Long after the sun has set behind the Palatine Hill, after the sands of the Colosseum have been swallowed by shadows, after the tint of the Tiber has morphed from acqua minerale to Spritz to dark vermouth, you come upon a quiet piazza down a meandering cobblestone street where a beaming restaurant owner—“Tonight is your lucky night,” he says, Italian accent clinging to his English like a coddled egg to a carbonara—ushers you to a checkered-tablecloth table and asks if he might be allowed to read you the daily specialties while you settle into the evening, and by the time he’s finished explaining the brilliance of the braised oxtail and the two types of seasonal ravioli, made by hand every morning, a basket of bread and a carafe of wine have nestled in next to your elbows and you’re just about ready to write home and tell your loved ones that all bets are off.

At the next table over, two Barolo-bellied men, teeth stained purple with Chianti, argue about Serie A soccer, the proper cutoff hour for a cappuccino, whose mother makes a better ragù. Every so often, a couple wanders out of the shadows and into the light of the restaurant, only to be turned gently away by the owner (“Try again tomorrow!”), making this moment just a bit more delicious. On the way to the bathroom, you catch a glimpse of a grandma in the kitchen, forearms coated in a fine layer of semolina, moving between the pasta bench and her seat next to the stove. The food dispatched from her kitchen perch will be the first and last thing you tell everyone about back home.

The wine keeps coming long after you stop ordering it. The owner makes the rounds, shaking hands and proffering glasses of his sticky homemade limoncello as the low purr of conversation rises with the moon. And as you slide your spoon through the last ripple of cocoa-laced mascarpone and savor the final drops of a bittersweet espresso and the night feels suspended in some blissful state of animation, you lean back in your chair and wonder: Wow, so it really is like this?

* * *

Only it’s not really like this. Those tables filled with gesticulating Italians are actually filled with slow-blinking Americans and Brits and Japanese. That impossibly cheap and delicious house wine is an unholy mix of wounded soldiers left behind from nights past. Those flickering lights are in fact electric candles bought at the new IKEA. And that grandma with rivers of time running through her fingers, lost in the kneading of fresh tonnarelli, is actually an underpaid cook from Cairo, bringing his own traditions to the table.

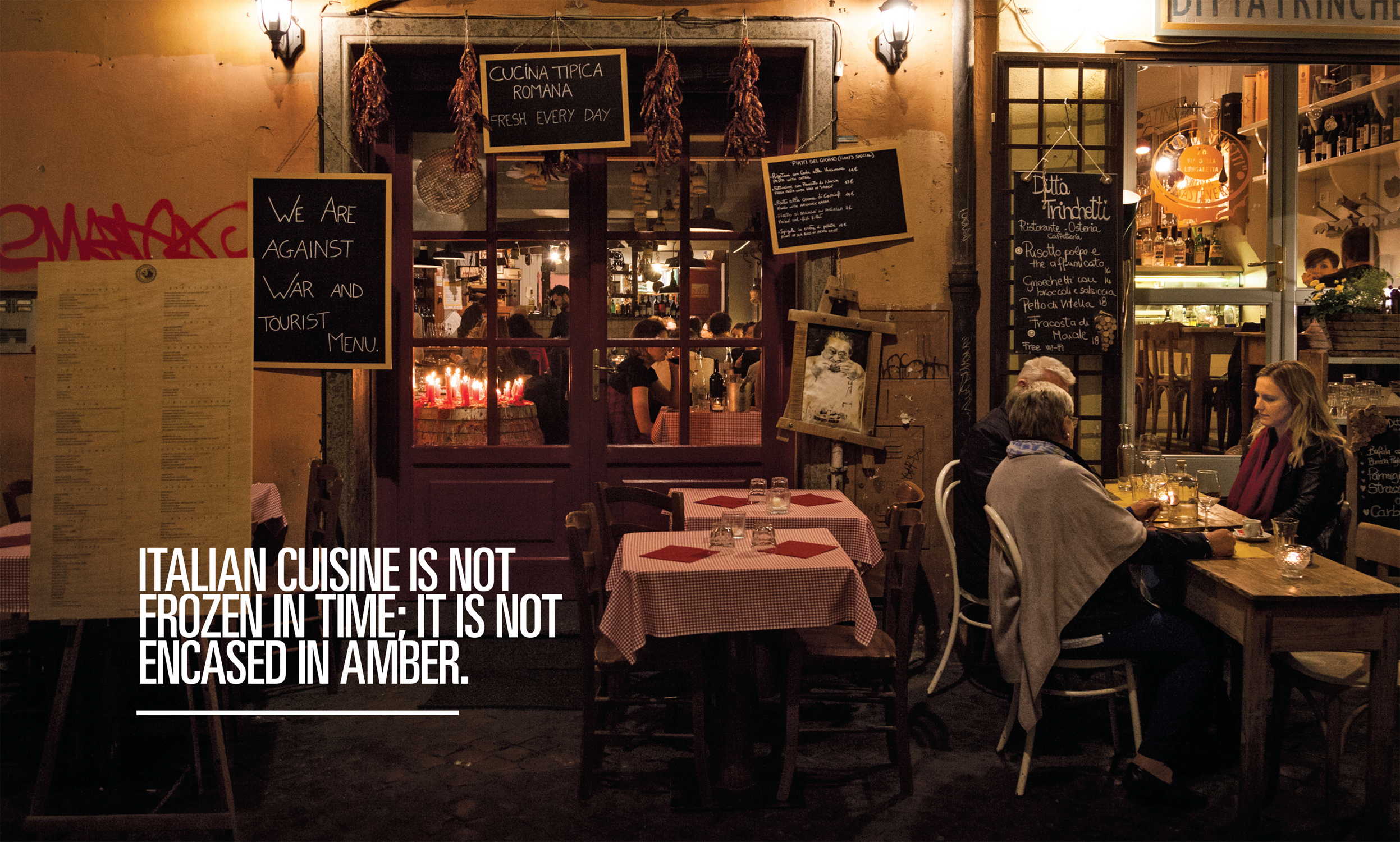

Italian cuisine is the most famous and beloved cuisine in the world for a reason. Accessible, comforting, seemingly simple but endlessly delicious, it never disappoints, just as it seems to never change. It would be easy to give you, dear reader, a book filled with the al dente images of the Italy of your imagination. To pretend as if everything in this country is encased in amber. But Italian cuisine is not frozen in time. It’s exposed to the same winds that blow food traditions in new directions every day. And now, more than at any time in recent or distant memory, those forces are stirring up change across the country that will forever alter the way Italy eats.

That change starts here, in Rome, the capital of Italy, the cradle of Western civilization, a city that has been reinventing itself for three millennia—since, as legend has it, Romulus murdered his brother Remus and built the foundations of Rome atop the Palatine Hill. Here you’ll find a legion of chefs and artisans working to redefine the pillars of Italian cuisine: pasta, pizza, espresso, gelato, the food that makes us non-Italians dream so ravenously of this country, that makes us wish we were Italians, and that stirs in the people of Italy no small amount of pride and pleasure.

If you know anything about Italy, you know change doesn’t come easily here. More than any other cuisine on Earth, Italian is one imbued with a sense of timelessness and immutability, the recipes not slowly evolved over millennia of high times and hardship but bestowed upon the people through an act of divine intervention. The food comes with a set of rules, laws so sacred and unbreakable they may as well be etched on stone tablets. Thou shalt not overcook pasta! Thou shalt not mix cheese and seafood! Break them at your own peril. How dangerous is it to offend Italians over matters of the stomach? Just ask Nigella Lawson, domestic goddess of the British Isles, who innocently added cream to her carbonara recipe and watched the entire country rise up against her. Wrote one excitable defender of Italian heritage: “Nigella you are a wonderful woman but your recipes are the DEATH of Italian recipes, literally!”

If you need further proof of just how perilous the culinary waters can be in Italy, log on to Facebook or Twitter and search for the innocent prey of pasta zealots lurking in the e-shadows. The great Twitter account Italians Mad at Food documents the incensed reactions of the country’s eaters to the injustices perpetrated on their cuisine. A representative sampling: If you dare to serve that shit in Italy, you will be legally prosecuted and locked up in jail for life . . . Every time you put cream in a sauce, an Italian chef dies . . . We’re not just offended, we’re actually vomiting.

But the wrath is not felt only by foreigners. When Carlo Cracco, one of Italy’s most celebrated chefs, went on television and suggested adding garlic to amatriciana, the tomato-based pasta from the town of Amatrice in Lazio, an article appeared in La Repubblica, Italy’s largest newspaper, decrying the chef’s transgression. The polemic was dubbed the “garlic war” and took on the same sharp tenor typically reserved for political scandals. The mayor of Amatrice took to Facebook to deride Cracco’s blasphemous interpretation and reestablish the true recipe of amatriciana: “The only ingredients that compose a true amatriciana are guanciale, pecorino, San Marzano tomatoes, white wine, black pepper, and chili.”

Yes, other great cuisines come with their own unspoken rules, but no one is going to send you death threats if you dump wasabi in your soy sauce or put ketchup on your New York hot dog. In Italy, these are deeply personal matters. The offended employ not just words of shock or displeasure but violent imagery to articulate their outrage: the raping and pillaging and murdering of Italian culture.

Yet not even Italians can agree on the details of their most famous dishes. There is no one true recipe for any of Italy’s totemic regional plates: tagliatelle al ragù, agnolotti al plin, risotto Milanese, orecchiette alle cime di rapa, pasta con le sarde—all inspire endless debates about the “right way,” when in fact the right way is a series of choices—pancetta or guanciale, Parmesan or pecorino—not a fixed reality. But that doesn’t stop the defenders of Italian regional cuisine from passionately protesting every perceived transgression. Which, in its own way, is a beautiful thing. The fact that people—not chefs or food writers but your average Italian—care this much about details the rest of the world would dismiss as trivial is exactly what makes this cuisine so damn great. Allow cream into the carbonara, and next thing you know the barbarians will be feasting on your loved ones.

Of course, it’s not just the food. It’s cultural heritage, identity, history, and a boundless source of pride for everyone from the granite peaks of Piedmont to the sugared shores of Sicily.

The central figure at the heart of our understanding of Italian cuisine is la nonna, the battle-tested grandmother who for centuries has made tiny miracles out of the hands dealt to her by history and circumstance. In times of feast and famine, she always found a way to feed her family the fruits of the season, always found a way to make food special. It was la nonna who established the rituals and recipes of the Italian kitchen, who turned it into one of the world’s great cuisines, who helped perfect a formula that, in many minds, leaves little to no room for improvement. “In Italy, no cook is better than your grandmother.” It’s a sentence I hear so often that I begin to wonder if it doesn’t appear in Italian school textbooks. Italian food culture exists primarily at home, in the comfort of the family kitchen, but for those of us who don’t have a drop of Italian blood, we look for the next best thing: a sweet old woman in the back of the restaurant, making history with her hands.

If la nonna is the best cook, who needs a chef? If Grandma’s heirloom polpette are the best, who needs a modernized version? But what, then, happens when the grandmas are gone?

The easy answer is that a new generation of grandmothers will rise up and take their place at the crux of Italian culture, but women born after the war were raised in an entirely different Italy. Broadly speaking, these aren’t women who spent their formative years simmering sauces and mashing mortars and making pasta by hand; these were women making the gears of the Italian economy churn, who were lucky enough to make it home in time for dinner, let alone spend all day making it.

Cuisine, like all culture, is alive, and it’s always finding new ways to express its DNA. La cucina della nonna isn’t dead, but to define Italian food by what the oldest and most traditional practitioners cook is to deny the work being done across the country by thousands of ambitious cooks, young and old, female and male. From the mountain villages of Sardinia to the craggy coastline of Le Marche, everywhere you turn in Italy you see examples of a cuisine in a moment of great change—perhaps the greatest this country has seen since the aftermath of World War II, when a scarcity of resources forced cooks to find new ways to feed their families.

Martina Albertazzi

These aren’t radical changes, mind you. This isn’t Ferran Adrià working a Bunsen burner on the Costa Brava, changing food on a molecular level. To be sure, wildly inventive cuisine has found its way to certain corners of Italy—most famously with Massimo Bottura in Modena and Carlo Cracco in Milan—but the more enduring change is the slow, steady progression of a cuisine that neither needs nor wants a dramatic shake-up.

The tension between past and future is the through line that defines all modern Italian culture, and it’s the key to understanding the changes under way in the country’s cuisine. Individually, the cooks and creators behind this change have established outposts that blend tradition and innovation in a way that will help inform the future of Italian food. Collectively, the work they do is a resounding reminder to traditionalists and innovators alike that food is a living, breathing, constantly morphing organism. No one can stop its evolution, not even la nonna.

* * *

Marcus Gavius Apicius was a man of many appetites. He ate with relish the swollen liver of pigs fattened on diets of dried figs. Lamb crusted in exotic spices from far-flung worlds. Crests of roosters boiled directly from their still live heads, red mullet bathed in a fermented sauce made from its guts. Born around the time of Christ, he became the foremost foodie of the Roman Empire during the reign of Tiberius.

His cookbook, De Re Coquinaria, considered the world’s first, has become an important artifact for understanding Roman culture during the height of the empire. Apicius’s Rome was a place where exotic tastes from across the empire converged. Where extravagant feasts were blunt expressions of wealth and status. Where a nascent brand of experimental gastronomy pushed the limits of food and its role at the center of a global empire.

He embodied the most extreme expression of the ancient Roman appetite: a love of spice, of sauces and condiments, of products from the far reaches of the empire. He also embodied one of its most infamous qualities: boundless gluttony. In his final and most notorious act, the bankrupt Apicius decided to take his own life rather than go on without the wealth it would take to live the grandiose and exuberantly delicious life he craved—an eerie foreshadowing of the gluttony that would eventually bring the empire crumbling down three centuries later.

But beyond the extravagance of Rome’s wealthiest citizens and flamboyant gourmands, a more restrained cuisine emerged for the masses: breads baked with emmer wheat; polenta made from ground barley; cheese, fresh and aged, made from the milk of cows and sheep; pork sausages and cured meats; vegetables grown in the fertile soil along the Tiber. In these staples, more than the spice-rubbed game and wine-soaked feasts of Apicius and his ilk, we see the earliest signs of Italian cuisine taking shape.

The pillars of Italian cuisine, like the pillars of the Pantheon, are indeed old and sturdy. The arrival of pasta to Italy is a subject of deep, rancorous debate, but despite the legend that Marco Polo returned from his trip to Asia with ramen noodles in his satchel, historians believe that pasta has been eaten on the Italian peninsula since at least the Etruscan time. Pizza as we know it didn’t hit the streets of Naples until the seventeenth century, when Old World flatbread met New World tomato and, eventually, cheese, but the foundations were forged in the fires of Pompeii, where archaeologists have discovered 2,000-year-old ovens of the same size and shape as the modern wood-burning oven. Sheep’s- and cow’s-milk cheeses sold in the daily markets of ancient Rome were crude precursors of pecorino and Parmesan, cheeses that literally and figuratively hold vast swaths of Italian cuisine together. Olives and wine were fundamental for rich and poor alike.

But many of the dishes now seen as archetypal Italian cuisine didn’t come to the table until much later than we might believe—many are decades, not centuries or millennia, old, still warm from the oven. Take the curious case of spaghetti alla carbonara; now it’s a juggernaut of the Roman kitchen, but it didn’t surface on restaurant menus or in cookbook recipes until after World War II. And even though it’s so young, no one can say with any certainty where it comes from. Some believe it to have been a creation of the coal miners of nearby Abruzzo, the carbonari, who emerged ravenous from the mines to eat this spare but satisfying pasta. Others believe it was born out of American GIs’ nostalgia for bacon and eggs during the post–World War II reconstruction. And though the ingredients are few, the arguments abound: pancetta or guanciale, made from the pork jowl instead of the belly? Cubed or thinly sliced? Pecorino or Parmesan? Garlic or no? And then there’s the matter of the egg: a whole egg or just the yolk? Five or six ingredients but hundreds of possible permutations. The dish is young, enigmatic, and malleable—not qualities we typically associate with Italian cuisine.

I haven’t been around long enough to know new from old, so the first thing I do after the train pulls into Roma Termini is seek out the smartest cooks and eaters in the country and bombard them with questions: Is la cucina della nonna alive and well? How has the Roman kitchen evolved? Is Italian food getting better? I do nothing my first week but chew and listen.

The results of the informal survey, to say the least, are mixed. Some can’t even agree if Rome is a great eating city or not. “You know Rome’s food culture is the worst in Italy, right?” says Elisia Menduni, a journalist and author of various tomes on Italian cooking. Says who? I ask, smelling hyperbole on her breath. “Everyone.” According to Elisia, Roman cuisine is hampered by a lack of written history, a lack of a central thesis, by the scourges of tourism.

“People have been complaining about Roman food for twenty-five hundred years,” says Katie Parla, an American expat who fell in love with Rome in 2003 and has been writing passionately about its food ever since. (Her 2015 cookbook, Tasting Rome, is a gorgeous love letter to her adopted city.) “Rome has been a tourist destination for eating for over five hundred years. In the past fifteen years the way people eat, where they eat, how much they eat has been radically transformed by the economic crisis. People are drawn by quantity and the perception of value.”

Looking for the perspective of someone behind the line, I turn to Massimo Bottura, Italy’s most renowned chef, whose Modena-based Osteria Francescana was named the world’s best restaurant in 2016 by Restaurant magazine, the default arbiter on these matters. If anyone knows about the tension between the past and future of Italian cuisine, it’s Massimo. For years, Italians branded him a heretic for his subversive tipping of Italy’s sacred cows: tortellini in brodo, lasagne, Parmigiano-Reggiano. When I ask him if Italian food is getting better, he’s unequivocal: “This is the most amazing time to be a chef in Italy. The shackles have been thrown off! The country is creating incredible culinary talent.”

But opinions on food are like fingerprints in Italy. “I love Massimo and everything he does, but he is the capo of modern Italian cuisine. Of course he would say that.” The food writer Alessandro Bocchetti tells me this over lunch at Litro, a lovely osteria in the hilltop neighborhood of Monteverde, perched above Trastevere. We are eating warm bread slathered in cold butter and topped with salty anchovies, one of those three-ingredient Italian constructions—a shopping list more than a recipe—that can stop a conversation in its tracks. A cold bottle of malvasia gets the engine roaring once again. “Now is a difficult time for Italian cuisine. Young chefs are concerned with what’s in fashion, with flash and trends. But the Italian family still suffers from Italy’s deep recession.” His concerns aren’t with the restaurants at the top of the food chain but with those in the middle. “There are twenty restaurants today where you can eat as you never have before in Italy, but those are just twenty restaurants. The bigger picture isn’t quite so rosy.”

Ristoranti, the most formal class of dining in Italy, have the prices and the worldly clientele to experiment, but the heart of Italian food culture, especially Roman food culture, is the trattoria, an institution historically built on an infallible formula: good product, unfussy technique, reasonable prices. According to Alessandro, there are only a few true trattorie left in Rome, and he dispatches me to one with a friend, Andrea Sponzilli, another intrepid food writer. “He’ll know what to order.”

The one-and-only carbonara, a dish of endless debate.

Martina Albertazzi

Among the pillars of Italian cuisine, pasta is the most sacred—the one that has inspired thousands of books, millions of journeys, and infinite debates about the way to do it right.

The rest of the world openly wonders what makes Italian pasta so good and theirs so mediocre, but the answer is right in front of their faces: the pasta itself. The bond between flour and water (and in some cases egg) is sacrosanct, and it must not be broken unnecessarily, compromised by sloppy cooking or aggressive saucing or tableware transgressions. That means cooking it properly, ignoring package or recipe instructions and instead relying on a system of vigilant testing until only the barest thread of raw pasta remains in the center of the noodle. That means saucing it sparingly, in the same way a French chef might dress a salad, carefully calibrating the heft and the intensity of the sauce to the noodle itself. That means refraining from unholy acts of aggression: throwing it against the wall, adding oil to the boiling water, spinning the pasta against your spoon, or for God’s sake cutting the noodles with a knife and a fork. Above all, that means thinking not addition but subtraction, not what else can I add, but what can I take away?

Italian cuisine, at its very best, is a math problem that doesn’t add up. A tangle of noodles, a few scraps of pork, a grating of cheese are transformed into something magical. 1 + 1 = 3: more alchemy than cooking.

No strain of regional Italian cooking expresses that more clearly than the iconic pastas of Rome: gricia, carbonara, amatriciana, and cacio e pepe. “They are the four kings,” says Andrea as we peruse the menu of Cesare al Casaletto, a trattoria in Monteverde. It’s ten minutes from the center of Rome, but for tourists who rarely cross the Tiber except to dip a toe in Trastevere, it might as well be in Florence. Our table of four decides to divide the royalty among us, and when the four dishes of arrive, a silence falls over us. There’s a near-spiritual significance to having these four pastas on the table at once—each revered enough to have achieved canonical status among carb lovers the world over, but none containing more than a handful of ingredients.

Carbonara: The union of al dente noodles (traditionally spaghetti, but in this case rigatoni), crispy pork, and a cloak of lightly cooked egg and cheese is arguably the second most famous pasta in Italy, after Bologna’s tagliatelle al ragù. The key to an excellent carbonara lies in the strategic incorporation of the egg, which is added raw to the hot pasta just before serving: add it when the pasta is too hot, and it will scramble and clump around the noodles; add it too late, and you’ll have a viscous tide of raw egg dragging down your pasta.

Cacio e pepe: Said to have originated as a means of sustenance for shepherds on the road, who could bear to carry dried pasta, a hunk of cheese, and black pepper but little else. Cacio e pepe is the most magical and befuddling of all Italian dishes, something that reads like arithmetic on paper but plays out like calculus in the pan. With nothing more than these three ingredients (and perhaps a bit of oil or butter, depending on who’s cooking), plus a splash of pasta cooking water and a lot of movement in the pan to emulsify the fat from the cheese with the H2O, you end up with a sauce that clings to the noodles and to your taste memories in equal measure.

Amatriciana: The only red pasta of the bunch. It doesn’t come from Rome at all but from the town of Amatrice on the border of Lazio and Abruzzo (the influence of neighboring Abruzzo on Roman cuisine, especially in the pasta department, cannot be overstated). It’s made predominantly with bucatini—thick, tubular spaghetti—dressed in tomato sauce revved up with crispy guanciale and a touch of chili. It’s funky and sweet, with a mild bite—a rare study of opposing flavors in a cuisine that doesn’t typically go for contrasts.

Gricia: The least known of the four kings, especially outside Rome, but according to Andrea, gricia is the bridge between them all: the rendered pork fat that gooses a carbonara or amatriciana, the funky cheese and pepper punch at the heart of cacio e pepe. “It all starts with gricia.”

And that’s where I start, lifting the pasta from the big-bellied bowl and marveling at its humility: nearly naked, with only the faintest suggestion of human interference. To truly enjoy a pasta of this austere simplicity is to surrender yourself entirely to the scope of its achievement: How to extract so much from so little? How many ingredients in any other cuisine around the world would it take to create a dish as satisfying as this one? Why doesn’t my pasta taste like this?

You could argue that the two central ingredients at the heart of Rome’s pasta culture aren’t really ingredients at all: the first is water. Not just any water, but the water used to cook all those batches of pasta throughout service, each successive batch of noodles leaving behind a layer of starch that steadily transforms the water into an exquisite binding agent, perfect for adding to a pasta sauce to adjust the consistency and clinginess.

The other vital ingredient in the Roman pasta canon is a simple but vital technique: a flick of the wrist, the aggressive movement needed to emulsify the cooking water with the fat in a pan of pasta sauce. By swirling the pan with one hand and using a set of tongs with the other to keep the starch in constant motion, like a Cantonese chef taming the breath of the wok with a hand that never stops moving—what Italians call la mantecatura—a thirty-second mating ritual of intense amorous energy wherein pasta and condiment become one. Without water and without the wrist motion, cacio e pepe would be nothing more than pasta dressed with cheese and pepper, gricia would be noodles in a mess of rendered pork fat. (Of course, most non-Italian cooks don’t even attempt this delicate dance, opting instead to go the route of poor Nigella, adding cream to their carbonara and cacio e pepe.)

The Cesare specimens are among the finest I’ve tasted. Using rigatoni instead of spaghetti for carbonara would evoke an avalanche of angry Facebook posts from pasta purists, but there’s no doubt that the hollow shape makes a more generous home for the silky sauce. The gricia is deserving of its fame across the city, the toothsome strands of housemade tonnarelli robed in a soft blanket of warm pig fat and pecorino. And the cacio e pepe, well, let’s just say the cacio e pepe will follow me everywhere across this country in the months to come, a three-ingredient measuring stick for the greatness of Italy’s regional cuisine. Albert Einstein said he saw the possibility of a higher power in the harmony of the natural world; some find it in the magnificent complexity of the human body. I see it in the miracle of cacio e pepe.

Before the hushed reverence of our pasta moment threatens to turn lunch awkward, the sound of happy eaters snaps us out of our silence. “The story of Roman cuisine is the story of the neighborhood restaurant,” says Andrea. “Any real romano will always believe the best osteria is next door. Their loyalty is always to the neighborhood.” You can feel that loyalty in the room today: parents linger over dessert as their kids play under the table, old couples hold hands as they finish off the last few sips of wine. Maybe some have made the trip from other parts of Rome—it’s certainly worth it—but chances are that most live within strolling distance.

After a lineup of stellar secondi—braised tripe, fried lamb chops, veal braciola simmered in tomato sauce—Andrea and I wander into the kitchen to talk with Leonardo Vignoli, the man behind the near-perfect meal. Cesare al Casaletto had been a neighborhood anchor since the 1950s, but when Leonardo and his wife, Maria Pia Cicconi, bought it in 2009, they began implementing small changes to modernize the food. Eleven years working in Michelin-starred restaurants in France gave Leonardo a perspective and a set of skills to bring back to Rome. “I wanted to bring my technical base to the flavors and aromas I grew up on.” From the look of the menu, Cesare could be any other trattoria in Rome; it’s not until you twirl that otherworldly cacio e pepe (which Leonardo makes using ice in the pan to form a thicker, more stable emulsion) and attack his antipasti—polpette di bollito, crunchy croquettes made from luscious strands of long-simmered veal; a paper cone filled with fried squid, sweet and supple, light and greaseless—that you understand what makes this place special.

Ask a nonna why she does something in the kitchen—why she cuts the vegetables a certain size or why she uses red wine instead of white in the ragù—and you’re likely to get a shrug. That’s the way I was taught, and that’s the way I’ve always done it. Leonardo, on the other hand, does everything with an intense sense of purpose. He shows me the embers gently hissing in the brick oven for the roasted meat, the big-bellied, wide-rimmed bowls that keep the pasta warmer longer, the shimmering olive oil in the fryer, already changed out in anticipation of the dinner service.

“We are still a trattoria,” says Leonardo. “We still serve the same dishes most others do. We still charge the same prices. We just put a little more thought into the details.”

Few people put more thought into the tiny details than the team behind the ever-expanding Roscioli empire, one of the nerve centers of the cucina romana moderna, found just a few steps from the Campo de’ Fiori. Sitting at a small table inside the Ristorante Salumeria Roscioli, a hybrid space that functions as a deli counter in the front and a full-service restaurant in the back, general manager Valerio Capriotti tells me with conviction that Italian food is flourishing—advancing in ways it hasn’t in years, if ever, thanks in large part to the efforts of small producers who put their lives into raising rare breeds of pig, growing heirloom varietals of wheat, and milking pampered dairy cows and sheep to create the types of ingredients that drive restaurants like Roscioli forward. “Modern Italian cuisine isn’t about technique,” he tells me, “it’s about ingredients. We know more now than we ever did about how things are made and what they do when we cook and eat them.”

Exhibit A: the Roscioli carbonara. The pasta comes from a small artisanal maker in Abruzzo, the guanciale from pampered local pigs, the eggs from the rock-star farmer Paolo Parisi in Pisa, and the black pepper from Malaysia. Every single ingredient is the best in its class, but in the end, it’s still a carbonara: no seasonal vegetables, no innovative garnish, no games played with temperature or texture—a beautiful reminder that restraint may be the most important ingredient in the Italian larder.

Exhibit B: the Roscioli burrata. In a world oversaturated with half-hearted burrata dishes, Roscioli serves up a category killer. Again, the brilliance comes down to the sourcing—in this case, from a small cheese maker in Andria, the heart of Puglia’s burrata culture. Try it with semidried cherry tomatoes, an explosively sweet-and-sour counterpoint, and squares of Roscioli’s habit-forming pizza bianca, and you’ll realize you’ve probably never tasted real burrata before.

Ristorante Salumeria Roscioli is not a traditional trattoria. The menu is full of eccentricities, some successful (rigatoni with bottarga and yuzu butter), some less so (Camembert consommé with fried fish), but the philosophy behind its best dishes (the cheese, charcuterie, and classic pastas) is what matters: subtle, persistent advancements in the few areas where improvement is still possible. “The evolution of cooking is about accumulating wisdom and using it when needed,” says Valerio. “We take lessons from nonna, but we adapt them for a more contemporary perspective.”

But the ethos that made Roscioli into one of the most influential institutions in Rome, if not all of Italy, doesn’t end with carbonara and charcuterie. It doesn’t even start there. Antico Forno Roscioli isn’t exactly new—it opened in 1824, almost four decades before Italy became a country. But the work of its latest leader, Pierluigi Roscioli, and his team have turned the bakery into a brilliant bridge between past and future. He makes Rome’s finest pizza bianca (which should be eaten early and often during a Rome stay) with organic, heirloom wheat and bakes heroic breads with ancient grains long out of favor in the country’s bakeries: kamut, spelt, and rye from Trentino. “Bread is a pure expression of raw ingredients,” says Pierluigi. “It’s not about technical advancement.”

Antico Forno Roscioli, redefining Roman baking for generations.

Martina Albertazzi

Not content with rethinking bread, cheese, and pasta, in 2016 the Roscioli crew brought its philosophy to one of the most immutable pillars of the Italian culinary forum: coffee. Roscioli Caffè, a few doors down from their other ventures, does a lot of special things, from its next-generation pastry display to the modern cocktails and antipasti they serve in the evenings, but the real innovation is in the caffè they serve every day to hundreds of busy Romans.

Italy didn’t invent coffee, of course (that distinction belongs to the Ethiopians, who began boiling coffee cherries a millennium ago), but they did invent café culture and with it a set of unspoken rules as rigid as the ones that govern the food world: no milk after 11 A.M., no takeout, no tongue-twisting requests for skinny this or caramel that.

In the same way that Italian cuisine has been largely resistant to the whims of modern fads in the kitchen, Italian coffee culture has scarcely changed since 1884, when Angelo Moriondo presented his blueprint for the espresso machine at the General Exposition of Turin. While the rest of the world cycles through “waves” of coffee (FYI, we’re currently on the Third Wave, marked by an increase in bean quality, technical brewing advancements, and overall snobbery), Italy remains happy to do caffè (espresso is rarely used in Italian coffee parlance) the way it’s always done it.

Popular belief has it that you can’t find bad coffee in Italy; sidle up to a bar anywhere in this country, from a tiny southern village to a gilded urban institution to a highway gas station, and you’ll be treated to an espresso or cappuccino of extraordinary quality. Though it’s true that the average coffee you drink in Italy is better than what you find elsewhere in the world due in large part to the ubiquity of gorgeous, expensive espresso machines—and the presence of talented baristas everywhere who know how to play those machines like orchestral instruments—the quality of what comes dribbling out of those machines has been steadily declining over the years. Italy’s espresso economy is dominated by giant coffee producers (Lavazza, Illy, Segafredo), which maintain a stranglehold on the market by providing everything from branded machines and signage to napkins and coffee cups in exchange for long-term contracts guaranteeing the use of their espresso beans. Though Segafredo is leagues better than, say, Folgers or Bonka, it’s still an industrial coffee product that can’t compete with the quality of small-production, single-origin beans that form the heart of modern coffee culture in Tokyo, Stockholm, and San Francisco.

Turin (the home of Lavazza) and Trieste (the home of Illy) host Italy’s highest concentration of coffee institutions, old-school bars hermetically sealed off from outside trends. But Rome isn’t far behind. Places such as Antico Caffè Greco, La Campana, and Caffè Eulalia make good caffè, and are perfect pit stops for refueling during a long day wandering across the city, but all serve the same species of dark, hard-roasted, bitter espresso with little to no variation.

Beyond a generally high standard of quality, two characteristics define Italy’s coffee culture: speed and low price. Italians might drink five espressos a day, and they want them to be both fast and affordable. The latter is so critical that the government regulates the price of espressos and cappuccinos.

So no, don’t expect to find an Italian paying $5 for a pour-over coffee that takes ten minutes to make and twenty to drink. But at Roscioli Caffè, Salvatore Cerasuolo and his team of well-dressed baristas have been quietly incorporating the best of modern coffee principles and folding them into the rhythms of a traditional Italian caffè. “Italian coffee culture is five hundred years old,” he says. “Over the years, there’s been an explosion of commercialization and automation across the industry. Part of that means the raw materials aren’t always great.” In a world defined by speed and ease, Salvo obsesses over the finer details: the age of the coffee bean, the height at which it was grown, the subtle differences of the temperature and length of its extraction. “All of these elements are slowly getting better in Italy,” he says. Salvo sources his coffee from Laboratorio di Torrefazione Giamaica Caffè, Italy’s premier small roaster, a Verona-based operation that eschews the dark, oily roasts that are standard across the country in favor of a lighter, more subtle coffee bean. You won’t detect notes of strawberry and passion fruit in your cappuccino; this is still assertive Italian coffee, but with more nuance than you’ll find at the corner spot.

If Salvo looks like the moody barista at your neighborhood coffee shop in Brooklyn (crisp white button-up, black suspenders, black handlebar mustache), that’s because Italy invented the dapper, dedicated barista. But don’t expect a lecture on water temperature or a grimace when you ask for sugar. Salvo and his crew will happily make you a V60 pour-over or a batch of coffee brewed in the glass curves of a siphon, but in a dozen mornings of sipping cappuccinos at Roscioli’s gorgeous bar, I saw not a single filtered coffee ordered. No siphon swirls, no long, slow savoring of a Chemex coffee. Instead, it’s caffè and cornetto, cappuccino and brioche con panna, the customers coming and going so quickly that they barely break stride as they mainline the caffeine. The clients at Roscioli probably don’t know the difference between shade-grown and sun-grown coffee, between Panama Geisha and Guatemalan Bourbon, but they come here because the combination of old and new makes for the best caffè in Rome. And that’s what counts.

* * *

Not every change is so subtle. There are chefs in Rome taking the same types of risks other young cooks around the world are using to bend the boundaries of the dining world. At Metamorfosi, among the gilded streets of Parioli, the Columbian-born chef Roy Caceres and his crew turn ink-stained squid bodies into ravioli skins and sous-vide egg and cheese foam into new-age carbonara and apply the tools of the modernist kitchen to a create a broad and abstract interpretation of Italian cuisine. Alba Esteve Ruiz trained at El Celler de Can Roca in Spain, one of the world’s most inventive restaurants, before, in 2013, opening Marzapane Roma, where frisky diners line up for a taste of prawn tartare with smoked eggplant cream and linguine cooked in chamomile tea spotted with microdrops of lemon gelée.

At Retrobottega, not far from the constant churn of Piazza Navona, a crew of young chefs have taken their years of staging at the temples of high Italian cuisine and unleashed their accumulated skills in a decidedly downscale environment. Diners sit at the bar or a series of high tables, pull out their own silverware from drawers, fetch and open their own wine, and collect plates from the pass as the chefs call them out from the open kitchen. Regardless of how you feel about chatting with line cooks or playing server to yourself, the payoff comes on the plate: zucchini and anchovies in a tart scapece with pureed mushrooms; fried chicken hearts, scattered across the plate like popcorn and cut with little curls of pickled vegetables; and a plate of linguine aglio e olio, one of Italy’s staple pastas, tricked out with a pool of grana fondue below the tight nest of noodles.

To taste some of the more radical transformations, you’ll need to travel farther afield, beyond the swaths of mediocre restaurants that clog up the city’s central arteries. On an unsuspecting residential block in Centocelle, a working-class neighborhood on the outskirts of Rome, a tiny restaurant with a single communal table and a chalkboard menu on the wall is pushing the classic notion of a casual neighborhood eatery. Every night, it fills up with locals and foreigners, pasta freaks, and gastro geeks all partaking of a rare and exceptional take on modern Roman cuisine.

The husband-and-wife team Marco Baccanelli and Francesca Barreca are known as “the Fooders” among Rome’s culinary cognoscenti, a nickname they earned during years of catering and pop-ups in the run-up to opening Mazzo. “It gave us time to tweak, to play with new ideas,” Francesca tells me late one afternoon before dinner service. A group of young Italians crowds the front patio, sipping Spritzes. Down the table from us, a beautiful blonde takes alternating drags off a book of poetry and a glass of pinot grigio. “We love food, but we love music, design, art, and we want to find ways to bring it all to our restaurant.”

The result has made the duo into one of Rome’s culinary power couples. It takes but a few minutes to spot the synergy between Francesca and Marco—they crack jokes, debate new ideas, and finish each other’s sentences. “He’s the grandma in our kitchen,” Francesca says, gently elbowing her husband. “He’s here making pasta by hand every day, like a good nonna, but we’re always thinking of new ways to cook it.”

Beyond being the foundation of so much of Italy’s cooking, the grandma plays a central role in the Italian culinary psyche. “Nonna cuisine has a definite cultural value, both for Italians and for foreigners,” says Marco. All else being equal, would you rather see an eighty-year-old woman in a worn apron or a thirty-five-year-old man with a long beard and a tilted Yankees cap rolling out your tortelli? For his part, Marco relishes the chance to challenge stereotypes. “Every batch is different,” he says with a mix of enthusiasm and consternation, “but I’m especially excited about how it came out today.”

Dinner starts with a ceviche of beef, the love child of northern Italy’s raw beef culture and the couple’s interest in assertive flavors from around the world. Depending on the day, you may find lemongrass, cilantro, and miso—perfect strangers across Italy—canoodling with cured anchovies and handmade pastas. “It’s not fusion,” says Francesca. “We don’t ever think ‘How can we work a bit of Asia into this plate?’ If it makes sense on the fork, then we go for it.”

From there Francesca takes me through the entire menu: from the esoteric and unexpected—fried snails over a dashi-spiked potato puree, glazed pork belly with cavolo nero kimchi—to gentle riffs on the soul food you’d find in a traditional trattoria—fried artichokes dipped into an anise-spiked mayonnaise, tender pork sweetbreads with tiny candy-sweet asparagus and a slick of Mazzo’s exceptional olive oil. “Roman cuisine isn’t frozen in time,” says Francesca in one of our midmeal exchanges. “We don’t have any set way we come up with dishes—sometimes they grow out of tradition or a dish we ate while traveling. Other times, a single ingredient.”

Francesca and Marco, aka the Fooders, stand tall at Mazzo.

Alfredo Chiarappa

Marco’s rigatoni finally emerges, wearing a meaty, fatty, unapologetically aggressive ragù. The pasta it clings to, cooked to the outer edge of al dente, would make the most battle-tested nonna proud.

To my right are three middle-aged Italians deep in conversation about Roman politics. To the left are a religion writer from Washington, D.C., and her husband, decked out in a button-up Hawaiian shirt, who found their way out here on the recommendation of a journalist friend. Both seem amused by their presence at a communal table in Centocelle, as if they’re not quite sure how they keep ending up at these hip restaurants. Francesca comes out of the kitchen to talk to all the diners, introducing herself in Italian and English and asking everybody about the food. When she makes it to the couple, the pescatarian wife looks up with cabernet eyes and a Parmesan smile. “That was an interesting ceviche dish. What kind of fish was that?” Francesca looks nervously at me, and I tell the woman gently that it wasn’t fish at all. She takes it with a smile, and Francesca relaxes.

“Well, it was a lovely meal,” the writer says, swirling the last of the wine in her glass. “But it didn’t feel very Italian.”

* * *

Ancient Rome was one of the world’s first street food cultures. With one million residents packed into a space now occupied by a tenth of that number, the cramped quarters left little room for personal kitchen space. To cook at home meant building a fire, a dangerous proposition with so many souls packed in so tightly. Instead, an economy of casual food cooked on street corners and sold to the masses took shape: flatbreads, grilled sausage, fried fish.

Over the centuries, Rome shed its sardine-can concentration of inhabitants, but the presence of handheld snacks persisted. Panini, tramezzini, fried mozzarella, the crunchy rice snacks known as supplì: the Roman love of carbs, cheese, and meat arranged in various expressions knows no bounds.

The king of these expressions, here and everywhere in Italy, is pizza. Not the round, blistered, knife-and-fork pizzas of Naples, but pizza of a different shape and stature: thin, light, crispy, portable. Glistening gold rectangles of pizza bianca have long been a street snack powering Rome: crunchy and tender, bitter from a slick of olive oil and sweet from the slow browning of grains, with shards of coarse salt that explode in your mouth at random intervals. Some eat it hot out of the oven; others slice it and fill it—with mortadella, prosciutto and figs, anything you might find on an antipasto plate.

But even the simplest, most sacred foods need updating. One of the chief catalysts of pizza’s recent evolution is Gabriele Bonci, virtuoso bread man, who set off a small revolution in the Italian baking and pizza world years ago when he opened Bonci, a small outpost on the far side of the Vatican where you’ll find a dozen varieties of pizza, sold by weight and changing daily, if not hourly. It’s easy to be taken in by Bonci’s ambitious flavor combinations—mortadella with a chickpea puree, grilled octopus and bitter greens—but the real innovation, the one that stirred a lot of soul-searching in a pizza world resistant to change, comes down to the dough itself. Bonci works with small producers growing ancient varietals of grains, which form the base of his high-hydration, long-fermented dough—crispy, tender, and gently sour, a masterpiece of complex flavors and contrasting textures. Leave the raw porcini, grilled beef, and smoked salmon to the Instagrammers; the best stuff at Bonci are the slices that show off Bonci’s grain work, simple, sober displays of craftsmanship: pizza rossa with a thin blanket of crushed tomatoes and floral drifts of oregano; pizza Margherita made with half a dozen different combinations of mozzarella and tomato; and the pizza con le patate, a carb-on-carb affair possessed of an impossible lightness of being.

If Bonci is the “Michelangelo of pizza,” as some have dubbed him, Stefano Callegari is the pizza world’s Willy Wonka, delivering waves of shock and delight to people who have spent their entire lives eating the same slices. Callegari grew up in Rome’s Testaccio neighborhood, working at a bakery, making pizza bianca for the local clientele. After a fifteen-year stint as a flight attendant for Alitalia, he finally grounded himself and set about constructing a new world of dough and cheese. At Sforno, the pizzeria he opened in Cinecittà in 2005, he mastered the basics but also began to explore new frontiers. Combinations such as headcheese and Campari or Stilton with a port reduction caused a stir in the Roman pizzarazzi, but the big breakthrough came with his pizza cacio e pepe, a feat of technical wizardry that involves baking the dough with chipped ice on its surface, creating enough residual moisture to hold the pecorino and pepper in place.

But here, in his restaurant Trapizzino on his home turf in Testaccio, he took the genre bending a step further. Using a newspaper, sugar packets, and animated hand motions, Callegari reenacts the creation of the Trapizzino, a pocket of crispy dough that eats like the love child of pizza and tramezzino, Italy’s triangular sandwich. Skeptics might see in the Trapizzino the sad pizza cone found on food trucks in the United States and beyond, but this is no half-hearted gimmick: crispy and tender, light but resilient, it is an architectural marvel of pizza ingenuity. Not content with traditional pizza toppings, Callegari instead ladles slow-cooked stews of meat and vegetables—tongue in salsa verde, pollo alla cacciatora, artichokes and favas with mint and chili—that perform magnificently against the crunch and comfort of this warm pizza pocket. “The best of old Roman cooking is like great ethnic food—slow-cooked, humble ingredients with big flavor.”

“Yes, it’s about the ingredients, but it’s a cook’s job to transform those ingredients into something special.” Callegari has since expanded his Trapizzino vision to the United States (New York) and Japan (Tokyo and Kyoto) and plans to open more, but the Testaccio shop, the one flooded by a constant flow of the young and hungry, is the nerve center of his pizza genius.

Testaccio makes a fitting home for a shape-shifting pizzeria; on the banks of the Tiber, just southeast of the city center, it’s the neighborhood that best represents the modernizing face of Roman culture. Once home to the municipal slaughterhouse, one of the largest in Europe, and the blue-collar citizens who kept it running, the neighborhood has undergone the type of transformation that replaces the old and the static with the young and the restless. Testaccio still clings to a piece of its humble former self, but when Eataly, the massive high-end Italian market, took over an old train station at the edge of the neighborhood, it was only so long before the fixed bikes showed up to do battle against the cobblestones.

The Testaccio Market anchors the neighborhood, an esoteric collection of commercial merchants, ambitious food and wine purveyors, and casual food shops. You can eat a slice of pizza, shop for shoes, pick up a dozen long-stem artichokes, have a straight-razor shave, and wash it all down with a bottle of biodynamic pinot grigio. Market dining may be standard fare in cities around the world, even in other parts of Italy, but when Testaccio Market reopened in 2012, it was a new style of eating for the romani. (In the years since, the concept has caught on and spread across the city.) There are a dozen places to eat, from crispy, four-bite pizzette to soup and sandwiches from Michelin-starred chef Cristina Bowerman, but you’re really here for Mordi e Vai. Sergio Esposito worked as a butcher in the neighborhood, where he had been a promoter of quinto quarto, Rome’s legendary offal culture—named for the idea that the viscera is “the fifth quarter” of the animal. Esposito’s earlier career gave him an idea: What if we took the intense, rib-sticking offal stews and braises of the neighborhood and turned them from knife-and-fork fare into sandwiches?

Thus the quinto quarto panino was born. Today you’ll find Esposito and his crew stuffing soft rolls with slow-cooked honeycomb tripe, coratella (braised lamb innards) and artichokes, and fegato alla macelleria, butcher-style liver with tomatoes and caramelized onions. The best of the bunch, allesso di scottona, is an old-school braise of beef brisket, best when topped with a thicket of sautéed chicory and an extra ladle of the cooking juices. They’re edible monuments—to Testaccio before its transformation, to the Jewish ghetto, the source of so many of Rome’s greatest dishes—many slowly finding their way off the endangered species list thanks to people like Esposito and Callegari.

A Trapizzino trio in Testaccio.

Matt Goulding

Beyond being superlative street food, Esposito’s sandwiches solve two persistent challenges: they give a new life to classic Roman dishes that had fallen out of favor and turn the normally prosaic panino—a sandwich housing a lonely slice of prosciutto or a lifeless wad of mozzarella—into something worth standing in line for.

In an extra layer of innovation, Esposito turned to the classic pasta sauces of Rome for inspiration, stuffing panini with his riffs on amatriciana and cacio e pepe and a pepper-bombed carbonara spiked with chunks of veal. Imagine la scarpetta, the Italian ritual of scraping the bottom of a pasta bowl with hunks of bread, in sandwich form, and you get an idea of Esposito’s genius.

Of course, more than pizza cones and tripe sandwiches, the most ubiquitous street food in Rome is gelato. It’s also one of the Italian pillars most in need of reinforcing. Despite the museum-worthy beauty of so many of Rome’s central gelato spots, the trend for decades has been moving away from natural ingredients and toward prefab concoctions and chemical-laden mixes riddled with emulsifiers, stabilizers, and food coloring. Artfully displayed garnishes—clusters of hazelnuts, swooshes of Nutella, rainbows of fresh fruit—are a red herring, a cheap and easy way to pull in clientele with the appearance of handmade quality.

But a countermovement has been taking shape for years, prompted by those looking to keep gelato from losing its soul entirely. Claudio Torcè is one of the godfathers of Rome’s gelato resurgence, whose opening of Il Gelato di Claudio Torcè in 2003 helped establish a set of new standards: local, seasonal ingredients, refined techniques inspired by high cuisine, and the embrace of esoteric, overlooked, and counterintuitive flavors. At his mother ship in EUR, on the southern edge of the city, he offers one hundred flavors daily, many only vaguely suggestive of dessert (Parmesan, habanero, mortadella), but all defined by a minimum number of ingredients and a maximum expression of flavor. Anyone can fashion ice cream out of a funky ingredient and wait for the world to react; only masters like Torcè can make it delicious.

In the end, the good ones are more gelato chefs than gelato makers, dedicated to doing whatever it takes to concentrate as much flavor as possible into a single cold bite. Few embody this idea more thoroughly than Marco Radicioni at Otaleg in Colli Portuensi. From the street, a glass-walled laboratory packed with gadgets announces Radicioni’s ambition to passersby: this isn’t an old man in the back hand-churning gelato from today’s batch of vanilla; this is a man driven by the idea that there’s always a way to make something a little bit better.

True to its name (gelato spelled backward), Otaleg is swimming against the tide of cost-cutting convenience that dominates Italy’s ice cream industry. Sixty flavors at a given time, rotating daily—most rigorously tied to the season, many inspired by a pantry of savory ingredients: mustard, Gorgonzola with white chocolate and hazelnuts, pecorino with bitter orange. He seeks out local flavors, but never at the expense of a better product: pistachios from Turkey, hazelnuts from Piedmont, and (gasp!) French-born Valrhona chocolate. Extractions, infusions, experiments—whatever it takes to get more out of the handful of ingredients he puts into each creation. In the end, what matters is what ends up in the scoop, and the stuff at Otaleg will make your toes curl—creams and chocolates so pure and intense they must be genetically manipulated, fruit-based creations so expressive of the season that they actually taste different from one day to the next. And a licorice gelato that will change you—if not for life, at least for a few weeks.

Radicioni and Torcè are far from alone in their quest to lift the gelato genre. Fior di Luna has been doing it right—serious ingredients ethically sourced and minimally processed—since 1993. At Gelateria dei Gracchi, just across the Regina Margherita bridge, Alberto Monassei obsesses over every last detail, from the size of the whole hazelnuts in his decadent gianduia to the provenance of the pears that he combines with ribbons of caramel. And Maria Agnese Spagnuolo, one of Torcè’s many disciples, continues to push the limits of gelato at her ever-expanding Fatamorgana empire, where a lineup of more than fifty choices—from basil-honey-walnut to dark chocolate–wasabi—attracts a steady crush of locals and savvy tourists.

But don’t expect the rest of Rome to suddenly follow suit, especially if you like to get your gelato fix within melting distance of a gladiator or a famous fountain. There are hundreds of gelaterie in Rome today, and very few dispense the real stuff. Why pay the money and spend the time to do it right when your onetime customer, never to be seen again, doesn’t know the difference? It’s a cynical equation, but it’s the same math that has converted Times Square, Las Ramblas, and other tourist-dense pockets the world over into culinary black holes.

They’ll continue to open packages and dispense prefab gelato dressed to impress. And the people will continue to eat it up. Because, like sex and pizza, even when gelato is bad, it’s still pretty good.

But life’s too short for average ice cream. In the end, there are a dozen ways to explain why the gelato at Otaleg or Torcè or Fatamorgana is better—the ingredients! the laboratories! the creativity!—but there is an even simpler explanation, the same one at the heart of all great food: because its creators care more than everyone else does.

* * *

Over the weeks in Rome, the old and the new begin to bleed together, and I struggle to pull them apart. Maybe it’s the impossible history, the one that paints every street corner with a mix of tragedy and promise. Maybe it’s the rivers of olive oil, the puddles of pork fat, the snowdrifts of grated cacio that gather in my blood. Maybe it’s the bottle of Dr. Schulze’s THC drops that my friend Alessandro gifts me upon my arrival in Italy (“Add a few to your pasta, and you’ll see Italy in an entirely different way!”). The world begins to wobble.

I am supposed to be going to Italian class to sharpen my skills before the long march across the country, but I can’t bring myself to sit down. Distracted by the morning market in Campo de’ Fiori, where the colors of the countryside—purple crowns of asparagus, orange-lipped squash blossoms—shine with hallucinogenic intensity; by the sounds of Italy caffeinating itself, the low drone of the espresso machine, the clank of the cappuccino cup as it lands between glass plate and metal spoon; by the promise of another meal, good or bad or indifferent, around every corner, another glimpse under the veil. What classroom could compare to the city at large?

Instead, I wander. Past the bones of an empire scattered across the cityscape, peeking through parks, crowding the street corners, rubbing up against shiny buildings that reflect the sunlight. Through the hills of Monteverde, where Rome opens up like an artichoke past its prime. Along the streets of Trastevere, where every cliché of Italian life unfolds so vividly you wonder if Disney isn’t holding the strings: old woman in her window observatory, sharing secrets with the neighborhood; mustachioed man perched on a stool, peeling porcini in the shadows. Art and life become indistinguishable, an imitation game that goes around in stunning circles.

SPQR: Sono Pazzi Questi Romani. These Romans Are Crazy.

I start to dream of cacio. Not daydream, not wonder lustily when my next bite of salty sheep’s-milk cheese will come, but deep REM visions of cacio in every texture imaginable: resting delicately above a plate of pasta, browning into a crispy shell on a flattop griddle, turned into a tea with kernels of black pepper bobbing on the surface. Cacio e pepe: black and white like a Fellini film, this speckled union follows me everywhere across Rome—into the crunchy supplì at La Gatta Mangiona; onto the pizza at Tonda; smothering a burger at Luppolo Station, a dive bar on the outer edge of Trastevere—a burger so impossibly good that I return the next night to eat it again, to make sure I wasn’t dreaming. (I wasn’t.)

I keep going back to the same places, to Roscioli for a morning cappuccio and an afternoon burrata; for slices of pizza bianca from Bonci, which I fold like a letter home I keep forgetting to send and devour; to Mordi e Vai and Trapizzino, where they send me out to the streets with handheld poems to Rome’s past.

I follow a bread-crumb trail to other tastes of a Roman future: to Open Baladin to drink in Italy’s staggering craft brew scene, a freewheeling counterpoint to the country’s well-established wine world; to Emma, where I eat pizza so thin and crunchy it nearly vanishes before I have a chance to chew. Every time I stray from the path and choose a place for its beauty, the city extracts a price: a bad bowl of pasta, a sad scoop of gelato, a lifeless puddle of espresso, precious space wasted.

Consistency was never a strong suit in Rome. The city is at turns austere and extravagant, luxurious and shabby, regal and bohemian, deadly serious and surprisingly playful. Eternal and fleeting. When you’ve lived as many lives as Rome has, you’re allowed to be malleable.

Armando al Pantheon is located just a few steps from the namesake monument, in what might qualify as the least likely place in Rome to find an exceptional restaurant. I stumble into the kitchen one morning and ask for the owner, Claudio Gargioli. One of his daughters is whipping eggs for tiramisù. His other daughter, recently graduated from culinary school, works the burners with a handful of pans that form the base of the restaurant’s pasta game. Artichokes are in various stages of undress across the kitchen. An older man peels the thistles down to their core before dropping them into a bath of boiling olive oil; they emerge in golden brown bloom minutes later. A younger man works his own batch, stuffs them with a single garlic clove and a bay leaf, adds a few inches of water to the bottom of the pan, covers it, and sets it on a burner before going on to the next prep item. It’s hard to imagine a more honest kitchen than the one buzzing before me.

The Pantheon, still standing after millennia of misfortune.

Alfredo Chiarappa

Claudio looks up when he sees me at the kitchen threshold. “You mind if I finish this pan of guanciale before we talk?”

Claudio’s father, Armando, opened the restaurant in 1961, and throughout the 1970s and ’80s, Claudio cooked alongside his family, taking an ever stronger role in the food. “I wanted to do pure Roman food e basta. That meant focusing on a few things: seasonal ingredients, a few great pastas, quinto quarto.” The only point that everyone I spoke with in Rome agrees upon is that Armando al Pantheon is one of the city’s last true trattorie.

Given the location, Claudio and his family could have gone the way of the rest of the neighborhood a long time ago and mailed it in with a handful of passable pastas and a stash of fresh mozzarella and prosciutto. But he’s chosen the opposite path, an unwavering dedication to the details—the extra steps that make the oxtail more succulent, the pasta more perfectly toothsome, the artichokes and favas and squash blossoms more poetic in their expression of the Roman seasons.

“I experiment in my own small ways. I want to make something new, but I also want my guests to think of their mothers and grandmothers. I want them to taste their infancy, to taste their memories. Like that great scene in Ratatouille.”

I didn’t grow up on amatriciana and offal, but when I eat them here, they taste like a memory I never knew I had. I keep coming back. For the cacio e pepe, which sings that salty-spicy duet with unrivaled clarity, thanks to the depth charge of toasted Malaysian peppercorns Claudio employs. For his coda alla vaccinara, as Roman as the Colosseum, a masterpiece of quinto quarto cookery: the oxtail cooked to the point of collapse, bathed in a tomato sauce with a gentle green undertow of celery, one of Rome’s unsung heroes. For the vegetables: one day a crostino of stewed favas and pork cheek, the next a tumble of bitter puntarelle greens bound in a bracing anchovy vinaigrette. And always the artichokes. If Roman artichokes are drugs, Claudio’s are pure poppy, a vegetable so deeply addictive that I find myself thinking about it at the most inappropriate times. Whether fried into a crisp, juicy flower or braised into tender, melting submission, it makes you wonder what the rest of the world is doing with their thistles.

At the end of service on my last night in Rome, Claudio comes out of the kitchen beaming, a man who lives to feed people. We talk about pasta, about the little moves that make his so memorable. We talk about the wrist action that a good Roman cook needs to do a proper carbonara or gricia. We talk about the importance of pasta water, the unsung hero of the Roman kitchen, how it gets better as service wears on, the starchy ghosts of noodles past turning the boiling water into a murky spa of magical powers.

More than a deeply talented cook and convivial host, Claudio’s a scholar of Roman cuisine. He can speak eloquently about the dual roles of the Jews and the pope in influencing Roman cuisine, about the slow evolution of the city’s pasta culture, about the future. If anyone knows where food is going around here, it’s Claudio. “Innovation is a beautiful thing, as long as we never forget our roots.”

I leave Claudio and step out into the Roman night. The broad shoulders of the Pantheon wait for me just around the corner. It looks eternal in the golden night glow, a temple built to honor the gods back when the Romans believed in more than one. But it fell twice since then—burned first in A.D. 80, in a great fire that engulfed much of the city. Thirty years later, it was struck by lightning, brought to its knees by a bolt from the sky. War and weather, time and temperament: all have taken their toll. Yet here it is, standing strong, just a block from the kitchen where Claudio makes his cacio e pepe with peppercorns from a far-off land.

That’s the beautiful part of the story of Rome, the story of Italy: You don’t erase the history. You build on top of it.