Chapter 4

SAN GABRIEL MOUNTAINS

TABLE MOUNTAIN/SKI SUNRISE

The area known at its inception as Table Mountain Ski Area, later as Ski Sunrise and today as North Pole Tubing Park is three miles west of Wrightwood and approximately seventy-five miles from Los Angeles. The road leading to the area is directly across the street from Mountain High West (formerly Blue Ridge Ski Area). It was one of the few “upside-down” resorts where skiers parked at the top of the mountain and skied down to catch a lift back up. Beginner slopes were at the top near the parking lot. The intermediate and advanced slopes were at the bottom of the area and could not be seen from the parking lot or day lodge.

Winter sports devotees cross-country skied at Table Mountain as early as the 1920s, and after the Smithsonian Institution built a solar research observatory in 1926 along with a dirt access road, the area attracted an increasing number of skiers.

Harlow “Buzz” Dormer obtained the first Forest Service Special Use Permit to construct a ski tow and warming hut on Table Mountain on January 6, 1939. (He applied for the permit on November 15, 1938.) The Big Pines Ski Club was listed as the permittee, in care of Secretary/Treasurer Harlow Dormer. The venture was specified as non-commercial, and the Forest Service stipulated that charges for the use of the tow could not exceed the minimum operating costs.

Dormer began living in Big Pines in 1934 and worked as assistant chief ranger at Big Pines Park for a number of years. He was an avid outdoorsman and one of a group of fourteen skiers who formed the Big Pines Ski Club on January 2, 1932.81 (The club was organized on January 2, but its first meeting was not held until January 9.) The fourteen founding members met at Camp Cienega to work out the details of the club and elect officers. The inaugural officers were Will C. Vaughan, president; Virgil Dahl, vice-president; and Harlow Dormer, secretary and treasurer.

The base area of the Table Mountain rope tow, built in early 1939, the first ski tow in the Big Pines area. Harlow Dormer and Craig Wilson operated the tow for almost five years until Howard More took charge of the area in 1945. Courtesy of Ann Dormer Johnson.

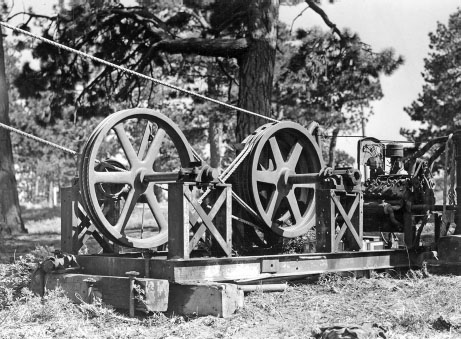

Rope tow motor and gears that powered the Table Mountain rope tow. Courtesy of Ann Dormer Johnson.

Harlow “Buzz” Dormer was an avid outdoorsman and served as the assistant chief ranger for Los Angeles County at Big Pines Park for many years. He and thirteen other skiers formed the Big Pines Ski Club on January 2, 1932. He obtained the first Forest Service Special Use Permit to construct a ski tow and warming hut on Table Mountain on January 6, 1939. Courtesy of Ann Dormer Johnson.

At the club’s second meeting, held on January 16, members planned their weekly ski outing, and President Vaughan appointed Bill Harris as captain of the ski jumping classes and Lester LaVelle as captain of the cross-country and mountaineering activities.

Shortly after arriving in Big Pines, Dormer became the official photographer for Trails Magazine, beginning with the summer 1934 issue. The magazine was published by the Mountain League of Southern California to promote outdoor recreation, especially in Los Angeles County. It was published quarterly, with the autumn issue usually featuring winter sports. Starting with the autumn 1935 issue, a portion of the magazine was designated as the Big Pines Ski Club Year Book. This typically ran only two pages.

The Big Pines Ski Club had hoped to construct a tow at Table Mountain as early as 1936. It published a notice in the autumn 1936 issue of Trails Magazine that it was eager to install a tow on its club grounds. The announcement read, “Feeling the pulse of many of our ski enthusiasts who have but one day a week to ski, and who desire to get in as many rides DOWN the hill as possible in their allotted time, we are attempting to install a power pull-back on the slalom course this winter. We are not promising, but we are pulling.”

The popularity and development of winter sports in the Big Pines area and the immediate success and growth of the Big Pines Ski Club (by 1935, the club had 166 members) were due to the efforts and inspiration of Dormer. Members of the Big Pines Ski Club recognized this, and on December 6, 1940, the club granted Dormer an honorary life membership. He had served as club secretary treasurer from the club’s inception through December 1940, and the club noted that “he has been probably the greatest inspiration in the development of the Club and has generously donated untold time, energy, and personal money toward that development.”82

Dormer and Craig Wilson operated the Table Mountain tow for almost five years until, on December 22, 1944, Dormer filed a request to relinquish his Special Use Permit, handing over the ski tow and warming hut to Howard More.83 More received his Special Use Permit on January 30, 1945, and he didn’t waste any time planning improvements for the area. He wrote the Forest Service on February 8, 1945, explaining his ideas:

A simple advertisement for the Table Mountain Ski Tow.

Within the approval of the Forest Service and other conditions permitting, the writer would like to expand Table Mountain facilities so that there would be at least three tows, and have the area taken in by this Permit enlarged so as to take in the entire Table Mountain Ski area. The writer would also like to be considered primary applicant for the operation of any recreational facilities installed in this area, such as, lunch and shelter installations, etc.84

More, born on August 2, 1914, in Indianapolis, Indiana, spent his youth in Denver, Colorado. He was introduced to skiing through his involvement with the Boy Scouts. Thor Groswold, of the Groswold Ski Company, led Boy Scout ski trips, and it was on one of these trips with Groswold, in 1926, that More strapped on skis for the first time. More made many other ski trips as a Boy Scout and, while attending South High School in Denver, skied with the Rebel Rangers, a group founded by South High chemistry teacher and mountain guide Bob Collier. The club was popular, with seventy-five to one hundred boys and girls involved in climbing, skiing, hiking and other outdoor activities.

More went on to study at the University of Colorado–Boulder, where he earned a degree in mechanical engineering. He later attended Harvard Business School and, in 1939, received a degree in transportation, with a specialization in railroads. More then landed a job with Alcoa, from which he retired after twenty-five years.

Howard More took over operation of the Table Mountain Ski Tow in 1945, marking the beginning of his more than fifty years at the helm. He developed the area into the quintessential family ski area. Renamed Ski Sunrise in 1975, it was purchased by Mountain High Ski Resort in 2004. Mountain High now operates the area as the North Pole Tubing Park.

More eventually moved to Southern California, and one winter weekend in 1941, he drove to Mount Waterman, where at least eight feet of snow had accumulated on Cloudburst Summit. It was on this trip that he discovered Table Mountain.

More’s first season at the helm of Table Mountain Ski Area was in 1945–46. He had experience at other ski areas and had built rope tows at Seven Springs, Snow Valley and Green Valley Lake, but he credited many other men who were instrumental in helping to build and install equipment: Mac Templeton, Frank Jones, Forest Supervisor Bill Mendenhall, District Ranger Charles Beardsley, Cliff Plank and many U.S. Forest Service personnel. Buddy Rowe, Milt Sayle and Elmer Sayle milled the Jeffrey pines into lumber for the day lodge, and Mike Yarborough and Gil Gillard built the massive chimney. Area managers Bob and Erma Waag played a critical role in keeping the operation running smoothly. In the 1950s, Jean Pomagalski traveled from France to install Poma lifts.

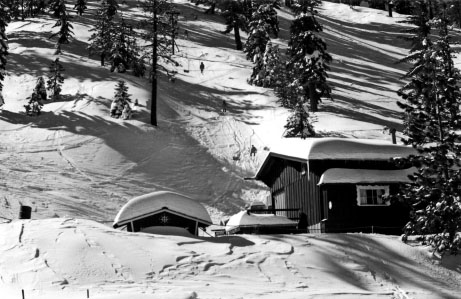

The Table Mountain day lodge shortly after it was constructed. Built during the 1952–53 season, it featured a large outdoor deck with desert and mountain views, a large fireplace, a rental shop and a food and beverage area.

The popularity of Table Mountain Ski Area, especially after World War II, was evident in a note that More sent to the Forest Service in June 1949: “As near as I can calculate, we entertained 6,600 visitors 90% of whom were hauled, mainly by weasel, from the Arch. The road was closed practically the whole season. We operated a total of 40 days (17 weekends) which is some sort of a record for Table Mt.”85

By 1960, Table Mountain skiers could roam the area via two Poma lifts and seven rope tows. One Poma, 2,200 feet long with a vertical rise of 754 feet, was claimed to be California’s largest at the time. The lift served an area with fantastic views of the Mojave Desert. This slope was smoothed into a vast bowl, adding challenging terrain for expert skiers. Intermediate skiers had access to a long ridge and wide, clear trails that led down to the lower terminal of the lift. The other Poma lift, 2,000 feet long with a 350-foot rise, gave access to intermediate and beginner runs.

In 1973, More sold Table Mountain to Tamount, Inc., a group of four investors. Tamount appointed Dave Ward as new general manager of the area, and in 1975, he changed the name of the area to Ski Sunrise. The name was meant to convey a new dawning for the area, which for many years had been overshadowed by Mountain High across the highway.

Ward planned to install a new triple chair, Ski Sunrise’s first chairlift, prior to the 1977–78 season. Workers prepared foundation holes and readied the area for construction, but the lift manufacturer reneged on its promise to deliver all of the lift components by the end of October 1977. Ward finally got his new chair in 1979. Instead of the planned triple chair, he installed a Riblet quad chair. The new lift, 1,550 feet long with a vertical rise of 300 feet, could carry 2,400 skiers per hour.

More foreclosed and regained ownership of the area in 1993. For a number of reasons, Tamount was unable to continue to make payments on its loan. It was also unable to attract the investment capital needed to expand snow making and to make other improvements. After regaining ownership of the area, More’s Table Mountain Ski Lifts, Inc. invested more than $360,000 to refurbish the area. It purchased new equipment, overhauled lifts and improved snow making.

The snow-making system at Ski Sunrise was small, and the lack of snow making eventually took its toll on the area. By early 2001, Ski Sunrise had only been able to open thirty-five days over the previous two years. Skier numbers had dropped from 12,000 during the 1997–98 season to 750 the next. And the success and proximity of Mountain High also had an effect on skier numbers. Bob Roberts, executive director of the California Ski Industry Association, noted that More “had a lack of snow and a lack of capital. He had a cute little lodge but not that much terrain, and he didn’t have the snowmaking. Mountain High became extraordinarily popular, and you can’t play the game when customers are stopping before they get to your doorstep.”86

More owned and operated Ski Sunrise for more than fifty years. In the years leading up to his death on June 10, 2006, he felt it was time for someone younger to take over ownership. In its heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, Ski Sunrise provided families a small and inexpensive place to ski and was often much less crowded than other more popular local areas. But as More became older and less hands-on, the area declined due to a lack of continuity with area managers and insufficient capital investment in the area. Ski Sunrise was really a hobby for More or, as he once described it, his “alter ego career.”87

In November 2004, Mountain High, operating what used to be Holiday Hill and Blue Ridge, purchased Ski Sunrise. The purchase included approximately one hundred acres, with one chairlift and the historic 6,000-square-foot day lodge. Resort owners renamed the area Mountain High North. However, the area remained closed until January 2008, when it was finally able to open after two feet of natural snow blanketed the area. Then, in 2011–12, management renamed it North Pole Tubing Park. It now operates as a snow play area only, laying claim to the largest tubing park in Southern California. When the area is fully operational, there are fourteen tubing lanes and two 450-foot moving carpets to transport tubers to the top of the hill.

A variety of old tow structures and buildings still adorns the slopes at Ski Sunrise. The remains of an old rope tow evoke the area’s historic past.

At North Pole Tubing Park, the classic ski chalet still graces the parking lot, and the old quad chairs hang empty, historical remnants of an area that was home to one of Southern California’s first rope tows and a longtime family-owned ski resort that served generations of Southland skiers.

KRATKA RIDGE

In 1950, Kratka Ridge, located approximately fifty miles from Los Angeles on the Angeles Crest Highway near Mount Waterman, was developed by eleven members of the San Gorgonio Ski Club.88 For many years, starting in the 1940s, these skiers spent many weekends skiing and exploring the area. The group members initially built a warming hut and tow for their friends and families. It was north of the existing area, across Angeles Crest Highway, with parking at the top and the rope tow stretching down the canyon. Club members eventually decided to develop their ski area as a commercial enterprise. Since the group included engineers, electricians, a contractor, an attorney and financial experts, it was just a matter of time and money to get the project off the ground. The team possessed most of the skills necessary to get the work done.

The first application for a Special Use Permit for Kratka was submitted to the Forest Service on March 4, 1948.89 That application was submitted by the San Gorgonio Upski Company, whose name was later changed to the Angeles Winter Development Corporation to better reflect the mission of the organization. Five individuals made up the San Gorgonio Upski Company: John H. Belchee, Robert E. Dunne, Everett Lehman, Allan T. Powell and Howard Worthing.

A revised and supplementary application for the development of Kratka Ridge was filed on May 16, 1949. The group wrote:

Further study of the Kratka Ridge area by the original five applicants has resulted in the conclusion that their original plan in respect to the actual development was too limited in scope, and not only was a more comprehensive development required, but that a larger and more completely implemented organization was required to insure the proper and adequate development of the area. Additional members, thus increasing the financial potentiality, have been added to the organization and a name more representative of its purpose has been selected. This application is not, therefore, one by a new and different group but is a revised and augmented application supplementary to the original application of March 4, 1948 filed by the original five applicants herein above mentioned.90

The group felt that ski area development should proceed progressively over a five-year period, with the first and second years as exploratory and experimental. The group explained:

While the area has obviously a high winter use potential unlike Snow Valley and Big Pines, it has not been extensively used. Its detailed characteristics are not fully known. Experience gained under winter conditions alone will answer certain questions. A winter use may indicate changes in the plan or program which will result in a better and more efficient development. Experience at Aspen and Sun Valley revealed that original plans required a great deal of modification and change. Lifts were relocated at Sun Valley and original plans proven inadequate. Aspen required much clearing in areas which were not originally deemed usable. These changes, however, only became apparent after winter use.91

The Forest Service approved the Special Use Permit in 1950. Then the attorney in the group drew up a business plan. This marked the birth of the Angeles Winter Development Corporation and the beginning of Kratka Ridge. Each member agreed to contribute an equal amount of money and a minimum of two hundred hours of labor in the first year of construction. Enthusiasm ran high as the project began, and as it turned out, each man put in an average of seven hundred hours that year, in spite of having full-time jobs.

The Skier provided a telling description of the work and dedication that went into the initial development of the area:

Muscle, vision, money and dynamite have brought the Kratka Ridge project to near completion. The Angeles Winter Development Corporation, a truly cooperative organization, is composed of ten business men who donate equal quantities of time, money and backbreaking labor in an effort to beat the snow.

After a hard day at the office, members of the organization relax evenings at bull-dozing and dynamiting. For relief they install foundations and towers.92

Workers put the finishing touches on the Kratka day lodge, fall 1950. Each of the eleven members of the Angeles Winter Development Corporation put in an average of seven hundred hours of work when development of the area began. Photo by Wolfgang Lert.

Randy Zimmer, one of Kratka’s original developers, working on the handmade stone patio next to the day lodge, fall 1950. Zimmer also managed the area for the first four years. Photo by Wolfgang Lert.

When the area opened for its inaugural season in 1950–51, four rope tows operated, three of which were 1,100 feet long. The fourth was a 400-foot beginner tow. There was also a stylish lodge that included a first aid room, a lounge and a kitchen to provide meals and drinks to hungry skiers. The group named the area Kratka Ridge for John Kratka, an early mountain man who hiked extensively in the area.

The eleven club members who founded the Angeles Winter Development Corporation and worked so hard to see their dream realized were John H. Belchee, a trust officer; Joe Diener, a construction superintendent; Robert E. Dunne, an attorney; Page L. Edwards, a construction engineer and superintendent and president of the group; Frank H. Ferguson, an attorney; Everett Lehman and Allan T. Powell, studio electricians; W. Woodruff Toal, a salesman for a hardwood lumber company; Rex Wakefield, an accountant; Howard Worthing, a mechanical engineer and designer; and Randy Zimmer, a carpenter-contractor. Between them, this group could claim ninety-plus years of skiing experience. Bob Brambach became Kratka’s first ski instructor, followed by Doug Pfeiffer for the next two seasons.

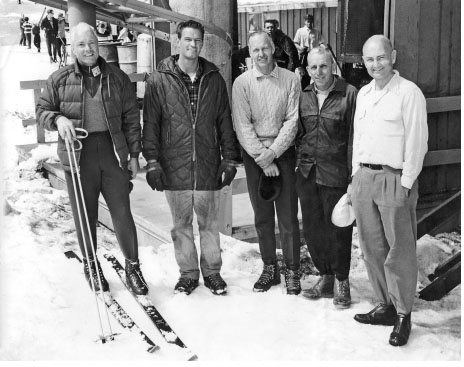

Left to right: W. Woodruff Toal, Edward T. Hensley, Howard V. Worthing, Everett Lehman and Charles K. Jewell. Toal, Worthing, Lehman and Jewell were among the original eleven founding members of Kratka Ridge. Hensley came on board in 1960 and was involved in the management and development of Kratka Ridge for more than thirty years. Courtesy of the Hensley family.

Seeking further upgrades to Kratka, the corporation soon decided to build and install a chairlift. Worthing and Diener visited every area in Southern California that had a chairlift to survey the best features of each, and Randy Zimmer traveled to Switzerland, where he spent two months studying lifts. The developers wanted to combine the best features for the Kratka chair. Worthing’s sheet metal shop fabricated all of the equipment for the lift, including the bull wheel, chairs and towers.

Construction began in 1953. Area owners tackled the arduous job of clearing the land, erecting lift towers and building the upper terminal. Extensive planning went into the chairlift, and the job was described as “an original do-it-yourself project with all members pitching in until the job was completed in December 1954.”93 The two-thousand-foot single chair was equipped with seventy chairs and powered by two Chrysler engines, with one for a backup. The bull wheel, including power units, weighed five tons. The chair had a seven-hundred-foot vertical rise and a capacity of five hundred skiers per hour. In 1957, the chairlift was outfitted with a new, more powerful motor, increasing lift capacity to six hundred skiers per hour.

Skiers ride Kratka’s historic single chair after Mother Nature delivered plenty of fresh snow to the slopes. Photo by Cecil Charles.

In 1960, Ed Hensley became mountain manager at Kratka Ridge. Born in April 1931 in Colton, California, he grew up on the small family farm. He was drawn to the mountains, and in 1949, he and his older brother Bob began to explore and seek part-time work in the Angeles National Forest. In the winter of 1952, he started working weekends and holidays for Lynn Newcomb Jr. Newcomb’s father, Lynn Newcomb Sr., founded Mount Waterman, building the first rope tow there in 1939 and Southern California’s first chairlift in 1942 (chairlift construction began in August 1941). Newcomb Sr. died in 1945, leaving his widow, Livona, and Newcomb Jr. to assume management of the area.

In 1959, Newcomb hired Hensley to manage Newcomb’s Ranch Inn, a small hotel, restaurant and bar that served skiers and mountain visitors, and to assist at the ski area. Hensley, with his wife and three small children, moved into the inn. Shortly thereafter, Newcomb and Hensley parted ways, and during the 1959–60 season, Howard Worthing offered Hensley the mountain manager position at Kratka. Hensley accepted on the condition that he was made an equal stockholder of the Angeles Winter Development Corporation over a short period of time.94

So in the spring of 1960, the Hensley family moved to Kratka and took residence at the upper warming hut. This move seemingly brought good luck to the area. Ray Hensley described the good fortune that took place after their arrival:

What was so striking about our first 1960–61 winter season at Kratka Ridge was that it was one of the best snow ski years ever witnessed in the Angeles. It seemed to snow every week with new powder and not too much to close the roads. The new snow would come on weekdays and the weekends would be clear and sunny at the ski area. The ski area did so well that the owners agreed to help Ed build the Hensley family a three bedroom addition to live adjacent to the single chairlift building and above The Tap Room that summer. The following winter was also good and the Angeles Winter Development Corporation built a new main lodge that still exists today that included owner’s quarters, expanded food service, full service ski rental and repair shop, ski patrol emergency facility and overnight quarters, and ski school overnight quarters.95

This move also signaled the beginnings of the Hensley family’s thirty-three-year reign at the helm of Kratka Ridge. Ray Hensley described the truly hands-on work that shaped and molded the resort: “Ed ran the food services and oversaw maintenance and repair during this last era. I became the hands-on guy as Ed got older. I groomed all night, cleared ski runs, blasted rocks, replaced chairlift engines overnight, built new chairlifts, etc. Tough work and a labor of love. We always referred to ourselves as snow farmers. Or, Kratka being a very expensive hobby.”96

The Hensley family, left to right: Ed, Ray, Mary, Tom and Linda. According to Ray, Ed was the brains and brawn, while Mary was the matriarch to all. Ray, Tom and Linda pitched in where needed and filled their free time with skiing, all three becoming accomplished competitive racers. The Hensley family managed and led the growth of Kratka Ridge for thirty-three years. Courtesy of the Hensley family.

By the mid-1970s, Kratka Ridge had grown to six rope tows, the two-thousand-foot single chair and a day lodge but remained small and was one of the few areas in Southern California that continued to survive with no snow making. Kratka was a lively and vibrant area during this time. Fred Burri, the yodeler for Disneyland’s Matterhorn Mountain ride, entertained skiers on weekends and holidays with his traditional Swiss accordion and yodeling. The area had its own ski club and race team with a membership of more than fifty skiers.

Then, in 1983, Ray Hensley and Jim Morning bought Kratka. They were at the helm for one successful season, but then the deal fell through. The Angeles Winter Development Corporation reclaimed the area and settled with Morning.

By the mid-1980s, the struggles of a Southern California ski resort without snow making became evident. With liability insurance totaling more than $30,000 per year, payable whether the area operated or not, compounded by a season with no snow and thus no income, the days of the ski club–operated or mom-and-pop ski area were things of the past. Ray Hensley commented, “It boils down to the ski areas with snow-making usually have no problems, but the rest of us do. Last year [1986] we were open for 20 days and the year before 18. Three years ago was a pretty good season, but the year before that we were not open for even one day of skiing.”97

In 1988, Ray Hensley began working with the Forest Service on a snow-making plan. But, as with many other Southern California areas, environmental roadblocks slowed or put an end to some projects. Forest Service officials and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would not allow Kratka to use water from a stream where the mountain yellow-legged frog resided. Many scientists felt that the frog should be on the endangered species list. After hearing the bleak news, Hensley said his facility “may soon need to be listed as an endangered species as well. Either make the snowmaking happen or we might as well shut down.”98

The snow-making plan at Kratka was a practical one. The water for snow making would be taken from the local watershed, with about 65 percent being recycled when the snow melted. The plan would require the renovation of a dam on Little Rock Creek and reconstruction of a pipeline that had been used for years to supply water to highway workers who lived at an encampment in the area. Hensley explained that the only time that water would be pumped from the creek would be during rainstorms.

It took eight years from the inception of the snow-making plan for the Forest Service to become concerned about the fate of the frog. Michael J. Rogers, supervisor of the Angeles National Forest at the time, admitted that there had been some delays in dealing with the frog issue but that they were very concerned about the effect the snow-making development would have on the frog habitat.

Rogers explained that the dam renovation would destroy vegetation along the streambed where the approximately fifteen frogs lived. Fish and Wildlife Service officials would not approve the idea of piping water from the frog habitat. They stated that “the proposal will result in significant adverse impact” to the frogs.99 However, Mark Jennings, a Fish and Wildlife Service biologist familiar with amphibians and reptiles in the Angeles National Forest, was open to negotiation. He was in favor of the mountain yellow-legged frog gaining threatened or endangered status but also felt that the individuals involved could arrive at an agreeable resolution to the problem. “If the resort could modify the pipeline to take water further downstream, then I felt that would not bother the frogs,” he said.100 In the same breath, he mentioned that some protection must be given to the frogs. The Forest Service felt the solution to the problem was to develop an alternative water supply through wells.

The Forest Service’s alternative plan required Kratka to spend more money. Hensley said the area had already spent $150,000 on consultants and studies and had no more money to invest in the project.

Even into the 1990s, skiers visiting Kratka Ridge discovered an old-school experience. The area hadn’t changed much over the years. There were no gondolas, no speedy triple or quad chairs, no fancy bars, condos or hotels.

Instead, there is just one rope tow and two simple chairlifts. A few batten-board buildings house a tiny lift-ticket booth, a simple restaurant and caretaker’s quarters. And there’s an outdoor stone fireplace surrounded by picnic tables made from the hand-hewn timber of a tree that fell decades ago on the mountain. At elevations ranging from 6,800 feet to 7,500 feet above sea level, 13 runs are spread over 85 acres of rugged public land, forested by incense cedar, white fir, sugar pine, and Jeffrey pine.101

In 1994, Sam Sarcinelli approached Ray Hensley about buying the ski area for his daughter and son-in-law. He purchased all of the Angeles Winter Development Corporation stock for $325,000, and John and Jacqueline Steely became the new owners of Kratka Ridge. They renamed the area Snowcrest and had ambitious plans to create a more high-profile area. The Steelys hired Ray Hensley to assist in the expansion and development of the area.

The new owners intended to add snow making, ski lifts, toboggan runs, ice skating, snowboard features and cross-country ski trails. Generating excitement for the future possibilities at Kratka, a press release claimed, “Once complete, Kratka Ridge should fulfill the dream of ski enthusiasts across Southern California who wish to swim in the morning, work in downtown Los Angeles during the day and ski in the evening, only one hour away by car. With a population base of many millions of residents, LA is one of the largest sports industry and ski resort areas in the United States.”102

Unfortunately for Southland skiers and the new owners, their plans were not realized. During the winter of 1996–97, they installed snow making on about 25 percent of the terrain at Snowcrest. Unhappy with the performance of the equipment, they removed it after only one year of use.

Sadly, Mother Nature also didn’t cooperate. John Steely recalled, “It was very difficult. We had four of the toughest years in 20 years, and all of our capital went into keeping the business alive.”103

In 1999, a group of Southern California businessmen purchased Mount Waterman and Snowcrest. The group initially went by the name Mount Waterman Acquisition Holdings, but the name was later changed to Angeles Crest Resorts (ACR) to reflect the group’s ownership of both areas. The group was made up of Barry Stubblefield, his brother Gregory Stubblefield, Jim Newcomb and Chuck Ojala, director of mountain operations.

They had bold plans to combine the two resorts, add sixteen or seventeen new chairlifts, develop extensive snow making, construct new buildings and add new rental equipment. Mount Waterman and Kratka, about three miles apart, could be linked by developing the 80 to 100 acres between the two resorts. That would add an additional 300 acres to the 150 at Waterman and the 58 skiable acres at Kratka. According to Barry Stubblefield, chief executive officer of ACR, “Five to 10 years and $75 million later and we’ll have it done, but that’s a wild guess.”104

But they knew, first and foremost, that the key to reviving both areas would be the addition of extensive snow making. During that first season, 1999–2000, ACR created a snow play area that retained the Snowcrest name, while the ski and snowboard section of the mountain returned to the name Kratka. The group eventually dropped the Snowcrest name and changed it back to Kratka, and by February 2000, the first phase of snow making was near completion. The system was laid out to cover the snow play and beginners’ area.

Continued installation of snow making was contingent on many factors: Forest Service approval, availability of water, difficulty of pumping water to the top of the mountain and the creation of a new reservoir. As previous owners had found, the approval process could be slow and difficult.

The initial enthusiasm and optimism of ACR was short-lived. Beginning in early 2001, a chairlift remained inoperative for months. Then, in the summer of 2001, ACR was cited for operating without a permit. Finally, in December, the lift was completely lost in a fire. This began a cycle of disputes with the Forest Service, and over the next four years, ACR often lacked the permits, as well as sufficient snowfall, necessary to operate Kratka and neighboring Mount Waterman.

In January 2005, Stubblefield, the dynamic spirit behind ACR, was killed when he fell and slid out of control into a tree while skiing in icy conditions at Mount Waterman. Friends described Stubblefield as “the motivating forces behind ACR,”105 and without him, the corporation came to a standstill.

Then, in June 2006, with the Forest Service ready to shut down Mount Waterman and Kratka Ridge for good, real estate businessman Rick Metcalf, with his brother Brien and two other investors, jumped at the chance to purchase both areas from ACR. Metcalf had been interested in purchasing the areas when they were sold to ACR in 1999 and now had a second chance at owning both resorts. He admits, “I dove in headfirst without thinking it all through.” A list of things he didn’t expect were “mountain people with quirky personalities; everything that goes into the chairlifts, from the bullwheels to the whisker switches; all the brakes and the emergency things, load testing…the kitchen…”106

Kratka’s historic single chair hangs idle in this summer 2011 photograph. One of only three single chairlifts remaining in the United States, it harkens back to a simpler time of the family-owned ski area when ski lifts and buildings were the result of the labor and sweat of ski area creators.

As of the summer of 2012, Kratka remains closed, eleven years after its last season of operation. Kratka’s historic single chair still rises to the top of the area, one of only three single chairlifts remaining in the United States. The other two single chairs—one at Mad River Glen in Vermont and the other at Mount Eyak in Alaska—still operate. Metcalf has been focused on reviving and upgrading neighboring Mount Waterman. His brother Brien, commenting about Kratka, said that they “don’t have the time or resources for it, so it’s staying in limbo.”107 Their current plan is to operate a tubing and snow play area and, after a number of years, install a new chairlift and open the area for skiing again. Hopefully, the historic single chair can be revived and survive another fifty or more years.