Coda: Me

After my mother died, I wrote to David White. As we know, I had his email. I said:

Hello David

I hope you’re well. I’m writing to let you know – in case you don’t already – that my mother passed away, suddenly, on the 20th December last year. She was of course very much in love with you for much of her life, so I thought you should know,

yours

David Baddiel

He replied:

Dear David – Thank you for email; I really appreciate your thoughtfulness. Yes, I had heard the sad news about Sarah and shed many tears. Only rarely am I in London these days, as I live now in eastern Europe. I last saw her in London last July around the time of The Open Golf Championship. At that time I was staging a golf art exhibition in a Museum Street art gallery and Sarah took the time to look in on me, albeit rather briefly. I could see then just how unwell she was, though she bravely dismissed any suggestion that it was anything to ‘worry about’. Poor Sarah, she had a rough time health wise toward the latter years, though I do believe she lived her life to the full …

My sincere condolences to you and the family

Sincerely yours – David W

I like this, in general. I think it shows, unlike the correspondence and the tapes I have in my possession, David White being considerate of my mum. When I sent it to my brothers, I said that I thought it was sweet but that he had not, of course, taken the bait. Meaning that despite my bald statement of the facts – that my mother had been in love with him for most of her life – he had not owned that or responded to it in any way.

Looking at it now, I realize I was wrong. Do you see it? That ellipsis. Those three dots after ‘she lived her life to the full’. I hadn’t spotted those before. I don’t know David White, except through my mother’s bizarre refraction, and yet that feels, from what I know about him, so him. I can hear him taking out his pipe and saying it, perhaps with a glint in his eye, and a wink.

I am a different generation to David White: he, in his own way, like my father, is not a man comfortable with emotions. As when my dad said, ‘That’s a load of bollocks’ about not loving his sons, you must perhaps read between the lines of David’s email. Or in this case – and let’s not forget, he is the one who got inverted commas right – in the punctuation.

I am happy with this email. Unlike my younger brother, who replied: ‘Fuck David White.’ Which is also of course what my mum would have wanted.

Early in this book, I discussed Erica Jong’s mantra about how fame means that many people will have the wrong idea of who you are. But fame just multiplies a malaise that exists for all of us, because no one has the right idea of who you are. You don’t have the right idea of who you are. There is a romantic hope that that’s what love is, the feeling of being genuinely seen. But conversely, when we are in love, that’s possibly when we most mistake the other, because we put so much hope into an idealized version of them. Point being, most of the time, we are all just getting everybody else wrong.

Fame makes it worse, however, and because everyone is kind of famous now, truth, at least the truth of personality, has become more and more unstable. Social media is a great constant oscillating exhibition of people getting each other wrong. At one end, people are putting out curated – therefore not true – versions of themselves; at the other, they are viciously attacking other people by creating versions of them so cartoonishly negative that they won’t be true either.

The only way to combat untruth is with detail. To be more specific, with idiosyncratic detail. The more detailed and the more idiosyncratic the presentation of who you are can be, the more it works as evidence. As truth.

This is what I’ve been trying to do with this book, building my parents’ identity with an accumulation of idiosyncratic detail, so that as near as possible – and it’s still of course partial and contrived and mediated – you the reader have a concrete sense of who they were.

There is one joyful side effect of this approach, which is when a version of me is presented to me that is wrong, I have a fair bank of idiosyncratic detail with which to refute it. Or to put it more simply: I can fuck up the assumptions of trolls with the weird specifics of my life story. For example, in 2017 Boris Johnson called Jeremy Corbyn a ‘mutton-headed old mugwump’. I tweeted about this. At which point a man called Frank Watson, convinced he knew best, decided to take me to task:

You haven’t read much Billy Bunter, have you Baddiel? Which allowed me to post:

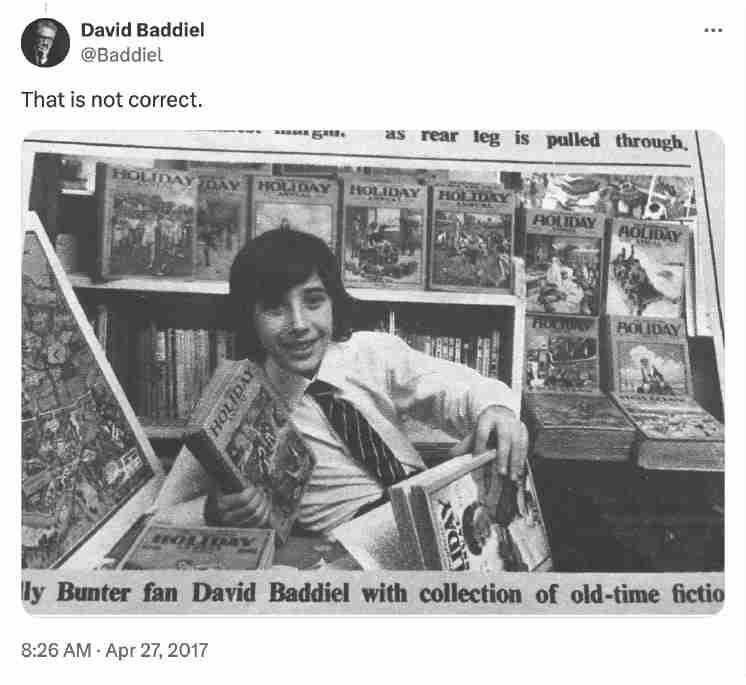

And attach to the tweet, this photo:

Which is me in The Young Observer in 1975, with my collection – entirely provided by my mother, of course – of Billy Bunter Holiday Annuals.

A response on Twitter that got 3.5k likes, and was described by the Irish News as:

‘Own’, in case anyone doesn’t know, means to put someone in their place – to win, basically. I am very against Twitter binaries, and particularly the way that nuance and debate on there has devolved into primitive crowing and shouting over who wins and who loses. Truth is not a matter of winning and losing. But fuck that. I’m very glad to think of this as the greatest Twitter own ever. I’m particularly glad that it was provided for me by something that symbolizes everything about my early life. Finally, my strange mad damaging childhood paid off. Thank you, Mother.