3 Calm

PESSIMISM

A pessimist is someone who calmly assumes from the outset, and with a great deal of justification, that things tend to turn out very badly in almost all areas of existence. Strange though it can sound, pessimism is one of the greatest sources of serenity and contentment.

The reasons are legion. Relationships are rarely if ever the blissful marriage of two minds and hearts that Romanticism teaches us to expect; sex is invariably an area of tension and longing; creative endeavour is pretty much always painful, compromised and slow; any job – however appealing on paper – will be irksome in many of its details; children will always resent their parents, however well intentioned and kindly the adults may try to be. Politics is evidently a process of muddle and dispiriting compromise.

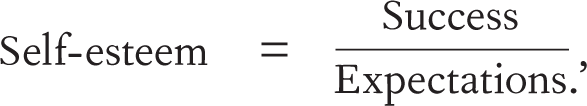

Our degree of satisfaction is critically dependent on our expectations. The greater our hopes, the greater the risks of rage, bitterness, disappointment and a sense of persecution. We are not always humiliated by failing at things; we are humiliated only if we first invested our pride and sense of worth in a given achievement and then did not reach it. Our expectations determine what we will interpret as a triumph and what must count as a failure. ‘With no attempt there can be no failure; with no failure no humiliation. So our self-esteem in this world depends entirely on what we back ourselves to be and do,’ wrote the psychologist William James. ‘It is determined by the ratio of our actualities to our supposed potentialities … thus:

The problem with our world is that it does not stop emphasizing that success, calm, happiness and fulfilment could, somehow, one day be ours. And in this way it never ceases to torture us.

As with optimists, pessimists would like things to go well. But by recognizing that many things can – and probably will – go wrong, the pessimist is adroitly placed to secure the good outcome both parties ultimately seek. It is the pessimist who, having never expected anything to go right, ends up with one or two things to smile about.

RAGE

However illogical rage can look, it is never right to dismiss it as merely beyond understanding or control. It operates according to a universal underlying rationale: we shout because we are hopeful.

How badly we react to frustration is ultimately determined by what we think of as normal. We may be irritated that it is raining, but our pessimistic accommodation to the likelihood of its doing so means we are unlikely ever to respond to a downpour by screaming. Our annoyance is tempered by what we understand can be expected of existence. We aren’t overwhelmed by anger whenever we are frustrated; only when we first believed ourselves entitled to a particular satisfaction and then did not receive it. Our furies spring from events which violate a background sense of the rules of existence.

And yet we too often have the wrong rules. We shout when we lose the house keys because we somehow believe in a world in which belongings never go astray. We lose our temper at being misunderstood by our partner because something has convinced us that we are not irredeemably alone.

So we must learn to disappoint ourselves at leisure before events take us by surprise. We must be systematically inducted into the darkest realities – the stupidities of others, the ineluctable failings of technology, the eventual destruction of all that we cherish – while we are still capable of a relative measure of rational control.

ANXIETY

Anxiety is not a sign of sickness, a weakness of the mind or an error for which we should always seek a medical solution. It is mostly a hugely reasonable and sensitive response to the genuine strangeness, terror, uncertainty and riskiness of existence.

Anxiety is our fundamental state for well-founded reasons: because we are intensely vulnerable physical beings, a complicated network of fragile organs all biding their time before eventually letting us down catastrophically at a moment of their own choosing; because we have insufficient information upon which to make most major life decisions; because we can imagine so much more than we have and live in ambitious mediatized societies where envy and restlessness are a constant; because we are the descendants of the great worriers of the species, the others having been trampled and torn apart by wild animals; because we still carry in our bones – into the calm of the suburbs – the terrors of the savannah; because the trajectories of our careers and of our finances are plotted within the tough-minded, competitive, destructive, random workings of an uncontained economic engine; because we rely for our self-esteem and sense of comfort on the love of people we cannot control and whose needs and hopes will never align seamlessly with our own.

In her great novel Middlemarch, the nineteenth-century English writer George Eliot, a deeply self-aware but also painfully anxious figure, reflected on what it would be like if we were truly sensitive, open to the world and felt the implications of everything: ‘If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.’

Eliot’s lines offer us a way to reinterpret our anxiety with greater benevolence. It emerges from a dose of clarity that is (currently) too powerful for us to cope with, but isn’t for that matter wrong. We panic because we rightly feel how thin the veneer of civilization is, how mysterious other people are, how improbable it is that we exist at all, how everything that seems to matter now will eventually be annihilated, how random many of the turnings of our lives are, how much we are prey to accident.

Anxiety is simply insight that we haven’t yet found a productive use for, that hasn’t yet made its way into art or philosophy.

Which is not to say that there aren’t better and worse ways to approach our condition. The single most important move is acceptance. There is no need – on top of everything else – to be anxious that we are anxious. The mood is no sign that our lives have gone wrong, merely that we are alive. We should also be more careful when pursuing things we imagine will spare us anxiety. We can head for them by all means, but for other reasons than fantasies of calm, and with a little less vigour and a little more scepticism. We will still be anxious when we finally have the house, the relationship and the right income.

We should at all points spare ourselves the burden of loneliness. We are far from the only ones to be suffering. Everyone is more anxious than they are inclined to tell us. Even the tycoon and the couple in love are in pain. We have collectively failed to admit to ourselves how much anxiety is our default state.

We must, when possible, learn to laugh about our anxieties, laughter being the exuberant expression of relief when a hitherto private agony is given a well-crafted social formulation in a joke. We may have to suffer alone, but we can at least hold out our arms to our similarly tortured, fractured and, above all else, anxious neighbours, as if to say, in the kindest way possible, ‘I know …’

Anxiety deserves greater dignity. It is not a sign of degeneracy, rather a kind of masterpiece of insight: a justifiable expression of our mysterious participation in a disordered, uncertain world.

THE NEED TO BE ALONE

Because our culture places such a high value on sociability, it can be deeply awkward to have to explain how much, at certain points, we need to be alone.

We may try to pass off our desire as something work-related – people generally understand a need to finish a project. But, in truth, a far less respectable and more profound desire may be driving us on: unless we are alone, we are at risk of forgetting who we are.

We, the ones who are asphyxiated without periods by ourselves, take other people very seriously – perhaps more seriously than those in the uncomplicated ranks of the endlessly gregarious. We listen closely to stories, we give ourselves to others, we respond with emotion and empathy. But as a result we cannot keep swimming in company indefinitely.

At a certain point, we have had enough of conversations that take us away from our own thought processes, enough of external demands that stop us heeding our inner tremors, enough of the pressure for superficial cheerfulness that denies the legitimacy of our latent melancholy – and enough of robust common sense that flattens our peculiarities and less well-charted ideas.

We need to be alone because life among other people unfolds too quickly. The pace is relentless: the jokes, the insights, the excitements. There can sometimes be enough in five minutes of social life to take up an hour of analysis. It is a quirk of our minds that not every emotion that impacts us is at once fully acknowledged, understood or even – as it were – truly felt. After time among others, there are myriad sensations that exist in an ‘unprocessed’ form within us. Perhaps an idea that someone raised made us anxious, prompting inchoate impulses for changes in our lives. Perhaps an anecdote sparked off an envious ambition that is worth decoding and listening to in order to grow. Maybe someone subtly fired an aggressive dart at us and we haven’t had the chance to realize we are hurt. We need quiet to console ourselves by formulating an explanation of where the nastiness might have come from. We are more vulnerable and tender-skinned than we’re encouraged to imagine.

By retreating into ourselves, it looks as if we are the enemies of others, but our solitary moments are in reality a homage to the richness of social existence. Unless we’ve had time alone, we can’t be who we would like to be around our fellow humans. We won’t have original opinions. We won’t have lively and authentic perspectives. We’ll be – in the wrong way – a bit like everyone else.

We’re drawn to solitude not because we despise humanity but because we are properly responsive to what the company of others entails. Extensive stretches of being alone may in reality be a precondition for knowing how to be a better friend and a properly attentive companion.

THE IMPORTANCE OF STARING OUT OF THE WINDOW

We tend to reproach ourselves for staring out of the window. Most of the time, we are supposed to be working, or studying, or ticking things off a to-do list. It can seem almost the definition of wasted time. It appears to produce nothing, to serve no purpose. We equate it with boredom, distraction, futility. The act of cupping our chin in our hands near a pane of glass and letting our eyes drift in the middle distance does not enjoy high prestige. We don’t go around saying, ‘I had a great day today. The high point was staring out of the window.’ But maybe, in a better society, this is exactly what people would quietly say to one another.

The point of staring out of a window is, paradoxically, not to find out what is going on outside. It is, rather, an exercise in discovering the contents of our own minds. It is easy to imagine we know what we think, what we feel and what’s going on in our heads. But we rarely do entirely. There’s a huge amount of what makes us who we are that circulates unexplored and unused. Its potential lies untapped. It is shy and doesn’t emerge under the pressure of direct questioning. If we do it right, staring out of the window offers a way for us to be alert to the quieter suggestions and perspectives of our deeper selves. Plato suggested a metaphor for the mind: our ideas are like birds fluttering around in the aviary of our brains. But in order for the birds to settle, Plato understood that we need periods of purpose-free calm. Staring out of the window offers such an opportunity. We see the world going on: a patch of weeds is holding its own against the wind; a grey tower block looms through the drizzle. But we don’t need to respond, we have no overarching intentions, and so the more tentative parts of ourselves have a chance to be heard, like the sound of church bells in the city once the traffic has died down at night.

The potential of daydreaming isn’t recognized by societies obsessed with productivity. But some of our greatest insights come when we stop trying to be purposeful and instead respect the creative potential of reverie. Window daydreaming is a strategic rebellion against the excessive demands of immediate, but in the end insignificant, pressures in favour of the diffuse, but very serious, search for the wisdom of the unexplored deep self.

NATURE

Nature corrects our erroneous, and ultimately very painful, sense that we are essentially free. The idea that we have the freedom to fashion our own destinies as we please has become central to the contemporary world view: we are encouraged to imagine that we can, with time, create exactly the lives we desire, around our relationships, our work and existence more generally. This hopeful scenario has been the source of extraordinary and unnecessary suffering.

There are many things we want desperately to avoid, which we will spend huge parts of our lives worrying about and which we will then bitterly resent when they force themselves upon us nevertheless.

The idea of inevitability is central to the natural world: the deciduous tree has to shed it leaves when the temperature dips in autumn; the river must erode its banks; the cold front will deposit its rain; the tide has to rise and fall. The laws of nature are governed by forces nobody has chosen, no one can resist and which brook no exception.

When we contemplate nature (a forest in the autumn, for example, or the reproductive cycle of the salmon), we are thinking about rules that in their broad, irresistible structure apply to ourselves as well. We too must mature, seek to reproduce, age, fall ill and die. We face a litany of other burdens too: we will never be fully understood by others; we will always be burdened by primordial anxiety; we will never fully know what it is like to be someone else; we will invariably fantasize about more than we can have; we will realize we cannot – in key ways – be who we would wish.

What we most fear can happen irrespective of our desires. But when we see frustration as a law of nature, we drain it of some of its sting and bitterness. We recognize that limitations are not in any way unique to us. In awesome, majestic scenes (the life of an elephant; the eruption of a volcano), nature moves us away from our habitual tendency to personalize and rail against our lot.

Sometimes we respond quite negatively to encounters with things that are much larger and more powerful than ourselves. It’s a feeling that can strike us when we are alone in a new city, trying to negotiate a vast railway terminus or the huge underground system at rush hour, and we sense that no one knows anything about us or cares in the least for our confusion. The scale of the place forces upon us the unwelcome fact that we don’t matter in the greater scheme of things and that what is of great concern to us doesn’t figure at all in the minds of others. It’s a crushing, lonely experience that intensifies anxiety and agitation.

But there’s another way an encounter with the large-scale can affect us – and calm us down – that philosophers have called ‘the sublime’. Heading back to the airport after a series of frustrating meetings, we notice the sun setting behind the mountains. Tiers of clouds are bathed in gold and purple, while huge slanting beams of light cut across the urban landscape. To record the feeling without implying anything mystical, it seems as if one’s attention is being drawn up into the radiant gap between the clouds and the summits, and that one is for a moment merging with the cosmos. Normally the sky isn’t a major focus of attention, but now it’s mesmerizing. For a while it doesn’t seem to matter so much what happened in the office or that the contract will – maddeningly – have to be renegotiated by the legal team.

At this moment, nature seems to be sending us a humbling message: the incidents of our lives are not terribly important. And yet, strangely, rather than being distressing, this sensation can be a source of immeasurable solace and calm.

Things that have up to now been looming large in our minds (something has gone wrong with the Singapore discussion, a colleague has behaved coldly, there’s been disagreement about patio furniture) are cut down in size. The sublime drags us away from the minor details which normally – and inevitably – occupy our attention and makes us concentrate on what is truly major. The encounter with the sublime undercuts the gradations of human status and makes everyone – at least for a time – look relatively unimpressive. Next to the mighty canyon or the vast ocean, even the celebrity or the CEO does not seem so mighty.

Deserts offer particular respite in this context. Year by year little changes: a few more stones will crumble from the mesa; a few plants will eke out an existence; the same pattern of light and shadow will be endlessly repeated. Caring about having a larger office or being worried that one’s car has a small scratch over the left rear wheel or that the sofa is looking a bit moth-eaten doesn’t make much sense against the enormity of time and space. Differences in accomplishments, standing and possessions that torment us in the cities don’t feel especially exciting or impressive when considered from the emotional state that a desert induces. Things happen on the scale of centuries. Today and tomorrow are essentially the same. Your existence is a small, temporary thing. You will die and it will be as if you had never been.

It could sound demeaning. But these are generous sentiments when we otherwise so easily suffer by exaggerating our own importance. We are truly minute and entirely dispensable. The sublime does not humble us by exalting others; it gives a sense of the lesser status of all of wretched humanity.

In the late eighteenth century, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant thought ‘the starry heavens above’ were the most sublime spectacle in nature and that contemplation of this transcendent sight could hugely assist us in coping with our travails. Although Kant was interested in the developing science of astronomy, he saw the field as primarily serving a major psychological purpose. Unfortunately, since then, the advances in astrophysics have become increasingly embarrassed around this aspect of the stars. It would seem deeply odd today if in a science class there were a special section not on the fact that Aldebaran is an orange-red giant star of spectral and luminosity type K5+III and that it is currently losing mass at a rate of (1–1.6) × 10-11 M⦿ yr-1 with a velocity of 30 km s-1 but rather on the ways in which the sight of stars can help us manage our emotional lives and relations with our families – even though knowing how to cope better with anxiety is in most lives a more urgent and important task than steering one’s rocket around the galaxies. Although we’ve made vast scientific progress since Kant’s time, we haven’t properly explored the potential of space as a source of wisdom, as opposed to a puzzle for astrophysicists to unpick.

On an evening walk you look up and see the planets Venus and Jupiter shining in the darkening sky. As the dusk deepens you might see Andromeda and Aries. It’s a hint of the unimaginable extensions of space across the solar system, the galaxy, the cosmos. They were there, quietly revolving, their light streaming down, as spotted hyenas warily eyed a Stone Age settlement; and as Julius Caesar’s triremes set out after midnight to cross the Channel and reach the cliffs of England’s south coast at dawn. The sight has a calming effect because none of our troubles, disappointments or hopes have any relevance. Whatever happens to us, whatever we do, is of no consequence from the point of view of the universe.

And though we know that the moon is a lifeless accumulation of galactic debris, we might make a point of watching it emerge – as a representative of an entirely different perspective within which our own concerns are mercifully irrelevant.

A central task of culture should be to remind us that the laws of nature apply to us as well as to trees, clouds and cliff faces. Our goal is to get clearer about where our own tantalizingly powerful yet always limited agency stops: where we will be left with no option but to bow to forces infinitely greater than our own.

ACCEPTANCE

The more calm matters to us, the more we will be aware of all the very many times when we have been less calm than we should. We’ll be sensitive to our own painfully frequent bouts of irritation and upset. It can feel laughably hypocritical. Surely a genuine devotion to calm would mean ongoing serenity? But this isn’t a fair judgement, because being calm all the time isn’t ever a viable option. What counts is the commitment one is making to the idea of being a little calmer than last year. We can legitimately count as lovers of calm when we ardently seek to grow calmer, not when we succeed at being calm on all occasions. However frequent the lapses, it is the devotion that matters.

Furthermore, it is a psychological law that those who are most attracted to calm will almost certainly also be especially irritable and by nature prone to particularly high levels of anxiety. We have a mistaken picture of what lovers of calm look like if we assume them to be among the most tranquil of the species.

Typically, lovers of something are not the people who already possess it but those who are hugely aware of how much they lack it – and are therefore especially humble before, and committed to, the task of securing it.