ROMANTIC VS. CLASSICAL

As we have seen, we are – each of us – probably a little more one than the other. These categories explain much about us: how we approach nature, what makes us laugh, our political ideas and, of course, our attitudes to love … We may not be used to conceiving of ourselves in these terms, but the labels Romantic and Classical, so often alluded to up to this point, usefully bring into focus some of the central themes of our lives and help us to gain a clearer picture of the underlying structure of our enthusiasms and concerns.

It may be helpful to try finally to pin down a few of the central contrasting characteristics of Romantic and Classical personalities.

Intuition vs. Analysis

Romantics are especially aware of all that lies outside rational explanation, all that cannot neatly be summarized in words. They sense, especially late at night or in the vastness of nature, the scale of the mysteries humanity is up against. The impulse to categorize and to master intellectually is for Romantics a distinct form of vanity, like trying to draw up a list in a hurricane. There is a time when we must surrender to emotion, feel rather than try relentlessly to categorize and make sense of things. We can think too much – and grow sick from trying to pass the complexities of existence through the sieve of the conscious mind. We should more often be guided by our instincts and the voice of nature within us.

Decisions must not always be probed too hard, or moods unpacked. We should respect and not tinker with emotions, especially as they relate to love and the spiritual varieties of experience. We need to fall silent – more frequently than we do – and simply listen. Sometimes the best way to honour the ineffable is through unclear language and obscure modes of expression. The supreme Romantic art form is music.

Classicists like order. They may be moved by the sight of a bilaterally symmetrical avenue of trees extending into the distance as far as the eye can see. They reach for their notebooks during emotional tempests. They don’t believe there could be anything legitimately termed ‘thinking too much’; there is only thinking well or badly. Reason is the sole tool we have available to defend ourselves against primeval chaos.

Classicists know a lot about feelings and intuitions. They have had plenty, often very powerful ones. They just don’t respect them. The last thing they are now inclined to do with an emotion is surrender to it. They have committed too many follies to think that following their hearts might be an idea. They know that not all the mysteries can be explained but they are committed to giving it a shot. They don’t think that love breaks if you examine it too carefully. They favour clear modes of expression (even about rare and evanescent emotions, like reflecting on the Centaurus A galaxy or looking into a partner’s eyes) and a crisp, minimal language that an intelligent twelve-year-old could understand.

Spontaneity vs. Education

Romantics don’t like schools. The best kind of education comes from within. The most important capacities are in us from the start. We don’t need to learn how to love, how to be kind, how to die … Formal learning kills every topic of study. We need to learn to listen to the voice inside us, which will provide us with all we need. There is no greater exemplar of spontaneity than children, and Romantics look upon them with particular tenderness and respect. They are not beasts to be tamed, but gods to be heard. We knew, back then, what mattered. It was school that corrupted us and made us lose our way, which is why it is from the mouths of the very young that we hear truths and sensibilities that the most so-called intelligent adults will have forgotten. To the Romantic, it will always be a child who points out that the emperor is wearing no clothes.

Those of a Classical temperament don’t necessarily respect the education system as it stands – there is so much that could be improved – but the abstract idea of education seems essential and the bedrock of civilization. We didn’t forget how to live; we just never knew, as no one is ever born knowing. Children aren’t any more noble than adults, they just have a particularly hard time containing themselves. The purpose of education is to pass down one or two painfully won insights so that not every generation needs to repeat the same desperate errors.

Honesty vs. Politeness

There is too much hypocrisy already, say the Romantics. We are drowning in our lies and in our compromises. We must do everything to strip away the secrecy our society imposes on us. Authenticity is the highest form of morality. Politeness is a lid that we place upon our real selves to suppress the truths that could free us.

For the Classical person, politeness is the lid we generously place on our inner madness to stop hurting those we care for. Not being ourselves is the kindest thing we can do to someone we claim to love. To give others an uncensored view of our emotions, with their minute-by-minute vagaries and compulsions, is sheer laziness or cruelty. We cannot possibly be good and entirely honest, nor should we try. Strategic inauthenticity is the mark of a kindly soul.

Idealism vs. Realism

The Romantic is excited by how things might ideally be and judges what currently exists in the world by the standard of a better imagined alternative. Most of the time, the current state of society arouses intense disappointment and anger as they consider the injustices, prevarications, compromises and timidity all around. It seems normal to be furious with governments and surprised and outraged by evidence of venal and self-interested conduct in society.

By contrast, the Classical person pays special attention to what can go wrong. They are very concerned to mitigate the downside. They are aware that most things could be a lot worse. Before condemning a government, they consider the standard of governments across history and may regard a current arrangement as bearable, under the circumstances. Their view of people is fundamentally rather dark. They believe that everyone is probably slightly worse than they seem. They feel we have deeply dangerous impulses, lusts and drives and take bad behaviour for granted when it manifests itself. They simply feel this is what humans are prone to. High ideals make them nervous.

Earnestness vs. Irony

Romantics don’t believe in how things are. Their attention is fixed on how they should be. They therefore resist the deflationary call of ironic humour, which seems defeatist. They are earnest in their search for a better future.

The Classical conviction is not that the world is a cheerful place, far from it; but rather that a cheerful mood is a good starting point for living in a radically imperfect and deeply unsatisfactory realm where the priority is to not give up, despair and kill oneself. Ironic humour is a standard recourse for them, because it emerges from the constant collision between how one would want things to be and how it seems they in fact are. They are proponents of gallows humour.

The Rare vs. the Everyday

The Romantic rebels against the ordinary. They are keen on the exotic and the rare. They like things which the mass of the population won’t yet know about. The fact that something is popular will always be a mark against it. They don’t much like routine, especially in domestic life, either. They are anxious about higher things being put under pressure to become ‘useful’ or commercial. They want heroism, excitement and an end to boredom.

The Classical personality welcomes routine as a defence against chaos. They would very much like good things to be popular. They don’t necessarily think that what is presently popular is good, but they see popularity as, in principle, a mark of virtue. They are familiar enough with extremes to welcome things that are a little boring. They can see the charm of doing the laundry.

Purity vs. Ambivalence

The Romantic is dismayed by compromise. They are drawn to either wholehearted endorsement or total rejection. Ideally partners should love everything about each other. A political party should be admirable at every turn. A philanthropist should draw no personal benefit from acts of charity. They feel the attraction of the lost cause. It is very important for the Romantic to feel they are right; winning is, by comparison, not such an urgent matter.

The Classical person takes the view that very few things, and no people, are either wholly good or entirely bad. They assume that there is likely to be some worth in opposing ideas and something to be learned from both sides. It is Classical to think that a decent person might in many areas hold views you find deeply unpalatable.

For a long time now, perhaps since around 1750, Romantic attitudes have been dominant in the Western imagination. The prevailing approach to children, relationships, politics and culture has all been coloured more by a Romantic than by a Classical spirit.

Both Romantic and Classical orientations have important truths to impart. Neither is wholly right or wrong. They need to be balanced. And none of us are in any case ever simply one or the other. But because a good life requires a judicious balance of both positions, at this point in history it might be the Classical attitude whose distinctive claims and wisdom we need to listen to most intently. It is a mode of approaching life which is ripe for rediscovery.

WHY WE HATE CHEAP THINGS

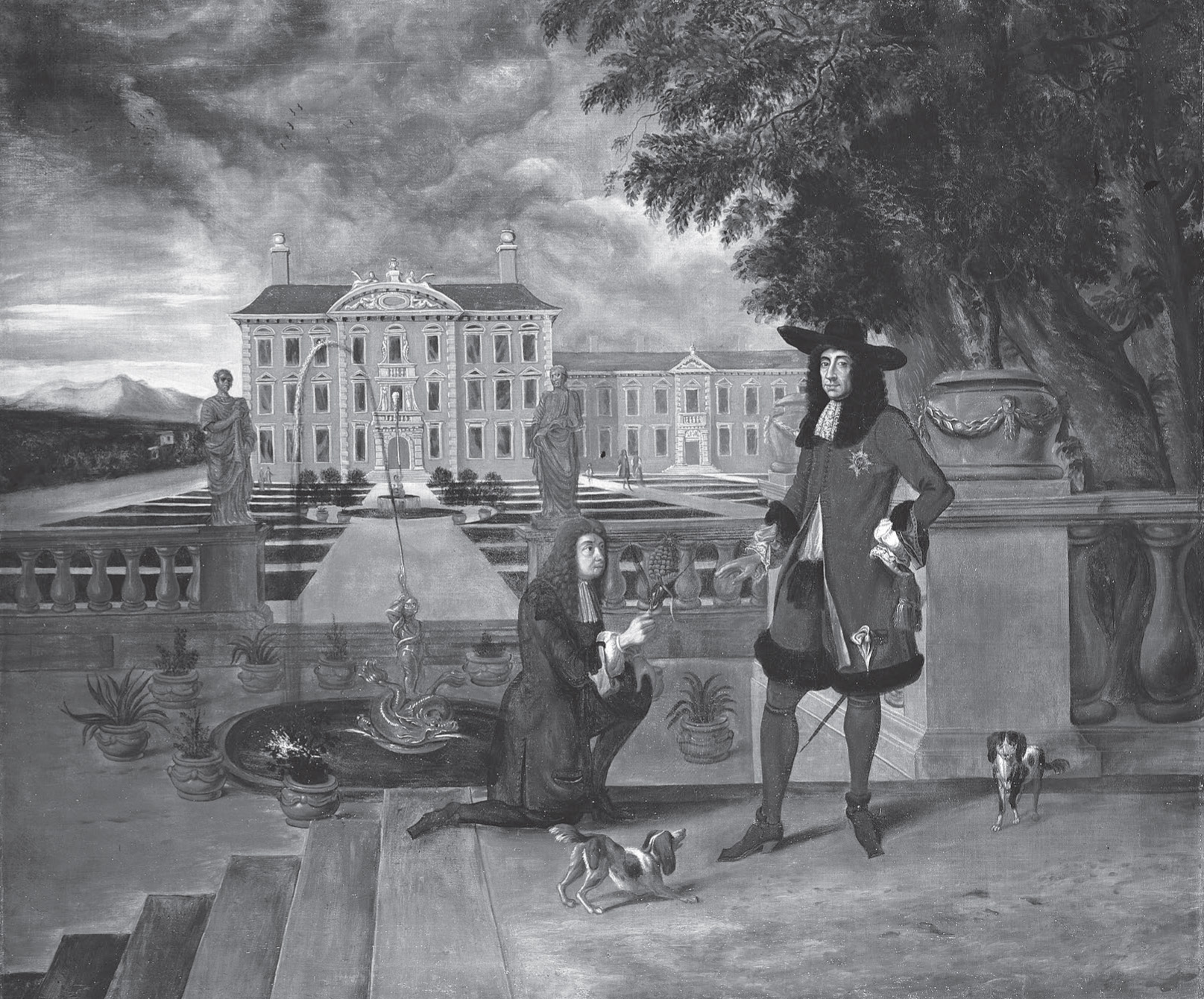

We don’t think we hate cheap things, but we frequently behave as if we do. Consider the pineapple. Columbus was the first European to be delighted by the physical grandeur and vibrant sweetness of the pineapple, which is a native of South America but had reached the Caribbean by the time he arrived there. The first meeting between Europeans and pineapples took place in November 1493, in a Carib village on the island of Guadeloupe. Columbus’s crew spotted the fruit next to a pot of stewing limbs. The outside reminded them of a pine cone, the interior pulp of an apple.

But pineapples proved extremely difficult to transport and very costly to cultivate. For a long time only royalty could actually afford to eat them. Russia’s Catherine the Great was a huge fan, as was Charles II of England. A single fruit in the seventeenth century sold for today’s equivalent of £5,000. The pineapple was such a status symbol that, if they could get hold of one, people would keep it for display until it fell apart. In the mid-eighteenth century, at the height of the pineapple craze, whole aristocratic evenings were structured around the ritual display of these fruits. Poems were written in their honour. Savouring a tiny sliver could be the high point of a year. The pineapple was so exciting and so loved that in 1761 the 4th Earl of Dunmore built a temple on his Scottish estate in its honour. And Christopher Wren had no hesitation in topping the south tower of St Paul’s Cathedral with this evidently divine fruit.

Then, at the very end of the nineteenth century, two things changed. Large commercial plantations of pineapples were established in Hawaii and there were huge advances in steamship technology. Production and transport costs plummeted and, unwittingly, transformed the psychology of pineapple-eating. Today, you can get a pineapple for around £1.50. It still tastes exactly the same, but now the pineapple is one of the world’s least glamorous fruits. It is never served at smart dinner parties and would never be carved on the top of a major civic building.

The pineapple itself has not changed; it is our attitude to it that has. Contemplation of the history of the pineapple suggests a curious overlap between love and economics: when we have to pay a lot for something nice, we appreciate it to the full. Yet as its price in the market falls, passion has a habit of fading away. Naturally, if the object has no merit to begin with, a high price won’t be able to do anything for it; but if it has real virtue and yet a low price, then it is in severe danger of falling into grievous neglect.

Why, then, do we associate a cheap price with lack of value? Our response is a hangover from our long pre-industrial past. For most of human history, there truly was a strong correlation between cost and value: the higher the price, the better things tended to be, because there was simply no way both for prices to be low and for quality to be high. Everything had to be made by hand, by expensively trained artisans, with raw materials that were immensely difficult to transport. The expensive sword, jacket, window or wheelbarrow was simply always the better one. This relationship between price and value held true in an uninterrupted way until the end of the eighteenth century, when – thanks to the Industrial Revolution – something extremely unusual happened: human beings worked out how to make high-quality goods at cheap prices, because of technology and new methods of organizing the labour force.

On the back of this long experience, an entrenched cultural association has formed between the rare, the expensive and the good: each has come to rapidly suggest the other, and the natural-seeming converse is that things which are widely available and inexpensive come to be seen as unimpressive or unexciting.

In principle, industrialization was supposed to undo these connections. The price would fall and widespread happiness would follow. High-quality objects would enter the mass market, excellence would be democratized. However, despite the greatness of these efforts, instead of making wonderful experiences universally available, industrialization has inadvertently produced a different result: it has seemed to rob certain experiences of their loveliness, interest and worth.

It’s not – of course – that we refuse to buy inexpensive or cheap things. It’s just that getting excited over cheap things has come to seem a little bizarre. How do we reverse this? The answer lies in a slightly unexpected area: the mind of a four-year-old. Imagine him with a puddle. It started raining an hour ago, the street is now full of puddles and there could be nothing better in the world; the riches of the Indies would be nothing compared to the pleasures of being able to see the rippling of the water created by a jump in one’s wellingtons, the eddies and whirlpools, the minute waves, the oceans beneath one …

Children have two advantages: they don’t know what they’re supposed to like and they don’t understand money, so price is never a guide to value for them. They have to rely instead on their own delight (or lack of it) in the intrinsic merits of the things they’re presented with and this can take them in astonishing (and sometimes maddening) directions. They’ll spend an hour with one button. We buy them a costly wooden toy made by Swedish artisans who hope to teach lessons in symmetry and find that they prefer the cardboard box that it came in. They become mesmerized by the wonders of turning on the light and therefore proceed to try it 100 times. They’d prefer the nail and screw section of a DIY shop to the fanciest toy department or the national museum.

This attitude allows them to be entranced by objects which have long ago ceased to hold our wonder. If asked to put a price on things, children tend to answer by the utility and charm of an object, not its manufacturing costs. This leads to unusual but – we recognize – more rightful results. A child might guess that a stapler costs £100 and would be deeply surprised, even shocked, to learn that a USB stick can be had for just over £1. Children would be right, if prices were determined by human worth and value, but they’re not; they just reflect what things cost to make. The pity is, therefore, that we treat them as a guide to what matters, when this isn’t what a financial price should ever be used for.

We have been looking at prices the wrong way. We have fetishized them as tokens of intrinsic value, we have allowed them to set how much excitement we are allowed to have in given areas, how much joy is to be mined in particular places. But prices were never meant to be like this: we are breathing too much life into them and thereby dulling too many of our responses to the inexpensive world.

At a certain age, something very debilitating happens to children (normally around the age of eight). They start to learn about ‘expensive’ and ‘cheap’ and absorb the view that the more expensive something is, the better it may be. They are encouraged to think well of saving up pocket money and to see the ‘big’ toy they are given as much better than the ‘cheaper’ one.

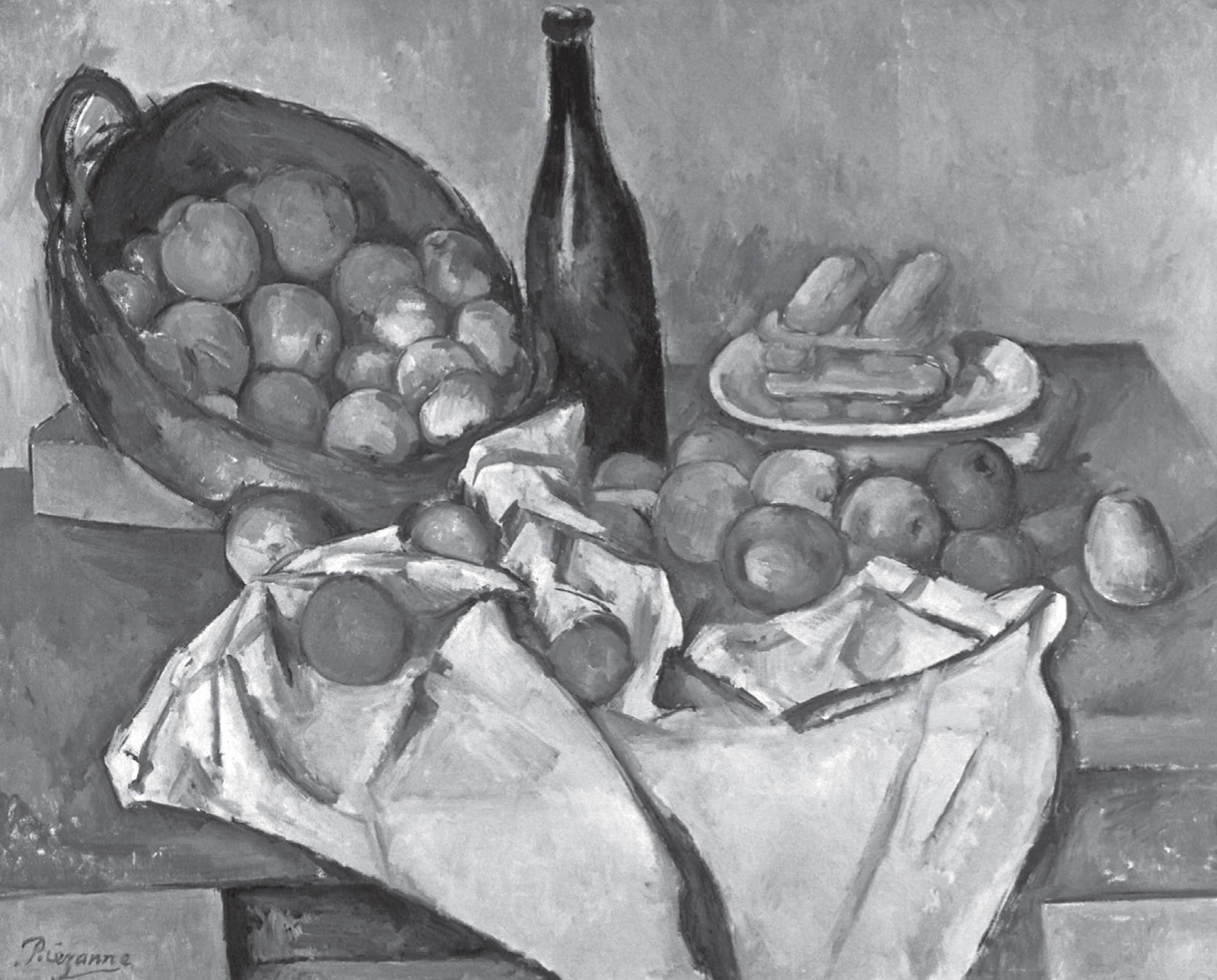

We can’t directly go backwards, we can’t forget what we know of prices. However, we can pay less attention to what things cost and more to our own responses. The people who have most to teach us here are artists. They are the experts at recording and communicating their enthusiasms, which, like children, can take them in slightly unexpected directions. The French artist Paul Cézanne spent a good deal of the late nineteenth century painting groups of apples in his studio in Provence. He was thrilled by their texture, shapes and colours. He loved the transitions between the yellowy golds and the deep reds across their skins. He was an expert at noticing how the generic word ‘apple’ in fact covers an infinity of highly individual examples. Under his gaze, each one becomes its own planet, a veritable universe of distinctive colour and aura – and hence a source of real delight and solace.

The apple that has only a limited life, that will make a slow transition from sweet to sour, that grew patiently on a particular tree, that survived the curiosity of birds and spiders, that weathered the mistral and a particularly blustery May is honoured and properly given its due by the artist (who was himself extremely wealthy, the heir to an enormous banking fortune – it seems important to state this, to make clear that Cézanne wasn’t simply making a virtue of necessity and would have worshipped gold bullion if he’d had the chance). Cézanne had all the awe, love and excitement before the apple that Catherine the Great and Charles II had before the pineapple; but Cézanne’s wonderful discovery was that these elevated and powerful emotions are just as valid in relation to things which can be purchased for the small change in our pockets. Cézanne in his studio was generating his own revolution, not an industrial revolution that would make once-costly objects available to everyone, but a revolution in appreciation, a far deeper process, that would get us to notice what we already have to hand. Instead of reducing prices, he was raising levels of appreciation – which is a move perhaps more precious to us economically because it means we can all access great value with very little money.

Some of what we find ‘moving’ in an encounter with the apples is that we’re restored to a familiar but forgotten attitude of appreciation that we surely once knew in childhood, when we loved the toggles on our rain jackets and found a paper clip a source of fascination and didn’t know what anything cost. Since then life has pushed us into the world of money, where prices loom too large, as we now acknowledge, in our relation to things. While we enjoy Cézanne’s work, it might also unexpectedly make us feel a little sad. That sadness is a recognition of how many of our genuine enthusiasms and loves we’ve had to surrender in the name of the adult world. We’ve perhaps given up on too many of our native loves. The apple is one instance of a whole continent we’ve ceased to marvel at.

Our reluctance to be excited by inexpensive things isn’t a fixed debility of human nature. It’s just a current cultural misfortune. We all naturally used to know the solution as children. The ingredients of the solution are intrinsically familiar. We need to rethink our relationship to prices. The price of something is principally determined by what it cost to make, not how much human value is potentially to be derived from it.

There are two ways to get richer: one is to make more money and the second is to discover that more of the things we could love are already to hand (thanks to the miracles of the Industrial Revolution). We are, astonishingly, already a good deal richer than we’re encouraged to think we are.

IM-PERFECTIONISM

The Netherlands Board of Tourism is responsible for marketing the Dutch countryside. To attract visitors, it employs images of extremely neat windmills bordering pristine canals, with flowers along the banks and permanently sunny skies.

There are occasional places and one or two days of the year – particularly near Leiden in late July – when the Netherlands is exactly like this. But there are many other more typical aspects of the Dutch countryside that the Board of Tourism stays quiet about: it’s almost always overcast, there are many places where there’s not a flower to be seen, it rains most days and there’s always quite a lot of mud. You’ll encounter many a wonky old sluice gate and some rickety palings shoring up the banks. In order to avoid an awkward collision with reality, the Board of Tourism would have been wise to consult a painting in the nation’s main art gallery, the Rijksmuseum, by the seventeenth-century artist Jacob van Ruisdael. Van Ruisdael loved the Dutch countryside, spending as much time there as he could, and he was very keen to let everyone know what he liked about it.

Instead of carefully selecting a special (and unrepresentative) spot and waiting for a rare and fleeting moment of bright sunshine, he adopted a very different ‘selling’ strategy. His most famous painting is an advert for the qualities he discovered. Van Ruisdael loved overcast days and carefully studied the fascinating characteristic movements of stormy skies: he was entranced by the infinite gradations of grey and how one would often see a patch of fluffy white brightness drifting behind a darker, billowing mass of rain-dense clouds. He didn’t deny that there was mud or that the river and canal banks were frequently quite messy. Instead he noticed their special kind of beauty and made a case for it.

The Netherlands Board of Tourism, on the other hand, felt that the reality of what it was selling was unacceptable and so resorted – for the nicest reasons, out of a touching modesty – to lies. But the Dutch countryside is filled with merits: it’s quiet and solemn; it encourages tranquil contemplation; it’s an antidote to stress and forced cheerfulness. These are things we might really need to help us cope with our overloaded and often inauthentic lives.

We should develop the sort of confidence that emerges from understanding a basic fact of human psychology: that we’re all very prepared to accept the less than perfect, if only we can be guided to appreciate it with skill, confidence and charm.

Japanese aesthetics in the early modern period can teach us a great deal about this because it managed to create excitement around things which are, on first hearing, extremely unprepossessing, including moss, weeds, aged houses and – especially – broken pots.

Zen philosophers developed the view that pots, cups and bowls that had become damaged shouldn’t simply be neglected or thrown away. They should continue to attract our respect and attention and be repaired with enormous care, this process symbolizing a reconciliation with the flaws and accidents of time intended to reinforce the underlying themes of Zen. The word given to this tradition of ceramic repair is kintsugi (kin meaning ‘golden’, tsugi ‘joinery’, so literally ‘to join with gold’). In Zen aesthetics, the broken pieces of an accidentally smashed pot should be carefully picked up, reassembled and then glued together with lacquer inflected with a very expensive gold powder. There should be no attempt to disguise the damage; rather, the point is to render the fault lines beautiful and strong. The precious veins of gold are there to emphasize that breaks have a merit all of their own. The origins of kintsugi are said to date to the Muromachi period, when the shogun of Japan, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358–1408), broke his favourite tea bowl and, distraught, sent it to be repaired in China. On its return, he was horrified by the ugly metal staples that had been used to join the broken pieces and charged his craftsmen with devising a more appropriate solution. What they came up with was a method that didn’t disguise the damage, but made something properly artful out of it.

Kintsugi belongs to the Zen ideals of wabi-sabi, which cherishes what is simple, unpretentious and aged – especially if it has a rustic or weathered quality. A story is told of one of the great proponents of wabi-sabi, Sen no Rikyū (1522–91). On a journey through southern Japan, he was once invited to a dinner where the host thought his guest would be impressed by an elaborate and expensive antique tea jar that he had bought from China. But Rikyū didn’t even seem to notice this item and instead spent his time chatting and admiring a branch swaying in the breeze outside. In despair at this lack of interest, once Rikyū had left, the devastated host smashed the jar to pieces and retired to his room. But the other guests more wisely gathered the fragments and stuck them together using kintsugi. When Rikyū next came to visit, he turned to the repaired jar and, with a knowing smile, exclaimed, ‘Now it is magnificent.’

Concepts like kintsugi provide case studies that teach us a useful kind of confidence. Things that might easily be thought unworthy of appreciation can, if described in the right way, emerge as deeply worth valuing.

SOLACE

The greatest share of all the art that humans have ever made for one another has had one thing in common: it has dealt, in one form or another, with sorrow. Unhappy love, poverty, discrimination, anxiety, sexual humiliation, rivalry, regret, shame, isolation and longing – these have been the chief constituents of art down the ages.

However, in public discussion we are often unhelpfully coy about the extent of our grief. The chat tends to be upbeat or glib; we are under awesome pressure to keep smiling in order not to shock, provide ammunition for enemies or sap the energy of the vulnerable. We therefore end up not only sad, but sad that we are sad – without much public confirmation of the essential normality of our melancholy. We grow harmfully buttoned up or convinced of the desperate uniqueness of our fate.

All this culture can correct, standing as a record of the tears of humanity, lending legitimacy to despair and replaying our miseries back to us with dignity, shorn of many of their haphazard or trivial particulars. ‘A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us,’ proposed Kafka (though the same could be said of any art form) – in other words, art is a tool that can help release us from our numbness and provide for catharsis in areas where we have for too long been wrong-headedly brave.

Such pessimism is also a corrective to prevailing sentimentality. It provides an acknowledgement that we are inherently flawed creatures, incapable of lasting happiness, beset by troubling sexual desires, obsessed by status, vulnerable to appalling accidents and always – slowly – dying.

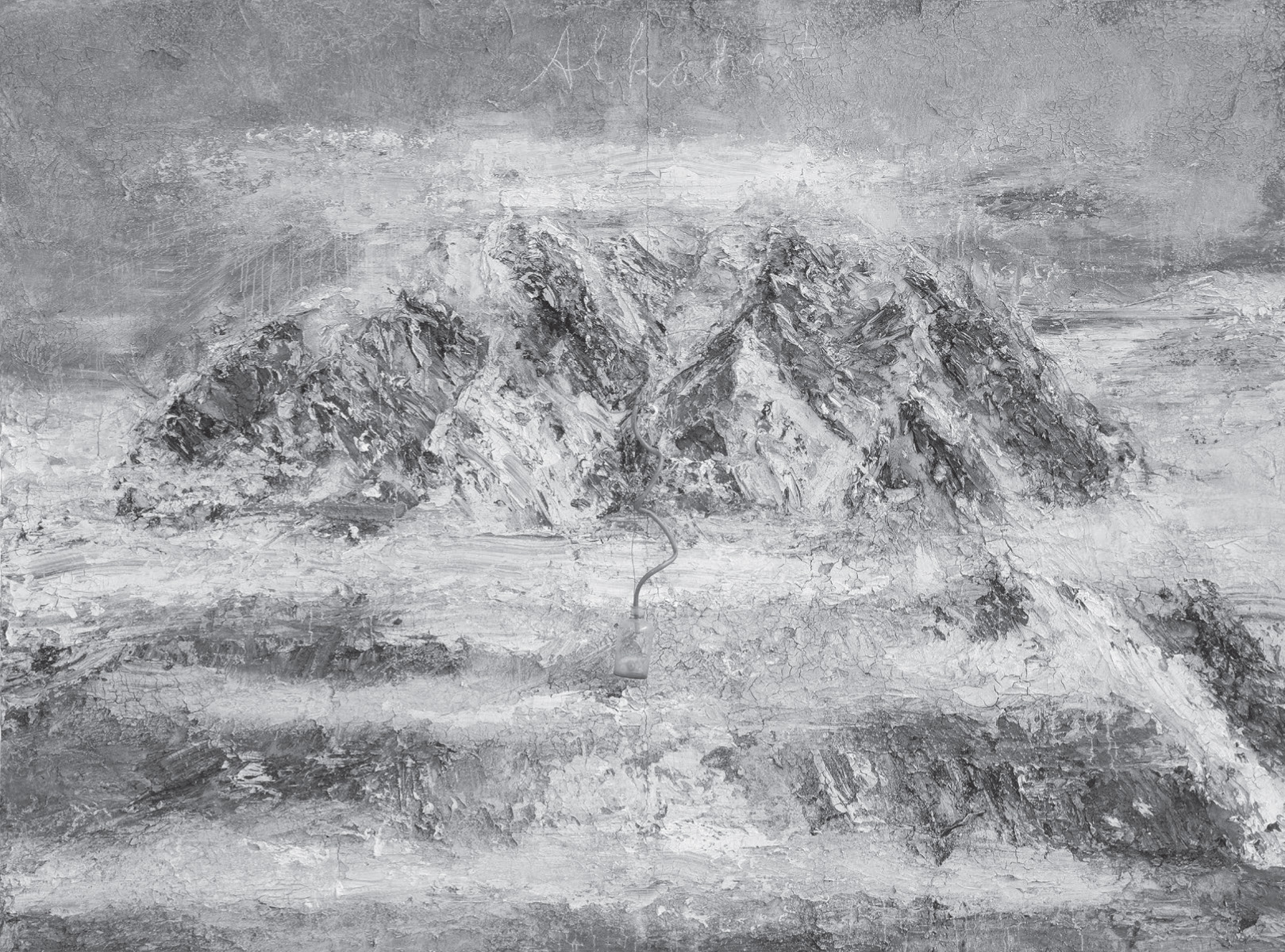

The German artist Anselm Kiefer is – running counter to the normal habits of our society – extremely forthright about the essentially sorrowful character of the human condition. Everything we love and care about will come to ruin; all that we put our hope in will fail. In a note accompanying his vast painting Alkahest, which is nearly four metres across, Kiefer writes that even ‘rock that looks as though it will last for ever is dissolved, crushed to sand and mud’. The dramatic scale is not accidental. It’s a way of trying to make obvious something that is often repressed and ignored: that dejection, sadness and disappointment are major parts of being human. The work’s icy, grey, harsh character summons up equally grim thoughts about our own lives.

It’s not an intimate picture because the fact Kiefer is asserting isn’t a personal one. He’s not attempting to delve into the unique painful details of our individual sorrows. The painting isn’t about a relationship that didn’t work out, a friendship that went wrong, a dead parent we never fully made peace with, a career choice that led to wasted years. Instead it sums up a feeling and an attitude: lonely, lost, cold, worried, frightened. And instead of denouncing these feelings as worthy only of losers, the work proclaims them as important, serious and worthy. It is as if the picture is beaming out a collective message: ‘I understand, I know, I feel the same as you do, you are not alone.’ Our own private failings and woes – which may strike us as sordid or shameful or very much our own fault – are transformed; they are now a manifestation of the tragic theme of existence, which is everywhere and immutable. They are, in fact, ennobled, by their kinship to this grand work. It is like the way a national anthem works: by singing it, the individual feels part of a greater community and is strengthened, given confidence, even feeling strangely heroic, irrespective of their circumstances. Kiefer’s work is like a visual anthem for sorrow, one that invites us to see ourselves as part of the nation of sufferers, which includes, in fact, everyone who has ever lived.

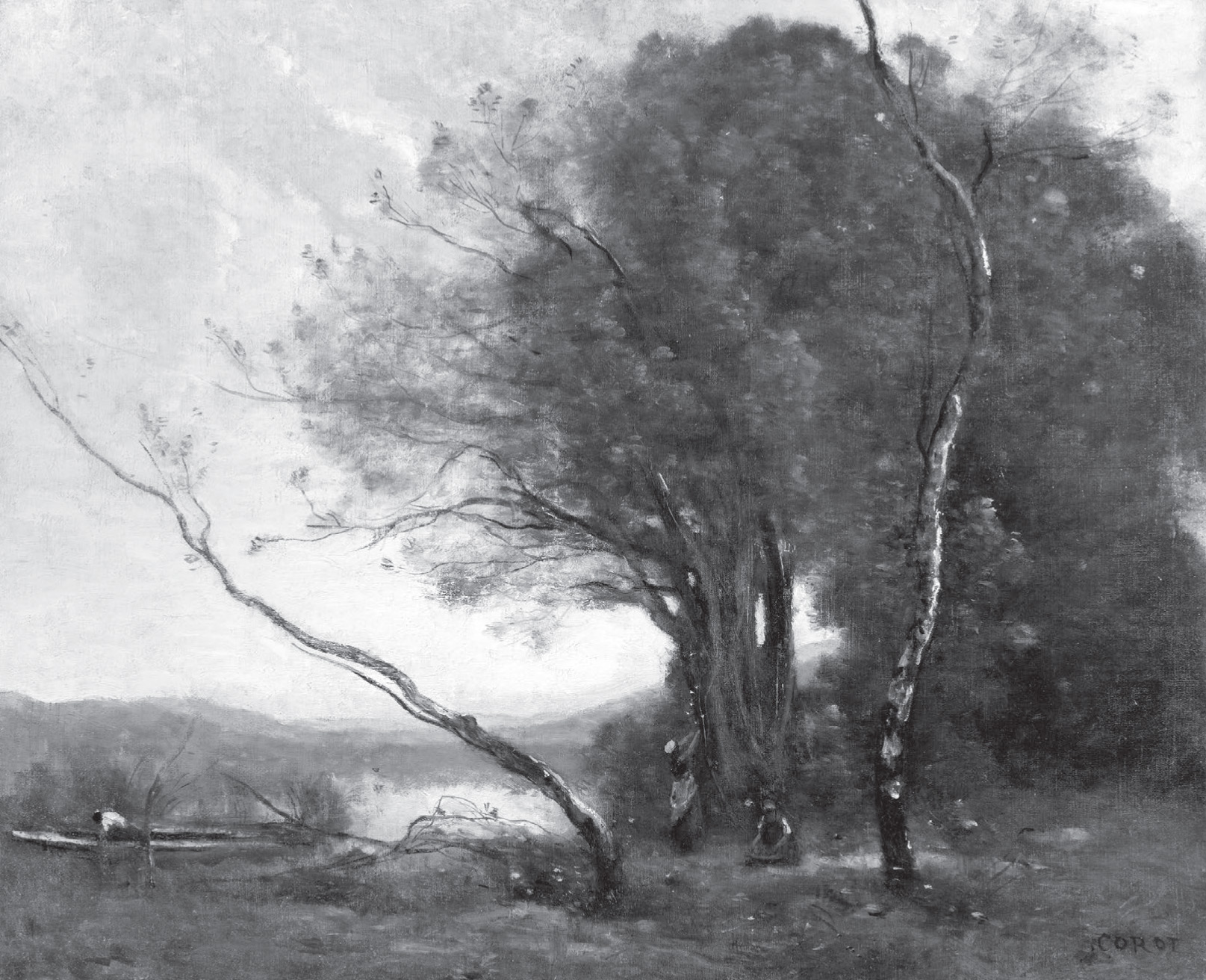

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot described his painting The Leaning Tree Trunk as a souvenir or memory. It is filled with the idea of farewell. The moment will pass, light will fade, night will fall – the years will pass and we will wonder what we did with them. Corot was in his sixties when he painted this work: the mood is elegiac, mourning what has gone and will never come back. Ultimately, it is a farewell to life, but it is not a bitter or desperate one. The mood is resigned, dignified and, although sad, accepting. Our own personal grief at the passing of our life (if not soon, then some day – but always too soon) is set within a much wider context. A tree grows, is bent and twisted by fate, like the one in the background, and eventually dries up and withers, like the one in the foreground. The sunlight illuminates the sky for a while and is then hidden behind the clouds and night descends. We are part of nature. Corot isn’t glad that the day is over, that the years have gone and that the tree is dying, but his painting seeks to instil a mood of sad yet tranquil acceptance of our own share in the fate of all living things.

This is a proposition we encounter repeatedly in the arts: other people have had the same sorrows and troubles that we have; it isn’t that these don’t matter or that we shouldn’t have them or that they aren’t worth bothering about. What counts is how we perceive them. We encounter the spirit or voice of someone who profoundly sympathizes with suffering, but who allows us to sense that through it we’re connecting with something universal and unashamed. We are not robbed of our dignity; we are discovering the deepest truths about being human – and therefore we are not only not degraded by sorrow but also, strangely, elevated.

We can imagine ourselves as a series of concentric circles. On the outside lie all the more obvious things about us: what we do for a living, our age, education, tastes in food and broad social background. We can usually find plenty of people who recognize us at this level. But deeper in are the circles that contain our more intimate selves, involving feelings about parents, secret fears, daydreams, ambitions that might never be realized, the stranger recesses of our sexual imagination and all that we find beautiful and moving.

Though we may long to share the inner circles, too often we seem able only to hover with others around the outer ones, returning home from yet another social gathering with the most sincere parts of us aching for recognition and companionship. Traditionally, religion provided an ideal explanation for and solution to this painful loneliness. The human soul, religious people would say, is made by God and so only God can know its deepest secrets. We are never truly alone, because God is always with us. In their way, religions addressed a universal problem: they recognized the powerful need to be intimately known and appreciated and admitted frankly that this need could not realistically ever be met by other people.

What replaced religion in our imaginations, as we have seen, is the cult of human-to-human love we now know as Romanticism, which bequeathed to us the beautiful but reckless idea that loneliness might be capable of being vanquished, if we are fortunate and determined enough to meet the one exalted being known as our soulmate, someone who will understand everything deep and strange about us, who will see us completely and be enchanted by our totality. But the legacy of Romanticism has been an epidemic of loneliness, as we are repeatedly brought up against the truth: the radical inability of any one other person to wholly grasp who we truly are.

Yet there remains, besides the promises of love and religion, one other – and more solid – resource with which to address our loneliness: culture.

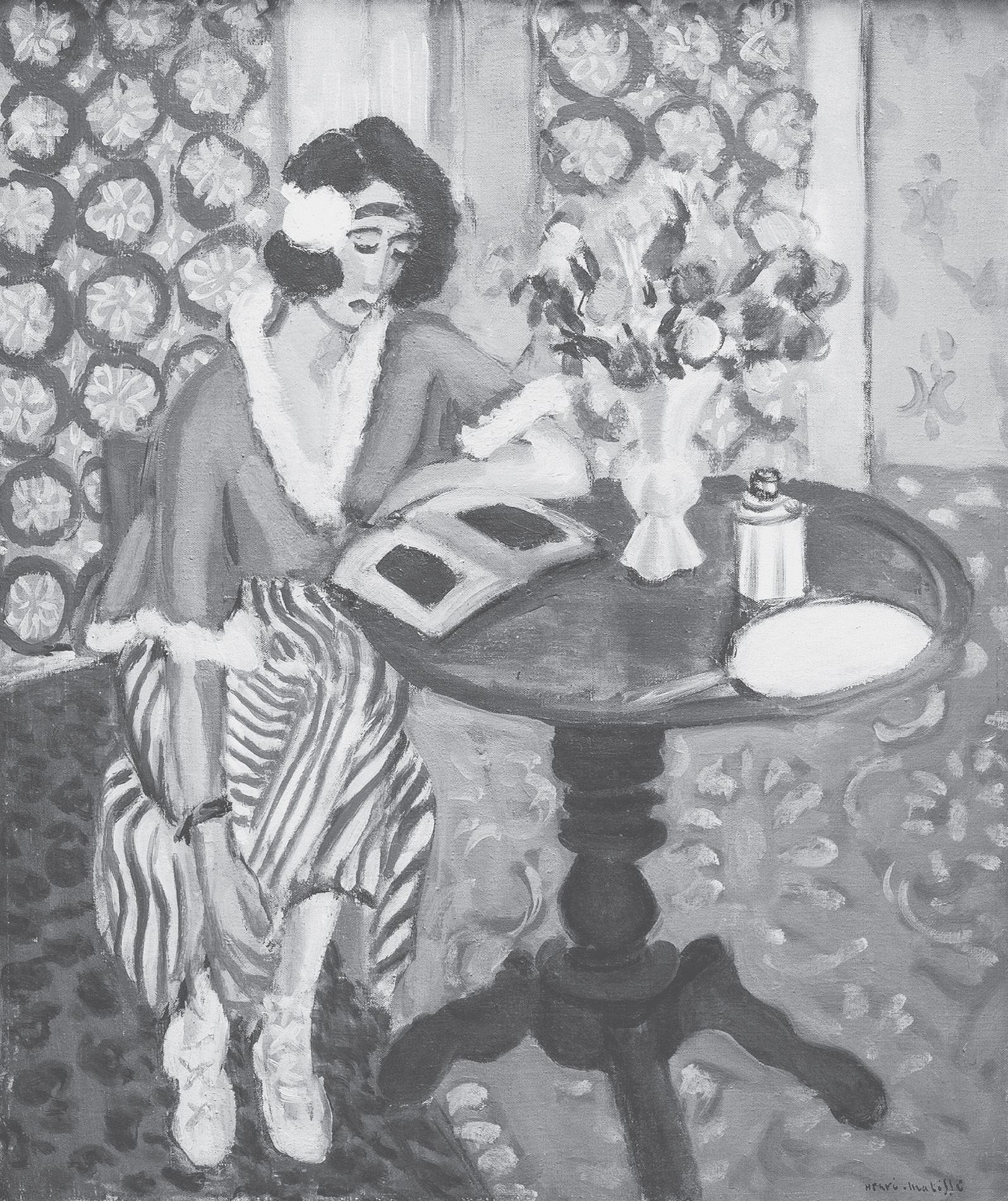

Henri Matisse began painting people reading from his early twenties and continued to do so throughout his life; at least thirty of his canvases tackle the theme. What gives these images their poignancy is that we recognize them as records of loneliness that has at least in part been redeemed through culture. The figures may be on their own, their gaze often distant and melancholy, but they have to hand perhaps the best possible replacement when the immediate community has let us down: books.

The English psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, working in the middle years of the twentieth century, was fascinated by how certain children coped with the absence of their parents. He identified the use of what he called ‘transitional objects’ to keep the memory of parental love strong even when the parents weren’t there. So a teddy bear or a blanket, he realized, could be a mechanism for activating the memory of being cared for, a mechanism that is usefully mobile and portable and is always accessible when the parents are at bay.

Winnicott proposed that works of art can, for adults, function as more sophisticated versions of just these kinds of transitional objects. What we are at heart looking for in friendship is not necessarily someone we can touch and see in front of us, but a person who shares, and can help us develop, our sensibility and values, someone to whom we can turn and look for a sign that they too feel what we have felt, that they are attracted, amused and repulsed by similar things. And, strangely, it appears that certain imaginary friends drawn from culture can end up feeling more real and in that sense more present to us than any of our real-life acquaintances, even if they have been dead a few centuries and lived on another continent. We can feel honoured to count them among our best friends.

Christen Købke lived in and around Copenhagen in the first half of the nineteenth century (he died of pneumonia in his late thirties in 1848), yet we might count him among our closest friends because of his sensitivity to just the sort of everyday beauty we are deeply fond of but that gets very little mention in the social circles around us. From a great distance, Købke acts like an ideal companion who gently works his way into the quiet, hidden parts of us and helps them grow in strength and self-awareness.

The arts provide a miraculous mechanism whereby a total stranger can offer us many of the things that lie at the core of friendship. And when we find these art friends, we are unpicking the experience of loneliness. We’re finding intimacy at a distance. The arts allow us to become the soulmates of people who, despite having been born in 1630 or 1808, are, in limited but crucial ways, our proper companions. The friendship may even be deeper than that we could have enjoyed in person, for it is spared all the normal compromises that attend social interactions. Our cultural friends can’t converse fully, of course, and we can’t reply (except in our imagination). And yet they travel into the same psychological space, at least in some key respects, as we are in at our most vulnerable and intimate points. They may not know of our latest technology, they have no idea of our families or jobs, but in areas that really matter to us they understand us to a degree that is at once a little shocking and deeply thrilling.

Confronted by the many failings of our real-life communities, culture gives us the option of assembling a tribe for ourselves, drawing their members across the widest ranges of time and space, blending some living friends with some dead authors, architects, musicians and composers, painters and poets.

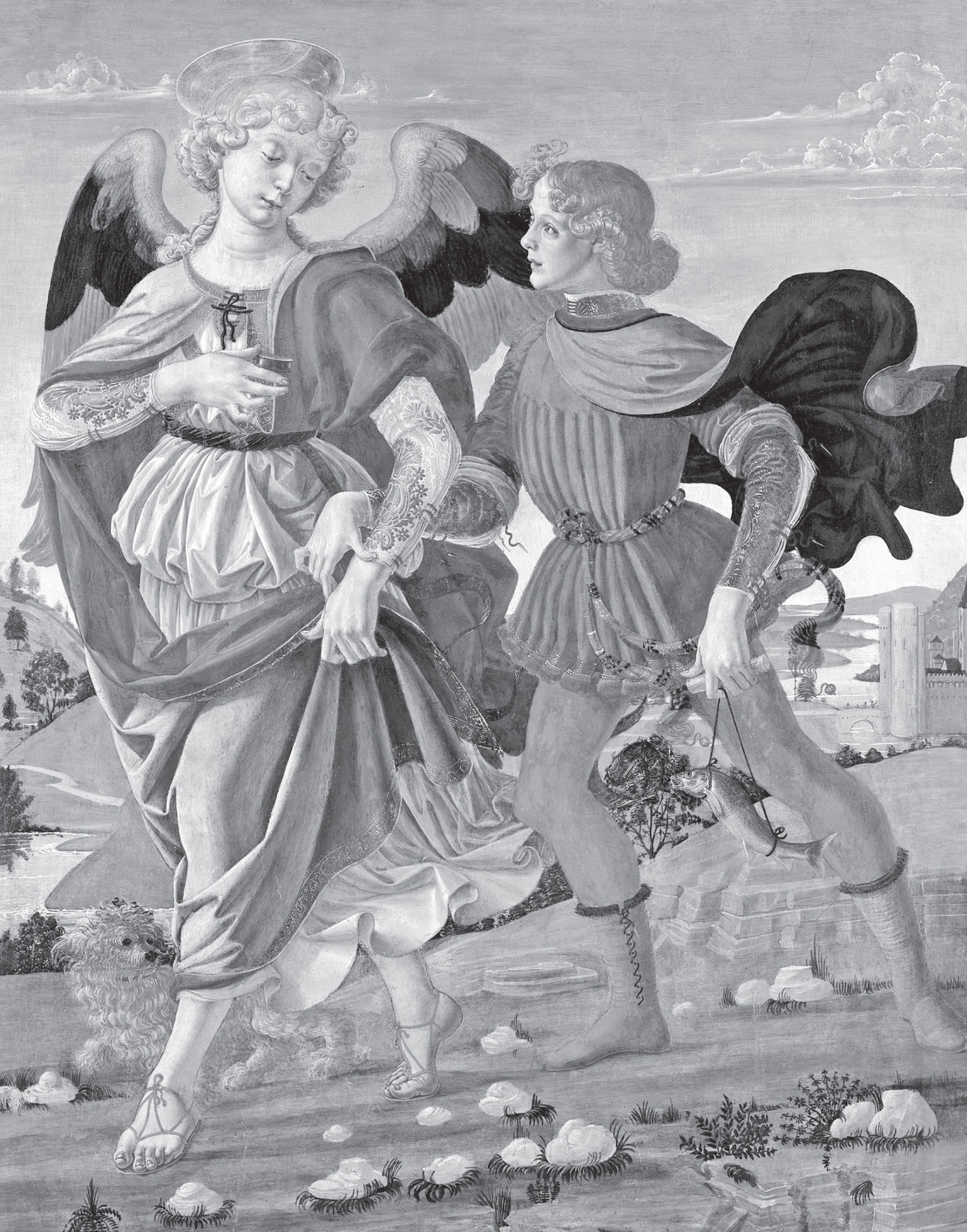

The fifteenth-century Italian painter Andrea del Verrocchio – one of whose apprentices was Leonardo da Vinci – was deeply attracted to the Bible story of Tobias and the Angel. It tells of a young man, Tobias, who has to go on a long and dangerous journey. But he has two companions: one a little dog, the other an angel who comes to walk by his side, advise him, encourage him and guard him.

The old religious idea was that we are never fully alone; there are always special beings around us upon whose aid we can call. Verrocchio’s picture is touching not because it shows a real solution we can count on, but because it points to the kind of companionship we would love to have and yet normally don’t feel we can find.

Yet there is an available version. Not, of course, in the form of winged creatures with golden halos round their heads. But rather the imaginary friends that we can call on from the arts. You might feel physically isolated in the car, hanging around at the airport, going into a difficult meeting, having supper alone yet again or going through a tricky phase in a relationship, but you are not psychologically alone. Key figures from your imaginary tribe (the modern version of angels and saints) are with you: their perspective, their habits, their ways of looking at things are in your mind, just as if they were really by your side whispering in your ear. And so we can confront the difficult stretches of existence not simply on the basis of our own small resources but accompanied by the accumulated wisdom of the kindest, most intelligent voices of all ages.

Given the enormous role of sadness in our lives, it is one of the greatest emotional skills to know how to arrange around us those cultural works that can best help to turn our panic or sense of persecution into consolation and nurture.

GOOD ENOUGH

High ambitions are noble and important, but there’s also a point when they become the sources of terrible trouble and unnecessary panic.

One way of undercutting our more reckless ideals and perfectionism was pioneered by Donald Winnicott in the 1950s. Winnicott specialized in relationships between parents and children. In his clinical practice, he often met with parents who felt like failures: perhaps because their children hadn’t got into the best schools, or because there were sometimes arguments around the dinner table or the house wasn’t always completely tidy.

Winnicott’s crucial insight was that the parents’ agony was coming from a particular place: excessive hope. Their despair was a consequence of a cruel and counterproductive perfectionism. To help them reduce this, Winnicott developed a charming phrase: ‘the good enough parent’. No child, he insisted, needs an ideal parent. They just need an OK, pretty decent, usually well-intentioned, sometimes grumpy but basically reasonable father or mother. Winnicott wasn’t saying this because he liked to settle for second best, but because he knew the toll exacted by perfectionism, and realized that in order to remain more or less sane (which is a very big ambition already) we have to learn not to hate ourselves for failing to be what no ordinary human being ever really is anyway.

The concept of ‘good enough’ was invented as an escape from dangerous ideals. It began in relation to parenthood, but it can be applied across life more generally, especially around work and love.

A relationship may be good enough even while it has its very dark moments. Perhaps at times there’s little sex and a lot of heavy arguments. Maybe there are big areas of loneliness and non-communication. Yet none of this should lead us to feel freakish or unnaturally unlucky. It can be good enough.

Similarly, a good-enough job will be very boring at points, it won’t perfectly utilize all our merits or pay a fortune. But we may make some real friends, have times of genuine excitement and finish many days tired but with a sense of true accomplishment.

It takes a great deal of bravery and skill to keep even a very ordinary life going. To persevere through the challenges of love, work and children is quietly heroic. We should perhaps more often sometimes step back in order to acknowledge in a non-starry-eyed but very real way that our lives are good enough – and that this is, in itself, already a very impressive achievement.

GRATITUDE

The standard habit of the mind is to take careful note of what’s not right in our lives and obsess about all that is missing. But in a new mood, perhaps after a lot of longing and turmoil, we pause and notice some of what has – remarkably – not gone wrong. The house is looking beautiful at the moment. We’re in pretty good health, all things considered. The afternoon sun is deeply reassuring. Sometimes the children are kind. Our partner is – at points – very generous. It’s been quite mild lately. Yesterday, we were happy all evening. We’re quite enjoying our work at the moment.

Gratitude is a mood that grows with age. It is extremely rare to delight in flowers or a quiet evening at home, a cup of tea or a walk in the woods when one is under twenty-two. There are so many larger, grander things to be concerned about: romantic love, career fulfilment and political change. However, it is rare to be left entirely indifferent by smaller things in time. Gradually, almost all one’s earlier, larger aspirations take a hit, perhaps a very large hit. One encounters some of the intractable problems of intimate relationships. One suffers the gap between one’s professional hopes and the available realities. One has a chance to observe how slowly and fitfully the world ever alters in a positive direction. One is fully inducted into the extent of human wickedness and folly – and into one’s own eccentricity, selfishness and madness.

And so ‘little things’ start to seem somewhat different: no longer a petty distraction from a mighty destiny, no longer an insult to ambition, but a genuine pleasure amid a litany of troubles, an invitation to bracket anxieties and keep self-criticism at bay, a small resting place for hope in a sea of disappointment. We appreciate the slice of toast, the friendly encounter, the long hot bath, the spring morning – and properly keep in mind how much worse it could, and probably will one day, be.

WISDOM

To teach us how to be wise is the underlying central purpose of philosophy. The word may sound abstract and lofty, but wisdom is something we might plausibly aim to acquire a little more of over the course of our lives, even if true wisdom requires that we always keep in mind the persistent risk of madness and error.

Wisdom can be said to comprise twelve ingredients.

Realism

The wise are, first and foremost, ‘realistic’ about how challenging many things can be. They are fully conscious of the complexities entailed in any project: for example, raising a child, starting a business, spending an agreeable weekend with the family, changing the nation, falling in love … Knowing that something difficult is being attempted doesn’t rob the wise of ambition, but it makes them more steadfast, calmer and less prone to panic about the problems that will invariably come their way. The wise rarely expect anything to be wholly easy or to go entirely well.

Appreciation

Properly aware that much can and will go wrong, the wise are unusually alive to moments of calm and beauty, even extremely modest ones, of the kind that those with grander plans rush past. With the dangers and tragedies of existence firmly in mind, they can take pleasure in a single, uneventful sunny day, or some pretty flowers growing by a brick wall, the charm of a three-year-old playing in a garden or an evening of intimate conversation among friends. It isn’t that they are sentimental and naive; in fact, precisely the opposite. Because they have seen how hard things can get, they know how to draw the full value from the peaceful and the sweet – whenever and wherever these arise.

Folly

The wise know that all human beings, themselves included, are never far from folly. They have irrational desires and incompatible aims, they are unaware of a lot of what they feel, they are prone to mood swings, they are visited by powerful fantasies and delusions – and are always buffeted by the curious demands of their sexuality. The wise are unsurprised by the ongoing coexistence of deep immaturity and perversity alongside quite adult qualities like intelligence and morality. They know that we are barely evolved apes. Aware that at least half of life is irrational, they try – wherever possible – to budget for madness and are slow to panic when it (reliably) rears its head.

Humour

The wise take the business of laughing at themselves seriously. They hedge their pronouncements and are sceptical in their conclusions. Their certainties are not as brittle as those of others. They laugh from the constant collisions between the noble way they’d like things to be and the demented way they in fact often turn out.

Politeness

The wise are realistic about social relations, in particular about how difficult it is to change people’s minds and have an effect on their lives. They are therefore extremely reticent about telling others too frankly what they think. They have a sense of how seldom it is useful to get censorious with others. They want, above all, things to be nice in social settings, even if this means they are not totally authentic. So they will sit with someone of an opposite political persuasion and not try to convert them; they will hold their tongue with someone who seems to be announcing a wrong-headed plan for reforming the country, educating their child or directing their personal life. They’ll be aware of how differently things can look through the eyes of others and will search more for what people have in common than for what separates them.

Self-Acceptance

The wise have made their peace with the yawning gap between how they would ideally want to be and what they are actually like. They have come to terms with their tendencies to idiocy, ugliness and error. They are not fundamentally ashamed of themselves because they have already shed so much of their pride.

Forgiveness

The wise are comparably realistic about other people. They recognize the extraordinary pressure everyone is under to pursue their own ambitions, defend their own interests and seek their own pleasures. It can make others appear extremely mean and purposefully evil, but this would be to overpersonalize the issue. The wise know that most hurt is not intentional but a by-product of the constant collision of blind competing egos in a world of scarce resources.

The wise are therefore slow to anger and judge. They don’t leap to the worst conclusions about what is going on in the minds of others. They will be readier to overlook a hurt from a proper sense of how difficult every life is, harbouring as it does so many frustrated ambitions, disappointments and longings. Of course they shouted, of course they were rude, of course they wanted to appear slightly more important … The wise are generous as to the reasons why people might not be nice. They feel less persecuted by the aggression and meanness of others, because they have a sense of the place of hurt these feelings come from.

Resilience

The wise have a solid sense of what they can survive. They know just how much can go wrong and things will still be – just about – liveable. The unwise person draws the boundaries of their contentment far too far out, so that it encompasses, and depends upon, fame, money, personal relationships, popularity, health … The wise person sees the advantages of all of these, but also knows that they may – before too long, at a time of fate’s choosing – have to draw the borders right back and find contentment within a more confined space.

Envy

The wise don’t envy idly, realizing that there are some good reasons why they don’t have many of the things they really want. They look at the tycoon or the star and have a decent grasp of why they weren’t able to succeed at this level. It seems like just an accident, an unfair one, but there were in fact some logical reasons.

At the same time, the wise see that some destinies are truly shaped by nothing more than accident. Some people are promoted randomly. Companies that aren’t especially deserving can suddenly make it big. Some people have the right parents. The winners aren’t all noble and good. The wise appreciate the role of luck and don’t curse themselves overly at those junctures where they have evidently not had as much of it as they would have liked.

Success and Failure

The wise emerge as realistic about the consequences of winning and succeeding. They may want to win as much as the next person, but they are aware of how many fundamentals will remain unchanged, whatever the outcome. They don’t exaggerate the transformations available to us. They know how much we remain tethered to some basic dynamics in our personalities, whatever job we have or material possession we acquire. This is both cautionary (for those who succeed) and hopeful (for those who won’t). The wise see the continuities between the two categories overemphasized by modern consumer capitalism: success and failure.

Regrets

In our ambitious age, it is common to begin with dreams of being able to pull off an unblemished life, where one can hope to get the major decisions, in love and work, right. But the wise realize that it is impossible to fashion a spotless life. We will make some extremely large and utterly uncorrectable errors in a number of areas. Perfectionism is a wicked illusion. Regret is unavoidable.

But regret lessens the more we see that error is endemic across the species. We can’t look at anyone’s life story without seeing some devastating mistakes etched across it. These errors are not coincidental but structural. They arise because we all lack the information we need to make choices in time-sensitive situations. We are all, where it counts, steering almost blind.

Calm

The wise know that turmoil is always around the corner – and they have come to fear and sense its approach. That’s why they nurture such a strong commitment to calm. A quiet evening feels like an achievement. A day without anxiety is something to be celebrated. They are not afraid of having a somewhat boring time. There could, and will again, be so much worse.

And, finally, of course, the wise know that it will never be possible to be wise every hour, let alone every day, of their lives.