Chapter Four

In the days and weeks that followed, he asked quite a number of small creatures whether they were mice.

He asked beetles and grubs and worms and caterpillars and little lizards and small frogs, and some replied jokily and some replied angrily and some didn’t answer. Till at last Poppet rather forgot about his mother’s dire warning and gave himself up to enjoying the carefree life of a baby elephant. He used his trunk for reaching up and pulling down leaves and twigs, and for sucking up water when the herd went to the river to drink, and then blowing water all over himself. When he was nice and wet, he would go to a dusty place and use his trunk to give himself a dust-bath, so that he finished up beautifully muddy. Then he’d go back into the river and have a lovely bathe, going right under the water, with just the tip of his trunk sticking up above the surface, like a snorkel.

A trunk, Poppet decided, was a brilliant thing to have.

As for mice, he never thought about them any more.

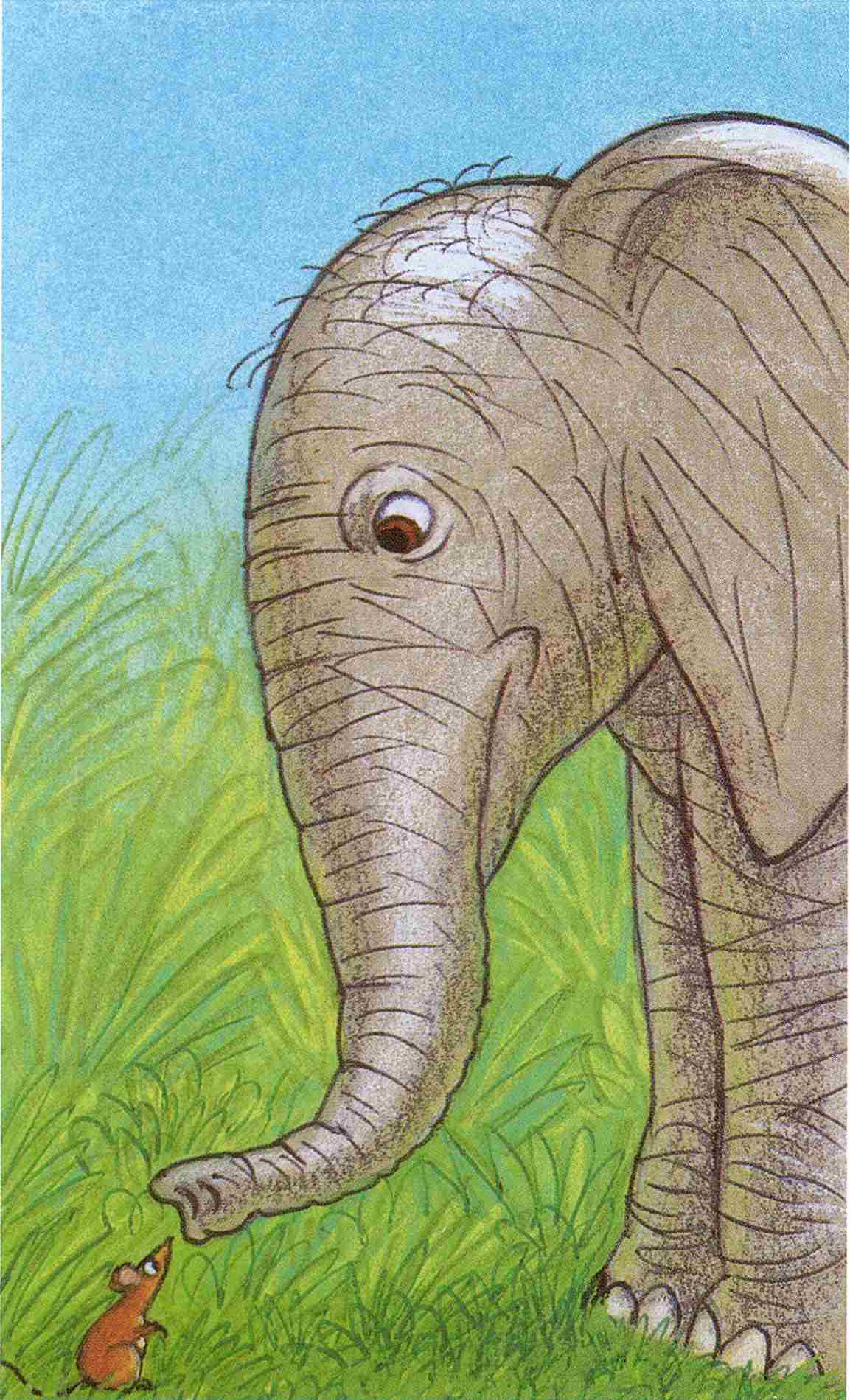

Then one hot afternoon, when he was about a month old, and his mother and all the aunties were standing resting in the shade, Poppet wandered off a little way, exploring.

He was using his trunk to search about in the grass as he went along, when suddenly he saw in front of him an animal that he had not previously met. It was furry and brown, with large tulip-shaped ears, beady black eyes and a longish hairless tail, and Poppet stretched out his trunk towards it and sniffed at it.

Even when the tip of his trunk was right before the creature’s face, it didn’t occur to him that this animal was small, and – without much hope because he’d been wrong so many times – he said, “Are you a mouse?”

“As a matter of fact,” said the animal, “I am. And you know what mice do to elephants, don’t you?”