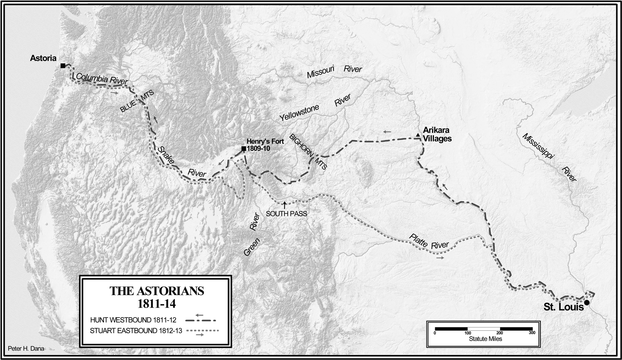

“We began to notice more particularly the great number of drowned buffaloes that were floating on the river,” John Bradbury wrote on April 16, 1811. “Vast numbers of them were also thrown ashore, and upon the rafts, on the points of the islands. The carcases had attracted an immense number of turkey buzzards, (vultur aura) and as the preceding night had been rainy, multitudes of them were sitting on the trees, with their backs toward the sun.”[1]

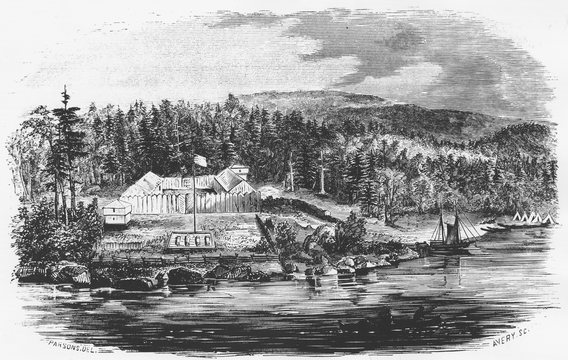

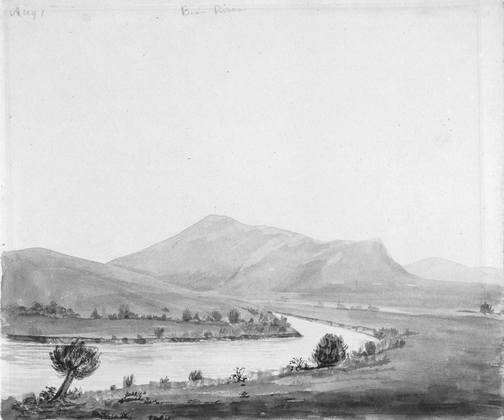

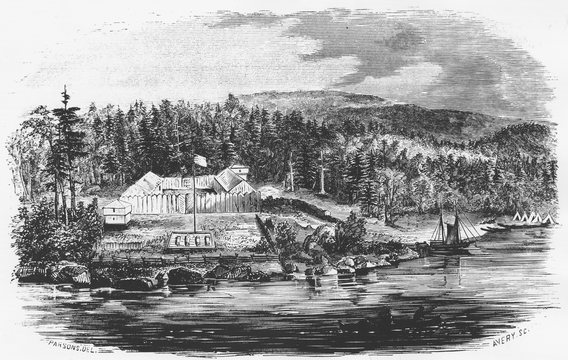

The next day, April 17, Wilson Price Hunt’s group “arrived at the wintering houses, near the Naduet River, and joined the rest of the party.” Neither Bradbury nor Washington Irving said anything about how the men had spent the winter, but Henry Marie Brackenridge offered an opinion when he saw the wooded bluffs and the “log huts” below them a few weeks later: “This is four hundred and fifty miles from the mouth of the Missouri. Here these men must have led the most solitary lives, with no companions but a few hunters and an occasional Indian visitor. Their chief amusement consisted in hunting deer, or traversing the plains.”[2]

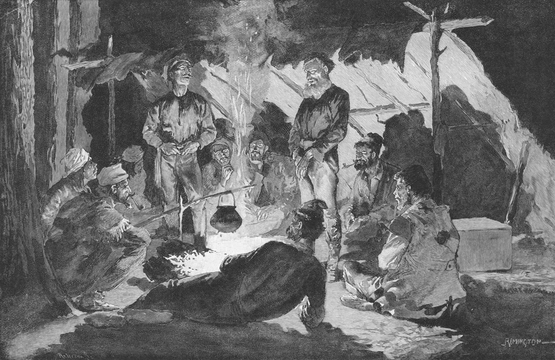

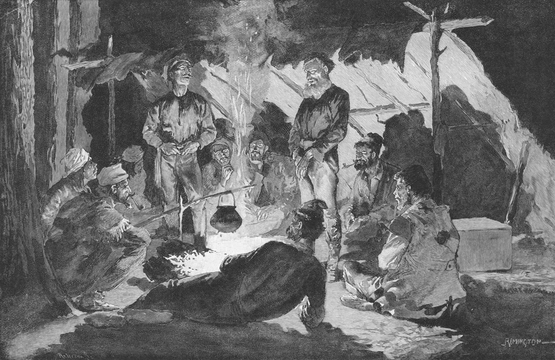

John Reed’s account book revealed one other chief amusement: tobacco. The men bought buffalo robes when the weather turned cold, and as winter wore on they bought everything from shoes, moccasins, needles and thread, deer skins, knives, blankets, and calico, to brass rings, tomahawks, awl blades, kettles, leggings, balls and powder, and hooks and fishing line; but the one constant was tobacco, the most common item mentioned in the log. Second on the list? Tobacco pipes, which went for twenty-five cents apiece. The men frequently bought four at a time.[3] Many a long winter evening was passed around the fire, as the lonely Astorians talked and reminisced, the air thick with the pleasant aroma of tobacco.

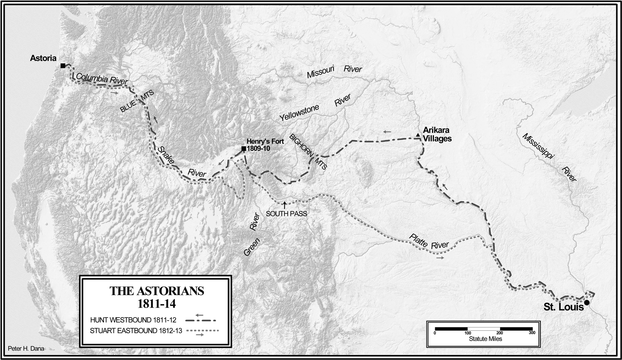

Hunt, Donald McKenzie, Ramsay Crooks, Robert McClellan, Joseph Miller, John Day, Reed, and Pierre Dorion—each of whom was about to leave his indelible mark as one of the “overland Astorians” (a group that would eventually include eighty-six men, one woman, and three children)—were about to travel together for the first time.[4] The experiences of these eight strong—sometimes headstrong—personalities over the next few years would run the gamut, from hopelessness and near starvation to conquests over seemingly immovable obstacles to violent death, and yet little was said by them or by others about their inter-relationships. The affection or scorn they felt for each other remains largely a mystery, although a story of profound friendship and loyalty between two of these men does emerge. What is surprising is that the longtime partners Crooks and McClellan are not the protagonists of that story—their relationship is as inscrutable now as it was two hundred years ago. True, they worked together for more than five years, but neither they nor any of their fellow traders left anything in the historical record to indicate whether they felt mutual admiration for each other (as in the case of Lewis and Clark) or mutual contempt (as in the case of Lewis and Frederick Bates). What we do know is that on their long and difficult trek to the coast and back, they gave no sign of being fast friends and made no apparent effort to stay together through thick and thin. The moving tale of comradeship among the overland Astorians involves not Crooks and McClellan but Crooks and Day.

For three days, Hunt and five dozen men packed food and supplies—and the company store; checked arms and ammunition; inspected boats, oars, masts, and sails; and divided into groups. Nature, too, was on the move, as (now extinct) passenger pigeons “were filling the woods in vast migratory flocks.” Irving, who had apparently seen the magnificent birds during his trip to Missouri in 1832, wrote: “It is almost incredible to describe the prodigious flights of these birds in the western wilderness. They appear absolutely in clouds, and move with astonishing velocity, their wings making a whistling sound as they fly. The rapid evolutions of these flocks, wheeling and shifting suddenly as if with one mind and one impulse . . . are singularly pleasing.”[5]

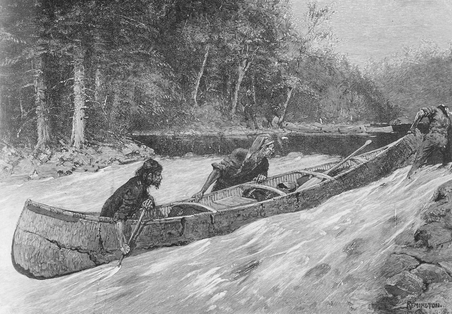

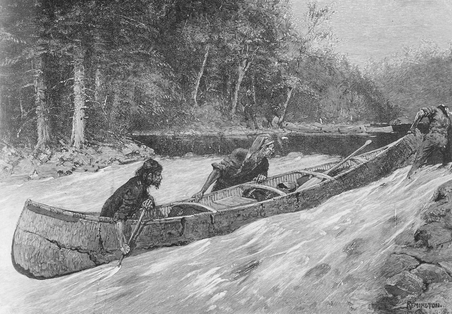

On April 21, wrote Bradbury, “we again embarked in four boats. Our party amounted to nearly sixty persons: forty were Canadian boatmen, such as are employed by the North West Company, and are termed in Canada engagés or voyageurs. Our boats were all furnished with masts and sails, and as the wind blew pretty strong from the south-east, we availed ourselves of it during the greater part of the day.” The winds continued favorable, and they made impressive progress the next three days. Two days after that, however, the wind changed directions, “and blew so strong that [they] were obliged to stop during the whole day.” That night was quite cold, and the next morning, before they “had been long on the river, the sides of the boats and the oars were covered with ice.”[6] That was life on the river.

On April 28, the group “breakfasted on one of the islands formed by La Platte Riviere, the largest river that falls into the Missouri. It empties itself into three channels, except in the time of its annual flood, when the intervening land is overflowed; it is then about a mile in breadth.” Brackenridge added that the Platte River was “regarded by the navigators of the Missouri as a point of as much importance, as the equinoctial line amongst mariners,” or as Irving explained, “The mouth of this river is established as the dividing point between the upper and lower Missouri.” To commemorate this crucial passage, the voyageurs had instituted an initiation ritual. “All those who had not passed it before,” continued Brackenridge, “were required to be shaved, unless they could compromise the matter by a treat. Much merriment was indulged on the occasion.”[7]

Almost four years had passed since John Hoback, Jacob Reznor, and Edward Robinson had come up the river with Manuel Lisa and had crossed to the upper Missouri for the first time, celebrating with “like ceremonials of a rough and waggish nature.”[8] Most of the crew had been shaved that day because only the Lewis and Clark veterans and a few others had already traveled beyond the mouth of the Platte. Nor had Hoback and his two friends returned to the Platte to initiate novice sailors—they had not even been close but had spent their days in present North Dakota and Montana before disappearing with Andrew Henry across the Continental Divide into the Columbia River country.

Though they could not have known, the trio was now the object of a search-and-rescue mission to be undertaken by these newly shaved trappers and boatmen. What was never clear, however, was what Lisa intended to do if he reached the Mandan and Hidatsa villages—or Fort Raymond—and found no trace of Henry. Did he intend to ascend the Bighorn River, or the Gallatin, or the Madison, in an attempt to find Henry, or did he have something else in mind?

Lisa never had to answer those questions. Less than two weeks after the party reached the Platte, wrote Brackenridge, “[W]e found a Mr. Benit, the Missouri Company’s factor at the Mandan village. He was descending in a small batteaux, loaded with peltry, with five men. . . . He . . . informed us that Mr. Henry is at this time over the mountains, in a distressed situation, that he had sent word of his intention to return to the Mandan village in the spring, with his whole party.”[9] How Benit received this “word” from Henry is not clear, but his report was taken seriously, and Henry’s “whole party,” including Hoback, Reznor, and Robinson, was presumed to be on its way to Fort Mandan. The reality turned out to be something quite different.

Not surprisingly, Bradbury and Crooks struck up a friendship. On May 1, Crooks said he planned to leave the next morning on foot, “for the Ottoes, a nation of Indians on the Platte River, who owed him some beaver. From the Ottoes he purposed traveling to the Maha [Omaha] nation, about two hundred miles above us on the Missouri, where he should again meet the boats.” When Bradbury offered to come along, Crooks was delighted, and they “proceeded to cast bullets and make other arrangements for [their] journey. The next morning, however, as they were preparing to depart, a disturbance in the camp caught their attention. “Amongst our hunters were two brothers of the name of Harrington, one of whom, Samuel Harrington, had been hunting on the Missouri for two years, and had joined the party in the autumn: the other, William Harrington, had engaged at St. Louis, in the following March, and accompanied us from thence.” William now informed Hunt that he had enlisted “at the command of his mother, for the purpose of bringing back his brother, and they both declared their intention of abandoning the party immediately.” This was particularly disturbing news because the Osage Indians had warned Hunt that the Sioux intended to oppose his progress up the river. The Canadians were superb boatmen but hardly fighters, making the loss of two expert riflemen simply unacceptable. “Mr. Hunt, although a gentleman of the mildest disposition, was extremely exasperated,” wrote Bradbury, “and when it was found that all arguments and entreaties were unavailing, they were left, as it was then imagined, without a single bullet or a load of powder, four hundred miles at least from any white man’s house, and six hundred and fifty miles from the mouth of the [Missouri] river.”[10]

Both Bradbury and Irving drop the narrative at this point, without saying how the Herrington brothers intended to get back to St. Louis or how they hoped to survive without ammunition. Nor is there any picture of the parting. If Samuel and William were “left” in the literal sense, does that mean they stood on the shore and watched as the boats pulled away? Did they show any signs of shame for having deserted their brothers in arms? Or did they simply start walking downstream through the driftwood, grass, and willows lining the shore while the others made ready to leave?

However things unfolded, Hunt was understandably angry, but he was also, as Bradbury said, a gentleman of mild disposition. He was a man of compassion as well and had shown that at Mackinac, when Baptiste Perrault found himself so worried about his family, deeply regretting the three-year commitment he had made. Hunt released him and helped him find work closer to home, but Perrault had not attempted to deceive anyone and had not placed other men in peril by deserting. Hunt’s leaving the Herringtons without powder or ammunition was severe but still a world away from Lisa’s ordering a deserter shot, something Hunt knew about because he was living and conducting business in St. Louis when George Drouillard and Lisa escaped convictions and prison sentences for Bissonnet’s killing. A lesser man might have threatened to shoot the Herringtons but not Hunt.

Three days later, Brackenridge made this note: “In the evening hailed two men descending in a bark canoe; they had been of Hunt’s party, and had left him on the 2d of May, two days above the Platte, at Boyer’s river.” How the Herringtons obtained their canoe is unknown; nor did Bradbury mention if this information was passed on to anyone in Hunt’s party, but later records indicate that the brothers safely returned to their mother, whose bold actions may have saved her the fate of the dear mother of the two or three Lapensée brothers.[11]

With the matter resolved—at least from the Herringtons’ point of view—Crooks and Bradbury and two Canadians, Gardapie and La Liberte, set out on foot for the Otto village. Over the next nine days—from May 2 to May11—they wandered one stretch of “vast plain” after another; forded a series of streams; met an American trader named Rogers and temporarily escorted his Omaha wife and child (when it became evident that Crooks spoke the Omaha language); built a raft (after discovering that neither Gardapie or La Liberte could swim) to cross the eight-hundred-yard Platte River; heard rumors of an Indian war party; explored an empty Otto village; found—and lost—a horse belonging to Crooks; endured a night of incessant “thunder, lightning, and rain,” the likes of which Bradbury had “seldom witnessed”; visited the grave of a famous Omaha chief named Blackbird; and dined on everything from jerked buffalo and buffalo veal to prairie hens and stalks of plants.[12]

A few days later, Crooks and Bradbury learned that the Otto and Sioux were at war. “It therefore appeared that Mr. Crooks and myself had run a greater risk than we were sensible of at the time,” said Bradbury.[13] But even considering that risk and the real but relatively mild discomforts of hunger and wet and cold experienced by the four men as they hiked the Great Plains, they came through it all with their bodies and spirits unharmed, still eager for more adventure. In six months, Crooks, Gardapie, and La Liberte (Bradbury was spared) would endure a trek of genuine hunger and pain, a trek through an alien landscape that sapped them of any notions of adventure and nearly of their lives. The days of roaming the Otto and Omaha country in spring weather would be pleasant but unrecoverable memory.

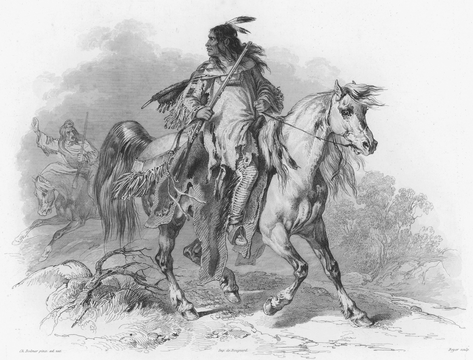

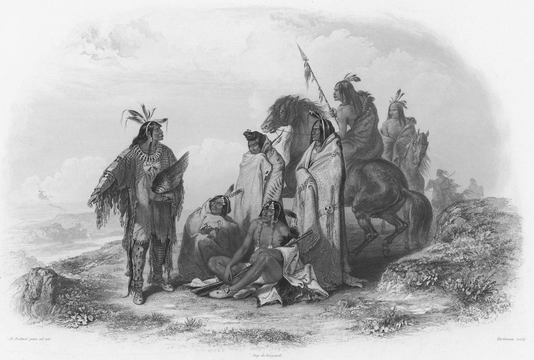

Hunt and the others with the boats, by contrast, had glimpsed a hint of what was to come. On the night of May 7, wrote Washington Irving, with the men encamped on the shore, “there was a wild and fearful yell, and eleven Sioux warriors, stark naked, with tomahawks in their hands, rushed into the camp. They were instantly surrounded and seized, whereupon their leader called out to his followers to desist from any violence, and pretended to be perfectly pacific in his intentions.” Luckily, Dorion was present to interpret, and he advised Hunt that this was a war party that “had been disappointed or defeated in the foray, and in their rage and mortification these eleven warriors had ‘devoted their clothes to the medicine,’ . . . a desperate act of Indian braves when foiled in war, and in dread of scoffs and sneers.” The intent was to “devote themselves to the Great Spirit, and attempt some reckless exploit with which to cover their disgrace.”[14]

Learning this, the majority of Hunt’s party was for shooting the Sioux “on the spot. Mr. Hunt, however, exerted his usual moderation and humanity, and ordered that they should be conveyed across the river in one of the boats, threatening them, however, with certain death, if again caught in any hostile act.” As James Ronda has observed, “It was a wise decision, since killing even a few warriors would have insured violence later.”[15]

Hiring Dorion had also been a wise decision. Not only had he assisted Hunt in avoiding violence, he would be counted on in the coming days because three of Dorion’s Yankton friends soon arrived at the Omaha village and informed him that “several nations of the Sioux”—particularly the Lakota—“were assembling higher up the river, with an intention to oppose our progress.” Vigilance was required, but Hunt had the assurance of knowing that, unlike Lewis and Clark, he would not find himself in a near crisis and conclude “our interpreter do not Speak the language well.”[16]

The five days that Hunt and his men spent with the Omaha were pleasant and productive. James Aird, Crooks’s former supervisor and the man who, wrote William Clark, “received both Capt. Lewis and my Self with every mark of friendship” on September 3, 1806 (three weeks before Lewis and Clark met Crooks), was present and announced he was leaving for St. Louis in a few days. “I therefore availed myself of this opportunity to forward letters,” wrote Bradbury, “and was employed in writing until the 12th [of May] at noon.” Hunt also made the most of the opportunity and wrote a letter to Astor, likely giving a detailed description of the trip up the Missouri. The letter is no longer extant, but Washington Irving, who apparently saw it when he visited Astor in the mid-1830s, wrote: “In his correspondence with Mr. Astor, from this point of his journey, Mr. Hunt gives a sad account of the Indian tribes bordering on the river. They were in continual war with each other,” their wars involving not only the “sackings, burnings, and massacres of towns and villages, but of individual acts of treachery, murder, and cold-blooded cruelty.” No one was safe, not “the lonely hunter, the wandering wayfarer,” or “the squaw cutting wood or gathering corn”—anyone was “liable to be surprised and slaughtered. In this way tribes were either swept away at once, or gradually thinned out, and savage life was surrounded with constant horrors and alarms.”[17]

Bradbury’s encounters with the Omaha were leaving him in a much lighter frame of mind. He was searching for interesting plants when an old Indian galloped toward him. “He came up and shook hands with me, and pointing to the plants I had collected, said, ‘Bon pour manger?’ to which I replied, ‘Ne pas bon.’ He then said, ‘Bon pour medicine?’ I replied ‘Oui.’ He again shook hands and rode away, leaving me somewhat surprised at being addressed in French by an Indian.” But Bradbury was just as surprised when he met two Indians who had seen him in St. Louis and gave “satisfactory proofs of it,” even though he had no memory of them. “The Indians are remarkable for strength of memory in this particular,” explained Bradbury. “They will remember a man whom they have only transiently seen, for a great number of years, and perhaps never during their lives forget him.”[18]

Passing through the village, Bradbury was stopped by a group of Omaha women, who, he said, “invited me very kindly into their lodges, calling me wakendaga, or as it is pronounced, wa-ken-da-ga (physician).” He declined the invitation, saying that he needed to get back to the boats. “They then invited me to stay all night; this also I declined, but suffered them to examine my plants, for all of which they had names.”[19]

Many of the men, however, eagerly accepted the hospitality of the Indian women, a fact that could easily be seen by the entries in Reed’s account book. In the days prior to the arrival at the Omaha village, normal charges followed one after another—tobacco, pipes, strouding, cotton shirts, powder horns, fire steels, knives, and blankets. After the arrival, however, vermilion jumped to the top of the list and was easily the most purchased commodity for the next few days. Produced by grinding minerals into a pigment, vermilion was a powdered dye highly prized by Indian women, who moistened it and used the mixture to paint their faces. (Men also used vermilion as body paint, and both men and women used it to paint objects.) Vermilion was an essential trade item; virtually every group of traders took a good supply up the river, just as Lewis and Clark had done. It could be traded for virtually anything—including horses, food, buffalo robes, or female companionship.[20]

As James Ronda has said, “Omaha women, like their Arikara and Mandan sisters, used their contact with the traders as a means to enhance their own material status.” Such sexual activity among Indian women was hardly looked down on. To the contrary, many Indian men offered their wives or daughters to visiting trappers or explorers, both as a token of good will and also in an effort to partake of the white man’s special powers or medicine. “To modern eyes, the idea of women being given to others may seem like prostitution, but the Indians in question—male and female—did not view it this way. Women fully understood and accepted their roles and were often as eager to engage in sexual relations as the solders [speaking specifically of Lewis and Clark’s men] were.” Not only that, but refusing the advances of the Indian women could be seen as an insult. Lewis and Clark increased the tension between them and the Lakota by declining to accept sexual favors.[21]

By May 14, the run on vermilion had ceased, and Reed got back to normal business. “We embarked early [on the morning of May 15],” wrote Bradbury, “and passed Floyd’s Bluffs, so named from a person of the name of Floyd (one of Messrs. Lewis and Clarke’s party) having been buried there.” (Charles Floyd, a twenty-two-year-old sergeant with Lewis and Clark, had died at this spot, near present Sioux City, Iowa, on August 20, 1804, probably of appendicitis). The winds were favorable, and they made good progress the next few days. Then they were “stopped all day by a strong head wind” and also found “that the river was rising rapidly” from the spring thaw: “It rose during this day more than three feet.” As the river took them west rather than north, they changed their hunting philosophy: “As we were now arriving at the country of our enemies, the Sioux, it was determined that [our hunters] should in a great measure confine themselves to the islands, in their search for game.” Although confined to islands, the hunters still killed three buffalo and two elk on the morning of May 22. “We dined at the commencement of a beautiful prairie,” wrote Bradbury. “Afterwards I went to the bluffs, and proceeded along them till evening. On regaining the bank of the river, I walked down to meet the boats, but did not find them until a considerable time after it was dark.” The boats had not gone as far as Bradbury expected because “they had stopped early in the afternoon, having met with a canoe, in which were two hunters of the names of Jones and Carson.”[22]

Jones and Carson. Twenty days after William and Samuel Herrington had disappeared downstream, leaving Hunt exasperated, their replacements had appeared from upstream, restoring Hunt’s optimism. They were experienced hunters, and Bradbury’s note that they “had been two years near the head of the Missouri” was good evidence they had worked for the Missouri Fur Company and had been present at Three Forks a year earlier with Pierre Menard and Henry, apparently returning with Menard to Fort Mandan. Some time in the few months after that, they had traveled south into present South Dakota and had spent the winter among the Arikara nation. “These men agreed to join the party,” wrote Bradbury, “and were considered as a valuable acquisition; any acquisition of strength being now desirable.”[23]

Jones and Carson were a superior acquisition to the Herringtons because both were Missouri Company men, both hunters with experience fighting Indians, and Carson was also a gunsmith. They had seen their share of peril, it is true, but each of them would see plenty more. Both would reach the Pacific, but they would take different paths and arrive at different times. Both would safely return east, but one would go though the United States and one through Canada. One would be attacked and robbed by Indians and would wander the Rockies destitute and starving and would barely survive; the other would become one of four key founders of the Oregon Trail. Jones and Carson would both live relatively long lives, one dying in 1835 and the other a year later, one dying in Missouri and one in Oregon, one from sickness and the other from a shotgun blast.[24]

Any pleasure Hunt took in the enlistment of Jones and Carson was short-lived. Two days later, actually less than two days, on the morning of May 24, two men arrived at Hunt’s camp near the Ponca village “with a letter to Mr. Hunt from Mr. Lisa.” According to Bradbury, “Mr. Lisa had arrived at the Mahas some days after we left, and had dispatched this man by land. It appeared he had been apprised of the hostile intentions of the Sioux, and the purport of the letter was to prevail on Mr. Hunt to wait for him, that they might, for mutual safety, travel together on that part of the river which those blood thirsty savages frequent.”[25]

The proud Lisa, the man who had ordered Bissonnet shot and had berated him while he was dying, the man who had made certain he reached the Arikara before Nathaniel Pryor and Pierre Chouteau, not caring what happened afterwards, had reduced himself to begging his competitors to wait for him, for “mutual safety” of all things. His exact words are not known—and won’t be until someone discovers the letter itself in an old trunk in the old attic of an old house, or somewhere else. Nor can the immediate reactions of Hunt and Crooks and McClellan be reconstructed because Bradbury suddenly and inexplicably dropped the subject. But Irving hinted that it must have been a scene to behold, especially the wrath of McClellan.

Exactly what Hunt had been thinking about Lisa is not clear. Before Lisa’s messenger arrived, Bradbury had made no mention of Hunt worrying that Lisa might catch him, indicating that Hunt believed he had left early enough in the season not to be concerned. His stays at Fort Osage and the Omaha village where both rather leisurely. But during this same period, Lisa’s men were rowing furiously. “Lisa himself seized the helm, and gave the song, and at the close of every stanza, made the woods ring with his shouts of encouragement. The whole was intermixed, with short and pithy addresses to their fears, their hopes, or their ambition.” At every opportunity, Lisa asked Indians who had seen Hunt when he had passed. By April 26, the group knew they were eighteen days behind, meaning they had gained three days (though they thought they had gained five). Brackenridge was aware, however, that “there existed a reciprocal jealousy and distrust” between the two men, knowing that “Hunt might suppose, that if Lisa overtook him, he would use his superior skill in the navigation of the river, to pass by him, and (from the supposition that Hunt was about to compete with him in the Indian trade) induce the Sioux tribes, through whose territory we had to pass . . . , to stop him, and perhaps pillage him.” That was, of course, exactly what Hunt feared. “Lisa had strong reasons, on the other hand, to suspect that it was Hunt’s intention to prevent us from ascending the river; as well from what has already been mentioned, as from the circumstances of his being accompanied by two traders, Crooks and M’Clelland, who had charged Lisa with being the cause of their detention by the Sioux, two years before; in consequence of which they had experienced considerable losses.” Brackenridge nevertheless hoped that the two groups could unite and “present so formidable an appearance, that the Indians would not think of incommoding [them].”[26]

Lisa pushed his men mercilessly; he had gained several more days by May 4. Warming himself near the fire that night, Brackenridge overheard several of the boatmen talking. “‘It is impossible for us,’ said they, ‘to persevere any longer in this unceasing toil, this over-strained exertion, which wears us down. We are not permitted a moment’s repose; scarcely is time allowed us to eat, or to smoke our pipes. We can stand it no longer, human nature cannot bear it; our bourgeois has no pity on us.’” Trying to ease their minds, Brackenridge reminded them that they were approaching open country, where they could be carried by the wind. “I exhorted them to cease these complaints, and go to work cheerfully,” he wrote, “and with confidence in Lisa, who would carry us through every difficulty. The admonitions had some effect, but were not sufficient to quell entirely the prevailing discontent.”[27]

Two weeks later, Lisa’s party discovered they were only six or seven days behind Hunt. “Our men feel new animation on this unexpected turn of fortune,” said Brackenridge. On May 19 they launched their boats at first sunlight, “with the hope of reaching the Maha village in the course of the day. Here we entertained sanguine hopes of overtaking the party of Hunt, and with these hopes the spirits of our men, almost sinking under extreme labor, were kept up; their rising discontents, the consequences of which I feared almost as much as the enmity of the Indians, were by the same means kept down.” Around noon, the Omaha village came in sight. “We anxiously looked towards the place, and endeavoured to descry the party of Hunt; but as we drew near we found, alas! they were not there.”[28]

Hunt, they were told, had left four days earlier. As if that weren’t bad enough, the Sioux had learned “that a number of traders are ascending the river, in consequence of which, instead of going into the plains as is usual at this season of the year, they are resolved to remain on the river, with a determination to let no boats pass; that they had lately murdered several white traders, and were exceedingly exasperated at the conduct of Crooks and M’Clelland [in 1809].” So, if Crooks and McClellan were correct in concluding that Lisa had been the cause of their troubles with the Sioux, Lisa’s treachery had now come full circle to haunt him. Hardly one to express—or even contemplate—such irony, Lisa resolved to leave the Omaha village immediately, breaking etiquette by not even stopping to pay respects to a prominent chief by the name of Big Elk (as all traders were expected to do). Lisa also decided to “despatch a messenger by land, who might overtake [Hunt] at the Poncas village, about two hundred miles further by water and about three days journey by land. For this purpose a half Indian was hired [as a guide], and set off immediately in company with Toussaint Charbonneau. As Lavender has explained, “the Missouri twisted prodigiously. By short-cutting its bends (as Crooks and Bradbury had done after their side jaunt to the Oto village), good walkers could overtake Hunt before he reached Sioux.”[29]

Lisa had chosen Sacagawea’s husband, Lewis and Clark’s interpreter, as his emissary, but Bradbury had no idea who Charbonneau was. Hunt and Charbonneau communicated in French, with Hunt giving his assurances that his group would remain at the Ponca village and wait for Lisa. Charbonneau and his Indian guide immediately obtained a canoe and set off downstream to deliver the good news to Lisa. (Whether Charbonneau and Dorion interacted is not known.) “It was judged expedient to trade with the Indians for some jerked buffalo meat, and more than 1000 lbs. was obtained for as much tobacco as cost two dollars,” wrote Bradbury. Hunt wanted the meat to save travel time. Urged on by Crooks and by McClellan—who had “renewed his open threat of shooting [Lisa] the moment he met him on Indian land”—Hunt had lied to Charbonneau, hoping his promise would encourage Lisa to cut back on his hectic pace. He had no intention of waiting for Lisa but wanted to get upriver as fast as possible, preferring an encounter with the Sioux, even with his limited force of riflemen, to any involvement with Lisa, who was liable to sabotage the Astorian enterprise at the first opportunity. At noon the expedition set off in great haste. The real race was now on.[30]

Bad news followed bad news. Early the next morning, wrote Bradbury, it was discovered that “two men who had engaged at the Mahas, and had received equipments to a considerable value, had deserted in the night. As it was known that one of them could not swim, and we had passed a large creek about a league below, our party went in pursuit of them, but without success.”[31] Once again, however, two deserters would be replaced through a quirk of circumstance.

The next morning, May 26, Hunt’s men were eating breakfast on a beautiful stretch of the Missouri when someone spotted two canoes descending on the opposite side of the river. “In one,” wrote Bradbury, “by the help of our glasses [telescopes], we ascertained there were two white men, and in the other only one. A gun was discharged, when they discovered us, and crossed over. We found them to be three men from Kentucky.” These three, said Bradbury, “had been several years hunting on and beyond the Rocky Mountains, until they imagined they were tired of the hunting life; and having families and good plantations in Kentucky, were returning to them; but on seeing us, families, plantations, and all vanished; they agreed to join, and turned their canoes adrift.”[32]

More than four years after leaving St. Louis and one year after leaving Three Forks, Hoback, Reznor, and Robinson had made it back, almost back, that is. From their position in present southeast South Dakota they were close—three weeks or less from St. Louis, where they could board boats bound for their Kentucky homes via the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. But, as Bradbury said, all vanished with the prospect of working for John Jacob Astor. Nor was their original contract with Lisa the issue. They had fulfilled their three-year agreement by the time Menard had left Three Forks in the spring of 1810 and could have gone home then.

The scene was a virtual reenactment of what had happened four years earlier, when Lisa’s group, including Hoback and his two friends, had seen John Colter canoeing his way down the Missouri, two or three weeks from home and family. When offered a contract, Colter had not hesitated, turning his back on home sweet home for the siren song of the Rocky Mountains. Now, the trio of trappers had followed in Colter’s footsteps, even though they had been present at Three Forks when Colter had expressed his deep regret at returning west and told of his vow to his Maker.[33]

The pronouncement that all three men had families and plantations in Kentucky, however, was not the whole truth and nothing but the truth. While the sketchy historical record indicates that was true for Hoback and Robinson, Reznor had taken a different path, apparently leaving his family in 1797—the last year his name shows up in the Kentucky records. According to Reznor family tradition, he had gone “off west to the mountains with a party of trappers and hunters and was never heard from again.” He left at least three children—Solomon, seven; William, one; and Nancy, age unknown. Early in 1804, his wife, Sarah, remarried, with the marriage record calling her “the widow of Jacob Reizoner.” He had apparently been gone long enough to be declared dead, although an official declaration has not been found. Reznor’s missing decade remains a mystery—we don’t know where he wandered or if he learned that his parents had died, his mother in about 1805 and his father in 1807. He may have settled in present Illinois, for a Jacob Reznor turns up in the Indiana Territory census in 1807.[34] But where he was headed before meeting the Astorians is hazy, like his recent past.

There is little doubt, however, that before being hailed from the shore, Hoback and Robinson had every expectation of seeing their families soon, every hope of walking unannounced down a familiar path and watching as someone in the old house recognized them and came running; savoring the embrace of a wife, feeling young and green again at the prospect of spending a night together for the first time in fifteen hundred days and counting; seeing sons, daughters, or even grandchildren transformed from children to adolescents, or from adolescents to young men and women; and enjoying a pipe stuffed with fresh tobacco in a real house, with a fire in the old hearth, and a faithful dog sitting close by.

All that vanished, perhaps as soon as the scene along the riverbank came into focus. “The sight of a powerful party of traders, trappers, hunters, and voyageurs, well armed and equipped, furnished at all points, in high health and spirits, and banqueting lustily on the green margin of the river,” wrote Irving, “was a spectacle equally stimulating to these veteran backwoodsmen with the glorious array of a campaigning army to an old soldier; but, when they learned the grand scope and extent of the enterprise in hand it was irresistible.”[35]

The arrival of the three wanderers gave Jones and Carson a chance to renew old friendships, to reflect on the attacks at Three Forks, to ask about the men who had gone south with Henry. One name likely to come up was that of Pelton. Sometime in the last year—although the exact time and location were apparently never recorded—the jovial Yankee had lost his mind and disappeared into the dreary wilderness, gone forever, or so it seemed.

For Hoback, Reznor, and Robinson, there were at least two other familiar faces among the Astorians—Crooks and McClellan, who had both met Lisa’s contingent in the spring of 1807. But most of the other men were strangers, French speakers, Canadians, not Kaintucks. And this group took a particular interest in the old man.

“Robinson was sixty-six years of age,” wrote Bradbury, “and was one of the first settlers in Kentucky. He had been in several engagements with the Indians there, who really made it to the first settlers, what its name imports, ‘The Bloody Ground.’ In one of these engagements he was scalped, and has since been obliged to wear a handkerchief on his head to protect the part.”[36]

If Robinson offered further details, Bradbury did not record them, but the sexagenarian had been present at the siege of Fort Henry in September of 1777, at the future site of Wheeling, West Virginia. Before attacking the fort itself, three or four hundred Wyandot, Shawnee, and Mingo Indians—armed and encouraged by the British—had gathered in the woods, staging a series of ambushes on small groups of soldiers who ventured from the safety of the garrison. Robinson could have been scalped, or “wounded,” in one of these encounters, when the Revolutionary War was two years old and Robinson thirty-two. “Where scalping only is inflicted, it puts the person to excruciating pain, though death does not always ensure,” a contemporary of Robinson’s had written in 1791. “There are instances of persons of both sexes, now living in America . . . who, after having been scalped, by wearing a plate of silver or tin on the crown of the head, to keep it from cold, enjoy a good state of health, and are seldom afflicted with pain.”[37]

In the autumn of 1810, Robinson had found himself at another Fort Henry, this one quite different from the one he had known thirty-three years earlier. The first had been constructed near the Ohio River by four hundred men, bordered by a bluff and a ravine, complete with blockhouses, a palisade of eight-to-ten-foot pickets, cabins, horse corrals, and storehouses. The second was hardly worthy of being called a fort, nothing more than a collection of huts thrown together on a stretch of the Snake River plain overgrown with sagebrush. This time Robinson was on the Pacific side of the Continental Divide, near a river known ever since as Henry’s Fork. Leaving the Wyandot and Mingo far behind him, Robinson’s most recent scrapes with Indians had involved the Blackfoot, who had killed several of his fellow trappers, and the Crow, who had stolen many of the group’s horses as they crossed the mountains. And although Brackenridge would later write that “Mr. Henry wintered in a delightful country, on a beautiful navigable stream,”[38] that was hardly the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

“The sufferings of Mr. Henry and his party on the Columbia, and in crossing the mountains, have been seldom exceeded,” the Louisiana Gazette reported. “A great part of his time he subsisted principally on roots, and having lost his clothes, like another Crusoe, dressed himself from head to foot in skins.” Thomas Biddle offered a similar report in 1819, writing that Henry’s group “wintered in 1810–1811 on the waters of the Columbia. At this position they suffered much for provisions, and were compelled to live for some months entirely upon their horses.” He added that the party became “dispirited, and began to separate: some returned into the United States by way of the Missouri, and others made their way south, into the Spanish settlements, by the way of the Rio del Norte.”[39]

Hoback, Reznor, and Robinson had been among those returning east by way of the Missouri—actually branches of the Missouri. As far as is known, they had no compasses, sextants, maps, or anything of the sort, and arrived at Hunt’s camp without any written record of their trek. Still, they were about to have a dramatic impact on westward expansion.

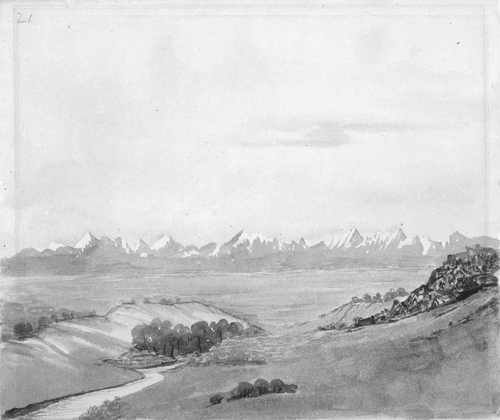

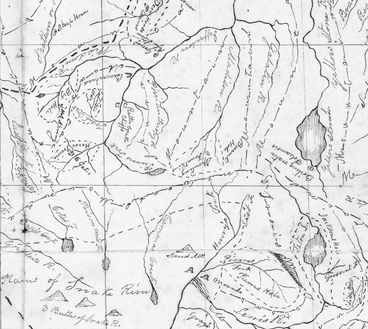

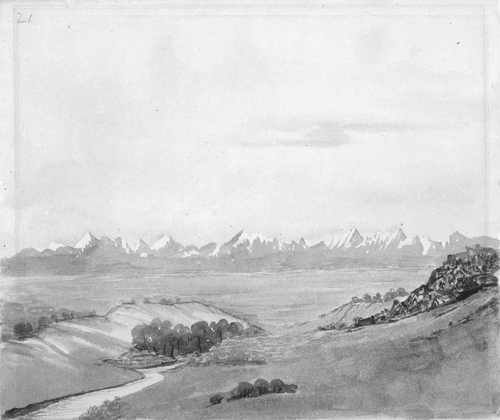

“As we had now in our party five men who had traversed the Rocky Mountains in various directions,” wrote Bradbury, “the best possible route in which to cross them became a subject of anxious enquiry. They all agreed that the route followed by Lewis and Clarke was very far from being the best, and that to the southward, where the head waters of the Platte and Roche Jaune [Yellowstone] rivers rise, they had discovered a route much less difficult.” Hunt, who had originally planned to follow the Missouri River across present Montana, as Lewis and Clark had done in 1805, now rejected his second choice, “which had been to ascend the Missouri to the Roche Jaune river, one thousand eight hundred and eighty miles from the mouth, and at that place to commence his journey by land.” The more southerly course, noted Irving, would allow Hunt to “pass through a country abounding with game, where he would have a better chance of procuring a constant supply of provisions than by the other route, and would run less risk of molestation from the Blackfeet.” Taking the recommended path also meant that Hunt should “abandon the river at the Arickara town, at which he would arrive in the course of a few days. As the Indians at that town possessed horses in abundance, he might purchase a sufficient number of them for his great journey overland, which would commence at that place.” After consulting with McKenzie, Crooks, McClellan, and Miller, “Hunt came to the determination to follow the route thus pointed out, to which the hunters [Hoback, Reznor, and Robinson] engaged to pilot him.”[40]

None of Lisa’s former employees could have been surprised at the bad blood between him and Hunt or that Hunt wanted to keep his distance. For the moment, however, there were other concerns. The weather had turned pleasant and should have been perfect for rowing, but there were so many carcasses of drowned buffalo lining the shore of the twisting river that the stench was overwhelming. The men—and Marie and her boys—endured the best they could, and a favorable wind got them to a straight, clear stretch of water. They made thirty miles on May 30 but the next morning saw something more alarming than dead bison: “We discovered two Indians on a bluff on the north-east side of the river,” wrote Bradbury. “They frequently harangued us in a loud tone of voice. After we had breakfasted, Mr. Hunt crossed the river to speak with them, and took with him Dorion, the interpreter.”[41]

When Hunt and Dorion returned, they informed the group “that these Indians belonged to the Sioux nations; that three tribes were encamped about a league from us, and had two hundred and eighty lodges.” Any doubts about hiring Dorion were instantly dispelled, for the nearby Indians included both Yankton and Lakota Sioux. Dorion had lived among the Yankton, spoke fluent Sioux, and was the best man to negotiate. Even so, the news was not good: “The Indians informed Mr. Hunt that they had been waiting for us eleven days, with a decided intention of opposing our progress, as they would suffer no one to trade with the Ricaras, Mandans, and Minaterees [Hidatsa], being at war with those nations.” Since it was normal to estimate two warriors to a lodge, Hunt and his men faced the prospect of facing almost six hundred warriors intent on blocking the way. Not only that, but “it had also been stated by the Indians that they were in daily expectations of being joined two other [Lakota] tribes.”[42]

Hunt’s group proceeded cautiously upstream, but a large island blocked their view of the opposite shore for almost thirty minutes. “On reaching the upper point we had a view of the bluffs, and saw the Indians pouring down in great numbers, some on horseback, and others on foot. They soon took possession of a point a little above us, and ranged themselves along the bank of the river.” Watching the Indians through their telescopes, Hunt and the other partners “could perceive that [the Sioux] were all armed and painted for war. Their arms consisted chiefly of bows and arrows, but a few had short carbines: they were also provided with round shields. We had an ample sufficiency of arms for the whole party, which now consisted of sixty men; and besides our small arms, we had a swivel and two howitzers.”[43]

The choice was simple: either fight or retreat down river, effectually abandoning Astor’s enterprise. “The former was immediately decided on,” and the group landed on the shore opposite the main body of warriors. Every man checked his rifle and ammunition. Next the cannon and the howitzers were filled with powder and fired, making Hunt’s intentions clear. “They were then heavily loaded, and with as many bullets as it was supposed they would bear, after which we crossed the river. When we arrived within about one hundred yards of them, the boats were stationed, and all seized their arms.” Apparently stunned that their bluff had been called, “the Indians now seemed to be in confusion, and when we rose up to fire, they spread their buffaloe robes before them, and moved them from side to side.” At least one of Hunt’s men understood what this meant: “Our interpreter called out, and desired us not to fire, as the action indicated, on their part, a wish to avoid an engagement, and to come to a parley.”[44]

Hunt instantly agreed and requested that McKenzie, Crooks, McClellan, and Miller—along with the indispensable Dorion—join him in smoking the calumet with the Sioux chiefs. Bradbury accompanied the partners while the men in the boats stood by their arms. “We found the chiefs sitting where they had first placed themselves, as motionless as statues; and without any hesitation or delay, we sat down on the sand in such a manner as to complete circle. When we were all seated, the pipe was brought by an Indian, who seemed to act as priest on this occasion: he stepped within the circle, and lighted the pipe.” The pipe was at least six feet long and was elaborately decorated with tufts of horse hair that had been dyed red. The priest lifted it toward the sun, then pointed it in different directions. “He then handed it to the great chief, who smoked a few whiffs, and taking the head of the pipe in his hand, commenced by applying the other end to the lips of Mr. Hunt, and afterwards did the same to every one in the circle. When this ceremony was ended, Mr. Hunt rose, and made a speech in French, which was translated as he proceeded into the Sioux language, by Dorion.” Hunt made it clear that his purpose was not to trade with enemies of the Sioux but to go his brothers who “had gone to the great salt lake in the west, whom [he] had not seen for eleven moons.” He and his men would rather die than not go to their brothers, and they would kill anyone opposing them. But, Hunt adeptly added, to show his good will to the Sioux, he had brought gifts. “About fifteen carrottes of tobacco, and as many bags of corn, were now brought from the boat, and laid in a heap near the great chief, who then rose and began a speech, which was repeated in French by Dorion.” Not only did the chief accept the gift, he advised Hunt to camp on the opposite side of the river to avoid trouble from overzealous Indians. “When the speech was ended, we all rose, shook hands, and returned to the boats.”[45]

Over the next few days, Hunt successfully negotiated with two hostile groups of Indians who were enemies of each other. The first was the same group of Sioux guilty of “plundering and otherwise maltreating” Crooks and McClellan the previous two years. The second was a war party, three hundred men strong, of Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa warriors intent on attacking the Sioux. On meeting Hunt, however, they decided to accompany him to the Arikara villages in hopes of obtaining more arms and ammunition. On the morning of June 3, one of the chiefs overtook Hunt on horseback and “said that his people were not satisfied to go home without some proof of their having seen the white men.” Hunt agreed, and the chief was “much pleased” at receiving a cask of powder, a bag of balls, and three dozen knives. Just as this was happening, an Indian ran up and informed Hunt that a boat was coming up the river. We immediately concluded that it was the boat belonging to Manuel Lisa, and after proceeding five or six miles, we waited for it.”[46]

Lisa’s boat arrived, and Brackenridge came over to greet Bradbury. “It was with real pleasure I took my friend Bradbury by the hand,” noted Brackenridge, adding this cryptic aside: “I had reason to believe our meeting was much more cordial than that of the two commanders.” Nor did Bradbury offer any information on what happened between Hunt and Lisa, merely reporting that he took advantage of the increased security to take a walk along the bluffs. “On my return to the boats,” he wrote, “I found that some of the leaders of the party were extremely apprehensive of treachery on the part of Mr. Lisa, who being now no longer in fear of the Sioux, they suspected had an intention of quitting us shortly, and of doing us an injury with the Aricaras. Independent of this feeling, it had required all the address of Mr. Hunt to prevent Mr. McClellan or Mr. Crooks from calling him to account for instigating the Sioux to treat them ill the preceding year.” Brackenridge hardly described McClellan’s attitude as wanting to call Lisa “to account”—instead reporting that McClellan had “pledged his honor” to shoot Lisa on sight “if ever he fell in with [him], in the Indian country” and that it was only through Hunt that McClellen “was induced not to put his threat in execution.”[47]

Bloodshed was avoided—for the moment—but Hunt and the other partners were convinced that Lisa, although giving the appearance of being friendly, was determined to sabotage Astor’s enterprise and would do so at the first opportunity. Moreover, Lisa had twenty expert oars on his keelboat, and—as shown by the way he had caught Hunt—could get away cleanly upstream if needed. “It was determined,” wrote Bradbury, “to watch [Lisa’s] conduct narrowly.”[48]

An uneasy truce persisted for two days, but on June 5, after he and Brackenridge had been out hunting and exploring, Bradbury wrote that “a circumstance happened that for some time threatened to produce tragical consequences. We learned that, during our absence, Mr. Lisa had invited Dorion, our interpreter, to his boat, where he had given him some whiskey, and took that opportunity of avowing his intention to take him away from Mr. Hunt, in consequence of a debt due by Dorion to the Missouri Fur Company, for whom Lisa was agent.” This strategy promptly backfired. As Irving wrote, “The mention of this debt always stirred up the gall of Pierre Dorion, bringing with it the remembrance of the whiskey extortion. A violent quarrel arose between him and Lisa, and [Dorion] left the boat in high dudgeon,” returning to his own camp to tell Hunt what had happened. He had hardly reached his own tent when Bradbury and Lisa arrived by pure coincidence at the same time, Lisa on the pretext of borrowing a cordeau, or towing line from Hunt. Hearing Lisa, the rabid Dorion “instantly sprang out of his tent, and struck him. Lisa flew into the most violent rage, crying out, “O mon Dieu! ou est mon couteau!”—“O my God! Where is my knife!” Then he ran toward his own camp.[49]

Picking up the narrative, Brackenridge related what happened when he set foot in Lisa’s camp: “I found Mr. Lisa furious with rage, buckling on his knife, and preparing to return: finding that I could not dissuade him, I resolved to accompany him.” Lisa’s honor had been offended, and he was primed for a duel, but why he went out to face Dorion with a knife rather than a pistol is not clear. Predictably, Dorion armed himself with a pair of pistols, “and took his ground, the party ranging themselves in order to witness the event.”[50]

Neither Bradbury nor Brackenridge mentioned whether Marie was watching from the sidelines, but both of them were determined to stop the affair of honor. Dorion had a pistol in each hand, and Brackenridge stood between him and Lisa. “As Dorion had disclosed what had passed in Lisa’s boat,” wrote Bradbury, “Messrs. Crooks and M’Clellan were each very eager to take up the quarrel, but were restrained by Mr. Hunt.”[51] Seconds later, however, Lisa cast an insult in Hunt’s direction, and the man who had kept a tight rein on his passions through more than a year of quandaries and frustrations as the leader of the overland Astorians finally hit his limit. He announced that the mater would be settled between him and Lisa and told the Spaniard to go fetch his pistols.

“I followed Lisa to his boat, accompanied by Mr. Brackenridge” said Bradbury, “and we with difficulty prevented a meeting, which, in the present temper of the parties, would certainly have been bloody one.”[52] Bradbury and Brackenridge had great powers of persuasion because Lisa was not the kind of man to back down from a challenge. He stayed in his camp, however, escaping the wrath of Dorion, Crooks, McClellan, and Hunt like he had that of Rose, Cheek, James, and any number of others.

“Having obtained, in some measure, the confidence of Mr. Hunt, and the gentlemen who were with him” wrote Brackenridge, “and Mr. Bradbury that of Mr. Lisa, we mutually agreed to use all the arts of mediation in our power, and if possible, prevent any thing serious.” The mediation worked, and the boats proceeded up the river one after another but maintained separate camps. “Continued under way as usual,” Brackenridge wrote two days later. “All kind of intercourse between the leaders has ceased.”[53]

By June 11, however, the Astorians and Missouri Fur Company men were approaching the Arikara villages and had to communicate with each other. These were the same Indians who in 1807 had meted out such harsh treatment to Charles Courtin, who had attacked Pryor and Chouteau, killing four men and wounding several others. “This evening I went to the camp of Mr. Hunt to make arrangements as to the manner of arriving at the village, and of receiving the chiefs,” wrote Brackenridge. “This is the first time our leaders have had any intercourse directly or indirectly since the quarrel. Mr Lisa appeared to be suspected; they supposed it to be his intention to take advantage of his influence with the Arikara nation, and do their party some injury in revenge. I pledged myself that this should not be the case.”[54]

The next day, two Arikara chiefs came onboard Lisa’s boat, accompanied by an interpreter, none other than Joseph Gravelines, who had assisted Lewis and Clark in 1804 and had attempted to assist Courtin in 1807. “The leaders of the party of Hunt were still suspicious that Lisa intended to betray them,” noted Brackenridge. “M’Clelland declared that he would shoot him the moment he discovered any thing like it.”[55] But Lisa did nothing to provoke McClellan or anyone else. When the chiefs finally assembled later in the day with the traders, a pipe was sent around, and one chief declared he was happy to see his friends in his village.

Next came one of the most remarkable speeches known to have passed from Lisa’s lips. “Lisa in reply to this, after the usual common-place, observed that he was come to trade amongst them and the Mandans, but that these persons, (pointing to Hunt and his comrades,) were going on a long journey to the great Salt lake, to the west, and he hoped would meet with favourable treatment; and that any injury offered them, he would consider as done to himself; that although distinct parties, yet as to the safety of either, they were but one.” This said Brackenridge, “at once removed all suspicion from the minds of the others.”[56] Whether that was true or not, the dispute with Lisa was put to rest, and apparently not even McClellan made any more threats. On June 18, Lisa agreed to buy Hunt’s boats, offering horses from Fort Mandan as part of the deal. At the same time, Hunt attempted, with limited success, to purchase horses from the Arikara.

About this same time, Hunt added one more recruit to his roster, a man well known to Hoback, Reznor, and Robinson—and to Lisa: Edward Rose. After joining Lisa’s 1809 expedition, he had apparently gone with Henry to Fort Raymond and Three Forks, but had vanished at some point, probably living among the Indians until reappearing—a pattern typical of his entire career. As Irving wrote, he had arrived at an opportune time: “The dangers to be apprehended from the Crow Indians had not been overrated by the camp gossips.” The Crow, “through whose mountain haunts the party would have to pass, were noted for daring and excursive habits, and great dexterity in horse stealing. Mr. Hunt, therefore, considered himself fortunate in having met with a man who might be of great use to him in any intercourse he might have with the tribe.” Rose, of course, had lived among the Crow, becoming a feared warrior and chief among them (by his own account) and was perfectly at home with their language and culture. And although Irving consistently described “the Five Scalps” (Rose’s Crow name) in negative terms, the fur trade historian Hiram Martin Chittenden properly pointed out “that everything definite that is known about him is entirely to his credit.”[57]

Rose’s purchases from Reed’s company store were likely typical of the other men. He bought powder, balls, scalping knives, a coffee kettle, pipes, tobacco, a shirt, and a bridle for the journey; to enjoy female companionship during his stay at the Arikara villages he bought blue beads, a yard of blue flannel and another of green cloth. “Our common boatmen soon became objects of contempt, from their loose habits and ungovernable propensities” wrote Brackenridge. “To these people, it seemed to me that the greater part of their females, during our stay, had become mere articles of traffic; after dusk, the plain behind our tents was crowded with these wretches, and shocking to relate, fathers brought their daughters, husbands their wives, brothers their sisters, to be offered for sale at this market of indecency and shame.” The Indian women, it seemed, had been seized by an “inordinate passion . . . for our merchandize,” and the “silly boatmen . . . in a short time disposed of almost every article which they possessed, even their blankets, and shirts. One of them actually returned to the camp, one morning entirely naked, having disposed of his last shirt—this might truly be called la derniere chemisse de l’amour.”[58]

But Brackenridge also experienced peaceful times among the Arikara. “In the evening, about sundown,” he wrote, “the women cease from their labors, and collect in little knots, and amuse themselves with a game something like jack-stones: five pebbles are tossed up in a small basket, with which they endeavor to catch them again as they fall.”[59] Whether the Indian women present with Hunt and Lisa—Marie Dorion and Sacagawea—joined in the game is not known. Nor did Bradbury or Brackenridge say a single word about them. Their French Canadian interpreter husbands, however, had much in common and no reason to quarrel, so it is possible that during the peaceful week from June 12 (when Lisa argued for Hunt’s safe passage before the Arikara chiefs) to June 19 (when Lisa and no doubt Charbonneau and his family departed for the Mandan villages) Marie and Sacagawea had a chance to meet, even converse through their husbands, for they shared no common language. Playing with Marie’s boys would have made Sacagawea lonely for her own son, now six years old and living under William Clark’s care in St. Louis, the son she would never see again.

One day before Lisa left, Crooks, Bradbury, and others headed overland for the Mandan villages to collect the horses promised by Lisa. They were guided by Benjamin Jones. They reached Fort Mandan on June 22 and obtained approximately fifty horses. Crooks and his companions began driving the horses south on June 27, taking pains to keep their plans secret (and the horses safe) from local Indians. Bradbury waited several days, then returned by boat with Lisa to the Arikara towns. “I had the pleasure of meeting my former companions,” he wrote on July 7, “and was rejoiced to find that Mr. Crooks arrived safely with the horses, and that Mr. Hunt had now obtained nearly eighty in all. Soon after my arrival, Mr. Hunt informed me of his intention to depart from the Aricaras shortly.” Ten days later, on July 17, Bradbury, now traveling with Brackenridge, added a benediction to his memorable time with the Astorians: “I took leave of my worthy friends, Messrs. Hunt, Crooks, and M’Kenzie, whose kindness and attention to me had been such to render the parting painful; and I am happy in having this opportunity of testifying my gratitude and respect for them.” Waving goodbye, Bradbury boarded one of Lisa’s boats, and as the boat swung out into the Missouri, “Mr. Hunt caused the men to draw up in a line, and give three cheers, which we returned; and we soon lost sight of them.”[60]

1. Bradbury, Travels, 68, italics in original.

2. Ibid.; Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 70. Brackenridge also offered a brief but insightful look at two of Lisa’s chief rivals: “M’Cleland was one of Wayne’s runners, and is celebrated for his courage and uncommon activity. The stories related of his personal prowess, border on the marvelous. Crooks is a young Scotchman, of an enterprising character, who came to this country from the trading associations in Canada” (Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 70–71).

3. “Among the Astor papers, deposited at Baker Library, Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration, are two journals of the overland expedition to Astoria, containing accounts of the debits of persons connected with the expedition for articles obtained from its commissary and credits due them for wages, skins, etc. The first of these books begins at La Chine, July 6, 1810, and the second and last ends at Astoria, February 20, 1812. Here we can find data in regard to the clothing, equipment, ornaments, luxuries and amusements of the Canadian voyageurs and the American hunter and trapper, together with the prices charged them for the various articles included in the foregoing categories and the wages which were largely, and often more than totally, swallowed up in their purchases” (Porter, “Roll of Overland Astorians,” 103).

4. The total number of overland Astorians (not including Marie Dorion or her children) is eighty-six, but that includes several who served for brief periods of time. From July of 1810 to February of 1812, there were regular deserters and regular recruits. (Porter, “Roll of Overland Astorians.”)

5. Irving, Astoria, 154.

6. Bradbury, Travels, 70, 71, italics in original.

7. Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 79; Irving, Astoria, 156.

8. Irving, Astoria, 156.

9. Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 98–99.

10. Bradbury, Travels, 74–75, bracketed insertion added.

11. Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 73–74. If Samuel Herrington had been hunting on the Missouri for two years (as Bradbury claims), he quite possibly went up the river in 1809, with Thomas James and scores of others. The first mention of him in John Reed’s account book came on December 31, 1810, at the winter camp at the mouth of the Nodaway River (meaning that his family could have learned of his status from someone who returned to St. Louis with Hunt in January of 1811). William enlisted in St. Louis in March of 1811. The 1830 Federal Census lists a Samuel Herrington living in Merrimac, Jefferson County, Missouri, between forty and forty-nine years old, with a wife between thirty and thirty-nine, and five children under the age of twenty. The 1850 Federal Census for the same town and county lists a William Herrington, sixty-two years old, with sons twenty and twelve years old.

12. Bradbury, Travels, 75–86. Bradbury wrote that Blackbird “ruled over the Mahas with a sway the most despotic. He had managed in such a manner as to inspire them with the belief that he was possessed of supernatural powers: in council no chief durst oppose him—in war it was death to disobey. . . . He died about the time that Louisana was added to the United States; having previously made choice of a cave for his sepulchre, on the top of a hill near the Missouri, about eighteen miles below the Maha village. By his order his body was placed on the back of his favorite horse, which was driven in the cave, the mouth of which was then closed up with stones. A large heap was afterwards raised on the summit of the hill” (Bradbury, Travels, 85n47).

13. Ibid., 92.

14. Irving, Astoria, 158.

15. Ibid., 158–59; Ronda, Empire, 147.

16. Bradbury, Travels, 90–91; Clark’s journal entry, September 25, 1804, Moulton, Journals, 3:111.

17. Clark’s journal entry, September 3, 1806, Moulton, Journals, 8:346; Irving, Astoria, 160.

18. Bradbury, Travels, 88–89, 89n51, italics in original.

19. Ibid., 89.

20. Background on vermilion from Tubbs, Companion, 299, which further points out that “Captain Lewis used vermilion . . . to convince three wary Shoshone women he meant no harm on August 13, 1805: ‘I now painted their tawny cheeks with vermilion which with this nation is emblematic of peace,’ information he had obtained from Sacagawea.”

21. Ronda, Empire, 148; Woodger and Toropov, Encyclopedia, 316, bracketed insertion added.

22. Bradbury, Travels, 91, 92, 93. Concerning Floyd’s death, William Clark wrote: “Passed two Islands on the S. S. And at first Bluff on the S S. Serj.’ Floyd Died with a great deel of Composure, before his death he Said to me, ‘I am going away” [‘]I want you to write me a letter’—We buried him on the top of the bluff ½ Miles below a Small river to which we Gave his name, he was buried with the Honors of War much lamented.” (Clark’s journal entry, August 20, 1804, Moulton, Journals, 2:495.)

23. Bradbury, Travels, 93.

24. Carson is thought by some to have been with Lewis and Clark during the first leg of their journey, but the evidence is quite tentative. See the Biographical Directory for more information on both Jones and Carson.

25. Bradbury, Travels, 96–97

26. Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 58, 59–60.

27. Ibid., 72–73.

28. Ibid., 85, 89.

29. Ibid., 89–90, 90–91, bracketed insertions added; Lavender, Fist in the Wilderness, 154.

30. Bradbury, Travels, 97; Irving, Astoria, 173. Charbonneau and his companion arrived at Lisa’s camp at dawn on May 26. Brackenridge wrote: “They bring us the pleasing information, that Hunt, in consequence of our request, has agreed to wait for us, at the Poncas village” (Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 102).

31. Bradbury, Travels, 97. The two deserters were Joseph La Gemonier and Louis Rivard. (Porter, “Overland Astorians,” 108, 111).

32. Bradbury, Travels, 98, italics in original.

33. Bradbury does not say whether Hoback, Reznor, and Robinson were informed that Hunt and other members of the party had talked with Colter ten weeks earlier.

34. Anderson, Reasoner Story, 52–56; Randolph County, Indiana, Census, 1807.

35. Irving, Astoria, 176–77.

36. Ibid., 98.

37. John Long, Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and Trader, cited in Irving, Astoria, 176n5. One history of Wheeling, West Virginia, offers this description of the fighting at Fort Henry: “After the successful ambuscade the entire body of the enemy, said to number nearly four hundred, advanced, and under protection of the neighboring cabins laid siege to the fort. The fighting continued throughout the day, and traditional accounts have related many incidents such as have marked the heroic defense of many western frontier posts. Women and children assisted in the work of reloading the guns, moulding bullets and watching every move of the enemy. The garrison was outnumbered nearly ten to one, but every assault on the stockade was repelled. Such a fortification as that at Wheeling was practically impregnable to Indian attack. Unless cannon were used to breach the walls, or the structure could be set on fire, the defenders could shoot down their assailants with little danger to themselves” (Charles A. Wingerter, History of Greater Wheeling and Vicinity [Chicago: Lewis Publishing], 1912, http://wheeling.weirton.lib.wv.us/history/landmark/historic/fthenry.htm, accessed on April 21, 2012). The account book of Francis Duke, deputy commissary for Ohio County, for the period of June 3-September 17, 1777, lists Robinson and several other men stationed at Fort Henry, including Captains Samuel Mason and Joseph Ogle. (Draper Manuscripts, Virginia Papers, 7ZZ8-22.) After August 30, entries in the account book were made in a different hand—because Duke was killed that day. (William Hintzen, The Border Wars of the Upper Ohio Valley, 1769–1794: Conflicts and Resolutions [Manchester, Conn.: Precision Shooting, Inc.], 1999.)

38. Brackenridge, Views of Louisiana, 164.

39. Louisiana Gazette, October 26, 1811; Major Thomas Biddle, Camp Missouri, Missouri River, to Colonel Henry Atkinson, October 29, 1819, American State Papers, p. 202.

40. Bradbury, Travels, 99–100; Irving, Astoria, 178.

41. Bradbury, Travels, 103.

42. Ibid., 103–4, bracketed insertions added.

43. Ibid., 104–5, bracketed insertion added.

44. Ibid., 105–6.

45. Ibid., 106–9, bracketed insertion added.

46. Ibid., 110, 117.

47. Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 115; Bradbury, Travels, 119; Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 128.

48. Bradbury, Travels, 119, bracketed insertion added.

49. Ibid., 121; Irving, Astoria, 189; Bradbury, Travels, 122.

50. Ibid., 121; Irving, Astoria, 189; Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 128.

51. Bradbury, Travels, 122.

52. Ibid.

53. Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 129–30.

54. Ibid., 135.

55. Ibid., 135–36.

56. Ibid., 138, 139.

57. Irving, Astoria, 214; Chittenden, American Fur Trade, 2:685.

58. Reed Journal, July 8, July 15-17, August 29, 1811; Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 166, 167.

59. Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage, 149.

60. Bradbury, Travels, 168, 182, 183.