Vito Dicecca has made mozzarella in thirty-three countries. He made it in Australia, two weeks after arriving, just eighteen years old and looking to devour the world. He took a job in a kebab shop, grew restless with the towers of spinning meat, and instead sought out his people: cheese makers. He found them not far away on a dairy farm making French-style cheeses with goat’s and sheep’s milk, but he couldn’t find anything that looked or tasted like home. So he showed them home: fist-size balls of mozzarella, taut and shiny and fresh as a newborn. He made mozzarella in Thailand, on Ko Pha Ngan island, out in the middle of the Gulf of Thailand. It was the night before the island’s infamous Full Moon Party, and with time on his hands, he befriended a local, who introduced him to a buffalo farmer, who provided him with the milk to weave brilliant braids of the cheese of his homeland, and just as the sun set and the full moon rose and boatloads of drug-addled travelers descended on Haad Rin beach for their taste of the apocalypse, Vito and his new friend sat on the sands, enjoying warm slices of Thai buffalo mozzarella with leaves of purple basil. He made mozzarella outside Phnom Penh, Cambodia, with a farmer who had always dreamed of making cheese with the milk of his herd of water buffaloes. Vito traveled to his farm on the back of a motorbike, and the two made mozzarella, burrata, and fresh yogurt. Later they took their creations down to a local children’s hospital and gave samples to the young patients, and the kids and the farmer and the cheese maker from Italy shared a taste of authentic Cambodian buffalo mozzarella.

Paolo Dicecca has made mozzarella in twenty-one countries. He first made mozzarella in Phuket, Thailand, where the abundance of island buffaloes provided the milk for a perfectly respectable version of burrata, a combination of shredded mozzarella and fresh cream wrapped in a thin skin of mozzarella, which Paolo sold to the tourist-crushed island’s smattering of Italian restaurants. He made mozzarella in Michoacán with a Mexican farmer who had everything he needed to make cheese—expensive machinery, milk—except the knowledge. Today, Michoacán has a source of first-rate Mexican mozzarella. In 2015, Paolo traveled to Ivory Coast to make cheese. He saw an industrial brand of mozzarella on sale in a supermarket for an astronomical price, and he wanted to show the people of Africa that real mozzarella can be made for very little. In a village he found cows with perfectly good milk, and though he had to pasteurize it due to the heat and the hygiene, Paolo made cheese he remembers as being some of his best. Pictures from the trip show the young cheese maker on a dirt road in a village, smiling widely, surrounded by young children all reaching for a taste of Italy.

Angelo Dicecca has made mozzarella in twenty-five countries—from Argentina to the South Pacific to the iron heart of Manhattan. The most improbable mozzarella Angelo ever made didn’t happen on a tropical island or in an African village but in Santa Marca, Colombia, at his ex-girlfriend’s house at one in the morning. They had been drinking, partying, enjoying the kind of slow-burning night that seems to stretch on for days in South America. She wanted to dance; he wanted to make cheese. “Let’s just say that it came out . . .” he trails off, his mind taking little nibbles of that early-morning mozzarella, “. . . artisanal.”

The Brothers Dicecca: Angelo, Paolo, and Vito.

Alfredo Chiarappa

Vito, Paolo, Angelo: the brothers Dicecca. They roam the earth like bounty hunters, possessed by one simple idea: where there’s milk, there’s mozzarella. It has driven them everywhere—from countryside to cityscape, from the far Far East to the tip of South America, more than sixty different countries in total—in an unwitting effort to show the world that good mozzarella is more about craft than country.

But for all their itinerant cheese adventures, Vito, Paolo, and Angelo, along with their sisters, Maristella and Vittoria, make and sell mozzarella primarily in one place: Altamura, Italy, a hilltop town on the western edge of Puglia.

Altamura isn’t the most beautiful town in Puglia—that distinction would go to Lecce, home of the famous limestone used to construct an endless labyrinth of piazzas and churches and impossibly perfect wine bars, or Otranto, the same ancient limestone architecture spread out dramatically on a shelf above the crystalline convergence of the Ionian and Adriatic seas. Both bear the mark of Magna Graecia, the Greek settlement that dominated southern Italy from the time of the Trojan War through the dawn of the Roman Empire and that still echoes throughout Puglia today—in the stone pillars, local dialects, and humble coastal cooking that define the region.

It’s not even the most beautiful town in the near vicinity. Matera, twenty-three kilometers west on the edge of Basilicata, is a Roman town with deep scars from bygone eras of poverty and starvation. But now it is best known for its neighborhoods of ancient caves built directly into the side of a ravine, one of the most majestic destinations in this most majestic of countries.

In most regards, Altamura is a perfectly normal midsize town perched on a hill fifty kilometers southwest of Bari, Puglia’s capital—safely removed from the brilliant beaches that attract throngs of well-oiled domestic sunhounds to the region every summer. There are a hulking, thirteenth-century cathedral, a clearly demarcated old town and new town, an open-air market for produce and protein, and a thirsty population of young college students who flood the streets on the weekends.

There are two things that almost everyone in Italy knows about Altamura: First and foremost, il pane di Altamura, a thick-crusted, swollen-domed semolina loaf, bronzed and built to last, one of the most revered breads in Europe and the first in Italy to be designated with Denominazione di Origine Protetta (DOP) status, one of the highest designations for food products in Europe. At all hours of the day, the town smells of campfires and toasted grain.

The second piece of Altamura lore that made this town a known quantity across Italy is the short, unhappy life of McDonald’s. When the Golden Arches arrived here in 2001, it had its detractors, but Altamura largely accepted its presence as the cost of upward mobility in a modernizing world. It opened right on the edge of Altamura’s old city, where some locals found jobs and many more found a spot for the occasional hamburger. But as the months wore on, the tide turned against Ronald and his clown posse. Locals began to view the Arches as an attack on their culture—one defined by time and tradition, not speed and convenience. When the chain erected a giant neon M that cast its sinister yellow glow in the shadow of the giant cathedral, the citizens of Altamura mobilized.

They fought back the only way they knew how: with food. Community leaders organized events to highlight local foods—the cured meats, breads, and cheeses of Altamura. Businesses ran counterattacks by offering anti-McDonald’s specials on their edible goods. In the most aggressive offensive, Di Gesù, the town’s most famous bakery, opened an outpost directly adjacent to McDonald’s, serving warm, freshly baked focaccia for less than the plain hamburgers sold next door.

“What took place was a small war between us and McDonald’s,” Onofrio Pepe, a retired journalist, told the New York Times in 2006. “Our bullets were focaccia. And sausage. And bread.”

Those weapons, including no small amount of hand-stretched mozzarella, ultimately vanquished the burger-slinging Goliath. Two years after it opened its doors, the fast-food juggernaut quietly packed up its things and got the hell out of town—a victory for the artisans, traditionalists, and serious eaters of Altamura.

But Altamura has something else that no other town in Puglia or the whole of Italy has: la famiglia Dicecca. Vito, Paolo, and Angelo, the mozzarella masters, who along with Maristella and Vittoria, run Caseificio Dicecca, one of the greatest cheese shops in a region built on the back of great cheese shops.

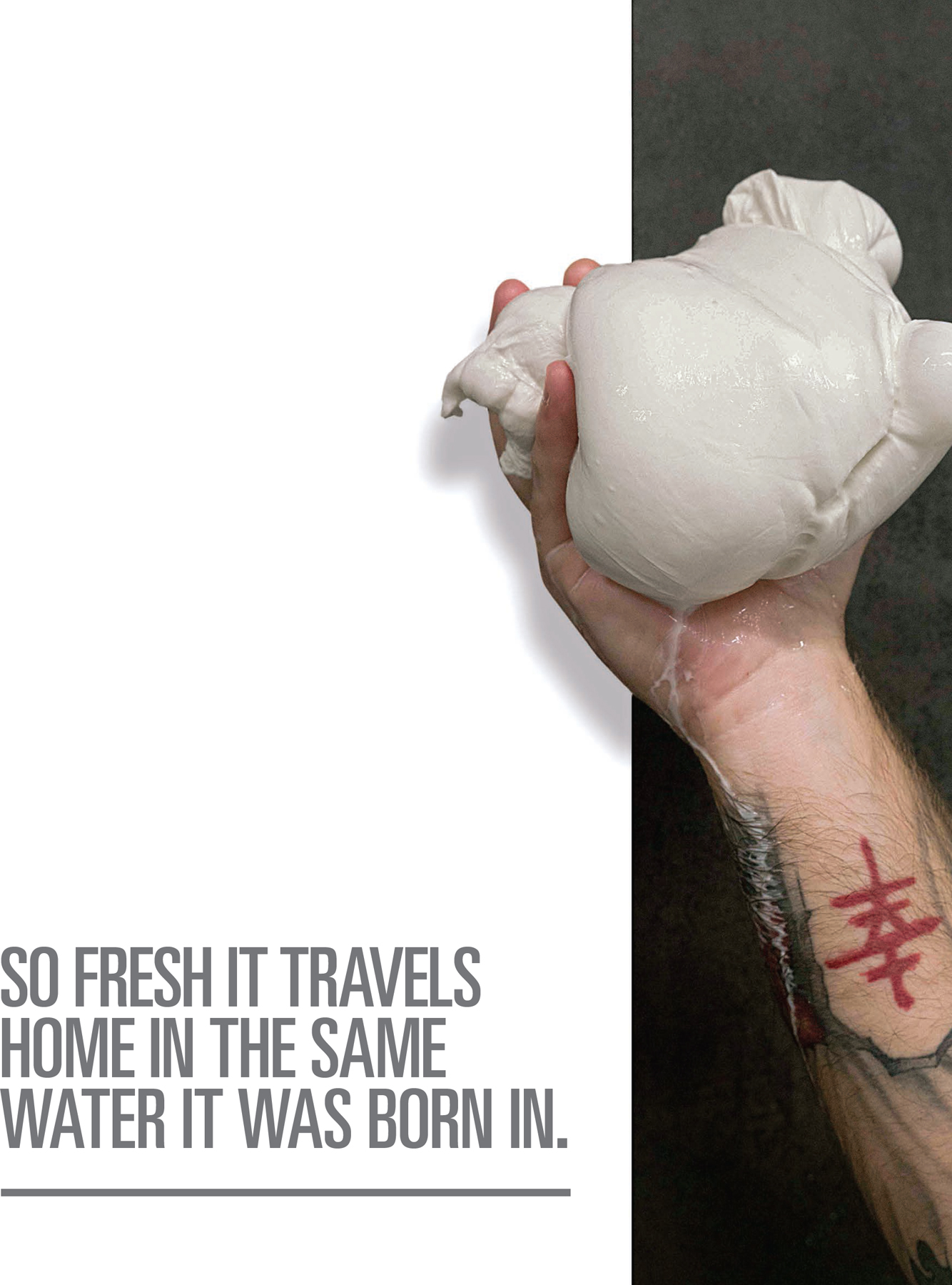

The tip of Italy’s boot is one sprawling lactic fantasy, a sparsely populated landscape filled with cows and buffaloes, sheep and goats, where the average citizen consumes 23 kilos of cheese a year—more than any other region in Italy. Not just salty, funky pecorinos and firm cow’s milk cheeses such as caciocavallo but a different class of cheese entirely: fresh cheese made every morning in any of the 318 caseifici (producers and vendors of cheese) that dot this flat coastal landscape—cheese still warm from production, sold from glass display cases a few paces from where it’s made, so fresh and fragile it travels home in the same water it was born in.

Cheese in most parts of the world is either a luxury or an afterthought—an indulgence that we allow ourselves to eat in small portions at specific moments or a condiment added as a postscript to a sandwich, an omelet, a salad. In Puglia, cheese is neither a treat nor a topping; it’s a fundamental part of the region’s DNA, right down to the double-helix braid of the mozzarella. In fact, they don’t even call the types of cheese consumed here cheese—they call them latticini, products made with milk and eaten fresh. Some of the fiercest food fights I’ve seen have been between southern Italians and unsuspecting eaters insisting that mozzarella is formaggio.

Whatever you call it, the closest relation to the latticini of Puglia is bread, something that you buy daily, that you consume quickly and constantly, that finds its way effortlessly to the table at nearly every meal. Fittingly, the production of the fresh cheeses of Puglia closely mirrors the making of bread—elemental in its base, endlessly complex in its execution—a culture that employs thousands of people across the region that spend each day making and selling cheese that will be gone by tomorrow.

And like bread, the cheese of Puglia is born before most of the world has begun to stir.

* * *

6:05 A.M.

Be there at 6 man. My brother waits for no one.

The text message came in from Vito overnight. But the only person to be found on the streets of Altamura at this hour is an older, heavyset man dressed in a white apron seated on the stone steps beside the cheese shop.

When he sees me coming, he shrugs his shoulders. “I don’t know. They should be here. But they’re kids, you know?” Then he pauses, looks down at his hands, reconsiders. “They’re not that young. I mean, they’re adults now. They should be here.”

Michele Saliano has been making cheese in Altamura since 1980. For many years, he had his own shop down the street, but competition in this town is stiff, and making and selling cheese are two different skill sets. Still, years later, Michele can’t speak about his failed business without a wistful glaze in his eyes. “It was a beautiful store. All the equipment was new. Bellissimo.”

It’s 6:15. Still no sign of the fratelli Dicecca. Michele and I talk about cheese, the one love I know we share. “It’s not easy. You watch people make it, and it might look easy. But it’s not.” The hardest part? “Il latte. Learning to control the milk. In a caseificio like this one, a real caseificio, the milk is different every day.”

A BMW pulls up, and out spill three young men in various states of slumber. They say nothing, walk dead-eyed directly into the bar across the street, and mainline espresso.

Properly caffeinated, Vito, Paolo, and Michele open the work area in the back of the shop and begin to prepare for the day’s production. Angelo and I have a different mission: We load into the Dicecca milk truck—mounted with a long, silver tank with a 1,500-liter capacity—and drive into the countryside. Normally, Salvatore Dicecca—papà Dicecca—drives the truck out of Altamura at dawn to collect the milk for the day, but just weeks earlier, he had an accident on the job and he’s been sidelined—temporarily or permanently, no one can say.

Matt Goulding

Angelo is filling in as milkman today. By the time the spires of the cathedral of Altamura vanish, the caffeine puts an end to Angelo’s prolonged silence. “Everything starts with the milk. I’ve been working with milk since I was ten years old. It takes a lot of passion and a lot of patience to build your life around milk.”

Angelo, thirty-seven, is the oldest of the five siblings, and the first to venture beyond Altamura. With his thick, shoulder-length locks, wraparound sunglasses, and white Dicecca polo with the constantly popped collar, he looks like a yacht deckhand who may or may not be sleeping with the owner’s trophy wife. He takes selfies constantly, even while driving, especially with a reporter and his notebook riding shotgun. I smile nervously, eyeing the trees and gullies flashing by inches from the window.

“I left home when I was twenty. Went straight to Phuket. My parents thought I’d be scared and lonely and that I’d be back in four days. But I kept traveling.” Nearly two decades later, and he’s helped establish a global network of cheeseheads, some of whom he revisits, all of whom he keeps up with through social media while planted back in Puglia. “The point isn’t just about cheese; it’s about exporting our culture.”

I tell Angelo that I have three older brothers and that despite my fondness for them I can’t imagine spending twelve hours a day together in confined spaces. He shrugs his shoulders. “It’s what we do. It’s what we’ve always done—work as a team. As the oldest, I try to set a good example, but there’s no boss. We’re all equal partners in this business.”

Thirty minutes outside Altamura, in the heart of the Alta Murgia National Park, down a long tree-lined dirt road, we come upon the Didonato Farm, ground zero of Dicecca cheese. The Diceccas have been buying milk from the Didonato family for more than sixty years. Vito Didonato, the newest in the line of family dairy farmers, keeps a small herd that feeds off the dense flora surrounding the farm. “That’s the difference between our milk and everyone else’s.”

The tank half filled, we climb back into the truck and head to a second farm—smaller, tucked right into the edge of a small village—for a top-off. “These are the two best farms in the region. We go to both because we want the right balance of fat and acidity in the milk. In the end, it gives us a more interesting product.”

Latticini like those produced by the Diceccas aren’t static creations; they are expressions of the Pugliese terreno from one day to the next. In the late spring, when the fields grow thick with flowers and herbs, the milk takes on hints of thyme and wild oregano. Come winter, when the rains soak the surrounding area and the herd feeds off a blend of dried cereals, the milk is fattier, less aromatic. It’s those subtleties Angelo or his dad or whoever else gets behind the wheel of the Dicecca milk truck chases each morning.

“Most cheese makers in Italy don’t have their own trucks. They make a phone call, and the milk suddenly appears. But I’m not in the office, making calls from a desk, relaxed. I’m up early in the truck, taking risks.”

One could argue that in a modernized food system, the milk wrangling is superfluous—that the cheese will still be the cheese regardless of how the milk travels, that the customers don’t care if the latte came from a massive truck making the daily rounds or a family-owned vehicle driven by Angelo just as the first espresso is setting in.

As we ride from one distant farm to the next, I crunch the numbers. It starts innocently enough—the corner cutting. Too expensive and time-consuming to fetch the milk yourself? Pay the farm to deliver it, and if the one that grows its own grass and herbs can’t do it, find one that will. Margins on that local sheep’s-milk specialty too thin to justify? Strike it from the board, along with that aged goat cheese that takes too much time and space to make. Suddenly, who needs the hands of a human to shape mozzarella when a machine can do it twice as fast at half the cost? In the world of craftsmanship, compromise is always a slippery slope.

“I love it, but it’s hard work,” says Angelo. “I’m tired. We’re all tired. My fantasy is that one day a Chinese businessman will make his way to Altamura and offer us ten million euros for the caseificio. It needs to be ten because there are five of us and we each need two million to survive.” He grows quiet afterward, eyes fixed on the road, as if he’s spending all that cash already. “With two million, I’d buy a farm outside Belo Horizonte in Brazil. Two cows, two goats. I’d make cheese two or three times a week—never to sell, just for me and my friends.”

7:36 A.M.

By the time we pull the truck up to the side door of Caseificio Dicecca and run a hose from the gleaming milk tank to the massive stainless steel vat inside, Vito, Paolo, and Michele, the old cheese maker I met on the steps this morning, are deep into the day’s production.

Across the five-hundred-square foot working space, in industrial mixers and plastic tubs, in shiny steel baths and hard-plastic buckets, the journey from liquid to solid is well under way. Milk is manipulated into every possible texture and temperature: salted and scalding hot, cool and au naturel; thin and transparent, partially coagulated, in mountains of dense and crumbly curds, in thick ivory ropes ready to be stretched and shaped. To the outside observer, it’s almost impossible to follow the various permutations of protein and fat, curds and coagulants, liquids and solids and squishy, weepy in-betweens.

Milk is a miracle. By its very nature, it’s a complete nutritional package, a ready-built diet with a pitch-perfect balance of fat, protein, and carbohydrates that can sustain mammalian life indefinitely. This same package of macronutrients makes it ripe for manipulating—butter, yogurt, cream. And, of course, milk’s most magnificent expression: cheese.

Cheese making is one of human’s earliest acts of culinary manipulation, stretching back some four millennia to the times of Chinese warlords and Egyptian pharaohs. It started as a rudimentary product, more an accident than a conscious creation. Civilizations as diverse as the Sumerians and the ancient Chinese used animal stomachs to transport food, including milk, only to discover that the rennet in the stomachs acted as a natural coagulant—spontaneously creating something close to cottage cheese. The ancient Romans were the ones to elevate cheese making to a fine art. Pliny the Elder, one of history’s most voracious and astute gourmands, chronicled the variety of cheeses produced across the expanse of the empire—from the cow’s-milk cheeses of the Alps to the sheep cheeses of Liguria. (By Pliny’s estimation, a smoked goat cheese made in Rome itself was the finest cheese of its day.)

The great cheeses of Europe were born during the Middle Ages—Cheddar in southern England in the twelfth century, Gouda in the Netherlands not long after; Parmigiano-Reggiano, the king of Italian cheeses, emerged as a staple of the cuisine of Emilia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. From there, cheese began its inexorable march toward diversification, from sharp, funky blue cheeses aged in caves to unpasteurized triple creams to tangy pucks of goat cheese rolled in lavender and fennel pollen. By some estimates, more than four thousand varieties of cheeses are produced today—a thousand in France alone—made from a dozen different kinds of milk: cow, sheep, yak, reindeer, even human.

Italy’s cheese culture is as diverse and hyperregionalized as the rest of its food culture. In the far north, in Val d’Aosta, cheeses such as fontina and toma more closely mirror the high-mountain cheeses of Switzerland and France. In Sardinia, where sheep outnumber humans, pecorino predominates—found in dozens of expressions, including the infamous casu marzu, the maggot-covered sheep’s-milk cheese still considered a delicacy in certain parts of the island. But these are very different cheeses from the ones that dominate the caseifici of southern Italy. The Diceccas work in the cheese family known as pasta filata—stretched or pulled cheeses, a reference to the technique used to form this class of soft, fresh cheeses. Pasta filata is the dominant form of cheese making across Puglia, where before refrigeration the warmer climate reduced cheese’s shelf life from months to a matter of days.

Behind the daily transformation of milk into cheese is a science that could fill a grad school syllabus. For the sake of sanity, yours and mine, I’ll give you the short, simplified version: Milk becomes cheese through a process of coagulation, splitting milk into two core ingredients: liquid whey and solid curd. To coagulate milk, producers add a souring agent (mostly yeast, but sometimes vinegar or even other cheese) and rennet, an enzyme that helps form stronger curds. The curd is the base of which all cheese is formed: you can serve it straightaway as fresh, light cheeses such as ricotta and formaggio fresco or extract more liquid and compress the curds to make harder, more assertive cheeses that can stand up to aging.

To make stretched cheeses such as mozzarella, cheese makers submerge the curds in near-boiling water, then use large wooden paddles to stir, mix, and eventually stretch the amorphous mass, working the long protein strands the same way a baker does when she kneads a ball of dough. This action gives mozzarella both its elastic texture and its exceptional meltability.

No matter how big or small the cheese operation, production begins with the curd (called cagliata in Italian), the only difference being the quality of the curd. The brothers use a fresh cagliata, made with the day’s milk delivery activated with natural yeast and rennet. It sits in the center of the room, piled high on a stainless-steel table, a living, breathing bridge between raw ingredients and an artisanal product. The brothers hack away at the mountain throughout the morning, cutting custardy slabs off to initiate each new batch of cheese. But these days handmade cagliata is becoming more and more scarce in cheese making. “It’s too easy to buy a German curd that they’ll deliver to your doorstep for pennies,” says Angelo. “But you can taste the difference immediately.”

The Diceccas typically start each day with around 1,500 liters of cow’s milk, which will be transformed into mozzarella in at least five different shapes and sizes, from nodini, small one-bite knots, to treccine and nodi d’amore, bulky braids of mozzarella weighing up to a kilo. Beyond that, they’ll make burrata, ricotta, and straciatella. A separate supply of goat’s milk and sheep’s milk is used on odd days to create a handful of the Diceccas’ specialty products—including Don Vito, a pecorino modeled after the recipe first developed by the boys’ grandfather, plus a few of the cheeses that set them apart from other regional caseifici.

Today is Tuesday, which means they make pecorino from 800 liters of sheep’s milk on top of the normal production schedule. By the end of the morning, the three brothers plus Michele will have made ten different types of cheese—more than 200 kilograms, the majority of which will sell before the sun sets tonight.

8:05 A.M.

The day’s first customer waddles through the front door, an older woman with a small cart ready to be filled with the morning’s grocery haul. From now until 8:30 P.M., minus an extended break in the middle of the day, as in any upstanding Italian business, not a minute will pass without the arrival of a new customer. In the back, the four cheese makers continue their delicate dance of scalding and stretching while the sisters attend to the steady drip of locals.

The Caseificio Dicecca is a fourth-generation operation, started by the brothers’ great-great-grandfather in 1908. In 1930, the shop opened in its current location, a small storefront on Via Bari, a few blocks from the stone archway that leads into Altamura’s historic center. For most of the life of the caseificio, the Dicecca family has lived in the apartment above the shop.

At first glance, the main display case at Dicecca today looks like a selection you’ll find in any cheese shop in Puglia: tubs of milky water covering hunks of mozzarella in its many guises; strings of swollen scamorze dangling from the ceiling, bronzed by their stopover in the cold smoker; small plastic containers of creamy ricotta ready to be stuffed or spread or eaten straight with a spoon. But look closer and you’ll see some unfamiliar faces staring back at you through the glass: a large bucket brimming with ricotta spiked with ribbons of blue cheese and toasted almonds, served by the scoop; a wooden serving board paved with melting slabs of goat cheese weaponized with a cloak of bright red chili flakes; a hulking wheel of pecorino, stained shamrock green by a puree of basil and spinach. These are the signs of a caseificio in the grips of an evolution, one that started more than a decade ago as the brothers took the reins from their parents and began to expand the definition of a small, family-run cheese shop.

Alfredo Chiarappa

For three generations, that family-run shop produced the same selection of cheeses you find in shops across Puglia: mozzarella in various shapes and sizes, burrata, ricotta, pecorino, caciocavallo. Today, Caseificio Dicecca is home to dozens of ingredients that previous generations of Diceccas wouldn’t have recognized: chocolate from Venezuela, whiskey from Japan, smoked paprika from Spain. But the cheeses that Vito, Paolo, and Angelo create aren’t errant experiments by a pack of wild-eyed youths; they are edible tales from their travels, of the people they met and the tastes they discovered along the way. This is the other side of the Dicecca brothers’ vision: to bring mozzarella to the world and bring the world to mozzarella.

Vito emerges from the back with a new stack of cheeses that he arranges in the case like a kid setting up for a science fair. Bushy beard, backward hat covering an aggressive shock of strawberry blond hair, arms wallpapered in tattoos documenting his travels, Vito could double as a roadie for Metallica. He first started making cheese when he was six years old, when he would wander down from the family’s apartment to help his grandfather shred the cheese to make stracciatella. “It’s like a language or any other skill—it’s best to learn to make cheese when you’re young.” None of the Dicecca boys took to the classroom—Vito least of all. He dropped out at twelve years of age, told his parents he was done with formal education, spent his teenage years making mozzarella and mistakes in equal measure, and at eighteen left Altamura with nothing but a backpack and a one-way ticket to Australia.

As the ancient adage goes: If you know how to tend bar, cut hair, or make cheese, you can find work anywhere. Vito spent the next five years wandering the world, from the sparkling beaches of the Gold Coast to the mountains of New Zealand and up through Asia, to the islands of Thailand and the pulsing urban centers of Japan. The cheese and the travels worked in tandem, one informing the other—he wanted to see more of the world, and mozzarella became the vessel through which he experienced it. Eventually he turned west, trekking through California before crossing the border into Mexico. He made mozzarella in southern Mexico, on the Yucatán Peninsula, on the gringo-packed shores of Playa del Carmen, where he grew tired of lying on the sand and soaking up the scenery and decided, as he always did, to find a way to make mozzarella. It was there, somewhere between the lapping waves of the Gulf of Mexico and the mozzarella-devouring guests at the hotel he worked at, that Vito had a revelation: “I saw that teaching people to make mozzarella meant I was doing something good for the world. But I wanted to do something good for my family and for me.” It was time to go home.

He wasn’t going back alone, though. He had in his head a scrapbook of the tastes that had impacted him the most during his travels: goat cheese and olive oil in California, the tropical fruits and chilies of South America, everything that had touched his lips in Japan. When Angelo and Paolo talk about their travels, they turn to the memories—the parties, the people, the crazy times had, always with the metronome of mozzarella beating in the background. But what followed Vito were the flavors—the dishes, ingredients, and techniques unknown to most of Italy.

“When I came back from Japan, there were six kilos of matcha, two kilos of coconut powder, and twelve bottles of Nikka whiskey in my bag. In Rome they stopped me and they opened the bag. They thought they had caught me with cocaine. I told the guy to open up the bag and taste.”

Vito didn’t drink that Nikka (he and his brothers rarely drink alcohol); instead, he emptied all twelve bottles into a wooden bucket, where he now soaks blue cheese made from sheep’s milk to make what he calls formaggio clandestino. He stirs a spoon of high-grade matcha powder into Dicecca’s fresh goat yogurt and sells it in clear plastic tubs, anxious for anyone—a loyal client, a stranger, a disheveled writer—to taste something new.

Vito uses these flavors as a way to both hold on to the past and share it with others. When he proposed to his girlfriend, a German woman he met through the travel service Couchsurfing (he’s the chief host in Altamura), he didn’t do it with champagne and strawberries; instead, he soaked a heart-shaped blue cheese in red wine, covered it in cranberries, and paid a server to deliver it to his dinner table.

In the side refrigerators, where Vito so carefully arranges the morning’s new attractions, you’ll find even more examples of a traditional caseificio gone rogue: a wheel of aged goat cheese coated in a rough armor of wild herbs; a thick, blue-veined goat cheese soaked red with purple with Primitivo wine; goat yogurt in half a dozen international flavors.

You won’t be surprised to find that the early efforts of the Dicecca boys were met with opposition—both from the family and the regular clientele. Each brother has a story about the resistance he has encountered along the way—the parental eye rolling at the cacao-coated goat cheese, the sisterly skepticism about mango-stuffed burrata, the customers’ confusion at the latest experiment to emerge from the lactic laboratory in back. Every story ends the same way: with one or all of the family members doubting the viability of another esoteric cheese, followed by the long, slow acceptance by enough customers to justify its real estate space in the display case.

“When I started making cheese with the Nikka barrel, they made fun of me, said I was destroying the taste of the cheese. Now they’re copying me. That’s the pattern we always see: at first they make fun, then they start to copy.”

If the making of the cheese is handled by the Dicecca brothers, the selling is captained almost exclusively by Maristella and Vittoria, the Dicecca sisters. They know nearly every customer by name, have their orders committed to memory, so that the conversations they have during this brief little window of the day are more personal than transactional. You seen Leo’s new car? Madonna! How’s your brother recovering from his hip surgery? When are you going to invite us over for dinner?

Vittoria cuts a strong presence behind the counter, both sweet and accommodating but unwilling to take bullshit from anyone, especially her brothers. As the face of the business, the sisters walk a careful balance between supplying their loyal clientele with the cheese they know and love and finding the moments to push their siblings’ more far-flung lactic adventures. If a client takes a small step toward the unconventional—say, the chili-spiked goat cheese—Maristella might offer a taste of the wild side, say a spoon of whiskey-soaked blue cheese.

Their own stance on the extreme cheeses is something closer to tolerance than encouragement, but even that has its limits. “Vito, stop playing with the cheese! Get back there and make ricotta!” Vito, now taking photos of the creations on his phone, appears unmoved by the protestations. It’s hard to tell how much of the back-and-forth represents true tension or is just playful ribbing—the pugliesi, like the napoletani, are masters at straddling the line between genuine consternation and playful provocation. Unthinkable in Milan or Bologna, where appearances are maintained and decorum endures, most of this takes place in plain view of the gathered clientele, who not only are unfazed but from time to time participate in the back-and-forth. This, after all, is southern Italy, where lives are led publicly, where a ball of burrata can be a window into someone’s world.

When sales slow, Maristella makes a run at her hourly whip cracking on the brothers. When she makes it back, I squeeze in a question before the next customer—if all this sibling exposure wears on her. “Yes, my brothers can be a pain in the ass,” she says, turning to a customer. “But I love this job. What else could I ask for?”‘

9:04 A.M.

When everything is firing, when the milk becomes curd and the team hits a groove and the morning melts away, the rhythm of mozzarella making takes on a musical quality: the light splash of hands breaching the hot water, the muted thump of wooden paddle against stretched curd, the baritone kerplunk of knots and braids of flying mozzarella landing in a salt bath across the room. The hiss of hot water rushing out of the hose. Close your eyes, and you can imagine the long, methodical buildup of an experimental jazz joint that never takes full form.

The men work in silence, save for when one of the brothers calls me over to show me something: the twist of the wrist needed to make perfect one-bite nodini; a piece of mozzarella fashioned into an elephant. Paolo is especially proud of his lactic sculptures, and he wants to make sure I’m capturing every inch of his oeuvre with both camera and pen. “Matteo! Come over here! You see this!” He poses with dairy braids and mozzarella animals, turning toward the street until both he and the cheese sparkle in the morning light pouring through the open door.

Paolo, the middle brother, used to spend the summers as a kid in the back of the shop with his father and grandfather stretching cheese. “They had me doing nodini—my little hands were perfect for tying the small knots.” He dropped out of school at thirteen and went to work at the caseificio—the first of the siblings to officially take up cheese making in a formal capacity. “There were a lot of different cheese makers who passed through the shop, and I learned something new from all of them.”

But a cheese shop in Altamura can start to look tiny to a twenty-year-old with a curious mind, so Paolo stuffed all the lessons he’d learned into the bottom of a backpack and hit the road. He spent a lot of time in South America and found himself falling for a bit of everything: Colombian chocolate, Brazilian beaches, Venezuelan women. If he came to a town or a city with a reliable source of milk and a decent Italian restaurant, he had all the ingredients for a pop-up mozzarella business. “It’s a lie when people tell you you can only find good mozzarella in Italy. Bullshit. If you find good milk—with good fat and good acidity—and you work it well by hand, it can be every bit as good anywhere in the world.”

Paolo loved the adventures as much as his brothers did, but he was anxious to get his hands back into the scalding waters of the caseificio. He views his role at the caseificio as an unspoken contract, a promise to repay the lessons taught by his father and grandfather by writing the next chapter of the Dicecca cheese story. “My parents are exhausted. They made a lot of sacrifices to make this shop work. We do well now, but it wasn’t always like that. My father used to ride his bike to get the milk, a ten-year-old with two containers of milk. Now what does a ten-year-old do? Not a damn thing.”

While his brothers handle ricotta, caciocavallo, pecorino, and the bulk of the cheese experiments, Paolo works almost exclusively on mozzarella, which makes up the lion’s share of production at Dicecca. The large spheres we’re used to seeing are only one expression of mozzarella—you’ll find at least six others at Dicecca, all made from the same base, all slightly different in size and shape and therefore use in the everyday lives of the pugliesi. Bocconcini might find their way into a salad, nodini be plucked straight from the fridge for a midafternoon refuel, and the more dramatic and substantial braids be saved for platters put out when guests arrive.

Alfredo Chiarappa

Those summers tying mozzarella knots as a boy paid off for Paolo; his shaping skills are unrivaled in the family. His braids are tighter, his spheres both plumper and lighter. Whereas Angelo and Vito can look lost in a daydream at certain points during the morning’s production, Paolo’s attention never turns from the hot water and cagliata before him. On the Dicecca’s Facebook page, you’ll find videos of Paolo turning long ivory ropes of stretched curd into massive meters-long braids. “Every maker leaves his mark,” he says, running his finger across the cheese’s seam. “Look at the difference between Michele’s and mine. When you buy mozzarella, you want to see the mark of human hands on the cheese.

“You need to treat mozzarella like a girlfriend—gently, but with confidence. See this,” he says, motioning to a dozen little white spheres bobbing in the water, “see how light and delicate it is? It doesn’t sink in the water, it floats on the surface.” When Paolo talks about the importance of working water into the cheese, it’s because he’s not after a dense, fatty mozzarella; he wants a light product, easy to eat and easy to digest—not an occasional indulgence but an integral part of the daily diet.

The most vaunted mozzarella in Italy is Mozzarella di Bufala Campana—mozzarella made from the water buffaloes that roam the countryside outside Naples, a cheese with DOP status and international fame. It closely mirrors the earliest iterations of mozzarella, the ones that first surfaced nearly a thousand years ago in the hills of Basilicata and central Campania. Water buffaloes produce milk high in fat, and for many, the cheese made from their milk is the highest expression of the pasta filata discipline—with a concentrated creaminess and a lactic tang that teases your taste receptors and propels you to eat more.

Not all mozzarella can be so brilliant. With the ascendance of pizza into a global icon in the second half of the twentieth century, mozzarella transformed from a regional staple into one of the most consumed cheeses on the planet. Pizza made mozzarella popular, but it also made it mediocre. Somewhere along the way, to keep up with the growing appetite for pizza and the making of pizza in places farther and farther from its birthplace, mozzarella was murdered and reincarnated as an entirely different product—an industrialized cheese meant to travel and built to last. Durable, semiversatile, inoffensive—the Hugh Grant of cheeses. A massive industry has developed, complete with food scientists, marketing execs, and assembly lines, to turn mozzarella into the most amorphous and unobjectionable cheese possible. That product, the one that melts like a dream but tastes like a missed opportunity, has more in common with Velveeta than it does with the mozzarella being made before me.

Forget about the stuff you buy in your supermarket—the cheeselike substance that comes in a single solid block that lasts for months or preshredded in a resealable plastic bag that lives on ominously and indefinitely in the belly of your refrigerator. The Dicecca brothers take personal offense at the existence of such cheeselike substances and the fact that they share the same name as the product they stretch and shape every morning. They might taste good, because even bad cheese tastes good, but it doesn’t taste like this: delicate but robust, intense but ethereal, with a whisper—grass? herbs? pixie dust?—that fades just before you can hear it.

So why such a yawning gap between the mozzarella of southern Italy and that of the rest of the world? If the boys can show up in an African village or on a Kiwi farm and make cheese of remarkable quality, if they can turn pebbly curds into long ivory ropes of mozzarella in the drug-addled din of a Full Moon Party on an island in Thailand, then why is it so damn hard to find great mozzarella outside Italy?

To start with, it’s a physical and technical challenge few can pull off on a daily basis. Periodically during my time in Altamura, I try my hand at mozzarella. Everything that can go wrong does: I fumble the curds, I tear holes through those gorgeous sheets of suspended dairy, I find it’s impossible to duplicate the precise knots that the Dicecca team make so effortlessly. Above all, I scald my hands in the near-boiling water holding the cagliata, even with gloves on. After I let the burns retreat and the confidence return, I try again and again, only to have the cheese remind me just how little I know.

Alfredo Chiarappa

Technical challenges can be overcome with books and YouTube tutorials and apprenticeships, and any argument about the quality of the milk outside Italy the brothers rebuke every time they pack their bags. There’s also a sort of cultural inertia at play here, one wherein the rest of the world, despite the ravenous rate with which it consumes mediocre mozzarella, doesn’t have the motivation and the wherewithal to pull off the good stuff. Sure, you’ll find pockets of excellence here and there, but almost always it’s an Italian, a southern Italian to be precise, making the effort to do it right. In some cases, those little lighthouses of quality were lit by the Dicecca brothers themselves.

10:14 A.M.

One of the last cheeses of the morning production is the one that originally brought me to Puglia: burrata.

More than mozzarella, which is largely associated with Campania, where the bulk of Italy’s mozzarella production takes place, burrata is Puglia’s most renowned creation. Like everything else worth eating in Italy, burrata comes from humble origins. A farming family in Andria, now the burrata capital of Puglia, first started making the cheese in the 1920s as a way to use up yesterday’s mozzarella. It migrated slowly, gaining popularity in the north of Italy only in the 1960s and ’70s. It first started showing up beyond Italy sometime at the dawn of the twenty-first century, when a few enterprising Italian distributors in places such as New York and London established a direct pipeline to Puglia’s cheese world.

For many years, burrata remained elusive, a cheese so rare and fragile that chefs planned their weeks around its arrival. Demand surged as savvy cooks and smart restaurateurs realized that all they had to do was drop a weeping ball of burrata on a plate, dressed with a few tomatoes and a thatch of greenery, and they could charge $20 and still look like geniuses. These days, you can’t drop a fork in a pizzeria in Osaka, a café in Vancouver, or a trattoria in Hanoi without it landing on a mass of burrata.

Throughout the morning, Paolo and Vito take turns doing the job their father first taught them back when they were barely tall enough to reach the cheese: shredding yesterday’s unsold mozzarella by hand to make stracciatella—“little rags.” Mixed with a healthy measure of fresh cream, this forms il cuore, the heart, of burrata, to be deposited directly into a thin outer skin of mozzarella. The entire package is a little miracle, but it’s the oozing, addictive filling that drives the world’s serious eaters so fucking crazy.

Michele grabs a golf ball chunk of curd from the warm bath and uses his palm to work it flat, like a pizzaiolo shaping dough. When the cheese is thin and round, he holds it up by the edges as Paolo deposits a ladle’s worth of the cream-soaked stracciatella directly into the shell, like an edible knapsack. Michele squeezes the edges closed, works it around in his palm, then rips off the excess cheese and seals the package with a pinch and a twist.

Real burrata is a creation of arresting beauty—white and unblemished on the surface, with a swollen belly and a pleated top. The outer skin should be taut and resistant, while the center should give ever so slightly with gentle prodding. Look at the seam on top: As with mozzarella, it should be rough, imperfect, the sign of human hands at work. Cut into the bulge, and the deposit of fresh cream and mozzarella morsels seems to exhale across the plate. The richness of the cream—burrata comes from burro, the Italian word for “butter”—coats the mouth, the morsels of mozzarella detonate one by one like little depth charges, and the entire package pulses with a gentle current of acidity.

The brothers, of course, like to put their own spin on burrata. Sometimes that means mixing cubes of fresh mango into its heart. Or Spanish anchovies. Even caviar. Today, Paolo sends me next door to a vegetable stand to buy wild arugula, which he chops and combines with olives and chunks of tuna and stirs into the liquid heart of the burrata, so that each bite registers in waves: sharp, salty, fishy, creamy. It doesn’t move me the same way the pure stuff does, but if I lived on a daily diet of burrata, as so many Dicecca customers do, I’d probably welcome a little surprise in the package from time to time.

While the Diceccas experiment with what they can put into burrata, the rest of the world rushes to find the next food to put it onto. Don’t believe me? According to Yelp, 1,800 restaurants in New York currently serve burrata. In Barcelona, more than 500 businesses have added it to the menu. Burrata burgers, burrata pizza, burrata mac and cheese. Burrata avocado toasts. Burrata kale salads. It’s the perfect food for the globalized palate: neutral enough to fit into anything, delicious enough to improve everything.

In burrata’s rocket-ship rise to stardom you can trace the anatomy of a global food craze: Find an ingredient either unknown or overlooked by the rest of the world. Build a signature dish around the ingredient that filters well on Instagram. Strip it of all culinary context until it fits comfortably into a million different manifestations. Wait for people to tire of it. Move on to the Next Big Food.

Only the last step remains for burrata. Who knows, maybe the world’s appetite for Puglia’s humble invention will never wane. In the meantime, the big question is: Where the hell is all this cheese coming from? Sure, a handful of larger, ambitious producers in Puglia export burrata (pro tip: most goes out on Monday, so get yours at the top of the week), but demand outstripped supply long ago. Chances are, if you’re slicing into a ball of creamy cheese in a posh café in Mexico City or an Italian restaurant in Copenhagen, it may be perfectly delicious, but it ain’t burrata from Puglia.

No country in the world faces more threat of counterfeit food than Italy. The value of Brand Italy, and the country’s cornucopia of world-class artisanal products, makes it vulnerable to imitators both inside the country and out. Years ago, the ’Ndrangheta, the Calabrian mafia, infiltrated the world of high-end olive oil and has been selling tens of millions of dollars’ worth of fraudulent bottles to global buyers (mostly Americans) ever since. In Emilia-Romagna, home to some of Italy’s most famous ingredients, task forces have been established to root out counterfeit Parmesan, prosciutto, and balsamic vinegar. So widespread is the epidemic that a new class of food detectives, trained to identify fakes, has emerged over the past decade.

In the face of global demand, the cheese makers of Andria have taken a cue from their counterparts in the north and formed a coalition aimed to protect their coveted creation. Along with help from the Puglian government, they have codified everything from working conditions to chemical makeup to the proper shape and size of true burrata. They also secured the coveted Indicazione Geografica Protetta (IGP) status for the cheese, which means that complying producers can add a special label to their cheese. But no rules or regulations can compete with the ferocious appetite of a fickle food world and the forces ready to capitalize on Brand Italy. If someone, whether a hardened criminal or just a savvy marketer, wants to take advantage of burrata’s good name, he’ll find a way.

Up until this point, I had been dreaming of returning to Barcelona with a suitcase swollen with burrata, but Vito looks reticent. Rarely does Dicecca burrata travel outside Altamura, let alone the Italian peninsula. “Real burrata needs to be eaten the same day, two days at the most. It begins to die slowly the second after it’s made.”

10:47 A.M.

The front of the shop has its first line of the day as the streets of Altamura buzz with midmorning traffic. Vittoria and Maristella deftly handle the waves of customers, doling out hunks of scamorza, packages of burrata, the occasional wedge of blue or round of goat cheese.

“Angelo! Caciocavallo! We need it now!”

In the back, the brothers make the last push of the morning. Michele and Paolo initiate the daily deep clean—hot water coursing through the battery of stainless steel—while Angelo ferries cheese to the front of the store. Vito works the last vat of milk while thumbing through his Facebook feed. Ricotta, literally “recooked” in Italian, is always the last fresh cheese produced, a final surge of heat used to get just a little bit more out of the day’s milk supply. He uses a six-foot metal whisk to stir and cut through the hot mixture, separating the liquid from the curds that settle below the surface. Later, he works through a stack of plastic baskets, filling each with a generous deposit of the soft curds that he fishes out of the murky depths with a giant slotted ladle.

Experiments are generally left toward the end of the morning, when the rest of production is winding down. With the ricotta lined up in baskets on the countertop, the last of the watery whey draining through holes of the basket containers, Vito goes through the cheese lockers tucked in the corner and begins to pull out and test a few of his ongoing projects.

In between his trips up front, Angelo rolls wheels of fresh goat cheese in a bed of dried herbs—centodieci erbe, 110 herbs. “I was on my mountain bike riding through the natural park, smelling the wild arugula, the herbs. I said, ‘Fuck, why don’t I do a cheese with the herbs?’” If herb-crusted goat cheese doesn’t sound radical to you, keep in mind this is Italy, where neither fresh goat cheese nor adding 110 herbs to simple fare is standard practice. “Everyone at first was like ‘Why would you ruin the cheese with herbs?’” An eighty-year-old man, a friend of Angelo’s who lives in the park, collects herbs for him in exchange for free cheese.

The modern food world is flush with technical and cross-cultural experimentation. Usually it comes from the younger generations, who want to unleash the soaring guitar solos without first learning the chords. All over the world, you’ll meet chefs who can turn hazelnut oil into tiny, edible spheres and parsley stems into bubbling, ethereal foams but can’t cook a steak or scramble an egg.

By those measures, the boundary pushing pursued by the Diceccas is relatively tame. More important, it comes after fifteen years of learning and refining the core techniques of pasta-filata. There’s a reason why every day starts with the fundamentals: a battery of cheeses made with nothing more than milk, water, and four generations of repetition. Simple, unadulterated mozzarella and burrata will always be the engine that drives Puglia’s cheese culture, and the Diceccas will never abandon tradition. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t time and space to innovate.

“Our dad thought we were crazy, and continued to think that until the cheese sold,” says Angelo. “In the last ten years, I’ve sacrificed ten kilos of cheese a day giving out samples, educating our customers. These aren’t cheeses they’ve seen before.”

Remember: This is the town that beat McDonald’s, that chose ciabatta over cheeseburgers, focaccia over French fries. Matters of the stomach are not taken lightly here. Food isn’t calories; it’s history, heritage, life. To budge an inch means to give up a foot. To make a compromise is to stop believing. Most of the world doesn’t have this ethos simmering beneath the surface, ready to boil over whenever threatened, which may hinder advancement but keeps the bread and the cheese tasting as they always have.

But it also means that the Diceccas’ innovations in the caseificio are up against a tough audience—one that doesn’t take well to mango in the burrata and cranberries on the blue cheese. Yet they continue to push forward in the quest for new flavors. Maybe it’s the outsiders buying up their funky cheeses? you ask. There are no outsiders—the cheese doesn’t travel well, nor do they want it to travel when it doesn’t need to. Ninety-five percent of the Diceccas’ sales come directly from the storefront.

Vito brings an armful up to the front, where the scene teeters on the edge of chaos. Angelo cuts a caciocavallo the size of a watermelon with a long cheese knife while Maristella yells at him from the other side of the counter. “That’s not how you cut caciocavallo!”

A man rolls by in a BMW and honks his horn from the street corner. Angelo grabs a plate of cheese scraps and offers him a taste through the window. “He’ll be back to buy more later,” he says with a satisfied smile.

An older woman steps up to the counter and Vittoria passes a small bag over without more than a “Ciao” exchanged between the two of them. “A domani!” she says before shuffling out. See you tomorrow.

Vittoria fills a portable cooler with a full selection of Dicecca formaggio: a few balls of burrata, a massive braid of mozzarella, a round of chili-covered goat cheese. A businessman from Altamura, now living in Poland, oversees the construction of the care package, his face jostling between grin and grimace. “It’s been hard to adjust to eating outside of Altamura,” he says. “I miss it all, especially the cheese. This is always my last stop on the way to the airport.”

A nonna in a black dress and shawl is staring at the cheeses in the side cooler, home to the Diceccas’ most aggressive experiments. She looks perplexed. Vito spots her and comes from behind the counter to assist.

“Buongiorno, Anna! Come stai?”

“Bene, bene.”

“Would you like to try something today?”

“Why not? What is this, pistachio?”

“No. That’s matcha.”

“What’s matcha?”

She takes a taste of the tea-spiked goat yogurt; her eyes open wide at first, then drift to the corner of the room, avoiding direct contact with any of us looking on. “Very interesting.”

In the end, she buys two balls of burrata and a scoop of nodini and moves on.

9:47 P.M.

“Vaffanculo! Che cazzo! Pezzo de merda!”

The five Dicecca siblings are gathered around the television at their parents’ house, watching the European Cup quarterfinal between Italy and Germany. After two scoreless extra periods, the game comes down to a final shoot-out, and nobody is happy with the way things are going. When Darmian misses the second penalty kick in a row for Italy, a chorus of curse words rains down on the television screen.

On the table are the fruits of the caseificio cornucopia: balls of mozzarella, one-bite nodini, wedges of scamorza, and a single swollen sphere of burrata, waiting to be breached. Plus pane di Altamura. That’s it: bread and cheese. What we ate for breakfast and for lunch. If you think working in a caseificio all day, every day, might curb your appetite for cheese in the off hours, you’d be wrong. Vito, Angelo, and Paolo eat each cheese as if it might be their last.

“I don’t eat a lot of meat or fish,” says Vito. “I mostly just eat cheese.” On cue, Paolo scoots by and air-drops a few nodini directly into his mouth.

The match ends in victory for the Germans, and a collective groan echoes across the country. Mom comes in. She’s been at the hospital, caring for her husband, who’s recovering slowly from his accident. It’s clear that his days at the caseificio are behind him. She makes her way around the room, kissing her children one by one. She turns to me. “Have you eaten?”

With the match over, they return to the table one by one. Angelo grabs a slice of Altamura bread and caps it with half a ball of mozzarella. Vito works a fork through the soft folds of a burrata. Paolo pops nodini into his mouth like popcorn kernels.

Their relationship as brothers takes on the same rhythms as their relationship as partners in the store: a near-wordless synchronicity, wherein they orbit constantly around one another but rarely come into direct contact. There are moments of subtle tenderness—a midmorning espresso delivery by Angelo, a cigarette shared during a quick break from production—but for the most part, they go about their business and their lives in silent symbiosis.

Each speaks almost exclusively in the first person—“my trip,” “my cheese,” “my experiment.” At first it’s disarming, as if the small space of the caseificio hasn’t left enough room for “we,” but the more time I spend with the brothers, the more I realize that it’s a way of maintaining a footprint of independence in a world where everything—jobs, meals, cigarettes—is shared.

Alfredo Chiarappa

“That’s the beauty of it,” says Vito. “I can leave tomorrow, and I know my family will be just fine. Same goes for Paolo or Angelo.” Fine for a time, sure. Paolo will take up the ricotta duties, Angelo will watch over Don Vito and the formaggio clandestino and whatever experiment his brother has brewing. They’ll all share cheeses through a constant stream of messages and find a way to get by, but something will be missing.

“I have so many places I want to go,” says Vito. “My brothers, too.” He rattles off a list of the latest outposts in need of mozzarella aid: a trattoria in Hong Kong; a farm outside Vancouver; an island waiting to be discovered, where the milk is dense and aromatic and the moon never sets.

“It would be beautiful if we could travel together,” says Paolo. “But we need to be careful. Maybe the day we all leave together is the day we never come back.”