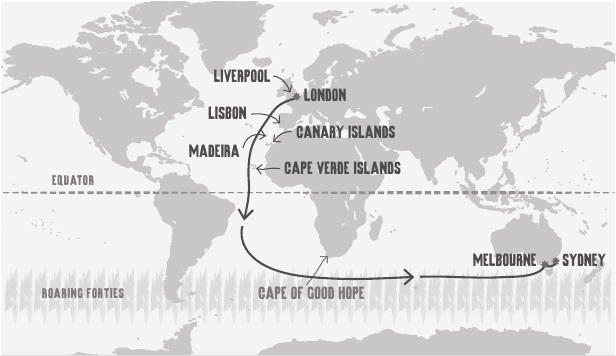

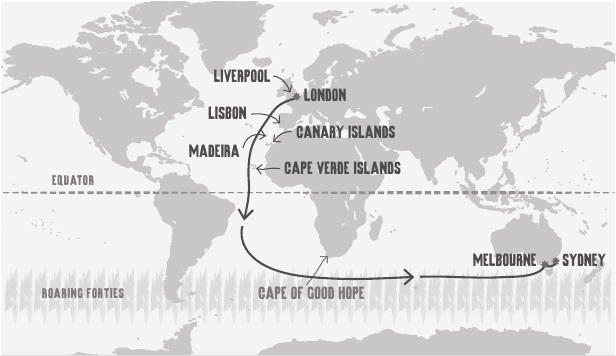

The vast majority of gold-rush immigrants were travelling from British ports. For them, the early part of the journey proceeded in a southwesterly direction down the east Atlantic Ocean. The ship’s route would descend past the Bay of Biscay, Lisbon, Madeira, the Canary Islands and the lumpy knob of West Africa, through the Tropic of Cancer towards the equator. Sometimes, if conditions were poor and ships made slow progress, the English coastline could still be visible for weeks. But eventually, all familiar markers disappeared from sight.

The journey from Britain to Melbourne

Now there was only the vast rolling ocean.

Just six days after her departure, English schoolgirl Jane Swan noted it was getting perceptibly warmer but, she complained to her diary, we get quite tired of having nothing to look at but the sea. Passengers with more serious grievances were also quick to make them known. After all, most of the gold-rush immigrants had paid for their passage, or at least they were there of their own free will—not as convicts or naval conscripts.

On the Lady Flora, J. J. Bond said, the ’tween deck people think they are living too much like pigs. These disgruntled passengers petitioned the captain to land at the nearest port so they could acquaint the owners of the ship with the condition of facilities that were unequal to her crowded state.

The passengers’ objection to living like swine was fair enough. They would all have heard of the Ticonderoga, the famous ‘plague ship’ that arrived at Port Phillip in November 1852 after a hell voyage in which one hundred of its 795 assisted migrants died—over half of them children. A report by the Immigration Board in Melbourne later stated that the ship:

did not appear to have been cleaned for weeks, the stench was overpowering, the lockers so thoughtlessly provided for the Immigrants’ use were full of dirt, mouldy bread, and suet full of maggots, beneath the bottom boards of nearly every berth upon the lower deck were discovered…receptacles full of putrid ordure, and porter bottles etc, filled with stale urine, while maggots were seen crawling underneath the berths.

Jane Swan’s family, on board the William and Jane, also signed a petition. This one was about a bad water supply, and it worked. They were supplied with good water from the tanks.

Petitioning was something the English emigrants would have been quite familiar with. It was part of a longstanding tradition in which people got together to complain about and combat local grievances. The journey to Australia, being long and crowded, made getting together to complain quite straightforward. Since nobody liked the idea of hostile crowds in confined spaces, most ship captains were at least willing to hear petitions and delegations without taking offence.

By the time most gold seekers arrived on dry land, they had already made friendships and alliances: strong bonds based on shared space and sometimes common grievances. Many passengers referred to shipboard life as being like one well regulated family. The Marco Polo Chronicle put this clannish feeling down to the depression that associates with ‘goodbye’ followed by the vast amount of physical suffering to be surmounted through seasickness. Our floating world, they called it.

This intense bonding, coupled with the sense of having endured an ordeal together, would later make an important contribution to solidarity on the goldfields.