Sarah

One of the positives about both my parents being hoarders is that, if you are going to do a show or a book about them after their deaths, you will find, in their house, a lot of material. I discovered many things while clearing out their stuff. Normally, at this point in a memoir, when talk comes to discovery, of things found in drawers and attics, it’s time for a twist, a surprise, a secret revealed. This didn’t happen with my mother. Everything I found only confirmed who I already knew her to be. Like, for example, this suitcase, which sadly neither me nor Ivor could find room for, so we took to the local recycling plant (OK, let’s call it the dump).[fn1]

But some of what I found confirmed her so deeply, it turned the corner into surprising. Some of it was so her, it surprised even my sense of her.

For example, you couldn’t tell my mother anything. No matter how much we asked her not to bring our children meningitis toys – to maybe bring them fewer toys, not huge boxes obviously siphoned from St Luke’s Hospice shop, perhaps even to buy them single nice items from a proper shop – she never did. Similarly, a corner of her collection, away from the golf memorabilia was, unfortunately, those offensive toys called – I’m going to avoid the full offensive term – gollies. She used to have loads of these up on shelves in the living room. Ivor and I often begged her to destroy them, particularly given that one of her granddaughters, Dan’s daughter Dionna, is dual heritage, but she wouldn’t listen; she just thought they were ‘great fun’. I said, ‘No, a bouncy castle is great fun, these are icons of race hate …’, but it made no difference. Once, I played the nuclear option. To try and make her understand, to feel what those dolls truly represent, I searched on the internet to see if I could show her a toy that might be equivalently antisemitic. Unfortunately, the only thing I could find were these:

Orthoducks Jews. Which she thought were great fun.

Late in the day, about a year before she died, the racist toys did vanish from the shelves. We thought that she’d finally thrown them out, but one of the first things I found while beginning the long and challenging process of going through her things was a drawer containing two of the bastards. Even death couldn’t shift my mum’s opinion.

It ramped up, the finding-things-after-death challenge. I have talked about my mother anticipating social media, mainly in her psychology, but it turns out also in the arena of the sexy selfie. I found a number of these not-very-well-secreted in her drawer. The question, of course, has to be asked: who took them? I find it hard to believe she was particularly good with a camera timer. It could have been my father.

You might be thinking at this point, Well, please, David, don’t show us these. And perhaps I shouldn’t. Perhaps I should just stick to the head shot.

I should be clear, however, the rest of the photo shows nothing more graphic than anything you might see today on Instagram. And there is another reason why it’s hard to leave the full picture out of this book. As sometimes happens with a sexy selfie, there’s a prop involved, to help the sexiness along. I wonder if you can guess what it is.

Which revelation I think would also lead us to conclude that it was not my dad but another regular male visitor to our house who took this photograph.

Yet even the sexy selfies were not the most challenging item I found buried in the vast amounts of Sarah Baddielia in my parents’ house after her death. That would be this, found at the bottom of a drawer in her desk:

It seems just like a note book, perhaps a school book, or something she used for bookkeeping the ins and outs of business at Golfiana. But no. It’s a book of poetry. It’s called Feelings.

I suspect it’s named after the Morris Albert song from 1974, but I can’t prove this. It is dedicated ‘For My MDW’, which would be Mr David White. And actually, it isn’t ‘Feelings, For MDW’. If you look closely you’ll see it’s ‘Feelings’, ‘For My MDW from SB’. We shall come back to this punctuation.

As with many examples in this book, you may feel uncomfortable with me including these apparently private poems for public perusal, but I am also fairly sure, given that, as you can see, she wrote the word ‘Copyright’ on it, and editorial notes throughout, such as ‘Page 29 as 1?’ – and because there are typed-up copies of some of the poems elsewhere – that my mother would like to have published Feelings. I have to say I am glad that, at least when I was younger and less comically distanced from all this, she never managed to do that. Because it is a book of erotic poetry. At times, very erotic poetry. Dedicated to her lover. Which would have been a complicated thing for the fourteen-year-old me to see on the shelves in Foyles.

It was, in truth, not an uncomplicated artefact to find in 2015. I read it. There are many poems. Here’s the first one, which is straightforwardly romantic:

She ticks this poem, at the bottom, in pencil. Which I love – the idea that my mum was proofreading these and thought: That one definitely makes the cut. Actually, from a quick flick through, all of them seem to have ticks. Anyway. Here’s the second one … a kind of haiku:

Which frankly, I think is pretty good. Or at least, certainly as good as anything you’ll see written on a fridge magnet. Tick.

The poems clear up a number of issues. If anyone isn’t certain that the DW referred to is David White of Golfiana (the original one), for example, this one, which begins …

… kind of clears up any ambiguity on that issue by the end:

Personally, I think my mum is doing herself down a bit here. I feel, given her transformation into Golf Queen happened rapidly after meeting DW, that she already knew quite a lot about the game of golf by the time this poem came into being. Most of the poems, I notice, are written on the emotional back foot and give a sense that DW is not being particularly forthcoming, with his presence, time and/or love. So it may well be that this is my mother trying to appeal to DW in the best way she knows how. The way to a man’s heart – well, this man’s heart – is through the offer of a long evening impressionably listening to his expertise on bunkers and flop shots.

Sometimes, he does show up, and my mum is absurdly grateful:

Although the writer in me has a need to query whether, because this is a poem, it shouldn’t be:

When I thought you would be

Miles away in Turnberry.

But then again, that might be conventional of me.

The poems are sad. They are full of desperate and lost yearning. This is one of many that, without having the literary qualities of ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ or Ben Jonson’s ‘On My First Son’, is still heartbreaking in a way:

There is something noticeable about these poems for me, which is: there is no sign of any solace at all coming from my mother’s home life. She just aches for David White, hungers and thirsts for him. Not only does she find no comfort in her children, we don’t even get a mention. So much so that reading this one, I found myself thinking (even though the spelling makes it plain she is referring to the bright star in the sky that warms the earth), Well, your son wasn’t actually many miles away, he was in the next room. He was in the next room, listening to you while you, as this one makes clear …

… are shouting his namesake.

So obviously, the poems bring up some ‘feelings’. But as ever, there is comedy to hand. Which is particularly useful when the poems become more, um, candid.

I referred earlier to my mum’s tendency to overuse inverted commas as a sort of mum-ish thing to do. This tendency crops up a fair amount in Feelings. Here it is, in fact, around the word ‘Feelings’:

Now, interestingly that is arguably a correct use of inverted commas. Insofar as obviously, feelings here is meant to have a double-meaning, made clear – a bit too clear – by the use of the words ‘penetrating me’.

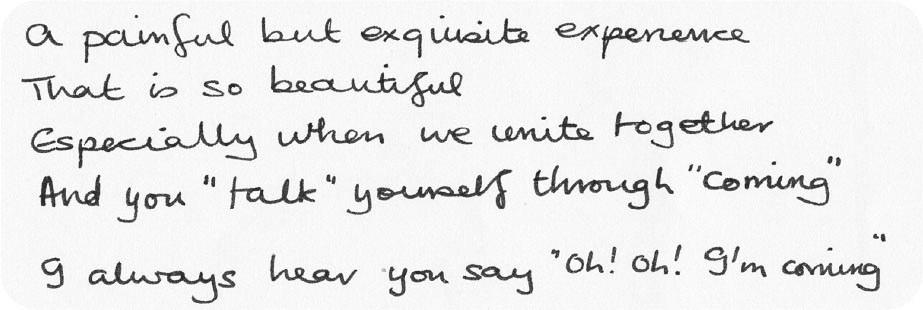

But in other poems, her usage isn’t quite so on track. Another contains these reasonably standard erotic lines, again playing on the suggestion of sex:

But it continues in a way that is not so standard. And indeed not so suggestive.

OK. So. Let’s just go back again to my grammatical points about the use of inverted commas and my mother’s misunderstanding of them. You use inverted commas when you want to indicate that you mean something other than what the word normally means. But when she says ‘talk’ here – she means talk, doesn’t she? She means words are emerging from David White’s mouth. And ‘coming’ – well, we know what she means. She means that David White is speaking while orgasming.

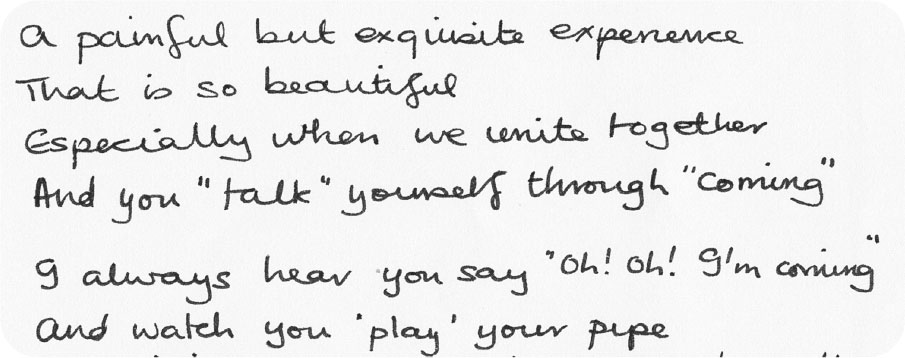

It’s a very sexual sentence, but there is no double entendre involved, no double meaning. But clearly my mother was concerned her meaning might be ambiguous, because in the next line, she … clarifies:

And then to put the tin lid on it:

And pipe, please note, is not in inverted commas. Which is extraordinary. Because that’s the word that should be. Because I assume by pipe, she doesn’t mean his actual tobacco-filled meerschaum – or whatever the fuck pipe it was. I assume David White wasn’t actually smoking his fucking pipe while he was fucking her. I assume she means – this sort of pipe:[fn2]

There’s much, much more. Fasten your seat belts for this next poem.

Again, there is a basic misuse of inverted commas here. ‘Grope’ simply does mean grope here. If she was going to put inverted commas around a word in this line it should be ‘cloak’, as cars don’t have cloaks. Unless the car in question – David White’s or hers (a Citroën DS 21, if the dates are what I think they are) – had an all-weather cover.

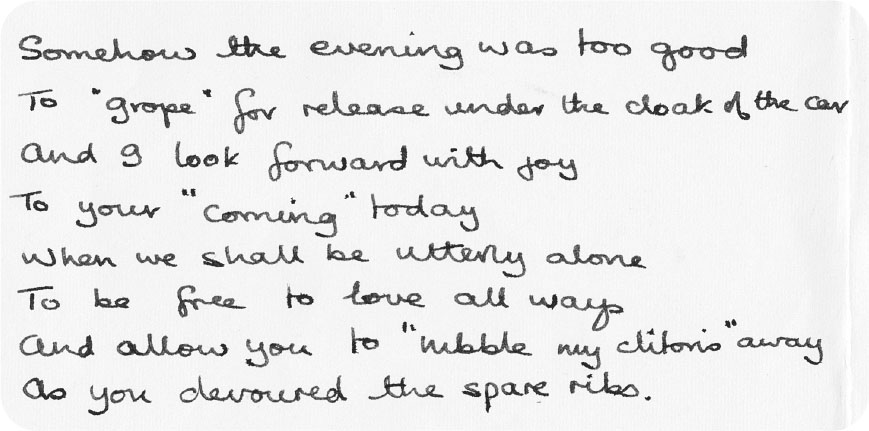

The poem continues:

Now ‘coming’ here is actually – hooray – the correct use of inverted commas. Because the word can of course mean, simply, arriving. But – wink, wink – it can also mean spunking up through your pipe. So therefore, in this usage, we have a double meaning – coming is an innuendo, a euphemism.

But then straight away follows what I think of as the pièce de résistance of my mother getting inverted commas wrong.

There is – I think this is perhaps an understatement – a lot to unpack there. I mean, just for starters – although I imagine it wasn’t a starter – the sudden intrusion into the poem of spare ribs. To be fair, there has been mention in an earlier stanza of the joy of sharing ‘excellent food, wine and company’, but I think the reader may have assumed this to have been a private repast cooked at home,[fn3] not an all-you-can-eat blowout at TGI Fridays. Then there is the strange, floating – grammatically, and indeed visually, on the page – ‘away’. I think my mother perhaps meant ‘nibbling away at my clitoris’ but felt that somehow the adverb didn’t belong within the inverted commas – that it would disturb the purity of the phrase ‘nibble my clitoris’, and we certainly don’t want to do that – so she moved it. But in so doing she creates an image that is frankly too troubling for me to express. And this is a book which, let’s be honest, in most places, goes there.

Obviously, though, the money shot – as it were – is just the phrase itself. It’s the use of the fantastically twee word ‘nibble’ juxtaposed with the frankly less twee word ‘clitoris’. But for me, it’s primarily about the extraordinary misuse of inverted commas. ‘Nibble my clitoris’ is my mother’s greatest work in that regard, elevating, in my opinion, the misusing of inverted commas to the status of art.

Because, let’s face it, ‘nibble my clitoris’ is not a euphemism. It’s the opposite of a euphemism. Thank God my mother didn’t write the previously mentioned Carry On films. No, Sid, ‘Let’s not call it Carry On Dick, let’s call it Here’s My “Erect Penis”. That’s much clearer.’