THE DANGERS OF THE GOOD CHILD

Good children do their homework on time; their writing is neat; they keep their bedroom tidy; they are often a little shy; they want to help their parents; they use their brakes when cycling down a hill.

Because they don’t pose many immediate problems, we tend to assume that all is well with good children. They aren’t the target of particular concern; that goes to the kids who are graffitiing the underpass. People imagine the good children must be fine, on the basis that they do everything that is expected of them.

And that, of course, is precisely the problem. The secret sorrows – and future difficulties – of the good boy or girl begin with their inner need for excessive compliance. The good child isn’t good because, by a quirk of nature, they simply have no inclination to be anything else. They are good because they have been granted no other option, because the more transgressive part of what they are cannot be tolerated. Their goodness springs from necessity rather than choice.

Good children may be good out of love for a depressed parent who makes it clear that they just couldn’t cope with any more complications or difficulties. Or maybe they are very good to soothe a violently angry parent who could become catastrophically frightening at any sign of less than perfect conduct.

This repression of more challenging emotions, though it generates short-term cordiality, stores up an immense amount of difficulty for later life. Practised educators and parents will spot signs of exaggerated politeness and treat it as the danger it is.

Good children become the keepers of too many secrets and the appalling communicators of unpopular but important things. They say lovely words, they are experts in satisfying the expectations of their audiences, but their real thoughts and feelings are buried, then seep out as psychosomatic symptoms, twitches, sudden outbursts, sulphurous bitterness and an underlying feeling of unreality.

The good child has been deprived of one of the central ingredients of a properly privileged upbringing: the experience of other people witnessing and surviving their mischief.

Grown up, the good child typically has particular problems around sex. They might once have been praised for their purity. Sex, in its necessary extremes and ecstasies, lies at the opposite end of the spectrum. They may in response disavow their desires and detach themselves from their bodies, or perhaps give in to their longings only in a furtive, addictive, disproportionate or destructive way that leaves them feeling disgusted and distinctly frightened.

At work, the good adult also faces problems. As a child, it was enough to follow the rules, never to make trouble and to avoid provoking the merest frustration. But a cautious approach cannot tide one satisfactorily across an adult life. Almost everything interesting, worth doing or important will meet with a degree of opposition. The greatest plan will necessarily irritate or disappoint certain people – while remaining eminently valuable. Every noble ambition has to skirt disaster and ignominy. In their timid inability to brook the dangers of hostility, the good child risks being condemned to career mediocrity and sterile people-pleasing.

Being properly mature involves a frank, unfrightened relationship with one’s own darkness, complexity and ambition. It involves accepting that not everything that makes us happy will please others or be honoured as especially ‘nice’, but it can be important to explore and hold on to it nevertheless.

The desire to be good is one of the loveliest things in the world, but in order to have a genuinely good life, we may sometimes need to be (by the standards of the good child) fruitfully and bravely bad.

CONFIDENCE AND THE INNER IDIOT

In well-meaning attempts to boost our confidence ahead of challenging moments, we are often encouraged to pay attention to our strengths: our intelligence, our competence, our experience.

But this can – curiously – have awkward consequences. There’s a type of under-confidence that arises specifically when we grow too attached to our own dignity and become anxious around situations that seem in some way to threaten it. We hold back from challenges in which there is any risk of ending up looking ridiculous, but these of course comprise many of the most interesting options.

In a foreign city, we grow reluctant to ask anyone to guide us, because they might think us an ignorant, pitiable lost tourist. We might long to be close to someone, but never let on out of a fear that they might have caught sight of our absurd inner self. Or at work we don’t apply for a promotion, in case this reminds the senior management of their underlying wish to fire us. In a concerted bid never to look foolish, we don’t venture very far from our lair; and thereby – from time to time, at least – miss out on the best opportunities of our lives.

At the heart of our under-confidence is a skewed picture of how dignified a normal person can be. We imagine that it might be possible to place ourselves permanently beyond mockery. We trust that it is an option to lead a good life without regularly making a wholehearted idiot of ourselves.

One of the most charming books written in early modern Europe is In Praise of Folly (1511) by the Dutch scholar and philosopher Erasmus. Erasmus advances a liberating argument. In a warm tone, he reminds us that everyone, however important and learned they might be, is a fool. No one is spared, not even the author. However well schooled he himself was, Erasmus remained – he insists – as much of a nitwit as anyone else: his judgement is faulty, his passions get the better of him, he is prey to superstition and irrational fear, he is shy whenever he has to meet new people, he drops things at elegant dinners. This is deeply cheering, for it means that our own repeated idiocies do not have to exclude us from the best company. Looking like a prick, making blunders and doing bizarre things in the night don’t render us unfit for society; they just make us a bit more like the greatest scholar of the Northern European Renaissance.

There’s a similarly uplifting message to be taken from the work of Pieter Bruegel. His central work, Dutch Proverbs, presents a comically disenchanted view of human nature. Everyone, he suggests, is pretty much deranged: here’s a man throwing his money into the river; there’s a soldier squatting on the fire and burning his trousers; someone is intently bashing his head against a brick wall, while another is biting a pillar. Importantly, the painting is not an attack on just a few unusually awful people: it’s a picture of parts of all of us.

The works of Bruegel and Erasmus propose that the way to greater confidence isn’t to reassure ourselves of our own dignity; it’s to live at peace with the inevitable nature of our ridiculousness. We are idiots now, we have been idiots in the past and we will be idiots again in the future – and that is OK. There aren’t any other available options for human beings.

We grow timid when we allow ourselves to be overexposed to the respectable sides of others. Such are the pains people take to appear normal, we collectively create a phantasm – problematic for everyone – which suggests that reasonableness and respectability might be realistic possibilities.

But once we learn to see ourselves as already, and by nature, foolish, it really doesn’t matter so much if we do one more thing that might threaten us with a verdict of idiocy. The person we try to love could indeed think us ridiculous. The individual we asked directions from in a foreign city might regard us with contempt. But if these people did so, it wouldn’t be news to us; they would only be confirming what we had already gracefully accepted in our hearts long ago: that we, like them – and every other person on the earth – are on frequent occasions a nitwit. The risk of trying and failing would have its sting substantially removed. The fear of humiliation would no longer stalk us in the shadows of our minds. We would become free to give things a go by accepting that failure and idiocy were the norm. And every so often, amid the endless rebuffs we’d have factored in from the outset, it would work: we’d get a hug, we’d make a friend, we’d get a pay rise.

The road to greater confidence begins with a ritual of telling oneself solemnly every morning, before embarking on the challenges of the day, that one is a muttonhead, a cretin, a dumb-bell and an imbecile. One or two more acts of folly should, thereafter, not feel so catastrophic after all.

IMPOSTOR SYNDROME

Faced with hurdles, we often leave the possibility of success to others, because we don’t seem to ourselves to be anything like the sorts of people who win. When we approach the idea of acquiring responsibility or prestige, we quickly become convinced that we are simply – as we see it – ‘impostors’, like an actor in the role of a pilot, wearing the uniform and delivering authoritative cabin announcements while being incapable of starting the engines.

The root cause of impostor syndrome is an unhelpful picture of what people at the top of society are really like. We feel like impostors not because we are uniquely flawed, but because we can’t imagine how equally flawed the elite must necessarily also be underneath their polished surfaces.

Impostor syndrome has its roots far back in childhood – specifically in the powerful sense children have that their parents are really very different from them. To a four-year-old, it is incomprehensible that their mother was once their age and unable to drive a car, call the plumber, decide other people’s bedtimes and go on trips with colleagues. The gulf in status appears absolute and unbridgeable. The child’s passionate loves – bouncing on the sofa, Pingu, Toblerone … – have nothing to do with those of adults, who like to sit at a table talking for hours (when they could be rushing about outside) and drink beer (which tastes of rusty metal). We start out in life with a very strong impression that competent and admirable people are really not like us at all.

This childhood experience dovetails with a basic feature of the human condition. We know ourselves from the inside, but others only from the outside. We’re constantly aware of all our anxieties and doubts from within, yet all we know of others is what they happen to do and tell us, a far narrower and more edited source of information. We are very often left to conclude that we must be at the more freakish, revolting end of human nature.

But really we’re just failing to imagine that others are every bit as fragile and strange as we are. Without knowing what it is that troubles or racks outwardly impressive people, we can be sure that it will be something. We might not know exactly what they regret, but they will have agonizing feelings of some kind. We won’t be able to say exactly what kind of unusual kink obsesses them, but there will be one. And we can know this because vulnerabilities and compulsions cannot be curses that have just descended upon us uniquely; they are universal features of the human mental condition.

The solution to the impostor syndrome lies in making a leap of faith and trusting that others’ minds work basically in much the same way as our own. Everyone is probably as anxious, uncertain and wayward as we are.

Traditionally, being a member of the aristocracy provided a fast-track to confidence-giving knowledge about the true characters of the elite. In eighteenth-century England, an admiral of the fleet would have looked deeply impressive to outsiders (meaning more or less everyone), with his splendid uniform (cockaded hat, abundant gold) and hundreds of subordinates to do his bidding. But to a young earl or marquess who had moved in the same social circles all his life, the admiral would appear in a very different light. He would have seen the admiral losing money at cards in their club the night before; he would know that the admiral’s pet name in the nursery was ‘Sticky’ because of his inept way of eating; his aunt would still tell the story of the ridiculous way the admiral tried to proposition her sister in the yew walk; he would know that the admiral was in debt to his grandfather, who regarded him as pretty dim. Through acquaintance, the aristocrat would have reached a wise awareness that being an admiral was not an elevated position reserved for gods; it was the sort of thing Sticky could do.

The other traditional release from under-confidence of this type came from the opposite end of the social spectrum: being a servant. ‘No man is a hero to his valet,’ remarked the sixteenth-century essayist Montaigne – a lack of respect which may at points prove deeply encouraging, given how much our awe can sap our will to rival or match our heroes. Great public figures aren’t ever so impressive to those who look after them, who see them drunk in the early hours, examine the stains on their underpants, hear their secret misgivings about matters on which they publicly hold firm views and witness them weeping with shame over strategic blunders they officially deny.

The valet and the aristocrat reasonably and automatically grasp the limitations of the authority of the elite. Fortunately, we don’t have to be either of them to liberate ourselves from inhibiting degrees of respect for the powerful; imagination will serve just as well. One of the tasks that works of art should ideally accomplish is to take us more reliably into the minds of people we are intimidated by and show us the more average, muddled and fretful experiences unfolding inside.

At another point in his Essays, Montaigne playfully informed his readers in plain French that ‘Kings and philosophers shit and so do ladies.’

Montaigne’s thesis is that for all the evidence that exists about this shitting, we might not guess that grand people ever had to squat over a toilet. We never see distinguished types doing this – while, of course, we are immensely well informed about our own digestive activities. And therefore we build up a sense that because we have crude and sometimes rather desperate bodies, we can’t be philosophers, kings or ladies; and that if we were to set ourselves up in these roles, we’d just be impostors.

With Montaigne’s guidance, we are invited to take on a saner sense of what powerful people are actually like. But the real target isn’t just an under-confidence about bodily functions; it is psychological timidity. Montaigne might have said that kings, philosophers and ladies are racked by self-doubt and feelings of inadequacy, sometimes bump into doors and have odd-sounding thoughts about members of their own families. Furthermore, instead of considering only the big figures of sixteenth-century France, we could update the example and refer to CEOs, corporate lawyers, news presenters and successful start-up entrepreneurs. They too can’t cope, feel they might buckle under pressure and look back on certain decisions with shame and regret. No less than shitting, such feelings belong to us all. Our inner frailties don’t cut us off from doing what they do. If we were in their roles, we’d not be impostors, we’d simply be normal.

Making a leap of faith around what other people are like helps to humanize the world. Whenever we encounter a stranger we’re not really encountering such a person, we’re encountering someone who is – in spite of surface evidence to the contrary – in basic ways very much like us, and therefore nothing fundamental stands between us and the possibility of responsibility, success and fulfilment.

FAME

Fame seems to offer very significant benefits. The fantasy unfolds like this: when you are famous, wherever you go, your good reputation will precede you. People will think well of you, because your merits have been impressively explained in advance. You will receive warm smiles from admiring strangers. You won’t need to make your own case laboriously on each occasion. When you are famous, you will be safe from rejection. You won’t have to win over every new person. Fame means that other people will be flattered and delighted even if you are only slightly interested in them. They will be amazed to see you in the flesh. They’ll ask to take a photo with you. They’ll sometimes laugh nervously with excitement. Furthermore, no one will be able to afford to upset you. When you’re not pleased with something, it will become a big problem for others. If you say your hotel room isn’t up to scratch, the management will panic. Your complaints will be taken very seriously. Your happiness will become the focus of everyone’s efforts. You will make or break other people’s reputations. You’ll be boss.

The desire for fame has its roots in the experience of neglect and injury. No one would want to be famous who hadn’t also, somewhere in the past, been made to feel extremely insignificant. We sense the need for a great deal of admiring attention when we have been painfully overexposed to deprivation. Perhaps our parents were hard to impress. They never noticed us much, as they were so busy with other things, focusing on other famous people, unable to have or express kind feelings, or just working too hard. There were no bedtime stories and our school reports weren’t the subject of praise and admiration. That’s why we dream that one day the world will pay attention. When we’re famous, our parents will have to admire us too (which throws up an insight into one of the great signs of good parenting: that a child has no desire to be famous).

But even if our parents were warm and full of praise, there might still be a problem. It might be that it was the buffeting and indifference of the wider world (starting in the school playground) that were intolerable after all the early years of adulation at home. We might have emerged from familial warmth and been mortally hurt that strangers were not as kind and understanding as we had come to expect. The crushing experience of humiliation might even have been vicarious: our mother being rudely dismissed by a waiter; our father standing awkwardly alone.

What is common to all dreams of fame is that being known to strangers will often be the solution to a hurt. It presents itself as the answer to a deep need to be appreciated and treated decently by other people.

And yet fame cannot, in truth, accomplish what is being asked of it. It does have advantages, which are evident. But it also introduces a new set of very serious disadvantages, which the modern world refuses to view as structural rather than incidental. Every new famous person who disintegrates, breaks down in public or loses their mind is judged in isolation, rather than being interpreted as a victim of an inevitable pattern within the pathology of fame.

One wants to be famous out of a desire for kindness. But the world isn’t generally kind to the famous for very long. The reason is basic: the success of any one person involves humiliation for lots of others. The celebrity of a few people will always contrast painfully with the obscurity of the many. Witnessing the famous upsets people. For a time, the resentment can be kept under control, but it is never somnolent for very long. When we imagine fame, we forget that it is inextricably connected to being too visible in the eyes of some, to bugging them unduly, to coming to be seen as the plausible cause of their humiliation: a symbol of how the world has treated them unfairly.

So, soon enough, the world will start to go through the old pronouncements of the famous, it will comment negatively on their appearance, it will pore over their setbacks, it will judge their relationships, it will mock their new ventures.

Fame makes people more, not less, vulnerable, because it leaves them open to unlimited judgement. Everyone is wounded by a cruel assessment of their character or merit. But the famous have an added challenge in store. The assessments will flood in from legions of people who would never dare to say to their faces what they can now express from the safety of the newspaper office or screen. We know from our own lives that a nasty remark can take a day or two to recover from.

Psychologically, the famous are of course the very last people on earth to be well equipped to deal with what they’re going through. After all, they only became famous because they were wounded, because they had thin skin; because they were in some respects mentally unwell. And now, far from compensating them adequately for their disease, fame aggravates it exponentially. Strangers will voice their negative opinions in detail, unable or simply unwilling to imagine that famous people bleed far more quickly than anyone else. They might even think that the famous aren’t listening (though one wouldn’t become famous if one didn’t suffer from a compulsion to listen too much).

Every worst fear about themselves (that they are stupid, ugly, not worthy of existence) will daily be actively confirmed by strangers. They will be exposed to the fact that people they have never met, people for whom they have nothing but goodwill, actively loathe them. They will learn that detestation of their personality is – in some quarters – a badge of honour. Sometimes the attacks will be horribly insightful. At other times they’ll make no sense to anyone who really knows the situation. But the criticisms will lodge in people’s minds nevertheless, and no lawyer, court case or magician will ever be able to delete them.

Needless to say, a hurt celebrity won’t be eligible for sympathy. The very concept of a deserving celebrity is a joke, about as moving for the average person as the sadness of a tyrant.

To sum up, fame really just means that someone gets noticed a great deal, not that they are more intensely understood, appreciated or loved.

At an individual level, the only mature strategy is to give up on fame. The aim that lay behind the desire for fame remains important. One does still want to be appreciated and understood. But the wise person accepts that celebrity does not actually provide these things. Appreciation and understanding are only available through individuals one knows and cares about, not via groups of a thousand or a million strangers. There is no short cut to friendship – which is what the famous person is in effect seeking.

For those who are already famous, the only way to retain a hold on a measure of sanity is to stop listening to what the wider world is saying. This applies to the good things as much as to the bad. It is best not to know. The wise person knows that their products require attention. But they make a clear distinction between the purely practical needs of marketing and advocacy and the intimate desire to be liked and treated with justice and kindness by people they don’t know.

At a collective, political level we should pay great attention to the fact that so many people (particularly young ones) today want to be famous – and even see fame as a necessary condition for a successful life. Rather than dismiss this wish, we should grasp its underlying and worrying meaning: they want to be famous because they do not feel respected, because citizens have forgotten how to accord one another the degree of civility, appreciation and decency that everyone craves and deserves. The desire for fame is a sign that an ordinary life has ceased to be good enough.

The solution is not to encourage ever more people to become famous, but to put greater efforts into encouraging a higher level of politeness and consideration for everyone, in families and communities, in workplaces, in politics, in the media, at all income levels, especially modest ones. A healthy society will give up on the understandable but erroneous belief that fame might guarantee that truly valuable goal: the kindness of strangers.

SPECIALIZATION

One of the greatest sorrows of work stems from a sense that only a small portion of our talents is taken up and engaged by the job we are paid to do every day. We are likely to be so much more than our labour allows us to be. The title on our business card is only one of thousands of titles we theoretically possess.

In his ‘Song of Myself’, published in 1855, the American poet Walt Whitman gave our multiplicity memorable expression: ‘I am large, I contain multitudes.’ By this he meant that there are always so many interesting, attractive and viable versions of oneself, so many good ways one could potentially live and work, and yet very few of these ever get properly enacted in the course of the single life we have. No wonder that we’re quietly and painfully conscious of our unfulfilled destinies, and at times recognize with a legitimate sense of agony that we really could well have been something and someone else.

The big economic reason why we can’t explore our potential as we might is that it is hugely more productive for us not to do so. In The Wealth of Nations (1776), the Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith first explained how what he termed the ‘division of labour’ was at the heart of the increased productivity of capitalism. Smith zeroed in on the dazzling efficiency that could be achieved in pin manufacturing, if everyone focused on one narrow task (and stopped, as it were, exploring their Whitman-esque ‘multitudes’):

One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business; to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, all performed by distinct hands. I have seen a small manufactory where they could make upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they could have made perhaps not one pin in a day.

Adam Smith was astonishingly prescient. Doing one job, preferably for most of one’s life, makes perfect economic sense. It is a tribute to the world Smith foresaw – and helped to bring into being – that we have all ended up doing such specific jobs and carry such puzzling titles as Senior Packaging & Branding Designer, Intake and Triage Clinician, Research Centre Manager, Risk and Internal Audit Controller and Transport Policy Consultant. We have become tiny, relatively wealthy cogs in giant, efficient machines. And yet, in our quiet moments, we reverberate with private longings to give our multitudinous selves expression.

One of Adam Smith’s most intelligent and penetrating readers was the German economist Karl Marx. Marx agreed entirely with Smith’s analysis: specialization had indeed transformed the world and possessed a revolutionary power to enrich individuals and nations. But where he differed from Smith was in his assessment of how desirable this development might be. We would certainly make ourselves wealthier by specializing, but we would also, as Marx pointed out, dull our lives and cauterize our talents. In describing his utopian communist society, Marx placed enormous emphasis on the idea of everyone having many different jobs. There were to be no specialists here. In a pointed dig at Smith in The German Ideology (1846), Marx wrote:

In communist society … nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes … thus it is possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner … without ever becoming a hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.

Part of the reason why the job we do, as well as the jobs we don’t get to do, matters so much is that our occupation decisively shapes who we are. How exactly our characters are marked by work is often hard for us to notice – our outlooks just feel natural to us – but we can observe the identity-defining nature of work well enough in the presence of practitioners from different fields. The primary school teacher treats even the middle-aged a little as if they were in need of careful shepherding; the psychoanalyst has a studied way of listening and seeming not to judge while exuding a pensive, reflective air; the politician lapses into speeches at intimate dinner parties. Every occupation weakens or reinforces aspects of our nature. There are jobs that keep us constantly tethered to the immediate moment (A&E nurse, news editor); others that focus our attention on the outlying fringes of the time horizon (futurist, urban planner, reforester). Certain jobs daily sharpen our suspicions of our fellow humans, suggesting that the real agenda must always be far from what is overtly being said (journalist, antiques dealer); others intersect with people at the candid, intimate moments of their lives (anaesthetist, hairdresser, funeral director). In some jobs, it is clear what you have to do to move forward and how promotion occurs (civil servant, lawyer, surgeon), a dynamic that lends calm and steadiness to the soul, and diminishes tendencies to plot and manoeuvre; in others (television producer, politician), the rules are muddied and seem bound up with accidents of friendship and fortuitous alliances, encouraging tendencies to anxiety, distrust and shiftiness.

The psychology inculcated by work doesn’t neatly stay at work; it colours the whole of who we end up being. We start to behave across our whole lives like the people work has required us to be in our productive hours. Along the way, this narrows character. When certain ways of thinking become called for daily, others start to feel peculiar or threatening. By giving a large part of one’s life over to a specific occupation, one necessarily has to perform an injustice to other areas of latent potential. Whatever enlargements it offers our personalities, work also possesses a powerful capacity to trammel our spirits.

We can ask ourselves the poignant autobiographical question: what sort of person might I have been had I had the opportunity to do something else? There will be parts of us that we’ve had to kill (perhaps rather brutally) or that lie in shadow, twitching occasionally on late Sunday afternoons. Contained within other career paths are other plausible versions of ourselves which, when we dare to contemplate them, reveal important, but undeveloped or sacrificed, options.

We are meant to be monogamous about our work and yet truly have talents for many more jobs than we will ever have the opportunity to explore. We can understand the origins of our restlessness when we look back at our childhoods. As children, in a single Saturday morning, we might put on an extra jumper and imagine being an Arctic explorer, then have brief stints as an architect making a Lego house, a rock star making up an anthem about cornflakes and an inventor working out how to speed up colouring in by gluing four felt-tip pens together. We might then put in a few minutes as a member of an emergency rescue team before trying out being a pilot brilliantly landing a cargo plane on the rug in the corridor; we’d perform a life-saving operation on a knitted rabbit and finally we’d find employment as a sous-chef helping make a ham and cheese sandwich for lunch. Each one of these ‘games’ might have been the beginning of a career. And yet we had to settle on only a single option, pursued unremittingly for half a century.

Compared to the play of childhood, we’re all leading fatally restricted lives. There is no easy cure. As Adam Smith argued, the causes don’t lie in some personal error we’re making. It’s a limitation forced upon us by the greater logic of a competitive market economy. But we can allow ourselves to mourn that there will always be large aspects of our character that won’t be satisfied. We’re not being silly or ungrateful. We’re simply registering the clash between the demands of the employment market and the free, wide-ranging potential of every human life. There’s a touch of sadness to this insight. But it is also a reminder that this sense of being unfulfilled will accompany us in whatever job we choose: we can’t overcome it by switching jobs. No one job can ever be enough.

There’s a parallel here – as so often – between our experience at work and what happens in relationships. There’s no doubt that we could (without any blame attaching to a current partner) have successful relationships with dozens, even hundreds of different people. Each would bring to the fore different sides of our personality, please us (and upset us) in different ways and introduce us to new excitements. Yet, as with work, specialization brings advantages: it means we can focus, bring up children in stable environments and learn the disciplines of compromise. In love and work, life requires us to be specialists even though we are by nature equally suited for wide-ranging exploration. And so we will necessarily carry about within us, in embryonic form, many alluring versions of ourselves which will never be given the proper chance to live. It’s a sombre thought but a consoling one too. Our suffering is painful but, in its commonality, has a curious dignity to it as well, for it applies as much to the CEO as to the intern, to the artist as to the accountant. Everyone could have found so many versions of happiness that will elude them. In suffering in this way, we are participating in the common human lot. We may with a certain melancholic pride remove the job search engine from our bookmarks and cancel our subscription to a dating site in due recognition of the fact that – whatever we do – parts of our potential will have to go undeveloped and have to die without ever having had the chance to come to full maturity – for the sake of the benefits of focus and specialization.

ARTISTS AND SUPERMARKET TYCOONS

Shanghai-based Xu Zhen is one of the most celebrated Chinese artists of the age. He operates in a variety of media, including video, sculpture and fine art. His work displays a deep interest in business; he appears at once charmed and horrified by commercial life. In recent years, he has become especially fascinated by supermarkets. He’s interested, in part, in how lovely they can be. He likes the alluring packaging, the abundance (the feel of lifting something off a shelf and seeing multiple versions of it waiting just behind) and the exquisite precision with which items are displayed. He particularly likes the claim of comprehensiveness that supermarkets implicitly make: the suggestion that they can, within their cavernous interiors, provide us with everything we could possibly need to thrive.

At the same time, Xu Zhen feels there’s something very wrong with real supermarkets, and commercial life in general. The actual products they sell often aren’t the things we genuinely need. Despite the enormous choice, what we require to thrive isn’t on offer. Meanwhile, the backstories of the brightly coloured things on sale are often exploitative and dark. Everything has been carefully calculated to get us to spend more than we mean to. Cynicism permeates the whole system.

In response, the Chinese artist mocks supermarkets repeatedly. His work involves recreating, at a very large scale, entire supermarkets in galleries and museums. The products in these supermarkets look real, you’re invited to pick them up, but then you find out they are empty, as physically empty as Xu Zhen feels they are spiritually incomplete. His checkouts are similarly deceptive. They seem genuine: you scan your products at a high-tech counter, but you then get a receipt which turns out to be a fake; you’ve bought ‘nothing’ of value.

The supermarket installation takes us on a journey. At first it is getting us to share the artist’s excitement around supermarkets and then it’s puncturing the illusion: it’s a gigantic, deliberate let-down. It’s highly significant that Xu Zhen’s critique of supermarkets is ironic. We tend to become ironic around things that we feel disappointed by but don’t think we’ll ever be able to change. It’s a manoeuvre of disappointment stoically handled. A lot of art is ironic in its critiques of capitalism; we’ve come to expect this. It mocks all that is wrong but has no alternatives to put forward. A kind of hollow laughter seems the only fitting response to the compromises of commercial life.

Xu Zhen is trapped in the paradigm of what an artist does. A real artist, we have come to suppose – and the current ideology of the art world insists – couldn’t be enthusiastic about improving a supermarket. He or she could only mock from the sidelines. Nowadays, fortunately, we’ve loosened old highly restrictive definitions of what a ‘real’ man or a ‘real’ woman might be like, but there remain comparably strict social taboos hemming in the idea of what a ‘real’ artist is allowed to get up to. They can be as experimental and surprising as they like … unless they want to run a food shop or an airline or an energy corporation, at which point they cross a decisive boundary, fall from grace, lose their special status as artists and become the supposed polar opposites: mere business people.

We should take Xu Zhen seriously, perhaps more seriously than he takes himself. Beneath the irony, Xu Zhen has the ambition to discover what an ideal supermarket might be like, how it might be a successful business and how capitalism could be reformed. Somewhere within his project, he carries a hope: that a corporation like a supermarket could be brought into line with the best values of art and assume psychological and spiritual importance inside the framework of commerce.

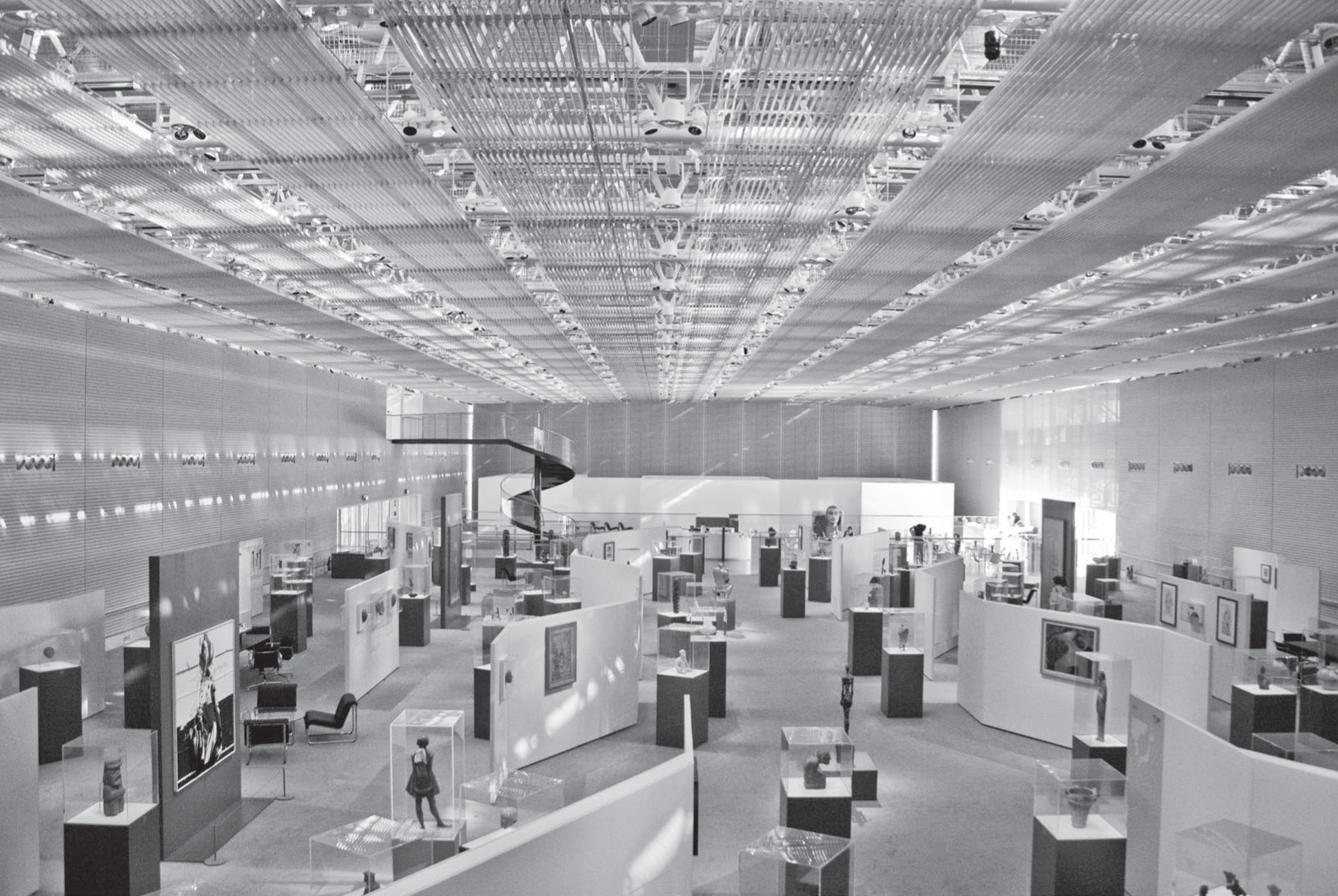

Thousands of miles away from Shanghai, in the flatlands of East Anglia, lies an elegant modern building completed in 1978 by the architect Norman Foster. The Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts is filled with some of the greatest works of contemporary art. Here we find masterpieces by Henry Moore, Giacometti and Francis Bacon. The collection is made possible thanks to the enormous wealth of the Sainsbury family, who own and run Britain’s second-largest supermarket chain. Discounted shoulders of lamb, white bread and special two-for-one offers on satsumas have led to exquisite display cases containing Giacometti’s elongated, haunting figures and Barbara Hepworth’s hollowed-out ovaloids. The gallery seems guided by values that are light years from any actual supermarket. It is intent on feeding the soul and the patrons and curators are deeply ambitious about the emotional and educational benefit of the experience: they want you to come out cleansed and improved.

From a very different direction, the Sainsbury family arrived at a strikingly similar conclusion to Xu Zhen. Art and supermarkets are essentially opposed. And like Xu Zhen, they are caught in an identity trap, though this is a very different one: the identity trap of the philanthropist. The philanthropist has been imagined as a person who makes a lot of money in the brutish world of commerce, with all the normal expectations of maximizing returns, squeezing wages and focusing on obvious opportunities, and then makes a clean break. In their spare hours, they can devote their wealth to projects that are profoundly non-commercial: the patient collection of Roman coins, Islamic vases or modern sculptures. But philanthropists know that if they ever took an art-loving attitude to their businesses these might suffer economic collapse. Instead of making big things happen in the real world, they would become mere artists who make little interesting things in the sheltered, subsidized world of the gallery.

The situation is strangely tantalizing. The artist finds a little that is lovable and much that’s wrong around supermarkets, but can’t imagine running or bringing the ideals of art into action in one. The supermarket owners love art, but can’t imagine bringing their psychologically and aesthetically ambitious sides into focus in their business. These two parties are both like pioneers, at the edge of unexplored territory. There is a huge idea they are both circling round. The goal is a synthesis of business and art: a supermarket that is truly guided by the ideals of art, a capitalism that is compatible with the higher values of humanity.

Up to now, we have collectively learned to admire the values of the arts (which can be summed up as a devotion to truth, beauty and goodness) in the special arena of galleries. But their more important application is in the general, daily fabric of our lives – the area that’s currently dominated by an often depleted vision of commerce. It’s a tragic polarization: we encounter the values we need, but only in a rarefied setting, while we regard these values as alien to the circumstances in which we most need to meet them. For most of history, artists have laboured to render a few square inches of canvas utterly perfect or to chisel a single block of stone into its most expressive form. Traditionally, the most common size for a work of art was between three and six feet across. And while artists have articulated their visions across such expanses, the large-scale projects have been given over wholesale to businesses and governments, which have generally operated with much lower ambitions. We’re so familiar with this polarization, we regard it as if it were an inevitable fact of nature, rather than what it really is: a cultural and commercial failing.

Ideally artists should absorb the best qualities of business and vice versa. Rather than seeing such qualities as opposed to what they stand for as artists or business people, they should see them as great enabling capacities which help them fulfil their missions to the world. Xu Zhen will probably never get to build an airport, a marina, an old people’s home or a supermarket, but the ideal next version of him will. We should want to simultaneously raise and combine the ambitions of artists (to make the noblest concepts powerful in our lives) and of business (to serve us in a deep sense successfully).

CONSUMER SOCIETY

Since time immemorial, the overwhelming majority of the earth’s inhabitants have owned more or less nothing: the clothes they stood up in, some bowls, a pot and a pan, perhaps a broom and, if things were going well, a few farming implements. Nations and peoples remained consistently poor, with global GDP not growing at all from year to year. The world was in aggregate as hard up in 1800 as it had been at the beginning of time. Then, starting in the early eighteenth century, in the countries of north-western Europe, a remarkable phenomenon occurred: economies began to expand and wages to rise. Families who had never before had any money beyond what they needed to survive found they could go shopping for small luxuries: a comb or a mirror, a spare set of underwear, a pillow, some thicker boots or a towel. Their expenditure created a virtuous economic circle: the more they spent, the more businesses grew, the more wages rose. By the mid-eighteenth century, observers recognized that they were living through a period of epochal change that historians have since described as the world’s first ‘consumer revolution’. In Britain, where the changes were most marked, enormous new industries sprang up to cater for the widespread demand for goods that had once been the preserve of the very rich alone. In the cities, it was possible to buy furniture made by Chippendale, Hepplewhite and Sheraton, porcelain made by Wedgwood and Crown Derby, and cutlery from the manufacturers of Sheffield, while hats, shoes and dresses featured in bestselling journals such as The Gallery of Fashion and The Lady’s Magazine. Styles for clothes and hair, which had formerly gone unchanged for decades, now altered every year, often in extremely theatrical and impractical directions. In the early 1770s, there was a craze for decorated wigs so tall that their tops could be accessed only by standing on a chair. It was fun for the cartoonists. So vivid and numerous were the consumer novelties that the austere Dr Johnson wryly wondered whether prisoners were soon ‘to be hanged in a new way’ too.

The Christian Church also looked on and did not approve. Up and down the country, clergymen delivered bitter sermons against the new materialism. Sons and daughters were to be kept away from shops; God would not look kindly on those who paid more attention to household decoration than to the state of their souls.

But along with the consumer revolution there now emerged an intellectual revolution that sharply altered the understanding of the role of ‘vanities’ in an economy. In 1705, a London physician called Bernard Mandeville published an economic tract (unusually but charmingly written in verse) entitled The Fable of the Bees, which proposed that – contrary to centuries of religious and moral thinking – what made countries rich (and therefore safe, honest, generous-spirited and strong) was a very minor, unelevated and apparently undignified activity: shopping for pleasure. It was the consumption of what Mandeville called ‘fripperies’ – hats, bonnets, gloves, butter dishes, soup tureens, shoehorns and hair clips – that provided the engine for national prosperity and allowed the government to do in practice what the Church only knew how to sermonize about in theory: make a genuine difference to the lives of the weak and the poor. The one way to generate wealth, argued Mandeville, was to ensure high demand for absurd and unnecessary things. Of course, no one needed embroidered handbags, silk-lined slippers or ice creams, but it was a blessing that they could be prompted by fashion to want them, for on the back of demand for such trifles workshops could be built, apprentices trained and hospitals funded. Rather than condemn recreational expenditure, as Christian moralists had done, Mandeville celebrated them for their consequences. As his subtitle put it, it was a case of ‘Private Vices, Public Benefits’:

It is the sensual courtier who sets no limit to his luxury, the fickle strumpet who invents new fashions every week and the profuse rake and the lavish heir who most effectively help the poor. He that gives most trouble to thousands of his neighbours and invents the most operose manufactures is, right or wrong, the greatest friend to society. Mercers, upholsterers, tailors and many others would be starved in half a year’s time if pride and luxury were at once to be banished from the nation.

Mandeville shocked his audience with the starkness of the choice he placed before them. A nation could either be very high-minded, spiritually elevated, intellectually refined, and dirt poor, or a slave to luxury and idle consumption, and very rich.

Mandeville’s dark thesis went on to convince almost all the great anglophone economists and political thinkers of the eighteenth century. In his essay ‘Of Luxury’ (1752), the philosopher David Hume repeated Mandeville’s defence of an economy built on making and selling unnecessary things: ‘In a nation, where there is no demand for superfluities, men sink into indolence, lose all enjoyment of life, and are useless to the public, which cannot maintain or support its fleets and armies.’ The ‘superfluities’ were clearly silly, Hume was in no doubt, but they paved the way for something very important and grand: military and welfare spending.

There were, nevertheless, some occasional departures from the new economic orthodoxy. One of the most spirited and impassioned voices was that of Switzerland’s greatest philosopher, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Shocked by the impact of the consumer revolution on the manners and atmosphere of his native Geneva, he called for a return to a simpler, older way of life, of the sort he had experienced in Alpine villages or read about in travellers’ accounts of the native tribes of North America. In the remote corners of Appenzell or the vast forests of Missouri, there was – blessedly – no concern for fashion and no one-upmanship around hair extensions. Rousseau recommended closing Geneva’s borders and imposing crippling taxes on luxury goods so that people’s energies could be redirected towards non-material values. He looked back with fondness to the austere martial spirit of Sparta and complained, partly with Mandeville and Hume in mind: ‘Ancient treatises of politics continually made mention of morals and virtue; ours speak of nothing but commerce and money.’ However, even if Rousseau disagreed with Hume and Mandeville, he did not seek to deny the basic premise behind their analyses: it truly appeared to be a choice between decadent consumption and wealth on the one hand, and virtuous restraint and poverty on the other. It was simply that Rousseau – unusually – preferred virtue to wealth.

The parameters of this debate have continued to dominate economic thinking ever since. We re-encounter them in ideological arguments between capitalists and communists and free marketers and environmentalists. But for most of us the debate is no longer pertinent. We simply accept that we will live in consumer economies with some very unfortunate side effects to them (crass advertising, unhealthy foodstuffs, products that are disconnected from any reasonable assessment of our needs, excessive waste …) in exchange for economic growth and high employment. We have chosen wealth over virtue.

The one question rarely asked is whether there might be a way to ameliorate the dispiriting choice, to draw on the best aspects of consumerism on the one hand and high-mindedness on the other without suffering their worst consequences: moral decadence and profound poverty. Might it be possible for a society to develop that allows for consumer spending (and therefore provides employment and welfare) yet of a kind directed at something other than ‘vanities’ and ‘superfluities’? Might we shop for something other than nonsense? In other words, might we have wealth and (a degree of) virtue?

It is a possibility of which we find some intriguing hints in the work of Adam Smith, an economist too often read as a blunt apologist for all aspects of consumer society, but in fact one of its more subtle and visionary analysts. In his The Wealth of Nations, Smith seems at points willing to concede to key aspects of Mandeville’s argument: consumer societies do help the poor by providing employment based around satisfying what are often rather suboptimal purchases. Smith was as ready as other Anglophone economists to mock the triviality of some consumer choices, while admiring their consequences. All those embroidered lace handkerchiefs, jewelled snuff boxes and miniature temples made of cream for dessert were frivolous, he conceded, but they encouraged trade, created employment and generated immense wealth, and could be firmly defended on this score alone.

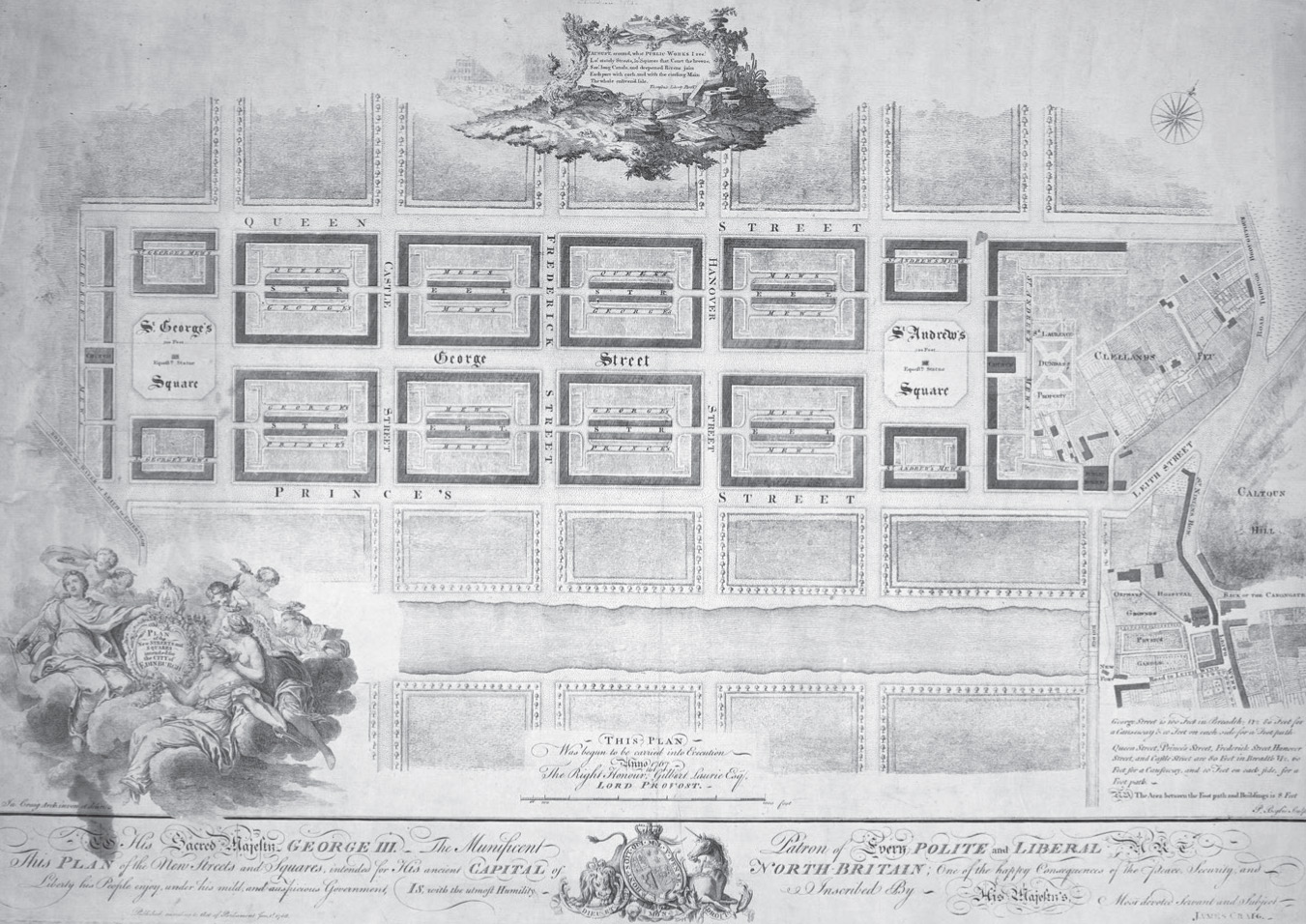

However, Smith offered some fascinating hopes for the future. He pointed out that consumption didn’t invariably have to involve the trading of frivolous things. He had seen the expansion of the Edinburgh book trade and knew how large a market higher education might become. He understood how much wealth was being accumulated through the construction of Edinburgh’s handsome and noble New Town. He understood that humans have many ‘higher’ needs that require a lot of labour, intelligence and work to fulfil, but that lie outside capitalist enterprise as conceived by ‘realists’ like Hume or Mandeville: among them, our need for education, for self-understanding, for beautiful cities and for rewarding social lives. The ultimate goal of capitalism was to tackle ‘happiness’ in all its complexities, psychological as opposed to merely material.

The capitalism of our times still hasn’t entirely come round to resolving the awkward choices that Mandeville and Rousseau circled. But the crucial hope for the future is that we will not forever need to be making money from exploitative or vain consumer appetites; that we will also learn to generate sizeable profits from helping people – as consumers and producers – in the truly important and ambitious aspects of their lives. The reform of capitalism hinges on an odd-sounding but critical task: the conception of an economy focused around higher needs.

HIGHER NEEDS, A PYRAMID AND CAPITALISM

The idea that capitalism can give us what we need has always been central to its defence. More efficiently than any other system, capitalism has, in theory, been able to identify what we’re lacking and deliver it to us with unparalleled efficiency. Capitalism is the most skilled machine we have ever yet constructed for satisfying human needs.

Because businesses have been so extraordinarily productive over the last 200 years, it has become easy to think – in the wealthier parts of the world, at least – that consumer capitalism must by now have reached a stage of exhausted stagnant maturity, which is what may explain both relatively high rates of unemployment and low levels of growth. The heroic period of development, driven in part by breakthroughs in technology, that equipped a mass public in the advanced nations with the basics of food, shelter, hygiene and entertainment, appears to have been brought up against some natural limits. We seem in aggregate to be in the strange position of having rather too much of everything: shoes, dishcloths, televisions, chocolates, woollen hats … In the eyes of some, it is normal that we should have arrived at this end point. The earth and its resources are, after all, limited, so we should not expect growth to be unlimited either. Flatlining reflects the attainment of an enviable degree of maturity. We are ceasing to buy quite so much for an understandable reason: we have all we need.

Yet, despite its evident successes, consumer capitalism cannot in truth realistically be credited with having fulfilled a mission of accurately satisfying our needs, because of one evident failing: we aren’t happy. Indeed, most of us are, a good deal of the time, properly at sea: burdened by complaints, unfulfilled hopes, barely formulated longings, restlessness, anger and grief – little of which our plethora of shops and services appear remotely equipped to address. Given the range of our outstanding needs and capitalism’s theoretical commitment to fulfilling them, it would be profoundly paradoxical to count the economy as in any way mature and beyond expansion. Far from it, it is arguably a good deal too small and desperately undeveloped in relation to what we would truly want from it, having reflected on the full extent of our sorrows and appetites. Despite all the factories, the concrete, the highways and the logistics chains, consumer capitalism has – arguably – not even properly embarked on its tasks. A good future may depend not on minimizing consumer capitalism but on radically extending its reach and depth, via a slightly unfamiliar route: a close study of our unattended needs.

If the proverbial Martian were to attempt to guess what human beings required in order to be satisfied by scanning lists of the top corporations in the leading wealthy countries, they would guess that Homo sapiens had immense requirements for food, warmth, shelter, credit, insurance, missiles, packets of data, strips of cotton or wool to wrap around their limbs and, of course, a lot of ketchup. This, the world’s stock markets seem to tell us, is what human satisfaction is made up of.

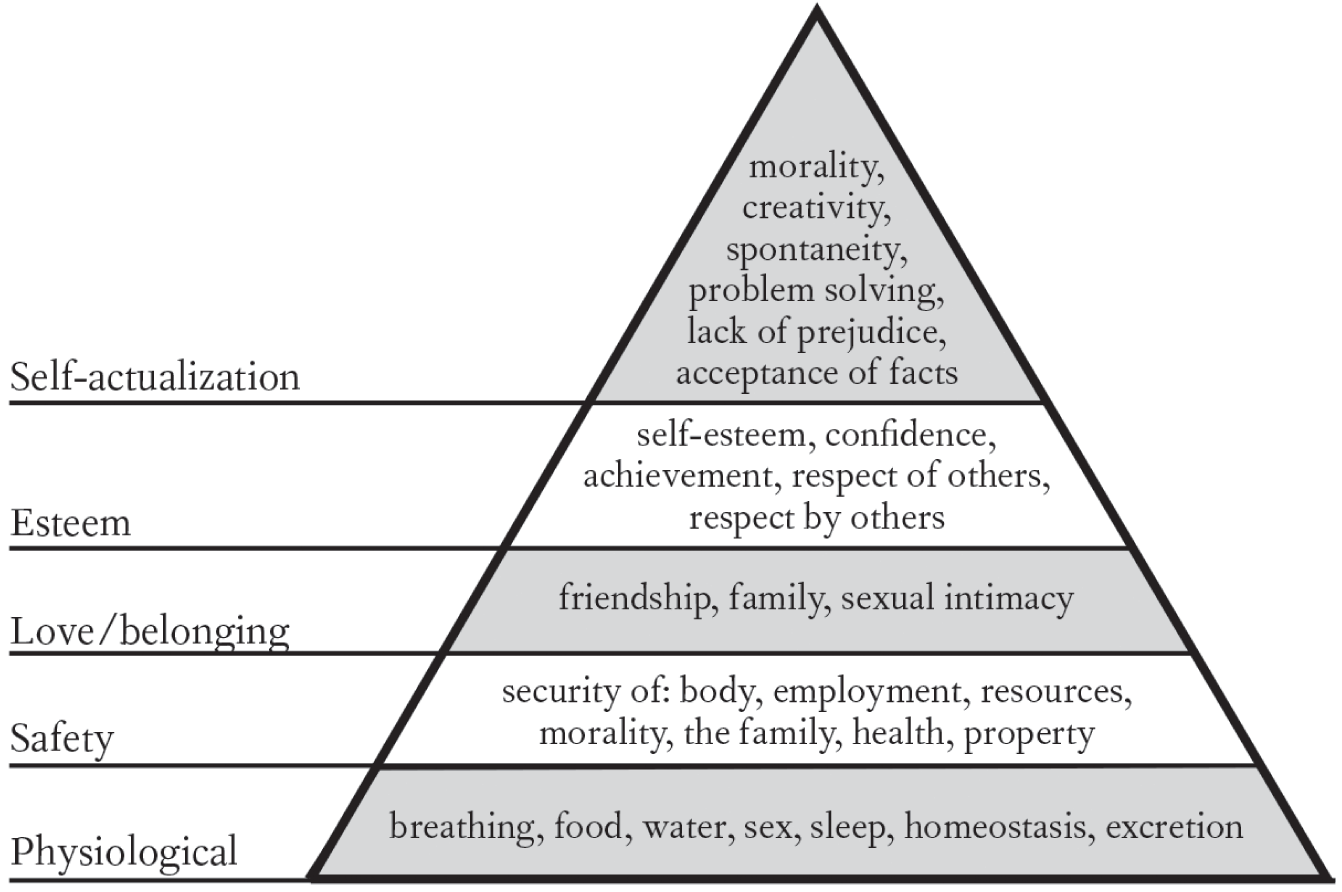

But the reality is naturally more complicated than that. The most concise yet penetrating picture of human needs ever drawn up was the work of a little-known American psychologist called Abraham Maslow. In a paper entitled ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’ published in Psychological Review in 1943, Maslow arranged our longings and appetites in a pyramid-shaped continuum, ranging from what he called the lower needs, largely focused on the body, to the higher needs, largely focused on the psyche and encompassing such elements as the need for status, recognition and friendship. At the apex stood the need for a complete development of our potential, of the kind Maslow had seen in the lives of the cultural figures he most admired: Montaigne, Voltaire, Goethe, Tolstoy and Freud.

If we were to align the world’s largest corporations with the pyramid, we would find that the needs to which they cater are overwhelmingly those at the bottom of the pyramid. Our most successful businesses are those that aim to satisfy our physical and simpler psychological selves: they operate in oil and gas, mining, construction, agriculture, pharmaceuticals, electronics, telecommunications, insurance, banking and light entertainment.

What’s surprising is how little consumer capitalism has, until now, been in any way ambitious about many of the things that deliver higher sorts of satisfaction. Business has helped us to be warm, safe and distracted. It has been markedly indifferent to our flourishing. This is the task ahead of us. The true destiny of and millennial opportunity for consumer capitalism is to travel up the pyramid, to generate ever more of its more profits from the satisfaction of the full range of ‘higher needs’ that currently lie outside the realm of industrialization and commodification.

Capitalists and companies are seemingly – at least semi-consciously – aware of their failure to engage with many of the elements at the top of the pyramid, among them friendship, belonging, meaningfulness and a sense of agency and autonomy. And the evidence for this lies in a rather surprising place, in one of the key institutions for driving the sales of capitalism’s products forwards: advertising.

THE PROMISES OF ADVERTISING

When advertising began in a significant way in the early nineteenth century, it was a relatively straightforward business. It showed you a product, told you what it did, where you could get it and what it cost. Then, in 1960s America, a remarkable new way of advertising emerged, led by such luminaries of Madison Avenue as William Bernbach, David Ogilvy and Mary Wells Lawrence. In their work for brands like Esso, Avis and Life Cereal, adverts ceased to be in a narrow sense about the things they were selling. The focus of an ad might ostensibly be on a car, but our attention was also being directed at the harmonious, handsome couple holding hands beside it. It might on the surface be an advert about soap, but the true emphasis was on the state of calm that accompanied the ablutions. It might be whisky one was being invited to drink, but it was the attitude of resoluteness and resilience on display that provided the compelling focal point. Madison Avenue had made an extraordinary discovery: however appealing a product might be, there were many other things that were likely to be even more appealing to customers – and by entwining their products with these ingredients, sales could be transformed.

Patek Philippe is one of the giants of the global watchmaking industry. Since 1996, they have been running a very distinctive series of adverts featuring parents and children. It is almost impossible not to have glimpsed one somewhere. In one example, a father and son are together in a motorboat, a scene which tenderly evokes filial and paternal loyalty and love. The son is listening carefully while his kindly dad tells him about aspects of seafaring. We can imagine that the boy will grow up confident and independent, yet also respectful and warm. He’ll be keen to follow in his father’s footsteps and emulate his best sides. The father has put a lot of work into the relationship (one senses they’ve been out on the water a number of times) and now the love is being properly paid back. The advertisement understands our deepest hopes around our children. It is moving because what it depicts is so hard to find in real life. We are often brought to tears not so much by what is horrible as by what is beautiful but out of reach.

Father–son relationships tend to be highly ambivalent. Despite a lot of effort, there can be extensive feelings of neglect, rebellion and, on both sides, bitterness. Capitalism doesn’t allow dads to be too present. There may not be so many chances to talk. But in the world of Patek Philippe, we glimpse a psychological paradise.

We turn to Calvin Klein. The parents and children have tumbled together in a happy heap. There is laughter; everyone can be silly together. There is no more need to put up a front, because everyone here is trusting and on the same side. No one understands you like these people do. In the anonymous airport lounge, in the lonely hotel room, you’ll think back to this cosy group and ache. Alternatively, you might already long for those years, quite a way back, when it was so much easier than it’s become. Now the kids are shadowy presences around the house. Your relationship with your spouse has suffered too. Calvin Klein knows this; it too has brilliantly latched on to our deepest and at the same time most elusive inner longings.

Adverts wouldn’t work if they didn’t operate with a very good understanding of what our real needs are; what we truly require to be happy. Their emotional pull is based on knowing us eerily well. As they recognize, we are creatures who hunger for good family relationships, connections with others, a sense of freedom and joy, a promise of self-development, dignity, calm and the feeling that we are respected.

Yet, armed with this knowledge, they – and the corporations who bankroll them – unwittingly play a cruel trick on us, for while they excite us with reminders of our buried longings, they cannot do anything sincere about satisfying them. The objects adverts send us off to buy fall far short of the hopes that they have aroused. Calvin Klein makes lovely cologne. Patek Philippe’s watches are extremely reliable and beautiful agents of timekeeping. But these items cannot by themselves help us secure the psychological possessions our unconscious believed were on offer.

The real crisis of capitalism is that product development lags so far behind the best insights of advertising. Since the 1960s, advertising has worked out just how much we need help with the true challenges of life. It has fathomed how deeply we want to have better careers, stronger relationships, greater confidence. In most adverts, the pain and the hope of our lives have been superbly identified, but the products are almost comically at odds with the problems at hand. Advertisers are hardly to blame. They are, in fact, the victims of an extraordinary problem of modern capitalism. While we have so many complex needs, we have nothing better to offer ourselves, in the face of our troubles, than, perhaps, a slightly more accurate chronometer or a more subtly blended perfume. Business needs to get more ambitious in the creation of new kinds of ‘products’, in their own way as strange-sounding today as a wristwatch would have been to observers in 1500. We need the drive of commerce to get behind filling the world – and our lives – with goods that really can help us to thrive, flourish, find contentment and manage our relationships well.

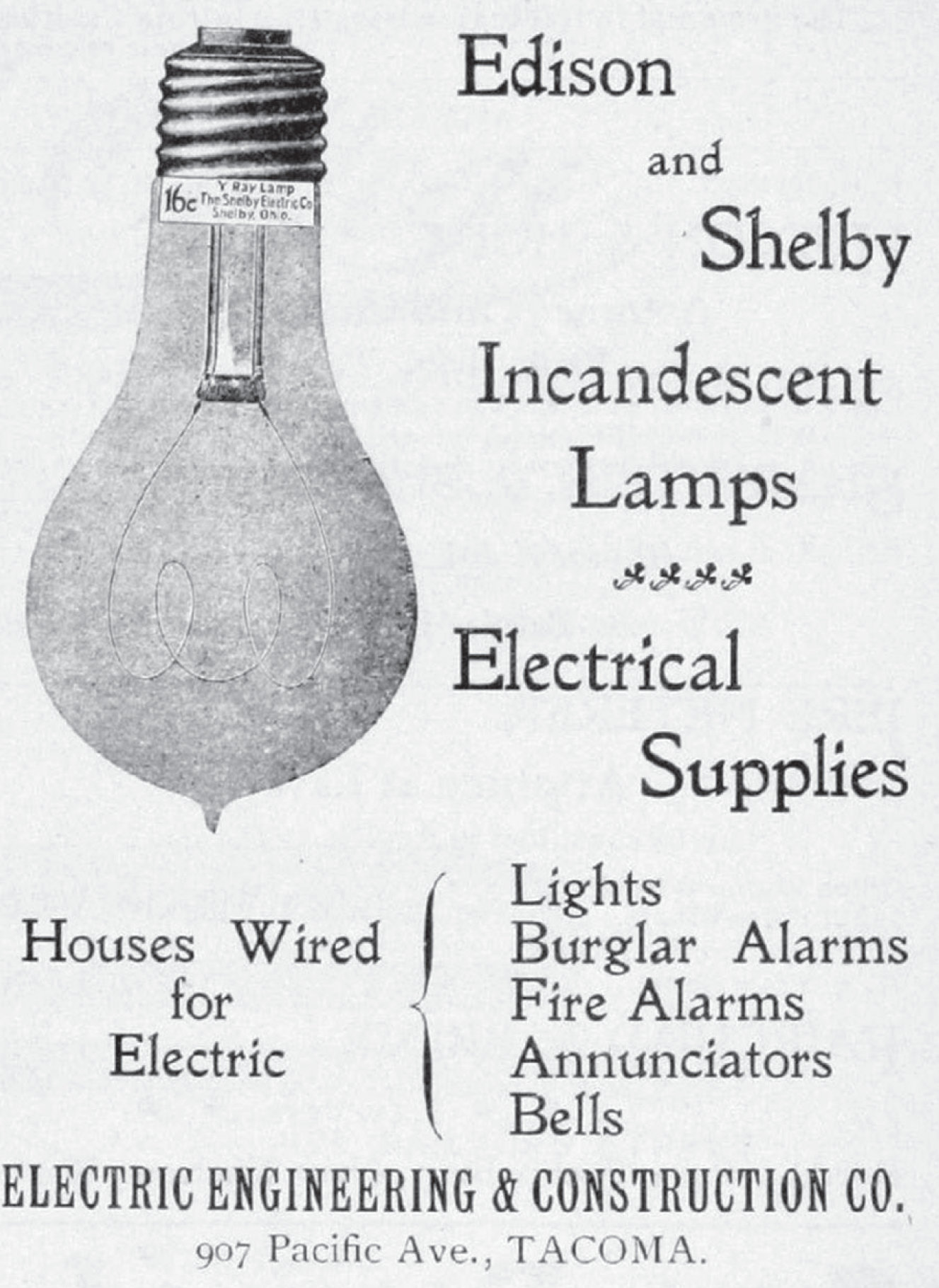

To trace the future shape of capitalism, we have only to think of all our needs that currently lie outside commerce. We need help in forming cohesive, interesting, benevolent communities. We need help in bringing up children. We need help in calming down at key moments (the aggregate cost of our high anxiety and rage is appalling). We need immense help in discovering our real talents in the workplace and in understanding where we can best deploy them. We have aesthetic desires that can’t seem to get satisfied at scale, especially in relation to housing. Our higher needs are not trivial or minor, insignificant things we could easily survive without. They are, in many ways, central to our lives. We have simply accepted, without adequate protest, that there is nothing business can do to address them, when in fact, being able to structure businesses around these needs would be the commercial equivalent of the discovery of steam power or the invention of the electric light bulb.

We don’t know today quite what the businesses of the future will look like, just as half a century ago no one could describe the corporate essence of the current large technology companies. But we do know the direction we need to head in: one where the drive and inventiveness of capitalism tackle the higher, deeper problems of life. This will offer an exit from the failings that attend business today. In the ideal future for consumer capitalism, our materialism would be refined, our work would be rendered more meaningful and our profits more honourable.

Advertising has at least done us the great service of hinting at the future shape of the economy; it already trades in all the right ingredients. The challenge now is to narrow the gap between the fantasies being offered and what we truly spend our lives doing and our money buying.

ARTISTIC SYMPATHY

One of the most troubling aspects of our world is that it contains such enormous disparities in income. At various times, there have been concerted attempts to correct the injustice. Inspired by Marxism, communist governments forcibly seized private wealth and socialist governments have repeatedly tried imposing severely punitive taxes on rich companies and individuals. There have also been attempts to reform the education system, to create positive discrimination in the workplace and to seize the estates of the wealthiest members of society at their deaths.

But the problem of inequality has not gone away and is indeed unlikely to be solved at any point soon, let alone in the short time frame that is relevant to any of us, for a range of stubbornly embedded, partly logical and partly absurd reasons.

However, there is one important move we can make that might take start to reduce some of the sting of inequality. For this, we need to begin by asking what might sound like an offensively obvious question: why is financial inequality a problem?

There are two very different answers. One kind of harm is material: not being able to get a decent house, quality health care, a proper education and a hopeful future for one’s children. But there is also a psychological reason why inequality proves so problematic: because poverty is intricately bound up with humiliation. The punishment of poverty is not limited to money, but extends to the suffering that attends a lack of status: a constant low-level sense that who one is and what one does are of no interest to a world that is punitively unequal in its distribution of honour as well as cash. Poverty not only induces financial harm but damages mental health as well.

Historically, the bulk of political effort has been directed at the first material problem, yet there is also an important move we can make around the psychological issue.

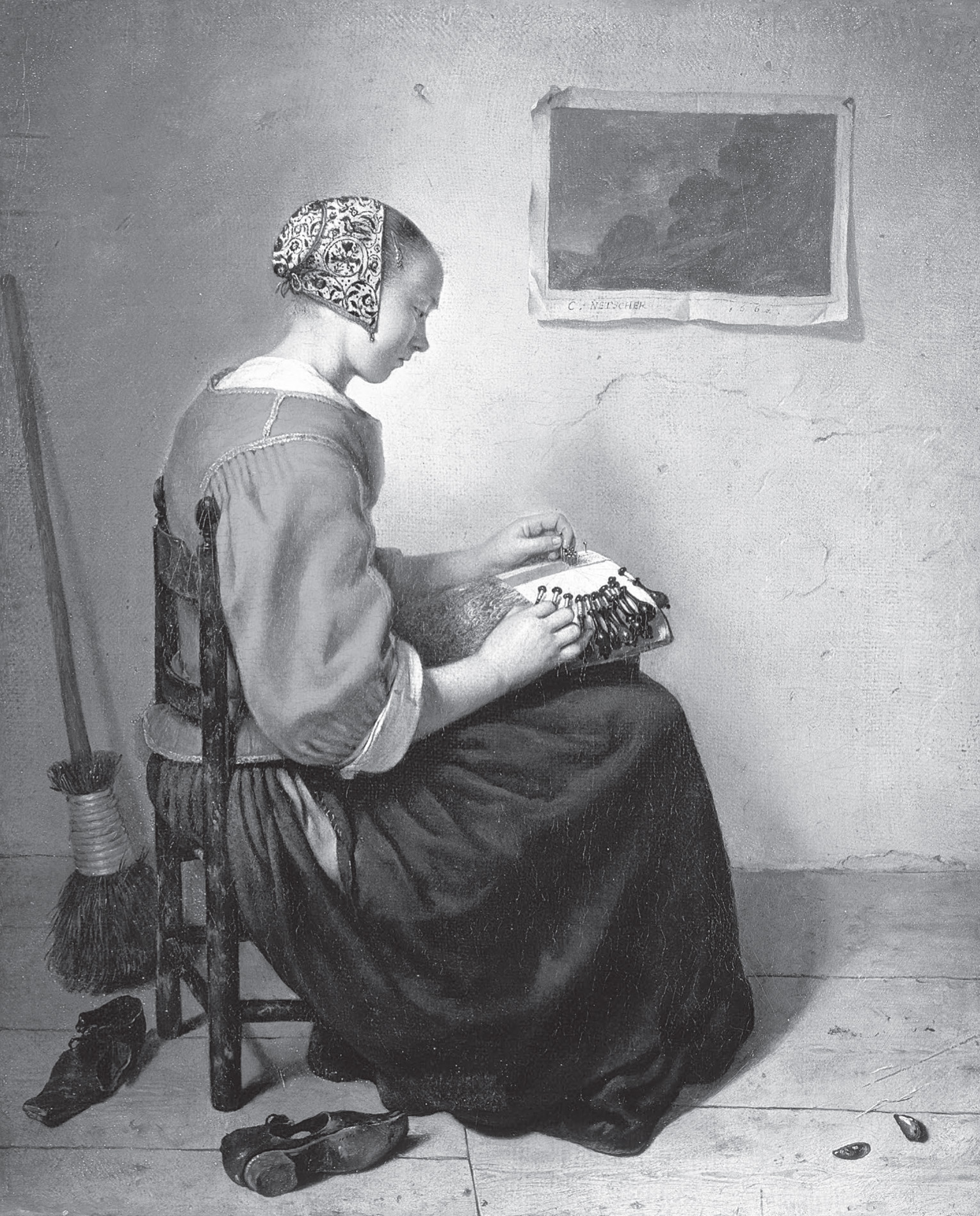

A sketch of a solution to the gap between income and respect lies in a slightly unexpected place: a small painting hanging in a top-floor gallery at London’s Wallace Collection called The Lacemaker, by a little-known Dutch artist, Caspar Netscher, who painted it in 1662.

The artist has caught the woman making lace at a moment of intense concentration on a difficult task. We can feel the effort she is making and can imagine the skill and intelligence she is devoting to her work. Lace was, at the time the painting was created, highly prized. But because many people knew how to make it, the economic law of supply and demand meant that the reward for exquisite craftsmanship was tiny. Lacemakers were among the poorest in society. Were the artist, Caspar Netscher, to be working today, his portrait would have been equivalent to making a short film about phone factory workers or fruit pickers. It would have been evident to all the painting’s viewers that the lacemaker was someone who ordinarily received no respect or prestige at all.

And yet Netscher directed an extraordinary amount of what one might call artistic sympathy towards his sitter. Through his eyes and artistry, she is no longer a nobody. She has grown into an individual, full of her own thoughts, sensitive, serious, devoted – entirely deserving of tenderness and consideration. The artist has transformed how we might look at a lacemaker.

Netscher isn’t lecturing us about respecting the low-paid; we hear this often enough and the lesson rarely sinks in. He’s not trying to use guilt, which is rarely an effective tactic. He’s helping us, in a representative instance, to actually feel respect for his worker rather than just know it might be her due. His picture isn’t nagging, grim or forbidding, it’s an appealing and pleasurable mechanism for teaching us a very unfamiliar but critically important supra-political emotion.

If lots of people saw the lacemaker in the way the artist did, took the lesson properly to heart and applied it widely and imaginatively at every moment of their lives, it is not an exaggeration to say that the psychological burden of poverty would substantially be lifted. The fate of lacemakers, but also office cleaners, warehouse attendants, delivery workers and manual labourers would be substantially improved. This greater sympathy would not be a replacement for political action, it would be its precondition; the sentiment upon which a material change in the lives of the victims of inequality would be founded.

An artist like Netscher isn’t changing how much the low-paid earn; he is changing how the low-paid are judged. This is not an unimportant piece of progress. Netscher was living in an age in which only a very few people might ever see a picture – and of course he was concentrating only on the then current face of poverty. But the process he undertook remains profoundly relevant.

Ideally today our culture would pursue the same project but on a vastly enlarged scale, enticing us via our most successful, popular and widespread art forms to a grand political revolution in feeling, upon which an eventual, firmly based evolution in economic thinking could arise.