Berwick, Treaty of, 202, 203 Blainville, M. de, French ambassador, 80 Blois, Henrietta at, 16

579 1 8

INDEX

Bodleian Library, royal visit to,

171

Bonzy, Cardinal de, 14 Boulogne, Henrietta at, 55 Bourbon, Henrietta at, 311, 440 Bossuet, funeral oration, 568 Bos vile, Major, 369 Boswell, ambassador at the

Hague, 259-61 Boyle, Lady, 420 Breda, Treaty of, 419 Breves, M. de, 15 Brienne, Comte de, 46-8 Bristol, city of, surrenders to the

King, 289 ; given up by Prince

Rupert, 344 Bristol, Earl of, 406 Bristol, George, Earl of, 488, 546,

548. See Digby Broussel, M., 381, 382 Browne, Sir R., British resident

in Paris, 380, 432, 456, 471 Bruges, Charles II. at, 487 seq. Buckingham, George Villiers,

ist Duke of, 25, 32-5, 45-5 2 »

63, 68-70, 75, 77-83, 85, 88-96,

98, 99 ; murder of, 100 seq. Buckingham, George Villiers,

2nd Duke of, 383, 443, 526,

527, 529

Burt, Francis, 154 Byron, governor of the Tower,

255

CADENET, MARECHAL DE, 21, 22 Cadiz, expedition against, 68,

81

Campbell, Lady Anne, 420 Canterbury, Charles I. at, 55 ;

Henrietta at, 59-60, 517 Capel, Lord, 354 Capuchins in England, 91, 113-5,

242, 545

Carisbrook Castle, Charles I. at,

378, 386 Carleton, Sir Dudley, 69, 72,

134. See Dorchester Carlisle, Countess of, 36, 140,

143, 144, 183, 197, 240, 248,

251, 383 Carlisle, Earl of, 35 ; sent to

Paris, 36 seq., 46, 102-4, 121,

142, 143

Carlyle, Thomas, quoted, 63 Carnarvon, Lady, 170 Carnarvon, Lord, 170, 171 Castlemaine, Lady, 538, 540 Catharine of Braganza, Queen,

537, 538, 540, 543, 546, 547

Catholic League, 2

Cavendish, Lord Charles, 283, 284

Chaillot, 412 seq., 421, 454

Chapelles, Comte de, 549, 550

Charenton, 437

Charles, Archduke, 5

Charles I., King, 19, 24 ; in Paris, 25, 26 ; in Spain, 28, 29 ; his marriage negotiations, 38 seq. ; meeting with Henrietta, 54 seq. ; his coronation, 78, 79; dismisses her suite, 83-6 ; quarrels with her, 89 ; relations with Buckingham, 78, 81, 93, 98, 99; harmony between King and Queen, 96 ; hears of Buckingham's murder, 101 ; its effect upon him, 102, 103; relations with Henrietta, 103, 104, 109, in; attitude on religious matters, 112-5, 176, 177; Henrietta's influence upon, 118-23; visits Scotland, 128 ; Scottish coronation, 1 29 ; love of art, 1 34; affection for Hamilton, 141, 142;

581

has smallpox, 145 ; relations with Panzani, 161, 162; receives his nephews, 165 ; visits Oxford, 170-2; presses collection of shipmoney, 172; forces liturgy on Scotland, 178 seq. ; receives Marie de Medicis, 190 ; at York and Berwick, 201, 202 ; signs Treaty of Berwick, 202 ; adopts Wentworth as counsellor, 205 ; calls a Parliament, 206, 215 ; goes north, 213 ; conduct towards Straf-ford, 221 seq. ; goes to Scotland, 236 ; letters to Nicholas, 238, 239 ; in the City, 244 ; his fears for the Queen, 247-9 ; attempts the arrest of the five members, 250, 251 ; leaves London, 253 ; parts with the Queen, 258 ; refuses to give up the militia, 265 ; sets up the royal standard, 268, 269 ; letter to Henrietta, 274, 275 ; his anxiety, ibid. ; influenced by the Queen, 280, 281 ; meeting of King and Queen, 285, 286 ; at Oxford, 286 seq. ; final parting with Henrietta, 298 ; letters to her, 304 seq. ; at Oxford, 326 seq. ; successes, 336; defeated at Naseby, 337 ; refuses concessions, 340, 341 ; in the hands of the Scotch, 354; wavering policy, 359 ; with the army, 373 ; at Hampton Court, 374 ; his injunctions to his children, 375 ; in the Isle of Wight, 378, 385 seq. ; trial, 387 ; death, 388 Charles II., King, born, 115, 116, 149; first letter, 150, 182;

his dream, 211, 212; meets his mother, 285; 309; parts with his father, 326, 327; marriage projects, 334, 335, 345 ; his movements, 347 seq. ; at Paris, 355 seq., 362, 363, 370 seq., 376, 377, 384, 385 ; succeeds his father, 388 ; in Holland, 397-401 ; at Com-piegne and Paris, 403 seq. ; his quarrels with the Queen, 405 seq. ; leaves Paris, 410 ; at Jersey, 411 seq. ; at Beauvais, 419 ; signs Treaty of Breda, ibid. ; in Paris again, 434 ; his relations with Mademoiselle, 440 seq., 445 seq. ; defends Hyde, 452 ; disputes with his mother, 456, 457 ; described, 457, 458; leaves Paris, 460 ; continued dissension, 462 ; attitude with regard to attempted conversion of Gloucester, 466 seq. ; reconciliation with his mother, 475 ; negotiations with the Pope, 475, 476 ; quarrel between the King and Duke of York, 487, 488 ; interferes between his sister and Harry Jermyn, 489, 490 ; alliance with Spain, 491 ; at Fontarabia, 499; visits his mother, 500 ; Mazarin's coldness, 501 ; improving fortunes, 503, 504 ; Restoration, 505 ; conduct re Duke of York's marriage, 512 seq. ; grief at Duke of Gloucester's death, 514 ; meets his mother at Dover, 517 ; consents to his sister's marriage, 519, 524 ; the Princess Royal's death,

522 ; takes his mother to Portsmouth, 526 ; his marriage, 537 ; meets his mother at Greenwich, 538 ; fondness for Duke of Monmouth, 539 ; affection for his mother, 540 ; relations with his wife, 538, 542, 546, 547 ; loyal to Clarendon, 546, 548 ; anti-French proclivities, 551 ; letter to Madame, 563

Charles Lewis, Prince Palatine, 164 seq., 226, 235, 256, 269, 299

Chateauneuf, M. de, French ambassador, in, 118, 123

Chaulmes, Duchesse de, 48

Chevreuse, Due de, 33 ; Charles' proxy, 44, 63, 209

Chevreuse, Duchesse de, 19, 23, 33, 34,46, 58,63, 70, 123, 183, 191, 197, 203, 208, 209, 316,

317

Chillingworth, 292 Chilly, Henrietta's visit to, 484

seq. Cholmley, Sir Hugh, governor

of Scarborough, 279 Cioli, Tuscan secretary, 12 Clarendon, Edward Hyde, ist

Earl of, reconciliation with

the Queen, 524, 525, 539,

546, 548 ; his disgrace, 561,

562 ; also constantly quoted.

See Hyde Clermont, Jesuit college at, 463

seq. Cologne, Charles II. at, 463

seq. Coloma, Don Carlos de, Spanish

envoy, 122 Colombes, Henrietta's country

home, 500, 505

Comminges, M. de, French ambassador, 546, 5502 Compiegne, Charles II. at, 403 €on, papal agent, 163, 164, 175

seq., 197, 219

Concini, 5, 13, 16. See Ancre Conde, Prince de, 392, 421, 427,

442, 445, 492, 530, 557, 558 Conde, Princesse de, 13, 413 Conti, Prince de, 421, 456 Conti, Princesse de, 50 Conway, Lord, 55, 84, 161, 170,

207, 209, 370

Conyers, Sir John, letter of, 370 Cordelier sent to England, 30, 31 Cosins, Dean, 430, 431, 463, 464,

467 Cosnac, Daniel de, Bishop of

Valence, 530

Cotolendi, Carlo, quoted, 541 Cottington, Lord, 108, 121, 160,

364, 384, 406, 407, 417 Covenant, the, 187, 295 Cowley, Abraham, 329 Crofts, Lord, 469, 499, 500, 539 Cromwell, Oliver, 373, 374, 449,

474, 492, 493 ; death of, 494,

495

Cromwell, Richard, 497 Crowther, Dr., 512 Culpepper, Lord, 360, 363

DALKEITH, LADY, 302, 361, 377.

See Morton Danby, Earl of, 172 Darley, Mr., 282 Dartmouth, 3rd Earl of, 514 note Davenant, the poet, 297, 361 Davys, Lady Eleanor, 106, 107 Denbigh, Countess of, 68 Denton, Dr., letter of, 213 Derby, Countess of, 96, 365, 366,

510, 515, 517-9, 525, 543

Desmond, Earl of, 200, 201

D'Ewes, Sir Simond, quoted, 62, 156

Digby, George, Lord, 219, 220, 249, 250, 254, 257, 258, 268, 269, 288, 330, 333, 338, 339, 350 seq., 364, 378, 396, 400, 466, 428, 429. See Bristol

Digby, Sir Kenelm, 330, 343-5

Digges, Sir Dudley, 82

Dillon, Lord, 246

Disraeli, Mr., 119

Dorchester, Viscount, 102, 108, 114. See Carleton

Dorset, Lady, 115, 131

Dorset, Lord, 113, 169

Du Buisson, envoy to England, 20, 21

Dumoulin, Dr., prebend of Canterbury, 544, 545

Dunbar, battle of, 422

Dunes, Battle of the, 492

Dunkirk, taken by Cromwell, 492 ; sale of, 548

Duquesne, Dr., 567

EDWARD, PRINCE PALATINE, 492 Eliot, Sir John, 31, 63, 81 Elizabeth de Bourbon, Queen of Spain, 15, 29 ; her death, 313 Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, 1 16, 130, 165-7, 226, 245, 246, 256, 259, 261, 461, 472

Elliot, Thomas, 405-7 Essex, Earl of, 198, 199, 214, 253,

301, 302

Evangelical Alliance, 2 Evelyn, John, quoted, 311 Exeter, Queen at, 299 seq.

FAIRFAX, GENERAL, 277, 373, 379

Falkland, Viscount, 134, 288,

292 ; his death, 293 Falmouth, Queen sails from, 307 Fayette, Madame de la, quoted,

526, 531

Felton, John, 101, 102 Fielding, Lord, 95 Fiennes, Madame de, 549-51 Finch, Sir John, Lord Keeper,

220, 268

Five members, attempted arrest of the, 250 seq. Fontarabia, Charles II. at, 499,

500 Fontenoy-Mareuil, Marquis de,

French ambassador, 114, 123

seq.

Forster, John, quoted, 99, 109 France, M. Anatole, quoted, 506,

531

Francis, St., de Sales, 17 Fronde, the, 387 seq., 441 seq. Fuller, Thomas, quoted, 218

GAMACHE, PERE CYPRIAN DE, 115, 304, 361, 393, 396, 516, 525, 528, 529, 531, 543, 564-7

Gamester, The, Shirley's play,

H7 Gardiner, S. Rawson, quoted, 92,

156, 205, 229, 286, 340 Garrard, Lord, 457 Garrard, Master of the Charterhouse, 178

Glamorgan, Earl of, 345 Glasgow, Archbishop of, 129 Gloucester, Duke of. See Henry Goring, George, the younger, 199, 222 seq., 241, 242, 267,

329

Goring, Sir George, afterwards Lord, 71, 104, 130, 143, 154, 168, 261, 267. See Norwich

INDEX

Green, J. R., quoted, 99 Griffin, Duke of Gloucester's

attendant, 467 Grignan, M. de, French agent,

387

Guiche, Comte de, 535-7 Gustavus Adolphus, King of

Sweden, 121

HAGUE, The, Buckingham at, 75, 76 ; Marie de Medicis at, 189 ; Henrietta at, 259 seq.

Hamilton, Marquis of, 141, 142, 199, 279

Hamilton, William, 163

Hampton Court, 73

Hampden, John, 63, 83, 181

Harcourt, Comte d', French ambassador, 294, 295

Hatton, Lady, 165

Hatton, Lord, 398-400,415, 416, 419, 423, 462, 466, 467, 471, 473, 474, 483

Heenvliet, Dutch ambassador, 255, 482, 483

Henri-Quatre, i seq. ; murdered, 9-1 1

Henrietta Maria, Queen of England, birth, i ; infancy, 6 ; her father's murder, 10 ; childhood, 13; baptism, 14; education, 15 ; at Blois, 16, 17 ; at her sister's marriage, 17 ; at court, 18 ; marriage projects, 19 seq. ; the Comte de Soissons her suitor, 24 ; Charles I. sees her, 25 ; her marriage negotiations, 30-44 ; betrothal and marriage, 44 ; parts with her mother, 49 ; arrives in England, 53 ; at Dover, 55 ; meeting with

Charles I., 56 ; first disagreement, 59 ; enters London, 60 ; first impressions of her, 62 ; alleged pilgrimage, 67 ; quarrels at court, 67, 68, 70, 71 ; the King's complaints of her, 72-5 ; refuses to be crowned, 78-80 ; a fresh quarrel, 80, 81 ; her retinue ejected, 83-6 ; Bassompierre and Henrietta, 87-90; domestic peace restored, 94 seq. ; affection for the King, 103, 104 ; birth and death of her first child, 105-8 ; the King and his wife, in ; lays the corner-stone of Capuchin church, 113; birth of Charles II., 115 ; her description of him, 116; her influence over the King, 118 ; its limits, 120 seq. ; birth of Princess Mary, 128 ; of James II., 131 ; relations with Earl of Portland, 136; with Laud, 138; with Wentworth, 139; her friends at court, 142-5 ; takes part in a masque, 146, 147 ; letter to Prince Charles, 150 ; letters to Duchess of Savoy, 151, 152; popular distrust of her, 156, 157; relations with Panzani, 161 seq. ; visit to Oxford, 170, 171 ; religious quarrels, 176-8 ; her account of Scotch troubles, 179 ; letters to Wentworth, 185, 186, 201 ; receives her mother, 190 ; death of a child, 198 ; interferes in military appointments, 199 ; quarrels with Strafford, 207 ; Henrietta, Strafford and Vane, 210, 211 ;

585

appeals to the Pope, 212, 220 ; the Queen and Parliament, 219 ; attempts to save Straf-ford, 220, 221 ; letter to her sister, 226, 234 ; her account of the Army Plot, 223-7 ; her plans frustrated by Parliament, 233, 234; parts with her mother, 236 ; at Oatlands, 238 seq. ; alleged design to carry her off, 241 ; letter to Nicholas, 243 ; still in favour of resistance, 245, 246 ; rumour of her impeachment, 247-9 ; her indiscretion, 250, 251 ; leaves London, 253 ; goes to Holland, 258 ; at the Hague, 259 seq. ; her letters, 260 seq. ; her labours, 266 seq. ; in danger at sea, 273, 274 ; arrives in England, 276 ; fired upon, ibid. ; in the north, 277 seq. ; impeached in Parliament, 282 ; marches south, 283 ; meets the King, 285 ; demands a peerage for Jermyn, 286 ; at Oxford, 287 seq. ; letters to Newcastle, 293, 294, 296, 322 ; hopes of French aid, 394 ; ill health, 297 ; final parting with Charles, 289 ; at Exeter, 299 ; birth of her youngest child, 301 ; escape from England, 303, 304 ; her condition, 307 ; at Bourbon, 311 ; reception in Paris, 313 ; installed at the Louvre, ibid. ; appearance in middle age, 317 ; economies, 318 ; relations with Jermyn, 320, 321, 415, 416, Appendix, 571-3 ; work in Paris, 323 ; the Louvre court, 329; de-

clines to receive the Nuncio publicly, 331; illness, 333; correspondence with the King, 335-8 ; labours, 341 ; urges the Prince's coming to Paris, 348 seq. ; the Queen and Mademoiselle, 356, 357, 362, 363 ; her youngest child brought to her, 361 ; interferes in Derby lawsuit, 365, 366; relations with Hyde, 377, 378 ; her poverty, 380, 39°> 39i ; interview with Broussel, 381 ; as peacemaker, 381, 382 ; visited by de Retz, 390 ; receives tidings of the King's death, 394 seq. ; position at Paris, 398 ; her hopes, 401 ; quarrels with Charles II., 405-8 ; is visited by Mademoiselle, 408-10 ; her religion, and Chaillot, 412 seq. ; feeling against her, 414 ; treated by Charles with reserve, 410, 417 ; meets him at Beauvais, 319; disapproves his policy, 319, 320; poverty, 321 ; her daughter's death, 322 ; quarrels with Duke of York, 423, 424; mourns her son-in-law, 425 ; Ormond and the Queen, 427, 428 ; relations with Lord Digby, 429 ; conduct towards Protestants, 430, 431 ; recalls Duke of York to Paris, 432 ; relations with Nicholas, 436; dissensions at Paris, 438 seq. ; promotes Charles* suit to Mademoiselle, 440 seq. ; views as to the matches proposed for James and Mary, 443 ; position at Paris, 444,

INDEX

445 ; at Saint-Germain, 446 ; at the Palais Royal, ibid. seq. ; feud with the Chancellor, 447 seq., 460 ; receives Duke of Gloucester, 450 seq. ; letter re Henriette-Anne, 455 ; renewed disputes with Charles, 456 seq. ; attempts Gloucester's conversion, 462-70 ; final parting with him, 470 ; the Queen and Mazarin, 474 ; reconciled with her children, 475 ; visit from the Princess Royal, 479 seq. ; visits Mademoiselle at Chilly, 484-7 ; difficulties of her position in Paris, 492 ; appeal to Cromwell, 493 ; receives news of Cromwell's death, 495 ; relations with Charles II., 498-500 ; receives Reresby at the Palais Royal, 501, 502 ; gossip concerning her, 503, 543 ; joy at the Restoration, 505 ; her daughter's marriage in question, 506, 509 ; fresh overtures to Mademoiselle, 509, 510; anger at Duke of York's marriage, 511 seq. ; visits England, 516; arrival, 517 ; her melancholy, 521, 522 ; accepts the Duchess of York. 524, 525 ; and is reconciled with Clarendon, 525 ; returns to France, 527 ; arrival there, 528 ; anxieties concerning Madame, 532 seq. ; return to England, 537 ; at Greenwich, 538 ; changes in her character, 541 ; happiness, 542, 543 ; her household, 543-5 ; death of her sister, 547 ; quarrel in her

household, 549-51 ; friendliness towards France, 551, 552 ; ill health, 553 ; return to France, ibid. ; peaceful years, 554-6; acts as mediatrix between England and France, 557 seq. ; the end approaching, 563 ; last illness, 565 ; and death, 566 ; funeral, 568 ; and character, 568-70

Henriette-Anne, Princess, birth of, 301, 302 ; in France, 361, 362, 390, 407, 408, 413, 455 seq., 471, 477, 478, 481, 482, 495> 504, 5°5 ; marriage in question, 506 seq. ; in England, 518-20, 522, 523, 526, 527 ; marriage to Monsieur, 528, 530 ; character, 530, 531 ; married life, 532 seq. ; her child's birth, 536, 537, 557 seq., 568

Henry, Prince, Duke of Gloucester, 375, 388 ; released, 450 ; in Paris, 451 seq., 458, 459; his attempted conversion, 462 seq. ; removal to Cologne, 471, 472 ; his death, 514

Herbert, Lord, ambassador at Paris, 26

Herbert, Sir Edward, 457

Heroard, Jean, 5

Hertford, Marquis of, 240, 293

Holland, Earl of, 41, 46, 63, 125 seq., 142, 143, 168, 183, 184, 199, 239, 240, 246, 253, 289 seq., 382, 383; letters to Buckingham, 69

Hollis, English ambassador, 557,

558

Holmby House, the King at, 368 Honey wood, Sir Robert, 341

587

Hope, John, letter of, 143 Hctham, Sir John, 254, 266, 284 Howell, quoted, 63 Hudson, Geoffrey, the Queen's

Dwarf, 114, 162, 261, 303, 312 Humfrey, Andrew, 157 Hutchinson, Mrs., quoted, no Hyde, Anne, lady-in-waiting to

Princess of Orange, 461, 483 ;

her marriage, etc., 511 seq. ;

recognised by Henrietta, 524,

525

Hyde, Sir Edward, Chancellor, 225, 280, 351, 354, 364, 377, 378, 384, 385, 398-400, 406 seq., 415, 417 seq., 423, 429 seq., 435 seq., 443, 450, 452, 456, 460, 461, 466, 471, 483, 487, 489, 500, 516. See Clarendon

JAMES I., KING, 21, 22, 25, 26

James, Duke of York, 396, 410, 422, 424, 426, 428, 431, 432, 437, 439, 440, 449, 452, 453, 456, 459, 462, 466, 467, 468, 470, 471, 473-7, 479, 481-4, 552, 553, 556; birth, 128, 131, 266, 285, 367, 375 ; escape from England, 378 ; in Paris, 392 ; quarrel with the King, 487-9, 491 ; marriage, 511 seq.

Jars, Chevalier de, 128 seq.

Jermyn, Henry, afterwards Lord, 126-8, 144, 168, 204,207, 222 seq., 268, 284 ; made a peer, 286, 287, 288, 303, 310, 320, 321, 340, 341, 343, 353-5, 360, 364, 390, 394, 399, 400, 403, 404, 415, 416, 418, 423, 429, 437 seq. t 457, 468, 469, 480, 482, 489, 490, 498, 499,

503, 513, Appendix, 571-3.

See St. Albans Jermyn, Henry, the younger,

484, 487-90 Jersey, Prince of Wales at, 349

seq. ; Charles II. at, 411 seq. Jonson, Ben, 148 Juxon, Bishop of London, 163

KENSINGTON, LORD, envoy to

Paris, 31 seq. See Holland Ker, Lord, 201

LANOY, MADAME DE, 50, 51

Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, 79, 101, 108, 116, 129, 138-40, 159, 169, 170-3, I75-7* 179, 191

La Valliere, Louise de, 535

Legge, Robin, 284

Leicester, Earl of, letters to, 119, 181, 189, 197,

Lennox, Duchess of, 60

Lenthall, Speaker of the House of Commons, 327

Leopold, the Emperor, 519

Lesley, Sir Alexander, 284

Long, secretary to Charles II.,

415

Longueville, Due de, 421, 528 Longueville, Mademoiselle de,

443

Loret, quoted, 451, 492, 493 Lorraine, Duke of, 424, 426, 428,

445

Louis XIII., King, 6,10, 1 1, 45-7, 91, in, 189, 204; death of, 294

Louis XIV., King, 313, 354, 355, 382, 404, 413, 446, 456, 464, 477-9, 48i, 482, 496, 507-9, 532, 533,535, SSL 552,557, 558, 560, 565 ; birth of, 191

INDEX

Louise, Princess Palatine, 472 Louvre, Henrietta established at,

313 Lovel, Mr., Duke of Gloucester's

tutor, 462 seq, Luynes, Due de, 13, 19-21

MADELEINE, MERE, 18

Mancini, the sisters, 477, 478, 501, 513, 514

Marguerite de Valois, Queen, 14