[ ONE ]

Evolution of a SUPERSPECIES

EVER SINCE our species appeared on Earth, human beings have gathered around a fire to fulfill our most elemental human need—companionship—as we reaffirm kinship and tribal bonds, recount experiences, share insights, and ponder the great questions that have troubled us for so long:

Who are we?

How did we get here?

Why are we here?

Where are we heading?

Our answers to those questions are profoundly rooted in place—think of the Inuit in the Arctic, the San of the Kalahari Desert, the Aboriginal people of Australia, and indigenous populations from coastal rainforests to prairies to mountainsides throughout the Americas. Over millennia, countless stories, songs, and dreams have expressed the multitude of ways the human mind has imagined the world into existence.

In the distant past, accumulated experience, observation, and insight shaped the answers to our ancient questions and thus created the way we perceived the world. According to the Haida of the Northwest Coast of North America, Raven picked up a clamshell and dropped it on a beach in Haida Gwaii, and from it emerged the first human beings. The Norse creation myth tells of the giant Ymir, whose body became the land; his blood became the oceans, his bones the mountains, and his hair the forests. Obviously, creation myths are not meant to be taken as literal history. The real meaning of or lessons within our creation myths are often buried in layers of elaboration, superstition, and metaphor and therefore may seem too incredible to be taken as more than fantastic stories.

Humans gather together and learn the meaning of the universe, our cosmology.—BRIAN SWIMME, cosmologist

I am a man of science, and today science is the source of the powerful insights that have become part of the modern narrative of how we got here. But the creation stories emerging from that science seem as far from our everyday experience and every bit as fantastic as myths of the past, and the real significance for us must be teased out of the arcane language.

Imagine a beginning 14 billion years ago in which the entire universe was contained within a single point the size of a period on a typed page. Consider the Big Bang, an explosion at such a high temperature that matter could not exist. As immense clouds of swirling gases cooled in the expanding universe, however, they condensed into particles of matter that thenceforth defined the basic physical rules throughout the cosmos. It confounds our imagination to think that vast clouds of atoms, drawn together by gravitational pull, eventually coalesced into countless stars that suddenly ignited their nuclear furnaces to light up the heavens in a cosmic instant.

And the scientific depiction of the evolution of life on Earth is inspirational, a saga of resilience and adaptability: after hundreds of millions of years on a sterile planet, one cell arose in the ocean that out-competed all others to become the mother of all life on Earth. Her descendants invaded every nook and cranny of the planet, as they transformed themselves into countless species in an ever-changing environment.

Early in the history of life, Nature began to shape new species to fit into habitats already occupied by other species. Never since the Archaean Period has a living thing evolved alone.—VICTOR B. SCHEFFER, zoologist

Human beings appeared on the plains of Africa 150,000 to 400,000 years ago, when woolly mammoths, sabre-toothed tigers, and giant sloths still flourished and the savannahs of Africa were filled with animals in numbers and variety beyond anything we know today. There was little in the appearance of our distant ancestors to suggest the explosive change we would undergo as we left our African birthplace to populate every part of the globe in a mere 150 millennia. I doubt that any other species would have trembled at the sight of our ancestors and whispered, “Watch out for those two-legged, furless apes. They’re going to take over the planet.”

We were not an impressive species in numbers, size, speed (an elephant can outrun the fastest human on Earth), strength (a chimpanzee weighing a hundred pounds could whip me and probably you too), or sensory acuity (I know if I were swinging through the trees on a vine, without glasses, I’d smack into a tree and probably fall to the ground to be eaten by a sabre-toothed tiger). The secret to our success was invisible, the two-kilogram organ encased in our skulls.

The human brain conferred a massive memory, insatiable curiosity, and remarkable creativity, qualities that more than compensated for our lack of physical or sensory abilities. And that brain had become aware of itself, conscious of its presence in time and space, capable of imagination and dreams. We observed; learned from accidents, mistakes, trial and error, and discoveries; remembered what we had experienced; recognized causal relationships; and came up with innovative solutions to problems.

The brain evolved in a biocentric world, not a machine-regulated world. It would be therefore quite extraordinary to find that all learning rules related to that world have been erased in a few thousand years.—WILSON, ecologist

Drawing on our experience and knowledge, we dreamed of our place in the world and imagined the future into being. By inventing a future, we could look ahead and see where dangers and opportunities lay and recognize that our actions would have consequences in that future. Foresight gave us a leg up and brought us into a position of dominance.

Our creation stories and origin myths provided answers to those eternal fireside questions. Distilled from generations of observation and insight, they were carefully nurtured and handed on to those who followed, providing meaning and insight into their lives.

Throughout human existence, elders have been the repository of experience, of knowledge painstakingly acquired over centuries about our origins, our purpose, and our destiny. And now I too am an elder. Within the span of my living memory, which encompasses stories from the lives of my grandparents that reach back to 1860, cataclysmic changes have taken place in society and the world.

Elders are not “senior citizens”... They are wisdom-keepers who have an ongoing responsibility for maintaining society’s well-being and safeguarding the health of our ailing planet Earth.—ZALMAN SCHACTER-SHALOMI, rabbi, and RONALD S. MILLER,writer

I was born in 1936 in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, where both of my parents were born as well. My parents named me David Takayoshi Suzuki—David, a powerful name given to me by my father, who feared I’d be a small man surrounded by Caucasian Goliaths; Takayoshi, meaning filial piety—respect for elders—conferred on me by my father’s father; and Suzuki—Bellwood in English—the biggest clan in Japan.

Both sets of my grandparents were born in Japan in the 1860s. The population of the world had reached 1 billion only a few decades earlier, passenger pigeons still darkened the skies, and Tasmanian tigers stalked the Australian landscape.

Canada was born when my grandparents were infants, Japan was casting aside almost three hundred years of feudalism of the Edo Period to embrace Western industrialization in the Meiji Restoration, and virtually every technology that we take for granted today—from telephones to cars, plastics, antibiotics, and computers—was still to be invented.

Dad’s catch on the Vedder River, 1940

My mother’s parents newly arrived in Canada

[ OUR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE PLANET ]

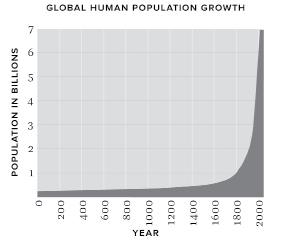

Within my living memory, the human relationship with the planet has transmogrified—we have become a force like no other species in the 3.8 billion years of life’s existence on Earth. And the ascension to this position of power has occurred with explosive speed. It took all of human existence to reach a population of 1 billion early in the nineteenth century. Since then, in less than two centuries, it has shot past 6.8 billion.

Each time the population doubles, the number of people alive is greater than the sum of all other people who have ever lived, but now we are also living more than twice as long as people did in the past. We are the most numerous mammal on the planet, and our numbers and longevity alone mean that our ecological footprint is huge; it takes a lot of air, land, and water to meet our basic needs.

In the twentieth century, cheap, portable, energy-rich fossil fuels greatly increased our technological capacity, further amplifying our ecological footprint. While it once took months for First Nations people to cut down a giant cedar tree, today one man and a chainsaw can do it in minutes. Modern fish boats stay at sea for weeks, loaded with radar, sonar, freezers, and nets big enough to hold a fleet of 747s.

Ever since the end of World War II, we have enjoyed and come to expect a never-ending outpouring of consumer goods. Indeed, after the terrible shock of 9/11, Florida governor Jeb Bush, brother of the U.S. president, stated that it was Americans’ “patriotic duty to go shopping.” A global economy built on supplying that ever-expanding consumer demand exploits the entire planet as a source of raw materials.

As a result of our numbers, vast technological muscle power, exploding consumption, and global economy, the human footprint can be seen from a plane kilometres above the earth—in the huge lakes stretching behind dams, vast areas of clear-cut forests, massive farms, and immense cities criss-crossed by straight lines of roads, encased in a dome of haze, and ablaze with lights in the depth of night.

When man becomes greater than nature, nature, which gave him birth, will respond.—LOREN EISELEY, anthropologist

Throughout the history of life on Earth, living organisms have interacted with and altered the chemical and physical features of the planet—weathering rock and mountains, generating soil, filtering water as part of the hydrologic cycle, sequestering carbon as limestone, creating fossil fuels, removing carbon dioxide, and adding oxygen to the atmosphere. But those processes took millions of years and involved tens of thousands of species. Now one species—us—is single-handedly altering the biological, chemical, and physical properties of the planet in a mere instant of cosmic time.

We have become a force of nature, a superspecies; and it has happened suddenly, with explosive speed. Not long ago, hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, drought, forest fires, even earthquakes and volcanic explosions were accepted as “natural disasters” or “acts of God.” But now we have joined God, powerful enough to influence these events.

Although our creative abilities have led to impressive technologies, they have often been accompanied by costs that could not be anticipated because our knowledge of how natural systems work is so primitive. When theoretical physicists discovered that splitting atoms would release vast amounts of energy, that process was harnessed to create the atomic bombs that exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki and brought World War II to a quick end.

But when the bombs were detonated in 1945, scientists didn’t know about radioactive fallout, which was discovered only when bombs were exploded on the Bikini atoll years later. More years passed before scientists discovered that explosions set off electromagnetic pulses of gamma rays that knock out electrical circuits, and years after that, scientists realized that debris thrown into the atmosphere from atomic explosions might block the sun’s rays and induce nuclear fall or winter.

When Paul Müller discovered that DDT kills insects, his employer, Geigy, recognized the potential for profit by using it as an insecticide. It appeared that the molecule had little biological effect on organisms other than insects, and Müller won a Nobel Prize for his discovery in 1948. As the use of DDT was vastly expanded over huge areas, birdwatchers began to notice a decline in bird populations, especially raptors such as hawks and eagles. Eventually, biologists tracked down the cause: as a result of the high concentration of DDT in the fatty shell glands of the birds, eggshells were becoming thinner and often broke in the nest.

Then extremely high levels of DDT were found in the breasts and milk of women. The explanation was a phenomenon called biomagnification, or the increase in concentration of a substance as it moves up the food chain. Thus, while an insecticide might be sprayed at low concentrations, micro-organisms absorbed and concentrated the molecules. When the micro-organisms were eaten by larger organisms, concentration was amplified again. So in top predators like raptors and humans, pesticide concentrations could be hundreds of thousands of times greater than when the pesticide was sprayed. No one predicted biomagnification, because it was discovered as a biological process only when birds began to disappear and scientists tracked down the cause.

And so it has gone as we apply new technologies, only to find later that they have unanticipated side effects. New technologies unleash perturbations that become a kind of experiment within the biosphere, as we will no doubt learn with genetically modified organisms. Our ignorance is vast, but human beings have become such a powerful force that we are altering the life-support systems of the planet.

[ EARTH ]

Conservation is a state of harmony between men and land. By land is meant all things on, over, or in the earth. Harmony with land is like harmony with a friend: you cannot cherish his right hand and chop off his left. That is to say, you cannot love game and hate predators: you cannot conserve the waters and waste the ranges; you cannot build the forest and mine the farm. The land is one organism.—ALDO LEOPOLD, ecologist

The biosphere is the layer of air, water, and land where all species live. It is extremely thin. If Earth were shrunk to the size of a basketball, the layer of topsoil on which our food is grown would be a single atom thick. And on that thin organic mix, humanity’s survival rests.

Soil is a creation of life, as dead and decaying micro-organisms, animals, and plants are added to the matrix of clay, sand, and gravel. Along the central plains of North America, soil was built from the annual contribution of leaves falling from deciduous forests, prairie grasses, and droppings from vast populations of passenger pigeons and bison. The flood plains of northern China, the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia, and the Nile River enabled the growth of great civilizations. It takes centuries to create a centimetre of soil in the richest areas. But modern-day farming practices are depleting in decades what took nature tens of thousands of years to create.

We denigrate soil as “dirt,” but it is a living community of organisms. It is a world that we barely know. In a single teaspoon of soil, we may find hundreds of millions to 3 billion bacteria and a million fungi, like yeast and moulds. There is a veritable zoo of creatures in soil, from microscopic fungi, bacteria, yeast, protozoa, rotifers, and roundworms to creatures on the edge of visibility, such as mites and springtails, to the larger woodlice, earthworms, beetles, centipedes, slugs, snails, and ants, and finally to the giants, including moles, rabbits, and other rodents.

The different groups perform services that keep soil alive. Bacteria and fungi decompose matter into detritus, which earthworms ingest and excrete as soil nutrient. Worms rummage through massive amounts of soil, enabling water, air, and organic material to percolate into the matrix.

Dryland ecosystems, which are defined by the amount of annual rainfall they receive, range from arid (less than 200 millimetres of winter rain) to semi-arid (200 to 500 millimetres winter rain) and hyperarid. These areas receive so little precipitation that the evaporation rate is far greater than the amount that rains. Nevertheless, dryland ecosystems provide crops, fuelwood, and livestock, but they are particularly vulnerable to degradation into desert. In 2000, a third of all people lived in drylands, 10 to 20 per cent of which were already degraded (that’s 6 to 12 million square kilometres). Desertification is occurring in 70 per cent of drylands.

Each year, an estimated 24 billion tons of topsoil is lost throughout the world, in large part because of agricultural practices and desertification. The amount lost over two decades is equal to the entire cropland of the United States. Annually, that represents a lost productivity worth over $40 billion.

[ AIR ]

Beyond the air there is only emptiness, coldness, darkness. The “boundless” blue sky, the ocean which gives us breath and protects us from the endless black and death, is but an infinitesimally thin film. How dangerous it is to threaten even the smallest part of this gossamer covering, this conserver of life.—VLADIMIR SHATALOV, Soviet cosmonaut

The atmosphere supports all terrestrial organisms with life-giving oxygen, is the source of weather and climate, and is a critical part of the hydrologic cycle. It is easy to think of the atmosphere as reaching all the way to the stars, and while it does extend 2,400 kilometres away from Earth’s surface, 99 per cent of its mass is within 30 kilometres and 50 per cent is within 6 kilometres. The first 11 kilometres is called the troposphere, the zone where all life is found and weather occurs.

Oxygen is a highly reactive element, the agent of oxidation, or rust, so before life appeared on Earth, chemical reactions would have scrubbed any oxygen from the air. The primordial atmosphere before life appeared is thought to have been made up of free hydrogen, carbon dioxide, water vapour, and possibly methane and ammonia, air that would be toxic to animals like us.

It was photosynthesis that altered the balance of air’s ingredients, as plants took up carbon dioxide to construct the basic molecules of life’s architecture. The energy in photons from the sun was transformed into chemical energy that could be used when needed. In return, oxygen was liberated and over millions of years transformed the atmosphere into what it is today.

Now we are altering its chemistry by spraying vast quantities of chemicals from planes and emitting gases from our chimneys, exhausts, and vents. All of humanity is burning fossil fuels at unprecedented rates and adding greenhouse gases in quantities greater than at any other time in all of human existence. Greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapour occur naturally, while more potent molecules like CFCs are synthesized by us. They allow sunlight to penetrate the atmosphere but, like a blanket, reflect infrared (heat) wavelengths back onto Earth’s surface. The continued addition of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, thereby thickening the blanket effect, is projected to have potentially catastrophic ecological consequences.

In nature, everything is connected, so as more heat-trapping gases are added to the atmosphere, polar ice sheets begin to melt, ocean waters warm and expand, and terrestrial ecosystems begin to change as animals and plants move in order to remain within their temperature comfort zone.

[ FIRE ]

The sun is the primary source of energy for the enormous web of living things. Through photosynthesis, plants capture sunlight and convert photons of energy into stable molecules of sugar, where the energy is tied up in chemical bonds. In a miraculous bit of biological alchemy, plants inhale carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, add water from the soil, and, with energy from sunlight, create chains and rings of carbon that are the backbones of all the large carbon-based molecules of life. Just as our car gas tanks store fossilized sunlight in oil, plants can store sunlight as chemical energy in sugars for use later when needed. Animals can also parasitize that stored sunlight by eating plants (herbivores) or eating animals that eat the plants (carnivores). Thus, the web of living things is built on photosynthesis to exploit the sun’s gift of energy. In any organism, oxygen “burns” the sugar by breaking the chemical bonds between carbons, sticking on oxygen to make carbon dioxide, and liberates sunlight’s energy. We are the sun, and this allows us to metabolize, move, grow, and reproduce.

Humanity has co-opted, or taken over, more than 40 per cent of the photosynthetic activity on the planet. We may replace wild organisms on land with crops grown for our own use or for our domestic animals or remove the photosynthetic potential by flooding, burning, or developing areas. As we destroy or exploit that photosynthetic energy, other species are deprived of it. Since we are a single species out of some 10 to 30 million species, we have clearly become bloated beyond all balance. The challenge and opportunity will be for us to allow much more of the photosynthetic activity to return for use by the rest of life while we find other ways of recovering energy through photovoltaics, windmills, tide power, geothermal energy, and so on.

We now know that photosynthesis is a critical factor in the removal of carbon dioxide from and contribution of oxygen to the atmosphere. So long as the carbon-based molecules created by photosynthesis are stored in the structures of trees and other plants, then that carbon remains bound up, or sequestered, and out of the atmosphere. Thus, the protection and preservation of photosynthetic activity must be an important consideration as we try to minimize the impact of climate change.

[ WATER ]

Oceans cover 71 per cent of Earth’s surface. And their water flows like a giant conveyor belt in great currents around the planet and helps stabilize planetary temperatures by absorbing heat in equatorial areas and releasing it in the northern or southern regions. In polar regions, supercooled water sinks deep into the ocean and then flows very slowly, cooling the surrounding depths as it moves. Like forests on land, marine plants absorb and sequester about half of the carbon dioxide taken up by living organisms and harbour much of Earth’s biodiversity. And the diversity of living organisms has created numerous cultures based on those creatures. Japanese culture would be radically different without seafood, as would that of numerous First Nations along North America’s coasts.

When I was in high school in the early 1950s, a teacher told us that the oceans teem with life in such abundance that we couldn’t catch them fast enough. (It almost seemed like we had to catch more and more or the fish would take over the ocean.) Those fish provide limitless protein, she said. That may have been true in the ’50s, but it is certainly not today. The human population has more than doubled since then, and that fact alone has escalated demand for fish and dramatically reduced fish populations. But our powerful new technology and our ability to take vast quantities of fish in ever more remote areas have also contributed to that decline. Marine biologist Boris Worm has calculated that if we do not radically change our ways, by 2048 there will be no commercially viable fish species left in the oceans.

Today’s global fishing fleet boasts large vessels equipped with technology that enables the boats to stay at sea through all kinds of weather for weeks at a time and range over immense distances. Fibres in fishing nets are so strong that two huge trawlers can drag heavy rollers along the bottom of the deep and trail nets that are big enough to hold several jumbo jets. In the quest for specific target species, fishers often discard more than twice as much fish as “bycatch,” species that are either considered worthless or not allowed to be sold.

Until they were outlawed, tens of thousands of kilometres of drift nets held at the ocean’s surface by floats captured animals indiscriminately—including squid, fish, turtles, birds, and mammals. The nets were curtains of death. Now banned, drift nets have been replaced by longlines, ropes that are kilometres long and hold thousands of hooks, which capture targeted fish as well as sharks, turtles, and birds.

The ocean surface is used as a highway for immense vessels, such as cruise ships carrying thousands of people and supertankers transporting oil. Deliberately or accidentally, they dump or spill waste and garbage into the water and introduce alien species transported in ballast water.

Entire cities also use the oceans as dumping grounds for raw sewage and chemical effluent, while runoff from farmland washes pesticides and fertilizers into the sea, creating “dead zones” that lose oxygen and become toxic to life. Dead zones are increasing in size, duration, and number in all the oceans of the world. It is symbolic of our thoughtlessness that the capitals of Canada’s two coastal provinces, Halifax in Nova Scotia and Victoria in British Columbia, dump raw sewage into the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, respectively.

Time... is growing short. Nature’s machinery is being demolished at an accelerating rate, before humanity has even determined exactly how it works. Much of the damage is irreversible.—PAUL ERHLICH, ecologist

Plastic and garbage tossed into the ocean end up in huge oceanic gyres where currents flow in giant circles and centrifuge the material into immense islands of debris. Some islands are bigger than the state of Texas. The action of waves, water, and sunlight breaks down much of the plastic into nurdles, small, fingernail-sized bits that are perfect for animals like albatross or turtles, which are programmed to eat anything that size. Autopsies reveal sea animals’ stomachs crammed with such plastic pieces.

The interface of the oceans’ surface with air is the largest area on the planet. Evaporation and absorption mean that atoms and molecules flow back and forth at the interface. As we burn ever-greater quantities of fossil fuels, carbon dioxide levels are rising in the atmosphere and hence even greater quantities of CO2 are entering the water, where it forms carbonic acid. Consequently, the oceans are becoming more acidic, and acidification interferes with the development of many forms of life that use calcium carbonate to build protective shells. That puts at risk such animals as oysters and crabs as well as many forms of plankton, which are the very basis of the marine food web.

[ BIODIVERSITY ]

The vast tapestry of plants, animals, and micro-organisms is the source of all we need to survive. Plants create our oxygen-rich atmosphere and remove carbon dioxide by photosynthesis, and the sun’s energy captured in the process provides the energetic molecules that our bodies use to move, grow, and reproduce. Plant roots, fungi, and the micro-organisms in soil filter water as it percolates through the earth. Every bit of the food that we require to nourish our bodies was once alive, while the carcasses of dead organisms release their macromolecules to create soil in which life grows.

Yet today we are tearing at this web of life, which is the source of our most fundamental needs, by driving an estimated fifty thousand species to extinction every year. It is humbling to realize that if our species were to go extinct overnight, biodiversity would rebound around the planet. In contrast, the loss of an insect group such as all ants would result in a catastrophic collapse of terrestrial ecosystems.

The current global extinction spasm threatens entire ecosystems as well as individual species, and the most vulnerable organisms are those predators such as whales, tigers, and grizzlies at the apex of the food chain. There is no predator higher on the food chain than us.

There is no escape from our interdependence with nature; we are woven into the closest relationship with the Earth, the sea, the air, the seasons, the animals and all the fruits of the Earth. What affects one affects all—we are part of a greater whole—the body of the planet. We must respect, preserve, and love its manifold expression if we hope to survive.—BERNARD CAMPBELL, anthropologist

[ CRISIS ]

For most of human existence, we were local tribal animals who didn’t have to worry whether there were people across an ocean, over a mountain, or on the other side of a forest or desert. We lived with what we had in our local environment. Even with the simplest of implements, people were able to take too much, extirpating slow-moving, easily caught animals or cutting and burning too many trees. Human migration may have been motivated by ecological degradation as much as curiosity or social conflict. Over time, those left behind had to learn to live in balance with the surroundings of their own tribal territory.

We now draw borders around our territory, from our own property to cities, provinces, and nations, and we’re prepared to fight and die to protect those boundaries. But now we exist in a different relationship with Earth.

Today, for the first time, we have to ask, “What is the collective impact of all 6.8 billion people in the world?” As we continue to cling to the primacy of our borders, we fail to see that air, water, seeds, and soil that blow across oceans and continents, or migrating fish, birds, mammals, and insects, pay no heed to human

priorities.

In contrast to the way we view our surroundings, every aspect of the natural world is interconnected. Thus, for example, we fragment the world into areas like economics, energy, health, and environment and try to manage them separately. But the kind of energy we use has immense repercussions in the air, water, and land, which in turn have a huge impact on human health and thus the economy.

Our great crisis of climate change demands a radically new approach. We must act as a single species to deal with global problems that transcend borders and acknowledge the rules and limits that nature defines. We must also act in the best tradition of our species, which has been to use foresight based on our knowledge and experience. And today we have the amplified ability to look ahead with scientists armed with supercomputers and global telecommunications.

In 1992, 1,700 senior scientists from seventy-one countries, including 104 Nobel Prize winners (more than half of all laureates alive at that time), signed a document called “World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity.”

Their opening words were an urgent call to action: “Human beings and the natural world are on a collision course. Human activities inflict harsh and often irreversible damage on the environment and on critical resources. If not checked, many of our current practices put at serious risk the future that we wish for human society... and may so alter the living world that it will be unable to sustain life in the manner that we know. Fundamental changes are urgent if we are to avoid the collision our present course will bring about.”

They went on to list the areas of collision, from the atmosphere to water resources, oceans, soil, forests, species, and population; then their words grew even more dire: “No more than one or a few decades remain before the chance to avert the threats we now confront will be lost and the prospects for humanity immeasurably diminished. We the undersigned, senior members of the world’s scientific community, hereby warn all humanity of what lies ahead. A great change in our stewardship of the earth and life on it, is required, if vast human misery is to be avoided and our global home on this planet is not to be irretrievably mutilated.” The document concluded with a list of the most urgent actions to be started immediately.

This is a frightening document, especially when you consider that scientists of such stature do not readily sign such strongly worded statements. The failure of the media, politicians, and corporations to respond to their warning means we are turning our backs on the survival strategy of our species—look ahead, identify the dangers and opportunities, then act accordingly to avoid the hazards and exploit the opportunities.

The crisis is real, and it is upon us.