Chapter 1

LAKE ARROWHEAD TO RUNNING SPRINGS

The 1930s were halcyon years for skiing at Lake Arrowhead in the San Bernardino National Forest north of San Bernardino. Skiing flourished on the slopes around the village, and it was one of the first and favorite destinations for Southern California skiers. The Los Angeles Junior Chamber of Commerce, a dynamic force in the promotion of winter sports in the 1930s, chose Lake Arrowhead for its first winter carnival in 1927. A ski jump was built at Lake Arrowhead in 1932 and was often the central focus of the headline-attracting ski meets and winter carnivals, drawing ski jumpers from all over the nation.

Two of Southern California’s pioneer ski mountaineers and ski instructors frequented the slopes of Lake Arrowhead and directed ski schools and winter sports programs there. First was Walter Mosauer, recruited by the North Shore Tavern to “reveal the mysteries of intricate Christianias, Telemarks and Tempo Turns.”10 Though it was advertised as a North Shore Tavern program, Mosauer’s ski school took place at Keller Peak near Snow Valley, where an abundance of ski terrain, situated above six thousand feet, was often blanketed with more plentiful snow than the hills near the village at Lake Arrowhead. Later in the 1930s, Otto Steiner worked as director of the Lake Arrowhead Ski School. Much of Steiner’s winter program also took place at Keller Peak.11

But all of these activities occurred without the luxury of mechanical uphill transportation. Edi Jaun and John Elvrum teamed up and built Lake Arrowhead’s first mechanical tow in 1938. The sling lift, situated on a hill next to the Lake Arrowhead village school (where the fire station stands today), was easily accessible to guests staying at the Village Inn or any other local lodges. The 1,200-foot tow provided access to a wide choice of runs, from novice to expert. When snow conditions were favorable, the pair would use the lift to teach resort guests and locals. The two men were very active in promoting skiing opportunities and instruction to mountain residents.

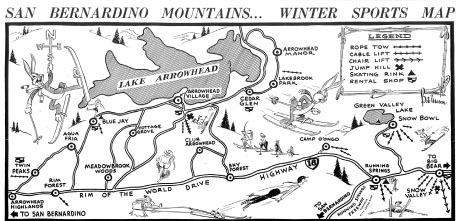

A 1930s map showing winter sports facilities for Lake Arrowhead winter visitors. The Lake Arrowhead North Shore Ski House, located at Fish Camp, was renamed Snow Valley in 1937. Note the emphasis on clear winter roads. Lack of access to ski areas was an obstacle for Southern California skiers prior to the advent of effective snow removal methods.

Edi Jaun (kneeling, far left) and John Elvrum (kneeling, third from left) teamed up to build Lake Arrowhead’s first ski tow, a sling lift, in 1938. Upon his arrival in 1921, Jaun was one of Lake Arrowhead’s first skiers. In addition to the Lake Arrowhead tow, he was also involved in the construction of the sling lift at Big Bear Lake. Elvrum, a championship ski jumper, went on to develop Snow Valley and owned and operated the area for more than thirty years.

Unfortunately, three low-snow years followed the construction of the tow, and it often sat idle. Tony Crowder bought the tow in the 1940s, but he, too, had limited success with the area. The snow season was often short and unpredictable, the low elevation of 5,174 feet frequently resulting in rain rather than snow.

Born on February 23, 1901, in Bern, Switzerland, Jaun and his family settled in Scranton, Pennsylvania, when he was six months old. For reasons unknown, he returned to Switzerland when he was six years of age and remained there for the next thirteen years. He climbed and skied all over Switzerland, firmly establishing his love of the mountains and skiing. In 1920, Jaun returned to the United States to live with an uncle in Pennsylvania.

Jaun’s uncle learned that Lake Arrowhead village was being developed by J.B. Van Nuys and managed by Paul Bauman, a Swiss engineer. In 1921, Jaun came to Lake Arrowhead to look for work. By 1923, he owned the south shore marinas on the lake. He and his nephew Wilmer owned and operated the marina until it was sold in 1960.

Much of the early skiing that Jaun did around Lake Arrowhead was more for necessity than for sport. Since he was the only person working for the Lake Arrowhead Corporation who knew how to ski, he was often chosen to do winter repairs on downed telephone lines and carry mail on skis from the main highway to Lake Arrowhead. This trek was twenty-five miles round trip, and for two years, Jaun carried the mail once a week during winter when necessary.

Jaun and his wife, Eli, were expert cross-country skiers and ski jumpers. Edi competed in local races and won the five-mile cross-country race during the Seventh Annual Winter Sports Carnival held at Lake Arrowhead in 1933. He finished with a time of thirty-nine minutes, forty seconds. Eli competed in various cross-country races throughout the state and was often referred to as a star woman racer representing the Lake Arrowhead Ski Club. The two were also accomplished ski mountaineers. In 1934, along with five others, they scaled the summit of San Gorgonio on skis. After camping at the 6,000-foot level on Saturday night, the group started their ascent Sunday before dawn. Traveling by moonlight, they reached the 11,503-foot summit at 10:00 a.m. The others in the group were Walter Mosauer; Frederick C. Ripley Jr., president of the California Ski Association; Cliff Youngquist; Louis Turner; and Chet Allen.12

Edi is not known for his jumping, but in January 1934, a number of national newspapers featured a photograph of Halvor Halstad and Edi practicing a double jump that was to be featured during the upcoming California State Ski Championships.

Eli was one of less than a handful of female jumpers in the United States in the 1930s. In the December 1934 Utah Ski Club tournament, Edi competed in the A-class jumps, and Eli was the only woman who signed on for the “feminine class.”13

Winter carnivals and ski jumping dominated the 1930s winter sports scene, but these activities were severely limited or came to a standstill once World War II broke out. But when the war ended in 1945, there was great interest in reviving the popularity of Lake Arrowhead and other Southern California winter sports centers to levels equal or above those experienced in the 1930s.

Les Salm, Lake Arrowhead’s first fire chief, was active in establishing postwar skiing at Lake Arrowhead.14 Salm went to work for the Lake Arrowhead County Fire District on July 20, 1942. He had been a San Bernardino National Forest ranger since 1926–27 and spent many of his fourteen years with the Forest Service patrolling on motorcycle. He built a rope tow in Lake Arrowhead (the exact date of construction is unknown) and dubbed it the Lodge Hill Ski Tow. It was operating in the mid- to late 1940s and was one of the locations where Salm conducted early experiments with snow making. In Salm’s daybooks from 1947–48, there is no mention of this ski tow, but he does provide an outline of his historic attempts at making snow.

The Lodge Hill Ski Tow, a rope tow Les Salm built in Lake Arrowhead in the 1940s, was the beneficiary of his snow-making experiments in 1947–48. Snowfall at Lake Arrowhead was often marginal, prompting Salm to begin experimenting with snow making in 1947. Salm’s young son David pauses for a break on a slope blanketed with man-made snow. Courtesy of Jill Salm Walker.

This skier has discovered a unique way to rest as he ascends the Lodge Hill Ski Tow. Courtesy of Jill Salm Walker.

The first successful snow making at a ski area in the United States was at Walter Schoenknecht’s Mohawk Mountain Ski Area in Cornwall, Connecticut, in 1950–51. In 1955, Moonridge Meadows, now Big Bear’s Bear Mountain Ski Area, was the first California ski area to successfully implement snow making. Salm’s approach was different from others who attempted to manufacture snow. Snow making then and now employs a system of hoses and nozzles. Salm’s method was cloud seeding.

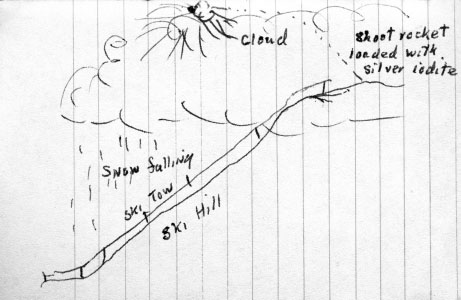

Salm may have been inspired by work that had taken place at General Electric in Schenectady, New York. In November 1946, Dr. Bernard Vonnegut discovered that microscopic silver iodide crystals acted as a nucleus for water vapor to form ice crystals. General Electric rented an airplane and released dry ice into the clouds on four days in November and December 1946. On the last day of the seeding, the greatest snowfall of the winter blanketed Schenectady. It is likely that Salm learned of this work and felt it could be the answer to Lake Arrowhead’s often marginal snowfall. In early November 1947, Salm consulted with Big Bear Lake’s Clifford Lynn and the Lake Arrowhead Chamber of Commerce about snow making. He then went forward with his experiments and documented these activities in his daybooks. Below are his narratives of his snow-making attempts during the 1947–48 season:

November 14, 1947—Made preparations to precipitate snow or rain with dry ice and balloon. Temperatures did not drop low enough.

November 15, 1947—Cold north wind blew rain clouds away. Snowed at Big Bear and fog iced the trees. Clouds too warm here to send up dry ice balloons.

November 20, 1947—Received hydrogen and dry ice for snowmaking.

November 22, 1947—Snowed 1½ inches between 4am and 8am from putting dry ice in the clouds at S.P.L. O. [Strawberry Peak Lookout]. Sent six hydrogen balloons with dry ice into clouds and it snowed from 9am to 2pm.

December 3, 1947—At 2pm I released 2 balloons with dry ice from Summit. Nothing happened. Cloud was too warm. About 4:20pm Rusty Wiles and I flew dry ice with a box kit into clouds from Strawberry Peak Lookout. In about 10 minutes it began to snow on the Peak and rain fell at Blue Jay, Alpine, and Lake Arrowhead. After snowing for 20 minutes, the kit broke away and it stopped snowing almost immediately, but rain continued to fall at lower elevations.

January 25, 1948—Moist marine air swept into Southern California today…This is the first moisture in 7 weeks of droughth [sic]. I tried to get dry ice to fly into the fog with box kit to start precipitation.

February 4, 1948—9pm went to Crest Summit and attempted to fly dry ice into clouds but wind was too gusty to launch kite.

Salm’s snow-making experiments were the first attempts to manufacture snow for skiing in California and some of the earliest in the United States.

In February 1947, the season before Salm began his snow-making efforts, Walt and Wynne Harmon advertised “California’s new winter sports center” with the opening of a two-thousand-foot sling lift and rope tows at Lake Arrowhead. They experienced the frustration that marginal snowfall could inflict on Southern California ski area operators, and the lifts ran intermittently.

A January 1947 advertisement for Walt and Wynne Harmon’s Lake Arrowhead ski area. They spared no expense outfitting the area with the latest in ski rentals, clothing and accessories, but winter weather was fickle, and the area was short-lived due to inadequate snowfall.

The last attempt at developing a successful Lake Arrowhead ski enterprise took place during the 1961–62 season. The Lake Arrowhead Ski Bowl opened with a double rope tow. In the event of no natural snow, it was reported that artificial snow “will be cut and spread a fresh two inches deep across the bowl each night after December 15 [1961].”15

In addition to the various Lake Arrowhead tows, other lifts sprang up along slopes from Lake Arrowhead to Running Springs. Cedar Glen, nestled into the trees at the east end of Lake Arrowhead, began as a lumber operation. In 1916, lumberman John Suverkrup subdivided fifty-six lots and named it Cedar Glen. As the homesites developed and the town grew in popularity, the need for a business district at the east end of the lake arose. Suverkrup then developed a small grocery store and rental cabins.

By the late 1940s, Cedar Glen was a destination for all manner of winter sports enthusiasts. Visitors could take in a sleigh ride from the O.P. Doan stables located at the entrance to the town. Beyond Cedar Glen, at the foot of Hook hill on the county highway, skiers could ride the one-thousand-foot-long ski tow that operated throughout the winter season. Ski instructors were available for those wanting to polish their skills or for novices just learning the fundamentals. For non-skiers, toboggan runs and sledding hills were on hand.

A hand-drawn sketch from Les Salm’s October 1947 fire service daybook illustrating his plan to produce man-made snow on his Lake Arrowhead ski hill. His snow-making attempts, for the specific purpose of augmenting the snowpack for skiing, were the first in California. Courtesy of Jill Salm Walker.

A whimsical 1949 winter sports map showing the location of the many ski tows that sprang up between Twin Peaks and Snow Valley.

A no-frills 1949 advertisement for Cedar Glen’s rope tow.

Blue Jay, a quaint community located approximately one mile from Lake Arrowhead Village, operated a rope tow from 1948 through 1959. The tow, 500 feet long with a 150-foot rise, ran whenever snow conditions allowed. At an elevation of 5,203 feet, the slope often suffered from marginal snowfall.

Tom Preston founded and operated O-Ongo Ski Tows. Located two and a half miles west of Running Springs on Highway 18 at an elevation of 6,400 feet, the area opened during the 1945–46 season and, by the mid-1950s, operated five rope tows providing access to slopes for all levels of skiers. The area closed in 1957, another victim of low elevation and unpredictable snowfall.

Howard Martin ran a one-thousand-foot tow just outside Running Springs in the 1940s. In 1947, Martin left Running Springs and became the manager of the ski tows at Conway Summit near Bridgeport in the Eastern Sierra Nevada. Lloyd Soutar also operated a tow in Running Springs. In the mid-1950s, he installed an eight-hundred-foot tow, mostly for his family to use, immediately west of the current elementary school.

Blue Jay, a small community adjacent to Lake Arrowhead, was often overshadowed by the more popular Lake Arrowhead. In the 1950s, Blue Jay also began providing a variety of ski facilities, including a rope tow, to entice winter sports enthusiasts to visit the small town.

Beginning in the 1949–50 season, two rope tows, both 750 feet long with a 175-foot rise, operated in Running Springs. It is unknown who operated these tows, but Bob Mason provided ski instruction. They operated through the mid-1950s, and then, beginning with the 1955–56 season, this area became known as Wintergarten. The tows continued to operate until sometime in the 1960s.

A 1949 advertisement for Camp O’Ongo’s Ski Hill highlighting facilities and amenities that catered to skiers.

In January 1965, Ski the Rim opened on Rim of the World Highway in Running Springs. One 600-foot rope tow with a 250-foot vertical rise operated on the four-acre hill. Its elevation often resulted in marginal snowfall, so owner Bob French designed his own snow-making equipment purported to make snow at thirty-eight degrees, nine degrees higher than traditional snow-making systems.

Ski the Rim was outfitted for night skiing, with ski lessons available under the lights. As with many of the other nearby ski facilities, Ski the Rim had a variety of shortcomings. In addition to uncertain snowfall, the area lacked a paved entrance road and did not have a large enough warming hut.

Over the years, enthusiasm for winter sports ran high in Lake Arrowhead, and it was one of the foremost destinations for Southern California ski enthusiasts. But at an elevation of approximately 5,100 feet, its ski slopes were often showered with raindrops rather than snowflakes. Eventually, skiers knew they could count on snow at higher elevations near Snow Valley or a number of Big Bear Lake areas, leaving Lake Arrowhead devoid of winter sports facilities.