I can’t imagine having a career conversation with a Japanese person in which the topic of wabi sabi comes up. The word ‘career’ brings to mind striving, competition, pressure, a particular goal. Wabi sabi evokes pretty much the opposite of all those things. But having spent almost a decade helping people to shift to a career that lights them up, or to find new ways to fall back in love with the one they already have, I can see that there is actually much we can learn by viewing our careers through the lens of wabi sabi .

That core teaching of wabi sabi – that everything is impermanent, imperfect and incomplete – feels to me like a giant permission slip to explore and experiment within your career. Although we tend to think about a career as a linear thing, wabi sabi reminds us that life is cyclical, and we can have more than one ‘career’ in our lifetime. This chapter is all about how to enjoy the career journey , and that starts with understanding where you are right now, so you can choose how to move forward.

The virtuous cycle of perfect imperfection

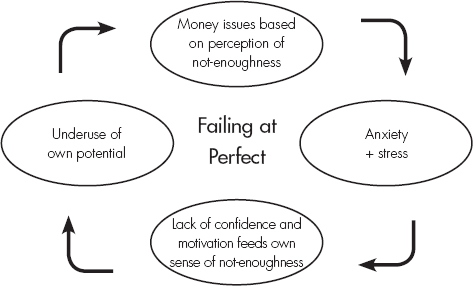

The conflicting desires to fit in yet stand out, keep up and surge ahead, all in pursuit of an elusive perfection over there is a huge distraction from the life you already have over here.

In my work, I have come to realise just how influential the lure of perfection can be, and not in a good way. It seeps into every area of people’s lives, not least in their careers, crushing confidence and self-esteem, and raising anxiety and stress levels. It also has a practical impact on how people allocate their precious resources – in particular, time and money.

The five main career scenarios that I come across in my work are:

1. ‘I love my job but find it too stressful. I’m not sure if I want a career change, or a job change or just to find a better way of working.’

2. ‘I hate my job, but feel stuck (by a lack of self-confidence or ideas about what else I could do) or trapped (by circumstances, such as finances or commitments).’

3. ‘My job’s OK and it pays the bills but … [or ‘I am good at my job but …] I dream of something else [very often something more creative], although the idea of actually doing it terrifies me.’

4. ‘My main job recently has been parenting. I am planning to go back to work, but need more flexibility in my working hours or arrangements, and I’m not sure my old job is even right for me any more.’ Alternatively, ‘I am proud of the time I have spent raising my children, but I want something for myself now they are older.’

5. ‘I have been made redundant and I cannot figure out whether it is a nightmare or a blessing in disguise.’

In nearly all cases, what my clients think is the issue, is rarely the actual issue. Lots of people cite ‘money’ and ‘time’ as their main challenges, but that is usually a matter of some smart prioritising (and Chapter 8 includes some tips to help you with that). It’s also often the case that they are in the dark about just how many opportunities there are nowadays for flexible and remote working, or running our own businesses.

However, beneath all the resistance to change and the feelings of ‘stuckness’, lies the real block: fear of not being good enough; fear of not knowing enough; fear of failure; fear of making a move without knowing how it will work out; fear of losing control (not that we are in control in the first place); fear of not being perfect. And although each person’s situation is different, I have seen a pattern emerging – a vicious cycle of ‘failing at perfection’, which looks something like this:

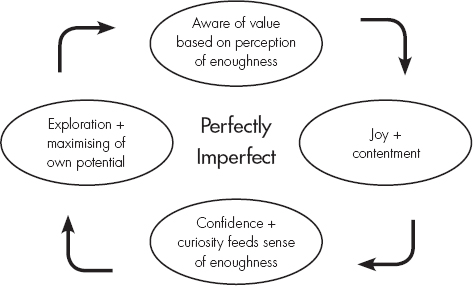

We can use all the wabi-sabi -inspired wisdom and tools I have shared in this book to break this cycle, as we accept the idea of impermanence, imperfection and incompleteness as the natural state of all things. But there is also a huge amount to be gained by simply relaxing, being gentler on ourselves and making the choice to enjoy the journey.

Collectively, this can help us shift to a ‘perfectly imperfect’ virtuous cycle like this:

Use your wabi-sabi -inspired tools

Whenever I am on a panel or run open forums for people in business, I am almost always asked a question related to competition, comparison or enough-ness. It’s very hard to run a business with your eyes open and your ear to the ground and not find yourself comparing your ‘success’ to the ‘success’ of others.

This is also true in the world of salaried work. It’s difficult to stay alert to what is going on in your workplace and your industry without running into situations that encourage comparison and competition. For as long as this helps you aspire to something you genuinely want, it can be helpful. But as soon as it detracts you from your own path, it can be damaging.

The thing to remember is this: someone else’s success does not hinder your chances of achieving what you want. Their success may even open up new opportunities for you and others. They will walk their path; you are supposed to walk yours. You have everything you need to go wherever you want to go.

It’s just as important to use your tools for nurturing relationships, reframing failure and accepting your perfectly imperfect self at work as it is to use them in your life outside work. If you show up with integrity and allow your inner beauty to shine, any workplace and any client will be lucky to have you. If they don’t show you their appreciation, check in with your heart and see if it’s time to move on.

The imperfect path your heart guides you along is the perfect path for you.

Look beneath the surface of your current career

Not long ago, I was in an external meeting where the icebreaker was: ‘If we take away your work, what else do we find?’ One of the women there froze. You could see the dawning of a realisation moving like a wave through her body. ‘Nothing. I am my work. And I didn’t realise that until this moment. Oh wow, I wasn’t expecting that. Something needs to change.’

That woman is one of the most brilliant, inspiring, funny and warm people I know. And yet she couldn’t come up with anything to say about her life that wasn’t connected with work. I happen to know that she has a half-finished manuscript tucked away in her desk, a deep love of travel and a circle of lovely friends. But she had pushed all those things away in the pursuit of an elusive goal of career perfection, with the result that her work had moved in and swallowed up all the space. It had become all about what was on the surface – the achievements, the appraisals, the promotions, the salary and status, the mantle of busyness. She had, as do so many of us, forgotten that what lies beneath matters too.

So let’s take a moment to remind ourselves of those four emotional underlayers of Japanese beauty, and see what happens if we layer them over our career paths:

Mono no aware

An awareness of the fleeting beauty of life.

1. What is good in your career right now?

2. Consider the life and career stage you are in and complete this sentence: ‘Now is the moment to …’

3. What do you need to do first, in order to make the most of this moment?

Yūgen

The depth of the world as seen with our imagination. The beauty of mystery, and of realising we are a small part of something so much greater than ourselves.

1. How much are you trying to control the direction of your career path? What might happen if you let go a little, and opened up to mystery?

2. What deeper purpose are you serving or could you serve with your career?

3. If you have untended dreams that have been shelved for too long, what kind of changes could you make to your working arrangements to give them some attention?

Wabi

The feeling generated by recognising the beauty found in simplicity. The sense of quiet contentment found away from the trappings of a materialistic world.

1. How could you simplify your work life? How could you proactively reduce your workload and streamline communications to focus only on what really matters?

2. How could you minimise the drama, avoid the politics and gossip, and invite more calm into your working day?

3. If you are overworked due to your perfectionist tendencies, what space might open up for you if you trusted someone else with some of your work?

4. If you feel like you are just working to pay the bills, could you take a fresh look at your finances, and figure out a way to live more simply, so the burden on your work is not so heavy?

5. Does your work come easily to you? In what ways are you using your natural talents? How could you do this more?

Sabi

A deep and tranquil beauty that emerges with the passage of time.

1. How has your career ripened over the years? What have you learned?

2. Are you trying to force your career too fast? What difference would it make if you relaxed into the rhythm of it, allowing the richness to build over time?

3. If you feel it’s time for a change, what skills have you picked up that could serve you elsewhere? What have you learned in the great school of life that could serve the next stage of your career?

Just as these emotional elements of beauty are of great importance in Japanese aesthetics, they can be important guides on your career path. They require pause, attention, tuning in and being open to wonder.

Life in contemporary Japan

For a period of over two hundred years from the early seventeenth century to the mid-nineteenth century, Japan was virtually closed off from the world through a national isolationist policy known as sakoku . This ended when Commodore Matthew Perry and his famous ‘Black Ships’ arrived in Tōkyō Bay from America in 1853 and forced Japan to open to trade once again. Within five years Japan had signed treaties with other countries including the United Kingdom and Russia.

The influx of ideas and technology that followed had an irreversible effect on the lifestyle of the Japanese. The country’s subsequent rise, post-World War Two, from economic insignificance to world player, brought with it Westernisation – Western clothes, Western style and, to some extent, Western thinking. Since then, Japan has become a hi-tech, high-earnings world. The people have become affluent and a high standard of living prevails. With this new-found wealth have come the rapid growth of cities, a proliferation of skyscrapers and the famous bullet train.

Even if you have never been to Japan, you probably have an image of what working life looks like. Perhaps it involves suited ‘salarymen’ or the unfortunately named ‘OL’ (office ladies), packed into commuter trains by white-gloved station officials; or exhausted workers nodding off on their journey home. Maybe the Japan in your mind’s eye is the iconic image of pedestrians surging forward at Shibuya Crossing, under the glow of neon signs and giant screens – thousands of people with somewhere to be.

Tōkyō has an incredible energy, and millions of people do live this commuter life there, and in cities across Japan. I was one of them many moons ago, and there were aspects of it that I loved. But more than ever, as in so many places around the world, options are opening up for people who don’t want to live and work in such a hurry any more.

The slow revolution

Nestled deep in the mountains of Shimane Prefecture lies the charming town of Ōmori-chō. At its peak, a couple of centuries ago, the surrounding area of Iwami-Ginzan bustled with the energy of 200,000 people serving one of the world’s largest silver mines. But when the mine closed in 1923, the town, like many former mining communities, slowly began to die. At one point, Ōmori-chō’s population dwindled and may have disappeared completely were it not for a huge local effort, including that of one pioneering couple, the Matsubas, who moved here in the early 1980s and helped breathe new life into the place. Now Iwami-Ginzan is recognised as a beacon of sustainable development by UNESCO. 1

Designer Tomi Matsuba and her husband, Daikichi, moved here nearly four decades ago, with their young daughter. Ōmori-chō was Daikichi’s home town, and they thought the gentle pace of life would better suit their young family than Nagoya, where they lived. With few opportunities for work, Tomi began making patchworks from old fabrics, which her husband sold into retail stores. This was the humble beginning of a business that has gone on to become a leader in Japan’s slow clothing scene, 2 with stores nationwide under the brand name ‘Gungendō’ 3 (which takes its name from a Chinese word meaning ‘a place where everyone has their say’). Their company now employs around fifty local residents, and many more in their stores nationwide.

Tomi told me:

We do not see ourselves as a fashion brand. Increasing numbers of people share our values, and that is why they are drawn to our products. It is our mission to maintain the quality and heritage of all we offer, and to support people to live in a gentle and authentic way.

Besides using locally sourced natural materials and labour to produce their stylish clothing and housewares, Tomi and her husband have undertaken the renovation of several historic buildings, to preserve the history of the area. Overnight visitors are treated to some of Japan’s finest traditional accommodation, 4 and a number of the buildings are used by the community for arts performances and exhibitions.

These days, if you take a stroll down Ōmori-chō’s main street, you might see a group of young mums chatting outside the bakery, a few people heading to work on their bicycles or a couple of older friends on their way to pick mountain vegetables. You’ll walk past rows of carefully maintained wooden houses and hear people calling gentle greetings to each other, as they go about their day. This town is the embodiment of slow living, and there is a tangible sense of place, and of pride in the community from those who call it home.

The life and career Tomi has built here has been a labour of love, and her work has evolved many times along the way. She is a pillar of the community, and can be proud of her role in bringing it back to life. There has been a particular influx of newcomers since the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, which prompted many people to reconsider the importance of material success, and prioritise what really matters.

Not only are Tomi and her husband blazing a trail for sustainable business, they are also active as shining examples of how a career can be multi-faceted and continually evolving. When they began, they had no idea where this adventure would take them. Now a grandmother, Tomi is still full of ideas and energy. Her life’s work will never be done, and she is grateful for that.

Gungendō’s mantra is ‘Life with roots’. Tomi says, ‘Our ideal lifestyle is like that of a tree – putting down roots which spread through the land, standing firm and growing slowly. Enjoying our daily lives as we take root in the land, pursuing long-term goals and having a positive influence on those around us.’

Personally, I am particularly inspired by the fact that Tomi began Gungendō when she was forty-three, not much older than me as I write this. It’s never too late to create something special. Tomi reminds us how a career can unfold to reveal a scattering of shining treasures, only evident when you surrender to the journey and follow your heart, adopting a career philosophy, not a single career goal.

Walk your own path

One of my favourite kanji

in the Japanese language is the character ![]() which, when it is read ‘michi

’, means ‘path’ or ‘road’. But it is often used in combination with other characters to mean ‘the way’, in which case it is read dō

. You may have heard of it: chadō

and sadō

(different readings for

which, when it is read ‘michi

’, means ‘path’ or ‘road’. But it is often used in combination with other characters to mean ‘the way’, in which case it is read dō

. You may have heard of it: chadō

and sadō

(different readings for ![]() ) refer to ‘the way of tea’,

bushidō

(

) refer to ‘the way of tea’,

bushidō

(![]() ) is ‘the way of the warrior’ and Japanese calligraphy is known as shodō

(

) is ‘the way of the warrior’ and Japanese calligraphy is known as shodō

(![]() ), ‘the way of writing’. Among popular martial arts, we find jūdō

(

), ‘the way of writing’. Among popular martial arts, we find jūdō

(![]() ), ‘the way of gentleness’, and karatedō

(

), ‘the way of gentleness’, and karatedō

(![]() ), often known outside Japan simply as karate

, the ‘way of the empty hand’.

), often known outside Japan simply as karate

, the ‘way of the empty hand’.

In much the same way, our careers are paths. When we look back on the road we have walked thus far, we see that it is not just winding – it often goes back on itself; there are gentle curves and hairpin bends. Effort matters, and commitment is rewarded. The time it took to get to where we are is not the point. The time it will take us to get to where we will go next is not the point. In fact, the results themselves are not the point: the way you get to your results matters more than the results that you get.

Lessons from the dōjō

These days, you are more likely to find mixed-media artist Sara Kabariti in her painting studio than in the dōjō , but almost three decades on from time spent training in martial arts in Japan, she says that experience still informs her life on so many levels. ‘In a nutshell, I learned how to learn. I learned the importance of discipline, hard work and persistence, but also approaching everything I do with great passion and joy. I spent many hundreds of hours practising over and over, working on my form and strength.’

NTC’s Dictionary of Japan’s Business Code Words

, under the entry for shūgyō

(![]() – translated as ‘training for intuitive wisdom’) confirms this: ‘In the Japanese value system, the way things are done outweighs what is done … The Japanese believe that the harder something is to learn and the more effort that is required to learn it, the more valuable the knowledge or the skill.’

5

– translated as ‘training for intuitive wisdom’) confirms this: ‘In the Japanese value system, the way things are done outweighs what is done … The Japanese believe that the harder something is to learn and the more effort that is required to learn it, the more valuable the knowledge or the skill.’

5

In Japan, form is everything. This is true both in the hand-crafting of items (which explains why artisans will take decades before they truly recognise their own skill) and in their attitude to life (which explains much of the formality and ritual in Japanese life). Potter Makiko Hastings described how she strives to improve the form of her craft, without ever expecting to attain absolute perfection. She knows that imperfection is the true nature of things, so she works at edging closer to the best she can do and be, without a false expectation of where she will end up.

Excellence over perfection

When the notion of excellence is used as an aspirational motivator, it can be hugely valuable. This is in stark contrast to working towards an elusive goal of perfection with the expectation we will ‘arrive’, burning ourselves out as we relentlessly push on forward, and ending up disappointed because the destination was never reachable in the first place. The difference in understanding is subtle, but the impact is immense.

This attention to form paid off for Sara Kabariti. Recalling the time she competed at the European Jōdō Championships, 6 she told me how the prospect of one particularly long kata (move) was making her really nervous. Her teacher came over and said, ‘Sara, after all your training, your body knows what to do, but your mind won’t allow it to do it.’ At that moment, she understood and let go. She knew that we have to set intentions, show up to practice, do our best. And then trust. She and her partner went on to win the gold.

Sara says:

It’s when we let go and trust that the magic really begins to happen. The Japanese are masters at finding the line of least resistance, even if it doesn’t seem like the logical route. Martial arts teach us to go with the flow of energy and motion, not against it. I also learned that the minute you think you either know it all or you think you cannot do it, you have lost it. I was shown early on to be open and fully in the present moment. Letting go is both a major life lesson and a daily practice. We can set intentions, and show up for practice, but there comes a point where we have to trust and allow things to fall into place in good time. My mantra these days is ‘surrender’.

Set your own pace

To make progress in the direction of your dreams, within the context of your perfectly imperfect life, you will need preparation, dedication and trust in yourself and in the process. You have to let go of the need to have all the answers or a ‘perfect’ picture of the future before playing your part in creating it. A wabi-sabi- inspired world view gives us permission to feel our way through life, paying less attention to what we think others think (or what we think we should do based on what others think) and more attention to what really matters to us. Keep asking questions, and keep moving, sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly, depending on the ebb and flow of life.

In reading Nihonjin no kokoro, tsutaemasu

, a short book about the world of tea by former iemoto

(head) of the Urasenke school of tea, Sen Genshitsu, I came across the word johakyū

(![]() ). This refers to three different speeds of action – slow, a little faster and fast.

7

Sen Genshitsu explained how there is a tempo to the tea ceremony, and practitioners must vary the speed as required. He went on to say how they must vary their effort level too – sometimes being gentle, sometimes adding a little strength, sometimes really going for it. As he concluded, this can also be great advice for life.

). This refers to three different speeds of action – slow, a little faster and fast.

7

Sen Genshitsu explained how there is a tempo to the tea ceremony, and practitioners must vary the speed as required. He went on to say how they must vary their effort level too – sometimes being gentle, sometimes adding a little strength, sometimes really going for it. As he concluded, this can also be great advice for life.

I have talked a fair bit about slowing down to allow yourself to notice more, sense more, see more and experience more. This comes from a starting point of rushing, which seems to be the default pace for so many of us these days. But slowing down doesn’t mean calling time on a desire to do meaningful work in the world, or having ambition or getting involved in exciting things. Slowing down is important as a counterpoint to running fast, and sometimes it’s good to vary the pace.

And just as Sen Genshitsu said, varying our effort levels is vital for our wellbeing too. We cannot give any project, meeting, opportunity or conversation our full attention when we are trying to juggle many things at once. We have to prioritise well, get organised and focus on one thing at a time.

We have to put our effort where it is going to have the greatest impact, and take us in a direction we actually want to travel in. And for every time we give something our everything, we have to put other things to one side. After a major effort, we have to build in recovery time, and give ourselves permission to take it easy for a while. Using these three gears of speed and three gears of effort can make all the difference to whether or not we enjoy our career journeys, and stay well along the way.

Being open to change

The world of work is changing at the fastest pace since the Industrial Revolution. Many traditional job roles are disappearing, and new opportunities are opening up. None of us can know what a career will look like fifty years from now. We can try to hold on to how things are, or we can embrace the evolution, making the most of it to carve out a career that supports the kind of life we want to live.

This statement has never been truer, when rapidly evolving technology has given many of us the option to work from anywhere, to any rhythm we choose. More than ever, we have to recognise that even if we don’t change, the working world will. The impact on our careers will be determined by whether we embrace that, or try to hold on to the status quo, even as the status quo is shifting.

Our skillsets are not usually industry-specific, and can serve us in many ways. When we relax into the knowledge that our careers are dynamic, not static, we open ourselves up to unknown possibilities. Recognising and planning for the impermanence of the jobs we once thought were secure makes us better prepared if changes are imposed upon us, and reminds us that if we are having a hard time, we don’t have to do it for ever. Would we even want to? We are likely to want very different things at twenty, forty, sixty and eighty years of age.

There is no single perfect career path. There is only the one that we are constructing as we go.

All of this goes against everything many of us have been taught about how to be successful – that we should follow one path and stick to it, that money and status are the goal, that if you don’t reach some particular image of perfection you have failed. Having spent most of the past decade helping people shift between careers, start their own businesses or reprioritise to do more of what they love, I know that attitudes are slowly shifting, but we have a long way to go. On the whole, from what I have seen in my work, we still care far too much about what other people might think, and don’t pay enough attention to what makes sense for us.

We increasingly need to be able to see, read, empathise, question, adapt and course-adjust to accommodate this transitioning world of work. Experts tell us that some of us, and likely many of our children, will live to one hundred and beyond. 8 What difference would it make if you knew that this was going to be true for you?

Questions for looking at the long view

• What difference would it make if you knew you would be likely to be working well into your seventies, or even your eighties?

• Do you want to be doing what you are doing now, until then, presuming that kind of work still exists?

• If not, what kind of work might suit you later in life?

• What difference would it make if you knew that your current career would have its moment and then fade, to make way for another?

• Would you have a different approach to your current role?

• What skills or training might you explore?

• Would you give your creative ideas or side business more attention?

• What else would you nurture?

Now, ask yourself those questions again but this time, instead of looking for the logical answers, tell me this: what does your heart say?

Remember, your heart’s response to beauty is the essence of wabi sabi . So what kind of beauty could you create with your career?

What does your heart say?

Ask the kind of questions that prompt inspired answers

When we ask children, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ we are usually trying to sow the seeds of dreams. But then we sometimes respond in a way that crushes those dreams and can cause long-term damage. ‘An artist? Oh no, dear, you don’t want to be an artist. You can’t make money doing that.’ Or children end up attaching their dreams to a specific job they think will make us proud, in many cases the same job they see us doing. It’s what they know, or what they think we’d like them to do, or what we keep telling them we think they should do.

But then what if they don’t make it into that profession? Or if they do make it, and don’t like it, but don’t want to leave because they feel like they’d be letting us down? Or if they get caught up in a cycle of hustling and jostling for position, status, clients, salary and recognition and, before they know it, they are in midlife, burned out and wondering what happened to the past twenty years? I’m pretty sure none of us wants that for our children or, indeed, for ourselves.

All of these are examples of things I have seen happen time and again to real people in my community. People come to us for support in discovering how to do what they love because they can no longer stand to do what they are doing, but don’t know how to change or figure out what else they could do. The good news is they have no idea just how vast the possibilities are.

A recent international report on the future of work, based on surveys of over 10,000 people across Asia, the UK and USA stated: ‘We are living through a fundamental transformation in the way we work. Automation and “thinking machines” are replacing human tasks and jobs, and changing the skills that organisations are looking for in their people.’ 9

As part of the same report, Blair Sheppard, Global Leader of Strategy and Leadership Development at PwC said: ‘So what should we tell our children? That to stay ahead, you need to focus on your ability to continually adapt, engage with others in that process, and most importantly retain your core sense of identity and values.’ 10

Questions we can ask to invite a different kind of career journey

• What inspires you?

• What matters to you?

• What would you like to create?

• What would you like to change?

• What would you like to experience?

• How could you help people?

• What kind of place would you like to work in?

• What kind of people would you like to work with?

• How would you like to spend your days?

• How do you want to feel about your work?

• What assumptions are you making about your opportunities that may not be true?

It bears repeating: there is no single way to live your life; there is no single career path; there is no perfect way to build your career. There is only evolving it, and it’s up to you if you choose to do that in a way that brings you delight.

The waking dream

There’s something about Japan that has always made me feel that anything is possible. Even back when I couldn’t read any signs, hardly knew anyone and could barely hold a conversation, I always felt something in the air that gave me an extra boost … of what, I’m not quite sure. But that ‘something’ made me open and curious, and led me to all sorts of experiences I could never have imagined, from life-altering encounters with random strangers, to hosting my own TV show. In some ways, it felt like a waking dream. Even now, when I return, it often still does.

I want to gift you some of that, wrapped up like a treasure in a furoshiki cloth, 11 to offer you inspiration and nourishment on your career path. Every time your dreams seem to be disappearing to the periphery of your life, untie the furoshiki and inhale a little of the magic. Take a moment to bring your dream into your field of vision, then bring yourself back to the present and feel your way to the next step on your path. Ask yourself, what is the one thing you could do right now, to take you closer to that dream? What does your heart say?

We cannot know the timeline. We cannot predict the path. But we can be intentional in our steps, and pause once in a while to experience the beauty all around.

![]() (nichinichi kore kōnichi

)

(nichinichi kore kōnichi

)

Every day is a good day.

Zen proverb 12

WABI-SABI

-INSPIRED WISDOM

WABI-SABI

-INSPIRED WISDOM

FOR ENJOYING YOUR CAREER JOURNEY

• There is no one perfect career path.

• Your path may contain several different careers, each supporting your priorities, as you move through the cycle of your life.

• The way you get to your results matters more than the results that you get.

First, in a notebook, answer these questions:

• What jobs or roles have you had, either paid or unpaid, that taught you something? (Make a list.) What did each teach you?

• What have you studied at any level that you found interesting? This can be absolutely anything where you have spent time to learn about something in depth, either formally or informally.

• What other major experiences have you had?

• What particular moments of fleeting beauty stand out in your memory?

Next, on a double page, draw a horizontal timeline, with vertical lines to mark each decade (or every five years if you are under thirty). Looking at your answers to the above questions, map out the most important experiences so far in your life. Mark any points when you had an ‘Aha’ moment.

Now draw lines between the things that are connected in some way. What had to happen for something else to happen? What themes can you see?

Now, with all the information in front of you, answer these questions:

• What have been the most important career decisions affecting your happiness along the way?

• What or who are you particularly grateful for on your career path to date?

• What do you need right now?

• What is the one thing you could do to step into the next phase of your career with intention and trust, whether that is deepening what you already do or moving in a new direction?