In 1877 Alfred Baldwin took the plunge and formally moved over to the Conservatives.1 He had never been a particular supporter of Gladstone, rather a slightly Whiggish Palmerstonian. Over the next decade he moved effortlessly into the heart of the landed families who ran the Conservative Party, becoming a Justice of the Peace in 1879, and an active and valued member of the Worcestershire Conservative executive and other regional and national associations. He was instrumental in renewing the party’s local organization after the many electoral reforms of the period. Two major events had precipitated his break with the political party his family had supported so steadily. The political motive was what became known as the Eastern Question. The moral impetus was the radical pressure for Church disestablishment.

The Eastern Question began to preoccupy the minds of Britons in the summer of 1874. A Russo-Turkish treaty permitted Russia (Britain’s traditional enemy) to approach the Sublime Porte, or Ottoman government, on behalf of Russian Orthodox Christians living under Ottoman jurisdiction. The British, always on the alert for signs of expansionism, saw this as one more attempt to spread Russia’s power and influence. Then several waves of Balkan uprisings, which led either to severe repression or to appalling atrocities by the Turks (depending on your political viewpoint), brought the question to ignition point. The Treaty of San Stefano, signed at the end of the ensuing Russo-Turkish war (1877–8), was thought by many to be inadequate to protect British interests in the region. Gladstone felt that the solution lay not in supporting Russia or Turkey, but in promoting autonomous rule to the people of the Balkans. Many in Britain, including Alfred, felt that, by not supporting Turkey, Gladstone was by default supporting Russia.*

Burne-Jones, on the other hand, was passionately with Gladstone over his stand on the Eastern Question. It was the first (and last) time he was to become personally involved in political agitation. While it lasted he was totally committed. Gladstone gathered most of his support from the intelligentsia and the Nonconformists, seeing the matter as a moral rather than a political one. In 1876 the Eastern Question Association had been formed to ensure the dissemination of information for the cause. Morris became treasurer of the association, and Howard and Burne-Jones joined in, together with more political types – Carlyle and the MP John Bright among them. That year Burne-Jones helped convene a conference at St James’s Hall, where Gladstone spoke; in 1878 he continued his involvement, organizing with Morris and Crom Price a Workmen’s Neutrality Demonstration at Exeter Hall to discuss the same question. In 1882 he was instrumental in getting the government to take action on reports of systematic persecution of the Jews that were starting to come in from Eastern Europe. But by this time Burne-Jones was becoming disillusioned – the amount of time and energy it took to create the smallest change in public perception, much less in government policy, was overwhelming. He took this personally, and could not accept the equanimity with which the government could oversee what he understood as injustice and cruelty. Morris relished his first immersion into politics and began to become seriously involved with the socialist movement. At this Burne-Jones drew back – by 1890 he was so detached that he was fined for refusing to do jury service. He said, ‘I have no politics, and no party, and no particular hope: only this is true, that beauty is very beautiful, and softens, and comforts, and inspires, and rouses, and lifts up, and never fails.’3

Georgie was with him in his earlier political forays, getting passionately involved herself. Over time, however, their attitudes revealed their essential differences in character. Burne-Jones became progressively disenchanted with the political world: Georgie was a sticker, and remained faithful to her initial enthusiasm always. In addition, Burne-Jones was to move steadily rightward, while Georgie remained a proud socialist to the end of her days. Louie, on the other hand, showed no interest in politics at the beginning, and it would appear that Alfred’s initial withdrawal from politics had much to do with his marriage in its early days. After he returned to the fray, Louie retired to bed; it was only after her son was grown that she recovered enough to take an interest, as the wife of a Conservative stalwart.

Alfred saw Gladstone and the Liberal Party’s policy on the Balkans as a betrayal. When some Liberals also began to work towards separating the Church of England from the governance of the state, it was one step too far. Alfred could not contemplate this, and could stay with the Liberals no longer, distrusting their ‘infidelity’ as well as their ‘socialism’. His break with the Liberals over Church reform is important in understanding his character. Louie and Alfred were the two members of the family who continued to be regular communicants, for whom religion was at the core of their beings. Lockwood, on his branch of the family’s church-going, simply said, ‘None of us, by the way, ever go.’4 Later, in an attempt at fiction, he elaborated:

I have knelt with my brow pressed against the back of a rush-bottomed chair in ritualistic Churches in England. I have bowed my head in baize-lined pews of Dissent; I have knelt at the amateur prayer-meetings of those evangelical ladies and gentlemen who proposed to ‘unite in prayer’ as godless people propose ‘to have a little music’ or a hand at whist … I have marvelled at the ravings of methodist ranters round weeping and snuffling victims at the ‘penitent bench’.5

Georgie was crisper: ‘Going to church seems to me so poor a substitute for religion.’6 This was shorthand. Art had been her religion from adolescence, while she maintained a strong core of orthodox belief. She wrote a condolence letter to a friend who had lost his sister:

I cannot write or feel sadly about her death any more than I could about her life, for the one is part of the other to me and I am sure was not different so far as you could see … year by year I feel more certainty of life beyond.7

Burne-Jones felt the same way, although he expressed it differently:

There was a Samoan chief once whom a missionary was bullying. Said the missionary: ‘But have you, my dear sir, no conception of a deity?’ Said the Samoan chief: ‘We know that at night-time someone goes by amongst the trees, but we never speak of it.’ They dined on the missionary that same day, but he tasted so nasty that they gave up eating people ever after, so he did some good after all …

When Burne-Jones was asked about his beliefs, he just repeated the words of the Samoan: ‘We know that at night-time someone goes by amongst the trees, but we never speak about it.’8

Alfred and Louie, on the other hand, not only spoke about their beliefs, they acted on them. In 1878 Alfred set up a local Sunday school. In 1879 he laid the foundation stone for a new church at Wilden, to be called All Saints. He financed it in the main, and was its first churchwarden.* He tithed his income to the church, and gave substantially to charity. Alfred had left the Nonconformism of his family in his early twenties, and by the time he married he described himself as ‘high church’. It was not that he was extreme, just that he had come a long way from the low, almost Dissenting, Church of his childhood. Rather than being attached to the high Anglicanism of the Oxford movement, he was convinced that the traditions of the Church of England, its position as the ‘national’ Church in the unity of the nation, were what was important.

In addition, faith as part of daily routine sustained Alfred. Until his death he professed himself a disciple of Charles Kingsley, who believed that religion and secular pursuits were not separate, and that both together made up a full Christian life.10 It is in this world, not the next, that the Christian man engages and struggles with God’s purposes. Alfred was a wholehearted admirer of these ideas, ‘exalt[ing] practice over theory’, ‘in the world … [but not] of the world’. Duty was the important point. A man had to work because it was his duty to do so, serving God and his fellow men by performing his job to the best of his ability. It was a religious and ethical, as well as social, necessity. Success was given to man by God, and it was man’s moral obligation to serve God well by using his wealth and position for the greater good of his fellows.

This makes Alfred seem to some modern eyes to be rather a dreary character, although contemporary accounts show that he was clearly much loved, as well as greatly respected. He drove his family firm forward without the ruthlessness of the great capitalists. He knew all his workers personally. He was patriarchal, but in the sense that his workers were an extended family, ‘that the connection between master and servant should be something beyond one of mere cash and that a master’s interest did not cease when he had paid his workers on Saturday night’. He was the first Midlands ironmaster to allow his workers eight-hour shifts, instead of the standard twelve-hour day. Safety, hygiene, housing, medical care, guaranteed employment – all were part of the duties Alfred saw as his.

Louie was the wife of the owner, and as such, when her health allowed it, carried out her role: exemplar to the women of the community. As well as a church and a Sunday school, Alfred built a school for the children of his employees; Louie and Edie (and later Stan) lectured and taught at the Sunday school and at the various groups and societies set up for worker improvement – works bodies and also a ‘friendly society’, which organized, on a voluntary basis, mutual insurance for the workers.* Family events were events for the whole workforce – when Stan turned five, a tea was given for over 200 women and children from the village and the works.† Wreaths and banners were put up, a band played, and Stan received presents ranging from some fruit or a cake to toys and books.

Georgie found herself in sympathy with Alfred. Although her religious beliefs were less overt, her ideas of practical Christianity coloured much of her life. Unlike Burne-Jones, she had remained on close terms with Ruskin. In 1874 Rose La Touche, Ruskin’s former pupil, with whom he had been in love, had died after several years of nervous breakdowns and suffering most probably from anorexia nervosa. For the following two yean Ruskin was in an increasingly odd state of mind, which Whistler’s libel suit only exacerbated. When Ruskin returned from Italy in late 1877, it was clear he was heading for a major collapse. Georgie went to Brantwood, in the Lake District, to be with him in January 1878, taking Margaret with her. By February he was violent and completely divorced from reality: his diary shows his thoughts whirling around evil, Rose and sex. Georgie remained one of the faithful, only commenting yean later, ‘Now and then his brain gave way under the strain of thoughts and feelings that were beyond his power to express – I wonder more people don’t go distraught when they realize how much of life is a hand to hand fight.’13 Nearly forty yean after she had first met Mary Zambaco she saw life as travail. Then she had asked a friend to ‘Help me to rail at Fate a little, and then to bear it’.14 Now life was a fight to the death.

Things were, on the contrary, becoming easier for the Kiplings. Alice had stayed in England since she had removed Rudyard from Southsea, while Trix had been returned, happily, to Mrs Holloway for another year (another indication of how carefully Rudyard’s version of events must be treated) before being brought to London to attend Notting Hill High School. Rudyard was sent to Westward Ho! at the beginning of 1878. He had difficulty settling in at first. Although, unlike Phil at Marlborough, his background was not different from that of the other boys, * he missed the love and friendship he had become used to in the nine months since Alice had returned. Trix later remembered, ‘for the first month or so he wrote to us, twice or thrice daily (and my mother cried bitterly over the letters) that he could neither eat nor sleep … I remember my mother going in tears to my aunt, Lady Burne-Jones, who told her that her son had written exactly the same sort of letters but was now very happy.’16

Not precisely happy. By September 1878 Phil had more or less given up on school, and Georgie was looking for a tutor for him in the time before he could go up to Oxford. He was painting a bit, and to encourage him he was given the little studio over the dining room, which Burne-Jones had outgrown. He remained a worry to his parents. Withdrawn as a child, unhappy at school, as he progressed to maturity he came to be no more comfortable in his skin. By January 1879 he was in a state, and Burne-Jones was speaking ‘in a rather wild way’, saying ‘that [Phil] has given up all thought of Art’.17 By July Georgie was in despair. She spoke unguardedly of her lack of confidence in Phil’s abilities to Rosalind Howard, and then had to write asking her

to keep to yourself what I said to you about Phil on Saturday morning, for I feel as if I had been unjust to the boy to say as much as I did, and certainly that there is no need for me to feel while he is 17 as much as disappointment as I might if he were 21. He is a dear and good son to us, and I cannot bear the idea of labelling him with a fault. He has buckled to work with his tutor with a good grace and neither hope nor patience are exhausted in my heart.18

A shockingly harsh indictment of a child – and Phil was little more – implying a considerable burden of expectation. By twenty-one, clearly, it was expected that Phil would have found his way in life; if not, he would remain a ‘disappointment’. Margaret was judged by equally exacting standards; nor were her shortcomings kept in the family. When her daughter was eleven Georgie wrote to Charles Eliot Norton, their friend from Boston, that she had received a pair of shoes his daughter Sally had embroidered for her: ‘long would it be before Margaret could equal their art’. Sally also plays the violin, while ‘Margaret learns only that maid of all work the piano’. A letter from Margaret is forwarded to Sally ‘with all its probable imperfections of spelling, about which the address forbids me to affect no anxiety.’19* Any one of these comments would mean nothing, but the ceaseless barrage is daunting.

In the summer of 1878, before Phil left Oxford, Georgie had taken her second trip abroad, going with Margaret to France, where they met Ned and Phil, who had been spending some time in Paris and Normandy. For the first time the Kiplings were able to give their children similar treats. Lockwood had arrived in England in March. As well as having some well-earned leave, he was charged with responsibility for the Fine Arts of India Pavilion at the Exposition Universelle of 1878. † Lockwood and Rudyard spent five weeks together in Paris: a chance for Lockwood to acquaint himself with his son, just as Alice had done the previous summer. Lock-wood’s French had always been good – Trix remembered him reading aloud from books in French, translating as he went, with never a pause to think, or grope for words22 – and now he could show Rudyard around and then give him his first taste of freedom, allowing him to roam at will. After the Exposition, Lockwood returned to England, where he stayed until October 1879, before returning to Lahore via Venice – where he may have gone with the Poynters, who were certainly there that month.

This was a much-needed break for Agnes and Edward. In 1876 Poynter had decided that his responsibilities in central London – at University College, and at the South Kensington Museum – made the journey from Shepherd’s Bush every day too difficult. In addition, the job at South Kensington gave him a studio, and so a large house was no longer as necessary as it had been. As he had inherited his first rooms from Burne-Jones, so now he passed the lease of his house on to Walter Crane, who would benefit from the studio he had built in his garden. Crane had lived round the corner from them, and was close to Poynter, often coming to paint in the Beaumont Lodge studio when his own proved too small for the commissions he had on hand.* He now took it over permanently, and the Poynters moved briefly to a house in a small turning off Knightsbridge, Albert Terrace. By 1878 they had moved again, just down the road, to 28 Albert Gate. This had a much smaller garden than Beaumont Lodge, but it opened out at the back on to Hyde Park.

The size of the house had become less important, as had the garden, as in the autumn of 1878 Ambo went off to prep school. He and Stan were sent together. Agnes had spent so much time with Louie at Wilden that their sons were the closest of all the cousins. It was decided not to separate them, and to send them to a prep school in Slough – Hawtrey’s, which was a feeder school for Eton. Stan took the separation from his parents calmly. His father wrote, ‘You were a very good, brave boy this afternoon, and I was very pleased with your manly way. If you will be as good in your work as you are brave in your play while you are at school, you will indeed do well.’23

One of the great advantages of Hawtrey’s was that the boys were not far from London. Now that they had relocated to the centre of town, the Poynters could share in the family pastimes more easily, and Stan could join them. The Poynters’ drawing room was just the size for theatricals, and in January 1879 the large group of children – Burne-Joneses, Poynters, Morrises and various cousins and others – colonized Albert Gate. In their ‘in-house’ magazine, the Scribbler, they reported in their Drama section: ‘On the evening of the 17th instant a large and fashionable audience assembled at 28, Albert Gate, to witness a performance … we allude to the performance of Bluebeard, in twelve tableaux designed by and produced under the personal superintendence of, Messrs. E. J. Poynter and C. E. Hallé.’ Bluebeard was played by Ambo ‘in blue garment of eastern design – the turban absolutely gleaming with turquoise jewellery’. Miss M. Bell (Poynter’s niece) was Sister Anne, and Margaret was Fatima. There was a Stop Press: ‘We are sorry to hear that the performance of “Cymbeline” which was contemplated at the Grange Theatre, Fulham, has been abandoned; we trust only temporarily.’24

The mixture of popular and classic is revealing. The Poynters, the Baldwins and Georgie had a taste for opera and concerts -Edward and Agnes had a regular box at the opera and, in a longstanding arrangement, Georgie went with them. She also went to regular Monday concerts, taking Rosalind Howard’s tickets whenever she was out of London. The Poynters and Georgie went to Shakespeare as much as possible – taking the children to ‘suitable’ plays, with the Baldwins eager to join them whenever they were in town. Burne-Jones, on the other hand, found opera as dull as he had when he had first gone to Italy with Ruskin, and he was not much more interested in Shakespeare. He went instead with his bachelor friends to Gilbert and Sullivan, and sent George Howard an enthusiastic report: ‘I screamed and Armstrong screamed and Sanderson … I shall take Morris and Georgie there but I shan’t enjoy that – for they won’t laugh at all I know – indeed they say they won’t.’25 And indeed they didn’t. Morris reported glumly that he ‘thought [it] dreary stuff enough in spite of Burne-Jones’.26 It gradually became accepted that it was better to keep their outings separate than suffer each other‘s tastes.

*

In 1880 Alice prepared to return to Lahore. Trix was brought back from Southsea to attend her new London school, and lodged with some ‘ladies’ nearby – there were apparently still too many ‘complications’ to ask Georgie to look after her, even though Trix and Margaret were to be together at school. This may have been because the Grange was in a state of upheaval – a semi-permanent situation. The architect W. A. S. Benson was building a new studio across the end of the garden, and hot-pipes were being laid, although only to heat the studio.* Nor was Rudyard to stay at the Grange with his ‘beloved Aunt’ when he was not at Westward Ho! Early in his schooldays he spent part of his holidays with Fred’s family. This was clearly enjoyed by Rudyard as well as by the Macdonalds. One gets a glimpse of the devilry that Mrs Holloway had been at such oppressive pains to eliminate. His cousin remembered when, after being scolded for his grubby appearance, ‘my mother gave him sixpence to go to the hairdressers … When he came back his head was shaved and my mother said to him, “Ruddy, what have you done?” “I am sick of all the fuss about a parting … Now there isn’t going to be one.”’27

The Burne-Joneses were fully occupied, and they didn’t seem to have room for a nephew and niece. Georgie, said Ned half admiringly, half despairingly, ‘is tremendous and stirs up the house into a froth every morning’,28 so that it smelt of ‘Soap and washing so that I dread going into my studio for fear Rachel [the housemaid] should have washed my pictures’.29 Although Burne-Jones claimed never to go anywhere, and never to see anyone (‘it is very dull’),30 a list of Sunday callers taken at random from one of his letters shows Morris arriving for breakfast as usual, followed by Walter Crane and the Slade Professor at Cambridge, Sidney Colvin, in the morning; four guests for lunch; then ‘callers’, unnamed, in the afternoon.31 In addition, in 1879 Burne-Jones was invited to Hawarden, Gladstone’s house in Flintshire. He claimed not to have wanted to go; and to have hated it while he was there (‘from the dawn when a bore of a man comes and empties my pockets and laughs at my underclothing and carries them away from me, and brings me unnecessary tea, right on till heavy midnight …’).32 But he went, and he made sure everybody knew where he’d been.

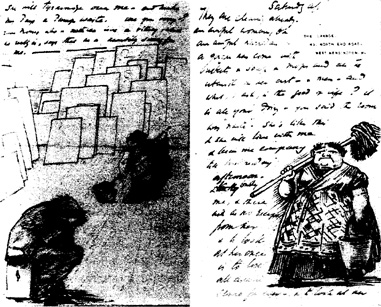

A letter from Burne-Jones with caricatures of himself in his studio with the cleaning lady

The Grange was not Georgie’s only concern. The Burne-Joneses had become accustomed to going down to the south coast whenever they felt they needed a break, or a change. In 1880 Georgie found a cottage in Rottingdean, then a tiny village outside Brighton, which they quickly bought. It was small, without being either the ‘mean cheap contemptible’ house Burne-Jones described to his friends or the ‘mansion’ Rossetti snidely referred to.33 Prospect House (later to be renamed North End House, in honour of the Grange, on North End Road) was pleasantly situated, away from the day trippers who besieged Brighton, while it was near enough Brighton station to make running down for a weekend feasible.* There was a cottage next door that could be rented when the Baldwins came to visit, which they began to do fairly regularly. Money was now plentiful for the Baldwins, and they were spending several months a year in London at a small hotel. Alfred was beginning to have commercial reasons to be there, and Louie was, as always, in search of health. Doctors were to be found in London; invigorating sea air in Rottingdean.

Georgie was probably pleased to have Louie nearby more often. For the last decade she had had one great woman-friend in George Eliot. They had first met soon after the Burne-Joneses had moved into the Grange, and during the Mary Zambaco crisis Georgie had become closer to both George Eliot and G. H. Lewes, spending time with them at Whitby in the summers. Georgie was ‘Mignon’ and ‘dear little Epigram’ to Eliot’s ‘Lady Theory’ and Lewes’s ‘the good Knight Sir Practice’. By the late 1870s Georgie was going to Eliot every Friday, when no other visitors were expected, and Lewes was suggesting sharing the Christmas holidays. When Eliot and Lewes went to Wiltshire on holiday, they called in as a matter of course at Marlborough to see Phil; Georgie and Eliot shared similar tastes in books and music, and for more than a decade had gone to concerts and lectures together. When Lewes died in 1878, Georgie, defying the convention that women did not go to the burial of even their closest family, had attended his funeral. Then, suddenly, in 1880, she received a note from Eliot telling her she had eloped with ‘Johnny’ Cross, twenty years her junior. Eliot knew what a shock it would be, and wrote:

If it alters your conception of me so thoroughly that you must henceforth regard me as a new person, a stranger to you, I shall not take it hardly, for I myself a little while ago should have said this thing could not be … I can only ask you and your husband to imagine and interpret according to your deep experience and loving kindness.35

Georgie’s response initially seems as spontaneously open as Eliot could have hoped for:

I have been away with the exception of one clear day … when I returned and found your letter … and I cannot sleep till it is answered. Dear friend, I love you – let that be all – I love you, and you are you to me ‘in all changes’ – from the first hour I knew you until now you have never turned but one face upon me, and I do not expect to lose you now. I am the old, loving Georgie.

It becomes clear, however, from her next letter to Eliot, six weeks later, that she had not sent this letter – nor any other:

Dear Friend

You will see by the enclosed [the letter cited above] that I answered your letter at once and that I was grateful for it – but when my answer was written I put it aside, hoping to find more and brighter words to send. Forgive it if they have not come yet, and let me send those first ones…

Give me time – this was the one ‘change’ I was unprepared for – but that is my own fault – I have no right to impute to my friends what they do not claim. Forgive what would be an unforgivable liberty of speech if you had not said anything on the subject to me or if you had not also looked closely into my life.36

As Georgie drily noted to Rosalind Howard, ‘Mrs. Lewes’s marriage has been a great shock to me – but I am obliged to fall back on the undoubted fact that she had a perfect right to do what she thinks fit in the matter.’37 Georgie never had a chance to resolve this sense of betrayal: by December Eliot was dead, and Georgie’s final comment on her great friend was a sad little ‘I loved her vy much – more than I loved her work – and I miss her out of the world sadly.’38 She should have remembered Eliot’s response when she had talked of her reticence: ‘Ah! Say I love you to those you love. The eternal silence is long enough to be silent in.’39

Added to this loss was an increasing worry about Louie. Certainly she had been unwell for most of the last dozen years – often in a bath chair, unable to get downstairs for breakfast for years at a time. Yet within these very confined parameters she had managed to lead a relatively normal life. (When one of Alfred’s brothers died in 1881, at the young age of fifty-five, leaving behind several children, Alfred and Louie took in the dead brother’s son, Harold, who was almost the same age as Stan.) In October 1881 Louie’s illnesses worsened. Stan had left the month before to start his first term at Harrow. Almost immediately afterwards he promptly came down with scarlet fever, and was forced to remain at school because his mother was lying flat in a darkened room, being fed by a tube. Agnes spent over two months at Wilden, looking after her sister with Edie and sending bulletins back to London. Louie had been living ‘at too high pressure’, she had ‘exhausted’ her brain. Georgie reported ‘no distinct disease, but prostration so agonising that for a day or two they almost despaired of reviving her’.40* By December things were getting worse – Louie now needed a trained nurse (or Alfred, Edie and Agnes did); Georgie was summoned; Stan returned from school. There was little change, and gradually they disbanded. In January, Louie, with the nurse, followed her sisters to London, where she stayed, neither better nor worse, for another three months.

Agnes’s presence for so long in Wilden was a kindness. In addition to getting Ambo ready for Eton, where he went in September, she was, much to her (and everyone else’s) embarrassment, pregnant again. In January 1882, nearly fifteen years after the birth of Ambo, she had another son, Hugh. To add to the general air of farce, she went into labour at a dinner party, and had to be carried home. Alice, in India, took the whole thing personally. She wrote to Editha Plowden:

You will be amused to hear that up to this time your letter is the only one that has brought one tiding of my sister Agnes. But for your little PS I should even yet know nothing but what I have seen in the papers and from a para, in the World … I won’t pretend that I am not very much amazed by having had no letter from any one of my sisters. They treat me in this way and are yet surprised when I say that out here I feel cut off from them all! I shall not mention the matter in any home letter until I hear from some one …,42

It is not clear if Alice had not heard about the birth in what she considered good time, or if she had not been aware that Agnes was pregnant. The latter seems incredible, but it may be possible. Before she had had time to post the letter, however, she had heard from both Rudyard and Georgie:

Last night brought a letter from Mrs Burne-Jones from which I am glad to learn that badly as poor Aggie managed her affairs they might have been worse and that she was going on all right. Ruddy writes very funny about it. He says he saw the news in the World and adds ‘Est-ce que mes tantes sont done folles? … At first I had a confused idea that I was an uncle or a grand-papa, but on mature reflection I find that I am only another cousin … Can you imagine Uncle Edward’s face?’ All this shows a very just appreciation of the situation.

If she knew of the pregnancy and had simply not had news of the birth of Hugh, then the postal system would have been the main cause. The mails to India left England every Friday; letters then took eighteen days to reach Bombay, and at least a week after that to reach Lahore (it took a person three or four days by train). From the fact that two letters arrived while this one was being written, Georgie had written to let Alice know within a fortnight of the birth. Alice’s letter may be general grumbling, or it may have a more specific cause. Alice was worried about Trix. Rudyard, said his mother, reported that

a sensitive plant is pachydermatous by comparison to her. She seems to have got – who knows how or where – some morbid religious notions and is tormenting herself with the fear that we shall be disappointed in her in some way … If you would see her sometimes and try to cheer her … My sisters seem too much occupied to take much notice of her – she had not up to last mail seen Mrs. Poynter’s baby – and I know she is feeling lonely in a crowd.43

In addition, she and Lockwood were now concerned about Rudyard’s future. He was approaching sixteen, and had no ideas for a career. Although he ‘fairly pelt[ed]’ her with poems and letters, ‘I always open his letters with a feeling of trepidation, though I don’t know why.’44 One reason may have been guilt. Stan was at Harrow, and was planning for Cambridge; Phil had been at Oxford (although he had lasted only a year and, like his Uncle Harry, had gone down without a degree, to his parents’ distress); Ambo was planning to follow his grandfather’s path and become an architect; Georgie was even talking about university for Margaret. It must have been hard that Alice and Lockwood, like their parents before them, knew that economics meant they could not hope to send their children to university. But they couldn’t – despite the fact that Alice had started writing ‘Simla gossip letters’ for the Bombay Gazette and the Civil and Military Gazette around this time. These would only help pay for their time in the hills to avoid the hot weather – there wasn’t nearly enough for anything else.

Alice and Lockwood took their anxieties once more to Crom Price. Rudyard had an ‘easy-going general interest… in all things’, and ‘journalism seems to be specially invented for such desultory souls’.45 The idea, once planted, grew steadily. Not only had Alice and Lockwood an ‘in’ with various papers in India, a job there would also enable them to have Rudyard living with them again. They even began to contemplate Trix’s return:

We should be together as a family square for a few years at any rate … John would grow younger with his son and daughter by him – a process he sorely needs for he is getting so dreadfully absorbed in things that he is rarely now the conversational companion he used. For me the companionship of these bright young creatures would be new life – I have never been cheerful except by excited spurts since I came out last and I often wonder if this dull depressed woman can be the same she was in England … if there were no other reasons for it there’s the pecuniary one – that is strong enough. Our income which would be a good one if we were all here under one roof – does not bear division and sub-division … we are really feeling a pinch at present.46

Lockwood had been working flat out preparing for the Punjab Exhibition, designed to display to the rest of India the arts of the north. Alice, as always, worked closely with him – she had charge of the textile section – and they were both exhausted.

It was hard for them to hear news from home: Poynter, from his position at the South Kensington Museum, was offering Queen Victoria advice on portraitists; Burne-Jones had received an honorary degree at Oxford, which put Lockwood’s University of Bombay fellowship in the shade. Even acknowledging this, it is clear that Alice’s sharpness was now turning into outright harshness. She made no allowances for anyone. One did not have to offend her directly to be on the receiving end of her strictures:

Mrs. Molloy (née Miss Townsend) was down … looking as she always did, like a good little housemaid. Our new young ladies are rather a failure. Mrs. Black’s daughter is a dumpy girl – who I believe speaks some when spoken to and we thought her rather plain till Mrs. Parry Lambert’s daughter came, and by her transcending ugliness made Miss Black seem almost beautiful. You remember Major Lambert who is no beauty? She is like him – but much plainer. Her eyes are slits and her mouth a gash, the upper lip doesn’t cover the teeth. The nose turns up and the cheeks are large and shapeless – she is short, dumpy and has large hands – altogether she might be an Irish maid of all work in a lodging house …47

Despite this, Lockwood retained touching faith in his wife’s social skills. When Editha was in trouble he ‘hope[d] you told Mrs. Kipling something of your affairs. Besides sympathy, you would get the brightest sense put in the most convenient form for reference.’48

Two years before, in 1880, Fred had gone to the General Conference of Methodist Episcopalian Churches in America. There he had visited Harry and his wife, and to his regret discovered that as ‘we had seen nothing of one another during a long period in which each of us had changed and developed … All the memories we had in common were those belonging to our earliest days.’49 That is, they had nothing in common, and not much interest in catching up. None of the Kiplings would be returning to England – ‘home’ – for many years, but perhaps the same situation was what Alice feared for her children – and herself.