Sarah and Colin

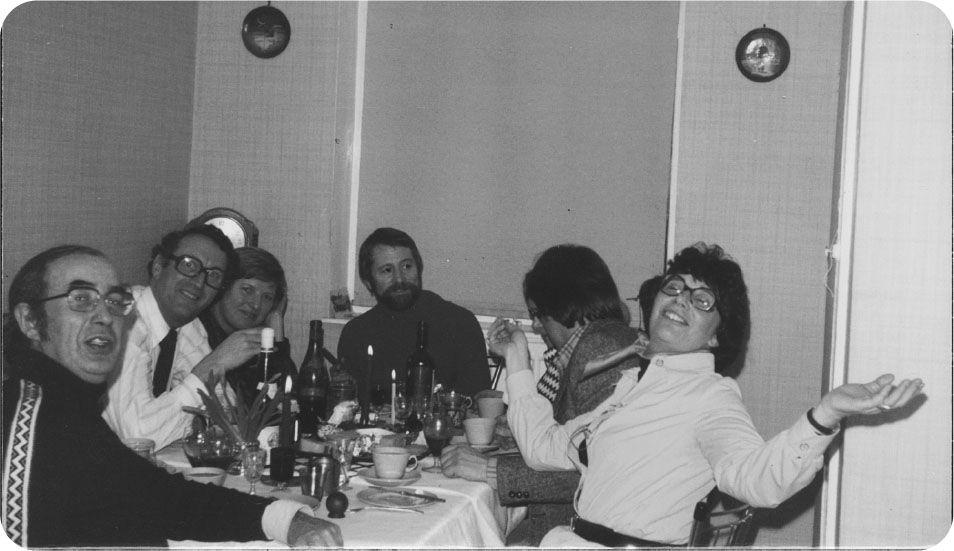

My mother’s affair had many bizarre elements. It’s hard to know which is the most bizarre. Undeniably, it leading to her turning her life, and her house, over to golf is up there. Also, the decision to tell everyone about it. But the most amazing thing, probably, about my mother’s affair with David White is that despite all this incredible advertising of the fact: I don’t think my dad ever really noticed it. It’s an astounding feat of willed self-ignorance. Not least because David White was always at our house. Here he is round for dinner:[fn1]

Here he is at my fucking bar mitzvah:

Here he is with my mum in our back garden. And frankly it’s hard not to read quite a lot into this one.

It’s hard, that is, not to assume that in this photo, David White is asking for a particular type of sexual relief, and my mother is offering to upgrade.[fn2]

He was a fixture at our house at this time. Since I do not believe that David White’s interest in my mother ever matched, or even came close to, my mother’s interest in him, I don’t think he was ever auditioning to replace my father. But this book began with a memory of him teaching me how to hit a golf ball, which is probably the most vivid one I have of him crossing that particular boundary. As it happens, my memory – which may be faulty as I also have a memory of being very good at football when I was young, which despite my commitment to truth is one I know would be strongly contested by anyone I played with – is that I hit the ball well. My memory is that it soared high in our garden. It may even have gone above the shit football goal. Perhaps David White was an exceptionally good teacher of the golf swing. But there seems something sacrilegious about this. Football was iconic in our house. It was one of the not many things at 43 Kendal Road that bound us three boys to our father. Our dad taking us to Gladstone Park every Sunday after ITV’s The Big Match was one of the very few things that felt like a family tradition. So the image of the golf ball, pristine, new, an intruder, soaring above the old broken-down but always there football goal – I’m going to call it a deeply transgressive image, redolent of David White’s world surpassing Colin Baddiel’s, although that might be reaching a bit.

Beyond his continual presence, there were many other ways in which my mother would broadcast her affair, certainly within the house. She would write love letters to David White, hundreds of them. But she would not just write them, and send them, like a normal person. She would copy them on carbon paper and leave the copies around in various places, including, on one occasion, the breakfast table. She would deliberately leave her answerphone on record while talking to David White so their conversations would be preserved. On her desk, she would stack the tiny answerphone cassettes, often labelled ‘David W’, with the date. You will be thinking, perhaps: Well, she clearly wanted her husband to know. I’m not sure. I mean, maybe, but I don’t know if that was the primary motivation. Remember, my mother was a hoarder. I think she copied the letters, and kept the conversations, first and foremost because of that. This was a woman who kept virtually everything – old keys, passports, matchboxes, thimbles, ticket stubs to golfing events, lanyards (also to golfing events) – so why wouldn’t she keep something intensely important to her, like her lover of twenty years’ words, or her words to him?

Here is one of those many, many letters:

Things to note: the inverted commas again (we will be coming back to those); the lack of guilt or fear of being discovered; the erotic prose, which goes further than perhaps anyone would like (we will be coming back to this, too); and the hint, underneath, of sadness, of this passion not being reciprocated.

I’m guessing that by now a recurring question may be popping up in your mind, that being: Did your dad really not know about your mother’s affair? When she was so blatant about it? When, indeed, the whole golf thing was just the biggest red flag (or maybe a white one, in the middle of a putting green) possible?

My mother was, as is perhaps clear by now, an intensely performative person. I rarely heard her say anything that didn’t at some level feel like she was, in some way, projecting a version of herself. But Sarah Baddiel was not a self-conscious self-dramatist – there was no sense of her ever being ready for her close-up, Mr DeMille. She was more method than that. Her part-playing involved a deeper dive. As can be seen from the forty or so years of golf memorabilia.

Just once, in later life, I heard her say something intensely authentic. Something that didn’t seem like it reflected back to her a version of herself as she would like to be seen. I remember we were standing in our front garden in Dollis Hill. It must have been the late eighties, as she wouldn’t have said this to me if I was younger. But she and my dad had just had a row. They often had rows, but I didn’t in all the time they were rowing ever hear them rowing about my mother’s infidelity. Most of the time, their rows were about very small things.

I don’t remember what this row was about. I remember only that he had been shouting, and had gone in the house and slammed the door. And my mother turned to me and said: ‘It’s so tiring, living without an emotional life.’

I still can’t believe she said this. Not because it isn’t an accurate and insightful summing up of what being married to my dad must have been like much of the time. Because it is. But my mum was not given to highly articulate introspection, to chronicling the difficult nuances of her own life. She was given to fully embracing fantasy versions of her own life in order to block out complex realities: the complex realities of the present, like living with a difficult and frequently angry man, and the complex realities of the past, like being from a family torn apart by the Holocaust. It was for me, a strange moment: like my mother had suddenly turned into Anita Brookner.

The accuracy, anyway, is the point. Colin Brian Baddiel was indeed not a man of the emotions. He was a man of science, of football, of, with his children, rough and tumble play, and of shouting ‘WHO THE FUCKING HELL IS THIS NOW?’ whenever the phone rang. Which I think is the key to understanding how he managed not to notice his wife’s affair. He shouldn’t be thought of as a threatened male, unable-to-cope-with-the-truth, using denial as a shield against breakdown if confronted with reality. It was more that my mother’s psychodramas were, for him – as almost everything was, for my father – aggravation.

And what aggravated him most was my mother and, particularly, my mother’s, and I’m afraid I’m going to have to go Yiddish here, meshugarses. This is the – probably incorrectly spelled – plural of meshugarse, which means, approximately, crazy thing/behaviour. Meshugarses is used to denote the various batshitteries that the meshugenner – the batshit person – is forever doing. But it always involves on the part of the speaker, exasperation. It never involves any element of awe or joy or ‘I love how crazy you are’-ness. The context is always, ‘Oh God, what meshugarse is this now?’

At some level, my mother’s affair, and the various obvious clues pointing to the fact of it, was just, for my dad, another one of her meshugarses. It was just another thing that was suddenly obsessing her and that therefore he wanted to have no truck with. His blinkeredness, his not wanting to have to deal with her infidelity, may have had an element of masculine wounded pride and self-denial about it, but it also had a stronger element, I would say, of ‘What the fuck is she up to now?’-ness. And when you consider that quite a lot of what the fuck she was up to involved golf, you can see he had a point.