Chapter 5

MOUNT SAN JACINTO AND IDYLLWILD

Russ Leadabrand, longtime columnist for Westways magazine, wrote in his Guidebook to the Sunset Ranges of Southern California, “The San Jacinto Mountains of Riverside County elbow boldly out into the Colorado Desert, yet there are 10,000-foot peaks here and winter snows can be heavy.”108 The most dominant peak, Mount San Jacinto, is a 10,804-foot massif that towers over the town of Idyllwild and is best known for its aerial tramway. The revolving tram car transports mountain visitors via a ten-minute ride from 2,643 feet at the Valley Station near Palm Springs to the Mountain Station at 8,516 feet. This chapter will not provide an in-depth history of the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway, since its primary use is not skier transport nor is it a lost ski area.109 However, this chapter will look at the tows that skiers utilized in and around the community of Idyllwild and on the lower slopes of Mount San Jacinto.

Nevertheless, it is interesting to examine some of the pro-skiing arguments put forward by proponents of construction of the tramway. In January 1939, the Palm Springs Limelight discussed the importance of the winter tourist business and felt that, with the addition of the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway, the town could compete with Sun Valley, Idaho. The newspaper suggested that winter sports might be suitable on Mount San Jacinto, that Round Valley was “a perfect ski country” and that Hidden Lake might be an “ice skaters’ paradise.”110 In the spring of 1940, Modjeska and Masters, a New York engineering company, conducted a seven-week snow survey. It concluded that San Jacinto offered skiing “as good as the best” available at existing ski resorts in Southern California.111

Those in favor of the tramway were promoting the area based on its potential as a prime ski area: “The aim of the ski lift would be to make the long reaches and slopes of the upper regions available to all those who love the sport. If such a lift were installed, proponents of the plan point out, the San Jacinto Mountains would become the mecca for hundreds of winter sports enthusiasts who now go to the San Bernardino Mountains.”112

For several years prior to this time, skiers had already been exploring the potential for skiing in the vicinity of Idyllwild. Most publicity and press on local skiing focused on Mount Baldy, San Gorgonio, Keller Peak and Big Pines. San Jacinto was mentioned occasionally but was not popular with most skiers. In 1934, Walter Mosauer wrote, “Idyllwild, a popular mountain resort on the massif of the San Jacinto Mountains, permits of some good skiing, especially on Tahquitz Peak (8,826 ft.); but generally the country is either too flat and level, or too abruptly dropping, broken, and rocky to be called ideal. Mount San Jacinto itself does not seem to be a good skiing mountain, because of the great horizontal distance covered in its ascent.”113

In spite of the varying opinions regarding the suitability of Mount San Jacinto’s geography for skiing, the first bill presented to the state legislature in 1939 aimed to establish a “Palm Springs Winter Park Authority” for the purpose of constructing the tramway and developing a winter sports resort. The backers of the bill emphasized “the truly unique opportunities for winter sports that the high country of San Jacinto offered.”114

A later bill, proposed in 1945, stated, “There is in the state park system Mt. San Jacinto State Park, which is owned by the state and which is ideally situated for winter sports, including skiing, tobogganing, sledding, and skating, and which affords unlimited opportunities for healthful recreation in a snow area immediately adjacent to the desert recreation of Palm Springs.”115

Interestingly enough, skiers themselves did not support the project. In an article in The Skier, the official publication of the California Ski Association, Andrew Hauk, vice-president of the association, and Lute Holley, chairman of its Area Development Committee, wrote that San Jacinto did not have the suitable terrain necessary for a ski area. Hauk and Holley based their assessment on a survey and report issued on October 7, 1946, by the Southern Area Planning Committee of the California Ski Association and the Winter Sports Committee of the California State Chamber of Commerce. They further commented in The Skier:

After on-the-spot study, the experts who prepared this report, report that the terrain of San Jacinto is extremely rugged, the west slope being heavily timbered and the north, east, and south slopes dropping precipitously from rocky, knife-edge ridges to an upland shelf scarred with ravines and giant boulders, whence it catapults over immense precipices to the desert floor 8,000 feet below. Moreover, the steep and rocky upper 1,500 feet is absolutely unskiable.

The only potentially available ski terrain in the entire San Jacinto area is the rough, partly open slopes between the 8,000- and 9,000-foot levels, approximately 500 feet above and below the level of the upper terminal of the proposed tramway. But these slopes are two miles distant from the terminal, necessitating further transportation facilities not presently planned. There are no up-ski facilities on these slopes nor are any planned. And most importantly, these slopes which face south and southeast require a minimum of 6 feet of snow for safe skiing, a depth which rarely occurs even after heavy snowfalls.116

Many skiers had openly criticized the proposed tramway but none so concisely as Hauk and Holley in their statement:

This project, according to reliable winter sport surveys, by the very nature of its location can never be anything more than a sightseeing attraction. By no sound measure can it ever be a practical skiing development. As those familiar with the area know, Mt. San Jacinto (elevation 10,805 feet) rises out of the desert adjacent to Palm Springs, and while much frequented by campers, tourists, and mountaineers during the summer months, it is by no stretch of the imagination an ideal or even suitable ski area.117

In early 1949, Ralph Accardi, Johnny George, Dick Shideler and Ernie Maxwell completed a high-altitude snow survey and described the difficult terrain they encountered: “There is no easy approach to the backcountry. Sunny southern slopes were frozen and northern slopes too steep to hang to safely. Along the ridge beyond the Peak, a rope was brought into use to prevent anyone from rolling halfway to Idyllwild.”118

The tram opened to much fanfare in September 1963, and in spite of the previous reports detailing the shortcomings of the surrounding terrain for skiing, two months later, the Mount San Jacinto Winter Park Authority retained American Crane and Hoist Corporation of Downey to study and prepare a plan for winter sports facilities at Long Valley near the Mountain Station. American Crane and Hoist hoped to secure the winter sports concession to build and operate portable rope tows, toboggan and sledding areas, ice skating and warming huts. Its proposal was subject to the approval of the Winter Park Authority and the California Department of Natural Resources.

American Crane and Hoist enlisted Economics Research Associates to conduct an economic feasibility study. It hired Willi Schaeffler, a German American ski champion and instructor, to assist in its assessment. Schaeffler was often called upon to determine the geographic suitability for ski area developments and was involved in feasibility studies for Pike’s Peak, Mineral King and other California locations. The study was completed in February 1964, but details were not made public. However, it was known that the survey concluded that additional land for development would be needed and extensive clearing and grading of slopes would be necessary to create ski runs.

The desire for more land led the Winter Park Authority to submit a request to Governor Edmund Brown for use of additional forest land from the summit of Mount San Jacinto to Hidden Lake. The original tramway contract limited land use to two sections in the wild area and prohibited damage to vegetation or alteration of the land. Since the best ski terrain lay outside the existing Winter Park Authority boundary, it asked for four additional sections of land next to the two it already had in the state park. The plan was to clear five ski runs and build two ski jumps.

It is curious that the Winter Park Authority proposed such an extensive plan since its original contract stipulated that no permanent winter sports facilities, such as chairlifts, towers and buildings, could be built. It is also curious that it was planning to build ski jumps. Ski jumping had long before declined in popularity, and the jumps likely would have been little used.

Had the Winter Park Authority’s request been approved, terrain subject to development would have included the top of Mount San Jacinto, its south slopes, Jean Peak, Cornell Peak, Round Valley, Desert View and Hidden Lake.

In April 1964, Norman Wilson, a snow and avalanche expert for the California Division of Parks and Beaches, spent eight days skiing the slopes from Mount San Jacinto to Hidden Lake. He submitted a negative report regarding the possibility of ski development. The Town Crier reported, “Conditions which the skier found to be unfavorable for winter sports development were variation in slopes which causes icy, windy conditions on Mt. San Jacinto, inferior slopes and high cost of manicuring the slopes for suitable ski runs.”119 In addition, Wilson added that ski facilities could be built near the Mountain Station, but the cost would be much higher than the estimates made by American Crane and Hoist.

By December 1964, the Winter Park Authority’s ambitious plan for ski facilities had been denied, and it submitted a new request to construct a “hillalator” and a single ski tow near Mountain Station. The hillalator, or moving sidewalk, would transport tram riders from Mountain Station to Long Valley, a distance of about 370 feet, providing easier access to a nearby snow play area. The ski tow would have been built to the southwest of Long Valley. Winter sports facilities were allowed under the legislative act that created the Winter Park Authority, but only within the confines of specific sections of the state park.

So the 1946 assessment of the mountain as a sightseeing attraction and not a prime ski area proved to be accurate. In the almost fifty years that the tram has been operating, cross-country skiers and adventurous ski mountaineers have accessed the upper slopes of the mountain via the tram, but the area was never developed as a ski area. As more a novelty than anything else, a small rope tow was built near Mountain Station in the 1990s and was removed in about 2000.

In the mid-1940s, all the talk and publicity about a new ski resort in combination with the planning of the tram station at Long Valley motivated the management at Hidden Lodge to lure Tommi Tyndall from Sun Valley, Idaho, to organize and manage its winter sports program. His 1946 arrival signaled the beginning of a dedicated winter sports program for the town of Idyllwild.

Ernie Maxwell, longtime Idyllwild resident, founded Idyllwild’s newspaper, the Town Crier, in October 1946. The second issue, dated November 16, 1946, featured a winter sports story and announced Tyndall’s arrival to town:

Although no Los Angeles papers carry any news about the snow conditions at Idyllwild, Town Crier will take the bull by the horns and state the obvious—that there was, and is, plenty of snow in this neighborhood! At its height, it ran all the way from 9 inches in the Village to a depth of several feet on the peaks.

The bottom of the O’Conner rope tow that was installed near Mountain Station sometime in the 1990s. It was removed around 2000.

A view of the Mountain Station ski school building that served the small rope tow area, circa 1999.

So the time is here for winter sports fans from below to try their ski prowess and romp in the snow and hurl snowballs at one another—and we on the mountain, will gladly join them if we get through with our shoveling before dark!

But with all the added labor that comes with snowtime, it’s a privilege to live in a scene of such quiet beauty. The boughs of the smaller pines curtsey to the ground, laden with the white magic. Pulling our sled homeward one moonlit night, we came upon ski tracks and followed them to our door. There written in bold letters in the snow was the exuberant announcement, “Tommi was here!”

Shortly after his arrival, Tyndall formed the Mount San Jacinto Winter Club, and J.J. Berkeley’s Hidden Lodge became the temporary headquarters for the club. Tyndall, club president, served as the recreational director for the lodge and operated a ski school.

During the 1946–47 season, Tyndall announced that the local ski facilities would be better than ever before. Hidden Lodge blasted rocks and cleared stumps to ready its slopes for anxious skiers. The 1,700-foot ski tow at Hidden Lodge started at an elevation of 6,200 feet and topped out at 7,050 feet. Skiers had their choice of ten runs, five cross-country ski trails and a four-lane toboggan course. The main run was three-quarters of a mile long. After making a test run, Tyndall estimated that expert skiers could negotiate it in forty seconds. This run was dubbed the Gold Ski Course because Mount San Jacinto Winter Club members would use this run to vie for the Gold Star emblem.

In the fall of 1947, J.J. Berkeley left Idyllwild to focus on his business interests in Los Angeles. A group of Idyllwild residents purchased the concessions from Hidden Lodge. Jo Kun (Jo later married Tyndall and would manage Snow Summit after Tyndall’s death) was in charge of the restaurant, Mary Duffield oversaw cabin rentals, Tyndall operated the ski school and Donald Smith ran the toboggan concession.

Tyndall also began dividing his time between Idyllwild and Moonridge Meadows in Big Bear Lake. Jim Neely—a California Ski Instructor Association–certified teacher—and recent Norway import Anders Swanstrom operated the Hidden Lodge Ski School in Tyndall’s absence.

In January 1948, the Town Crier announced, “If you can’t bring the snow to the ski-tow, you take the ski-tow to the snow!”120 Tyndall and Garth Patton began using an army surplus weasel to transport skiers to higher, snow-covered elevations. The weasel left Lookout Café in Pine Cove every hour on the hour. When there was plenty of snow at Hidden Lodge, the weasel operated there.

Tyndall’s stay in Idyllwild lasted little more than a year. The unreliable snow conditions at Idyllwild led him to seek out the higher elevations at Big Bear Lake. He arrived in Big Bear Lake sometime in 1948 and immediately formed his Mill Creek Ski Schools. Jo Tyndall wrote, “He was already deeply engrossed in studying the possibilities of establishing his own business using the white gold in them thar hills when I met him in Idyllwild. He was convinced that a well run ski school could prosper because he felt that skiing generally was about to become big business.”121

When Tyndall left, the Mount San Jacinto Winter Club evidently folded. So in February 1949, plans were underway to organize a ski club. Ray Patton arranged an organizational meeting on February 8 at the Idyllwild Inn. Skiers and non-skiers from Hemet and San Jacinto were invited to attend. Glenn Froehlich was elected president; Webb Ross, vice-president; Barbara Covington, secretary; and Ray Patton, treasurer.

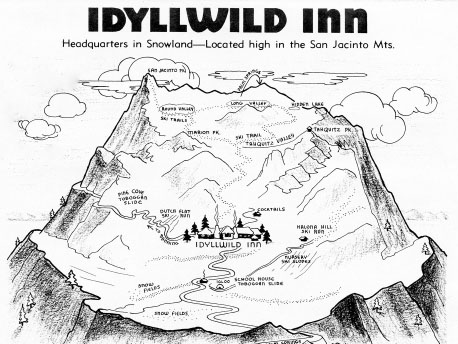

The cover of an Idyllwild Inn brochure highlighting a variety of winter sports available near the inn.

A few other Idyllwild residents tried their hand at building and operating ski tows. In January 1947, Pop Groom and his sons were establishing a winter sports area above Pine Cove (elevation almost seven thousand feet). They planned to have a ski tow, toboggan slide and ski rentals. Then, in January 1948, Bob O’Donnell and Lemmy Poatos purchased four acres on Marian View Drive where they cleared a large ski slope, installed two five-hundred-foot toboggan chutes and made plans to build a rope tow. O’Donnell named his area Halona Hill.

By February 1948, Idyllwild’s two ski centers, Hidden Lodge and Halona Hill, were in full swing whenever snow was plentiful enough. During the first weekend of February 1948, record crowds flocked to both areas. More than 2,500 toboggan rides were logged at the Hidden Lodge toboggan slide, and skiers were swarming the slopes at O’Donnell’s Halona Hill. Garth Patton stayed busy transporting skiers to and from Hidden Lodge.

The popularity of Idyllwild winter sports continued into the 1948–49 season. On the New Year weekend, Halona Hill experienced the greatest number of visitors up to that date. Most of its ski and toboggan equipment was in constant use. The Town Crier reported, “An all-electric ski tow is to be installed at Halona replacing the various contraptions used previously.”122 The electric tow was to be built and installed by Dick Cannon of Hemet.123

A map illustrating winter sports areas, facilities and surrounding trails near the Idyllwild Inn.

A busy day at the Halona Hill rope tow. Founded in 1948, the tow operated until 1964. The ski slope eventually succumbed to cabin subdivision along today’s Lookout Road. Courtesy of the Idyllwild Area Historical Society.

In February 1952, Frank Meadows and Glenn Frankies began operating the tow at Hidden Lodge. The Los Angeles men worked at Hughes Aircraft during the week. Slopes for all levels of skiers were available, but the tow operated on weekends only.

By 1954, Meadows was the sole proprietor of the Hidden Lodge operation and Jim Henley the only operator of Halona Hill. But by 1955, the Hidden Lodge tow was not listed in local snow reports, so Halona Hill was apparently the lone ski tow operating in Idyllwild. At some point in the mid-1950s, Jay Burton became a partner with Jim Henley at Halona Hill. But in March 1958, H.M. Willis, who operated a cabin care business, bought Burton’s share of Halona Hill. The tow again changed hands when Bob Muir took over the operation during the 1959–60 season. He immediately installed a larger motor so up to five persons could use the tow at one time. Unfortunately, Idyllwild’s fickle weather did not cooperate, and the 1960–61 season was snowless. The tow did not operate during the 1961–62 season even though Idyllwild had its best snowpack in five years. Even when the tow wasn’t running, Halona Hill was used for all manner of snow play. It is not known when the tow was retired permanently, but on January 25, 1964, even though it hadn’t been scheduled to open, the tow went into operation, much to the delight of the snow sports enthusiasts who had flocked to Idyllwild for a weekend of winter fun. This may have been the last hurrah for Halona Hill and its rope tow that served Idyllwild skiers for more than twelve years.

A recurring scene at many Southern California ski areas that received marginal snowfall. These Idyllwild skiers relax in the sun amidst the patchy snow at the base of Halona Hill. Courtesy of the Idyllwild Area Historical Society.

Today, there are no ski tows operating on Mount San Jacinto or in Idyllwild. Cross-country skiers still use the tram to access winter snow, but Mount San Jacinto or Idyllwild never became the winter sports destination that many argued it could be.