Colin

The flip-side of what I’m calling (no doubt annoyingly – no doubt it will read to some like those people on Big Brother who used to say stuff like ‘The thing about me is that I just tell people how it is, take me or leave me’) my impulse to always tell the truth is, I think, an acute lack of judgey-ness. It is my belief that all human beings are deeply flawed, and what they present to the world, particularly now that social media has offered them the chance microscopically to curate who they are, tends to airbrush out those flaws. Which is a pity, as it is through flaws that you get to see who the person really is. It’s a cliché, but a beautiful and true one from Leonard Cohen: the crack is where the light gets in.

So it should be clear. I don’t judge my mother for having an affair. And I don’t just mean that I think – which I do – that a combination of trauma in her childhood and emotional arrest on the part of her husband need to be factored into why she did. I mean that in considering anyone’s history, the things they did that are ‘bad’ – at variance with how they ought to behave, that is, as good citizens, parents, mothers, whatever – are a source of fascination, perhaps even of celebration, if what you’re interested in is their humanity.

This always felt natural to me, but I notice nonetheless that people who came to see My Family: Not the Sitcom were sometimes shocked that a son could speak so freely about his mother’s unconventional sexual history. Similarly, some people were taken aback by my handling of the topic of my father’s dementia. The notion of this being shameful strikes me as being even less easy to comprehend than the idea of my mother’s infidelity being so. But I have spoken to people who have told me that, yes, they felt ashamed about a parent having dementia. In one case, a close friend explained that this was because they had, before he got the disease, put their father on a pedestal, and could not bear to see him so reduced. Which made me wonder if my lack of shame about my parents, whether it be related to their sex lives or their decrepitude or anything else, is linked to the fact that I never idealized them to begin with. They always seemed, or at least for as long as I could remember, entirely flawed human beings. Or to put it another way, entirely human human-beings.

Another element of this story some might find problematic would be the notion that I am revealing my father as a cuckold – to use an absurdly medieval word. Again, it would never occur to me to judge him for this. I have been cuckolded – honestly, am I in ‘The Miller’s Tale’ here? – and, even though I suppose men who are themselves medieval will jeer about how much that makes you, in Panto Male World, a loser, indeed, a cuck, like much in human relations, it’s not always that straightforward. I am very bad at breaking up with people, so when one of my girlfriends who I’d been with too long had an affair, I was overjoyed about it.

But the imaginative associations which spring from cuckold – of a nervous, emasculated, put-upon man – didn’t fit my father. Who my father was, in fact, is to some extent best expressed by talking about his dementia. In 2011, he was diagnosed with Pick’s disease, a type of frontal lobe dementia. I went with him, and my mother, to University College Hospital, to meet with a geriatric neurologist. After giving the diagnosis, he took me and my mum aside and explained that the symptoms of Pick’s disease include, along with short-term memory loss, irritability, sexual disinhibition, rudeness, inappropriate behaviours, swearing and extreme impatience.

I said: ‘Sorry – does he have a disease, or have you just met him?’

Because Colin Baddiel had always been exactly like that. When he first met Morwenna, it was at my mum’s sixtieth birthday party. He opened the door to us and growled: ‘You couple of cunts are late.’ I pride myself, as you will know, on being always very me but even I am not as me as Colin Baddiel was Colin Baddiel. If Roger Mellie from Viz had been Welsh and a bit more aggressive – that was my father. This was a man who once, on a family holiday to Devon, farted so badly in an antiques shop, we had to leave the shop. When we returned later in the afternoon, the shop was shut: and the owner had been taken to hospital.

Soon after he was first diagnosed, I remember meeting a woman called Joyce, who’d known my dad since she was a child.[fn1] When I told her he had dementia, she said: ‘I’m sorry to hear that your father is no longer inside himself.’ It’s a beautiful thing to say, but not entirely accurate, or at any rate, not in the way I think Joyce meant. What the Pick’s disease did is make one side of him – obscenity-loving, eager-to-shock, aggressive-jokey – grow like a malignant lesion, at the expense of other elements of his personality. But it had always been his dominant voice. My father was indeed no longer inside himself: he was outside himself. He, his profound he-ness, became unrestricted, exploded, all over the place.

This may be true of mental illness in general. Various members of my family have had what I believe are now called episodes – I sense you’re not surprised – and I’ve noticed that the way these play out does not usually involve the person behaving out of character. Rather it often seems as if they are extremely in character, overmuch in character. While a breakdown can be a dismantling of personality, it can also be something close to an overdose of personality. Similarly, with my father. The dementia, while diminishing many parts of him, lifted whatever inhibitory mechanism had kept his most basic self at least a bit in check, to create of him a kind of Ur-Colin, a toxic distillation of who he was.

So, the Pick’s disease did not, as dementia is thought to do, rob us of who he was, but the opposite. It turned the volume up on who he was. In my mind, he did not have Pick’s disease, he had Colin Baddiel’s disease.

Even in a house with three boys, with so much testosterone, Colin was always going to be the most male. My sense of my dad when I was young was that he pushed the category of male into something approaching that of animal. He would sometimes sleep on the floor, stretched out in contorted shapes in the middle of a weekend afternoon on the front room carpet. He had so much thick dark hair in his nostrils I found it confusing how he could possibly breathe. And he would sneeze so loudly – never achoo! always A-HOO! – it would frighten us children every time like a horror film jump scare. Once, he came in from washing the car on a cold day with a line of unnoticed snot hanging from his nostrils so long it reached down, pendulum-like, to his trousers.

His affection – real – for us was never soft: it was conveyed only in football, play-fighting and, latterly, swearing. For my father, calling me or my brothers ‘wankers’ was a term of affection. Once at a football match, he turned to me and said, of Ivor, who was innocently watching the game, ‘He’s such a pudding-face goon.’ Which, despite my deep love for my brother, really made me laugh. Much, much more than me – his son who, absurdly, would come to be seen as a standard bearer for a mainly bogus phenomenon called Laddism – my father was a superlad. Well before it was a word in common currency, he was all about the bantz.

My dad came from a working-class area of Swansea and ended up with a PhD in biochemistry from Imperial College London. In 1961, before most of the world had even heard of it, he made LSD in his lab and took four times the normal dose. Which is probably why he got dementia.

We three brothers were told this by our parents, I remember, when in our early teens. I think it was designed to ward us off the dangers of drugs. My dad said that when he took LSD he saw his brain appearing in front of him, but giant, and with parts whirring, like an enormous organic grey watermill. He didn’t use those exact words but that’s the picture he was painting, and I remember just thinking: That sounds brilliant – must try drugs asap.

My mother, incidentally, joined in this small meeting of the Dollis Hill branch of Narcotics Not Very Anonymous, telling us she had taken mescaline in her twenties, provided by my dad, from his laboratory. It appears at the time he was a British-Jewish prototype of Walter White – Breaking Baddiel, perhaps – but her visions had been all about the Nazis. She said she was able to see her room as it had been in Königsberg when she was a baby. She could see the Gestapo coming in and smashing it up. In a very my mother way, she didn’t just consider this a drug-induced hallucination. She told us she’d rung her mother and described the room she saw while under the influence of mescaline and Otti had confirmed that it was exactly as it would’ve been in 1939.

Which is impossible. It means that when she was about two months old my mum had taken in her surroundings and somehow imprinted them into her subconscious, where they had stayed for about twenty years, before being excavated via the Indiana Jones of mescaline. I know a lot of New Age people do believe we have a form of memory retention from very early on, possibly even in the womb, but those people are – how can I put this? – wrong.

It was very my mother though, again, as with the story about Arno being her real dad, to somehow glamorize her back story like this. The truth of her – of my – family’s degradation, disenfranchisement and traumatization in Germany was too impossible for her to process. And so, if her subconscious did anything at all under the influence of mescaline, it would’ve not revealed any real memory but instead created a new one: it would have made things more bearable. I know this because by that time, in 1939, my grandparents had lost everything and were living hand to mouth and I doubt very much they would have had a separate room for the baby.

By the way, they told all this not just to us, but also to Julian Cope:

I’d known Colin and Sarah since 1984, and we’d sit and talk for hours. They once told me of their experiences as LSD guinea-pigs in 1959. Sarah said she had regressed to her time in ’30s Germany and had totally freaked out. Whoa, I was impressed and freaked out myself. I’d recently refused to be interviewed for a BBC documentary about LSD and here were two lucid middle-aged people putting a real perspective on it.

Despite his dabbling with drugs, my father was not a hippy. He was not possessed of much in the way of peace, love and understanding. And he was not a reconstructed man.

Once, when I was about twelve watching TV on the sofa, I put my head on his shoulder. I remember doing this with some trepidation, knowing it wasn’t something I normally did. My dad looked at me and said, sarcastically, in a camp voice: ‘Oh, I didn’t know you cared.’ He responded, in other words, to me, his son, putting my head on his shoulder, with the suggestion that that was a bit gay (and that being gay was something to be made fun of).

This, incidentally, in all the things I’m writing about my parents here, is the only time I have felt genuinely damaged by something they did. I mean, I’m sure all the over-broadcast infidelity and the shouting and the lack of niceties and the strange takes on the Nazi past and of course the bloody golf took some sort of toll, but the point of this book, in a way, is to celebrate all that. Because, for better or worse – and as someone who likes to avoid clichés, sorry about this next phrase – it has made me the man I am. And I am absurdly comfortable in my own skin. My own skin may not be of the best – without doubt the skin itself isn’t – but the flaws and cracks are intrinsic to my me-ness, and therefore I have no reason to complain of what led to them. I wouldn’t even class them as damage, more accidental sculpture. This is what makes this book different from, say, Spare.

This moment, though, when I think of it, makes me feel … shit. The twelve-year-old me felt – feels – deeply humiliated. Because I remember how much I wanted to show him some affection – partly because I just did, but I think possibly also because I’d understood at that age that sons, somewhere, even in the 1970s, did do things like putting their heads on their fathers’ shoulders, even if none of us had ever done it at 43 Kendal Road – and his response was crushing. Even though I am a comedian, and stupidly committed to comedy, it was an early experience of how much a joke at your expense, particularly one made by someone you love, can reduce your soul to ash.

Plus, it did make me anxious about showing physical affection to my father in future. In fact, in perpetuity: for some time after, I was worried that on his deathbed, I might be prevented from holding my dad’s hand as he slipped away by the fear he might at any point open his eyes and go, ‘Oo, hello sailor!’

My dad’s PhD, written in his early twenties, is called ‘A Study of the Gaseous Reaction Between Chlorine Trifluoride and Paraffin Hydrocarbons’. It’s, if you don’t know anything about chemistry, unreadable. Here’s the abstract:

This thesis describes a study of the gaseous reaction between chlorine trifluoride and paraffin hydrocarbons (mainly methane) and an attempt has been made to elucidate the mechanism of fluorination of hydrocarbons by this interhalogen.

The first section of the thesis describes briefly the various ways of introducing fluorine into to an organic molecule. Thus an account is given, in chronological order, of the principal work in the field of direct gaseous fluorination. This includes homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions of both aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons and the researches of the main workers in this field have been discussed …

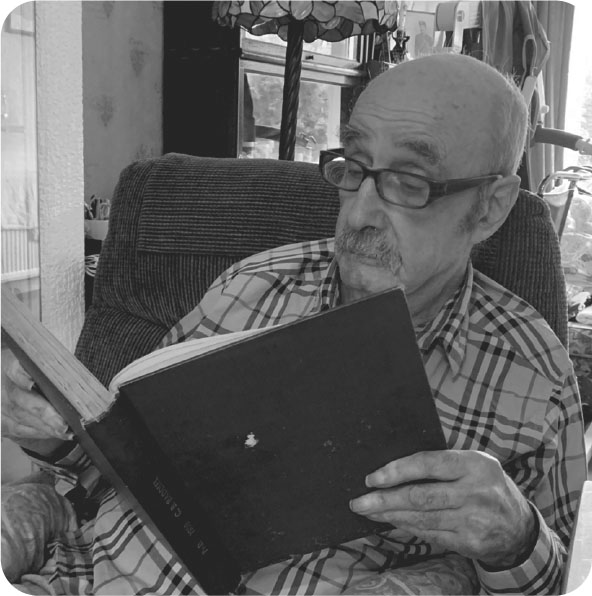

Well done if you got through more than a sentence of that. One person who could, however, was my dad. Here he is doing so:

You may think, Well, obviously your dad could read it, but I will add that this photo was taken about a year before he died, when he was deep into dementia. It’s one of the curious things about the disease that certain types of high cognitive ability persist long after most of the much smaller everyday ones that get us through the day have gone. Similarly, at a time when he didn’t know who I was, he could still beat me at chess. The poignant and sad thing is that I’d often give him his PhD to read, as he always seemed interested and engaged in reading it, but he would also always say, after a few minutes turning the pages, ‘Who wrote this?’ I once showed him his name on the title page, and he just looked confused and upset. So I never did that again.

My dad’s ideas about what was and wasn’t important intellectually – which ruled the roost in our house – were pretty inflexible. As far as he was concerned, if you couldn’t prove something scientifically, it wasn’t worth talking about. He wasn’t much given to reading us bedtime stories, or helping us with our primary school Hebrew homework, but he did have a packet of flash cards based on the periodic table, which he encouraged – that is a downplaying of his style: the word browbeat may be more accurate – us into memorizing. Each was a different element, and he’d hold the cards and say, ‘Right. Lead?’, and we would have to say what the chemical symbol was – Pb (it’s still in there) – and how many electrons and protons lead has, and its other properties, as far as we could remember. He wouldn’t, if we failed to get these facts right, beat us Dickensically (not a word), but would look very irritated, and even though he always looked irritated, it would still be obvious our ineptitude had made him more so.

Chemistry permeated the minutiae of the house. When asking for the salt at the dinner table, my dad wouldn’t say pass the salt, but pass the nackle. There’s something very indicative of who he was in that detail: NaCl is the chemical symbol for sodium chloride but it’s also a word hovering somewhere between knackered and tackle – even when being scholarly (perhaps because of being scholarly, and the sense of effete intellectualism it implies), my dad always needed to include a dash of sweariness, of overt joshing maleness.

It was expected therefore that all three of us would be scientists. Ivor drunk the Colin Kool-Aid completely, and did chemistry, physics and maths A-levels. He will not – well, I’ve asked him in advance – mind me telling you this didn’t work out brilliantly: he got two Ds and an E (and is now a successful comedy writer, obvs). I was going the same way. Parents – if they are as big characters and as primary colours in their thinking as mine – can impose a very intense false consciousness on their children. I was a teenager who regularly got As for English, history and other humanities, and Cs and Ds for chemistry, physics and maths – and yet still, because of the intellectual default imposed by my dad, was going to choose chemistry, physics and maths as my A-level subjects right up until the last minute. I only didn’t do that after a teacher, whose name I don’t remember – poor, given that this man has been crucial in my life, and in the biopic would be played by Dustin Hoffman – took me aside and pointed out that this pattern of achievement on my school reports maybe revealed which end of the intellectual spectrum my brain was best suited for.

It also demonstrates the disconnect we had at home. We were at least in one respect a very traditional Jewish/immigrant aspirational family: focused on educational achievement, specifically on reports. It was a big deal when we bought ours home, particularly for my mother, who would comb through them for As, nod at Bs, and look pained at every C and below. But not pained enough to say ‘Hold on, Dai,[fn2] based on my endless scouring of these reports – and frankly, I could be looking at them much less microscopically and still notice this – you seem to be choosing completely the wrong subjects.’

More disconnect – or frankly, just a very good example of how at this point in the 1970s the word parenting was not a word, or at least not for my parents – is illustrated by the moment I finally followed Teacher Mr X’s advice and told my dad I was going to do arts subjects for A-levels. It took me a while to build up to it. As I have said, our dad never hit us, he was never physically violent. But I feared his temper, nonetheless. We were all scared of it. When I say he was irritated all the time, this implies something niggly, tetchy, frustrated. My father’s anger was louder, fierier than that. His irritation always carried with it a sense of genuine rage. In a way my dad, like my mum, may have anticipated social media, in that everything – everything – made him go from 0–100 in angry shoutiness.

Certainly, at this age, around fourteen or fifteen, approaching his looming back as he sat at the breakfast room[fn3] table to tell him my further education plans, I was frightened of that shoutiness. I screwed my courage as best I could to whatever fragile sticking posts I had and told him my intended A-level subjects. He didn’t shout. He stayed sat at the table, looking into the middle distance. And then he said: ‘It’s a waste of a brain.’

So as I say: not great parenting. Not ‘you’re my child, follow your dreams, fly, my pretty, fly!’ Uh-uh. It’s a waste of a brain. And I guess I showed him, didn’t I? By ending up as a big successful writer/comedian guy. Except: I spend all my time now reading science books, endlessly trying to understand the mysteries of quantum physics. Which is partly because as I get older that’s the only route I have as an atheist to feeling like I’m getting close to an actual understanding of the mystery and meaning of life – or the granular reality of it, anyway. But I think also it’s a return of the repressed. I think I may as a youth have rebelled against Dr Colin Baddiel, PhD, by taking a different intellectual path, but in truth, I always, and very much now, think and thought of science as where the true cerebral work is done. Colin Baddiel settled that idea in me very young and even though I didn’t follow him into the lab (because I couldn’t), I basically think that what I’ve done in my career, including now, writing this book, as far as proper brain labour goes, is namby-pamby winging it.

In fact, science didn’t really work out for Colin Baddiel either. He had hopes of doing something amazing in research and may well have had the aptitude for it, but circumstances, including having three children in his twenties, meant he took a middle management job at Unilever, running a laboratory in Isleworth. Which may not sound too much like giving up on your science dreams, except the laboratory’s job was to test rival companies’ products, using mass spectrometry.[fn4] That may still not sound too much like giving up on your science dreams, except that the products concerned were shampoos and deodorants. It did at least mean that in all the time I lived at home, I don’t think we ever had to buy any shampoos or deodorants. We just had a series of mysteriously unbranded cans and bottles marked ‘Project 54’ or similar.

When Colin Baddiel was in his early forties, Unilever closed the Isleworth lab. They offered him another job but in Port Sunlight in Liverpool. At the time – me, Ivor and Dan were all teenagers by then, and all our friends were in London – no one wanted to go. Now, I wonder if it might in fact have been interesting. We didn’t have the internet then, so it wasn’t possible as it is now to google and discover that Unilever in 1928, in Port Sunlight, had created around its plant a utopian idea of a workers’ village.

Instead of going to Liverpool, Colin took voluntary redundancy. I think he assumed he’d get another job in science quickly, given that he had a PhD in chemistry, but he reckoned without him being my dad: without, that is, being someone who would be rude and truculent in interviews and didn’t own one reasonably smart suit. Two years later, he was still unemployed. During this period, he – both my parents, but mainly Colin – became completely obsessed with money, in the sense of not spending any. This is not unreasonable, given his circumstances, but to be honest, that was the default at 43 Kendal Road even when my dad did have a salaried job. And indeed before: after he died, his one-time best friend Lionel,[fn5] whom I’m named after – David Lionel Baddiel is my full name – told Ivor and me some stories about our father we didn’t know, including that our parents had gone to stay at Lionel’s house in Thornbury for their honeymoon. Perhaps this clarifies what I was saying earlier about how my mother might have felt she’d missed out on her glamorous phantom parallel-universe life in Germany.

But it – Colin’s miserliness – went into overdrive when he lost his job. Throughout the early eighties, my father would go apeshit if anyone left a light on anywhere in the house. He wouldn’t let us have friends back in case they, and I quote, ate some toast.

Some of this anxiety about money I now see as related to his background. My dad’s dad, Henry Baddiel, was a tinker: he sold cloth in Swansea from door to door. He and my grandmother Sylvia lived in a terraced house with an outside toilet. My dad had a twin brother, George, who died in childhood. Sylvia (a woman, like my mother, of some thwarted ambition: she was a brilliant classical pianist, having spent a year at the Royal Academy of Music before marrying Henry and, I always got a sense somewhat bitterly, departing London for Swansea) once told us the story about how my dad cycled back from school waving the results that meant he’d got into university, and she cried while telling it, perhaps because she was just sad that time had passed, but also I think because she was remembering the force of that scene, of a moment that meant her son would not be spending his life scraping to exist just above the bread line. As she cried, my dad was doing a lot of raising his eyes to heaven and saying, ‘Yes, yes, we’ve heard it all before’, because the story of his own escape from poverty was also aggravation.

But even given that time creates in me a sense of forgiveness I didn’t have as a teenager, when frankly I was just pissed off I couldn’t have friends back in case they ate some toast, my father was at this point in time properly mental about money. Which is what makes his interaction with Michael Barrymore even more startling.