The most common type of question in the reading portion of the Praxis exam is what’s called a short-passage question. You’re given a selection of text, usually only three or four sentences in length, and you’re asked one question about it. The question is unique to the passage, and the passage is unique to the question.

In the following sections, we outline the types of information the questions focus on and give you pointers on how to figure out what the correct answer is.

Ferreting out the main idea

The most common — and the most straightforward — type of short-passage question is a “main idea” question. The wording of the question is usually along the lines of “The main idea of the passage is …” or “The primary purpose of the passage is …”, and your mission is to select the answer choice that best completes the sentence. Basically, phrases like “main idea” and “primary purpose” are just fancier ways of asking

- “What’s this about?”

- “What’s the point of this?”

- “What is this paragraph trying to say?”

Although such questions may seem easy after you’ve had a bit of practice with them, they can be difficult in the sense of being deceptively simple if you’re not used to them. Questions like these can be challenging because the wrong answers appear flashier or more attractive than the right one. They may have more details in them, or they may contain more exact words from the passage.

However, you’re not looking for the statement about the passage that is the most detailed or the most specific — you’re looking for the statement that is true. And there will be only one of those. The other four choices, for one reason or another, will be wrong. A common tactic the test-writers use on such questions is to make the right answer so vague or uninteresting that you barely notice it. The wrong answers stand out more. But never forget that all you’re trying to do is pick the statement about the purpose of the passage that’s true (in other words, not wrong) — no more and no less. Consider the following example.

However, you’re not looking for the statement about the passage that is the most detailed or the most specific — you’re looking for the statement that is true. And there will be only one of those. The other four choices, for one reason or another, will be wrong. A common tactic the test-writers use on such questions is to make the right answer so vague or uninteresting that you barely notice it. The wrong answers stand out more. But never forget that all you’re trying to do is pick the statement about the purpose of the passage that’s true (in other words, not wrong) — no more and no less. Consider the following example.

Anyone who paid attention in grade-school science class could tell you that the five classes of vertebrates are mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and fish. For centuries, these categories made sense to scientists because they represented clear distinctions based on what we were able to observe about the animal kingdom. But now that we know more about evolutionary history, the borders between these traditional and visually “obvious” classes are not so clear. A crocodile looks more like a turtle than a penguin, but the common ancestor of the crocodile and the penguin actually lived more recently than did the common ancestor of the crocodile and the turtle.

Anyone who paid attention in grade-school science class could tell you that the five classes of vertebrates are mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and fish. For centuries, these categories made sense to scientists because they represented clear distinctions based on what we were able to observe about the animal kingdom. But now that we know more about evolutionary history, the borders between these traditional and visually “obvious” classes are not so clear. A crocodile looks more like a turtle than a penguin, but the common ancestor of the crocodile and the penguin actually lived more recently than did the common ancestor of the crocodile and the turtle.

The primary purpose of the passage is to

(A) explain how penguins evolved from crocodiles.

(B) dispute some recent theories in the field of evolutionary biology.

(C) correct a misconception common in grade-school science curricula.

(D) discuss how a biological concept is more complicated than it looks.

(E) summarize a disagreement about vertebrates between two schools of zoologists.

The correct answer is Choice (D). To understand why Choice (D) is correct, consider: Does the passage “discuss how a biological concept is more complicated than it looks?” Yes, it does. In fact, it indisputably does — in other words, there is no reasonable way to argue that the passage does not do this. So (D) is the right answer because it cannot possibly be wrong.

As for the others, by now you’ve figured out that they’re all wrong. But look at what they have in common: All the wrong answers stand out by repeating specifics or key words from the passage — but they also twist those specifics so the statements are no longer true.

Choice (A) is wrong because the passage technically doesn’t say that penguins evolved from crocodiles; it says that penguins and crocodiles have a common ancestor. And even if the passage did say this, it wouldn’t be the primary purpose of the passage, because it’s only one example given right at the end. The test-writers know that the example given at the end will be fresh in your mind, so they try to get you to jump the gun by making it the first choice!

Choice (B) is wrong because of the verb it uses. The author is indeed talking about “recent theories in the field of evolutionary biology,” but he isn’t disputing them, only explaining them (there is no indication that the author disagrees). Always remember that it only takes one false move to make an answer choice wrong!

Choice (C) is wrong because the passage technically never says that the vertebrate classes as explained in schools are incorrect (a “misconception”). The five classes of vertebrates are still mammals, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and fish. The passage discusses some interesting information that seems as if it might lead to scientists changing those categories somehow in the future, but it never says they’ve done so already!

As for Choice (E), did the passage say or imply anything about “two schools” of zoologists? No. The passage explains that zoologists (biologists that specifically study animals) nowadays have more information than zoologists did in the past, but it never hints at anything about a debate.

Discerning the author’s tone and intent

The most common type of reading-comprehension question that students complain about — even dread — is the authorial-intent question. “I can answer questions about the information in the passage,” they say, “but how am I supposed to know what the author intended to do? What am I, a mind reader?” But you don’t have to be a mind reader to answer this type of question. You answer it the same way you answer any other question on the Praxis reading test — four of the choices are wrong, and you pick the one that isn’t.

Look at it this way: If I showed you a picture of a man carrying a guitar, and I asked you what he was on his way to do, you wouldn’t know. He might be on his way to band practice, he might be returning the guitar to a friend, or he might be an actor who’s portraying a musician in a play. All of those answers are plausible. However, if it were a selected-response question, all you’d have to do is eliminate the four implausible choices and select the one that remains. If the man were on his way to build a porch, he would have a toolbox rather than a guitar; if he were on his way to help put out a fire, he’d have a bucket of water instead of a guitar; and so forth.

That’s how you answer an authorial-intent question without needing to be psychic. Four of the choices are implausible, and the right answer is the one that’s left!

The frequent complaint by horror-movie fans that their favorite genre is discriminated against at the Academy Awards is difficult to assess. The data would seem to back it up: After all, in the 85-year history of cinema’s top prizes, only one horror film — 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs — has taken home the Oscar for Best Picture. On the other hand, many critically respected scary movies have simply had very bad luck: Jaws and The Exorcist almost certainly would have won had they not been up against Oscar-magnets One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The Sting in their respective years. Some critics have suggested that the “horror movies never win awards” objection is a self-fulfilling prophecy: When a movie wins many prestigious awards, we stop thinking of it as a “horror movie,” no matter how scary it is.

The frequent complaint by horror-movie fans that their favorite genre is discriminated against at the Academy Awards is difficult to assess. The data would seem to back it up: After all, in the 85-year history of cinema’s top prizes, only one horror film — 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs — has taken home the Oscar for Best Picture. On the other hand, many critically respected scary movies have simply had very bad luck: Jaws and The Exorcist almost certainly would have won had they not been up against Oscar-magnets One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The Sting in their respective years. Some critics have suggested that the “horror movies never win awards” objection is a self-fulfilling prophecy: When a movie wins many prestigious awards, we stop thinking of it as a “horror movie,” no matter how scary it is.

In the preceding passage, the author’s intent is to

(A) analyze the idea that horror movies are discriminated against at the Oscars.

(B) rebut the assertion that horror movies seldom win prestigious awards.

(C) persuade Academy Awards voters to stop overlooking deserving horror films.

(D) satirize a silly idea about “discrimination” against a certain genre of films.

(E) predict whether more horror movies will win Oscars in the near future.

The correct answer is Choice (A). Why? Because there’s no way that the correct answer can’t be Choice A. The passage is about the idea that horror movies seldom win Oscars, and the author is indisputably analyzing that idea. Remember, “analyze” is just a fancy word for “look at closely and thoroughly.” Because this is all that Choice (A) asserts to be the case, there’s no room for it to be wrong.

Choice (B) is wrong because the author is not rebutting anything (to “rebut” means to “offer a counterargument”). Choice (C) is wrong because the author isn’t trying to persuade anyone to do anything, only presenting information. Choice (D) is wrong because the author isn’t satirizing anything (“satirizing” means “making fun of” — did you laugh?). Choice (E) is wrong because the author doesn’t say one single word about what may or may not happen in the future, so the passage doesn’t contain any predictions.

If you have a knack for this sort of thing, you may have noticed that the initial verb in each answer choice was pretty much all you needed to eliminate the four wrong answers: The author is not rebutting, persuading, satirizing, or predicting, but he is analyzing (because hey, how could he not be analyzing?). And even if you didn’t pick up on that, don’t despair, because you’ve picked up on it now.

We certainly don’t mean to imply that you should only look at portions of the answer choices. A cardinal rule of selected-response test-taking is that you should always read all the choices in their entirety before making a decision. What we’re saying is that sometimes the distinction between the right answer and the wrong ones doesn’t depend equally on every single word the answers contain. It only takes one wrong word to make an answer choice wrong, so because Choices (B), (C), (D), and (E) are all wrong based on their first words, those first words are all you need to eliminate them, leaving only Choice (A), which must, therefore, be right.

As for questions about the author’s tone, those are basically the same game. The only difference is that you deal with adjectives instead of verbs. For example, whereas the answer choices for an authorial-intent question may begin with the words analyze, rebut, persuade, satirize, and predict, the answer choices for a question about the author’s tone may describe that tone alternately as analytical, argumentative, persuasive, satirical, or speculative. In either case, you should approach the question in the same way: Eliminate four wrong answers and pick the one that’s left.

Looking at Long-Passage Questions

Though the Praxis reading test has many short-passage questions that pair very brief paragraphs with generally broad questions in a 1:1 ratio (that is, one question per passage), some of the test features long-passage questions, wherein several questions are asked about a single passage of two or three paragraphs in length.

Though there are no hard-and-fast rules about which types of questions can or will be asked about which types of passages (in other words, a main-point or vocabulary-in-context question could be asked in reference to a long passage), certain types of questions are more commonly paired with the long passages. A question dealing with support for an argument, for example, is more likely to pop up in reference to a long passage, simply because the short passages are usually too brief to contain much in the way of detailed support for (or attacks on) an argument.

So, although there’s no reason why a long passage couldn’t contain any of the types of questions discussed in the “Mastering Short-Passage Questions” section, long passages are far more likely than short passages to contain the types of questions discussed in the following sections.

Purpose and paraphrase

If there’s one thing you can expect from a series of long-passage questions, it’s that there’ll be at least one question that identifies a little detail or factoid from somewhere in the passage and asks you “What’s the point of this?” The question won’t be phrased that way, of course. It will be more drawn out, along the lines of one of the following:

- When the author writes that “this, that, or the other,” he most nearly means that… .

- It can be inferred that the author views the “such-and-such” as a type of… .

- It is implied that the “blah blah blah” is significant because… .

Although a “What’s the point of this part?” question can be phrased in any number of ways, it always basically comes down to the same thing: The question quotes a portion of the passage (it may be an entire sentence or a small detail comprised of two or three words), and it essentially asks, “Why did the author mention this right here?”

This question type may sound similar to authorial intent and mind reading (see the section “Discerning the author’s tone and intent” for more about that), but it’s not. Just as with authorial-intent questions, the best method of answering a “What’s the point of this part?” question is to eliminate wrong answers until only one choice is left.

In theory, an author may use a particular phrase or reference a particular detail for any number of reasons — just as a piece of writing may be about any topic under the sun or written with any of a host of intentions. In practice, however, Praxis reading questions tend to ask about only a finite number of points that a particular phrase may have. With reference to the types of questions referred to in the preceding bullet points, for example, the most likely explanations are as follows:

- If a question asks you “what the author most nearly means by” a particular phrase, you’re simply being asked for a paraphrase of the quoted text. A good strategy is to rephrase the quotation to yourself in your own words before looking at the choices, and then pick the answer choice that is the closest to what you just said.

- If a question asks you to “infer how the author views” the quoted detail, the quoted detail is probably a particular example of some general category that is referenced elsewhere in the passage (for example, if the passage as a whole is about mythical animals and the author mentions Bigfoot, he does so because Bigfoot is a type of mythical animal).

- If the question asks “Why is this significant?” about a quoted detail, the point of the detail is likely that it impacts the meaning of something else. Perhaps it’s an important example of some general principle that the passage is trying to prove or explain, or perhaps it’s a notable exception to that principle.

Arguments and support

A typical argumentation/support question on the Praxis reading test quotes a statement from the passage back to you — usually a detail or factoid — and then asks you why the author made mention of that detail or factoid at that particular juncture. Usually, the detail in question is being used to support a particular assertion, and you’re being asked what assertion or viewpoint it’s being used to support.

The best analogy here is to the vocabulary-in-context questions (see the earlier section, “Putting vocabulary in context”). Why? Because there’s no point in trying to answer the question without looking back at the passage. Just as the word in a Praxis vocabulary question is meaningless out of context, the detail in a Praxis argument/support question is meaningless out of context, too.

Just as you should answer the vocabulary questions by plugging the five answer choices back into the passage to see which suggested word works as a synonym, you should approach the argumentation/support questions by plugging the five answer choices into the passage to see which suggested concept relates to the context surrounding it.

Just as you should answer the vocabulary questions by plugging the five answer choices back into the passage to see which suggested word works as a synonym, you should approach the argumentation/support questions by plugging the five answer choices into the passage to see which suggested concept relates to the context surrounding it.

After all, even though a piece of argumentative writing can be about anything, it’s still going to be arranged in a logical fashion. You wouldn’t offer a detail to support one idea when you’re right in the middle of talking about something else!

Getting the hang of “If” questions

“If” questions (so called because they usually begin with “If it were found that …”) are like argumentation/support questions, only instead of asking how a detail from the passage is used to support the author’s argument, they ask how a detail or fact that is not in the passage would affect the author’s argument if it were found to be true. The point of such questions is that they demonstrate advanced logical thinking — that is, they show that the test-taker fully understands the weight and implications of the argument being made on an abstract level, rather than merely showing that the test-taker comprehends the passage’s exact words.

For example, consider a question like “If it were found that the defendant in a murder trial has a twin brother, how badly would this weaken the prosecution’s case?” The answer would be that the prosecution’s case would be weakened if it relied solely on eyewitness testimony but that it would not be weakened if they had fingerprint evidence, because twins look alike but don’t have identical fingerprints. Don’t worry — questions on the test don’t involve outside knowledge; they deal only with the information provided to you in the passage and the questions themselves. (So if, in the example given here, they wanted you to base your answer on the fact that twins don’t have identical fingerprints, the passage would tell you this.) This is just an example of what is meant by an “if” question.

If you’re good at logical reasoning, you may be excited about answering “if” questions. But if you’re not so hot at logical reasoning, rest assured that there are simple, step-by-step ways to eliminate wrong answers to an “if” question, just as there are for the other types of questions.

“If” questions come in two basic types. In the first kind, the question gives you a detail, and the answer choices are possible ways that the detail may affect the argument. Keep in mind that there are only three ways in which a given detail can possibly affect an argument:

- It can support it.

- It can undermine it.

- It can have no effect.

However, the question needs to have five choices, so the choices can involve questions of degree: “The given fact completely proves the argument,” “The given fact supports the argument slightly,” “The given fact completely disproves the argument,” “The given fact undermines the argument slightly,” and “The given fact has no effect on the argument.”

“If” questions also often pop up in reference to passages that compare excerpts from two authors, in which case the answer choices may be something like “The given fact supports the author of Passage 1,” “The given fact undermines the author of Passage 1,” “The given fact supports the author of Passage 2,” “The given fact undermines the author of Passage 2,” and “The given fact has no effect on the argument of either author.”

The second type of “if” question reverses this dynamic. Instead of providing you with a single detail and giving you five choices about how the detail affects the argument, this type of “if” question asks you to identify which of five possible details supports or undermines the argument.

The way to approach such a reverse if question is to begin by understanding that a detail has to be about the same thing as the argument in order to have any effect on it one way or the other. So, your first step is to eliminate all the choices that are unrelated (for example, if the author’s argument is that Babe Ruth is the greatest baseball player of all time, then a factoid about basketball’s Michael Jordan or football’s Jerry Rice neither supports nor undermines it). After you’ve eliminated the answer choices that have no effect one way or the other (unless you’re being asked to identify the detail that has no effect on the argument, which is rare, but possible), the next step is to look for points that are either consistent with or mutually exclusive to the author’s viewpoint. A detail or factoid that is consistent with the author’s viewpoint (a detail that would or could be true if the author is right) supports that argument, and a detail or factoid that is mutually exclusive to (that is, couldn’t be true at the same time as) the author’s viewpoint undermines it.

Sample questions for long passages

In this section, you get a chance to practice some “purpose” questions, “support” questions, and “if” questions by looking at a long passage followed by an example of each.

“Did King Arthur really exist?” may seem like a fairly straightforward question, but the only possible answer to it is “It depends on what you mean by ‘King Arthur.’” Though virtually all adults now understand that the existence of a historical English king by the name of Arthur wouldn’t involve his possessing a magical sword called Excalibur or being friends with a wizard named Merlin, far fewer people realize how tricky it would be to call him a king, or even to call him English.

“Did King Arthur really exist?” may seem like a fairly straightforward question, but the only possible answer to it is “It depends on what you mean by ‘King Arthur.’” Though virtually all adults now understand that the existence of a historical English king by the name of Arthur wouldn’t involve his possessing a magical sword called Excalibur or being friends with a wizard named Merlin, far fewer people realize how tricky it would be to call him a king, or even to call him English.

Every first-millennium history book that makes mention of Arthur indicates that he lived during the late 5th and early 6th centuries and agrees that he played a role in the Battle of Badon in approximately 517. We know that the Battle of Badon was a real event, but what a historical Arthur might have done besides participate in this battle is anyone’s guess. The earliest source that mentions Arthur, the Historia Brittonum of 828, links him with Badon but refers to him only as a dux bellorum, or war commander — not as a king (the fact that no British historical text composed between 517 and 828 mentions Arthur, even though they all mention Badon, is not terribly convenient for those who wish to believe in his existence).

Indeed, there wouldn’t even have been a “king” in that place at that time. The Roman Empire had only recently pulled out of Great Britain, and the power vacuum quickly reduced the region to a free-for-all of warring tribes. If Arthur held political power, it wasn’t over very many people, and it certainly wasn’t over all England. And as for the English? Ironically, those were the people he was fighting against. The people who spoke the language that became English and were the ancestors of the people we now think of as English were the Anglo-Saxons, who invaded Great Britain from mainland Europe during Arthur’s purported lifetime. Arthur himself, if he existed, was a Briton, one of the original inhabitants who had been conquered by the Romans and subsequently resisted (unsuccessfully) the Anglo-Saxons. The descendants of Arthur’s people would be today’s Welsh, not the English.

When the author writes “We know that the Battle of Badon was a real event, but what a historical Arthur might have done besides participate in this battle is anyone’s guess” (Line 9), he means to say that

(A) Arthur must have existed, because he is linked by multiple sources to a battle we know to have occurred.

(B) Arthur probably did not exist, because if he did, then he would have been mentioned in earlier sources about this battle.

(C) Although it is likely that Arthur fought at Badon, we don’t know what rank he held or even which side he fought on.

(D) It is not impossible that there were two Arthurs, one who fought at Badon and another who was a king.

(E) Even if Arthur did exist, we don’t know anything about him besides the fact that he supposedly fought in one battle.

The correct answer is Choice (E). The construction “a historical Arthur” (as opposed to “the historical Arthur”) implies uncertainty about whether Arthur existed. Saying that what he “might have done besides participate in this battle is anyone’s guess” is another way of saying that his participation in the Battle of Badon is the only fact about Arthur asserted by any of the primary historical texts. The pertinent information here is that Arthur may or may not have existed, and that if he did exist, all we know about him is that he fought at Badon. This is simply a paraphrase question, and Choice (E) is simply a paraphrase of the quoted sentence from the passage.

Choice (A) is wrong because, although both the quoted sentence and the passage as a whole indicate that if Arthur existed, then he fought at Badon, neither the quoted sentence nor the passage as a whole ever asserts that he must have existed.

Choice (B) is wrong because, although the passage as a whole does imply that Arthur’s existence is unlikely based on his absence from texts composed shortly after Badon, this fact is not a paraphrase of the quoted sentence, which is what the question is asking for.

Choice (C) is wrong because the passage as a whole establishes which side Arthur fought on at Badon (if he existed), and because, in any case, this question is not what the quoted sentence is addressing (the question is asking for a paraphrase of the quoted sentence).

Choice (D) is wrong because, while it may be possible that there were two Arthurs, this is not what the quoted sentence is addressing, and the question is asking for a paraphrase of the quoted sentence.

When the author describes early 6th-century Britain as “a free-for-all of warring tribes” (Line 17), he most likely does this in order to support the idea that

(A) a historical Arthur almost certainly did not exist.

(B) a historical Arthur would not have spoken English.

(C) the historical Arthur probably didn’t hold political power.

(D) a historical Arthur couldn’t have been a king.

(E) Great Britain had formerly been controlled by the Romans.

The correct answer is Choice (D). The context makes it clear that what is in question here is the concept of Arthur as a “king.” The characterization of early 6th-century Britain as “a free-for-all of warring tribes” is meant to support the assertion that the people were not all ruled by one man.

Choice (A) is wrong because, while the passage as a whole does seem to indicate that the existence of a historical Arthur is unlikely, the context of the quoted phrase concentrates specifically on the implausibility of anyone (be it Arthur or anybody else) being a “king” in any recognizable sense in this particular place and time.

Choice (B) is wrong because, while the passage as a whole definitely establishes that a historical Arthur would not have spoken English, the context of the quoted phrase concentrates specifically on the implausibility of anyone being a “king” in any recognizable sense in this particular place and time.

Choice (C) is wrong because, while the passage as a whole does cast doubt on the idea that Arthur held political power rather than merely a military rank, the context of the quoted phrase concentrates specifically on the implausibility of anyone being a “king” in any recognizable sense in this particular place and time. This section of the passage doesn’t establish that Arthur couldn’t have held any political office, just that he wasn’t a king.

Choice (E) is wrong because, while the passage does state that Great Britain had been controlled by the Romans, this is not the assertion that the “free-for-all of warring tribes” concept is being used to support; we already know it is true, and the “free-for-all of warring tribes” is what happened afterwards.

Which of the following discoveries, if such a discovery were made, would provide the most compelling new evidence for the existence of a historical Arthur?

(A) a text composed in 855 that definitively calls him a king

(B) a text composed in 925 that states he was born in 482

(C) a text composed in 595 that says he fought at Badon, but was not a king

(D) a monument erected soon after Badon and dedicated to an unidentified king

(E) a painting from 835 that includes a figure clearly labeled as King Arthur

The correct answer is Choice (C). The question doesn’t ask you to identify a finding that would support the existence of a historical King Arthur, just the existence of Arthur as a historical figure who lived at all (the passage already explains that it was virtually impossible for him to have been a king). The end of the second paragraph establishes that the biggest problem for historians who support the existence of a historical Arthur is that he is not mentioned in any source for about 300 years after he supposedly lived. A source that mentions Arthur and was written closer to his own lifetime would be a marvelous find for those who want to argue his existence (and a text from 595 would be much closer to Arthur’s reputed lifetime than any text we currently have).

Choice (A) is wrong because the passage states that the earliest source we have that mentions Arthur is from 828, so a source from 855 would not be earlier (and therefore more persuasive). It would be interesting that it called him a king (because the text from 828 does not), but this wouldn’t be very good evidence — it could easily be an embellishment based on the 828 text.

Choice (B) is wrong because, while specifics like a birth year are good to have, the sudden assertion of a birth year in a text from 925 would be highly suspect. If no texts from the previous 400 years mentioned the year that Arthur was born, where would a writer in 925 suddenly have gotten this information?

Choice (D) is wrong because the mere existence of an early 6th-century monument to some king wouldn’t mean that the king was Arthur.

Choice (E) is wrong because while a painting of “King Arthur” from 835 would be the earliest reference to Arthur as a king, it wouldn’t be evidence that he existed. As with the hypothetical text from 855 in Choice (A), this rendering could just be an embellishment of the text from 828.

Visual- and Quantitative-Information Questions

Questions about vocabulary and authorial intent are pretty normal stuff for any standardized reading-comprehension test. The types of Praxis reading questions we’ve gone over so far probably aren’t terribly different from what you remember encountering on tests you had to take in school. The most unusual thing about the Praxis reading test (don’t worry — we said unusual, not difficult) is that it also includes what are referred to as visual- and quantitative-information questions, which is the Praxis’s fancy term for questions about charts and graphs. Most reading and writing tests don’t do this.

There aren’t a ton of visual- and quantitative-information questions on the Praxis exam. There may only be two or three. Depending on the exam you happen to take, you may see three questions all about the same graph, or you may see one or two questions each about a couple of different graphs. But every point helps, so this section tells you about these questions.

Rethinking charts and graphs

If charts and graphs make you nervous because they seem more like math and science stuff than reading and writing stuff, the first step for you is to think about visual- and numeric-representation questions differently. The fact that visual- and quantitative-information questions are on the Praxis reading portion of the exam isn’t a mistake or the result of someone’s bizarre whim — it proves that, regardless of appearances, these questions really are reading-comprehension questions at heart.

A graph — or any kind of picture — can be thought of as a visual depiction of information that could also be presented verbally. Just as you could either compose the sentence “A horse jumps over a fence” or you could draw a picture of a horse jumping over a fence to represent the same idea, a bar graph, line graph, pie chart, or any other type of chart or graph can be thought of as verbal information presented in pictorial form.

A graph — or any kind of picture — can be thought of as a visual depiction of information that could also be presented verbally. Just as you could either compose the sentence “A horse jumps over a fence” or you could draw a picture of a horse jumping over a fence to represent the same idea, a bar graph, line graph, pie chart, or any other type of chart or graph can be thought of as verbal information presented in pictorial form.

So, relax. The visual- and quantitative-information questions are reading-comprehension questions. They’re just different.

Getting graphs

The most common type of a graph is a line graph. A line graph represents the relationship between two variables: an independent variable plotted along the x (horizontal) axis and a dependent variable (a variable that depends on the first one) plotted along the y (vertical) axis. The line running through the quadrant formed by their intersection is what you look at to figure out what value for one variable is paired with what value for the other. So say you had a line graph that plotted the relationship between “hours spent studying” and “score on the Praxis reading test” (as though everyone who studied for the same amount of time got the exact same score, which would certainly be nice …). The “hours spent studying” would be plotted with hatch marks along the horizontal axis, and the various possible “scores on the Praxis reading test” would be plotted along the vertical axis, because this is the variable that depends on the other one. If you want to know the score someone who studied for, say, five hours, would get, you’d just proceed upward from the five-hour hatch mark on the bottom until you hit the line representing the actual data, then turn and go left until you hit the corresponding score on the side of the graph.

(See Chapter 6 for more on line graphs.)

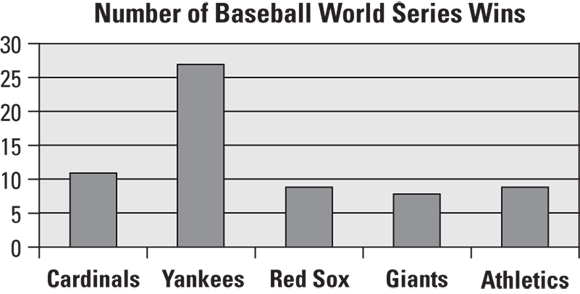

Another type of graph commonly found in Praxis visual- and quantitative-information questions is a bar graph. Rather than depicting the relationship between an independent and a dependent variable like a line graph does, a bar graph represents how different categories stack up against each other with respect to some particular idea. For example, you might use a bar graph to compare the number of World Series won by various baseball teams. The names of all the teams would be plotted along the horizontal with a bar above each name, and the heights of the bars would indicate the number of World Series each team had won, with the vertical axis of the graph hatch-marked to indicate how many championships were represented by a given bar height. The bar representing the New York Yankees would be very high (some might say unfairly high); the bars representing the St. Louis Cardinals, Oakland Athletics, and Boston Red Sox would be lower, but still respectably high; and the San Diego Padres and Texas Rangers wouldn’t have bars over their names at all (at least not as of this writing, since neither team has yet won a World Series).

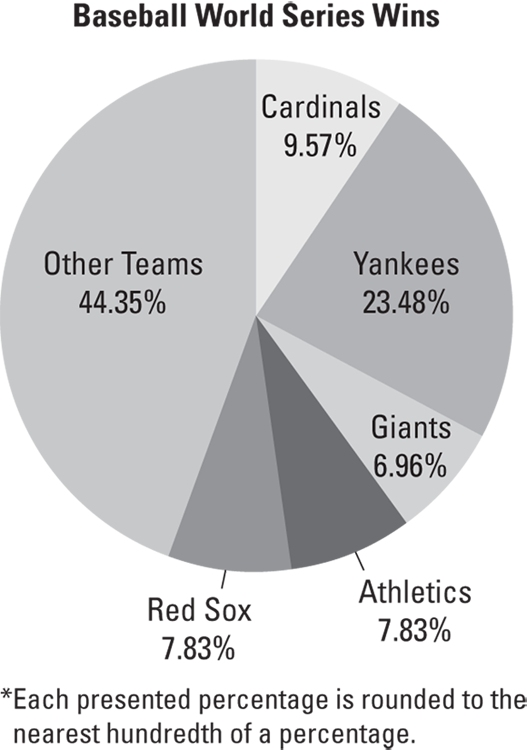

You could also plot that same information with another common type of graph called a pie chart. The difference between a pie chart and a bar graph is that a pie chart represents percentages of a total, so it looks like a circle with different-sized triangle-like pieces marked off inside it (hence its name). On a World Series pie chart, the Yankees’ slice of the pie would be nearly one-fourth of the whole pie, as there have been 115 World Series and the Yankees have won 27 of them. The Cardinals’ slice would be about one-tenth of the pie (11 World Series victories out of 115). Because a pie graph represents percentages of a total, the teams that have never won a World Series wouldn’t appear on the pie at all.

But really, there’s no sense in trying to memorize every type of chart or graph in the world. There are far too many ways to represent data visually for it to be in your interest to try and guess which types of charts or graphs will make an appearance when you take the exam. The best approach is to identify key words from the question, connect them to information represented in the graph, and then analyze the answer choices.

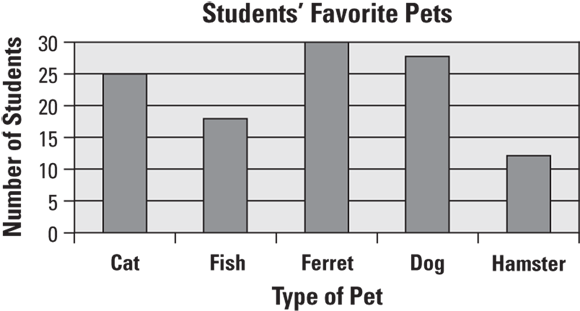

Based on the preceding graph, the biggest drop-off in popularity between consecutively ranked pets is between

Based on the preceding graph, the biggest drop-off in popularity between consecutively ranked pets is between

(A) the most popular pet and the second most popular pet.

(B) the second most popular pet and the third most popular pet.

(C) the third most popular pet and the fourth most popular pet.

(D) the fourth most popular pet and the fifth most popular pet.

(E) The drop-offs in popularity between the first and second most popular pets and between the third and fourth most popular pets were equally large.

The correct answer is Choice (B). In order to answer this question correctly, you have to think about the pets in order of most popular to least popular — that is, rank them consecutively as the question states. The biggest drop-off in popularity between consecutively ranked pets by a fairly wide margin is between cats (the second-most-popular pet, chosen by 25 students) and fish (the third most popular pet, chosen by about 17 or 18 students), with a drop-off of 7 or 8 votes. Note that the bar graph doesn’t allow you to judge perfectly how many students voted for fish, but that doesn’t matter. Whether fish got 17 or 18 votes, the biggest drop-off in popularity is still between cats and fish.

Choice (A) is wrong because cats only got two or three fewer votes than dogs, so this isn’t the biggest drop-off in popularity. Choice (C) is wrong because ferrets only got three or four fewer votes than fish, so this isn’t the biggest drop-off in popularity. Choice (D) is wrong because hamsters only got one or two fewer votes than ferrets, so this isn’t the biggest drop-off in popularity.

Choice (E) is wrong because, although it is true that the gap between dogs and cats and the gap between fish and ferrets are equally large, neither of them is the largest drop-off in popularity. It doesn’t matter that they were equally large, because the question was asking for the largest drop-off! Be careful!

Practice Reading-Comprehension Questions

These practice questions are similar to the reading-comprehension questions that you’ll encounter on the Praxis.

Questions 1 through 3 are based on the following passage.

Perhaps more so than that of any other man, his name is synonymous with incalculable brilliance in the hard sciences, and yet it is far from accurate to view Sir Isaac Newton as a model of rationalism. True, he invented calculus, laid the foundations for the science of optics, and — most famously — formulated the laws of motion and the principles of gravitation. Yet his myriad discoveries are more accurately seen as the byproducts of his boundless and obsessive mathematical mind than as the result of what today we would deem a scientific worldview: Privately, Newton spent as much time on alchemy and the search for the Philosopher’s Stone as on legitimate empirical science, and he was consumed with efforts to calculate the date of Armageddon based on a supposed secret code in the Bible. Rather than being the human embodiment of the secular Enlightenment, Isaac Newton the man was a superstitious mystic whose awe-inspiring brain still managed to kickstart the scientifically modern world almost despite himself.

1. The central idea of the passage is to set up a contrast between

(A) Newton’s brilliant scientific successes and his embarrassing scientific failures.

(B) Newton’s secret private life and his false public image.

(C) scientific methodology before Newton and scientific methodology after Newton.

(D) Newton’s scientific achievements and his unscientific worldview.

(E) how Newton is viewed today and how he was viewed in his own time.

2. As it is used in context, the word “empirical” seems most nearly to mean

(A) evidence-based.

(B) mystical.

(C) awe-inspiring.

(D) outdated.

(E) ironic.

3. It is fair to assume that part of the author’s goal in composing the passage was to encourage his readers to consider the occasional disconnects between

(A) our desire to celebrate “great” minds and our moral duty to tell the truth about them.

(B) modern public images of historical figures and their more complex real identities.

(C) humanity’s ability to reason and our dark and chaotic emotional lives.

(D) what some people are mistakenly credited with doing and what they actually did.

(E) the greatness of our modern scientific worldview and the horrors of our superstitious past.

Questions 4 through 6 are based on the following passage.

Nathaniel Essex is a serious scientist born into a comic-book world. Toiling obsessively to prove his theories, shunned by the scientific establishment for his unorthodox experiments, he stands on the brink of enlightenment or, perhaps, corruption. A fateful encounter with Apocalypse provides both. When offered genetic knowledge from outside his own timeline, Essex accepts transformation at Apocalypse’s hands, refashioning his body and mind to eliminate mortal weakness — and with it, his essential humanity. Casting off his identity as Essex, he becomes the diabolical figure known as Mister Sinister. In decades to come, he will emerge as a geneticist of unparalleled brilliance and daring, a witness to great discoveries and travesties of medical history, and one of the most dangerous opponents the X-Men will ever face.

4. The passage uses the term “corruption” to refer to all of the following actions of Nathaniel Esses Essex

(A) losing his identity.

(B) giving up his essential humanity.

(C) ridding himself of mortal weakness.

(D) becoming one of the most dangerous opponents of the X-Men.

(E) turning into a diabolical and sinister figure.

5. What life experience does the author imply may have been the basis for Essex’s decision to be transformed?

(A) failing to impress Apocalypse.

(B) suddenly appearing in a comic book world.

(C) doubting his own scientific theories.

(D) changing his name.

(E) struggling to establish himself as a successful and respected scientist.

6. Which of the following best describes the organization of the passage?

(A) A story is told, and the author’s view on the nature of what happens in it is presented.

(B) A drastic change is described, but it is also illustrated as beyond the possibility of judgment.

(C) A wish to be like a certain comic book figure is expressed.

(D) A scientific theory about a fictitious change is supported by details of a character’s life.

(E) A comic book story is reviewed with both praise and criticism.

Questions 7 through 9 are based on the following passage.

After the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, the United States needed to find an efficient way of exploring the territory newly acquired from Mexico, much of which was desert. The idea of purchasing camels and forming a U.S. Army Camel Corps for the purpose was initially scoffed at, but finally approved in 1855, and a herd of 70 camels was subsequently amassed by Navy vessels sent off to Egypt and Turkey. Ironically, however, the Camel Corps was stationed in Texas, a state that seceded from the Union upon the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. With a war to fight and no need or desire to explore territory that now belonged to another nation, Texas simply set the camels free and shooed them off into the desert. The lucky camels thrived and bred, and a feral camel population survived in the southwestern United States until well into the 20th century, occasionally causing havoc when one or more camels would wander into a town and spark a riot among the horses. The last such incident recorded took place in 1941.

7. The author’s tone in the passage can best be characterized as

(A) primarily explanatory but subtly critical.

(B) largely theoretical but consistently open-minded.

(C) primarily informative and somewhat humorous.

(D) largely analytical and mildly biased.

(E) primarily skeptical but ultimately forgiving.

8. In context, the “another nation” referred to in Line 13 is

(A) the United States.

(B) the Confederacy.

(C) Mexico.

(D) Egypt.

(E) Turkey.

9. The primary purpose of the final sentence of the passage is presumably to

(A) emphasize how large the population of feral camels eventually became.

(B) surprise the reader by linking the content of the passage to living memory.

(C) provide a hint about what finally killed off the wild camel population.

(D) definitively answer a question posed at the beginning of the passage.

(E) imply that some wild camels might still be alive in the American Southwest.

Questions 10 through 12 are based on the following passage.

Even the poorest of history students could tell you that it was Marie Antoinette who issued the oblivious response “Let them eat cake” upon being informed that the peasants had no bread — except that it wasn’t. The famous anecdote so frequently used to underscore how out-of-touch the very wealthy can be appears in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions, written in 1765, when the future and ill-fated queen of France was only nine years old and still living in her native Austria. Far from making any claims to historical accuracy, Rousseau attributes the pampered faux pas only to an anonymous “great princess” and presents it as a yarn that was old and corny even then. Presumably, the legend had been repeated about any number of European royal women for generations — but since Marie Antoinette ended up being the last queen of France, the version in which she says it was the one that stuck.

10. According to the passage, the most likely reason that the phrase “Let them eat cake” has become associated with Marie Antoinette is that

(A) she may have actually said it, although this cannot be proven.

(B) her life happened to overlap with that of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

(C) she was the final person to have her name inserted into an old joke.

(D) food shortages among the peasants reached an apex during her reign.

(E) she is the only queen of France that the average history student can name.

11. Which of the following questions is directly answered by the passage?

(A) From what nation was Marie Antoinette originally?

(B) In what nation did the “Let them eat cake” legend first start?

(C) Who lived longer, Jean-Jacques Rousseau or Marie Antoinette?

(D) Whom did Rousseau himself believe had said “Let them eat cake?”

(E) What point was Rousseau trying to make with the “Let them eat cake” anecdote?

12. Which of the following phrases from the passage is used most nearly as a synonym for oblivious, as it appears in the first sentence?

(A) “ill-fated”

(B) “pampered”

(C) “anonymous”

(D) “old and corny”

(E) “out-of-touch”

Answers and Explanations

Use this answer key to score the practice reading-comprehension questions in this chapter.

-

D. Newton’s scientific achievements and his unscientific worldview. The passage establishes that Isaac Newton was personally superstitious and a religious fanatic, and this “unscientific worldview” is contrasted with the brilliant scientific achievements he made despite this.

The right answer is not Choice (A) because the passage never alludes to any “embarrassing scientific failures” of Newton — only to private beliefs and endeavors that were unscientific. The right answer is not Choice (B) because the passage never implies that Newton deliberately cultivated a “false public image,” only that he privately believed superstitious things.

The right answer is not Choice (C) because, although science after Newton was certainly different as a result of the many landmark innovations he made, the passage is concerned only with Newton himself, not with the difference in the sciences before and after him. The right answer is not Choice (E) because while the passage points out inaccuracies in the way Newton is often viewed today, it doesn’t address how he was viewed in his own time.

-

A. evidence-based. Both in the passage and in most contexts, “empirical” means “evidence-based.”

The right answer is not Choice (B) because “empirical” doesn’t mean “mystical,” either in the passage or in most contexts (in fact, it means very nearly the opposite). The right answer is not Choice (C) because “empirical” doesn’t mean “awe-inspiring” (this is just another unrelated phrase from the passage, used as a red herring).

The right answer is not Choice (D) because although the passage characterizes some of Newton’s personal beliefs as “outdated,” the word “empirical” does not mean or appear to mean “outdated” in context. The right answer is not Choice (E) because although the contrast between Newton’s achievements and his personal beliefs is “ironic,” this is not what the word “empirical” means or appears to mean in context.

-

B. modern public images of historical figures and their more complex real identities. The passage is primarily — indeed, almost exclusively — concerned with highlighting the difference between our modern idea of Isaac Newton as an Enlightenment rationalist and the more complex truth of his status as a superstitious mystic.

The right answer is not Choice (A) because the passage doesn’t hint at anything like a “moral duty to tell the truth” about famous figures like Newton; it corrects a misconception, but it’s not an exposé as such. The right answer is not Choice (C) because the passage is about Newton specifically, not the human race in general, and it doesn’t characterize Newton’s private life as “dark and chaotic,” only “superstitious.”

The right answer is not Choice (D) because the passage never addresses anything that Newton is “mistakenly credited with doing.” The right answer is not Choice (E) because while the passage characterizes Newton as superstitious, it never brings up anything resembling any collective “horrors” of the superstitious past of humanity in general.

-

C. ridding himself of all mortal weakness. The passage discusses major changes Nathaniel Essex went through. One of the mentioned changes is presented as positive, and the others are described as negative. The two words that refer to the changes before they are described are “englightenment” and “corruption.” The author says both took place, but mentions “corruption” as what would seem to be just a negative possibility at the time Nathaniel made his decision to change. It is mentioned as a possible donwnside that ended up coming true. The positive change that is discussed must therefore be the “enlightenment,” and it is Nathaniel’s ridding himself of all mortal weakness. That alone is an improvement, a positive change.

Choices (A), (B), (D), and (E) are changes that are presented as problematic, so they are parts of the downside of the situation. They are therefore aspects of the “corruption,” not “enlightenment.”

-

E. Struggling to establish himself as a successful and respected scientist. In the second sentence, the author describes Nathaniel’s failures at being a scientist. The author also describes how hard Nathaniel was working to overcome those failures, suggesting frustration and a need to try something different. The author then immediately explains Nathaniel’s opportunity to drastically change as a scientist, indicating that Nathaniel made the decision because it would give him what he had been working “obsessively” to achieve during a period illustrated by the author to be frustrating. That is how the author connects desire and resulting frustration to a decision to majorly transform.

Choice (A) is incorrect because nothing in the passage suggests that Nathaniel had any desire to impress Apocalypse. Choice (B) is wrong because the passage does not indicate that Nathaniel suddenly ended up in a comic book world after being somewhere else. The first sentence merely describes a character who was created for comic books. It is not about a place in reality where characters can end up after some time. Nothing in the passage suggests that it is. Even if it were, it would not mean that such an unmentioned change of location had anything to do with Nathaniel’s decision to drastically change his identity, humanity, morality, name, or level of dangerousness. Choice (C) is incorrect for the same type of reason. The passage does not indicate in any way that Nathaniel ever doubted his own theories. He was working with great effort to get others to believe his theories by proving them, but that suggests he believed his theories since he thought he could prove them. Also, nothing the author says implies that there was any connection between self-doubt and the will to change. Choice (D) is wrong because Nathaniel’s name change happened in a way that described what he had become as a result of the changes Apocalypse gave him the ability to undergo. Nothing suggests that the name change caused anything. The passage says that Nathaniel became somebody else with a different name, not that he became somebody else because he had a different name.

-

A. A story is told, and the author’s view on the nature what happens in it is presented. The passage gives the story of Nathaniel Essex’s change into someone very different with a different name, so a story is told. The author provides his view on what happened by saying the change involved enlightenment and corruption. The author therefore tells a story and presents his view on what ends up happening in it.

Choice (B) is wrong because the author does not ever suggest that what happens in the story is beyond the possibility of judgment. He never indicates in any way that it cannot be judged. In fact, he judges it. Choice (C) is incorrect because the author never expresses a wish to be like Nathaniel. He never even mentions or hints at his own desires at all. Choice (D) is wrong since the passage is not about any scientific theories that exist in reality. The passage mentions the scientific theories of a fictitious scientist character, but it does not even say what those theories are, and they are just part of a fiction story. The story does not mention or suggest any scientific theories, so it could not support any, and it does not support any. Choice (E) is incorrect because the author does not indicate how much he likes or dislikes the story. He just tells it and says what he thinks it means without giving his view of the intellectual or artistic quality of it.

-

C. primarily informative and somewhat humorous. The passage is indisputably informative, and it is, on occasion, slightly humorous. Because both these things are true, there’s no real way that this answer choice can be wrong.

The right answer is not Choice (A) because though the passage is explanatory, it’s never critical. The right answer is not Choice (B) because the passage merely relates historical events; there’s nothing “theoretical” about it, and “open-mindedness” isn’t an issue.

The right answer is not Choice (D) because the passage merely relates information without analyzing anything; by extension, it can’t be biased because it doesn’t present an opinion. The right answer is not Choice (E) because the passage deals only with historical facts, not opinion or theory, so there’s nothing for it to be either “skeptical” or “forgiving” about.

-

A. the United States. From Texas’s point of view, the United States was “another nation” because Texas had seceded to join the Confederacy.

The fact that Texas itself was part of the Confederacy eliminates Choice (B). Mexico, Choice (C), is the nation to which the Gadsden Purchase land originally belonged. Egypt and Turkey, Choices (D) and (E), respectively, are merely nations from which the camels were purchased.

-

B. surprise the reader by linking the content of the passage to living memory. The author’s intent in the last sentence is to shock and amuse the reader, who will presumably be surprised to hear that wild camel “incidents” were still taking place in the United States in 1941 (in other words, in “living memory” — a phrase used to mean “within the memory of at least some people who are still alive”).

The right answer is not Choice (A) because the final sentence of the passage doesn’t imply anything about the size of the wild camel herd at any point. The right answer is not Choice (C) because, although it presumably implies that the camels didn’t survive too long past 1941, the final sentence of the passage doesn’t imply anything about how they actually died.

The right answer is not Choice (D) because there is no question at the beginning of the passage that the final sentence answers. The right answer is not Choice (E) because the final sentence doesn’t imply that some camels may have survived — if they had, there presumably would have been camel incidents after 1941.

-

C. she was the final person to have her name inserted into an old joke. The ending of the passage offers the theory that the “Let them eat cake” joke was repeated about royals for years, and that the version with Marie Antoinette’s name is the version that “stuck” because there were no more French queens after her.

The right answer is not Choice (A) because the passage definitively establishes that Marie Antoinette couldn’t have said “Let them eat cake” (the joke appears in a book written when she was a child). The right answer is not Choice (B) because, while it’s true that the life of Marie Antoinette overlapped with that of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the passage doesn’t imply that this is the reason the “Let them eat cake” story is associated with her. (Why would it be?)

The right answer is not Choice (D) because, while it may be true that food shortages among the peasantry reached an apex during Marie Antoinette’s reign, the passage does not state or imply that this is the main reason why the “Let them eat cake” story is associated with her. The right answer is not Choice (E) because, while it may be true that Marie Antoinette is the only queen of France that the average student can name (in America, at least), the passage doesn’t state or imply that this is the main reason why the “Let them eat cake” story is associated with her.

-

A. From what nation was Marie Antoinette originally? The middle of the passage makes reference to Marie Antoinette’s “native Austria.”

The right answer is not Choice (B) because the passage never answers the question of what nation the “Let them eat cake” story originated in — it implies that the story was told about “any number of European royal women for generations.” The right answer is not Choice (C) because the passage never states or suggests whether Jean-Jacques Rousseau or Marie Antoinette lived longer.

The right answer is not Choice (D) because the passage never implies that Rousseau had any belief about who “really” said “Let them eat cake”; if he presented the story as an old joke, then he likely believed that no one really said it. The right answer is not Choice (E) because, while the passage states that the “Let them eat cake” story is often used to emphasize the cluelessness of the rich, it never explains what point Rousseau himself was using it to make in the context of his Confessions.

-

E. “out-of-touch.” In both the context of the passage and most of the time, “oblivious” means “clueless” or “out-of-touch,” a term used in the next sentence to clarify the meaning of the word “oblivious” as it is used in the passage.

Nothing in the passage implies that it means “ill-fated,” “pampered,” “anonymous,” or “old and corny,” either in the context of the passage or elsewhere, ruling out Choices (A), (B), (C), and (D), respectively.

Surveying the parameters of the reading test

Surveying the parameters of the reading test Answering short-passage-based questions about the main idea, author’s tone, and vocabulary

Answering short-passage-based questions about the main idea, author’s tone, and vocabulary Mastering paraphrased, argumentative, and “if” questions related to long passages

Mastering paraphrased, argumentative, and “if” questions related to long passages Interpreting image-based questions

Interpreting image-based questions However, you’re not looking for the statement about the passage that is the most detailed or the most specific — you’re looking for the statement that is true. And there will be only one of those. The other four choices, for one reason or another, will be wrong. A common tactic the test-writers use on such questions is to make the right answer so vague or uninteresting that you barely notice it. The wrong answers stand out more. But never forget that all you’re trying to do is pick the statement about the purpose of the passage that’s true (in other words, not wrong) — no more and no less. Consider the following example.

However, you’re not looking for the statement about the passage that is the most detailed or the most specific — you’re looking for the statement that is true. And there will be only one of those. The other four choices, for one reason or another, will be wrong. A common tactic the test-writers use on such questions is to make the right answer so vague or uninteresting that you barely notice it. The wrong answers stand out more. But never forget that all you’re trying to do is pick the statement about the purpose of the passage that’s true (in other words, not wrong) — no more and no less. Consider the following example. Anyone who paid attention in grade-school science class could tell you that the five classes of vertebrates are mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and fish. For centuries, these categories made sense to scientists because they represented clear distinctions based on what we were able to observe about the animal kingdom. But now that we know more about evolutionary history, the borders between these traditional and visually “obvious” classes are not so clear. A crocodile looks more like a turtle than a penguin, but the common ancestor of the crocodile and the penguin actually lived more recently than did the common ancestor of the crocodile and the turtle.

Anyone who paid attention in grade-school science class could tell you that the five classes of vertebrates are mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and fish. For centuries, these categories made sense to scientists because they represented clear distinctions based on what we were able to observe about the animal kingdom. But now that we know more about evolutionary history, the borders between these traditional and visually “obvious” classes are not so clear. A crocodile looks more like a turtle than a penguin, but the common ancestor of the crocodile and the penguin actually lived more recently than did the common ancestor of the crocodile and the turtle. The trick, then, is to simply ignore the original word and everything you know about it. Don’t think about what it means most of the time or attempt to psychoanalyze the question by determining what the “hardest” or “easiest” thing it might mean is. Just pretend that a blank exists instead of the original word and then pick the answer choice that works best in that blank. The original word doesn’t even matter!

The trick, then, is to simply ignore the original word and everything you know about it. Don’t think about what it means most of the time or attempt to psychoanalyze the question by determining what the “hardest” or “easiest” thing it might mean is. Just pretend that a blank exists instead of the original word and then pick the answer choice that works best in that blank. The original word doesn’t even matter!