Dementia

As I say, at this point my father didn’t have dementia, or at least, had not been diagnosed. He was sixty-seven when Dolly was born, a fact that causes me some anxiety, as the already-mentioned contraction of time as you get older means that I feel Dolly’s birth (which at the time of writing was twenty-two years ago) to be something that happened yesterday. And I am fifty-nine. Which means that tomorrow, I will wake up and be eighty-one.

But even without my father’s diagnosis, I had of course noticed a change in him: noticed, that is, that he was repeating himself, asking questions he had just asked, losing stuff. The Pick’s disease part of it came later. The first symptoms were the first symptoms. The same as they always are.

He never once acknowledged it. It’s clear to me from working with various organizations like the Alzheimer’s Society what the good default is. I’ve seen it in the promotional, consciousness-raising films. It is a person who recognizes they have the disease and, alongside their loved ones, comes to terms with it, with some poignant background music. Trouble is, none of those people in these films look or feel like Colin Baddiel. A man who, after all, was in denial his whole life was never going to come to terms with this diagnosis. It’s so tiring living without an emotional life. What my mother, in her moment of insight was pointing to there was that my father, a very intelligent man, did not have much in the way of what’s called emotional intelligence, but would better be called emotional articulacy. In truth, for men, particularly of my father’s generation, the inability to talk about emotions is really about fear, a fear of appearing unmanly. Because the first realization, before the window of awareness has closed, that you may have dementia is terrifying, and the first thing you need to do with fear, emotionally, is admit to it. My father’s intelligence gave him no tools to negotiate that terror, and so he just shut down.

As I mentioned earlier, my mother didn’t play the expected role either: she was never the default, good, dementia sufferer’s spouse. She became a member of a local support group in Harrow, which was made up mainly of the wives of men living with dementia. She told me and Ivor most of the meetings consisted of these women declaring to the group how much they loved their husbands, and how much they were going to be there for them throughout the trials of dementia, no matter how bad it got. My mother meanwhile was keen to tell the group she was, in her words, ‘fucking furious’. She told us she had stood up and said that one of her friends had a husband who was ninety and who was totally fine and played golf – yes, bloody golf – every day, and, not to put too fine a point on it, why couldn’t she have one like that?

In truth, my mum was furious for much of her life that my dad was my dad, and not David White, so she was never going to be that patient about becoming his carer. It didn’t help that his particular form of dementia meant he became more my dad, not less. But I admired her honesty, as she told it. I admired her crashing through the support group virtue signallers and telling her truth, especially as, in other parts of her life, she’d never quite known what this truth was.

One of the things about having a parent with dementia is it makes you more hypervigilant – and not in a good way – about your own memory. The standard cognitive decline that comes with age (what a depressing opening to a sentence) becomes constantly measured in the (declining) mind against whatever slippage you’ve set yourself that would mean ‘Oh Christ, this isn’t standard cognitive decline.’ I have several regularly moving goalposts here. For example: older people reading this book – OK, don’t laugh, there might be some younger ones – will know that the first thing to go is names. As a result, I have a bank of names – included in them are such diverse characters as Melanie Blatt, Gil Scott-Heron and Colin Farrell[fn1] – who I use as a kind of memory checklist against which non-dementianess can be judged. No doubt the day will come when I will not be able to remember the name of the person who wrote and performed ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’. Let alone who the bloke in Ballykissangel was. But for now, they remain etched into the increasingly sloping cliff of my mind, to which I can fasten my ‘I’m still OK’ crampons.

Then again, dementia isn’t just about memory. Any confusion, particularly around your normal routine, can make you feel your cognitive quota has started to expire. For example, every night, usually, before I go to bed, I put my clothes in the laundry basket. Which means, I go over to the laundry basket, holding my dirty clothes under one arm, I lift the lid on the laundry basket and I throw my clothes in there. But recently, before I put my clothes in the laundry basket, I went to the toilet first, holding my dirty clothes. I lifted the toilet seat and threw my clothes down the toilet.

This made me so depressed and convinced I already had dementia that for a while I stood there just thinking, Fuck it, I’m going to flush.

Similarly, about a year ago, I was on a plane and wanted to watch a movie, but I couldn’t find the headphones that had been given out at the start of the journey. I knew the flight attendants had handed me a pair, but they were nowhere to be seen. I’d dropped them under the seat or something – I just couldn’t find them anywhere. Then I noticed the bloke next to me had fallen asleep with his headphones on his lap. I considered what to do. He was fast asleep. It seemed a shame for them to be lying there, unused. The child within me – always so near the surface – felt a sense of unfairness about the situation. So, gingerly, I reached over to his headphones – I was only intending to borrow them – and, almost as soon as my fingers touched them, he woke up. Somewhat shocked, he said: ‘What are you doing?’ I lied – which as we know never works out for me – and said, ‘Sorry, I thought these were my headphones.’ And he said, ‘Your headphones are on your head.’

These are obviously what are called, with sometimes irritating reassurance, senior moments. But as time goes on, it’s harder to spot the moments becoming hours, becoming days. I’m wary of speaking about this too much. This might seem to contradict my commitment to self-declaration but there is a bit of a smudge on all that, which is to do with fame. I’ve said already that fame distorts who you are. But it also distorts what you say. When I first started doing interviews with journalists, I would speak as I do naturally; that is, without filter. But then I realized my own lack of filtration didn’t extend to the presentation, and indeed reception, of my answers.

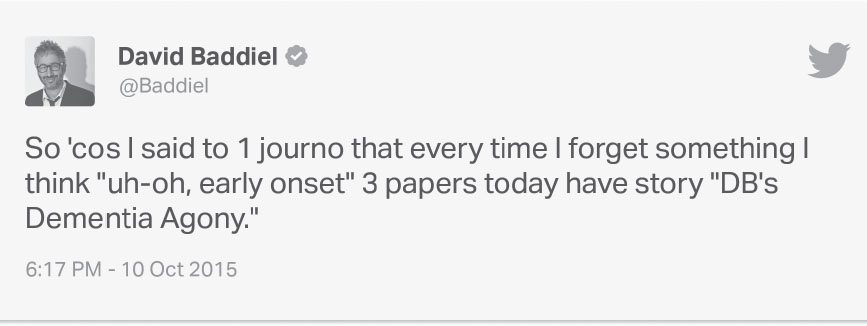

You learn many things the hard way through being in the public eye, and one of them is that illness is a scoop. In 2015, I was doing an interview with the Daily Mirror about a new kids’ book I had written. I’d done a few warm-ups of My Family: Not the Sitcom, and talked a little about my father’s illness in public. The journalist asked me a lot of questions about it. I was hesitant. I said: ‘I think if I talk about my father’s dementia, you’ll take it out of context and highlight it in the wrong way and besides, this is an interview for a book I’ve written in which some twins discover a magic video game controller, so I’m not sure banging on about my dad’s dementia is very on-message.’ But she kept asking. Eventually, as a mollification, I said something I thought was very bland. I said, ‘Well, one thing I can tell you is, because of my dad, every time I forget something now, I get a stab of fear, thinking, Uh-oh, early onset.’

It’s not truly a very original thought: everyone I know whose parents have dementia monitors their own forgetfulness. The interview ended and I thought no more about it, until that weekend when the Mirror piece on my new children’s book, about how it’s really a jolly romp for nine- to twelve-year-olds, came out:

I’m sure my publishers, HarperCollins, could do some market research to find out how many copies of The Person Controller sold off the back of this piece. Possibly none. Possibly some were even returned.

This article came out on a Saturday morning. By Saturday evening … well, I’ll show you:

By the time we get to the Express, I’ve started to forget names. It’s getting worse:

By the time we get to the Mail, I’m in agony:

It was everywhere.

I immediately started getting concerned phone calls, including from my dad’s friends. Some of whom I had in fact spotted signs of dementia in, so I wanted to say, ‘No, I haven’t got dementia, you’ve fucking got dementia …’

One particular tabloid headline that took my notice ran in the Star:

This seems an odd sentence construction. Surely it should be: I’ve already started to forget names. Perhaps the Star was trying to imply that as my brain atrophies I become more Jewish. In which case the headline should really have been ‘I’ve started to forget names already’.

Note, by the way, the photoshoot a lot of them have used. I don’t remember this photoshoot – obviously: I’ve got dementia – but clearly the picture editors at the various newspapers have chosen it because in it I look old. And mad.

The next day, I wrote a piece in the Guardian about how I didn’t have dementia. Which was designed to put the record straight. Here is the headline:

Great. Except they used this fucking photo:

Which is the worst one of the lot. What am I doing in that photo? That’s what Jenni Murray, the former presenter of Woman’s Hour, used to do in her photos:

To illustrate my article making it clear that I am in fact of sound mind, they’ve chosen a photo where I look like an insane cross between Jenni Murray and Alan Yentob.

Obviously, I also attempted to close this thing down on Twitter. As soon as I realized it was getting out of hand, I tweeted:

Which was asking for trouble, as someone called @DazBoot immediately responded: