Chapter Eleven

FROM PATRAS TO ATHENS, MYTHS AND ORACLES

22 NOVEMBER - 24 DECEMBER 1809 | 25 APRIL - 23 MAY 2009

Like Byron, Hobhouse, Fletcher, Vassily, and Georgiou the dragoman, the whole party recently joined by one of the Albanian guards, Dervish Tahiri, the more compact Strathcarron entourage of the writer and his wife left Messolonghi for Patras by boat. The Byron contingent were rowed all the way on a windless day, initially through the shallows and marshes which surround the town, the Strathcarron contingent relied on dear old Mr. Perkins to chug them along thechannel, newly dug and banked through the salt fields.

On the way one still passes a waterborne village which remains much as Hobhouse described it. Shacks built on sticks rest on the water like so many wading spiders, and the fishermen surround their plots of marsh with wattle reed fences against the lapping waves. Wooden dinghies, seemingly overburdened with the paraphernalia of nets and buoys, rollers and pulleys, bob up and down at the end of these amphibious gardens. Two or three shacks have evolved into enjoying windows and doors, incongruously garish paint schemes and plastic roofs and porches. Out boarded dories are tied to a leaning post. As one glides past one automatically thinks ‘how charming’, but fears the reality would be ‘how ghastly’.

At Messolonghi I had to meet the mayor for a photo-opportunity - his photo-op, I might add. Churchill said the Greeks were five

million people with five million opinions, and as Byron was to discover fifteen years after his first visit here two Greeks who agreed about anything were seldom to hand when you needed them. Whenever one wanders into a Greek bar and is distracted by the blaring telly, hard to avoid unless one is auditorily challenged, there always seems to be the same scene playing on the screen. Across the bottom half will sit a panel of half a dozen pundits discussing the cause du jour. Above them the screen will split into close-ups of whoever is talking at the time. There are always three of them, regularly there will be four, if you are lucky five, and there’s no reason to suppose that from time to time all six talking heads will be talking heads at the same time.

I mention all this because at the meeting with the mayor there were always several conversations going on at once, various randomers like me wandering in and out, the raising of voices, and then the conciliatory gestures, the beating of breasts and then hugging of shoulders. When he had worked his way back to me, the mayor, a delightfully congenial red-hot socialist called Angelos, asked how I found Messolonghi. I said that I thought the fishermen’s shacks on the way in from the Gulf were wonderfully evocative, but this was enough to set him off on a rant about the unfair development of uncontrolled capitalism. Later I found out that some of the more commercially minded fishermen had discovered the benefits to be had from eco-tourism, and turned their shacks into bijou cabins, and hence the doors and windows, garish paint, leak-proof roofs, hammocks in porches and smart new dories. Half the mayor’s room was following the conversation, and when one of them translated it the other half joined in and pretty soon we were in a living metaphor of Greece as twelve million splinter groups who occasionally and with great reluctance form uneasy and short-lived coalitions; but the rancour has no depth, and moments later dissolves into querulousness, then apathy - but not for long! - then an opinion, then someone else’s opinion, a brief respite, take a deep breath and off we go again.

But I digress. Patras. They made the considerable detour to Patras in the hope that waiting at the consul’s house (the last British one before Constantinople) would be news and letters from England, and in Byron’s case remittances from Hanson. They had already met the Greek-born English Consul, Samuel Strané, in Malta and more recently here in Patras on their one-hour stopover eight weeks earlier, but unfortunately he had no packages waiting for them. There was, however, hope: he reported that the next convoy was expected within days, and they were welcome to lodge for as long as they liked. In the event they stayed twelve days in Patras, and only left when the convoy eventually arrived empty handed.

To spread the load of hospitality Strané introduced them to his cousin Paul, and pretty soon Byron and Hobhouse were involved in a tug-of-consuls: consuls, moreover, who represented countries at war, as on cousin Paul’s flagpole flew the colours of France, Sweden and Russia. Both consuls outbid each other to entertain their visitors, but it seems that cousin Paul pulled harder and they stayed under Napoleon’s protection, and dined on his Imperial extravagance, while waiting for the convoy.

Byron was anyway by this stage engrossed with the first draft of Childe Harold ‘s Pilgrimage, and as always his creative impulses were aroused best at night. Hobhouse, in his diary entries for his time in Patras, seems rather bored and lonely. He amused himself with inconsequential day trips while his travelling companion slept the days away and worked through the nights. At least Hobhouse - and Byron - were consoled by the return to civilisation, writing that ’after a long disuse of tables and chairs, we were much pleased by these novelties.’

Cousin Paul kept a good kitchen too, and entertained lavishly. One evening, a fellow guest, a Greek doctor, told the story of Ali Pasha and the French General Rosa. The latter had gone to Ioannina to marry. We know not why. Ali Pasha took umbrage, possibly because he had not been the guest of honour. He invited the general into his palace as a guest for further celebration, had him seized and carried on a mule to Constantinople where he died of fury and a broken heart in prison. Byron must have filed the story under ‘Plots’, for this is the DNA of Don Juan, with Ali Pasha as Lambro and General Rosa as Juan.

Patras doesn’t sound like it was a place to tarry, unless one was absorbed all night writing an epic poem or waiting for mail in a packet. The Irish traveller and writer, Edward Dodwell, who was in Greece five years before Byron, wrote that Patras

was like all Turkish cities composed of dirty and narrow streets. The houses are built of earth baked in the sun: some of the best are whitewashed, and those belonging to the Turks are ornamented with red paint. The eaves overhang the streets and project so much that those opposite houses almost touch each other, leaving but little space for air and light, and keeping the street in perfect shade, which in hot weather is agreeable, but far from healthy. The pavements are infamously bad, and being calculated only for horses; no carriages of any kind being used in Greece.

Although Greece’s third city after Athens and Thessalonica, Patras today is rather unsure of itself. Its main point of pride is its leading role in the Greek War of Independence, when in 1821 the Greek flag was raised for the first time on Greek soil. The Turks responded by razing the town, leaving only the old Venetian castle which still overlooks it, and which is now its only grace, still intact. When the Turks were finally forced out - by the French as it happens - in 1828, the city was rebuilt on a grid pattern, but the earthquake of 1953 was as devastating as the Turkish revenge and the city now retains the grid but is saddled with horrible 1950’s concrete architecture. One needs to keep one’s eyes at street level, for here can be found the bars and cafés enlivened by its large university population. It’s a city for evenings and nights and weekends, but only, one would hazard, during term time.

Before leaving Patras Byron had some housekeeping to attend to, having finally lost patience as well as too many piastres with the dishonesty of Georgiou the dragoman, who was dismissed for untold robbery and replaced by Andreas, a Greek of the English consul Strané’s employ who spoke Turkish, French, Italian and choirboy Latin. The latter he had learnt as a chorister in St. Peter’s in Rome, an item on his CV of which Byron would have approved.

If Patras has an identity crisis, their next stop, known as Vostizza to Byron, Vostizi to Strané, Aiyion in the Greek guidebook, Aigion at the port, Egio on the Michelin map, Egion in the Admiralty Pilot and Aigio to the locals has so many identities a crisis seems inevitable. The town now is entirely nondescript, the victim of two recent earthquakes and botched rebuilds. If earthquakes here are like buses in London one hopes that the next rebuild will be more sympathetic.

But stranded they were in whatever-it’s-called for over a week by foul winds. For Byron this was time well spent: the nights belonged to Childe Harold and the days to Andreas Londos, their host at Vostizza and the spark for Byron’s Greek consciousness.

Londos was the Cogia Pasha, the prime minister to Ali Pasha’s son Veli Pasha, who governed this part of the Peloponnese on his father’s behalf. At the time he was only nineteen, so more or less Byron’s contemporary, ‘tiny with a face like a chimpanzee and a cap one third of his height’. He was already a devoted student of politics. Hobhouse noted that: ‘We could in an instant discover the Signor Londos to be a person in power: his chamber was crowded with visitants, claimants, and complainants; his secretaries and clerks were often presenting papers for his signature; and the whole appearance of our host and his household presented us with the singular spectacle of a Greek in authority - a sight which we had never before seen in Turkey.’ When Byron first arrived Londos was reticent about any political discussion, as Byron was after all the guest of, and recent visitor to, Ali Pasha himself. But as the week wore on they became closer, and by the time the entourage left a week later a life long friendship between the two lovers of Greek identity had taken hold.

Twelve years later Londos led a Greek insurrection at Patras which became the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence. He was a leading figure throughout the struggle, and is now a national hero whose portrait hangs in many a Peloponnese bar and bus station, but at the time, after the struggle had been won, he backed the wrong faction in the Greek roulette of independence politics and the subsequent and inevitable civil war. He had contact with Byron again throughout the War, and Byron wrote to him that ‘Greece has ever been to me, as it must be for all men of any feeling or education, the promised land of valour, of the arts, and of liberty through the ages.’ In his journal Byron wrote that ‘Andreas Londos is my old friend and acquaintance since we were lads in Greece together.’

***

Foul winds eventually turn fair and on 14 December 1809 they hired a ten-oared galliot, hoisted a lateen sail and crossed the Gulf of Corinth from whatever-it’s-called to the north side. By the evening they had reached the charming inlet and port now known as Galaxidi, the jumping off point for Delphi. They disembarked and found an inn, where they had to ‘turn two parties out of two rooms half filled with onions’. As usual Fletcher made Byron’s and Hobhouse’s beds, before joining the rest of the entourage in the lesser room where they tucked down as best they could, although poor Fletcher was not a happy valet having ‘a cheek, tooth and headache and catching twenty lice’.

Today Galaxidi is a delightful low-key, low-rise harbour, and fully returned to the prosperity it enjoyed before the Ottoman occupation. The hilltop church - its red cupola the first sight of Galaxidi through the binoculars - welcomes one in from the southern horizon. Outer islands show the way, one even just sports a church, and others just a vineyard. Some kind soul has built a monolith on a potentially treacherous reef, and one turns hard to port after passing it and straight into the harbour.

Like Patras it played a leading part in the War of Independence, and like Patras it was revenge-sacked by the Turks for its troubles. Its history has always involved the sea, and there is now an excellent Nautical Historical Museum tucked away in the cobbled backstreets, with a replica figurehead from Cutty Sark outside. The museum’s resident dog looks like a goat, all the signs and literature are only in Greek - normally annoying but for some reason here rather refreshing - and the gift shop is now slightly emptier than it was before the writer’s wife’s visit earlier this morning.

The harbour that the Byron galliot pulled into is now the much smaller fishing harbour, a charming inlet lapping on the pavements of identikit tavernas, where the food really is a secondary consideration to the setting, peaceful in the near and spectacular in the far. Byron first saw Mount Parnassus from Vostizza on what must have been a particularly clear autumn day, and our first sight of:

Oh, thou Parnassus! whom I now survey,

Not in the phrensy of a dreamer’s eye,

Not in the fabled landscape of a lay,

But soaring snow-clad through thy native sky,

In the wild pomp of mountain-majesty!

was from the Taksis Taverna in the clarity of an early May summer morning. It was one of those occasions when Byron and the writer met through time.

As elsewhere throughout the Mediterranean the larger commercial fishing boats berths are making way for those intended for visiting yachtsmen. It’s a question of unsentimental economics: a yacht brings in more euros to a port than a trawler. The nutrient poor Mediterranean has never been rich in fish - even the Romans used to complain about poor catches - but recent advancements in fish finding technology and the flagrant disregard for conservation by the fishermen themselves has meant that large-scale commercial fishing in the Mediterranean is now financially unsupportable. The trawler fishermen we met in Greece were all Egyptians (Egypt’s fishing industry was destroyed by the Aswan Dam), and they looked like they had had enough too. There has subsequently been a revival of small-scale, almost hobby, fishing by one or two men in small open boats, and it is these dozens of skiffs and dories that now fill the Galaxidi harbour in which Byron arrived, while the larger harbour developed after the Second World War for old-style commercial fishing is smartened up and awaiting visiting yachts like Vasco da Gama.

Like Byron and the entourage we only stayed one night as Delphi beckons as powerfully as ever. Leaving Galaxidi, heading north and east the landscape changes immediately: to the west all is fertile, cultivated and populated, then just over a small ridge the valley which leads up to Delphi is barren in comparison, barely green, with boulders tumbling ominously down the slopes. One’s eyes are drawn up, and there is Mount Parnassus glowering down at her subjects below. Over the next days we are going to see a lot of each other. I don’t know if it’s something I said but she never seems to approve. There are gods galore living in Parnassus’s cleft at Delphi, Zeus himself, Apollo of course, and yet it’s the spirit of snow-capped Mount Parnassus that seems to dominate.

Long before the worshippers of Greek gods came here it had been holy ground for the Mycenaeans, and before them the worshippers of Gaia, the earth goddess, daughter of Chaos and mother of Heaven. I was looking for the mystical cleft in one of Mount Parnassus’s folds, the geological statement which once seen has explained to visitors from the beginnings of time why the gods would meet here.

And have you noticed how the gods always live in the most inconvenient places? Machu Picchu in Peru, Mount Kailash in Tibet, Mauna Kea in Hawaii, Uluru in Australia, all major expeditions, acts of faith, as if the gods want to be sure you really want to visit them. At least Zeus was less demanding: looking for the centre of the universe he released two eagles from its opposite poles, and after great flights through the ether they met on the slopes of Mount Parnassus, high above the Gulf of Corinth. Later Apollo made the site his seat, and taking the form of a dolphin (delphis) to guide Cretan sailors to him, renamed it Delphi.

Greek gods like Apollo differ from humans mainly in being immortal. For Ancient Greeks there was no afterlife; this was it. The gods had every human frailty: some were jealous, others were seductive, most could be devious, unpredictability was only to be expected, and cussedness not unknown. Perhaps it was cussedness that attracted them to Delphi.

Apollo’s worshippers built his temple to align with the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset, and within it, at the exact spot where Zeus’s eagles had met, at the navel of the planet, they set a sacred stone. Over that stone they built an inner sanctum, a temple for an oracle, and for a thousand years the Delphic Oracle, the mouthpiece of Apollo, would be consulted once every moon cycle. The oracle herself, always called Pythia, would be a fifty-year-old virgin (in greater supply then than now) at the start of her tenure and would hold the job for life. The sanctum happened to be built on north/south and east/west fault lines, and the pneuma, the breath of the earth, arising from them would induce trances to help with prophecies, which were either intentionally or pneuma-tically given as ambiguities.

In Byron’s time the only way up to Delphi was via the town of Crisso, resting peacefully below the site on Parnassus’s early slopes, and from there to take the ten-kilometre, thousand-metre-high horseback ride up to what was the village of Castri which occupied the site. Most visitors today hardly notice Crisso at all as they sweep past it on the highway which approaches the new town of Delphi, half a mile and tucked around the corner from the famous old archaeological site of Delphi itself. Byron was rather impressed with one aspect of Crisso: apparently the women were of such easy virtue that he suggested that it would have been better to build a temple to Aphrodite than Apollo. In spite of conscientious research the writer is unable to confirm.

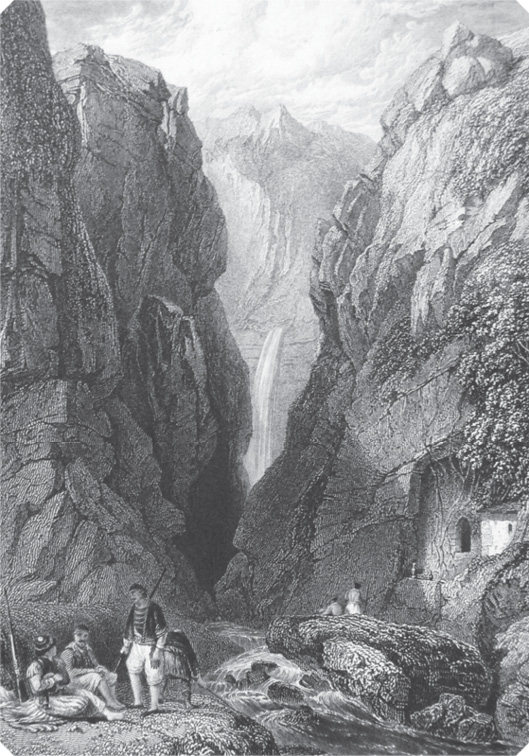

Not having a horse, and a thousand-metre climb in May being a long one for Shanks’s pony, the writer took the easy option and drove. At first all was well as the track was a road of sorts, and a bit four-wheel drive-y in parts, but I had a hire car so that bounced and groaned up just fine. But then suddenly, about half way up, a road works sign on trestles blocked the road. I had to get out and walk after all, safe at least in the knowledge my car blocking the road wasn’t going to cause a traffic jam. Actually the climb is not too strenuous with Parnassus pulling you along, and an amble on the way down with the Gulf views to settle the stomach. Wild flowers, goats’ bells and the scent of burnt almonds escort you along the track, and when you pause to take a breath the world pauses with you. Byron saw six eagles here, although Hobhouse later ruled that they were vultures.

Reading about their visit now, one has the feeling that Byron and Hobhouse were rather unimpressed by their first brush with the antiquities of Ancient Greece. Hobhouse wrote that ‘divested of its ancient name this spot would have nothing very remarkable or alluring.’ So often as one re-visits Byron’s Grand Tour one cannot help feel that the places have changed for the worse, but Delphi stands out as an exception. In 1809 the site was occupied by Greek shepherds and goatherds and their respective flocks, but they were not Greek in the Hellenic sense of understanding the word and they made no connection at all between the columns and ruins in which they grazed their flocks and among which they sheltered for the night and any ancestors. After a week of patriotic political stirrings with Andrea Londos, and then a visit to Greece’s disinherited past - a past still glorious in Byron’s Classics educated mind - we can now see in Byron’s verses and letters the first stirrings of his Greek national consciousness.

The first ancient sites they passed were the Sanctuary of Athena and Temple of Tholos and then at the base of the cleft the Castalian Spring, the very spot where Apollo prevailed, Pegasus landed, the Muses quenched their thirsts and generations of blocked poets have sought their inspiration. Byron took the powers of the waters seriously, drinking it ‘from half a dozen streamlets, some not of the purest, before we decided to our satisfaction which was the true Castalian, and even that had a villainous twang.’ A guide showed them around the ruins, making wild claims about the oracle’s domain, Byron noting that ‘a little above Castri is a cave, supposed the Pythian, of immense depth; the upper part is paved, and now a cow-house.’ Of course it was nothing of the sort.

If Byron and Hobhouse were under-whelmed by the remains at Delphi the writer must admit to being rather overwhelmed, partly because it was one of the few occasions when a modern tourist complex had been done sympathetically. The village of Castri remained on the site Byron visited until the whole complex was bought by the French government for their archaeologists in 1891. The ‘mud poor’ villagers were moved to a new place, called Delphi, half a mile around the corner. Castri was excavated and the site evolved into what we can see today. The new museum is located discreetly, the car parks are out of sight, the signs are low and explain just enough of what each ruin was, the tour guides don’t shout, the ropes guiding one along the approved route are barely noticed. Perhaps if my friends could return now they would be, well, if not overwhelmed, maybe just plain whelmed.

I had contacted a guide for the visit to Delphi, Penny Unger, a friend of a friend of Gillian’s, who had been a fellow guide at the V&A Museum and who had married a Greek and settled in Amfissa, the nearest town to Delphi. We meet in the café of the Acropole Hotel. Penny is younger than I had expected, conspicuously of childbearing age, and blonder. She wears large purple spectacles on a chain. The spectacles go on and come off regularly. Around her shoulders is a thin cardigan, on her feet sensible boots.

She could only have a cut glass English accent: ‘Now do you want to see anything in particular?’

’Yes,’ I say, ‘Lord Byron was here two hundred years ago. I have some quotes from him and some notes from his travelling companion. He was a naughty boy and carved his name in a pillar. There are some pretty good directions...’

’Ha!’ she gasps, ‘do you believe in coincidences?’

’Not normally. I’m more of a synchronicity merchant on the whole.’

’Yes, quite so, just yesterday my friend Apostolos from the municipality said we should do something special to celebrate the anniversary of Lord Byron’s visit.’

’He knows the cow’s cave, the pillar, everywhere they went?’ I ask.

’He does,’ she smiles and delves into her bag. She looks around the empty café and lowers her voice, ‘Apostolos knows everything.’Moments later she is on her mobile to him: ‘Apostolos...’ that’s all I can understand directly but am not surprised when he appears a few moments later.

We jump into Apostolos’s people carrier and soon arrive at the Castalian Springs. They are now fenced in because of the danger of falling boulders. ‘Two hundred years ago no problem one or two visitors at the Springs, now...’ and he makes signs for a land slide. We leave there and walk down to the ruins of the monastery. Several dozen pillars lie randomly in the grass. A path of sorts surrounds them. Apostolos knows his pillars and heads straight for the one with Byron’s scratched graffito. We squat down beside him. He points to some faint indentations. I move through different angles, up and down, side to side, and with the sun at a certain angle, me at another, the pillar at another, my Polaroid sunglasses on, his finger pointing precisely at a point on the pillar I can just about make out a B. Later in his office he shows me one he had prepared earlier, with a dusting of powder brushed over and yes, m’lud did indeed vandalise a pillar at Delphi.

Back at the site, after she has whisked me round the museum, in rather sprightly style for one so pregnant, I ask Penny if she felt that they had done an Elgin.

’What do you mean?’ she asks suspiciously.

’Well, it’s as if they have taken the best bits from the site and put them in the museum. Galling enough if the museum is in London,but worse here when it’s on site.’

She looks me over, as if to see if I can be trusted with a state secret. Evidently I can and she says, ‘not all the pieces are from the site. This site I mean. Some from other sites. So reproduced.’

’You mean they’re replicas?’ I ask.

’Well not exactly replicas in that sense, but there was not much left here lying around, what with the Dorians and Nero and Constantine. And then the Turks. Complete philistines. Half of Amfissa comes from here. Well not half, but you know what I mean.’

At the top of the site is the stadium where they held the Pythian Games, the forerunner to the Olympics - although the Pythians had to compete in the nude, so depriving themselves of sponsorship opportunities. At this point Penny has an earnestness attack and we part, but flippant is as flippant does.

And so the Byron entourage left Delphi for the short journey to Athens. They passed though Livadia, Thebes - now Thiva - and Skourta, ‘a miserable deserted village’ then and a miserable polluted town now, all the way without much interest or incident. If the road was unexciting then it is duller now, and the land becomes a featureless Athens suburb soon after Skourta; Thebes is particularly disappointing, there is no sign of Oedipus or his mother, still less Dionysus or his vineyard. I looked everywhere, but Thebes feels like it has never recovered from its destruction by Alexander in 335bc. Thus they proceeded through Ottoman outposts until on Christmas Eve 1809 they found an inn ten miles short of the small and unimportant provincial town of Athens, the glories of which had been the subject of so many hours of Classics study, into which they rode unnoticed and bemused the following day, Christmas Day,1809.