Sewed up his heart!” shouted the headline. Readers of a Chicago newspaper gasped at the exciting news, and why not? In 1893, this was a medical miracle made even more newsworthy because it had been performed by one of North America’s few black surgeons.

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams was the remarkable surgeon who was clearly committed to defying the status quo of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century medicine.

What is significant for Canadians to know is that this man had an ancestral link to the Maritimes. Helen Buckler, in her excellent biography, Daniel Hale Williams: Negro Surgeon, traced his heritage, on his mother’s side of the family, back to a freed slave who lived in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, in the late 1700s.

Born in 1856 to Pennsylvania parents of mixed Shawnee Indian, Welsh, Irish, Scottish and African-American blood, Dan was fair-skinned with red hair. Like his parents and grandparents, he took great pride in the knowledge that he could claim African roots. During his lifetime, despite his fair skin, he refused to pass himself off as a white man. This strength of character is not surprising, since, in order to reach his goal of excelling in the medical profession, he was forced to deal with enormous obstacles.

He was only eleven when his father died, and his mother arranged for him to become a shoemaker’s apprentice. He hated the tedious work and courageously ran away, making his way back home only to discover that his widowed mother had moved, leaving him to fend for himself.

Dan, however, was not your average youngster. By the age of seventeen, he owned a small barbershop in a town in Wisconsin. Not content with this role, he joined an established business in a nearby community. Barbering part time, playing the bass fiddle in the evening, Dan was able to earn enough money to pay for private tutoring. After completing high school, he began to read law books, but concluded the legal profession was not for him, especially as he abhorred confrontation.

Several articles in the community’s small weekly newspaper caught Dan’s attention. They chronicled the interesting adventures of the town’s doctor and former mayor, Dr. Henry Palmer. The stories intrigued Dan, and in 1878 he convinced Dr. Palmer to accept him as an apprentice. The next two years proved to be anything but adventurous for the young apprentice. He had to balance mundane duties such as sweeping the doctor’s waiting room and cleaning his horse barn with the responsibility of helping to dress wounds, set fractures and test urine samples.

Dan was ecstatic when in 1880 his mentor informed him that he would be prepared to give him the credentials needed for medical school. Elated by this prospect, Dan chose the Chicago Medical College, which was later affiliated with Northwestern University. The young man’s first year at medical school proved to be another difficult time in his life. He was barely able to exist on borrowed money, and although he studied constantly, his grades were mediocre. Fortunately, his second year was more rewarding. He found anatomy classes fascinating and was able to visit Mercy Hospital, where he witnessed the impact that Joseph Lister’s evolutionary theories on antisepsis were having on surgery.

In March 1883, Daniel Hale Williams was qualified to write MD after his name. Now twenty-seven and equipped with an Illinois medical licence, he opened his office in an area of Chicago that would offer him access to both white and black patients. Dr. Williams soon found himself performing surgery on a regular basis; he was asked to demonstrate his surgical ability to medical students, and his name often appeared in The Conservator, a Negro newspaper.

The outstanding surgeon’s reputation quickly spread, and he was invited to join the prestigious Hamilton Club, a Republican organization with few black members. He was also appointed to the Illinois State Board of Health, though he was never fully recognized there.

In 1890, a plea for help from a pastor at a local black church served as a cruel reminder of the rampant racism of the day. The Reverend Louis Reynolds was angry that his well-educated sister Emma could not find a

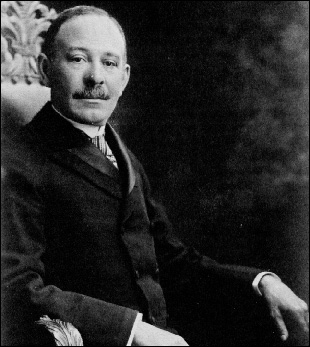

Daniel Hale Williams, chief surgeon at the Freedmen’s Hospital, Washington, DC, 1894-1898. DANIEL HALE WILLIAMS: NEGRO SURGEON

nursing school that would accept her as a student. Dr. Williams — greatly disturbed by this situation — decided it was time to found a hospital where black doctors could serve as interns and where black women could train as nurses. He insisted on only one thing: it must be an interracial institution that would be open to all, regardless of race, gender or creed. In May 1891, Provident Hospital opened its doors with black and white doctors on staff, and seven young women, including Emma Reynolds, enrolled in the first interracial nursing class in the United States. (A Canadian woman, Jessie Sleet, was a member of that class. She became the first black woman to work as a district nurse for a charitable organization in New York City.)

It was at the new hospital, two years later, that Dr. Williams performed his miraculous surgery. James Cornish was in critical condition when he was rushed to Provident Hospital. He had been stabbed in the chest, was in severe pain and obviously dying. Most colleagues, when faced with such a terrible injury, would not have considered operating. Dr. Williams did not share this kind of reticence. Boldly and skillfully, he repaired the tear in his patient’s heart. Today, the significance of this surgery continues to be challenged, but there is little doubt that Dan Williams deserves full credit for performing the first operation of its kind in medical history.

James Cornish made a rapid recovery. The positive outcome encouraged Dr. Williams to perform at least two other successful heart operations. Later, while working at the Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., he operated on a number of other complex cases. During his time there, fewer than ten postoperative deaths were reported, yet he was never invited to join the District Medical Society, which was a predominantly white professional association. Dr. Williams felt it was imperative that he respond to this racial prejudice. In 1895, with the support of three white and five black physicians, the Medico-Surgical Society of the District of Columbia was formed. The same year, he helped found the National Medical Foundation.

Engrossed in his surgical practice, Williams was shocked to learn that his status at Freedmen’s Hospital was being undermined. When the situation became unbearable, he concluded he had no choice but to resign from the hospital and return to his practice in Chicago.

Within months of his return to Chicago, Dr. Williams turned his attention to the South, where he knew the black population desperately needed access to proper medical care. For some time, a medical college in the southern United States had been trying to create an academic environment that would lead to the graduation of a greater number of black doctors. Dr Williams was more than willing to help them achieve this objective. Without remuneration, he began to work and teach at the college. His enormous commitment to improve medical care for blacks living in the American South had a significant payoff: it fostered forty hospitals in twenty different states. Helen Buckler insists that his fervour, his unremitting labour and uncompromising perfectionism truly earned him the right to be known as the “Moses to Negro Medicine.”

In 1912, Dr. Williams reluctantly resigned from Provident, the hospital that he had helped found. The man who had replaced him as its medical director had always resented the older physician’s high standing in mainstream medicine and had done everything possible to destroy his credibility. However, Dr. Williams’ reputation remained unblemished. In 1913, he was the only black man among a hundred surgeons who were formally installed as members of the newly formed American College of Surgeons, and in 1919, black doctors practicing in Missouri presented him with a silver cup to express their appreciation for his work in advancing the medical profession in that state and all of the United States.

On August 4, 1931, Daniel Hale Williams died. In his will, the bulk of his estate was designated for the benefit of his race. The largest bequest, $8,000, went to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Sadly, the hospital Dr. Williams founded had a troubled existence, even though a new faculty with three hundred beds was opened in 1983. However, this rejuvenation was brief. Five years later, serious financial and management problems resulted in the sudden closure of Provident Hospital. In 1991, the then-derelict facility was purchased by the city, and more than fifty-eight million dollars was spent on renovations. Calls to Provident Hospital in Cook County revealed that there is little evidence at the refurbished facility to mark Dr. Williams’s contribution to the original hospital, and there is no official acknowledgment of his remarkable medical career. No play or movie has been made about this extraordinary doctor and surgical pioneer; Helen Buckler’s book stands alone.

This raises a question: If Dr. Williams had been white, or if he had chosen to keep his black heritage a secret, would his memory have received the tribute it deserves?

Dorothy Grant