Chapter 3

BIG BEAR LAKE

SLING LIFT/LYNN LIFT/SNOW FOREST

Big Bear’s first ski tow, a sling lift, was built in 1938 and was one of three of the nation’s first overhead cable lifts.26 Most winter sports locations around the country, if they had any mechanical lift at all, had rope tows. Rope tows were difficult and tiring to use, prompting a variety of other designs and methods for uphill transportation. The unique overhead cables took the place of waist-height ropes.

Judge Clifford Lynn, who is most well known for his role in the construction of Big Bear Lake’s first chairlift in 1949, was also responsible for the creation of the sling lift. Lynn was well acquainted with Big Bear winters. In March 1913, while a caretaker at Pine Knot, he snowshoed out of Bear Valley after three feet of new snow had fallen over sixteen hours.27 He went on to found the Big Bear Lake Park District in 1934, signaling the beginning of organized winter sports promotion for Big Bear Valley.

Prior to the construction of the sling lift, ski jumping reigned as the king of winter sports in Big Bear Lake and throughout Southern California mountains. In fact, the first Special Use Permit that Lynn applied for and received on December 22, 1937, was to “construct and maintain a ski jump.”28 But Lynn and Tommi Tyndall, founder and developer of Snow Summit, would later be most influential in guiding Big Bear Valley from the ski jumping era to the alpine era.

Less than a year after receiving the Special Use Permit for a ski jump, Lynn applied for a second Special Use Permit on October 6, 1938. This permit included construction of a ski tow, ski hut, chemical toilet and power plant shed. It was approved on November 2, 1938, and work on the tow began immediately. Lake Arrowhead ski pioneer Edi Jaun erected the towers for the 1,200-foot sling lift.29 The Mountaineer reported that the location would be “one of the finest ski fields in the mountains,” but the Big Bear Lake Park District was still formulating a plan to get skiers from the center of town to the area.30 If the road to the area proved too difficult, skiers could be transported from Pine Knot and Big Bear Boulevard in Sid Sutherland’s weasel.

Donald Dawson designed the Big Bear sling lift, a jig-back affair, and fashioned it after the Fish Camp (Snow Valley) tow, also built in 1938. The sling lift carried a series of ten slings on each side ending in triangular grips hanging from an overhead cable suspended about ten feet off the ground. In spite of stationary loading, boarding the tow was cumbersome.

Skiers waited in line at the bottom of the hill, standing next to two rows of twelve stakes each. When the empty slings came to a stop, one sling sat next to each stake. Once the slings were in place, the skiers stepped into position and hooked their ski poles into little clips, grasped the triangular slings with both hands and waited. When all ten skiers were ready, the operator started the lift. The skiers were pulled uphill as long as they kept hanging onto the sling. Empty slings came down on the other side.

Big Bear Lake’s sling lift, one of three built in Southern California. The others were at Lake Arrowhead and Fish Camp (Snow Valley). Photo by Elmar Baxter.

The lift moved along at three to four miles per hour. If someone fell, which was a common occurrence, the operator stopped the lift until the skier was on his feet. The lift then started again. When the skiers reached the top of the run, the lift stopped to let them unload. At the same time, skiers at the bottom of the hill were hooking up. The direction of the cable reversed, and the cycle repeated.

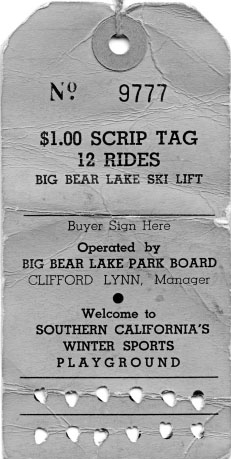

A tow ticket for Big Bear Lake’s first ski tow, a sling lift. Clifford Lynn received the Special Use Permit in November 1938, and the tow began operating shortly thereafter. Skiers accustomed to strenuous uphill climbing to earn their downhill runs were more than happy to pay for an easy and fast ride to the top.

Dick Kun, chief executive officer of Big Bear Mountain Resorts, remembered riding the lift as a ten-year-old: “I hung on to that trapeze ring for dear life. Every time the grip on the haul-rope passed over a sheave on the tower I’d get hoisted a few feet off the ground.”31

Lift capacity was 200 persons per hour;32 12 skiers were carried up the hill every two and a quarter minutes.33 Some of today’s lifts carry 3,600 skiers per hour, but skiers were more than happy to catch a ride on the old sling lift, a workhorse for more than twenty years. On one busy weekend in 1947, three thousand rides were sold.

Frank Moore, Redlands historian and former editor of the Redlands Daily Facts, gave a detailed description of the sling lift to the Sierra Club Ski Mountaineers:

The tow will be located about  mi. from the business center of Pine Knot. The altitude at the bottom is 7000’, and the run is a dip profile, steeper at the top, 1070 feet long, with a rise of 225 ft. The time for a trip from bottom to top is estimated to be 1

mi. from the business center of Pine Knot. The altitude at the bottom is 7000’, and the run is a dip profile, steeper at the top, 1070 feet long, with a rise of 225 ft. The time for a trip from bottom to top is estimated to be 1 minutes. No definite charge for tow rides has been set; built by the Big Bear Park Dist. from public monies, it will be operated on a non-profit basis. Technicalities of possible interest to Up-Ski Engineers are: there are 8 steel towers set in concrete, 14ft. high and 8-ft. crossarms; 10” ball bearing sheaves and

minutes. No definite charge for tow rides has been set; built by the Big Bear Park Dist. from public monies, it will be operated on a non-profit basis. Technicalities of possible interest to Up-Ski Engineers are: there are 8 steel towers set in concrete, 14ft. high and 8-ft. crossarms; 10” ball bearing sheaves and  ” -6 strand plow steel cable. Power is furnished by a Ford V8 motor.34

” -6 strand plow steel cable. Power is furnished by a Ford V8 motor.34

From these modest beginnings, Big Bear Lake eventually grew from a summer-only resort to the winter sports capital of Southern California. In the mid-1940s, the Grizzly reported, “Big Bear has long been the vacation mecca for thousands of Southern Californians who enjoy mountain outings and lake fishing and water sports; but more and more the valley is coming into its own as a winterland of vacation thrills.”35 But as late as 1947, Big Bear was described as “really a summer resort, with only a few of the motels and hotels bothering to stay open during the winter. Season is January through March. Only upski of any importance is behind the town of Big Bear itself, and is a compensating saddle type lift like Snow Valley’s. Bill Munson operates a rope tow at Bear City, just a few miles beyond Big Bear Lake higher in the mountains.”36

However, it was also in 1947 that the community of Big Bear finally began to equip itself for its role as the winter sports capital of Southern California. The Winter Sports Committee of the Big Bear Lake Chamber of Commerce attempted to secure a certified instructor from the California Ski Association. The committee also began to campaign actively to attract intercollegiate ski teams and clubs in the California Ski Association to hold their meets in Big Bear Valley.

Coincidentally, Tommi Tyndall, founder of Snow Summit in 1952, came to Big Bear Lake in 1947–48. The Chamber of Commerce needed to look no further for an instructor. Tyndall arrived in Big Bear already experienced in ski instruction and ski school development. He taught in Sun Valley’s ski school and had started ski schools at Cannon Mountain, New Hampshire, and Wilmot Hills, Wisconsin. He established ski schools at the sling lift and the Lynn chairlift, which he used as his center of operations. He founded the Big Bear Winter Club, which held its first Snow Carnival in 1949. He consolidated his Big Bear Lake ski schools in 1948 and ran them under the name Mill Creek Ski Schools. In January 1949, he changed the name to Big Bear Certified Ski School. In addition to the Lynn Lift, the ski schools operated at the Mill Creek Ski Bowls, Moonridge, the Sugar Loaf area and the Swiss Ski Tow.37

Big Bear Lake’s first chairlift, the Lynn Lift, was built in 1949. The only other chairlifts operating in Southern California at this time were the Mount Waterman chair, built in 1942; the Blue Ridge chairlift, built in 1947; and the recently completed chairlift at Snow Valley. All four were single chairs.

Judge Lynn, former chairman of the Big Bear Lake Park District, was the moving force behind the lift. The three-thousand-foot chair was located near the sling lift area on the slopes a few hundred yards south of the village. It had sixty chairs and a seven-hundred-foot rise. The ride took about ten minutes, and 240 skiers could be whisked to the top of the hill every hour.

Lynn worked tirelessly to bring about the completion of the chairlift. He originally submitted the application for construction of the lift in September 1940, and it was approved by the Forest Service on October 7, 1940. Had construction gone forward at this time, it would have been Southern California’s first chairlift. A cumulative tax fund had been set aside to finance the project.

Also in September 1940, Lynn submitted two different sets of chairlift plans to the Forest Service. Hoping to expedite approval and the bid process, one of the plans he submitted was for a chairlift similar in design to one that had already been approved by the Forest Service in Bishop. He expressed a desire to have both plans approved, stating that “the Big Bear Lake Park District Board would ask for bids on both the original and alternate plans and would undoubtedly accept the lowest bid.”38

The first set of plans was for a traveling cable–type lift, whereas the second set of plans was for a trolley-type lift. The Forest Service approved the plans for the traveling cable–type lift, but both designs were fraught with problems. Discussing the trolley lift, C.B. Morse, assistant regional forester, wrote, “We are glad the Big Bear Lake Park District officials have abandoned the idea of using this particular design. The plans submitted are entirely inadequate and considerable engineering work would be required by them, in working up satisfactory details.”39

After approval of the traveling cable–type lift, bids for construction were opened on October 10, 1940. But there continued to be ongoing discussion between the State Division of Engineering, the Forest Service and the Big Bear Lake Park District Board regarding the design and safety of the chairlift.

At this time, Sugar Bowl operated the only chairlift in California. The design for the Lynn Lift was similar to the Mount Hood chairlift, so the Division of Engineering was basing the feasibility, performance and safety of the chairlift on that design.

The rudimentary era of chairlift design is evidenced by concerns expressed by the Division of Engineering: “We are not familiar with this type of lift and have never seen one in operation. Due to patents on the chair, it is not possible for the contractor to furnish several pertinent points in operation. Thus it is possible that some of our basic load assumptions might be too great, but we have tried to give the benefit of the doubt to the design.”40

Once design and safety features were deemed satisfactory, approval to begin construction was given on October 24, 1940. But a problem of a different sort delayed construction. In November 1940, the state attorney general ruled against construction because

the law states that such a park district can not construct improvements on land outside the boundaries of such a district. There is a clause in the law, however, that states in effect that if such improvements serve the general public as a whole and can not be located within the district, an exception may be made. It is now planned that the Big Bear Park District secure the aid of State Senator Swing in securing special dispensation in this particular case through the State Legislature. Therefore, action on this particular case will be held in abeyance until legislative action succeeds or fails.41

Then, when World War II began, plans came to a standstill. The Forest Service notified the park board that the Special Use Permit “could not be used until postwar conditions made it possible for the district to erect the structure anticipated and approved in your lease papers.”42

The prewar estimate for the cost of lift construction was between $15,000 and $18,000. In the early days of the war, money was available for the project, but the price of steel skyrocketed during the war. At least $25,000 would be required to fund the project. Then the availability of steel and materials was restricted, and prices continued to spiral higher and higher. By the time the war was over, the cost had ballooned to $48,000.

In June 1948, Lynn renewed his efforts to get chairlift construction started. The Park Board had $45,000 available, but bids were twice that amount. Not to be deterred, Lynn began contacting local firms regarding the project. Dick Cannon, engineer for Coast Builders in Santa Monica, assured Lynn the lift could be built with the funds available.

September 24, 1949, marked the formal dedication of the chairlift. The ceremony also served as somewhat of a memorial to Lynn. In April 1949, the Big Bear Winter Club hosted a contest to name Big Bear’s first chairlift. The contest was publicized in the San Bernardino Sun and other local newspapers, encouraging a large number of entries. The contest closed on May 15, and the Winter Club hoped to find “a proper name for this area suggesting the beauty and grandeur of the new county chairlift site, and its wonderful slopes and snow conditions.”43 But when Lynn took his own life in August 1949, the lift was named in his memory.44

District commissioners, county officials and members of the press were on hand for the historic event. Local residents were invited and given free rides on the lift. The magnitude of Lynn’s contribution to Big Bear Lake winter sports was conveyed in the dedication speech:

Gene Merwin (left), designer of the Lynn Lift, with lift engineer Dick Cannon. The Lynn Lift was Big Bear Lake’s first chairlift and the fourth in Southern California. Southern California’s first three chairlifts were built at Mount Waterman, Blue Ridge and Snow Valley. Photo by Wolfgang Lert.

The Lynn Lift opened to much fanfare on September 24, 1949. Bill Kingsley, president of the Big Bear Lake Park Board, takes a ceremonial ride on the historic day. Photo by Wolfgang Lert.

Clifford Roy Lynn dedicated his life and services securing realization of his dreams, of his vision to make Big Bear a winter sports field second to none. He worked unceasingly—often in a single handed battle against great odds—because of his conviction that winter sports at Big Bear could be the finest in the west if proper facilities were made available to the public…Today it is just and fitting that we dedicate the Clifford Lynn Chair Lift to the memory of one who visioned for Big Bear leadership as the winter sports center of the west, and took upon himself the obligation of securing the means to that end.45

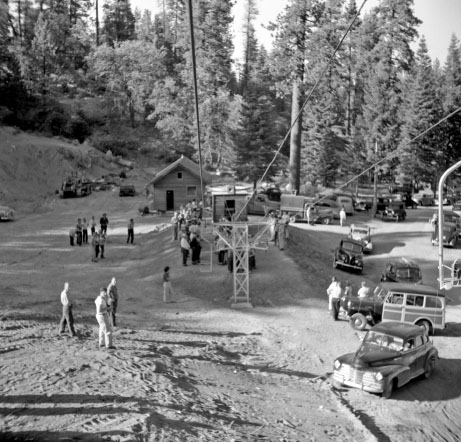

A view of the Lynn Lift base area on opening day, September 24, 1949. Photo by Wolfgang Lert.

At the time of its completion, it was one of fewer than ten chairlifts in the nation and operated in both winter and summer. Tyndall’s Big Bear Winter Club enthusiastically began promoting all of Big Bear’s ski tows and all manner of winter sports. The club created a postcard, the front showing Tyndall’s map of the local winter sports areas and the verso giving a vivid description of the Big Bear winter sports scene:

Here are the “bear” facts about the new chairlift at Big Bear. What a deal! Park-Board operated—carrying 240 skiers per hour…up over beautiful snow to almost 8000 ft. elevation. Skiers from all over Southern California are thrilled. Beginners learn in ski school on broad, easy slopes at the top. Experts schuss and swoop on steep, exciting runs all the way down. What’s more, there are 8 other good ski areas in Big Bear now (see map)—plus a dozen tows including the familiar sling lift on “Old County.” No other area around offers such a variety of winter sports so close to a community of 7000 pop. We sponsor tobogganing, movies, ice skating, bowling, and dancing. All this and accommodations too! So many resorts, lodges, hotels, cafes, and bars it’s hard to choose. Plus regular bus transportation—Mt. Auto Lines, Tanner Motors, and Greyhound. This is the place. Come up and “ski” for yourself…only 3 hours drive from Los Angeles—4 from San Diego. Hitch hike if you have to. It’s worth it. See you soon…46

The inaugural season was a great success but was not without some problems. On October 30, 1949, the cable dropped off the sheaves at tower nine, dropping six passengers to the snowless ground. Miraculously, only one of the riders was injured. The chair she was riding was demolished.

Because of this accident, the Lynn Lift was inspected in July 1950 by the Engineering Department of the Pacific Indemnity Company. Its report was severe. It stated:

Close investigation now indicates the fact that the pulley wheels are splitting the axles. From all indications, there is a great deal of vibration set up in the pulley constellations when the chair lift clamps pass through these pulleys. This vibration, coupled with the heavy cable stress, is bound to continually break out at some point, with the constant possibility of riders becoming injured through failure at one of these points.

It is my considered opinion that a major overhaul of the entire set-up along the following lines will be necessary before it can be considered a safe, standard chair lift:

1. A re-survey of the profile should be made and some of the towers placed in a different location in order to flatten out the cable travel and eliminate some of the stresses which it now develops.

2. Towers should be anchored more firmly and X-braced with angle iron, rather that flat strap iron.

3. They should use one of the standard pulley arrangements which would eliminate some of the vibration caused by the present cable clamps.

4. The towers should be screened or shielded on the one side to eliminate the possibility of the skis getting hooked into them.

5. A guide should be installed around the No. 1 tower and motor house to prevent the chairs from smashing into the building.47

In September 1950, the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors approved the use of $5,000 for the required repairs. D.W. Kingsley, chairman of the Big Bear Lake Park Board, explained that with the appointment of Bill Franklin and Don Dawson to the park board commission,

the county feels that the district is now in an excellent position to manage the lift. The board now has engineering ability, mechanical ability, and funds. Mr. Franklin engineered the original plans for a chair lift at Big Bear. However, they were never used because the engineering called for a project more costly than the district felt it could undertake, but they have subsequently been endorsed as the only feasible chair lift plans by such authorities as noted chair lift construction firms.48

The other major problem was access to and parking at the area. The completion of the Lynn Lift resulted in an influx of winter sports visitors, and road conditions to the area were narrow, steep and dangerous. To alleviate the parking problem, the Big Bear Lake Park Board issued a request to the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors to purchase the “area comprising Lots 43-44-46-47 and 48, Pine Knot Subdivision No. 2…by condemnation if necessary, also, of the donated easement consisting of a fifty (50) foot wide right of way, a continuation of Pine Knot Boulevard extending from Oak Street south to Cameron Drive, approximately 1500 feet in length.”49 This plan would have accommodated four hundred cars within a five-hundred-foot radius of the chairlift and would have served skiers using both the chairlift and the sling lift.

Local residents objected to this proposal, so the plan never gained approval from the Board of Supervisors. In March 1951, the Park Board requested permission to purchase two acres of land from W.A. Dermid for the purpose of developing a parking area at the Lynn Lift.

A winter view of the Lynn Lift. The historic single chair operated for more than thirty years until it was finally removed in 1981.

The popularity of the lift continued to grow over the years and led to long lift lines on busy weekends, with skiers sometimes enduring a forty-minute wait. In its first three seasons of operation, the lift carried six thousand summer and winter passengers. The lift also benefited local businesses, with some businesses reporting that income tripled after the lift went into operation.

The completion of the chairlift was just the beginning of the development of the area, and improvements continued throughout the 1949–50 season. The Big Bear Winter Club held slope-clearing parties, and after the snow fell, the Park Board realized that it needed an additional tow for beginners. In January 1950, it installed a rope tow for access to the “bunny bowl” at the top of the chairlift. With the seven-hundred-foot rope tow, beginners could ride the chairlift to the bowl, ski the bunny bowl with uphill access via the rope tow and then at the end of the day ride the chairlift back down without having to ski over steep runs lower on the hill. Prior to the installation of the rope tow, beginners were limited to using the sling lift or other beginner tows in the valley, but they now had access to the deep powder that sometimes blanketed the higher slopes.

The Lynn Lift underwent additional upgrades during the 1950–51 season. The Skier described the improvements: “Number two run is now smooth and wide all the way down—a beauty for intermediates starting at nearly 8000 feet and gliding down for over a mile to the chairlift terminal at 7000 feet. ‘Steilhang’ on Number one expert run has also been widened, and at the top of the chair, the contour of the Bunny tow has been changed so the rope rides high and dry.”50

In addition to the upgrades made to the Lynn Lift area, the sling lift slopes also underwent big changes. A road now connected the two areas, which permitted skiers to be transported by weasels from the village. For skiers driving to the area, the access road was improved and parking capacity increased.

Also at this time, Tommi Tyndall and Hank Smith’s Big Bear Certified Ski School became more organized and prominent. A large area at the bottom terminal of the Lynn Lift was cleared and marked specifically for ski school use. They added a Jeep-driven tow that carried beginners up a long, gentle slope. This tow was installed for the exclusive use of the ski school. And for the first time, the Park Board and the Big Bear Certified Ski School signed a contract, signifying complete cooperation between the two organizations.

As Snow Summit and other Big Bear Lake ski areas were developed in the early to mid-1950s, the Park Board began to have reservations about conducting a business that competed directly with private ski area owners. In a letter dated October 30, 1956, A.P. Tidwell, chairman of the Big Bear Lake Park Board, wrote to the Board of Supervisors asking them to consider the sale of the winter sports facilities operated by the Park District. He explained that private ski area operators “have entered the winter sports field on a large scale in Big Bear Valley, meeting the needs of winter recreation enthusiasts of Southern California,” and that “it is not in the best interest of the community to continue to operate winter sports facilities in competition with private enterprises.” He went on to explain that the Lynn Lift area had “fulfilled its original function of fostering growth of winter sports facilities in Big Bear Valley.”

This was not the first time local ski tow operators voiced concern over unfair competition with the county-owned Lynn Lift. In a 1950 letter to the County Park Board, a group of ski area operators wrote:

We, the undersigned, owners of private ski tows, vigorously protest the use of taxpayer’s funds for this purpose [construction of a new rope tow]. We believe that any further investment of County funds in competition to us is a decided infringement upon our rights and the rights and privileges of private enterprise and management. We, endeavoring to earn a living in a field already practically monopolized by the County Park Board, are directly competing with a business subsidized by the monies paid by us and other taxpayers of Bear Valley.

While we independent ski tow operators must depend on our actual earnings to exist and to make improvements upon our investments, the County facilities may pour more funds into improvements each year, without having earned these funds. If this continues, it is inevitable that private industry will be forced out of the ski tow business in Bear Valley.51

The letter was signed by John Sipe, Upper and Lower Mill Creek Ski Bowls; Virgil Foust, Swiss Ski Tows; Max Files, Lone Star Ski Tow; and Bill Goold, Snow White Ski Tow.

The county put the area on the auction block on May 28, 1957. The Park Board recommended a minimum bid of $125,000.52 No bids were received and Forest Service officials suspected two reasons: the lack of snow the previous year and spring being the wrong time of the year to try to sell a winter sports area.

A second attempt to sell the area was initiated on October 2, 1962. The County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to authorize the Big Bear Lake Park Board to call for bids for the sale of the area. The minimum bid was set at $75,000.

The county continued to own and operate the lift through the end of 1962. Then, in January 1963, Edward Blacker and J. Edwin Spangler, the sole bidders, acquired the area for $75,000. Spangler had owned and operated his own businesses and had experience managing more than 150 employees. Blacker was a partner in the Black & Blacker real estate firm in Pasadena, where he had been a successful broker for more than thirty-two years.

Immediately after the purchase, Blacker and Spangler applied for incorporation under the name of EBES Enterprises, Inc. However, in March, completion of the sale was delayed for thirty days because the pair was waiting for the approval of the Securities and Exchange Commission to sell stock. Then, in early April, the pair backed out of the deal, claiming that financing fell through because of “death, sickness and poor snow conditions.”53

Brothers Dave and Dan Platus became the new owners in April 1963 and renamed it Snow Forest. Snow Forest was made up of two separate and distinct areas. The lower portion, the Lynn Lift area, was outfitted with the single chairlift, one rope tow, a cafeteria, ski rentals, a ski shop and a ski school. Facilities at the upper area, known as Little Siberia, included four rope tows, a snack bar, ski rentals, a ski shop and a ski school.

The brothers immediately began making improvements. Snow making was first on the list, and by December 1963, a snow-making system was in place on Little Siberia and the twenty-five-year-old sling lift was replaced with a rope tow. Because of their new snow-making system, the 1963–64 season was expanded to ninety-four days, more than doubling a typical season without snow making.

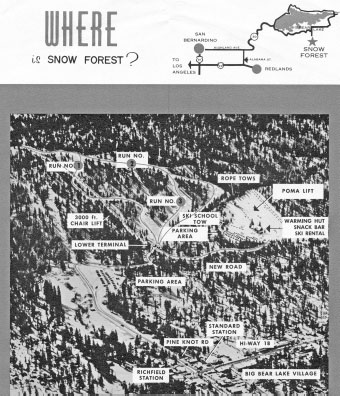

A map of Snow Forest showing how two distinct areas were fashioned into one. The area to the right had been known as Little Siberia, while the other area was simply known as the Lynn Lift.

In spite of increased skier days, Snow Forest was in the red by the end of the Platuses’ second season at the helm. Forest Service officer D.M. Tucker spelled out the difficulties Snow Forest faced:

The cold truth, as I see it, is that at present this area is hard to find, hard to see, and the slopes much less attractive than Snow Summit. Due to County operation, with no competitive incentive, the permittee is faced with a job of attracting customers away from Snow Valley, Snow Summit, and Moonridge. This will require 3–5 years to attract customers through a bold advertising campaign. Next, improvements and slopes must be competitive with other winter sports areas. Increasing interest in skiing may help this situation. Investors will have to wait for 3–5 years before a return can be expected.54

Snow Forest acquired additional acreage next to Little Siberia and was in a position to undertake significant improvements to the area prior to the 1967–68 season. But in March 1967, the Forest Service began to push for the removal of the Lynn Lift because of considerable erosion problems on the slopes served by the chairlift. This became a point of contention between the Forest Service and Snow Forest. Dan Platus wrote:

It has been concluded by Snow Forest, Inc. that expansion of its Siberia area with the installation of a major lift facility accessible from the main highway entering Big Bear Lake Village represents the most expedient means of developing Snow Forest into a competitive winter sports area. Further development of its existing Lynn Chairlift area will require reevaluation pending some operating experience with the expanded Siberia area.55

The Forest Service, however, did not want the development of any new facilities on Little Siberia and the adjacent 160 acres until the Lynn Lift was removed. The Platuses felt that the Lynn Lift was too important to their business to remove it in the three to five years recommended by the Forest Service. They wanted to develop Little Siberia before the removal of the Lynn Lift. In a letter to the district ranger, Dan Platus spelled out Snow Forest’s position:

The immediate objective of Snow Forest, Inc. is to conduct a profitable or at least self-sustaining winter sports operation while providing an important service needed by the National Forest using public. It is believed that this may be possible with the existing facilities either in their present condition, or with perhaps some limited improvement to the Little Siberia Area such as the addition of a Poma or platter lift on the existing ski slope. While it is our ultimate objective to consolidate the operation on the Little Siberia Area, we must rely on existing facilities until such time that they are not needed. It is most certain that the present operation could not be sustained without the existing Lynn Chairlift…Based on the operation on natural snow during the past two seasons, the chairlift accounted for 45.5% and 49.9%, respectively, of the total revenue from lift and tow tickets. In the event that the chairlift were not operated, the total yearly operating cost would be reduced very little, yet this major source of revenue would be eliminated.56

After several written exchanges and meetings, a new Special Use Permit was agreed upon on October 23, 1967, and Snow Forest was able to complete the installation of a new one-thousand-foot Poma lift at Little Siberia in time for the 1967–68 season.

But money woes continued to plague the business. In September 1968, the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors decided to foreclose on Snow Forest. The brothers had not kept up with payments or paid taxes on the area. However, two months later, the board voted to allow the brothers to operate for the coming winter while financial difficulties were being worked out.

Snow Forest survived the foreclosure threat, and in January 1970, a Development Plan and Program was submitted to the Forest Service. The installation of Chairlift No. 2 during the 1970–71 season was of the utmost importance to Snow Forest management. That chairlift would have served the entire Little Siberia bowl, and Dan Platus explained, “We are undertaking this project at a time when the economic climate places great financial burden on each Snow Forest shareholder. The risks are required however because this development is so essential to the basic objective of attaining a financially profitable operation while at the same time providing a good public service.”57

In April 1972, the Board of Directors of Snow Forest, Inc. decided to put the area up for sale. They concluded that they did not have the capital necessary to develop the area into a self-sustaining or profitable business. The Platuses continued to operate the area, and during the 1972–73 season, the old Lynn Lift suffered several accidents, structural failures and malfunctions. It is remarkable that the Lynn Lift was still in operation. As early as June 1957, Jack Kilsky of the Division of Industrial Safety noted that the “chair lift was in bad condition and would need to be replaced next year.”58

The problems with the lift forced Snow Forest to request non-use for the 1973–74 season. They were not able to make the necessary upgrades to the lift and felt that too much revenue would be lost without its operation. Snow Forest remained closed through the 1976–77 season. The owners had invested a substantial amount of money in the area over the years, and efforts to secure a buyer for the area continued even while the tows and chairlift sat idle.

In September 1977, Ken Lieb, a longtime skier and certified public accountant, purchased Snow Forest. Then, in November 1977, he purchased nearby Magic Mountain, with plans to combine the two areas into one 190-acre area called Crystal Ridge Ski Area. He served as president of the Crystal Ridge Corporation, established in July 1977. In addition to Lieb, stockholders included Arnold Snitser, Carole Evans, Pete Pecarovich, Wilbur Petrick, Howard Jenkins III, Frank Genova and Robert Brown.

Lieb had extensive plans for his new area. The old lifts were to be removed and replaced with five chairlifts, one Poma lift and two rope tows. An extensive snow-making system was included in the plan, as well as increased parking and base lodge facilities. One of the proposed lifts extended beyond the permit boundary, which would add an additional twenty acres to the Snow Forest area.

In July 1978, as negotiations for Snow Forest continued, Lieb made plans to install two portable Poma lifts and two rope tows on the property at Magic Mountain and did not plan to open Crystal Ridge until the 1978–79 ski season. He was awaiting the completion of the Special Use Permit for Crystal Ridge and permission to install a snow-making pond. The Forest Service doubted that Lieb could meet the financial requirements of his Special Use Permit since the Small Business Administration declined his loan request and a source of additional financing fell through.

The negotiations for the sale of Snow Forest to Crystal Ridge were terminated in August 1978, but Lieb was still interested in obtaining the permit for Snow Forest, pending proof of his financial ability to operate and develop the area with mutually acceptable terms with Snow Forest, Inc.

However, the Forest Service still had doubts about Lieb’s plans and his ability to bankroll those plans. The acting forest supervisor wrote, “There continues to be a question as to whether Crystal Ridge can qualify financially for a Special Use Permit. If not, Snow Forest is anxious to place their facilities back on the market, if a permit is not forthcoming to Crystal Ridge.”59 After review, the Forest Service concluded that it saw “no positive indications that the corporation would be able to handle the proposed development cost of approximately $750,000.”60

During the fall of 1979, the U.S. Forest Service issued an edict for the Platus brothers to either revive Snow Forest or forfeit their permit, so they reopened for the 1979–80 season. Three factors influenced their decision to open the area: “A very favorable arrangement with the forest service as well as increased financial backing; needed room to expand and a tremendous increase in the number of ski enthusiasts.”61

The area opened without the use of the Lynn Lift because of the chairlift’s age and poor condition. The initial cost of start-up was small because existing facilities could be remodeled rather than having to build new structures from scratch.

The Platus brothers continued as owners and operators and, in 1980, acquired a new business partner, Bob Boothe. Catering to the novice skier, the owners advertised Little Siberia as a “10-acre ski hill serviced by a 1000-foot long Poma lift, three rope tows, 100 percent snowmaking, and 100 percent snow grooming. All runs are geared for learning skiers; no schussboomers or competing with advanced or expert skiers.”62

Boothe acted as general manager until he bought the area from the brothers later that season. He also purchased the adjacent Crystal Ridge area. Finally, in 1981, the thirty-two-year-old Lynn Lift was removed and was later replaced with a new three-thousand-foot-long triple chairlift with a six-hundred-foot vertical rise. The triple chair, which debuted on January 6, 1982, had an uphill capacity of 1,800 skiers per hour.

When Snow Forest opened for the 1981–82 season, it was actually three areas in one. The new triple chair provided access for the Lynn Lift hill; a Poma lift and three rope tows served Little Siberia; and a platter tow and two rope tows operated on the slopes of Crystal Ridge. The entire area now had a two-thousand-skier capacity.

Dave and Dan Platus bought the Lynn Lift area in April 1963 and named it Snow Forest. Once the Lynn Lift was removed, construction began on a triple chair. A helicopter was indispensable in transporting and placing lift towers. The triple chair opened on January 6, 1982. The old Lynn Lift had an uphill capacity of 240 skiers per hour. The new triple chair carried 1,800 skiers per hour. Courtesy of Ray Ransom.

Snow Forest underwent significant improvements for the 1983–84 season. Prior to this time, the chairlift only serviced runs designed for advanced skiers. The Lynn Mountain run was only twenty feet wide but was widened to three hundred feet. Fifteen acres of new terrain were added to the area, and major upgrading took place on some of the existing runs. Because of the extensive improvements, Snow Forest was named the Far West Ski Association’s “Outstanding Ski Area of the Year” for 1984. It was also given the Tommi Tyndall award for making a distinguished contribution to skiing.

Snow Forest was an ideal area for beginners. Advanced skiers seeking more challenging terrain passed it by. The longest run was only three-quarters of a mile, the vertical drop just eight hundred feet. At one time, owners hoped that Snow Forest could be developed so that they could compete with nearby Snow Summit and Goldmine. But in its more than forty-year history, the Lynn Lift–Snow Forest area seldom operated in the black. Don R. Bauer, forest supervisor, summarized the difficulties that Snow Forest faced:

Through the years with the development of other winter sites on nearby National Forest and private lands, the old Lynn lift and its successor Snow Forest, Inc. have been unable to remain competitive in this highly competitive field, and at the same time fulfill the terms of the special use permit agreement. A clear cut public need for the expanded facilities as proposed by Snow Forest Inc. no longer exists in this area. Superior opportunities for expansion of “high lift ski operations” exist nearby. Both Snow Summit and Moonridge areas are capable of and have plans for expansion in addition to new areas which can be developed should the public need and availability of private investment capital warrant.63

Snow Forest closed permanently in 1992.

Even after the area closed, the Forest Service continued to receive inquiries about reviving the area. Its fate was officially sealed in 1993. According to Paul Bennett, U.S. Forest Service district winter sports administrator, “The district has had various inquiries regarding the possible reissuance of a Special Use Permit for the area. However, at this time I believe there is no need to provide additional skiing and snowboarding opportunities for the public in the Big Bear area.”64

Bennett felt that the area, if revived, would not be economically viable. The area had a long history of financial troubles and over the years had been on the edge of financial collapse. Bob Boothe, who was the last permittee for the area, had filed for personal and corporate bankruptcy.

During the 1990s, all of the buildings, along with the chairlift and rope tows, were removed from the site. The former slopes that once were home to the unique sling lift and Big Bear Lake’s first chairlift now sit empty and barren. And even though the ski tows last carried skiers up the historic hill twenty years ago, in 2006, the Forest Service was still confronting substantial erosion issues at the area.

REBEL RIDGE

Chuck Smith founded Rebel Ridge in the fall of 1955, and in a January 1956 ski column in the Los Angeles Times, Glen Binford referred to Rebel Ridge as “a really hustling, comparatively new spot just beyond Big Bear.”65 Smith had worked for Tommi Tyndall at Snow Summit, but the two did not always see eye to eye. Their disagreements led Smith to name his area “Rebel Ridge.” He chose an area located on a small north-facing ridge on the west boundary of Big Bear City. By its second year of operation, Rebel Ridge was the only Big Bear area offering night skiing, available on Friday and Saturday nights. Smith operated four rope tows serving five acres of clear, open slopes: one 1,500-foot, two 900-foot and one 600-foot beginner tow. The area was also outfitted with two toboggan runs and a warming hut.

The resort was unique in that the slopes were carefully bulldozed for each class of skier, up to advanced intermediates. They were arranged so each class of skier skied within his or her own boundaries, eliminating the schussboomer traffic from the top of the hill into the beginners’ area. Ed Heath, brother of 1936 Olympian Clarita Heath Bright, helped Smith lay out the terrain. Heath, hired on as the ski school director, felt Rebel Ridge had one of the top teaching areas in Southern California.

Smith experimented with snow making at Rebel Ridge as early as 1956.66 In his first attempt, he hoped to cover an area one hundred by eight hundred feet with eight inches of snow. He installed two-inch water mains and used a hose borrowed from the local fire department.

Through the New Year weekend of the 1960–61 season, Rebel Ridge was the only ski area open west of the Mississippi.67 Daytime temperatures were balmy, but nighttime temperatures sometimes dropped lower than twenty-eight degrees, the temperature that Smith calculated to be the magic number for snow making. On those occasions, he kept his pumps, pipes and nozzles running all night. The dry, pine-covered hills became blanketed with snow. Four to six inches of fresh, natural powder blanketed the man-made base that had been sprayed on the slopes previously. His system was large enough to keep two runs open.

Skiers knew where to find the only snow in Southern California, and their cars filled the parking lot. The two nine-hundred-foot rope tows carried the snow-starved skiers to the top of the hill. Neither of the runs was especially long (a little less than a quarter mile) or steep, but these New Year’s skiers were thrilled just to find some snow. Skiing magazine gave an apt description of the Rebel Ridge scene during those early snow-making years: “In the dusty parking lot, two girls in Bermuda shorts and short-sleeved shirts posed for pictures in a 70-degree sun. The background: A snow-covered slope 100 yards away.”68

Prior to the advent of snow making, Rebel Ridge had averaged fewer than thirty days per season, but now it could provide skiing from November to March. However, Smith’s system was labor intensive. Each sprinkler sprayed snow over approximately one hundred square feet, so he and his crew were busy all night moving hoses and sprinklers. But Smith said, “It’s worth it when you take the first run of the morning through that powder.”69

Though others in the West had experimented with snow making prior to this time (Les Salm in the Lake Arrowhead area in the 1940s and Smith at Moonridge in the mid-1950s), Rebel Ridge was the first area in the West to successfully implement snow making, and the “custom snow,” as Smith called it, grabbed the attention of local skiers and ski area operators.70

Snow-covered slopes surrounded by pine needles was a familiar scene at Rebel Ridge in the early 1960s. A pioneer in Southern California snow making, Chuck Smith blanketed the slopes with “custom snow” when nighttime temperatures and conditions permitted. When there was a lack of natural snow, Rebel Ridge was sometimes the only Southland ski area operating thanks to Smith’s man-made snow.

Smith continued to upgrade his snow-making system, and other ski areas took a keen interest. “Rebel Ridge was an eye opener to the benefits of snow making, not only in Southern California but areas in other states as well.”71 Machine snow making guaranteed an early start to the ski season. Areas that had snow making could open in mid-November, while areas without this capability remained idle. Other ski area operators must have known that this could be the answer to Southern California’s fickle weather and sometimes nonexistent snowfall. Tommi Tyndall certainly took notice and installed snow making at Snow Summit by 1964.72

Rebel Ridge’s success with snow making marked a turning point in Southern California ski history. Ski World reported:

1964 may go into the books as the year that technology supplanted wishful thinking as far as local lift and tow operators are concerned. They have decided, almost unanimously, that artificial snow—costly and limited as it is—is the answer to the chronic lack of natural snow. Five of the local ski resorts are introducing snow-making systems this year; two more plan to continue with their existing systems; two are definitely interested but don’t plan anything yet; three are stymied by water shortage.73

Rebel Ridge also underwent a complete face-lift for the 1960–61 season. Slopes were widened and reshaped, tows were relocated and upgraded and a separate area with a toboggan lift was created for non-skiers.

Then, in July 1963, Stu and Liese Hirsh bought Rebel Ridge. They increased snow making by 30 percent and installed a new platter lift on the west side of the area. They added a new rental shop, repair shop, ski shop and the Rebeler Bar and remodeled the restaurant.

In November 1964, the Hirshes invested $50,000 in a brand-new chairlift. This was Big Bear Lake’s third chairlift and second double chair. The 750-foot-long chairlift was equipped with thirty chairs and carried nine hundred skiers per hour. Swiss Freddie Schmutz, well-known ski lift designer and builder, supervised lift construction. The construction of the lift was a joint venture among Schmutz, Allied Cable Ways and American Cable Ways. Skiers now had access to the fourteen-acre area, often covered with “custom snow,” via the comfort of the new chairlift.74

Sepp Benedikter (far right) created an alpine touch to promote his newly purchased Rebel Ridge. Benedikter had been a longtime ski instructor, racer, ski event organizer and ski lift builder. He became a ski area owner and operator when he purchased Rebel Ridge in December 1965.

The Hirshes’ ownership was short-lived. Sepp Benedikter bought the business in December 1965 and immediately began his own rejuvenation of the area. He installed a new rope tow running from the upper terminal of the chairlift to the top, doubling the length of the run. Benedikter also bulldozed a new slope for a slalom course.

When the 1966–67 season began, Rebel Ridge sported a new $50,000 snow-making system. The snow-making system increased from twenty-one guns to thirty. Benedikter noted that the new snow-making system “makes it possible to guarantee a minimum of six inches of powdered snow from Thanksgiving to April.”75

Wanting to attract families to the area, Benedikter created a ski school specifically to cater to families, including lessons for children as young as three. Summing up the focus on families, Benedikter said, “We intend to make Rebel Ridge one of the best family-type skiing resorts in Southern California. And in our advertising and among our contacts, we will emphasize the family specializations we offer.”76

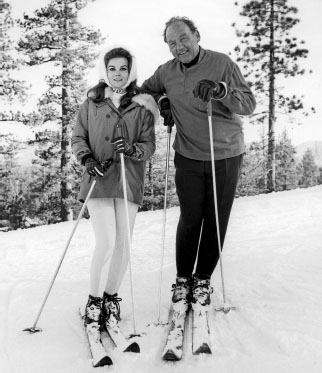

Benedikter began teaching skiing at the age of sixteen in Austria and started a multi-area ski school in Southern California in 1946, serving Blue Ridge, Table Mountain, Mount Waterman and Snow Valley. He was well known among the Hollywood crowd and was often enlisted as an instructor to the stars. Ann Margaret was one of the many stars who signed on for a lesson with Sepp.

An artist’s rendering of the master plan Benedikter hoped to carry out at Rebel Ridge. The proposal included a twenty-room lodge, fifty motel rooms, a one-hundred-bed dorm, a sauna, a pool and a boat dock. His dream was never realized, probably due to lack of capital to invest in the project.

The old site of Rebel Ridge as it looked in the summer of 2011. One of the resort’s original buildings still stands in the parking lot, unused and boarded up. The area now operates as Big Bear Snow Play, outfitted with a modern building and a magic carpet providing easy, uphill transportation for customers.

Benedikter had ambitious plans for the future of the area. His project called for “50 motel units and a 20-room lodge across the highway, with a 100-bed dormitory, sauna baths, a pool with glass sides and sliding roof for year-round use and a boat dock at the lake for guests.”77 Work on the master plan was to begin in the spring. It is not known what stymied the project, but none of the work was ever begun.

Benedikter sold the area in 1969, and the area permanently closed in 1974. After being shuttered for more than twenty years, the area was revived as a snow play and tubing area in 2000. Big Bear Snow Play, with a lone Rebel Ridge building still standing in its parking lot, continued to successfully operate as of winter 2011.

OTHER BIG BEAR LAKE AREAS

The popularity of the Big Bear Lake sling lift was the impetus for others to install ski tows, and in the 1940s and 1950s, rope tows sprung up just about anywhere there was a north-facing slope of sufficient pitch and length.

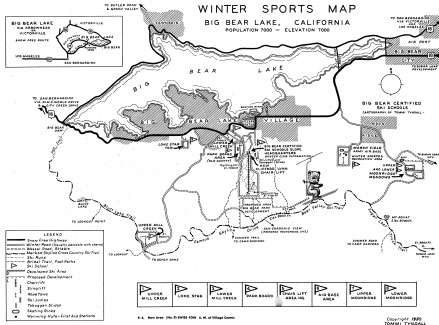

Tommi Tyndall was intimately familiar with Big Bear Lake’s many ski areas, having extensively explored Big Bear’s surrounding mountains. In 1950, Tyndall created this map of the local winter sports areas.

John Webster and John Sipe installed rope tows at Upper and Lower Mill Creek Ski Bowls, probably in 1947. Upper Mill Creek Ski Bowl, located at 8,000 feet, was outfitted with ski tows of 800, 500 and 150 feet.

Webster and Sipe made additional improvements to the two areas in the fall of 1948. They cleared trees and brush from four large trails. At the same time, the Mill Creek Ski Club came into being, directed by W.H. McEwen, John Webster, John Sipe, Tommi Tyndall, Hank Smith, Barney Rief, Johnny Walp, Mary Ellen Webster and Dick Murphy. The club was not a social club; its primary purpose was to promote skiing and all winter sports in Big Bear Valley.

Upper and Lower Mill Creek Ski Bowls were quite popular. While organizing his Mill Creek Ski School in the fall of 1948, Tyndall had high praise for the area: “Mill Creek is not the name of a place. To all good skiers it is synonymous with good snow conditions. The slopes at Mill Creek are famed for having long lasting snow. The name ‘Mill Creek’ is a magic word meaning snow as late as April.”78

Tyndall’s Mill Creek Ski School was unique because skiers could sign up for a week of ski instruction that included “24 hours of actual study, four of which is indoor instruction and the rest on skis. Arrangements for this study will be made to include lodging, meals, and use of ski tows.”79

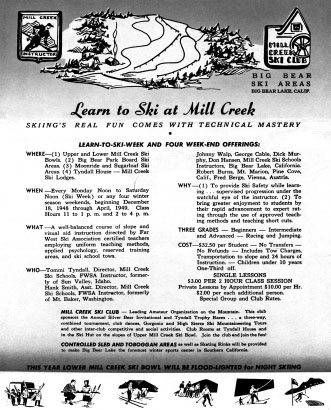

A brochure advertising Mill Creek Ski Area, the Mill Creek Ski Club and Tommy Tyndall’s Mill Creek Ski School, founded in 1948. His ski school served Upper and Lower Mill Creek Ski Bowls, the sling lift and Lynn Lift, Moonridge and Sugarloaf ski areas.

A summer 2011 view of the old Magic Mountain Ski Area. The area originated in 1947 as Lower Mill Creek Ski Bowl, was renamed Little Siberia in the 1950s and in its last incarnation became Magic Mountain Ski Area. Today, the area operates year-round as Alpine Slide at Magic Mountain.

Lower Mill Creek Ski Bowl eventually became Magic Mountain Ski Area. Today, the area, with its double chairlift in operation, is open year-round as Alpine Slide at Magic Mountain.

Ralph Stewart and Virgil Foust built the Swiss Ski Tows near the present Elk’s Lodge. The area was outfitted with two ski tows and a warming hut. Bill Goold operated a tow at what he called Snow White near Coldbrook Camp, with longtime Big Bear Lake instructor Norm Bachelor providing ski instruction. A tow operated at March Air Force Base Recreational Facility, presently the U.S. Marine Corps recreation area. And Max Files’s Lone Star Tow, two miles west of the village where the present-day city hall sits, was equipped with floodlights for night skiing on Friday and Saturday nights. Two tows operated daily, servicing gentle slopes for beginner and intermediate skiers.

In January 1954, a beginner area with two rope tows opened at Stillwell’s, just east of the present-day post office. Stillwell’s, built in 1921 by Carl and Charles Stillwell, was considered the most beautiful lodge in Big Bear Lake. The luxurious pavilion was built of native timber and was situated with an impressive view of the lake. Stillwell’s rope tows, 250 feet and 100 feet long, operated on a gentle slope perfect for beginners. Winter sports visitors also had the use of a warming hut, a toboggan run and ski instruction by John Sipe.

A brochure for Happy Hill Resort, where winter visitors could find a beginners’ rope tow and toboggan and sledding areas.

Hake’s Happy Hill Ski Tow, located in Big Bear near what was then the Lake Drive-in Theatre, operated one tow for beginners and included toboggan and sledding areas.

In the summer of 1948, a $200,000 corporation called Grout Creek Sports, Inc. was formed to create an all-year playground on Grout Creek near Fawnskin.80 Members of the corporation included Jess Wilson, owner of Wilson’s Market in Fawnskin; J.P. McVeigh; Austin Glaze; Ray Kious; and D.W. Gage. The initial master plan for the resort, composed of twenty-six acres near the bridge at Grout Creek, included construction of a recreation center, playground, skating rink, outdoor swimming pool, ski runs, toboggan slides, lodge buildings and clubhouse. The strategy was to bring busloads of college students to the area in both winter and summer at a minimal cost to the students or their colleges—in other words, to do a large volume of business at a small per-person cost.

The original Grout Creek plan was never completed, but by January 1951, a scaled-down Grout Creek Ski and Recreation Area was in business. Manager Jess Wilson oversaw a ski run with a six-hundred-foot rope tow, warming hut, rental equipment, a Scandinavian instructor and food services that offered sandwiches and coffee. Skiers paid one dollar per day, with parking less than three hundred yards away in Fawnskin. The tow was situated five hundred feet from the stone bridge that crossed Grout Creek west of the village and provided access to a variety of ski runs. However, the Grout Creek area experienced limited success, and the operation was short-lived. Unfortunately, Fawnskin, just at the northern fringe of storms, did not receive sufficient snow to sustain a successful winter sports operation, and most skiers were probably frequenting the already established resorts (the Lynn Lift and Moonridge) on the south side of the lake where snowfall was more reliable.

A view of Fawnskin’s six-hundred-foot-long Grout Creek ski tow, March 4, 1951. Courtesy of the National Archives at Riverside, Perris, CA.

The small ski areas throughout Big Bear Valley eventually lost skiers to Snow Summit (founded in 1952) and Moonridge (founded in 1943 and now known as Bear Mountain) as those areas became larger and were outfitted with snow making. Skiers were attracted to the higher, longer and more plentiful runs, taking business from small areas without the capital or acreage to expand. By the mid-1950s, unable to compete, many of the small areas that dotted the slopes around Big Bear were eventually forced to close.